Abstract

Aim of this commentary is to report the most recent views about natural history of subclinical hypothyroidism (SH) according to the different etiologies. In children with idiopathic SH the natural evolution is often favourable, with a high percentage of cases reverting to euthyroidism or remaining SH even after a prolonged follow-up. By contrast, the risk of a significant deterioration of thyroid status is distinctly higher in the SH children with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT). This risk is even higher in the cases with both HT-related SH and chromosomal abnormalities, such as Turner or Down’s syndrome.

Keywords: Chromosomopathies, Down’s syndrome, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Thyroid function, Thyroid status, Turner syndrome

Background

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SH) is a biochemical condition characterized by serum TSH concentrations above the upper limit of the reference range and serum FT4 levels within the reference range [1]. Although its prevalence is generally reported to be higher in the elderly population, this condition may be quite common even in children and adolescents and pediatric endocrinologists frequently face the decision of what to do regarding SH children [2].

Data concerning the natural course of this condition in pediatric patients are controversial, probably due to the fact that it may be significantly conditioned by the different etiologies. SH, in fact, may be possibly caused by the same thyroid diseases which result in overt thyroid function impairment and, particularly, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT) [3, 4]. However, in most cases no definite etiology can be detected (idiopathic SH).

The aims of this commentary are to summarize the most recent views about natural evolution of SH in childhood and to analyze the most important predictive factors for its progression over time.

Predictive factors for SH progression

The natural history of SH may be the reversion to euthyroidism or the persistence over time or the progression to frank hypothyroidism (with reduced FT4 levels).

In adults the risk of a progression toward overt hypothyroidism seems to be higher [5, 6] than that generally reported in children and adolescents [7–12]. In fact, in most of the available pediatric studies the rate of development of a frank hypothyroidism ranges between 0 and 28.8%, whereas the majority of initially SH patients revert to euthyroidism or remain SH [13]. The initial presence of goiter and elevated thyroglobulin autoantibodies, the coexistence of celiac disease and a progressive increase in the serum values of thyro-peroxidase autoantibodies and TSH may be predictive of evolution toward thyroid failure [12, 14].

However, from the analysis of pediatric literature, it emerges that baseline TSH levels are probably the most powerful predictors of SH evolution over time [10, 15]. In fact, children with high baseline TSH concentrations are likely to need supranormal amounts of TSH to adequately stimulate the thyroid and, therefore, the persistence over time of a SH status is not surprising in these children [10, 15].

Other factors which can play a significant role in conditioning the natural course of SH in children seem to be the etiology (either idiopathic or secondary to HT or obesity) and a possible association with either Turner syndrome (TS) or Down’s syndrome (DS), i.e., two chromosomopathies that are known to be linked with an increased risk of autoimmune thyroid diseases (AITDs) [16].

Natural course of idiopathic SH

Pediatric studies on long-term evolution of SH in individuals with no apparent underlying thyroid disorders are few [10, 11, 17, 18].

In the retrospective and large study by Lazar et al. [10], TSH values during a 5-year follow-up tended to normalize over time, proportionally to the degree of TSH elevation at the onset of investigation. Predictive factors for a deterioration over time of thyroid function tests were an initial TSH value > 7.5 mIU/l and female gender, whilst age was not found to play a predictive role [10].

In the prospective multicenter study by Wasniewska et al. [11], based on a 2-year follow-up, 41.3% of the initially SH children normalized their TSH over time, whereas 58.7% remained SH and 12% increased TSH to >10 mIU/l. None of these children showed any symptoms of hypothyroidism during follow-up [11].

In the prospective study by Cerbone et al. [17], no alterations in growth, bone maturation, body mass index status and cognitive functions were observed, during a period of 2.0–9.3 years, in a series of children with idiopathic SH. These findings suggest that thyroid hormones involved in growth and neurocognitive development seem to be able to work properly, regardless of the persistently elevated TSH [2].

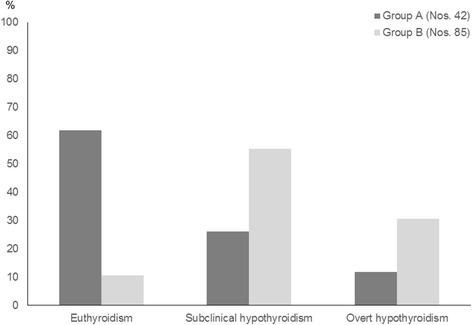

Finally, also the results of another five-year prospective study confirm that the natural history of idiopathic SH in pediatric age is characterized by a favourable long-term prognosis [18]. In fact, the majority of children with idiopathic SH (61.9%) spontaneously normalized over time their TSH values and only a minority (11.9%) became overtly hypothyroid at the end of follow-up (Fig. 1). By contrast, only a small minority (10.6%) of the patients who had presented with HT-related SH spontaneously normalized their TSH at the end of follow-up, whilst the majority remained SH or developed an overt hypothyroidism. On overall, these results confirm, on the basis of a prolonged prospective examination [18], the recent inference that underlying HT negatively affects the natural evolution of SH in children, irrespective of other concomitant risk factors [14].

Fig. 1.

Prevalence (%) of the main biochemical pictures of thyroid function detected, at the end of a 5-year follow-up, in two groups of children who presented with either idiopathic subclinical hypothyroidism (SH) (Group A) or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT)-related SH (Group B) (according to the results of Reference 18 study)

As the majority of prospective pediatric studies demonstrate that idiopathic SH is often a remitting or self-limiting process, thyroid function monitoring in these children should not be performed too frequently: every 12 months, according to the recent guidelines of the European Thyroid Association [19].

A controversial issue in the management of children with idiopathic SH is whether these cases should be treated or not. The evidence for benefit of L-T4 supplementation is poor [15], although this does not necessarily imply lack of benefit [20]. If there is an underlying HT, treatment might be taken into consideration, since progression from SH to overt hypothyroidism is more likely in these cases [12, 14, 18].

Natural course of HT- related SH

Thyroid function at HT presentation may significantly vary in the different pediatric cohorts [8, 9, 21–23]. In children euthyroidism is the most frequent presenting pattern, followed by SH and overt hypothyroidism [24]. Further and less frequent complaints of thyroid function which may be observed in children, at HT presentation, include either overt or subclinical hyperthyroidism [25, 26].

Thyroid function at HT diagnosis is mainly conditioned by patients’ age, with an increased risk of thyroid dysfunctions in the youngest children [4, 24].

In children and adolescents with HT, also the evolution over time of thyroid status may be quite variable [7, 9, 22, 27, 28] and is significantly affected by TSH serum levels at the time of HT diagnosis [7, 15].

According to the results of a recent report, a trend toward a progressive deterioration of thyroid status may be observed both in the initially euthyroid children and in those presenting with SH, although it has to be underlined that thyroid status prognosis in children with HT is not necessarily unfavourable [29]. In fact, at the end of a 5-year follow-up, 57.1% of the patients who had presented with euthyroidism remained euthyroid and 40.6% of those who were initially SH spontaneously normalized their thyroid function [29]. The results of that study, however, suggest that the patients presenting with SH may be more incline to develop over time a severe thyroid dysfunction picture, if compared with those presenting with euthyroidism [29].

In the light of the results of these studies on the natural course of thyroid status in children with HT- related SH, it might be proposed that thyroid function monitoring in these cases should be more strict than in children with idiopathic SH: every 6 months [30].

In the cases exhibiting a deterioration over time of thyroid status the hypothesis of a supplementation with L-T4 could not be preliminarily excluded, particularly considering the encouraging data reported by Svensson et al. [31]. These authors, in fact, in their retrospective study on 42 Swedish children with HT-related SH, found a significant reduction in median thyroid volume following a 2-year treatment with L-T4 [31].

Natural course of HT-related SH in Turner syndrome (TS)

TS, that is one of the commonest chromosomal abnormalities, is known to be associated with an increased risk of developing AITDs and also celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, vitiligo and juvenile idiopathic arthritis [32–37].

In TS girls HT is by far the commonest autoimmune disease, with a relative prevalence which has been reported to be even more elevated than that generally reported in age-matched girls without TS [32, 34, 35]. Also the other one AITD, i.e., Graves’ disease (GD), has been reported to be distinctly more frequent in TS girls than in the pediatric general population [32, 38–40].

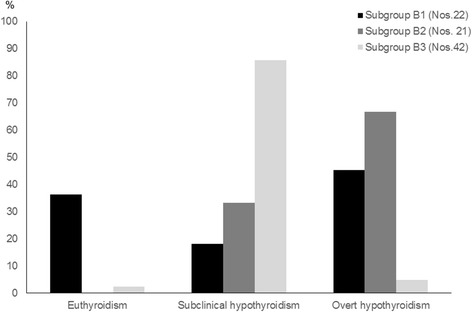

The spontaneous evolution over time of thyroid function tests in TS girls with HT seems to be characterized by a significant worsening of thyroid status, both in the children presenting with euthyroidism and in those presenting with SH [41]. This spontaneous trend is especially evident in the TS girls with initial SH and is irrespective of both karyotype and other factors [42]. This inference was, just recently, supported by a 5-year prospective study [18], which confirmed that the association with TS is able to affect the course of HT, by increasing the risk of a thyroid function deterioration over time [18]. According to the results of that study [18], in fact, none of TS girls with HT-related SH reverted to euthyroidism, at the end of follow-up and the majority progressed to overt hypothyroidism (Fig. 2). Such an evolution pattern was distinctly more severe when compared with that recorded in the children with HT-related SH but without TS (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Prevalence (%) of the main biochemical pictures of thyroid function detected, at the end of a 5-year follow-up, in three subgroups of children with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT)-related subclinical hypothyroidism without chromosomopathies (Subgroup B1) or with Turner syndrome (Subgroup B2) or Down’s syndrome (Subgroup B3) (according to the results of Reference 18 study)

To sum up, in the light of these peculiarities that characterize the natural course of TS-related HT, all individuals with TS should require continued monitoring of thyroid function throughout the life-span, as suggested by the TS Consensus Study Group [43].

Natural course of HT-related SH in Down’s syndrome (DS)

DS is another relatively common chromosomopathy, which is known to be associated with an increased prevalence of AITDs [16]. In fact, both HT and GD may be encountered relatively often in the clinical history of DS children, probably due to a dysregulation of immune system, with secondary impairment of inhibitory activity [44]. This hypothesis could explain the common link with other extra-thyroidal autoimmune disorders [45, 46], which may be found in around 65% of DS children [47]. Among these diseases, the one that is most typically associated with DS is alopecia [48].

SH is common in DS children and should not be necessarily interpreted as consequence of HT. In fact, it might also result from a congenital alteration in the regulation of thyroid function [47], which has been reported to be peculiar of DS [49, 50].

Natural evolution of HT-related SH in DS children has been, just recently, investigated by means of a 5-year follow-up study [18]. In the light of the results of that prospective study, the association with DS might be able to condition a peculiar biochemical course of HT [18]. In fact, if the thyroid function biochemical patterns at the end of follow-up were compared with the ones found in the same DS children 5 years earlier, the almost totality of patients maintained a SH picture and only a minority of them reverted to euthyroidism or progressed to overt hypothyroidism [Fig. 2]. It is also noteworthy that, in 7.1% of DS children with HT-related SH, HT switched over time to GD [18]. This is not surprising, considering that DS children might be prone to manifest over time a phenotypic metamorphosis from HT to GD and to subsequently fluctuate from hypothyroidism to hyperthyroidism [51].

Finally, a further phenotypical peculiarity of DS patients is that clinical expression of autoimmunity in these individuals may be particularly severe [52].

SH and obesity

Abnormalities of thyroid function are a frequent finding in obese children [53]. In particular, a SH may be encountered in 7.5% of these individuals [53]. The severity of SH in obese children is mainly conditioned by the level of overweight, whilst the distribution of patients with SH is not different between sexes and between prepubertal and pubertal individuals [53].

The pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for SH in obesity are not clear, although a role of leptin has been proposed [53]. In fact, serum leptin levels are increased in obese patients and some reports suggest that leptin can affect the hypothalamic regulation of TSH production [54]. However, since SH often reverts after weight loss, it seems to be a reversible complication of the overweight status and has not to be considered as a cause of obesity [53]. Therefore, any hormonal treatment should be avoided in obese children and also monitoring of thyroid function in these cases should not be too strict, since the risk of a progression toward overt hypothyroidism is not high. In fact, it has to be considered that FT3 serum levels are frequently increased in obese children, probably due to an adaptation process secondary to weight gain [53]. This should preserve obese children with SH from the risk of developing an overt hypothyroidism.

Conclusions

Long-term prognosis of mild and idiopathic SH is frequently benign. The evidence for benefit of L-T4 supplementation is poor, although this does not necessarily imply lack of benefit. If there is an underlying HT, thyroid function monitoring has to be more strict, since progression from SH to overt hypothyroidism is more likely in these cases.

The association with either TS or DS furtherly impairs the outcome of HT-related SH.

Acknowledgments

No Acknowledgments are provided.

Funding

No funding was necessary considering that the present one is a Commentary.

Authors’ contributions

(FDL and TA have organized the material and prepared its distribution in the different sections; MV and GS have written the paper; GZ has prepared the graphics; SS and DC have collected references). Each Author listed on the manuscript has seen and approved the submission of the present version of the manuscript and takes full responsibility for the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

The informed consent has been obtained from the parents of our patients.

Abbreviations

- AITDs

Autoimmune thyroid disorders

- DS

Down’s syndrome

- GD

Graves’ disease

- HT

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

- SH

Subclinical hypothyroidism

- TS

Turner syndrome

Contributor Information

Mariella Valenzise, Email: mvalenzise@unime.it.

Tommaso Aversa, Email: taversa@unime.it.

Giuseppina Zirilli, Email: zirillig@gmail.com.

Giuseppina Salzano, Email: gsalzano@unime.it.

Domenico Corica, Email: coricadomenico@hotmail.com.

Simona Santucci, Email: simo.santucci@virgilio.it.

Filippo De Luca, Email: filippo.deluca@unime.it.

References

- 1.Cooper DS, Biondi B. Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9821):1142–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monzani A, Prodam F, Rapa A, Moia S, Agarla V, Bellone S, et al. Endocrine disorders in childhood and adolescence. Natural history of subclinical hypothyroidism in children and adolescents and potential effects of replacement therapy: a review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;168(1):R1–11. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrigo T, Wasniewska M, Crisafulli G, Lombardo F, Messina MF, Rulli I, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism: the state of the art. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31(1):79–84. doi: 10.1007/BF03345571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasniewska M, Corrias A, Salerno M, Mussa A, Capalbo D, Messina MF, et al. Thyroid function patterns at Hashimoto’s thyroiditis presentation in childhood and adolescence are mainly conditioned by patients’ age. Horm Res Paediatr. 2012;78(4):232–6. doi: 10.1159/000343815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcocci C, Vitti P, Cetani F, Catalano F, Concetti R, Pinchera A. Thyroid ultrasonography helps to identify patients with diffuse lymphocytic thyroiditis who are prone to develop hypothyroidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;72(1):209–13. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-1-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vanderpump MP, Tunbridge WM, French JM, Appleton D, Bates D, Clark F, et al. The incidence of thyroid disorders in the community: a twenty-year follow-up of the Whickham Survey. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1995;43(1):55–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb01894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radetti G, Gottardi E, Bona G, Corrias A, Salardi S. Loche S; Study Group for Thyroid Diseases of the Italian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes (SIEDP/ISPED). The natural history of euthyroid Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in children. J Pediatr. 2006;149(6):827–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gopalakrishnan S, Chugh PK, Chhillar M, Ambardar VK, Sahoo M, Sankar R. Goitrous autoimmune thyroiditis in a pediatric population: a longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):e670–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demirbilek H, Kandemir N, Gonc EN, Ozon A, Alikasifoglu A. Assessment of thyroid function during the long course of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in children and adolescents. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2009;71(3):451–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazar L, Frumkin RB, Battat E, Lebenthal Y, Phillip M, Meyerovitch J. Natural history of thyroid function tests over 5 years in a large pediatric cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(5):1678–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wasniewska M, Salerno M, Cassio A, Corrias A, Aversa T, Zirilli G, et al. Prospective evaluation of the natural course of idiopathic subclinical hypothyroidism in childhood and adolescence. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160(3):417–21. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radetti G, Maselli M, Buzi F, Corrias A, Mussa A, Cambiaso P, et al. The natural history of the normal/mild elevated TSH serum levels in children and adolescents with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and isolated hyperthyrotropinaemia: a 3-year follow-up. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2012;76(3):394–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monzani A, Prodam F, Bellone S, Bona G. Subclinical hypothyroidism.In Bona G, De Luca F, Monzani A (eds) Thyroid Diseases in Childhood: Recent Advances from Basis Science to Clinical Practice. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp 181–194.

- 14.Aversa T, Valenzise M, Corrias A, Salerno M, De Luca F, Mussa A, et al. Underlying Hashimoto’s thyroiditis negatively affects the evolution of subclinical hypothyroidism in children irrespective of other concomitant risk factors. Thyroid. 2015;25(2):183–7. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wasniewska M, Corrias A, Aversa T, Valenzise M, Mussa A, De Martino L, et al. Comparative evaluation of therapy with L-thyroxine versus no treatment in children with idiopathic and mild subclinical hypothyroidism. Horm Res Paediatr. 2012;77(6):376–81. doi: 10.1159/000339156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aversa T, Lombardo F, Valenzise M, Messina MF, Sferlazzas C, Salzano G, et al. Peculiarities of autoimmune thyroid diseases in children with Turner or Down syndrome: an overview. Ital J Pediatr. 2015;41:39. doi: 10.1186/s13052-015-0146-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerbone M, Bravaccio C, Capalbo D, Polizzi M, Wasniewska M, Cioffi D, et al. Linear growth and intellectual outcome in children with long-term idiopathic subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(4):591–7. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wasniewska M, Aversa T, Salerno M, Corrias A, Messina MF, Mussa A, et al. Five-year prospective evaluation of thyroid function in girls with subclinical mild hypothyroidism of different etiology. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(6):801–8. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarus J, Brown RS, Daumerie C, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Negro R, Vaidya B. 2014 European thyroid association guidelines for the management of subclinical hypothyroidism in pregnancy and in children. Eur Thyroid J. 2014;3(2):76–94. doi: 10.1159/000362597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Grady MJ, Cody D. Subclinical hypothyroidism in childhood. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(3):280–4. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.181800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zak T, Noczyńska A, Wasikowa R, Zaleska-Dorobisz U, Golenko A. Chronic autoimmune thyroid disease in children and adolescents in the years 1999–2004 in Lower Silesia, Poland. Hormones. 2005;4(1):45–8. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.11142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozen S, Berk Ö, Şimşek DG, Darcan S. Clinical course of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and effects of levothyroxine therapy on the clinical course of the disease in children and adolescents. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2011;3(4):192–7. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skarpa V, Kousta E, Tertipi A, Anyfandakis K, Vakaki M, Dolianiti M, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of children with autoimmune thyroid disease. Hormones (Athens) 2011;10(3):207–14. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Luca F, Aversa T, Salzano G, Zirilli G, Sferlazzas C, Wasniewska M. Autoimmune Thyroiditis. In: Bona G, De Luca F, Monzani A, editors. Thyroid Diseases in Childhood: Recent Advances from Basis Science to Clinical Practice. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. pp. 181–94. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wasniewska M, Corrias A, Salerno M, Lombardo F, Aversa T, Mussa A, et al. Outcomes of children with hashitoxicosis. Horm Res Paediatr. 2012;77(1):36–40. doi: 10.1159/000334640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aversa T, Valenzise M, Corrias A, Salerno M, Mussa A, Capalbo D, et al. Subclinical hyperthyroidism when presenting as initial manifestation of juvenile Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: first report on its natural history. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014;37(3):303–8. doi: 10.1007/s40618-014-0054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Vries L, Bulvik S, Phillip M. Chronic autoimmune thyroiditis in children and adolescents: at presentation and during long-term follow-up. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(1):33. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.134841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MW, Shin DY, Kim KJ, Hwang S, Lee EJ. The biochemical prognostic factors of subclinical hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Metab. 2014;29(2):154–62. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2014.29.2.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aversa T, Corrias A, Salerno M, Tessaris D, Di Mase R, Valenzise M et al. Five-Year Prospective Evaluation of Thyroid Function Test Evolution in Children with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Presenting with Either Euthyroidism or Subclinical Hypothyroidism. Thyroid. 2016.Sep 13 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Karmisholt J, Andersen S, Laurberg P. Variation in thyroid function in subclinical hypothyroidism: importance of clinical follow-up and therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(3):317–23. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svensson J, Ericsson UB, Nilsson P, Olsson C, Jonsson B, Lindberg B, et al. Levothyroxine treatment reduces thyroid size in children and adolescents with chronic autoimmune thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(5):1729–34. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livadas S, Xekouki P, Fouka F, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Kaloumenou I, Mavrou A, et al. Prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in Turner’s syndrome: a long-term follow-up study and brief literature review. Thyroid. 2005;15(9):1061–6. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakalov VK, Cheng C, Zhou J, Bondy CA. X-chromosome gene dosage and the risk of diabetes in Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(9):3289–96. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuda I, Hizuka N, Kurimoto M, Morita J, Tanaka S, Yamakado Y, et al. Autoimmune thyroid diseases in 65 Japanese women with Turner syndrome. Endocr J. 2009;56(8):983–6. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.K09E-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larizza D, Calcaterra V, Martinetti M. Autoimmune stigmata in Turner syndrome: when lacks an X chromosome. J Autoimmun. 2009;33(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jørgensen KT, Rostgaard K, Bache I, Biggar RJ, Nielsen NM, Tommerup N, et al. Autoimmune diseases in women with Turner’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(3):658–66. doi: 10.1002/art.27270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lleo A, Moroni L, Caliari L, Invernizzi P. Autoimmunity and Turner’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11(6–7):A538–43. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radetti G, Mazzanti L, Paganini C, Bernasconi S, Russo G, Rigon F, et al. Frequency, clinical and laboratory features of thyroiditis in girls with Turner’s syndrome. The Italian Study Group for Turner’s Syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84(8):909–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wasniewska M, Corrias A, Messina MF, Crisafulli G, Salzano G, Valenzise M, et al. Graves’ disease prevalence in a young population with Turner syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33(1):69–70. doi: 10.1007/BF03346552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valenzise M, Aversa T, Corrias A, Mazzanti L, Cappa M, Ubertini G, et al. Epidemiology, presentation and long-term evolution of Graves’ disease in children, adolescents and young adults with Turner syndrome. Horm Res Paediatr. 2014;81(4):245–50. doi: 10.1159/000357130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wasniewska M, Salerno M, Corrias A, Mazzanti L, Matarazzo P, Corica D et al.The Evolution of Thyroid Function after Presenting with Hashimoto Thyroiditis Is Different between Initially Euthyroid Girls with and Those without Turner Syndrome. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016 Nov 19. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Aversa T, Messina MF, Mazzanti L, Salerno M, Mussa A, Faienza MF, et al. The association with Turner syndrome significantly affects the course of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in children, irrespective of karyotype. Endocrine. 2015;50(3):777–82. doi: 10.1007/s12020-014-0513-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bondy CA, Turner Syndrome Study Group Care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: a guideline of the Turner Syndrome Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(1):10–25. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pellegrini FP, Marinoni M, Frangione V, Tedeschi A, Gandini V, Ciglia F, et al. Down syndrome, autoimmunity and T regulatory cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;169(3):238–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graber E, Chacko E, Regelmann MO, Costin G, Rapaport R. Down syndrome and thyroid function. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2012;41(4):735–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King K, O’Gorman C, Gallagher S. Thyroid dysfunction in children with Down syndrome: a literature review. Ir J Med Sci. 2014;183(1):1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-0994-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aversa T, Salerno M, Radetti G, Faienza MF, Iughetti L, Corrias A, et al. Peculiarities of presentation and evolution over time of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in children and adolescents with Down’s syndrome. Hormones (Athens) 2015;14(3):410–6. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aversa T, Valenzise M, Corrias A, Salerno M, Iughetti L, Tessaris D, et al. In children with autoimmune thyroid diseases the association with Down syndrome can modify the clustering of extra-thyroidal autoimmune disorders. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2016;29(9):1041–6. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2016-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Trotsenburg AS, Vulsma T, van Rozenburg-Marres SL, van Baar AL, Ridder JC, Heymans HS, et al. The effect of thyroxine treatment started in the neonatal period on development and growth of two-year-old Down syndrome children: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3304–11. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Claret C, Goday A, Benaiges D, Chillarón JJ, Flores JA, Hernandez E, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism in the first years of life in patients with Down syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2013;73(5):674–8. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aversa T, Valenzise M, Salerno M, Corrias A, Iughetti L, Radetti G, et al. Metamorphic thyroid autoimmunity in Down Syndrome: from Hashimoto’s thyroiditis to Graves’ disease and beyond. Ital J Pediatr. 2015;41:87. doi: 10.1186/s13052-015-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salzano G, Lombardo F, Arrigo T, Sferlazzas C, Wasniewska M, Valenzise M, et al. Association of five autoimmune diseases in a young woman with Down’s syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33(3):202–3. doi: 10.1007/BF03346582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marras V, Casini MR, Pilia S, Carta D, Civolani P, Porcu M, et al. Thyroid function in obese children and adolescents. Horm Res Paediatr. 2010;73(3):193–7. doi: 10.1159/000284361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Costa da Veiga MA, Oliveira Kde J, Curty FH, de Moura CC. Thyroid hormones modulate the endocrine and autocrine/paracrine actions of leptin on thyrotropin secretion. J Endocrinol. 2004;183(1):243–7. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.05746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]