Abstract

Introduction

Preoperative anaemia remains undertreated in the UK despite advice from national agencies to implement blood conservation measures. A local retrospective audit of 717 primary hip/knee replacements in 2008–2009 revealed 25% of patients were anaemic preoperatively. These patients experienced significantly increased transfusion requirements and length of stay. We report the results of a simple and pragmatic blood management protocol in a district general hospital.

Methods

Since 2010 patients at our institution who are found to be anaemic when listed for hip/knee replacement have been offered iron supplementation and/or erythropoietin depending on haemoglobin and ferritin levels. In this study, postoperative blood transfusions, length of stay and readmissions were assessed retrospectively for all patients undergoing elective primary hip/knee replacement in 2014 and compared with the baseline findings.

Results

During the 12-month study period, 406 patients were eligible for inclusion and none were excluded. Eighty-nine patients (22%) were anaemic preoperatively and sixty-five received treatment. The transfusion rate fell from the baseline levels of 23.0% and 6.7% to 4.3% and 0.5% for hip and knee replacements respectively (p<0.001). The median length of stay reduced from 6 to 3 days (p<0.001) for both hip and knee replacements. The rate for readmissions within 90 days fell from 13.5% to 8.9% (p<0.05).

Conclusions

Preoperative anaemia is common in patients listed for hip/knee replacement and it is associated strongly with increased blood transfusion. The introduction of a blood management protocol has led to significant reductions in transfusion and length of stay, sustained over a four-year period. This suggests that improved patient outcomes, conservation of blood stocks and cost savings can be achieved.

Keywords: Blood transfusion, Anaemia, Erythropoietin, Total hip replacement, Total knee replacement

Total hip and knee arthroplasty numbers are increasing steadily, with over 200,000 procedures performed in England and Wales in 2015.1 Total hip replacement (THR) alone accounts for approximately 5% of donated red cells transfused in the UK.2,3 Preoperative anaemia is common and leads to increased need for allogeneic blood transfusion (ABT) as well as increased length of stay (LOS) and morbidity4–6 after total hip and knee arthroplasty.

The NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) national comparative audit of blood use following elective THR highlighted wide variation in transfusion practice across England with ABT rates ranging from 10% to 90%.3 The NHSBT and the Department of Health advise that hospitals should have a written policy for identification and treatment of anaemia preoperatively as well as methods to optimise haemostasis.3,7 However, specific guidance is not given. We conducted a survey of hospitals in our region in March 2015 and found that only 2 of 11 trusts that responded (including our own) had such a policy in place. There has been growing interest in patient blood management over the past decade with several studies in the anaesthetic and transfusion journals. Despite this, there have been few publications in the surgical literature.

In 2010 a local retrospective audit was performed to assess prevalence of preoperative anaemia and establish baseline transfusion rates. Following this, a patient blood management protocol was implemented in our hospital with the aim of early identification and treatment of preoperative anaemia and minimising perioperative blood loss. These findings have been previously published.8 The purpose of this study was to reaudit four years later to assess the efficacy and cost effectiveness of the programme after the initiating clinician had left the trust and there had been a slight modification of the protocol. The primary outcome measure was proportion of patients receiving ABT. Secondary outcomes were LOS, readmission after discharge and the net cost of the programme.

Methods

The project was classified as audit by the National Research Ethics Service and the SQUIRE (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines were followed for reporting the project’s effects.9 Data security procedures were approved by the trust’s Caldicott guardian. Only elective primary hip and knee replacement procedures were included. Revision, resurfacing or acute procedures (eg following hip fracture) were not considered.

Airedale General Hospital performs 400–500 primary hip/knee replacements annually with a National Joint Registry reporting rate of >95%.1 Our ABT rate for THR in the 2007 NHSBT audit was 23% compared with the national average of 25%.3 Trust guidelines regarding postoperative blood loss advise transfusion to maintain a haemoglobin concentration of >7g/dl in otherwise fit patients, and >9g/dl in older patients and those with known cardiovascular disease. Thromboprophylaxis (dalteparin 5,000 units) and discharge criteria are the same for all patients. Tourniquet use for total knee replacement (TKR) is universal unless specific contraindications exist. Wound drains are not used routinely. Intraoperative cell salvage is routine for revision joint replacements but not for primary joint replacements. The above guidelines and practices have remained unaltered.

Baseline audit

All THRs and TKRs performed between January 2008 and December 2009 were identified retrospectively from the theatre database, and records were cross-referenced with patient administration, laboratory and transfusion databases. Revision procedures and THR for trauma were excluded. The following information was recorded: patient demographics (age, sex and ASA [American Society of Anesthesiologists] grade), preoperative haemoglobin (Hb) concentration, admission/discharge date, admitting consultant and operating surgeon. Postoperative outcome measures were: postoperative nadir Hb (lowest Hb between operation and discharge), number of units transfused, LOS and readmission (for any reason) within 90 days from discharge.

Multivariate regression analyses, using linear and logistic regression for continuous and binary data respectively, were used to evaluate the effect of operation (THR or TKR), sex, age, operating surgeon and preoperative Hb on transfusion rate, LOS and readmission. Analysis was performed using Stata® version 9.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, US).

Algorithm design and implementation

At the time of the baseline audit, there was no local guideline regarding management of anaemia preoperatively or for intraoperative blood conservation. In 2010 a blood management protocol was agreed after discussion of the baseline audit findings with the anaesthetic, orthopaedic and haematology departments, and reviewing the literature.10 At the same time, an enhanced recovery pathway was implemented, encompassing preoperative patient education and perioperative analgesia.

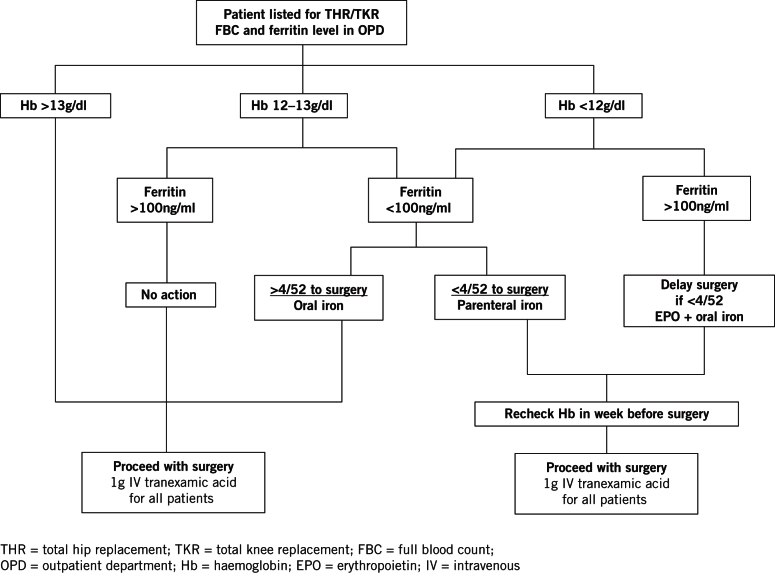

Figure 1 shows the algorithm used. Baseline blood tests are taken once a patient is listed for elective arthroplasty. Patients with Hb <13g/dl are referred to an anaesthetist (JH) to decide on treatment following review of the medical notes. The algorithm is not applied to patients under the care of a consultant haematologist and patients with features suspicious of occult malignancy are referred to their general practitioner (GP).

Figure 1.

The Airedale algorithm

If surgery is more than four weeks away and the patient’s ferritin is <100ng/ml, the patient’s GP is asked to prescribe oral iron. If surgery is less than four weeks away, intravenous iron (Ferinject®; Vifor Pharma, Bagshot, UK) is offered and administered as a day-case procedure. Patients with Hb <12g/dl and ferritin >100ng/ml are considered for erythropoietin (Eprex®; Janssen-Cilag, High Wycombe, UK) (EPO) on a case-by-case basis, given weekly for three weeks before surgery with a dose on admission. Medications are used within licence and dosed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Patients treated with parenteral iron or EPO have their Hb measured in the final week before surgery to assess their response.

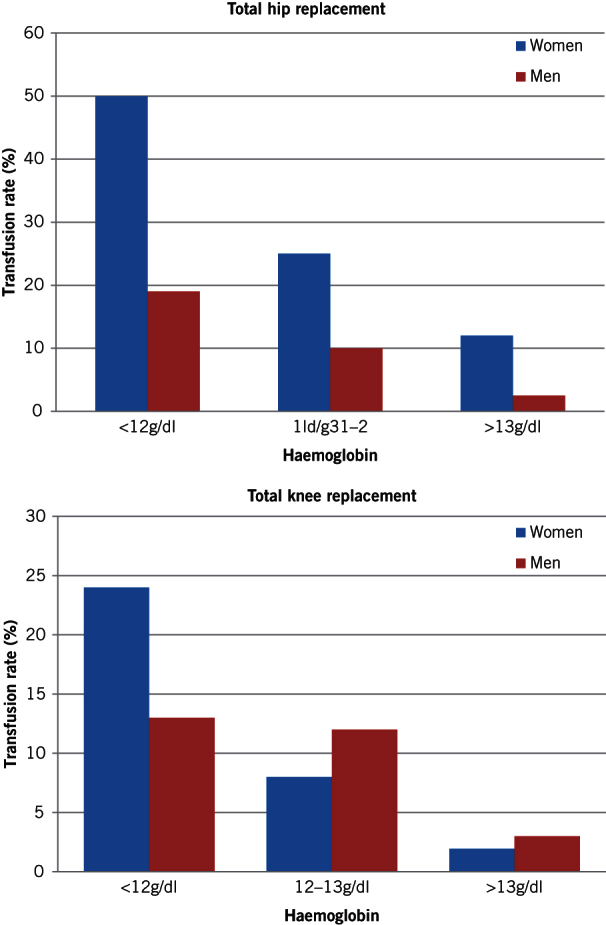

Following reaudit in 2010, vitamin B12 and folate measurements were no longer taken as these did not influence management. Contrary to other guidance,11–13 our management does not discriminate between the sexes. Since transfusion triggers are the same and women were shown to have a higher transfusion risk in our baseline audit, identical treatment thresholds were adopted for men and women. Accordingly, women with Hb 12–13g/dl and test results suggestive of functional iron deficiency are offered iron at the discretion of the anaesthetist.

Subsequent to the new algorithm being implemented, data for all primary THRs and TKRs performed between April and December 2010 were collected prospectively and compared against the retrospective controls on an intention-to-treat basis. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare binary outcomes. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess whether continuous data followed a Gaussian distribution. Mann–Whitney U and t-tests were used as appropriate. Statistical significance was assumed at a two-tailed p-value of <0.05.

Final follow-up audit

All primary elective THRs and TKRs performed between January and December 2014 were identified retrospectively from the theatre database. Data were collected and analysed as before.

Results

Baseline data

The full results of the baseline audit have been published previously.8 In summary, complete datasets were available for 333 THRs and 358 TKRs. The prevalence of preoperative anaemia (Hb <12g/dl in women and <13g/dl in men) was 24.6%. Preoperative anaemia and absolute preoperative Hb independently predicted ABT while controlling for age, sex, operation site and Hb loss. The odds ratio (OR) was 11.6 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.2–25.7; p<0.001) for anaemia as a binary variable (anaemic vs non-anaemic). For absolute Hb, the OR was 0.25 per 1g/dl increment (95% CI: 0.19–0.35; p<0.001). Figure 2 shows the relationship between preoperative haemoglobin and transfusion rate.

Figure 2.

Relationship between preoperative haemoglobin and transfusion rate

LOS was predicted by preoperative Hb (decrease in LOS by 0.70 days per 1g/dl increment in Hb, 95% CI: -0.09–-1.62 days; p<0.005) and patient age (increase in LOS by 0.13 days per 1-year increment in age, 95% CI: 0.07–0.19 days; p<0.001). ABT predicted all-cause hospital readmission within 90 days after discharge (OR: 2.94, 95% CI: 1.27–6.77; p=0.01).

The overall transfusion rates for THR and TKR were 23.0% and 6.7% respectively. The median LOS was 6 days (interquartile range: 5–8 days) for both procedures. The all-cause readmission rate within 90 days from discharge was 13.5% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of audit results

| 2009 Baseline | 2010 Reaudit | 2014 Final audit | |

| Female-to-male ratio | 412:305 | 155:126 | 223:183 |

| THR-to-TKR ratio | 361:356 | 158:123 | 186:220 |

| Median ASA grade | 2 (IQR: 2–2) | 2 (IQR: 2–3) | 2 (IQR: 2–3) |

| Median age in years | 72 (IQR: 65–78) | 74 (IQR: 66–80) | 71 (IQR: 65–77) |

| Preoperative anaemia | 170/691 (25%) | 73/281 (26%) | 89/406 (22%) |

| Hb <13g/dl | 276/691 (40%) | 87/281 (31%) | 160/406 (39%) |

| Median nadir Hb in transfused patients in g/dl | 7.8 (IQR: 7.2–8.7) | 7.6 (IQR: 7.3–9.2) | 8.2 (IQR: 7.7–8.7) |

| Median Hb loss for THR in g/dl | 3.8 (IQR: 2.9–4.9) | 3.1* (IQR: 1.9–4.6) | 2.2* (IQR: 1.5–2.9) |

| Median Hb loss for TKR in g/dl | 3.1 (IQR: 1.9–4.6) | 2.6** (IQR: 2.0–3.3) | 1.5* (IQR: 0.8–2.2) |

| Transfusion for THR | 83/361 (23.0%) | 12/158 (7.6%)* | 8/186 (4.3%)* |

| Transfusion for TKR | 24/356 (6.7%) | 0/123 (0%)* | 1/220 (0.5%)* |

| Total units transfused | 320 | 25 | 20 |

| Median length of stay for THR in days | 6 (IQR: 5–8) | 5* (IQR: 3–7) | 3* (IQR: 2–4) |

| Median length of stay for TKR in days | 6 (IQR: 5–8) | 4* (IQR: 3–6) | 3* (IQR: 3–5) |

| Readmitted within 90 days of discharge | 97/717 (13.5%) | 23/281 (8.2%)*** | 36/406 (8.9%)*** |

TKR = total knee replacement; THR = total hip replacement; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; IQR = interquartile range; Hb = haemoglobin

*p<0.001; **p<0.01; ***p<0.05

Initial reaudit in 2010

Data for 158 and 123 patients undergoing THR and TKR respectively were collected prospectively between April and December 2010. Seventy-three patients (26.0%) presented with anaemia preoperatively, reducing to twenty-nine (10.3%) after treatment (p<0.001). Thirty-one patients were treated with oral iron alone, thirteen received parenteral iron and twenty-two received EPO with oral iron.

Twenty-one patients went untreated. In 14 cases, this was for logistical reasons (eg anaesthetist involved in the development of the algorithm not available for consultation). The remaining five patients presented with Hb >12g/dl and had no evidence of iron deficiency; as per protocol, these patients were not offered treatment. The transfusion rate, LOS and readmission rate within 90 days were all significantly reduced (Table 1).

Final reaudit in 2014

During the 12-month final reaudit period, 406 patients (186 hips, 220 knees) were eligible to be included in analysis and none were excluded. A fifth of patients (n=89, 21.9%) were anaemic preoperatively and two-fifths (n=160, 39.4%) presented with Hb <13g/dl. Forty-eight patients were treated with oral iron alone, nine received parenteral iron and nine received EPO with oral iron.

Twenty-nine patients had Hb >12g/dl with ferritin >100ng/ml; as per protocol, these patients did not require treatment. In some circumstances, patients were managed on a case-by-case basis instead of following protocol. Eighteen patients had Hb >12g/dl with ferritin <100ng/ml but were not offered treatment. This was also the case for eight patients with Hb <12g/dl and ferritin <100ng/ml, and nine with Hb <12g/dl and ferritin >100ng/ml. Twenty patients attended preassessment when there was under two weeks to surgery and rather than postpone the operation, it was decided that they should proceed without treatment. Ferritin was not measured in nine cases.

The transfusion rates for THR and TKR were 4.3% and 0.5% respectively, significantly less than at baseline (p<0.001). The single patient transfused after TKR received four units following an upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage while the eight patients transfused following THR each received two units. The median LOS was significantly shorter at 3 days for both THR and TKR (p<0.001). The readmission rate rose slightly from the 2010 audit but remained significantly lower than baseline at 8.9% (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Cost analysis

Table 2 shows a breakdown of the costs involved using figures from our hospital pharmacy and blood bank. Total allogeneic blood use decreased from 320 units for 717 procedures at baseline to 20 units for 406 procedures in 2014. A group of 406 patients from the baseline group would have required 181 units (320/717 x 406). The cost saving on blood in 2014 was therefore calculated as £23,345. This is a conservative figure as it only takes into account the acquisition and cross-match costs. Total activity-based costs are estimated to be at least three times higher.14 The drug costs of running the programme are offset easily by transfusion savings, even using the most conservative estimates, and all these sums are small compared with the savings from reduced bed occupancy.

Table 2.

Cost analysis

| Cost | ||

| 1g intravenous iron | (9 x 4 doses) x £181.45 | £6,532 |

| 20,000 units erythropoietin | (9 x 4 doses) x £27.80 | £1,001 |

| 1g intravenous tranexamic acid | 406 doses x £1.30 | £528 |

| Ferrous sulphate | 48 x £4.36 (2-month supply) | £209 |

| Units of blood saved | (181–20) x £145.00 | -£23,345 |

| Bed days saved | (406 x 3) x £400.00 | -£487,200 |

| Total | -£502,455 |

Discussion

This paper reports the results of a quality improvement cycle, describing the design and implementation of a patient blood management programme in response to a combination of local data, national guidelines and international opinion. Our approach to optimising preoperative Hb levels and limiting blood loss intraoperatively has led to significantly lower ABT rates, a shorter LOS and a reduction in readmissions after elective primary hip/knee arthroplasty.

The relationships between anaemia and its risk factors and ABT are complex. It is difficult to quantify their relative contributions to outcome.15 However, as we and others have shown, preoperative anaemia is common,6,16 easily identifiable and treatable. There is strong evidence that preoperative anaemia and ABT are independent, and that they represent additive risk factors for increased LOS as well as poor postoperative outcome, increased morbidity (including infection) and mortality.17–20 Somewhat surprisingly, these issues have received relatively little attention and to our knowledge, there is only one previous report of a preoperative blood management programme from the UK in the surgical literature.21

The results of this study were presented in part at the British Hip Society meeting held in London in March 2015. There was considerable interest from delegates, and a general feeling that the significance of untreated preoperative anaemia and particularly the negative effect of ABT on outcome was an underrecognised issue among orthopaedic surgeons. NHS England encourages blood management strategies and recommends hospitals should provide ‘arrangements for the timely identification and correction of anaemia before elective surgery which is likely to involve significant blood loss’.22 A survey of hospitals in Yorkshire found that only 2 out of 11 preoperative assessment departments who responded (including our own) had written policies for this; the remainder managed anaemia on a case-by-case basis (unpublished data).

Our baseline prevalence of anaemia and outcomes for transfusion,3,23,24 LOS,25 and readmission25,26 were comparable with other centres. The median nadir Hb trigger for transfusion at baseline was >1g/dl lower than in the OSTHEO study (a large European multicentre study of transfusion following arthroplasty),23 suggesting that our baseline transfusion practice was not excessively liberal. Nevertheless, the striking association between preoperative anaemia and perioperative ABT compelled our unit to implement the NHSBT and Department of Health recommendations regarding blood management.

It was not possible to find an acceptable published algorithm in the literature as other reports of successful blood management programmes used autologous predonation,10,17 which we wanted to avoid. A local algorithm was designed with emphasis on a fairly liberal use of iron for the treatment of iron deficiency anaemia. The rationale behind this was twofold. First, there is evidence that iron sequestration in arthritic joints may make serum ferritin values falsely high in the presence of iron deficiency at bone marrow level.6 Second, iron is cost effective. Oral iron was preferred, with parenteral formulations reserved to avoid postponement of surgery. When the programme started, EPO was expensive (>£100 per 20,000 unit dose) and therefore used sparingly. Our pharmacy has since negotiated a new contract with the manufacturer of Eprex®, making it significantly cheaper (Table 2), and we plan to use it more liberally in the future.

The Network for the Advancement of Transfusion Alternatives published patient blood management guidelines in 2011.11 They suggested that the World Health Organization criteria for anaemia should also be used as treatment thresholds. These thresholds are sex specific while transfusion triggers are not. In our series, women presented with lower preoperative Hb values and subsequently had higher transfusion rates. Sex specific treatment thresholds can therefore expose women to increased risk of transfusion.

Our programme has delivered excellent results with significant improvements in all outcome measures as well as cost savings. For pragmatic reasons, strict compliance with the protocol was relaxed and patients with minor derangements in Hb or ferritin levels were not always treated to avoid postponement of surgery. The transfusion rate following THR has continued to fall between 2010 and 2014, perhaps owing to universal adoption of tranexamic acid, which was initially routine for only one surgeon (the senior author). The continued reduction in Hb loss (from a baseline median of 3.8g/dl to 3.1g/dl in 2010 and 2.2g/dl in 2014) supports this.

There is now a considerable body of level 1 evidence supporting the use of tranexamic acid in arthroplasty surgery. Sukeik et al 27 and Alshryda et al 28 each published a systematic review and meta-analysis in 2011, reporting significant reductions in ABT of 37% (p<0.00001) and 39% (p<0.001) following THR and TKR respectively with the use of tranexamic acid. In our series, the combination of preoperative Hb optimisation and reduced intraoperative blood loss has led to an 80% reduction in ABT for THR and effective cessation of ABT for TKR. In addition to reducing the burden placed on donor blood, a significant reduction in LOS and readmissions was observed. Given that inappropriate early discharge is often associated with increased readmissions, this represents a real outcome change.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This audit cycle has some limitations. Our data are observational. However, the retrospective nature of the final audit minimises Hawthorne effect bias (where outcomes are improved by close observation). It is also not possible to comment on the relative contributions of iron therapy, EPO and tranexamic acid interventions. There are clearly other factors that influence LOS and readmission rates in particular, and it is likely that other aspects of the enhanced recovery pathway such as patient education had some effect on these outcomes. No data were collected on medical co-morbidities, intraoperative blood loss, body mass index, fluid management or reasons for readmission since these are not coded in our hospital databases. Confounding and bias is therefore possible.

On the other hand, this report also has strengths. Data were analysed for a large number of patients from records subject to regular external audit. All groups were very similar in size and the THR-to-TKR ratio was similar to that reported to the National Joint Registry, suggesting excellent sensitivity. Furthermore, our exclusion criteria ensured high specificity. Potential confounders were controlled statistically when baseline predictors of outcome were determined, allowing the baseline group to act as a valid control for evaluating the programme’s effects.

Conclusions

Preoperative anaemia is an underrecognised and easily identifiable predictor of poor outcome after arthroplasty. There are many studies reporting the use of tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss but with little focus on preoptimisation, which we believe to be equally important. Our simple and pragmatic blood management protocol has led to significant reductions in blood transfusion, LOS and readmissions as well as large cost savings. This approach may also be applicable to other elective surgical procedures carrying a high transfusion risk.

Acknowledgement

The project received financial support from the Health Foundation (an independent charity). The grant covered clinician and nursing time to set up and administer the programme during the first year (2010).

References

- 1.NJR StatsOnline National Joint Registry. http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/healthcareproviders/accessingthedata/statsonline/njrstatsonline/tabid/179/default.aspx (cited March 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells AW, Mounter PJ, Chapman CE et al. Where does blood go? Prospective observational study of red cell transfusion in north England. BMJ 2002; : 803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boralessa H, Goldhill DR, Tucker K et al. National comparative audit of blood use in elective primary unilateral total hip replacement surgery in the UK. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2009; : 599–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husted H, Holm G, Jacobsen S. Predictors of length of stay and patient satisfaction after hip and knee replacement surgery. Acta Orthop 2008; : 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A et al. Periprosthetic joint infection: the incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; : 1,710–1,715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spahn DR. Anemia and patient blood management in hip and knee surgery. Anesthesiology 2010; : 482–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Department of Health Better Blood Transfusion. London: DH; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotzé A, Carter LA, Scally AJ. Effect of a patient blood management programme on preoperative anaemia, transfusion rate, and outcome after primary hip or knee arthroplasty: a quality improvement cycle. Br J Anaesth 2012; : 943–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D et al. Publication guidelines for quality improvement studies in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. J Gen Intern Med 2008; : 2,125–2,130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez V, Monsaingeon-Lion A, Cherif K et al. Transfusion strategy for primary knee and hip arthroplasty: impact of an algorithm to lower transfusion rates and hospital costs. Br J Anaesth 2007; : 794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodnough LT, Maniatis A, Earnshaw P et al. Detection, evaluation, and management of preoperative anaemia in the elective orthopaedic surgical patient: NATA guidelines. Br J Anaesth 2011; : 13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muñoz M, García-Erce JA, Cuenca J et al. On the role of iron therapy for reducing allogeneic blood transfusion in orthopaedic surgery. Blood Transfus 2012; : 8–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Theusinger OM, Kind SL, Seifert B et al. Patient blood management in orthopaedic surgery: a four-year follow-up of transfusion requirements and blood loss from 2008 to 2011 at the Balgrist University Hospital in Zurich, Switzerland. Blood Transfus 2014; : 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shander A, Hofmann A, Ozawa S et al. Activity-based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion 2010; : 753–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallis JP. Disentangling anemia and transfusion. Transfusion 2011; : 8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shander A, Knight K, Thurer R et al. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med 2004; 116(Suppl 7A): 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong CJ, Vandervoort MK, Vandervoort SL et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a blood conservation algorithm in patients undergoing total hip joint arthroplasty. Transfusion 2007; : 832–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musallam KM, Tamim HM, Richards T et al. Preoperative anaemia and postoperative outcomes in non-cardiac surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2011; : 1,396–1,407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shander A, Javidroozi M, Ozawa S, Hare GM. What is really dangerous: anaemia or transfusion? Br J Anaesth 2011; : i41–i59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lasocki S, Krauspe R, von Heymann C et al. PREPARE: the prevalence of perioperative anaemia and need for patient blood management in elective orthopaedic surgery: a multicentre, observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015; : 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers BA, Cowie A, Alcock C, Rosson JW. Identification and treatment of anaemia in patients awaiting hip replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2008; : 504–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Blood Transfusion Committee Patient Blood Management. Leeds: NHS England; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosencher N, Kerkkamp HE, Macheras G et al. Orthopedic Surgery Transfusion Hemoglobin European Overview (OSTHEO) study: blood management in elective knee and hip arthroplasty in Europe. Transfusion 2003; : 459–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spahn DR. Anemia and patient blood management in hip and knee surgery. Anesthesiology 2010; : 482–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dr Foster Hospital Guide 2010. London: Dr Foster; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cullen C, Johnson DS, Cook G. Re-admission rates within 28 days of total hip replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006; : 475–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, Mason JM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; : 39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alshryda S, Sarda P, Sukeik M et al. Tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; : 1,577–1,585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]