Abstract

Quercetin plays an important role in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury (IRI). However, the underlying mechanism for the protective effect of quercetin is largely unclear. In this study, we explored the protected effects of quercetin against myocardial IRI and its molecular mechanisms. Quercetin, GW9962 (PPARγ antagonist) or PPARγ-siRNA was administered alone or in combination prior to myocardial IRI in mice or to hypoxia and reoxygenation (H/R) treatment in H9C2 cells. Infarct size was evaluated by TTC staining after reperfusion. Myocardial injury was assessed by the serum levels of AST, CK-MB, cardiac troponin T (cTnT) and LDH. Cardiac function was measured by echocardiography. Oxidative stress injury was evaluated by analyses of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), MDA, SOD and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-PX) levels and by reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection. Myocardium apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL staining, cleaved caspase-3 and Annexin V/PI detection. Moreover, activation of the NF-κB pathway was reflected by phosphorylation of IκB (p-IκB) and nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65. We reported that pretreatment of quercetin significantly improved cardiac function, diminished myocardial injury and reduced the infarct size. Myocardium oxidative damage and apoptosis were remarkably improved by quercetin treatment in vivo and in vitro. Quercetin also suppressed the activation of the NF-κB pathway induced by myocardial IRI. GW9662 or PPARγ knockdown partially attenuated these cardioprotective effects of quercetin during myocardial IRI. In conclusion, our findings suggest that quercetin ameliorated IRI-induced heart damage via PPARγ activation and the underlying mechanism might involve the inhibition of NF-κB pathway by PPARγ activation.

Keywords: Quercetin, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, myocardium, ischemia-reperfusion injury, NF-κB pathway

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a common cardiovascular emergency [1]. With the development of economy and society, the incidence of AMI showed an upward trend year by year. World Health Organization (WHO) has predicted that by 2020, AMI would become one of the major causes of human death [2]. At present, percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass surgery are two major therapeutic approaches to treat myocardiac ischemia. However, fast restoration of the blood supply can result in additional myocardial injury and complications, such as myocardial IRI, and then causing multiple pathological changes including acute inflammatory cascade, metabolic disorders and cell death, and these changes eventually lead to cardiac dysfunction and ventricular remodeling [3]. Mechanisms underlying myocardial IRI involve calcium overload, oxidative stress, release of cytokines and neutrophil infiltration [4]. Although drug clinical trials on myocardial IRI have yielded encouraging results, the actual effect of clinical treatment is not satisfactory [5]. Therefore, development of new cardioprotective drugs against myocardial IRI remains the research hotspot.

Quercetin (3,5,7,3’,4’-pentahydroxyflavone) is a polyphenolic compound presents in various vegetables and fruits such as onion and apple. It has various biological functions including anti-inflammatory, anti-coagulation, and oxygen radical-scavenging activity [6,7]. Application of quercetin before ischemia or during reperfusion has been found to protect myocardium from IRI in an acute myocardial IRI rat model [8]. However, mechanisms underlying this protective effect remain unclear.

Several reports have revealed that quercetin could up-regulate PPARγ expression to exert biological functions [9]. PPARγ is a ligand-activated nuclear transcription factor and participates in a variety of physiological and pathological processes [10]. As early as 1996, Shimabukuro found that PPARγ agonist troglitazone could not only reduce the insulin resistance, but also protect against post-ischemic cardiac dysfunction and ultrastructural damage induced by chronic diabetes [11]. In addition, studies have shown that PPARγ activation could suppress inflammation in immune-competent organs suffered from IRI and thus alleviate ischemic pathological damage [12]. However, the molecular mechanisms by which PPARγ activation protects against myocardial IRI are largely unknown.

The NF-κB pathway plays an important role in IRI in almost all of organs [13,14]. It is an important redox-sensitive transcription factor, which regulates the expression of many inflammatory genes [15]. Inactivation of the NF-κB pathway in cardiomyocytes has cardioprotective effects against ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial oxidative stress injury, cell death and other injuries [16-18]. In addition, PPARγ could negatively regulate NF-κB pathway in various pathological settings such as inflammation-associated skeletal muscle abnormalities, liver carcinoma and vascular diseases [19-22].

Based on these reported findings, we hypothesized that the protective effects of quercetin against myocardial IRI would involve PPARγ and the NF-κB pathway.

The present experiments demonstrate that the quercetin has ability to increase PPARγ expression; quercetin pre-treatment alleviates myocardial damage and ventricular dysfunction, prevents oxidative stress injury and myocardium apoptosis, suppresses NF-κB activation caused by IRI. These cardioprotective effects of quercetin were partially blunted by PPARγ blockade.

These findings would suggest a new mechanism that quercetin application inhibits myocardial IRI and NF-κB pathway via PPARγ.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Quercetin (C15H10O7; formula weight =302.24, purity ≥95%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). GW9662 was purchased from MedChemExpress (Princeton, NJ, USA). Serum AST and LDH assay kits were purchased from Biosino Bio-Technology and Science (Beijing, China). Serum CK-MB assay kit were obtained from Uscn Life Science (Wuhan, China). Tissue SOD, GSH-PX activity assay kits and MDA content assay kit was purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Serum cTnT enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit were purchased from Shanghai Westang Bio-tech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). Dihydroethidium (DHE) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Anti-PPARγ and GAPDH antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Anti-Caspase-3, iNOS, NF-κB p65, p-IκBα antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). The terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kit was purchased from Roche Lifescience (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Annexin V-FITC/PI kit was purchased from ebioscience (San Diego, CA, USA).

Animals

Male C57/BL6-mice (10-12 weeks old; weight, 20-22 g) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (Shanghai, China). Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) laboratory under optimum conditions (25 ± 2°C, 55% humidity, and a 12 h light/dark cycle) and fed a standard laboratory diet and water. All animals were allowed to acclimatize in the animal cages for 1 week prior to use. All the animal procedures were performed to conform the NIH guidelines (Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals) and Use Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

In vivo IRI in mouse myocardium

Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation. A rodent ventilator (model 683, Harvard Apparatus, Inc. Holliston, MA, USA) was used with 65% oxygen during the surgical procedure. The animals were kept warm using heat lamps and heating pads. Rectal temperature was monitored and maintained between 36.5 and 37.5°C. The chest was opened by a horizontal incision through the muscle between the ribs at the third intercostal space. Ischemia was achieved by ligating the anterior descending branch of the left coronary artery (LAD) using an 8-0 nylon suture, with a silicon tubing (1 mm outside diameter) placed on top of the LAD 2 mm below the border between the left atrium and left ventricular (LV). Regional ischemia was confirmed by ECG changes (ST elevation). After occlusion for 30 min, the silicon tubing was removed to achieve reperfusion for 24 h.

Experimental protocols in vivo

The mice were randomized into five groups as follows: i) Sham-operated group (Sham; n=6): Mice were given dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) by oral gavage and intraperitoneally injection for 10 days and then sacrificed on the 11th day. The animals were subjected to the entire surgical procedure and thread was passed beneath the LAD, but was not ligated. ii) Myocardial IRI group (IRI; n=6): In this group, mice were given DMSO by oral gavage and intraperitoneally injection for 10 days, thereafter, on the 11th day, the experimental animals were subjected to a 30 minutes LAD ligation followed by a 24 h reperfusion induced myocardial IRI. iii) Myocardial IRI plus quercetin group (IRI+quercetin; n=6): quercetin (250 mg/kg/day) [23] was dissolved in DMSO and was administered by oral gavage and DMSO intraperitoneally injection for 10 days, on the 11th day, the mice were subjected to a protocol of a 30 minutes LAD coronary artery ligation and a 24 hours reperfusion. iv) Myocardial IRI plus quercetin plus GW9662 group (IRI+quercetin+GW9662; n=6): In this group, GW9662 (1 mg/kg/day) [24] was dissolved in DMSO and mice were treated intraperitoneally with it 15 min prior to the quercetin (250 mg/kg/day) for 10 days. On the 11th day, the mice were subjected to a 30 minutes LAD ligation followed by 24 hours reperfusion. v) Myocardial IRI plus GW9662 group (IRI+GW9662; n=6), DMSO administered by oral gavage and GW9662 (1 mg/kg/day) was injected intraperitoneally to animals for 10 days. On the 11th day, the mice were subjected to a protocol of a 30 minutes LAD ligation and a 24 hours reperfusion.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) detection of PPARγ

Heart sections were exposed to 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min to destroy endogenous peroxidases activity and then blocked with bovine serum albumin for 30 min. Sections were subsequently incubated in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-mouse PPARγ antibody (1:400 dilution) diluted in a solution of 0.3% Triton X-100. Sections were then incubated with anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing in PBS, immunoreactivity was detected with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Finally, the sections were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, mounted in xylene and coverslipped. The results were expressed as the number of positive cells per mm2 tissue section counted in five randomly selected visual fields under high magnification (400×).

Measurement of infarct size

After IRI, the animals were re-anesthetized and intubated, and the chest was opened again. After the heart at the diastolic phase was arrested by KCl injection, the ascending aorta was cannulated and perfused with normal saline to wash out the blood. Then the LAD was occluded on the same suture which had been left at the site of the ligation. To demarcate the ischemic area at risk (AAR), Evans blue dye (1%) was perfused into the aorta and coronary arteries. Then hearts were excised, and the LV was sliced into 1-mm-thick cross-sections. The heart sections were then incubated with 1% TTC solution at 37°C for 10 minand then placed in 4% formaldehyde solution overnight. The size of infarct area (INF) (pale white), the AAR (brick red), and non-ischemic area (blue) from both sides of each section were measured by two blinded observers using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems, Inc.), and the values obtained were averaged. The percentage of INF and AAR of each section was multiplied by the weight of the section and then added up. AAR/LV and INF/AAR were expressed as a percentage.

Myocardial damage assessment

The myocardial damage was evaluated by measuring the level of myocardial-specific markers, including AST, CK-MB, cTnT and LDH. After reperfusion, blood was taken from the carotid artery and was placed at room temperature for 30 min. Then, the serum was collected by centrifugation and placed at -70°C for preservation. These levels were measured using commercial kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed using the Vevo 770 high-resolution echocardio-graphic system (Visual Sonics Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada) at 24 h after myocardial IRI as previously described [25]. Six animals were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation and placed in supine position. The chest was shaved, and the parasternal short- and long-axis views were used to obtain two-dimensional and M-mode images by an echocardiogram. Ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) were calculated from digital images using Vevo 770 software. At least 10 independent cardiac cycles per each experiment were obtained. Cardiac output was normalized with the animals’ weights to obtain cardiac indices.

Detection of MDA, SOD and GSH-PX content

After reperfusion, myocardial tissue was homogenized in ice-cold PBS to make a 10% homogenate. MDA, SOD and GSH-PX in the supernatant were measured by using commercially available kits. The assay results were normalized to the protein concentration in each sample, and expressed as U/mg protein or nmol/mg protein.

TUNEL assay

Mice were euthanized, and paraffin sections were prepared as described above. TUNEL assays were performed using the TUNEL assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction. In order to test the apoptotic rate, five visual fields were chosen randomly from each section and positive brown cells and total cells were counted by MIAS4.0 (Medical Image Analysis System, Bingyang Keji Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) and the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells/total cells was calculated for statistical analysis.

Western blot analysis

Protein extracts were prepared according to the method described in the protein extract kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). Protein concentrations were measured using the BCA Protein assay kit (Piece Biotechnology, Rockford, Ala, USA) and size separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide (SDS) gel electrophoresis. Proteins were blotted to nitrocellulose membrane. Blots were incubated with antibodies against PPARγ, iNOS, cleaved-caspase-3, p-IκBα and GAPDH. Goat anti-rabbit IgG were added and the blots were developed with ECL plus kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Cell culture

Myocardial H9C2 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and routinely cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with D-glucose at 4.5 g/L, 10% FBS, in an incubator with 5% CO2, at 37°C. The medium was changed every 2 days, when confluence was reached, the cells were subcultured by detaching with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma) and re-seeding into new plates at a ratio of 1:3, then incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS, cells were kept at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator.

RNA interference (RNAi)

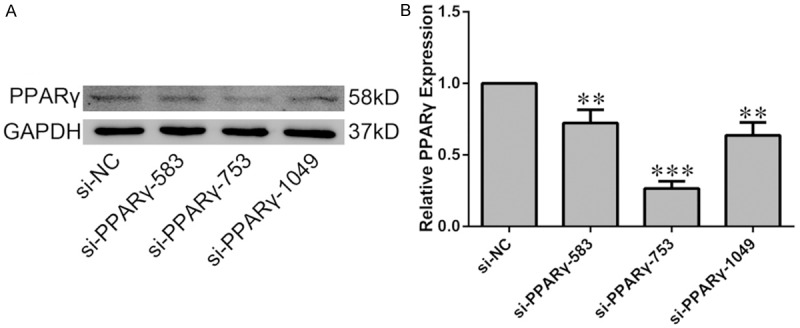

For the RNAi experiment, no-specific (negative control, NC) and PPARγ-specfic siRNA oligonucleotide were designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China), the siRNA sequences were listed in Table 1. H9C2 cells in six-well plates were transfected with the NC or PPARγ-siRNA oligonucleotide (final concentration was 100 nmol/L) with Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The most efficient RNAi sequence was the PPARγ-rat-753, the interference efficiency on PPARγ expression was about 70% (Figure 5). Thus, we chose this sequence (PPARγ-rat-753) to perform RNAi experiment.

Table 1.

Sequences of siRNA

| Genes | Sequences |

|---|---|

| Negative control (siNC) | Sense: 5’-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3’ |

| Antisense: 5’-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3’ | |

| siPPARγ-rat-583 | Sense: 5’-CCAUCCGAUUGAAGCUUAUTT-3’ |

| Antisense: 5’-AUAAGCUUCAAUCGGAUGGTT-3’ | |

| siPPARγ-rat-753 | Sense: 5’-GCGGAGAUCUCCAGUGAUATT-3’ |

| Antisense: 5’-UAUCACUGGAGAUCUCCGCTT-3’ | |

| siPPARγ-rat-1049 | Sense: 5’-GCAAGAGAUCACAGAGUAUTT-3’ |

| Antisense: 5’-AUACUCUGUGAUCUCUUGCTT-3’ |

Figure 5.

Efficiency of PPARγ knockdown in H9C2 cells. H9C2 cells were transiently transfected with siRNA targeting PPARγ or non-specific siRNA (si-NC). A. The knockdown efficiency was evaluated by western blot analysis. B. Quantification of the densitometry of western blot bands. Data shown represent mean ± SD. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs NC-siRNA group. The experiment was repeated three times.

Hypoxia and reoxygenation (H/R)

H9C2 cell line was cultured in an airtight incubation tank for 6 h with a <1% oxygen concentration and followed by 0.5 hour of reoxygenation. This in vitro treatment is the simulation of myocardial IRI in vivo.

Experimental protocols in vitro

The cultured H9C2 cells were randomly divided into different groups similar that described in the in vivo experiment. H9C2 cells were pretreated with 40 μM quercetin for 24 h [26], combined or not combined with PPARγ-siRNA and then subjected to H/R as described above. The groups were as follows: i) Sham treatment group (Sham): H9C2 treated with DMSO and cultured in normoxic condition; ii) H/R group (H/R+NC-siRNA): H9C2 transfected NC-siRNA and pretreated with DMSO and then suffered H/R; iii) H/R plus quercetin group (H/R+quercetin+NC-siRNA): H9C2 transfected NC-siRNA and pretreated with quercetin and suffered H/R; iv) H/R plus quercetin plus PPARγ-siRNA group (H/R+quercetin+PPARγ-siRNA): H9C2 transfected PPARγ-siRNA and pretreated with quercetin and suffered H/R; v) H/R plus PPARγ-siRNA group (H/R+PPARγ-siRNA): H9C2 transfected PPARγ-siRNA and pretreated with DMSO and suffered H/R.

Detecting the ROS generation

The generation of myocardial ROS was assessed using DHE. Briefly, after cell culture medium was discarded, cells were incubated with 100 μmol/L DHE for 30 min at 37°C, then cells were washed twice with PBS and viewed under the fluorescence microscope (magnification ×400; Nikon, Japan) under identical exposure conditions, the optical densities of the staining were measured in randomly selected images (five visual fields per group).

Detection of apoptotic cells by flow cytometry

The apoptosis of cardiomyocyte in vitro was measured by flow cytometry using an Annexin V-FITC/PI kit. Briefly, H9C2 cells (1×106) were washed twice with cold PBS and labelled with FITC-conjugated Annexin-V in the dark for 10 min at room temperature. Five minutes after propidium iodide (PI) solution was added, the percentages of dead cells and cells undergoing apoptosis were evaluated by flow cytometry (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence analysis of NF-κB pathway activation

After treatment, H9C2 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 5 min. After fixation and permeabilization, cells were washed twice with PBS containing 1% BSA and then incubated with primary antibody for NF-κB p65 overnight at 4°C, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermofisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Then the cells were counterstained with DAPI (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). The stained cells were viewed under the fluorescence microscope (magnification ×400; Nikon, Japan).

Statistical analysis

The results were presented as the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were performed using SPSS 19.0. Parametrical data were compared using Student’s t test. One-way ANOVA analysis was used to determine the difference between independent groups. P<0.05 was denoted as statistically significant.

Results

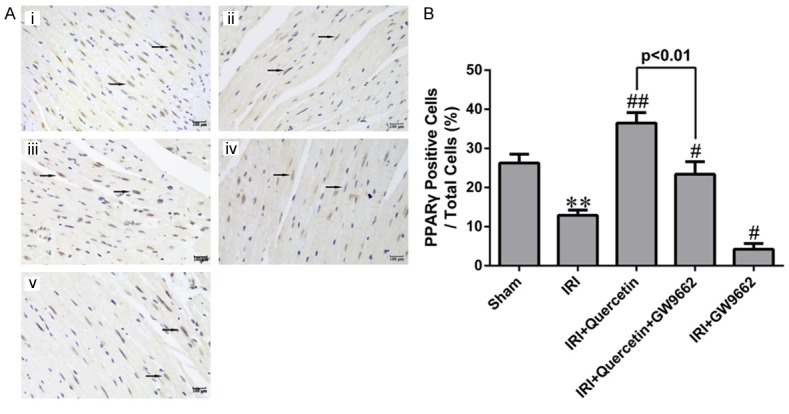

Quercetin up-regulated the expression of PPARγ in IRI hearts

To investigate whether PPARγ is involved in the protective effect of quercetin against myocardial IRI, we measured the expression level of PPARγ in myocardium of myocardial IRI mice with or without quercetin treatment (Figure 1). PPARγ expression level in the myocardial IRI group was significantly decreased compared with that of the Sham group. Moreover, quercetin treatment reversed the reduction of PPARγ expression level in the IRI group.

Figure 1.

The expression of PPARγ in myocardial IRI mice in vivo. A. Representative images of IHC analysis of PPARγ expression in mouse myocardial sections of different groups. (i) Sham-operated mice treated with vehicles (Sham). (ii) Myocardial IRI mice treated with vehicles (IRI). (iii) Myocardial IRI mice treated with quercetin (IRI+Quercetin). (iv) Myocardial IRI mice treated with GW9662 and quercetin (IRI+Quercetin+GW9662). (v) Myocardial IRI mice treated with GW9662 (IRI+GW9662). PPARγ-positive nuclei are indicated by arrows (magnification 400×). B. Quantification of PPARγ-positive cells (black arrows in photograph A) in different groups (five fields for each specimen). Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). **P<0.01 vs Sham group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs IRI group. All experiments were repeated six times.

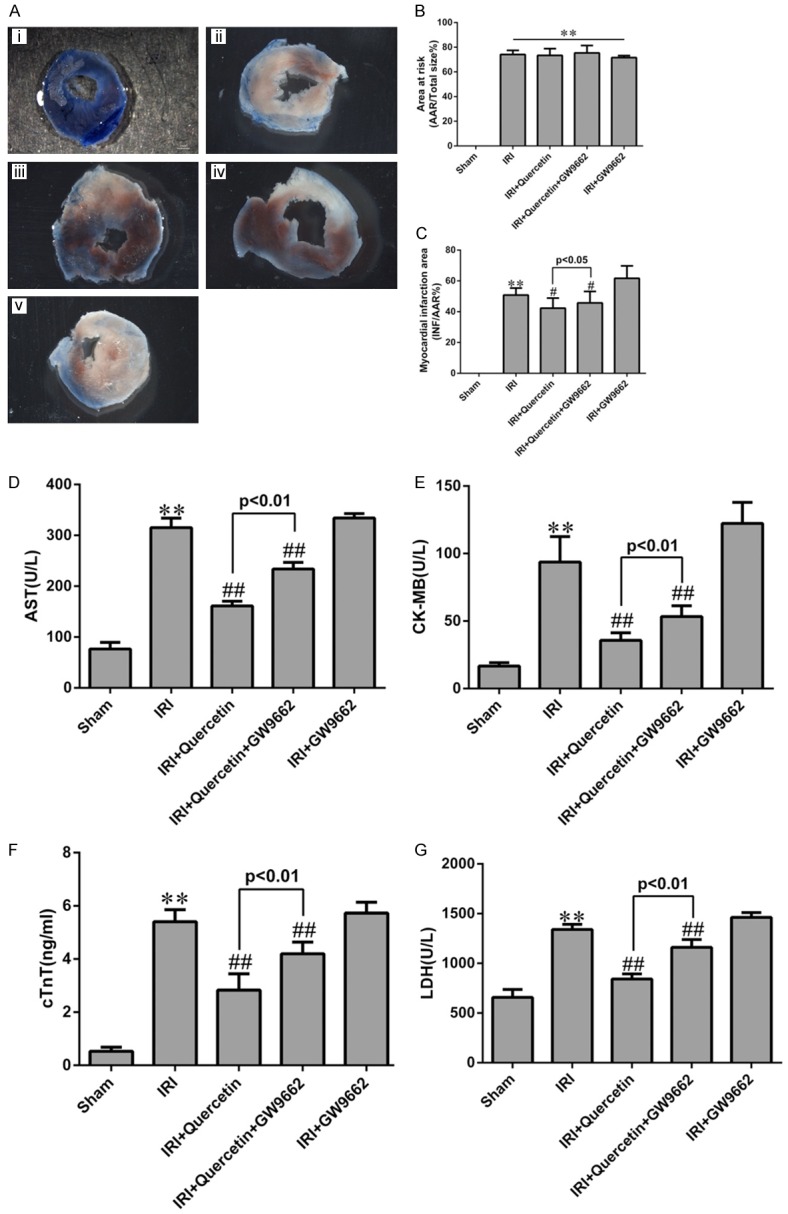

Quercetin reduced infarct size and attenuated myocardial damage in myocardial IRI mice via PPARγ activation

To further investigate whether PPARγ mediates the protective effect of quercetin in myocardial IRI mice, we examined the effect of a kind of PPARγ inhibitor GW9662 in quercetin-treated mice. GW9662 treatment indeed attenuated both the basal and quercetin-induced PPARγ expression (Figure 1), validating its inhibitory effect on PPARγ. We next evaluated myocardial infarction through measuring the percentages of AAR/LV and INF/AAR as previously described [27]. Evans Blue/TTC staining of heart sections revealed that AAR/LV (%) was similar among all IRI groups regardless of quercetin and/or GW9662 treatment (Figure 2B). Quercetin (250 mg/kg) treatment for 10 days significantly decreased the percentage of INF/AAR in myocardial IRI mice (30 min ischemia followed by 24 h reperfusion) (Figure 2C). Interestingly, GW9662 treatment partially reversed the decrease in INF/AAR induced by quercetin, suggesting that PPARγ activation is required for the cardioprotective effect of quercetin. IRI-induced myocardial damage was further evaluated by measuring the release of several markers, including AST, CK-MB, cTnT and LDH, into the serum. Consistent with the findings for the myocardial infarction analysis, quercetin treatment decreased the serum levels of these markers, and such protective effect was also abolished by GW9662 treatment (Figure 2D-G).

Figure 2.

Effects of quercetin and PPARγ inhibitor on myocardial infarct size and myocardial enzyme leakage. A. Myocardial infarct size was determined by TTC staining. Representative TTC-stained myocardial sections were shown. Blue-stained areas indicate normal tissue, red-stained areas indicate AAR and unstained pale areas indicate INF. AAR and INF sizes were subsequently measured. (i) Sham-operated mice treated with vehicles (Sham). (ii) Myocardial IRI mice treated with vehicles (IRI). (iii) Myocardial IRI mice treated with quercetin (IRI+Quercetin). (iv) Myocardial IRI mice treated with GW9662 and quercetin (IRI+Quercetin+GW9662). (v) Myocardial IRI mice treated with GW9662 (IRI+GW9662). B. The percentage of AAR to the total left ventricular area 24 h post IRI in the indicated groups. C. The percentage of INF area to AAR 24 h post IRI in the indicated groups. D-G. Total AST, CK-MB, cTnT and LDH levels in arterial blood (n=6). **P<0.01 vs Sham group, #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs IRI group. The experiment was repeated six times.

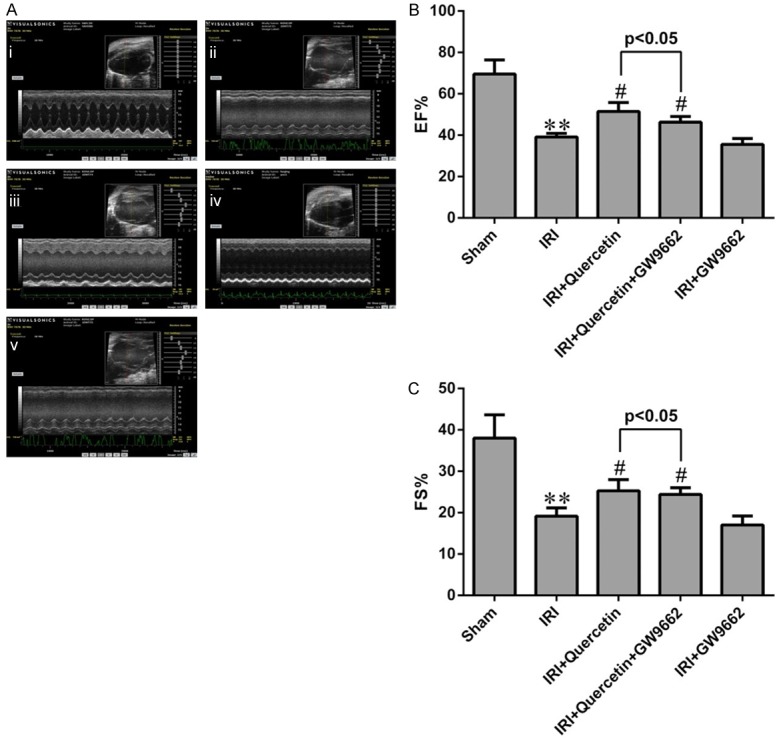

Quercetin restored LV function after myocardial IRI in mice via activation of PPARγ

At 24 h post-IRI, the mice exhibited a pronounced decline in LV function, reflected by an attenuation of LV wall motion and reduction of EF and FS. The LV function was significantly improved by quercetin treatment in these IRI mice (Figure 3A-C). Similarly, these protective effects of quercetin on LV function in myocardial IRI were abolished by GW9662 treatment (Figure 3A-C).

Figure 3.

Effects of quercetin and PPARγ inhibitor on cardiac function after IRI in vivo. A. Representative M-mode echocardiography of mice 24 h after myocardial IRI. (i) Sham-operated mice treated with vehicles (Sham). (ii) Myocardial IRI mice treated with vehicles (IRI). (iii) Myocardial IRI mice treated with quercetin (IRI+Quercetin). (iv) Myocardial IRI mice treated with GW9662 and quercetin (IRI+Quercetin+GW9662). (v) Myocardial IRI mice treated with GW9662 (IRI+GW9662). B, C. The percentages of EF and FS were measured 24 h post IRI in different groups. **P<0.01 compared with the Sham group. #P<0.05 compared with the IRI group. All experiments were repeated six times.

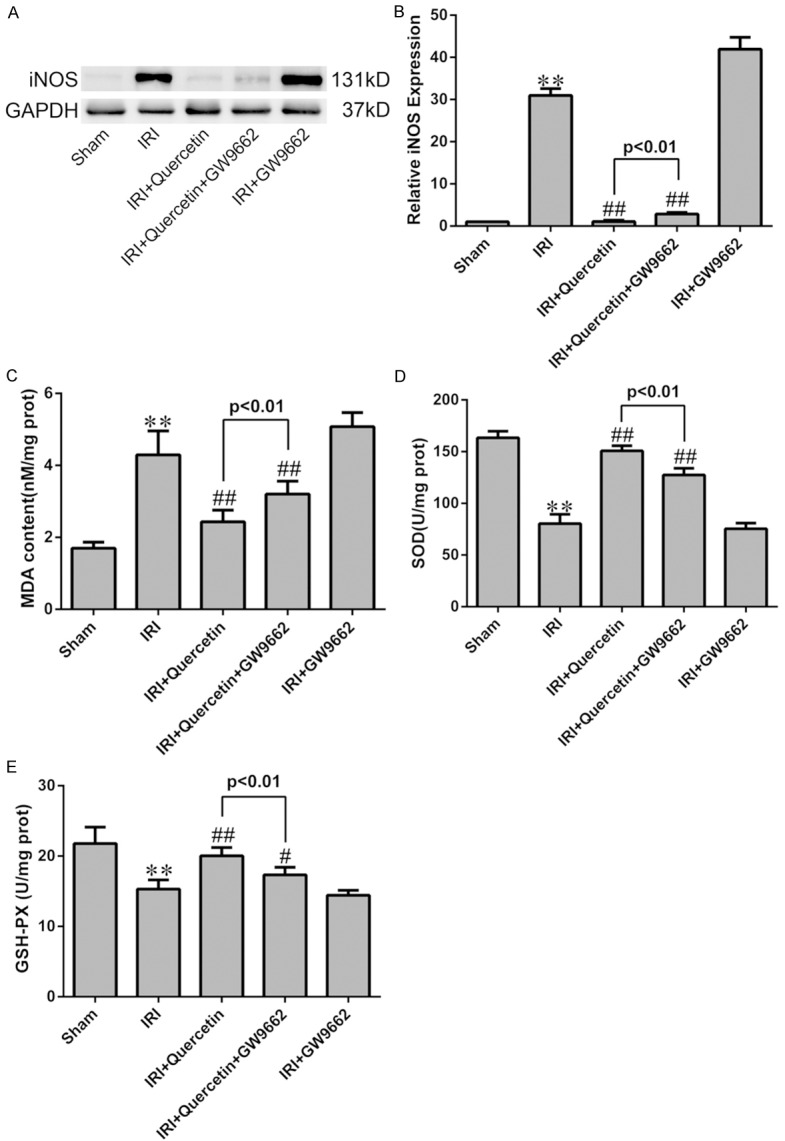

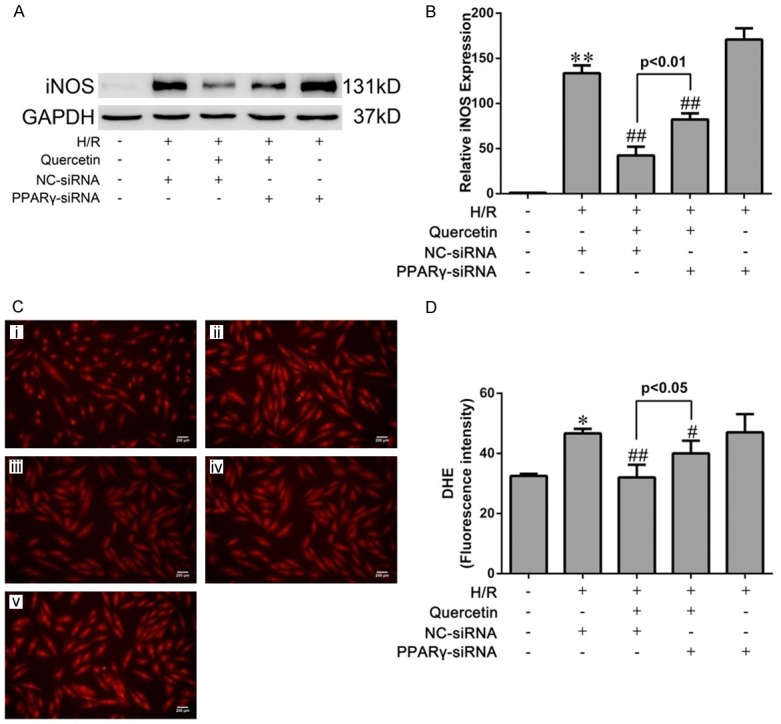

The protective effect of quercetin on myocardial oxidative damage after IRI via PPARγ in vivo and in vitro

As IRI can induce prominent oxidative stress, we attempted to investigate whether quercetin has anti-oxidative activity during myocardial IRI. To this end, we used two models, i.e., the myocardial IRI mouse model and H9C2 cells exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R). Western blot analyses revealed that the expression level of iNOS, a marker of oxidative stress [28], was increased in both models, and quercetin treatment effectively attenuated iNOS expression induced by IRI or H/R (Figures 4A, 4B, 6A and 6B).

Figure 4.

Effects of quercetin and PPARγ inhibitor on cardiomyocyte oxidative damage after IRI in vivo. (A) Western blot analysis of the expression of iNOS in IRI heart tissue. Quantification of the densitometry of western blot bands is shown in (B). Data shown represent mean ± SD. (C-E) Levels of MDA, SOD and GSH-PX were assessed in the myocardial tissues (n=6). **P<0.01 vs Sham group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs IRI group. All experiments were repeated six times.

Figure 6.

Effects of quercetin and PPARγ knockdown on cardiomyocyte oxidative damage after H/R in vitro. (A) Western blot analysis of the expression of iNOS in H9C2. Quantification of the densitometry of western blot bands is shown in (B). Data shown represent mean ± SD. (C) Representative images of DHE staining of H9C2 cells (magnification ×400). (i) H9C2 pretreated with DMSO and cultured in normoxic condition (Sham). (ii) H9C2 transfected NC-siRNA, pretreated with DMSO and suffered from H/R (H/R+NC-siRNA). (iii) H9C2 transfected NC-siRNA, pretreated with quercetin and suffered H/R (H/R+quercetin+NC-siRNA). (iv) H9C2 transfected PPARγ-siRNA, pretreated with quercetin and suffered H/R (H/R+quercetin+PPARγ-siRNA). (v) H9C2 transfected PPARγ-siRNA, pretreated with DMSO and suffered H/R (H/R+PPARγ-siRNA). (D) Quantification of DHE intensities in the indicated groups (five fields for each specimen). The values were presented as mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs Sham group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs IRI group. All experiments were repeated three times.

IRI-induced oxidative stress in mice was further evaluated by assessing the level of malondialdehyde (MDA), a product derived from lipid peroxidation [29], in myocardial tissues. Consistently, quercetin treatment almost completely abolished myocardial IRI-induced elevation of MDA level (Figure 4C). Moreover, the activities of antioxidant enzymes GSH-PX and SOD were significantly decreased in the IRI group, which was also reversed by quercetin treatment (Figure 4D, 4E). ROS generation in H9C2 cells was detected by DHE staining, which revealed that quercetin pretreatment blocked H/R-induced superoxide production (Figure 6C and 6D).

We next used PPARγ inhibition by GW9662 (for the in vivo model) and PPARγ knockdown (for the in vitro model) to assess the involvement of PPARγ in mediating quercetin’s anti-oxidative activity. Indeed, both approaches partially abolished the effects of quercetin in the above-mentioned assays (Figures 4 and 6).

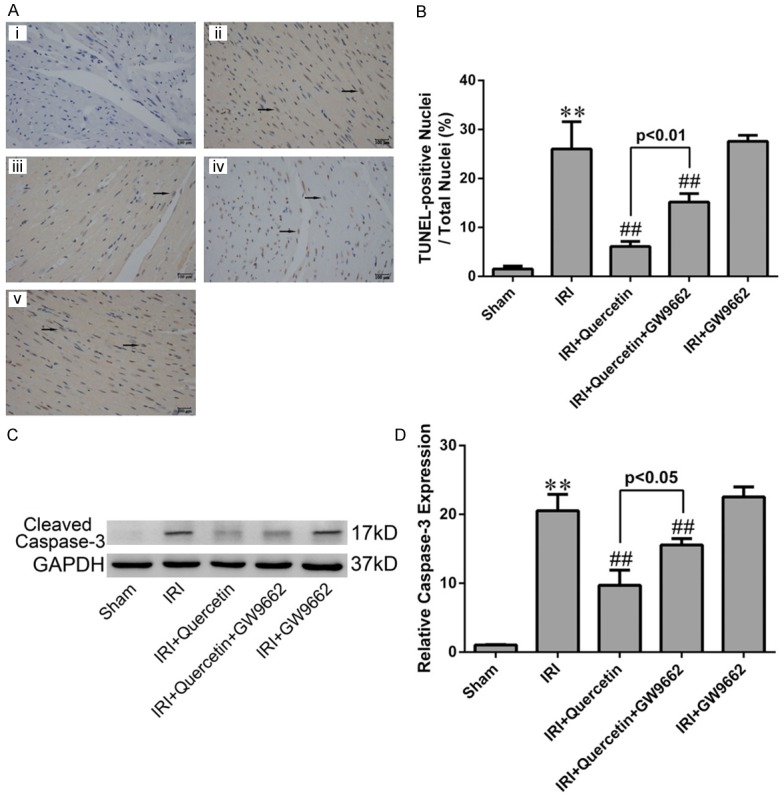

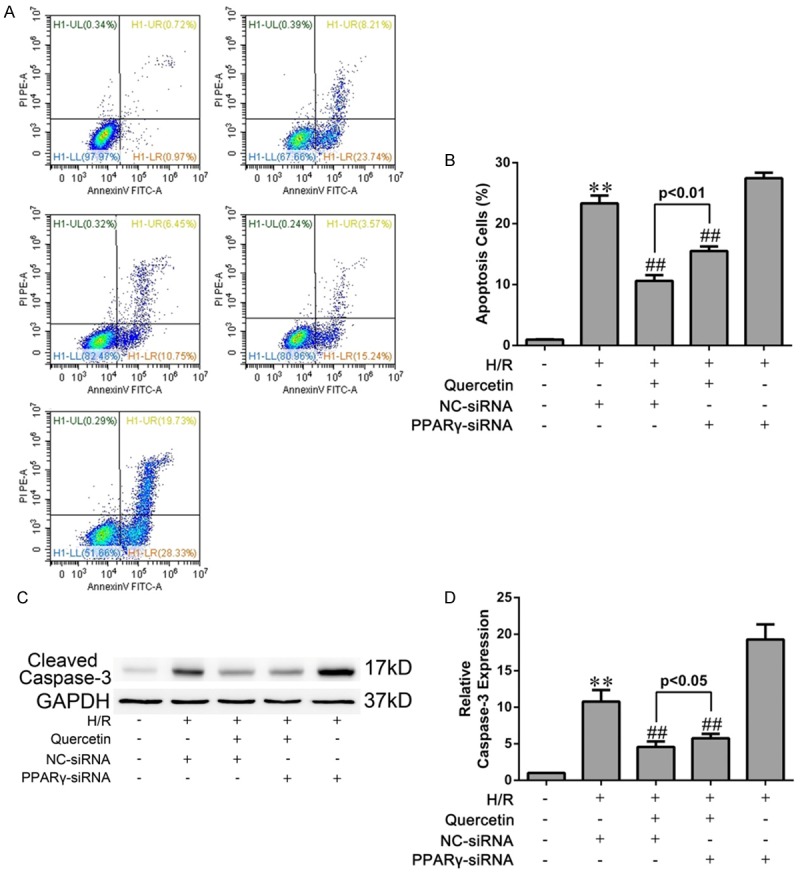

Quercetin protects myocardium from apoptosis stimulated by IRI via PPARγ in vivo and in vitro

Next we evaluated whether quercetin protected against IRI-induced apoptosis in mycardium. Both the TUNEL assay and cleaved caspase-3 analysis demonstrated the anti-apoptotic effect of quercetin in myocardial IRI mice. Inhibition of PPARγ by GW9662 attenuated the anti-apoptotic effect of quercetin (Figure 7). Similar results were obtained in H9C2 cells subjected to H/R. Both the Annexin V/PI and cleaved caspase-3 analyses showed that H/R-induced cell apoptosis was largely diminished by quercetin. Knockdown of PPARγ had a moderate, but significant, effect against quercetin’s anti-apoptotic activity in H/R-treated H9C2 cells (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Effects of quercetin and PPARγ inhibitor on cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo. (A) TUNEL staining for left ventricular tissue from different treatment groups. Nuclei with brown staining indicated TUNEL-positive cells (black arrows) and blue staining indicate TUNEL-negative cells (magnication ×400). (i) Sham-operation mice treated with vehicles (Sham). (ii) Myocardial IRI mice treated with vehicles (IRI). (iii) Myocardial IRI mice treated with quercetin (IRI+quercetin). (iv) Myocardial IRI mice treated with GW9662 and quercetin (IRI+quercetin+GW9662). (v) Myocardial IRI mice treated with GW9662 (IRI+GW9662). (B) Quatification of apoptotic rate based on TUNEL staining (five fields for each specimen). (C) Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase-3 in the indicated groups. Densitometry was shown in (D). The values were presented as mean ± SD. **P<0.01 vs Sham group; ##P<0.01 vs IRI group. All experiments were repeated six times.

Figure 8.

Effects of quercetin and PPARγ knockdown on apoptosis of H9C2 cells. A. After H/R treatment, the cells were harvested and stained with FITC-Annexin V and PI followed by analysis with flow cytometry. The percentage of Annexin V+/PI- cells from three independent experiments was shown. (i) H9C2 pretreated with DMSO and cultured in normoxic condition (Sham). (ii) H9C2 transfected NC-siRNA, pretreated with DMSO and suffered from H/R (H/R+NC-siRNA). (iii) H9C2 transfected NC-siRNA, pretreated with quercetin and suffered H/R (H/R+quercetin+NC-siRNA). (iv) H9C2 transfected PPARγ-siRNA, pretreated with quercetin and suffered H/R (H/R+quercetin+PPARγ-siRNA). (v) H9C2 transfected PPARγ-siRNA, pretreated with DMSO and suffered H/R (H/R+PPARγ-siRNA). B. Statistical data of apoptotic rate analyzed from flow cytometry. C, D. Western blot analysis of the expression of cleaved caspase-3 in H9C2 cells suffering H/R and the gray values were measured. The values were presented as mean ± SD. **P<0.01 vs Sham group; ##P<0.01 vs H/R group. All experiments were repeated three times.

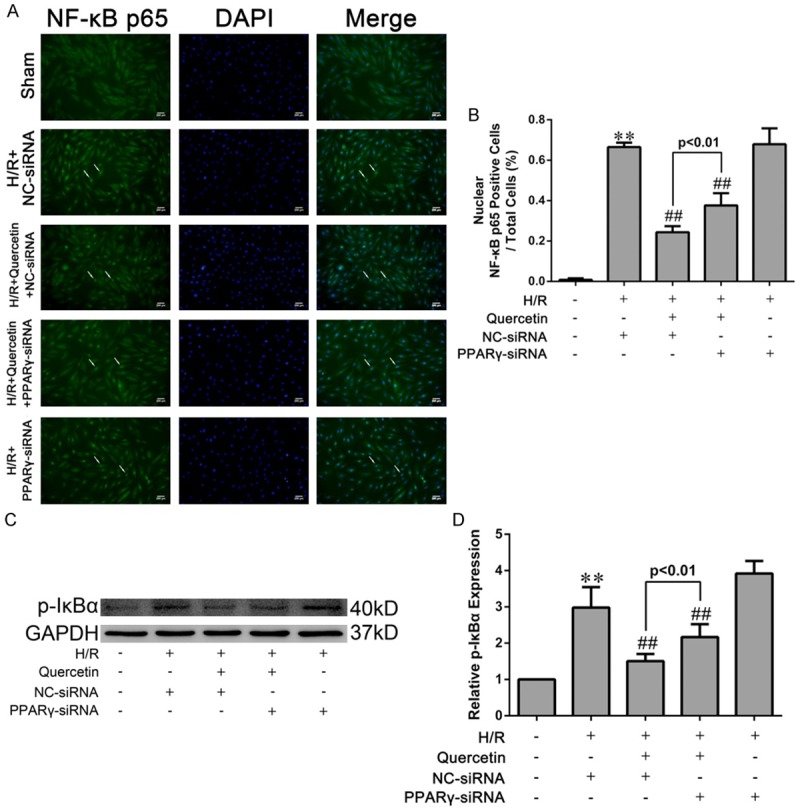

Quercetin suppressed the NF-κB pathway via PPARγ in H/R-treated H9C2 cells

Activation of the NF-κB pathway is critical in promoting myocardial inflammation during IRI [30] and its inhibition may thus underlie the cardioprotective activity of quercetin in myocardial IRI. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 subunit and p-IκBα, two major indicator for activation of the NF-κB signaling [31]. Upon exposure to H/R, H9C2 cells displayed increased levels of nuclear NF-κB p65 and p-IκBα. Pre-treatment of quercetin significantly diminished the nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65 and the expression of p-IκBα. However, these effects were partially abolished by PPARγ knockdown (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Effects of quercetin and PPARγ knockdown on activation of the NF-κB pathway in H9C2 cells. A. H9C2 cells were fixed, and immune-stained with an antibody against NF-κB p65 (1:400, green) followed by DAPI nuclear counterstaining (blue). Fluorescence microscopy coupled with image analysis was then performed (magnication ×400). B. Quantitative analysis of nuclear NF-κB p65-positive H9C2 cells (white arrows in photograph A, five fields for each specimen). C, D. Western blot analysis of the levels of IκBα phosphorylation and densitometry was measured. The values were presented as mean ± SD. **P<0.01 vs Sham group; ##P<0.01 vs H/R group. All experiments were repeated three times.

Discussion

Some scholars have documented positive effects of quercetin on cardiovascular system, such as blood pressure, left ventricular hypertrophy and anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity [32-34]. Of late years, the proposed protective effect of quercetin on the myocardial IRI has been one of the hot research areas [35].

Previous study showed that Isorhamnetin, which is an immediate metabolite of quercetin, could increase PPARγ activity and modulated the expression of PPARγ regulated genes in gastric cancer cells [36]. Furthermore, quercetin has been demonstrated to prevent H9C2 cells from Angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy by enhancing PPARγ expression during arteriosclerosis [37]. Thus, we speculated that the protective effect of quercetin on myocardial IRI might also involve in PPARγ.

It has been well known that activation of PPARγ had positive effect on cardiovascular disease, such as ventricular hypertrophy, cardiac remodeling, acute myocardial infarction [37-39] and so on. In our study, we observed decreased expression of PPARγ in myocardium suffering IRI, and quercetin could significantly increase the PPARγ expression per se. (Figure 1). This phenomenon confirmed our hypothesis in some extent and urged us to further explore the role of PPARγ in protective effect of quercetin on myocardial IRI.

In our study, after mice heart were challenged with IRI, we observed an significantly increased serum AST, CK-MB, LDH and cTnT levels and the appearance of pale area size of the heart with evans Blue/TTC staining in the model group (Figure 2). Protective effect of quercetin was manifested as decreased serum biochemical indicators levels and 60%~70% reductions in infarct size, the possible mechanism was that quercetin could enhance the anti-hypoxia capability of the heart. These beneficial effects of quercetin were reversed by GW9662, a kind of PPARγ antagonist. However, treatment of GW9662 did not completely prevent the cardioprotective effect of quercetin, we suspected that there were still other molecule and pathways involved in this effect. But these data had provided substantial support for the conclusion that quercetin could protect myocardium against IRI, and PPARγ might be involved in this process.

Then we used echocardiography to estimate LV function. The echocardiography records showed that quercetin significantly diminished the decline in EF and FS compared with the IRI group 24 h post-IRI and GW9662 could attenuate this effect (Figure 3), suggesting that PPARγ also participated in the improvement of cardiac function of quercetin.

Oxidative stress injury and apoptosis plays an important role in myocardial IRI [40], thus we needed to analyse oxidative stress and apoptosis level both in vivo and in vitro.

Our result showed that the elevated level of MDA in myocardial IRI tissue was markedly decreased by treatment with quercetin, also, quercetin was suggested to be effective in stimulating the activities of SOD and GSH-PX (Figure 4). iNOS is the key enzyme of producing the cytotoxic nitric oxide (NO), and is regarded as one of the oxidative stress injury markers. Quercetin could attenuate the increased expression of iNOS by myocardial IRI in vivo and in vitro (Figures 4 and 6). The generation of excessive ROS is well recognized as a critical primary event in myocardial IRI [41]. The burst of ROS results in myocardial damage, which might lead to cardiomyocyte cellular membrane damage, DNA oxidation and mitochondrial ultrastructure damage [42], ROS also largely contribute to myocardial apoptosis [43]. DHE staining directly revealed that quercetin could significantly reduced ROS production in H/R culture of H9C2, which contributed to the cardiac protective role of quercetin (Figure 6). Our data suggested that quercetin protected myocardial IRI through the amelioration of oxidative stress. On the other hand, GW9662 or PPARγ-siRNA reversed these effects of anti-oxidation of quercetin. Therefore, we concluded that PPARγ activation was responsible for the suppressed effect of quercetin to oxidative stress injury of myocardial IRI.

Apoptosis is a prominent factor contributing to cell death during myocardial IRI [44]. In our study, the detections of cleaved caspase-3, TUNEL and Annexin V, which are marks of apoptosis, revealed that quercetin could reduce cardiomyocyte apoptosis in vivo and in vitro, which may account for another mechanism for quercetin myocardial protection (Figures 7 and 8). Moreover, these cardioprotective effect of quercetin was diminished when PPARγ antagonist GW9662 or PPARγ-siRNA was used, indicating that quercetin reduced apoptosis in IRI myocardium via PPARγ activation.

The above observations confirmed the involvement of PPARγ in the protective effect of quercetin on myocardial IRI model in vivo and in vitro. To figure out the underlying mechanism of this, we next investigated whether the stimulation of PPARγ by quercetin controlled NF-κB pathway in H9C2 cells during myocardial IRI.

NF-κB regulates the genes of many inflammatory mediators and plays an important role in ischemic tissue damage in many organs [45], otherwise, IRI-induced activation of NF-κB could promote oxidative stress, ROS production and cardiomyocyte apoptosis after myocardial IRI [46]. Studies have demonstrated that when myocardium suffered from IRI, NF-κB pathway would be activated and facilitated the transcription of genes encoding oxidative stress and apoptosis molecules [47]. In view of the pivotal role of NF-κB pathway in myocardial IRI, we decided to introduce it into our study. PPARs are transcription factors belonging to the nuclear receptor gene family that can hetero-dimerize with the retinoid X receptor and bind to PPAR response elements (PPREs) in target gene promoters and then activated the transcription of these genes [48]. Studies have demonstrated that PPARγ could suppress the signal transduction and consequent activation of pro-inflammatory transcription factors such as NF-κB [49], thereby further inhibiting the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines, attenuating oxidative burst, inhibiting iNOS induction, and decreasing inflammation [50]. In this study, we demonstrated that pre-treatment with quercetin suppressed H/R-induced NF-κB activation on H9C2 (Figure 9). However, the inhibited effect of NF-κB pathway by quercetin was attenuated when PPARγ-siRNA was used, which indicating that quercetin prevented NF-κB activation via PPARγ in cardiomyocyte suffering H/R. This result confirmed the negative cross-talk between PPARγ and NF-κB, thus we speculated that PPARγ exerted anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic activities by negatively interfering with NF-κB pathway. However, due to the limitation of experimental techniques and other external condition, we have not yet found the exact regulatory sites of PPARγ on NF-κB pathway. Thus, the in-depth mechanism of the interaction between these two factors needs to be further characterized.

In conclusion, we firstly demonstrated the potential mechanisms of effective prevention of quercetin on myocardial IRI, namely suppressed NF-κB pathway activity via up-regulating PPARγ expression, which might help in further inhibiting the oxidative stress and apoptosis that participated in myocardial IRI. The findings of this study might shed light on the potential mechanism underlying quercetin-mediated attenuation of myocardial IRI and it might become a theoretical foundation for the clinical application of quercetin for the treatment/prevention of acute myocardial IRI.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Medicine-Engineering Cross-Research Foundation of Shanghai Jiao Tong University (YG2014ZD02).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Weir RA, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ. Epidemiology of heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction after acute myocardial infarction: prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognostic importance. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:13F–25F. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopez AD, Murray CC. The global burden of disease, 1990-2020. Nat Med. 1998;4:1241–1243. doi: 10.1038/3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitano K, Usui S, Ootsuji H, Takashima S, Kobayashi D, Murai H, Furusho H, Nomura A, Kaneko S, Takamura M. Rho-kinase activation in leukocytes plays a pivotal role in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad A, Stone GW, Holmes DR, Gersh B. Reperfusion injury, microvascular dysfunction, and cardioprotection: the “dark side” of reperfusion. Circulation. 2009;120:2105–2112. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolli R, Becker L, Gross G, Mentzer R Jr, Balshaw D, Lathrop DA. Myocardial protection at a crossroads: the need for translation into clinical therapy. Circ Res. 2004;95:125–134. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000137171.97172.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erden Inal M, Kahraman A. The protective effect of flavonol quercetin against ultraviolet a induced oxidative stress in rats. Toxicology. 2000;154:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(00)00268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee M, Son M, Ryu E, Shin YS, Kim JG, Kang BW, Cho H, Kang H. Quercetin-induced apoptosis prevents EBV infection. Oncotarget. 2015;6:12603–12624. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin HB, Yang YB, Song YL, Zhang YC, Li YR. Protective roles of quercetin in acute myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury in rats. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:11005–11009. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-2002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee SM, Moon J, Cho Y, Chung JH, Shin MJ. Quercetin up-regulates expressions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, liver X receptor alpha, and ATP binding cassette transporter A1 genes and increases cholesterol efflux in human macrophage cell line. Nutr Res. 2013;33:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy GJ, Holder JC. PPAR-gamma agonists: therapeutic role in diabetes, inflammation and cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:469–474. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01559-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimabukuro M, Higa S, Shinzato T, Nagamine F, Komiya I, Takasu N. Cardioprotective effects of troglitazone in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Metabolism. 1996;45:1168–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giaginis C, Tsourouflis G, Theocharis S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) ligands: novel pharmacological agents in the treatment of ischemia reperfusion injury. Curr Mol Med. 2008;8:562–579. doi: 10.2174/156652408785748022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q, Tang XN, Yenari MA. The inflammatory response in stroke. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramachandran S, Liaw JM, Jia J, Glasgow SC, Liu W, Csontos K, Upadhya GA, Mohanakumar T, Chapman WC. Ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat steatotic liver is dependent on NFkappaB P65 activation. Transpl Immunol. 2012;26:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surh YJ, Kundu JK, Na HK, Lee JS. Redox-sensitive transcription factors as prime targets for chemoprevention with anti-inflammatory and antioxidative phytochemicals. J Nutr. 2005;135:2993S–3001S. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.12.2993S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan MJ, Liu ZG. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-kappaB signaling. Cell Res. 2011;21:103–115. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon JW, Shaw JA, Kirshenbaum LA. Multiple facets of NF-kappaB in the heart: to be or not to NF-kappaB. Circ Res. 2011;108:1122–1132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takahashi Y, Ganster RW, Gambotto A, Shao L, Kaizu T, Wu T, Yagnik GP, Nakao A, Tsoulfas G, Ishikawa T, Okuda T, Geller DA, Murase N. Role of NF-kappaB on liver cold ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G1175–1184. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00515.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Remels AH, Langen RC, Gosker HR, Russell AP, Spaapen F, Voncken JW, Schrauwen P, Schols AM. PPARgamma inhibits NF-kappaB-dependent transcriptional activation in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E174–183. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90632.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scirpo R, Fiorotto R, Villani A, Amenduni M, Spirli C, Strazzabosco M. Stimulation of nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma limits NF-kappaB-dependent inflammation in mouse cystic fibrosis biliary epithelium. Hepatology. 2015;62:1551–1562. doi: 10.1002/hep.28000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou Y, Moreau F, Chadee K. PPARgamma is an E3 ligase that induces the degradation of NFkappaB/p65. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1300. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan SZ, Usher MG, Mortensen RM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-mediated effects in the vasculature. Circ Res. 2008;102:283–294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu H, Guo X, Chu Y, Lu S. Heart protective effects and mechanism of quercetin preconditioning on anti-myocardial ischemia reperfusion (IR) injuries in rats. Gene. 2014;545:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agrawal YO, Sharma PK, Shrivastava B, Ojha S, Upadhya HM, Arya DS, Goyal SN. Hesperidin produces cardioprotective activity via PPAR-gamma pathway in ischemic heart disease model in diabetic rats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haubner BJ, Neely GG, Voelkl JG, Damilano F, Kuba K, Imai Y, Komnenovic V, Mayr A, Pachinger O, Hirsch E, Penninger JM, Metzler B. PI3Kgamma protects from myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury through a kinase-independent pathway. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li C, Wang T, Zhang C, Xuan J, Su C, Wang Y. Quercetin attenuates cardiomyocyte apoptosis via inhibition of JNK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways. Gene. 2016;577:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fishbein MC, Meerbaum S, Rit J, Lando U, Kanmatsuse K, Mercier JC, Corday E, Ganz W. Early phase acute myocardial infarct size quantification: validation of the triphenyl tetrazolium chloride tissue enzyme staining technique. Am Heart J. 1981;101:593–600. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(81)90226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spitaler MM, Graier WF. Vascular targets of redox signalling in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2002;45:476–494. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Draper HH, Hadley M. Malondialdehyde determination as index of lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:421–431. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86135-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawamura N, Kubota T, Kawano S, Monden Y, Feldman AM, Tsutsui H, Takeshita A, Sunagawa K. Blockade of NF-kappaB improves cardiac function and survival without affecting inflammation in TNF-alpha-induced cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:520–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa] B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards RL, Lyon T, Litwin SE, Rabovsky A, Symons JD, Jalili T. Quercetin reduces blood pressure in hypertensive subjects. J Nutr. 2007;137:2405–2411. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ulasova E, Perez J, Hill BG, Bradley WE, Garber DW, Landar A, Barnes S, Prasain J, Parks DA, Dell’Italia LJ, Darley-Usmar VM. Quercetin prevents left ventricular hypertrophy in the Apo E knockout mouse. Redox Biol. 2013;1:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Czepas J, Gwozdzinski K. The flavonoid quercetin: possible solution for anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity and multidrug resistance. Biomed Pharmacother. 2014;68:1149–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen YW, Chou HC, Lin ST, Chen YH, Chang YJ, Chen L, Chan HL. Cardioprotective Effects of Quercetin in Cardiomyocyte under Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:364519. doi: 10.1155/2013/364519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramachandran L, Manu KA, Shanmugam MK, Li F, Siveen KS, Vali S, Kapoor S, Abbasi T, Surana R, Smoot DT, Ashktorab H, Tan P, Ahn KS, Yap CW, Kumar AP, Sethi G. Isorhamnetin inhibits proliferation and invasion and induces apoptosis through the modulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation pathway in gastric cancer. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:38028–38040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.388702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan L, Zhang JD, Wang B, Lv YJ, Jiang H, Liu GL, Qiao Y, Ren M, Guo XF. Quercetin inhibits left ventricular hypertrophy in spontaneously hypertensive rats and inhibits angiotensin II-induced H9C2 cells hypertrophy by enhancing PPAR-gamma expression and suppressing AP-1 activity. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qi HP, Wang Y, Zhang QH, Guo J, Li L, Cao YG, Li SZ, Li XL, Shi MM, Xu W, Li BY, Sun HL. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) through NF-kappaB/Brg1 and TGF-beta1 pathways attenuates cardiac remodeling in pressure-overloaded rat hearts. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:899–912. doi: 10.1159/000369747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu DY, Davis BB, Wang ZH, Zhao SP, Wasti B, Liu ZL, Li N, Morisseau C, Chiamvimonvat N, Hammock BD. A potent soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitor, t-AUCB, acts through PPARgamma to modulate the function of endothelial progenitor cells from patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1298–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao GL, Yu LM, Gao WL, Duan WX, Jiang B, Liu XD, Zhang B, Liu ZH, Zhai ME, Jin ZX, Yu SQ, Wang Y. Berberine protects rat heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury via activating JAK2/STAT3 signaling and attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37:354–367. doi: 10.1038/aps.2015.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashraf MI, Ebner M, Wallner C, Haller M, Khalid S, Schwelberger H, Koziel K, Enthammer M, Hermann M, Sickinger S, Soleiman A, Steger C, Vallant S, Sucher R, Brandacher G, Santer P, Dragun D, Troppmair J. A p38MAPK/MK2 signaling pathway leading to redox stress, cell death and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cell Commun Signal. 2014;12:6. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-12-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalogeris T, Bao Y, Korthuis RJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: a double edged sword in ischemia/reperfusion vs preconditioning. Redox Biol. 2014;2:702–714. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1121–1135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao H, Jaffer T, Eguchi S, Wang Z, Linkermann A, Ma D. Role of necroptosis in the pathogenesis of solid organ injury. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1975. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Sun Z, Shen J, Wu D, Liu F, Yang R, Ji S, Ji A, Li Y. Octreotide Protects the Mouse Retina against Ischemic Reperfusion Injury through Regulation of Antioxidation and Activation of NF-kappaB. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:970156. doi: 10.1155/2015/970156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright CJ, Agboke F, Muthu M, Michaelis KA, Mundy MA, La P, Yang G, Dennery PA. Nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) inhibitory protein IkappaBbeta determines apoptotic cell death following exposure to oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6230–6239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.318246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu T, Li D, Jiang D. Targeting cell signaling and apoptotic pathways by luteolin: cardioprotective role in rat cardiomyocytes following ischemia/reperfusion. Nutrients. 2012;4:2008–2019. doi: 10.3390/nu4122008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoonjans K, Martin G, Staels B, Auwerx J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, orphans with ligands and functions. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1997;8:159–166. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199706000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scirpo R, Fiorotto R, Villani A, Amenduni M, Spirli C, Strazzabosco M. Stimulation of nuclear receptor PPAR-gamma limits NF-kB-dependent inflammation in mouse cystic fibrosis biliary epithelium. Hepatology. 2015;62:1551–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.28000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mersmann J, Tran N, Zacharowski PA, Grotemeyer D, Zacharowski K. Rosiglitazone is cardioprotective in a murine model of myocardial I/R. Shock. 2008;30:64–68. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31815dbdc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]