Abstract

Background

Prevalence studies report Taenia solium cysticercosis in pig and human populations in Uganda. However, the factors influencing occurrence in smallholder pig production systems are not well documented and little is known about farmers’ perceptions of T. solium cysticercosis or farmer practices that could reduce transmission.

Methods

To determine the risk factors, perceptions and practices regarding T. solium cysticercosis, a household survey using a semi-structured questionnaire was conducted in 1185 households in the rural and urban pig production systems in Masaka, Mukono and Kamuli Districts. Logistic regression was used to measure associations of risk factors with infection. Performance scores were calculated to summarise perceptions and practices of farmers regarding taeniosis, human cysticercosis and porcine cysticercosis as well as farmer behavior related to control or breaking transmission.

Results

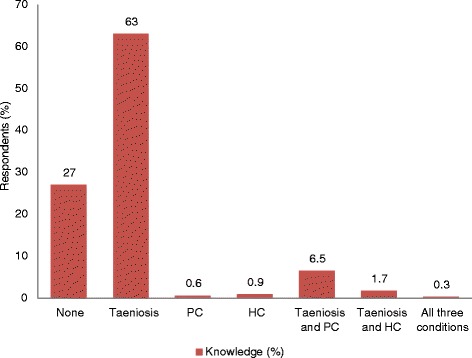

Pig breed type, farmers’ knowledge about transmission, sources of water used, and pig keeping homes where family members were unable to use the latrine were all significantly associated with T. solium cysticercosis in pigs. Performance scores indicated that farmers were more aware of taeniosis (63.0%; 95% Confidence Interval 60.0-65.8) than human or porcine cysticercosis; only three farmers (0.3%, 95% CI = 0.1–0.8) had knowledge on all three conditions. More farmers reported that they dewormed pigs (94.1%) than reported deworming themselves and their family members (62.0%). Albendazole was the most commonly used drug for deworming both pigs and humans (85.0 and 81.5% respectively). Just over half (54.6%) of the farmers interviewed had clean water near the latrines for washing hands. Of these, only 41.9% used water with soap to wash hands after latrine use.

Conclusion

Factors that significantly influenced occurrence of T. solium cysticercosis in pigs were identified. Farmers had some knowledge about the disease but did not link taeniosis, human cysticercosis, and porcine cysticercosis. Therefore, there is need to employ strategies that raise awareness and interrupt transmission.

Keywords: T. solium, Risk factors, Zoonosis, Perceptions, Pigs, Humans, Uganda

Background

Uganda is a developing country known to be endemic for Taenia solium cysticercosis, a public health challenge associated with poor pig-keeping practices and sanitation. The condition has a two-stage development cycle: the intermediate (larval) and the definitive (adult) stages. The intermediate stage occurs in pigs as the primary hosts causing porcine cysticercosis and in humans as accidental hosts resulting in human cysticercosis/neurocysticercosis [1, 2]. Humans harbor the final stage, a condition called taeniosis. Cases of pigs as secondary final hosts of this tapeworm infection have been described [3]. Neurocysticercosis, a life threatening form of human cysticercosis that occurs following invasion of the brain with metacestodes, has been reported to be the chief known cause of epilepsy in human populations in pig-keeping communities in the developing countries [4]. A recent study in Zambia indicated that up to 57% of epilepsy cases reported were attributed to neurocysticercosis [5, 6]. Although no such study has been done in Uganda to estimate prevalence of human cysticercosis/neurocysticercosis, presence of T. solium infection in pigs is a key indicator of the occurrence of the infection in the human population. Recent serological studies in Uganda have indicated that prevalence of porcine cysticercosis in pigs ranges between 8 and 12% [7, 8].

Various factors influencing the occurrence and spatial distribution of this condition in pigs and humans have been identified [9, 10]. Such factors include: poor hygiene and sanitation practices in humans, free-range pig rearing and tethering, lack of awareness about the disease and its transmission, poor or non-inspection of pigs before or following slaughter, use of contaminated water for pigs and people, and, eating under-cooked pork [11, 12].

Specifically, poor hygiene practices such as not washing hands with soap following visits to the latrines and before eating food, eating unwashed fruits and vegetables, and, drinking un-boiled or untreated water can lead to humans ingesting the eggs of T. solium [13]. Poor sanitation practices, such as open air defecation and latrines in poor conditions can allow pigs access to human feces [14]. Feces deposited in the open environment can be washed into unprotected springs and wells posing a risk to both pigs and humans [12, 15].

There are 3 main pig-rearing systems practiced in Uganda: free-range, tethered, and intensive confinement where pigs are kept in corrals with or without raised floors. The extensive production systems (free-range and tethered) are usually practiced during dry season when there is a scarcity of feed and agricultural activities, which pigs might disturb, are minimal [16, 17]. Extensive systems allow pigs access to human fecal material, thereby enabling the continuity of the T. solium lifecycle [13]. In northern Cameroon, where the free range pig management was estimated to be 90.7%, prevalence of the condition was high (26.6%) [10]. In Zambia, it was also reported that free-range management significantly influenced occurrence of the condition [18].

The disease has been shown to be prevalent in areas where inadequate or no inspection of pork is practiced [1, 18, 19]. This is the case in most communities in Uganda where pigs are slaughtered in un-gazetted areas and uninspected pork is then sold locally or transported to urban centres for marketing [20]. This poses a serious risk to pork consumers especially when they eat undercooked pork [14].

Community awareness of a disease is crucial for control and eventual eradication. Lack of knowledge about the pork tapeworm transmission cycle by farmers, consumers and non-consumers of pork, medical and veterinary personnel, policy makers and implementers in developing countries has made control of the potentially eradicable condition difficult [21]. Limited knowledge has been linked to increasing incidence among rural poor pig-keeping communities [12, 22–24].

Stakeholders in endemic areas may know about tapeworm infections in humans but may not relate it to porcine cysticercosis and neuro-cysticercosis [12]. In Uganda, misleading reports by the media which allege that “eating pork directly causes epilepsy” could complicate the control of T. solium infection [25]. Although change of behavior in communities is not automatic after acquisition of knowledge, it could be a key step in prevention of T. solium cysticercosis [12, 15, 23, 24].

Given the importance of pig rearing in Uganda and the high risk that consumption of poorly cooked pork represent for the communities, this study aimed to investigate risk factors, perceptions and practices of farmers regarding taeniosis and T. solium cysticercosis in order to inform future control initiatives of the disease.

Methods

Study design

The study was conducted from April to August 2013 in 22 villages of Masaka, Mukono and Kamuli districts in Uganda. Full details of selection criteria of study sites have been reported by Ouma et al. [26]. Description of study area, sample size calculation and sampling strategy were reported by Kungu et al. [7]. In short, districts were selected as being of high potential for smallholder pig systems. Power calculation indicated a minimum sample size of 384 pigs in each district. In each village, households were randomly selected from all pig-keeping households in each village. In selected households, one pig was randomly picked and blood collected. Serum harvested was then analyzed using the HP10Ag-ELISA [27] and B158C11A10/ B60H8A4 Ag-ELISA (apDIA Cysticercosis) [28]. Every sample that tested positive in either assays contributed to the overall estimated apparent sero-prevalence of the condition.

Household questionnaire

A questionnaire was administered to the owner of each pig that had been included in the survey to assess the risk factors for T. solium cysticercosis in the study sites. This questionnaire was adapted and modified from the Cysticercosis Working Group of East and Southern Africa (CWGESA) tool [29]. It was pre-tested by the first author on pig farmers in a non-study village (Mukono Municipality). It captured data on demographic characteristics, pig production and management, hygiene practices, knowledge and perceptions, as well as treatment of the condition in pigs and humans. Considering that many respondents were not fluent in English, four veterinary officers fluent in the commonly spoken indigenous language (Luganda in Masaka and Mukono, Lusoga in Kamuli) were used in each district as research assistants. Bleeding of pigs was concurrently done as already described by Kungu et al. [7]. Prior to the questionnaire administration, the study protocol was explained to the farmer and signed consent obtained.

Statistical analysis

Data from serology, household questionnaire was entered in Microsoft excel (2010) and exported to the STATA 11 software for analysis.

Analysis of risk factors

Descriptive statistics for the respondents and pig characteristics were determined. A univariable analysis using logistic regression was performed to determine associations between the risk factors and sero-prevalence of T. solium cysticercosis (Table 1). Factors with P-values ≤ 0.1 were included in a model for multivariable logistic step-wise regression analysis. A backward elimination procedure was used to exclude the factors one at a time, using P >0.05 as the criterion. Clustering was accounted for at two levels with district as a fixed variable and village as a random effect in the multivariable models. Model diagnostics were carried out by checking for normality of residuals at village level, as well as heteroscedasticity of residuals [30]. There was minimal variation between villages considering that village level residuals were all quite small (between −1 and +1). This was also shown by the small value for the village level variance in the final model. Therefore, the fixed effects had very little effect on the size of this variance, implying that even when they were removed from the model, variation between villages still remained limited. Tests for significance of associations and odds ratios were performed at Confidence Interval of 95% and significance level of 0.05.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondents in the three districts

| Characteristics | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent age-group | <20 years | 17 | 1.6 |

| 20–40years | 405 | 37 | |

| 41–60year | 507 | 46.3 | |

| >60 years | 167 | 15.2 | |

| Sex | Female | 351 | 32 |

| Male | 745 | 68 | |

| Religion | Christian | 1065 | 97.2 |

| Muslim | 4 | 0.4 | |

| SDA | 10 | 0.9 | |

| Traditional beliefs | 17 | 1.6 | |

| Ethnic grouping | Baganda | 670 | 61.1 |

| Basoga | 339 | 30.9 | |

| Banyankole | 15 | 1.4 | |

| Others | 72 | 6.6 | |

| Level of education | Never been | 114 | 10.4 |

| Primary | 550 | 50.2 | |

| Secondary | 349 | 31.8 | |

| Tertiary | 83 | 7.6 | |

| Primary activity | Livestock | 198 | 18.1 |

| Crop farming | 747 | 68.2 | |

| Civil service | 38 | 3.47 | |

| Business | 59 | 5.38 | |

| Others | 54 | 4.93 |

Analysis of perceptions and practices

Performance scores were calculated for each of the five different variables used to assess knowledge on taeniosis, porcine cysticercosis, and human cysticercosis as described by Dohoo [30]. Briefly, weights of 0–10 points were subjectively assigned as overall scores to the responses on questions assessing each knowledge variable. A respondent was considered to have knowledge on a variable when his/her responses scored 8–10 points and these were then recoded into dichotomous variables (has adequate knowledge versus does not have adequate knowledge). Descriptive statistics was used to generate proportions of responses on practices associated with control of T. solium cysticercosis.

Results

We sampled 375, 408, and 402 pigs in Masaka, Kamuli and Mukono, respectively. Only 1096 farmers of the 1185 whose pigs had been bled were interviewed. The remainder claimed to have commitments and left home immediately their pigs had been bled. Out of the 1185 pigs tested, 144 (12.2%) were positive by serology. Most respondents ranged from 20 to 60 years, and most were male (67.97%) and Christian by religion (97.2%). Details of the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents are in Table 1.

Determination of risk factors of T. solium cysticercosis

Several factors at the animal and household level were analyzed for their association with T. solium cysticercosis sero-prevalence in pigs. At animal level, six variables were assessed using univariable analysis. Only breed type had p-value ≤ 0.1 as indicated in Table 2. At the household level, 10 variables were assessed by univariable analysis. Level of education, knowledge of transmission cycle, water sources, and homes where people were unable to use latrine facilities had p-values ≤0.1 as shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Univariable analysis of risk factors for T. solium cysticercosis in pigs at animal level

| Factor | Number of pigs | Seropositive pigs (%) | p-value | Odds (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pig category | ||||

| Weanera | 455 | 60(13.2) | - | - |

| Gilt | 25 | 2(8) | 0.457 | 0.572 (0.132–2.490) |

| Castrate | 178 | 28(15.7) | 0.406 | 1.229 (0.756–1.999) |

| Boar | 177 | 17(9.6) | 0.218 | 0.699 (0.396–1.236) |

| Sow | 350 | 37(10.6) | 0.259 | 0.778 (0.503–1.203) |

| At least grazed on pasture | ||||

| Yes | 786 | 101(12.8) | 0.611 | 0.899 (0.597–1.355) |

| Noa | 299 | 35(11.7) | - | - |

| Husbandry systems | ||||

| Intensivea | 501 | 59(11.8) | - | - |

| Free range | 13 | 1(7.7) | 0.354 | 0.709 (0.342–1.469) |

| Tethering | 577 | 75(13) | 0.544 | 0.893 (0.621–1.286) |

| Breed type | ||||

| Locala | 195 | 26(13.3) | - | - |

| Cross | 733 | 104(14.2) | 0.005 | 2.659 (1.349–5.243) |

| Exotic | 256 | 14(5.5) | 0.000 | 2.858 (1.604–5.091) |

| Deworm pigs | ||||

| Yesa | 797 | 102(12.8) | - | - |

| No | 388 | 42(10.9) | 0.337 | 0.829 (0.566–1.215) |

| Source of pig | ||||

| Born on farma | 326 | 42(13.2) | - | - |

| Trader | 758 | 89(11.7) | 0.746 | 0.810 (0.227–2.898) |

| NGO/NAADS | 15 | 2(12.5) | 0.782 | 0.821 (0.119–5.675) |

| Gift | 62 | 7(11.3) | 0.591 | 0.710 (0.119–5.670) |

| Boar pay | 19 | 3(15.8) | 0.604 | 0.679 (0.157–2.930) |

aReference variable

Table 3.

Univariable analysis of risk factors for T. solium cysticercosis at household level

| Factor | Number of pigs | Seropositive pigs (%) | p-value | Odds (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of education | ||||

| None | 114 | 11(9.7) | 0.073 | 0.449(0.187–1.079) |

| Primary | 548 | 68(12.4) | 0.06 | 0.452(0.197–1.033) |

| Secondary | 348 | 40(11.5) | 0.089 | 0.593(0.325–1.083) |

| Tertiarya | 83 | 16(19.3) | - | - |

| Training in pig management | ||||

| Yesa | 488 | 62(12.7) | - | - |

| No | 603 | 73(12.1) | 0.397 | 0.728(0.348–1.52) |

| Water sources | ||||

| Unprotecteda | 419 | 37(8.8) | - | - |

| Protected | 677 | 98(14.5) | 0.008 | 0.583(0.391–0.870) |

| Boil water | ||||

| Alwaysa | 638 | 79(12.4) | - | - |

| Never | 453 | 56(12.4) | 0.992 | 1.002(0.695–1.444) |

| Eating pork | ||||

| At least once a month | 640 | 81(12.7) | 0.281 | 0.653(0.3–1.418) |

| After a month | 204 | 20(9.8) | 0.644 | 0.904(0.587–1.39) |

| Nevera | 246 | 34(13.8) | - | - |

| Slaughter at home | ||||

| Once a year | 101 | 8(16.5) | 0.200 | 0.629(0.31–1.278) |

| After a year | 21 | 4(19) | 0.157 | 0.583(0.276–1.231) |

| Nevera | 957 | 123(12.9) | - | - |

| Inspection on slaughter | ||||

| Alwaysa | 11 | 0 | - | - |

| Sometimes | 20 | 3(15) | 0.59 | 0.687(0.175–2.692) |

| Never | 111 | 12(10.8) | 0.999 | 0.000 |

| Presence of latrine | ||||

| No | 133 | 3(6) | 0.384 | 0.729(0.358–1.484) |

| Yesa | 1041 | 132(12.7) | - | - |

| Unable to use latrine | ||||

| Yes | 595 | 90(15.1) | 0.006 | 0.581(0.395–0.855) |

| Noa | 458 | 43(9.4) | - | - |

| Know transmission cycle | ||||

| Yes | 121 | 26(21.5) | 0.002 | 0.463(0.287–0.746) |

| Noa | 975 | 109(11.2) | - | - |

aReference variable

A multivariable logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of breed type, level of education, knowledge of transmission cycle, water sources, and being unable to use a latrine on the likelihood of pigs having T. solium cysticercosis (Table 4). Crossbred and exotic pigs were more likely to be positive than local pigs. Knowledge of the transmission cycle by farmers significantly was associated with a reduced likelihood of disease (0.476 times). Pigs from households that used water from protected sources (borehole, tap, tanks) were 0.525 times less likely to have the condition than those who used unprotected sources. Pigs in homes where all family members were able to use latrines were 0.576 times less likely to have disease.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis of animal and household level risk factors for T. solium cysticercosis

| Variable | B coefficient | P-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breed type | |||

| Local | Reference | ||

| Cross | 1.17 | 0.001 | 3.221 (1.599–6.488) |

| Exotic | 1.135 | 0.000 | 3.110 (1.733–5.580) |

| Level of education | |||

| None | Reference | ||

| Primary | −0.687 | 0.111 | 0.503 (0.216–1.172) |

| Secondary | −0.443 | 0.161 | 0.642 (0.345–1.194) |

| Tertiary | −0.542 | 0.104 | 0.582 (0.303–1.118) |

| Know transmission cycle | |||

| Yes | −0.743 | 0.003 | 0.476 (0.291–0.779) |

| No | Reference | ||

| Water source | |||

| Unprotected | Reference | ||

| Protected | −0.644 | 0.020 | 0.525 (0.350–0.787) |

| Unable to use latrine | |||

| Yes | Reference | ||

| No | −0.551 | 0.006 | 0.576 (0.389–0.853) |

Determination of perceptions and practices of farmers

Farmers’ perceptions of the three conditions

A knowledge performance score was conducted on the 1096 farmers’ responses related to taeniosis, human cysticercosis (HC) and porcine cysticercosis (PC) (Table 5). The proportions of the five different knowledge variables were calculated. Generally, farmers had highest knowledge on taeniosis (63.0%, 95% CI = 60.0-65.8) compared to other conditions. Only 3/1096 (0.3%, 95%CI = 0.1–0.8) respondents had knowledge about all three conditions as described in Fig. 1.

Table 5.

Proportions of the different variables used to assess level of knowledge on the infection

| Knowledge variable | Taeniosis, n (%) | Human cysticercosis, n (%) | Porcine cysticercosis, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How condition clinically manifests | 782 (71.4) | 56 (5.1) | 319 (29.1) |

| How condition is acquired | 780 (71.2) | 22 (2.0) | 127 (11.6) |

| Organs affected | 683 (62.4) | 32 (2.9) | 127 (11.6) |

| Effects of condition | 683 (62.4) | 56 (5.1) | 11 (1.0) |

| How to control condition | 658 (60) | 22 (2.0) | 38 (3.5) |

Fig. 1.

Responses (%) of farmers on knowledge of taeniosis, Porcine cysticercosis, Human cysticercosis

Male farmers had more knowledge about the three conditions than females. Farmers of Kamuli district, the most rural area of the study sites, had less knowledge about T. solium cysticercosis than Masaka and Mukono districts which are more urbanized. Table 6 shows the details of these findings.

Table 6.

Average proportions of knowledge of the condition by gender, level of education and districts

| Categories | Taeniosis (%) | Porcine cysticercosis (%) | Human cysticercosis (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 495/745 (66.4) | 107/745 (14.4) | 29/745 (3.9) |

| Female | 223/351 (63.5) | 18/351 (5.1) | 8/351 (2.2) |

| Level of education | |||

| None | 71/114 (62.3) | 18/114 (15.8) | 4/114 (3.5) |

| Primary | 344/550 (62.6) | 71/550 (12.9) | 19/550 (3.5) |

| Secondary | 224/349 (64.2) | 18/349 (5.2) | 12/349 (3.4) |

| Tertiary | 79/83 (95.2) | 18/83 (21.7) | 2/83 (2.4) |

| District | |||

| Kamuli | 160/400 (40.0) | 40/400 (10.0) | 6/400 (1.5) |

| Masaka | 259/324 (79.9) | 67/324 (20.7) | 16/324 (4.9) |

| Mukono | 293/372 (78.8) | 18/372 (4.8) | 15/372 (4.0) |

Control practices

Practices such as deworming of pigs and humans, as well as hand washing were assessed. More farmers reported that they dewormed pigs (94.1%) than reported deworming themselves and their family members (62.0%). Albendazole was the most commonly used drug for deworming both pigs and humans (85 and 81.5% respectively). Deworming practices varied significantly among the districts of Kamuli, Masaka and Mukono (Table 7). Just over half (54.6%) of the farmers interviewed had clean water near the latrines for washing hands. Of these, only 41.9% used water with soap to wash hands after latrine use. Availability of both water and soap varied significantly among the three districts (X 2 = 16.944, P < 0.05) (Table 8).

Table 7.

Proportions of responses on deworming practices associated with control of T. solium cysticercosis

| Deworming practice | Kamuli | Masaka | Mukono | Total, n (%) | X 2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deworming pigs | 4.295 | 0.000 | ||||

| Yes | 303 | 357 | 371 | 1031 (94.1) | ||

| No | 39 | 18 | 8 | 65 (6.3) | ||

| Deworm pigs how often | 3.495 | 0.000 | ||||

| 3 months interval | 94 | 178 | 216 | 488 (44.5) | ||

| Once a month | 131 | 110 | 93 | 334 (30.5) | ||

| > 3 months interval | 84 | 64 | 61 | 209 (25.0) | ||

| Drugs used | ||||||

| Albendazole | 122 | 229 | 209 | 932 (85.0) | ||

| Ivermectin | 33 | 23 | 108 | 164 (15.0) | ||

| Deworming self and family | 4.97 | 0.000 | ||||

| Yes | 143 | 244 | 293 | 680 (62.0) | ||

| No | 197 | 129 | 90 | 416 (38.0) | ||

| How often | 2.338 | 0.000 | ||||

| Once a month | 44 | 50 | 20 | 114 (16.8) | ||

| 3 months interval | 42 | 117 | 167 | 326 (47.9) | ||

| > 3 months | 57 | 77 | 106 | 240 (35.3) | ||

| Drugs used | 2.492 | 0.000 | ||||

| Albendazole | 122 | 228 | 204 | 554 (81.5) | ||

| Ivermectin | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.15) | ||

| Praziquantel | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 (0.74) | ||

| Others | 23 | 13 | 84 | 120 (17.7) |

Table 8.

Proportions of responses on hand washing practices associated with control of taeniosis-T. solium cysticercosis

| Practice | Masaka | Mukono | Kamuli | Total, n (%) | X 2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice hand washing | 0.698 | 0.706 | ||||

| Yes | 203 | 201 | 194 | 598 (54.6) | ||

| No | 185 | 163 | 150 | 498 (45.4) | ||

| Presence of clean water and soap | 16.944 | 0.00 | ||||

| Both present | 172 | 174 | 113 | 459 (76.8) | ||

| Only water present | 217 | 200 | 220 | 139 (23.2) |

Discussion

Although various factors expected to influence the transmission pattern of T. solium cysticercosis were assessed, only breed type, knowledge of the transmission cycle, use of water from protected sources, households with members unable to use latrines were found to be significant. We found that the odds of exotic and crossed pigs having T. solium cysticercosis infection were significantly higher than local ones. Similarly, Krecek et al. in South Africa reported a significantly higher sero-prevalence among crossbred pigs [31]. The pig breed types referred to here as ‘local’ have been reared for decades in the communities and are characterized by slow growth but they have adapted to the harsh conditions over time and are considered more resilient to diseases than recently introduced breeds or their crosses [32]. Also, there are some systematic differences in the way local pigs are kept and this may have influenced exposure or susceptibility. Sero-prevalence of T. solium cysticercosis in pigs was significantly less in homes that used protected water sources. A study in Mexico found that use of stagnant water in pigs significantly increased the prevalence in pigs [33]. Likewise, studies in Tanzania and Rwanda reported use of water from unprotected sources as an etiological factor for the condition [14, 34]. When contamination of the environment with T. solium eggs occurs, then the possibility for pigs and humans ingesting them is high when water from open sources such as rivers, streams, wells, and lakes is used in the homes without boiling or using decontaminating chemicals like chlorine [33]. Again confounding is possible, as households not using protected water sources are likely to differ consistently from those that do, and some of these differences could also affect pig exposure or susceptibility.

In our study, some household had latrines which some family members were not able to use. This was associated with a significant increase in porcine cysticercosis sero-prevalence. Children under age of 5 years, and weak, less mobile people (the old and sick) tend to carelessly defecate thereby increasing the risk of environmental contamination with the T. solium eggs. Thys et al. [12] reported that latrine use was influenced by taboos and socio-cultural beliefs thereby encouraging open-air defecation and eventual contamination of the environment with the T. solium eggs.

Community awareness about a disease is important for its control [35]. Our study associated knowledge of the transmission cycle by farmers with reduced likelihood of T. solium cysticercosis in pigs. Likewise, a study in Tanzania demonstrated that sensitization of pig keeping communities resulted in a significant reduction of the condition in pigs [21]. This study indicated that awareness of taeniosis was high among farmers compared to knowledge of human cysticercosis and porcine cysticercosis. Lack of knowledge of the latter conditions could hinder efforts of controlling the most preventable cause of epilepsy in the sub-Saharan African region [36]. Male farmers had more knowledge about the three conditions compared to female. This could be attributed to the more exposure men have at social gatherings than the women who are mostly involved in domestic work [20].

Many farmers routinely dewormed themselves and their pigs using albendazole. This practice would help limit transmission. According to the farmers, the practice was being implemented not because of their awareness about the specific dangers of T. solium cysticercosis but as a way of controlling worm infestations that were believed to hinder growth of the pigs and cause humans to get hungry shortly after a meal [37].

In our survey, just over half the farmers reported hand washing, similar to a nationwide survey which reports around one third of people practice hand washing (32.7%) [38]. Moreover, effectiveness of hand washing would be reduced by the low use of soap. Hand washing with soap, latrine use, and safe water use are considered by the World Health Organization as the key hygiene behaviors that limit the burden of infectious conditions like taeniosis-T. solium cysticercosis [39].

Conclusion

This study indicates that a number of factors associated with etiology and persistence of T. solium cysticercosis exist in pig production systems in Uganda. Special considerations should be giving to making latrines accessible to children, old people and people with disabilities. Use of water from protected sources should be encouraged. Programs of sensitization about the pig tapeworm and its public health importance could raise awareness. Appropriate health education of local communities on the transmission cycle of this condition might enhance good practices such as proper hygiene and sanitation, use of water from protected sources, boiling of drinking water.

A holistic approach drawing together veterinary, medical, and public health professionals involved in activities to control taeniosis-T. solium conditions should be envisaged to make such efforts cheaper yet more effective.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Smallholder Pig Value Chain Development (SPVCD) project funded by International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) to the CGIAR CRP3.7 Livestock and Fish through the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), and the German Academic Exchange Services (DAAD) for their financial support. We also thank pig farmers for Masaka, Mukono and Kamuli districts who willingly offered their valuable time to participate in this study, as well as all stakeholders and partners including District Veterinary Officers and Volunteer Efforts for Development Concerns (VEDCO) in Kamuli.

Availability of data and materials

Data has been submitted to this journal as additional supporting file.

Authors’ contributions

JMK: Conception and design of study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of manuscript, gave final approval for submission of manuscript. MMD: Design of study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of manuscript, gave final approval for submission of manuscript. FE: Conception and design of study, drafting and critical review of manuscript, gave final approval for submission of manuscript. MO: Conception and design of study, drafting and critical review of manuscript, gave final approval for submission of manuscript. DG: Conception of study, drafting and critical review of manuscript, gave final approval for submission of manuscript.

Authors’ information

JMK: Holds a PhD in Veterinary Epidemiology and works as a researcher of Animal Health at the National Livestock Resources Research Institute, Tororo, Uganda.

MMD: Holds a PhD in Veterinary Epidemiology and works as an Animal Health Scientist at International Livestock Research Institute, Kampala Uganda.

FE: Holds a PhD in Food safety and heads the Department of Veterinary Medicine Ecosystems and Biosecurity, College of Veterinary Medicine Animal Resources and Biosecurity Makerere University.

MO: Holds a PhD in Veterinary Medicine and heads the Department of Wildlife Animal Resources Management, College of Veterinary Medicine Animal Resources and Biosecurity Makerere University.

DG: Holds a PhD and heads the Food safety and Zoonoses program at International Livestock Resources Research Institute, Nairobi Kenya.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable in this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval of study was sought from the Research and Ethics Committee of the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biosciences of Makerere University (Reference number: VAB/REC/13/104) and the Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology (Reference number: HS1477). Prior to the interview, the objectives of the study were explained to each respondent and signed consent was obtained.

Abbreviation

- CI

Confidence interval

Contributor Information

Joseph M. Kungu, Phone: +256 78204 3931, Email: kungu@live.com

Michel M. Dione, Email: m.dione@cgiar.org

Francis Ejobi, Email: ejobifrancis@gmail.com.

Michael Ocaido, Email: mocaido@vetmed.mak.ac.ug.

Delia Grace, Email: d.grace@cgiar.org.

References

- 1.Sikasunge C, Siziya S, Vercruysse J, Phiri IK, Dorny P, Gabriel S, Willingham AL. Assessment of routine inspection methods for porcine cysticercosis in Zambian village pigs. J Helminthol. 2006;80(1):69–72. doi: 10.1079/JOH2005314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Neglected tropical diseases: cysticercosis-taeniosis. 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs376/en/. Accessed 16 Oct 2014.

- 3.Nakaya K, Craig PS, Margono SS. Dogs as alternative intermediate hosts of Taenia solium in Papua (Irian Jaya), Indonesia confirmed by highly specific ELISA and immunoblot using native and recombinant antigens and mitochondrial DNA analysis. J Helminthol. 2002;76:311–4. doi: 10.1079/JOH2002128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pondja A, Neves L, Mlangwa J, Afonso S, Fafetine J, Willingham AL, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of porcine cysticercosis in Angónia District, Mozambique. Flisser A, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(2):5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mwape KE, Phiri IK, Praet N, Speybroeck N, Muma JB, Dorny P, et al. The incidence of human cysticercosis in a Rural Community of Eastern Zambia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mwape KE, Blocher J, Wiefek J, Schmidt K, Dorny P, Praet N, et al. Prevalence of neurocysticercosis in people with epilepsy in the Eastern province of Zambia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(8):1–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kungu JM, Dione MM, Ejobi F, Harrison LJS, Poole EJ, Pezo D, et al. Seroprevalence of Taenia species in rural and urban smallholder pig production settings in Uganda. Acta Trop. 2016;1–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Nsadha Z, Thomas LF, Fèvre EM, Nasinyama G, Ojok L. Prevalence of porcine cysticercosis in the Lake Kyoga Basin, Uganda. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:239. doi:10.1186/s12917-014-0239-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Venkata RM, Jayaraman T, Muliyila J, Oommenb A, Dorny P, Vercruysse J, Rajshekhar V. Prevalence of porcine cysticercosis in Vellore, South India. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;107:67–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Assana E, Amadou F, Thys E, Lightowlers MW, Zoli AP, Dorny P, et al. Pig-farming systems and porcine cysticercosis in the north of Cameroon. J Helminthol. 2010;84(4):441–6. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X10000167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sikasunge CS, Phiri IK, Phiri AM, Dorny P, Siziya S, Willingham AL. Risk factors associated with porcine cysticercosis in selected districts of Eastern and Southern provinces of Zambia. Vet Parasitol. 2007;143(1):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thys S, Mwape KE, Lefèvre P, Dorny P, Marcotty T, Phiri AM, et al. Why latrines are not used: communities??? Perceptions and practices regarding latrines in a Taenia solium endemic rural area in Eastern Zambia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(3):1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mwape KE, Phiri IK, Praet N, Muma JB, Zulu G, van den Bossche P, et al. Taenia solium infections in a rural area of Eastern Zambia-A community based study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mwanjali G, Kihamia C, Kakoko DVC, Lekule F, Ngowi H, Johansen MV, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with human Taenia solium infections in Mbozi District, Mbeya Region, Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet] 2013;7(3):e2102. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulaya C, Mwape KE, Michelo C, Sikasunge CS, Makungu C, Gabriel S, et al. Preliminary evaluation of community-led total sanitation for the control of Taenia solium cysticercosis in Katete District of Zambia. Vet Parasitol. 2015;207(3–4):241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dione MM, Ouma EA, Roesel K, Kungu J, Lule P, Pezo D. Participatory assessment of animal health and husbandry practices in smallholder pig production systems in three high poverty districts in Uganda. Prev Vet Med. 2014;117(3–4):565–76. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muhanguzi D, Lutwama V, Mwiine FN. Factors that influence pig production in Central Uganda - Case study of Nangabo Sub-County, Wakiso district. Vet World. 2012;5(6):346–51. doi: 10.5455/vetworld.2012.346-351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sikasunge CS, Johansen MV, Willingham AL, Leifsson PS, Phiri IK. Taenia solium porcine cysticercosis: viability of cysticerci and persistency of antibodies and cysticercal antigens after treatment with oxfendazole. Vet Parasitol. 2008;158(1–2):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phiri IK, Dorny P, Gabriel S, Willingham AL, Speybroeck N, Vercruysse J. The prevalence of porcine cysticercosis in Eastern and Southern provinces of Zambia. Vet Parasitol. 2002;108(1):31–9. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ouma E, Dione M, Lule P, Roesel K, Pezo D. Characterization of smallholder pig production systems in Uganda: constraints and opportunities for engaging with market systems. Livest Res Rural Dev. 2014;26:3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ngowi HA, Carabin H, Kassuku AA, Mlozi MRS, Mlangwa JED, Willingham AL. A health-education intervention trial to reduce porcine cysticercosis in Mbulu District, Tanzania. Prev Vet Med. 2008;85(1–2):52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawlowski Z. Taeniosis/Neurocysticercosis control as a medical problem—A discussion paper. World J Neurosci. 2016;6(6):165–70. doi: 10.4236/wjns.2016.62020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabriël S, Dorny P, Mwape KE, Trevisan C, Braae UC, Magnussen P, et al. Control of Taenia solium taeniasis/cysticercosis: The best way forward for sub-Saharan Africa? Acta Trop. 2015; doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Thys S, Mwape KE, Lefèvre P, Dorny P, Phiri AM, Marcotty T, Phiri IK, Gabriël S. Why pigs are free-roaming: Communities’ perceptions, knowledge and practices regarding pig management and taeniosis/cysticercosis in a Taenia solium endemic rural area in Eastern Zambiatle. Vet Parasitol. 2016;225:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newvision. Epilepsy, the cause for worry to pork consumers in Kampala. Newvision online. 2014. http://www.newvision.co.ug/. Accessed 23 Apr 2014.

- 26.Ouma E, Dione M, Lule P, Pezo D, Marshall K, Roesel K, Mayega L, Kiryabwire D, Nadiope G, Jagwe J. ILRI (Research Report) Nairobi: ILRI; 2014. Smallholder pig value chain assessment in Uganda : results from producer focus group discussions and key informant interviews. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leslie HJ, Joshua GW, Wright SH, Parkhouse R. Specific detection of circulating surface/secreted glycoproteins of viable cysticerci in Taenia saginata cysticercosis. Parasite Immunol. 1989;11:351–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1989.tb00673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ApDia n.v . In vitro diagnostic kit Cysticercosis Ag ELISA. 2004. pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.CWGESA. The cysticercosis working group in Eastern and Subsaharan Africa. 2009. https://www.onehealthcommission.org/en/one_health_resources/whos_who_in_one_health/cysticercosis_working_group_cwgesa/.

- 30.Dohoo I, Martin W, Stryhn H. Veterinary epidemiologic research. 2. 2009. pp. 102–3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krecek RC, Mohammed H, Michael LM, Schantz PM, Ntanjana L, Morey L, et al. Risk factors of porcine cysticercosis in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.FAO . Pig Sector Kenya. FAO Animal Production and Health Livestock Country Reviews. No.3. Rome. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morales J, Martínez JJ, Rosetti M, Fleury A, Maza V, Hernandez M, Villalobos N, Fragoso G, Aluja A, Larralde C, Sciutto E. Spatial Distribution of Taenia solium Porcine Cysticercosis within a Rural Area of Mexico. Seto E, editor. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(9):7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rottbeck R, Nshimiyimana JF, Tugirimana P, Düll UE, Sattler J, Hategekimana J-C, et al. High prevalence of cysticercosis in people with epilepsy in southern Rwanda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(11):e2558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murrell KD, Dorny P, Flisser A, Geerts S, Kyvsgaard NC, Mcmanus DP, et al. WHO / FAO / OIE Guidelines for the surveillance, prevention and control of taeniosis / cysticercosis. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Willingham AL, Mugarura A. Taenia solium tapeworms and epilepsy in Uganda. Int Epilepsy News. 2008. pp. 10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolaczinski JH, Onapa AW, Ndyomugyenyi R, Brooker S. Neglected tropical diseases and their control in Uganda. Uganda: Situational analysis and needs assessment for the Malaria Consortium; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Republic of Uganda Ministry of Water and Environment. Sector performance report. 2014. www.mwe.go.ug/. Accessed 15 June 2015.

- 39.Aiello AE, Larson EL. What is the evidence for a causal link between hygiene and infections? Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:103–10. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data has been submitted to this journal as additional supporting file.