Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is associated with a reduced risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Epidemiological studies examining the association between NSAID use and the risk of the precursor lesion, Barrett's esophagus, have been inconclusive.

METHODS

We analyzed pooled individual-level participant data from six case-control studies of Barrett's esophagus in the Barrett's and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Consortium (BEACON). We compared medication use from 1474 patients with Barrett's esophagus separately with two control groups: 2256 population-based controls and 2018 gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) controls. Study-specific odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using multivariable logistic regression models and were combined using a random effects meta-analytic model.

RESULTS

Regular (at least once weekly) use of any NSAIDs was not associated with the risk of Barrett's esophagus (vs. population-based controls, adjusted OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.76–1.32; I2=61%; vs. GERD controls, adjusted OR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.82–1.19; I2=19%). Similar null findings were observed among individuals who took aspirin or non-aspirin NSAIDs. We also found no association with highest levels of frequency (at least daily use) and duration (≥5 years) of NSAID use. There was evidence of moderate between-study heterogeneity; however, associations with NSAID use remained non-significant in “leave-one-out” sensitivity analyses.

CONCLUSIONS

Use of NSAIDs was not associated with the risk of Barrett's esophagus. The previously reported inverse association between NSAID use and esophageal adenocarcinoma may be through reducing the risk of neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett's esophagus.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has increased more than eightfold in the United States in recent decades (1), and the incidence continues to rise (2). Esophageal adenocarcinoma is a highly fatal cancer with a five-year survival rate of < 20% (3). Thus, as with other aggressive cancers, there is strong interest in identifying chemopreventive agents that might help reduce the burden of esophageal adenocarcinoma, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), statins, or acid suppressant medications.

NSAIDs have been shown in experimental studies to have a chemopreventive effect on the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma, presumably by blocking cyclooxygenase (COX) isoenzymes (aspirin is an inhibitor of COX-1, while other NSAIDs block both COX-1 and COX-2) and the production of prostaglandin. In addition, epidemiological studies have found a strong inverse association between use of NSAIDs and the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. In a pooled analysis of data from the Barrett's and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Consortium (BEACON; http://beacon.tlvnet.org/), Liao et al. (4) showed that patients who used any NSAIDs had a 32% reduced risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma (summary adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 0.68, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.56–0.83; I2=17%).

Barrett's esophagus is the only known precursor for esophageal adenocarcinoma and may affect 2% of the general adult population (5). Compared to the general population, patients with Barrett's esophagus have 10- to 55-fold increased risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma (6-11). Assessment of risk factors for Barrett's esophagus may allow for better understanding of disease pathophysiology, and identify new opportunities for prevention and risk stratification. While NSAIDs have been consistently associated with reduced risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma, it is unclear whether they may affect risk through preventing the development of Barrett's esophagus, by preventing the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett's esophagus, or both. This question has substantial clinical implications, because attempts at chemoprevention with NSAIDs in the setting of Barrett's esophagus are only logical if the effect of NSAIDs occurs after the development of Barrett's esophagus. A recent meta-analysis of five studies showed a 30% reduction in the risk of progression from Barrett's esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma among NSAID users, as compared with nonusers (12). In contrast, results from epidemiological studies of the association between NSAIDs and the risk of Barrett's esophagus have been largely inconclusive, where both negative (13-15) and positive associations (16,17) have been reported.

We therefore conducted a large analysis of pooled individual-level data from six case-control studies in the BEACON Consortium to comprehensively examine the association between use of NSAIDs and the risk of Barrett's esophagus.

METHODS

Study population

We analyzed individual-level participant data from six population-based case-control studies in BEACON that had available data on NSAID use (Supplementary Table 1). The six studies were as follows: the Houston Barrett's Esophagus study (based at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center at Houston, TX; hereafter “Houston”) (17); the Factors Influencing the Barrett's/Adenocarcinoma Relationship study (based in Ireland; “FINBAR”) (13); the Epidemiology and Incidence of Barrett's Esophagus study (based in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California population; “KPNC”) (14); The Newly Diagnosed Barrett's Esophagus Study (based at the University of Michigan and Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Medical Center at Ann Arbor, MI; “NDB”) (18); the Study of Digestive Health (based in Brisbane, Australia; “SDH”) (16); and the Study of Reflux Disease (based in western Washington State; “SRD”) (19). We additionally restricted our analyses to non-Hispanic white study participants due to low numbers of cases from non-white ethnic groups (total n=95; range n=17 in NDB to n=43 in KPNC). The Institutional Review Boards or Research Ethics Committees of each institution approved the acquisition and pooling of data for the present analysis. Participants provided written informed consent to take part in the studies.

In all studies, cases included persons with endoscopic evidence of columnar mucosa in the tubular esophagus, accompanied by the presence of specialized intestinal metaplasia in an esophageal biopsy, and cases included persons with prevalent and newly diagnosed Barrett's esophagus (Supplementary Table 1). The SRD also included some patients with specialized intestinal esophageal metaplasia on biopsy, but without endoscopically visible columnar metaplasia. The NDB study included only males (cases and controls) (18).

The cases were compared separately with (1) population-based controls, representing the underlying source population from which cases arose, and (2) gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) controls, representing the population undergoing endoscopy from which cases are diagnosed.

Study variables

Data for medication use was self-reported in all studies (Supplementary Table 1). Five of the six studies asked about “regular use” of medications over a specified time period with a minimum frequency of use (13,14,17-19). The duration of regular use varied across the five studies, from 3 months to 1 year of use. The definition for frequency of regular use was consistent across the five studies, each specified as at least once per week. The remaining study did not define regular use; for this study we reclassified study participants as regular users if their reported frequency of use was at least once per week (16).

The main exposure categories used in the analysis were regular (at least once per week) use of the medication (aspirin, non-aspirin NSAIDs, any NSAIDs) and non-regular use (referent group; less than once per week use for each category). Medication use was further classified by frequency (weekly—<daily and at least daily) and duration (< 5 years and ≥ 5 years) of use.

Potential confounding variables were available from all studies as part of a core dataset and were harmonized by the coordinating center. Variables that were selected a priori as adjustment factors included age (<50, 50−<60, 60−<70, ≥70 years), sex (except for NDB which included only males), highest level of education (school only, tech/diploma, university), smoking status (never, former, current) and body mass index (BMI; <25, 25-29.9, ≥30 kg/m2). Models that compared cases with population-based controls were also subsequently adjusted for self-reported GERD symptoms (less than weekly vs. at least weekly) to evaluate potential confounding effects of GERD symptoms. Frequency of GERD symptoms was defined as the highest reported frequency of either heartburn or acid regurgitation symptoms; “frequent symptoms” were those occurring at least weekly.

Statistical analysis

We used multivariable logistic regression to estimate study-specific ORs and 95% CIs for the association between NSAID use and risk of Barrett's esophagus. The study-specific ORs were then combined using random-effects meta-analytic models to generate a summary OR. We used the inconsistency index, I2, and its 95% uncertainty interval (UI) to assess heterogeneity between studies (20). Larger I2 values reflect increasing heterogeneity, beyond what is attributable to chance. I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% were used as evidence of low, moderate, or high levels of heterogeneity, respectively. A leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed by iteratively removing one study at a time to assess whether a single study was contributing to high (if present) between-study heterogeneity and to confirm that our findings were not driven by any single study (21). For comparisons with population-based controls only, we assessed whether the association between NSAID use and the risk of Barrett's esophagus was modified by frequency of GERD symptoms (less than weekly, at least weekly) by performing likelihood ratio tests of nested models with and without the NSAID-GERD interaction term.

All tests for statistical significance were two-sided at α=0.05 and analyses were conducted using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We included data from 1474 cases, 2256 population-based controls and 2018 GERD controls in the analysis. In total, 31.7% of the study population reported regular (at least once weekly) use of aspirin, 19.6% reported regular use of non-aspirin NSAIDs, and 47.0% reported regular use of any NSAIDs. However, the prevalence of use among controls (and cases) varied considerably across the six studies (Supplementary Table 2). For example, prevalence of prior regular use of aspirin in population-based controls ranged from 10.7% in SDH to 47.3% in NDB; in cases, from 17.0% in SDH to 49.6% in NDB.

Aspirin

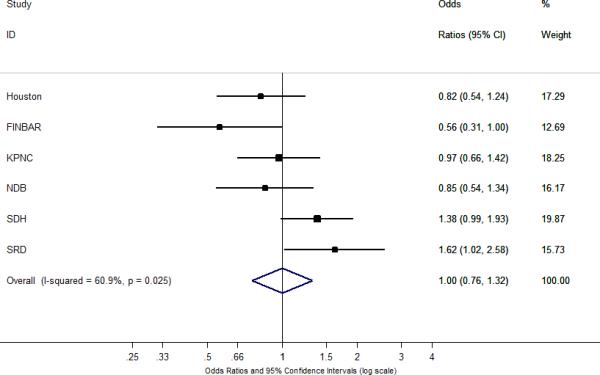

Figure 1A shows the association between aspirin use and risk of Barrett's esophagus. In the multivariable analysis, there was no association between prior regular use of aspirin (fully adjusted OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.76–1.32) and the risk of Barrett's esophagus for comparison with population-based controls (Table 1). We found moderate between-study heterogeneity (I2=56%), but with a wide uncertainty interval (95% UI = 0%–82%). Among five studies that reported information on frequency of use (SDH did not capture daily medication use), prior daily use of any aspirin was not associated with the risk of Barrett's esophagus (fully adjusted OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.71–1.21), with no evidence of between-study heterogeneity (I2=10%). With regard to duration of use (Table 1), we found no association between duration of prior aspirin use and risk of Barrett's esophagus (fully adjusted OR for ≥ 5 years = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.70–1.54; I2=59%). We found similar null findings for aspirin use when we compared cases with GERD controls (Table 2) and in analyses (cases vs. population-based controls) stratified by frequency of GERD symptoms (Table 3).

Figure 1. Associations between NSAID use and risk of Barrett's esophagus.

The summary odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between Barrett's esophagus and A) at least weekly aspirin use; B) at least weekly non-aspirin NSAID use; and C) at least weekly use of any NSAIDs. Summary odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated using a random-effects meta-analytic model. All statistical tests were two-sided. % Weight describes the weighting each study contributes to the summary odds ratio. The dot on each square represents the study-specific odds ratio, and the size of the surrounding square is an illustrative representation of study weighting. The horizontal lines represent the confidence intervals; if ending in an arrow, this indicates that the interval transcends the region plotted. The diamond represents the summary odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals. Houston = the Houston Barrett's Esophagus study; FINBAR = Factors Influencing the Barrett's Adenocarcinoma Relationship Study; KPNC = the Epidemiology and Incidence of Barrett's Esophagus study; NDB = The Newly Diagnosed Barrett's Esophagus Study; SDH = the Study of Digestive Health; SRD = the Study of Reflux Disease.

Table 1.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for the Association Between Frequency of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Use and Risk of Barrett's Esophagus Compared with Population-based Controls

| No. of studies | OR (95% CI) | I2 (95% UI) | ORa (95% CI) | I2 (95% UI) | ORb (95% CI) | I2 (95% UI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin use | |||||||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| At least weekly | 6 | 1.09 (0.84-1.43) | 66 (18-87) | 1.02 (0.80-1.29) | 50 (0-80) | 1.00 (0.76-1.32) | 56 (0-82) |

| Weekly-<daily | 5 | 1.11 (0.78-1.56) | 14 (0-82) | 1.02 (0.73-1.42) | 8 (0-81) | 0.88 (0.62-1.26) | 6 (0-80) |

| At least daily | 5 | 0.96 (0.74-1.26) | 35 (0-76) | 0.90 (0.72-1.13) | 2 (0-80) | 0.93 (0.71-1.21) | 10 (0-81) |

| Duration of use | |||||||

| <5 years | 5 | 0.93 (0.74-1.17) | 0 (0-34) | 0.85 (0.67-1.09) | 0 (0-40) | 0.81 (0.62-1.06) | 0 (0-67) |

| ≥5 years | 5 | 1.09 (0.76-1.57) | 64 (6-86) | 1.05 (0.71-1.55) | 65 (7-87) | 1.04 (0.70-1.54) | 59 (0-85) |

| Non-aspirin NSAID use | |||||||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| At least weekly | 6 | 1.34 (1.01-1.78) | 58 (0-83) | 1.20 (0.89-1.62) | 57 (0-83) | 1.16 (0.86-1.56) | 49 (0-80) |

| Weekly-<daily | 5 | 1.18 (0.63-2.23) | 68 (18-88) | 0.99 (0.50-1.98) | 70 (22-88) | 0.97 (0.50-1.89) | 64 (4-86) |

| At least daily | 5 | 1.51 (1.04-2.21) | 39 (0-78) | 1.42 (0.95-2.12) | 41 (0-78) | 1.42 (0.92-2.18) | 37 (0-76) |

| Duration of use | |||||||

| <5 years | 5 | 1.13 (0.81-1.57) | 34 (0-75) | 1.04 (0.79-1.36) | 0 (0-79) | 1.02 (0.77-1.37) | 0 (0-78) |

| ≥5 years | 5 | 1.76 (1.27-2.43) | 9 (0-81) | 1.63 (1.10-2.43) | 28 (0-72) | 1.57 (1.09-2.26) | 7 (0-81) |

| Any NSAID use | |||||||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| At least weekly | 6 | 1.14 (0.85-1.53) | 74 (41-87) | 1.04 (0.81-1.34) | 61 (4-84) | 1.00 (0.76-1.32) | 61 (4-84) |

| Weekly-<daily | 5 | 1.05 (0.64-1.72) | 64 (5-86) | 0.92 (0.55-1.56) | 65 (8-87) | 0.84 (0.49-1.42) | 59 (0-85) |

| At least daily | 5 | 1.14 (0.78-1.66) | 70 (23-88) | 1.04 (0.74-1.46) | 58 (0-84) | 1.01 (0.69-1.47) | 57 (0-84) |

| Duration of use | |||||||

| <5 years | 5 | 0.92 (0.74-1.14) | 0 (0-71) | 0.84 (0.67-1.06) | 0 (0-46) | 0.80 (0.62-1.03) | 0 (0-70) |

| ≥5 years | 5 | 1.17 (0.74-1.84) | 80 (52-91) | 1.10 (0.69-1.73) | 77 (44-91) | 1.05 (0.67-1.64) | 71 (26-89) |

Models included terms for age (<50, 50-59, 60-69, ≥70 years), sex (except NDB, all male), education (school only, tech/diploma, university), smoking status (never, former, current) and body mass index (<25, 25-29.9, ≥30 kg/m2).

Models adjusted for same factors as (a) but also GERD symptoms (less than weekly, at least weekly).

Table 2.

Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for the Association Between Frequency of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Use and Risk of Barrett's Esophagus Compared with GERD Controls

| No. of studies | OR (95% CI) | I2 (95% UI) | ORa (95% CI) | I2 (95% UI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin use | |||||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| At least weekly | 5 | 1.18 (0.92-1.52) | 57 (0-84) | 1.04 (0.82-1.30) | 40 (0-78) |

| Weekly-<daily | 4 | 1.17 (0.83-1.64) | 13 (0-87) | 1.06 (0.78-1.46) | 2 (0-85) |

| At least daily | 4 | 0.97 (0.61-1.54) | 72 (21-90) | 0.83 (0.51-1.33) | 69 (11-89) |

| Duration of use | |||||

| <5 years | 4 | 0.98 (0.61-1.58) | 74 (26-91) | 0.89 (0.53-1.48) | 75 (30-91) |

| ≥5 years | 4 | 1.27 (1.02-1.59) | 0 (0-78) | 1.14 (0.90-1.45) | 0 (0-73) |

| Non-aspirin NSAID use | |||||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| At least weekly | 5 | 0.92 (0.69-1.23) | 51 (0-82) | 0.94 (0.76-1.16) | 3 (0-80) |

| Weekly-<daily | 4 | 0.85 (0.62-1.15) | 0 (0-82) | 0.85 (0.62-1.18) | 0 (0-80) |

| At least daily | 4 | 0.89 (0.56-1.43) | 54 (0-85) | 0.93 (0.62-1.39) | 32 (0-76) |

| Duration of use | |||||

| <5 years | 4 | 0.83 (0.58-1.17) | 30 (0-74) | 0.84 (0.62-1.13) | 0 (0-83) |

| ≥5 years | 4 | 0.97 (0.71-1.32) | 0 (0-64) | 1.00 (0.72-1.38) | 0 (0-73) |

| Any NSAID use | |||||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| At least weekly | 5 | 1.07 (0.86-1.34) | 52 (0-82) | 0.99 (0.82-1.19) | 19 (0-83) |

| Weekly-<daily | 4 | 1.05 (0.81-1.36) | 0 (0-39) | 1.00 (0.76-1.31) | 0 (0-17) |

| At least daily | 4 | 0.99 (0.71-1.38) | 59 (0-86) | 0.90 (0.68-1.20) | 37 (0-78) |

| Duration of use | |||||

| <5 years | 4 | 0.84 (0.62-1.14) | 44 (0-81) | 0.79 (0.56-1.10) | 48 (0-83) |

| ≥5 years | 4 | 1.12 (0.90-1.39) | 0 (0-74) | 1.03 (0.82-1.29) | 0 (0-57) |

Models included terms for age (<50, 50-59, 60-69, ≥70 years), sex (except NDB, all male), education (school only, tech/diploma, university), smoking status (never, former, current) and body mass index (<25, 25-29.9, ≥30 kg/m2).

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals for the Association Between Frequency of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Use and Risk of Barrett's Esophagus Compared with Population-based Controls, Stratified by GERD Symptoms

| No. of studies | OR (95% CI) | I2 (95% UI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than weekly GERD symptoms | |||

| Aspirin use | |||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | ||

| At least weekly | 6 | 1.06 (0.66-1.70) | 40 (0-76) |

| Non-aspirin NSAID use | |||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | ||

| At least weekly | 6 | 1.13 (0.47-2.71) | 61 (6-84) |

| Any NSAID use | |||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | ||

| At least weekly | 6 | 0.94 (0.53-1.65) | 57 (0-83) |

| At least weekly GERD symptoms | |||

| Aspirin use | |||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | ||

| At least weekly | 6 | 0.98 (0.73-1.32) | 36 (0-74) |

| Non-aspirin NSAID use | |||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | ||

| At least weekly | 6 | 1.30 (0.99-1.70) | 16 (0-79) |

| Any NSAID use | |||

| Nonuser (< weekly use) | 1.00 | ||

| At least weekly | 6 | 1.12 (0.88-1.42) | 17 (0-62) |

Models included terms for age (<50, 50-59, 60-69, ≥70 years), sex (except NDB, all male), education (school only, tech/diploma, university), smoking status (never, former, current), and body mass index (<25, 25-29.9, ≥30 kg/m2)

Non-aspirin NSAIDs

When compared with population-based controls, regular use of any non-aspirin NSAIDs was not associated with the risk of Barrett's esophagus (fully adjusted OR = 1.16, 0.86–1.56; I2=49%) (Figure 1B). We found no evidence of effect modification by frequency of GERD symptoms (Table 3). Among the five studies that reported information on frequency and duration of use, we found some evidence for a modest increased risk of Barrett's esophagus associated with prior daily use of any non-aspirin NSAIDs (fully adjusted OR = 1.42, 95% CI = 0.92–2.18; I2=37%) and ≥ 5 years of non-aspirin NSAID use (fully adjusted OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.09–2.26; I2=7%). However, there were no associations between frequency and duration of non-aspirin NSAID use and the risk of Barrett's esophagus for comparisons with GERD controls (Table 2).

Any NSAIDs

Using data from the six studies, there was no association between regular use of any NSAIDs (adjusted OR = 1.00, 0.76–1.32; I2=61%) and the risk of Barrett's esophagus for comparison with population-based controls (Table 1). There was no association between daily use of any NSAIDs and Barrett's esophagus (fully adjusted OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.69–1.47; I2=57%). With regard to duration of use (Table 1), we found no association between duration of prior NSAID use and risk of Barrett's esophagus (fully adjusted OR for ≥ 5 years = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.67–1.64; I2=71%). We found similar null findings when we compared cases with GERD controls (Table 2) and in analyses (cases vs. population-based controls) stratified by frequency of GERD symptoms (Table 3).

While there was evidence of between-study heterogeneity for associations between NSAID use and the risk of Barrett's esophagus, the results remained unchanged in the leave-one-out analysis (Supplementary Table 3), indicating that our results were not driven by any single study.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this pooled analysis is the largest evaluation of NSAID use and risk of Barrett's esophagus to date. It included six well-characterized population-based case-control studies with similar assessments of regular medication use. We observed no overall association between regular use of any NSAIDs, as well as for the individual effects of aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs, and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. Furthermore, we found no evidence of an inverse relationship between increased frequency or duration of NSAID use and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. We did observe a moderate level of heterogeneity among the studies for many of the effect estimates, but with wide uncertainty intervals, and the associations with NSAID use remained non-significant when individual studies were omitted following “leave-one-out” analyses.

There is consistent evidence from epidemiological studies for an inverse relationship between use of NSAIDs and the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. In the largest study to date, pooled analyses of data from BEACON showed greater than 30% reduction in the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma among NSAID users, as compared with nonusers (4). The association between NSAID use and esophageal adenocarcinoma was especially strong among daily users (adjusted OR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.43–0.73; I2=0%). However, there remained considerable uncertainty regarding the stage(s) of neoplastic progression in which NSAIDs may act, whether in preventing the development of Barrett's esophagus, preventing progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett's esophagus, or both.

Several well designed prospective and retrospective studies have examined the association between NSAID use and risk of progression from Barrett's esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma. In their recent meta-analysis examining the association with NSAID use, Zhang et al. (12) showed a 30% reduction in the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett's esophagus (adjusted OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.52–0.95) with minimal heterogeneity between the five studies (I2 = 28%). They found no significant differences in the magnitude in the association with aspirin use or non-aspirin NSAID use and the association was independent of duration of use.

While several observational studies have assessed the association between NSAID use and the risk of Barrett's esophagus, the results have been inconclusive. The reasons for the contrasting results are not clear and differences in populations and methods make direct comparisons between published studies difficult. We attempted to overcome some of these shortcomings by using harmonized data from multiple well-conducted case-control studies and meta-analytic methods. Regardless, we observed a wide range of results for each of the studies included in this analysis, with results from FINBAR and SRD at the opposite extremes. The studies in BEACON were conducted in different countries, over different time periods (from 1997 to 2013), and used different questionnaires for ascertainment of medication use; all of which could have contributed to these differences in reported effect sizes. Along these lines, it is worth noting that self-reported prevalence of NSAID use among population controls varied from 20% in SDH to over 60% in NDB and the Houston study. However, in a series of sensitivity analyses (based on study period, recent vs. lifetime use) and in the leave-one-out analysis, the null findings were essentially unchanged.

Intriguingly, while we consistently found no association with aspirin use, we observed some evidence for higher risk of Barrett's esophagus associated with both daily use and use greater than 5 years of non-aspirin NSAIDs. It is not clear why there would be a difference in associations with non-aspirin NSAIDs and aspirin; it is possible that there may be some kind of interplay between prostaglandins, which causes inflammation, changes in DNA, and increased carcinogenesis. Alternatively, the non-aspirin NSAID association may in part be due to alternate prescribing trends for the cases (who are more likely to have GERD symptoms and be obese), taking non-aspirin NSAIDs as a substitute for aspirin because they are milder on the stomach.

It is biologically plausible that NSAID use may reduce risk of neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett's esophagus. NSAID use is associated with a reduction in the risk of other gastrointestinal cancers, and also reduces the rate of cancer progression in precancerous lesions. These effects are postulated to occur by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzyme production and retarding tumor growth promoted by prostaglandins (22,23). Studies have shown elevated COX-2 expression in Barrett's esophagus, and also increased COX-2 expression associated with neoplastic progression from Barrett's esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma (24,25). Furthermore, experimental studies have found that treating Barrett's esophagus cells with COX-2 inhibitors can inhibit cell growth (26,27). However, data are limited in humans and we await the results of the ASPECT trial which randomized patients with Barrett's esophagus to aspirin and proton pump inhibitors with a view to inhibiting cancer (28).

The results from our study have implications for chemoprevention. If NSAIDs stopped the development of Barrett's esophagus, the target group for treatment would be 40% of the population to decrease a fraction of the 10,000 esophageal adenocarcinoma cases in the U.S. every year. Given that NSAIDs are not benign, it is unlikely that such an effort is either worthwhile or feasible. If, on the other hand, NSAIDs work after the development of Barrett's esophagus, we have a more reasonable strategy whereby we treat a much smaller group of patients at much higher risk to achieve chemoprevention.

This large pooled analysis of individual-level participant data from six case-control studies in BEACON offered several notable strengths. With almost 1500 cases of Barrett's esophagus, we had greater power to detect associations, if present, than in any of the previous single site studies. Furthermore, because we were able to evaluate NSAID exposure compared with a common reference group (non-regular use), we reduced the potential for exposure misclassification. While we observed moderate heterogeneity across studies, we found no evidence that any individual study was overly influential, thus providing additional robustness and confidence to our findings. Finally, the use of individual-level data, with variables standardized across studies, and the ability to control for a wide range of potential confounders collected consistently across the studies were additional strengths of this pooled analysis.

Our study also has a number of limitations. There was some variability among the exposure questions from different studies; in particular, the definition of regular use. We addressed the misclassification of exposure definition across the studies by using a standard definition for regular use as described in the Methods; in the one study that did not specify regular use (16), we reclassified participants accordingly. Because of the way in which the individual studies asked participants about medication use (e.g., “have you used NSAIDs at least weekly in the past year?”), we were unable to examine separately ‘no use’ versus ‘low use’ of NSAIDs. The individual study ORs may differ somewhat from the pooled ORs due to differences in confounding structure. For example, race was a strong confounder of the association between NSAID use and risk of Barrett's esophagus in KPNC (14). Here, we limited the analyses to non-Hispanic white study participants. Finally, most of the six studies included a mix of patients with newly diagnosed and prevalent diagnoses of Barrett's esophagus, which could have biased the results unpredictably.

In summary, this pooled analysis found no evidence for an inverse association between use of NSAIDs and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. Given the known inverse association between NSAIDs and the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma, and analogous to that observed for colon cancer and polyps whereby NSAID use may stop progression from pre-cancer to cancer, these findings support investigations into the use of these chemopreventive agents for decreasing the risk of neoplastic progression from Barrett's esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Supplementary Material

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

Epidemiological studies have consistently shown an inverse association between regular use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

However, it remains unclear whether use of NSAIDs is also inversely associated with the precursor lesion, Barrett's esophagus.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

Use of NSAIDs was not associated with a reduced risk of Barrett's esophagus.

The findings from this large pooled analysis suggest that the likely protective mechanism of NSAIDs on esophageal adenocarcinoma occurs after to the development of Barrett's esophagus.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health RO1 DK63616 (D.A.C.); 1R21DK077742 (N.J.S. and D.A.C.); K23DK59311 (N.J.S.); R03 DK75842 (N.J.S.); K23DK079291 (J.H.R.); R01 CA116845 (H.B.E-S.); K24-04-107 (H.B.E-S.); the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health (M.B.C.); an Ireland–Northern Ireland cooperation research project grant sponsored by the Northern Ireland Research and Development Office and the Health Research Board, Ireland (FINBAR) (L.J.M.: RES/1699/01N/S); the Study of Digestive Health, NCI RO1 CA 001833 (D.C.W.); the Study of Reflux Disease, NCI R01 CA72866 (T.L.V.), the Established Investigator Award in Cancer Prevention and Control, K05 CA124911 (T.L.V.), and the US Department of Veterans Affairs CSRD Merit I01-CX000899 (J.H.R.).

Footnotes

Specific author contributions: A.P.T. contributed to data analysis, interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript. J.L.S. and M.B.C. contributed to interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript. L.A.A., L.J.M., J.H.R., H.B.E-S., T.L.V., D.C.W., and D.A.C. designed, obtained funding and collected data from individual case-control studies, contributed to the concept of the consortium, interpretation of data and refinement of the manuscript. All authors approved the final draft submitted.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Aaron P. Thrift, Ph.D.

Potential competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vaughan TL, Fitzgerald RC. Precision prevention of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;12:243–8. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thrift AP, Whiteman DC. The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma continues to rise: analysis of period and birth cohort effects on recent trends. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:3155–62. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Sex and racial disparity in incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma: observations and explanations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:330–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liao LM, Vaughan TL, Corley DA, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use reduces risk of adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction in a pooled analysis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:442–52. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, et al. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1825–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conio M, Cameron AJ, Romero Y, et al. Secular trends in the epidemiology and outcome of Barrett's oesophagus in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gut. 2001;48:304–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook MB, Wild CP, Everett SM, et al. Risk of mortality and cancer incidence in Barrett's esophagus. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2090–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rana PS, Johnston DA. Incidence of adenocarcinoma and mortality in patients with Barrett's oesophagus diagnosed between 1976 and 1986: implications for endoscopic surveillance. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:28–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2050.2000.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solaymani-Dodaran M, Logan RF, West J, et al. Risk of oesophageal cancer in Barrett's oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1070–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.028076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spechler SJ, Robbins AH, Rubins HB, et al. Adenocarcinoma and Barrett's esophagus. An overrated risk? Gastroenterology. 1984;87:927–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Burgh A, Dees J, Hop WC, et al. Oesophageal cancer is an uncommon cause of death in patients with Barrett's oesophagus. Gut. 1996;39:5–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S, Zhang XQ, Ding XW, et al. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors use is associated with reduced risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett's esophagus: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2378–88. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson LA, Johnston BT, Watson RG, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the esophageal inflammation-metaplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4975–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider JL, Zhao WK, Corley DA. Aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:436–43. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3349-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omer ZB, Ananthakrishnan AN, Nattinger KJ, et al. Aspirin protects against Barrett's esophagus in a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:722–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thrift AP, Pandeya N, Smith KJ, et al. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of Barrett's oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1235–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khalaf N, Nguyen T, Ramsey D, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1832–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubenstein JH, Morgenstern H, Appelman H, et al. Prediction of Barrett's esophagus among men. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:353–62. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edelstein ZR, Farrow DC, Bronner MP, et al. Central adiposity and risk of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:403–11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E, Ioannidis JP. Sensitivity of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: proposed metrics and empirical evaluation. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:1148–57. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vane JR. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a mechanism of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nat New Biol. 1971;231:232–5. doi: 10.1038/newbio231232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whittle BJ, Higgs GA, Eakins KE, et al. Selective inhibition of prostaglandin production in inflammatory exudates and gastric mucosa. Nature. 1980;284:271–3. doi: 10.1038/284271a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris CD, Armstrong GR, Bigley G, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in the Barrett's metaplasiadysplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:990–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson KT, Fu S, Ramanujam KS, et al. Increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 in Barrett's esophagus and associated adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2929–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buttar NS, Wang KK, Anderson MA, et al. The effect of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition in Barrett's esophagus epithelium: an in vitro study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:422–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.6.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta RA, DuBois RN. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor therapy for the prevention of esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett's esophagus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:406–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.6.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das D, Ishaq S, Harrison R, et al. Management of Barrett's esophagus in the UK: overtreated and underbiopsied but improved by the introduction of a national randomized trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1079–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.