Abstract

Introduction

Surgical site infection (SSI) is a significant cause of postoperative morbidity and mortality. Effective preoperative antisepsis is a recognised prophylactic, with commonly used agents including chlorhexidine (CHG) and povidone-iodine (PVI). However, there is emerging evidence to suggest an additional benefit when they are used in combination.

Methods

We analysed data from our prospective SSI database on patients undergoing clean cranial neurosurgery between October 2011 and April 2014. We compared the case-mix adjusted odds of developing a SSI in patients undergoing skin preparation with CGH or PVI alone or in combination.

Results

SSIs were detected in 2.6% of 1146 cases. Antisepsis with PVI alone was performed in 654 (57%) procedures, while 276 (24%) had CHG alone and 216 (19%) CHG and PVI together. SSIs were associated with longer operating time (p<0.001) and younger age (p=0.03). Surgery type (p<0.001) and length of operation (p<0.001) were significantly different between antisepsis groups. In a binary logistic regression model, CHG and PVI was associated with a significant reduction in the likelihood of developing an SSI (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.12, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.02–0.63) than either agent alone. There was no difference in SSI rates between CHG and PVI alone (AOR 0.60, 95% CI 0.24–1.5).

Conclusions

Combination skin preparation with CHG and PVI significantly reduced SSI rates compared to CHG or PVI alone. A prospective, randomized study validating these findings is now warranted.

Keywords: Antisepsis, Chlorhexidine, Neurosurgery, Povidone-iodine, Surgical wound infection

Surgical site infection (SSI) remains a significant and avoidable cause of postoperative morbidity and mortality.1 It adversely effects patient quality of life, length of hospital stay and cost of care.1–3 In neurosurgery, these consequences, although relatively infrequent, are often more extreme, commonly requiring admission, reoperation and/or prolonged intravenous antibiotic therapy.4–6

Effective preoperative antisepsis is considered a key element in preventing SSIs. The two most commonly used antiseptic agents are chlorhexidine (CHG) and povidone-iodine (PVI).7 While combining them with alcohol is widely considered to be more effective,8 it is not clear which of the two agents is the most effective, despite the publication of a number of meta-analyses.7,9–12

CHG and PVI have different mechanisms of action and different spectrums of efficacy. CHG damages the outer microbial layers, upsetting resting membrane potentials, whereas PVI uncouples iodine, which is absorbed by microbes to inactive key cytoplasmic pathways.13 Their concurrent use had long been held to be deleterious. This been challenged in vivo, however.13

We determined whether preoperative skin preparation using a combination of CHG and PVI was associated with a lower SSI rate than either agent alone in patients undergoing clean cranial neurosurgery.

Methods

We analysed data prospectively collected on the departmental database of the Greater Manchester Neurosciences centre. This records patient age and sex, alongside SSI risk factors such as American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system (ASA) grade, surgery within the last month, Altemeier wound class,14 length of operation, emergency or elective surgery, grade of operating surgeon and type of surgery.

All cranial, neurosurgical procedures are recorded on the database and followed up prospectively on a daily by a dedicated SSI nurse to identify SSIs. These are defined in line with UK Health Protection Agency (HPA) guidance as requiring one of: purulent discharge; a positive wound culture (superficial or intraoperative); or a clinical diagnosis of infection either at the operative site within 30 days of the procedure or within 1 year where an implant(s) remains.5,15 Following discharge clinic appointments, telephone consultation or postal questionnaires, alongside daily review of the neurosurgical referral database and hospital readmissions, are monitored to identify SSIs. This multifaceted patient follow-up has been shown to be more reliable at identifying SSI than questionnaire-based follow-up alone.5

The surveillance programme also includes a form that the operating surgeon completes at the time of surgery to record the type of preoperative antisepsis, including the number and type of preparations used. Completing the form was not mandatory, however, and therefore not all cases record this data.

The choice of preoperative skin antisepsis was based on surgeon preference. CHG was available as ChloraPrep (Carefusion, San Diego, CA, USA) or Hydrex Pink (Ecolab, St Paul, MN, USA). PVI was available as Vidine alcoholic tincture or antiseptic solution (Ecolab, St Paul, MN, USA).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All cranial, neurosurgical procedures between October 2011 and April 2014 in which information on preoperative antisepsis had been prospectively completed were reviewed. Only patients undergoing a clean,14 cranial neurosurgical procedure were included. Procedures requiring an implant were excluded. SSIs in patients who underwent preoperative skin preparation using CHG or PVI as a single agent, or a combination of the two agents, were then extracted from the database.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between study groups and in relation to the development of SSIs to identify potential confounders. Categorical variables were assessed using the Chi-squared test; continuous, normally distributed variables were examined using analysis of variance; and continuous, non-normally distributed variables were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis tests. Normality was examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Case mix adjustment was then performed with statistically determined and clinically relevant variables, using binary logistic regression. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

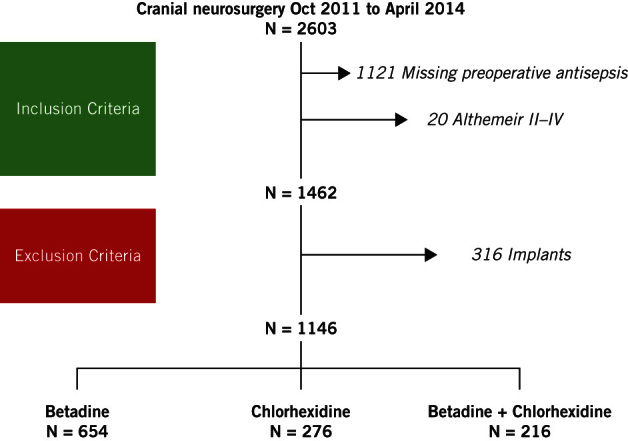

Between October 2011 and April 2014, 2603 cranial neurosurgical procedures were performed at our centre, of which 94 (3.6%) were complicated by SSI. The type of surgical skin preparation was recorded prospectively in 1146 (44%) of cases. (Figure 1). Of the 1146 cases included in this study, 654 (57%) underwent preoperative antisepsis with PVI alone, 276 (24%) with CHG alone and 216 (19%) with a combination of CHG and PVI.

Figure 1.

STROBE flow diagram of patient selection

SSIs were detected in 2.6% of cases, with the majority caused by skin commensals (60%), of which the majority were Staphylococcus species (Table 1). Other cultured organisms included Enteroccous, Morexella, Diphtheria and Pseudomonas species. The cultures were negative in three cases.

Table 1.

Cultured microorganisms by type of antiseptic skin preparation

| Organisms cultured (p=0.99) | |||

| Variable | PVI | CHG | CHG + PVI |

|

Staphylococcus aureus Coagulase Negative Staphylococcus Other No growth |

9 (43) 4 (19) 7 (33) 1 (5) |

4 (57) 0 (0) 1 (14) 2 (29) |

1 (50) 0 (0) 1 (50) 0 (0) |

All values n (%), unless otherwise stated

CHG = chlorhexidine; PVI = povidone-iodine

Longer operation times (p<0.001) and younger patient age (p=0.03) were significantly associated with the occurrence of SSIs (Table 2). In contrast, patient sex, age, type and urgency of surgery showed no association. The type (p<0.001) and length of surgery (p <0.001) were significantly different between antiseptic groups, with patients receiving combination CHG and PVI found to have the longest mean operating time (Table 3).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of baseline characteristics by presence of SSI

| Variable | SSI | No SSI | P value |

| Male Age, years (IQR) ASA Good (I-III) Poor (IV-V) Operating time, minutes (IQR) |

18 (60) 52 (30) 15 (50) 15 (50) 180 (125) |

594 (53) 57 (26) 710 (64) 406 (36) 110 (120.5) |

0.76 0.03* 0.13 0.001* |

| Category of surgery Oncology Vascular Trauma/Emergency Miscellaneous |

18 (60) 4 (13) 2 (7) 6 (20) |

698 (63) 101 (9) 216 (19) 101 (9) |

0.08 |

| Emergency surgery | 7 (23) | 336 (30) | 0.42 |

* Significant <0.05. All values n (%), unless otherwise stated

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system; IQR = interquartile range; SSI = surgical site infection

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of baseline characteristics by type of antiseptic

| Variable | PVI | CHG | CHG + PVI | P value |

| Male Age, years (IQR) ASA Good (I-III) Poor (IV-V) Operating time, minutes (IQR) |

362 (55) 57 (25) 425 (65) 229 (35) 105 (115) |

139 (50) 58 (25) 166 (60) 110 (40) 105 (106.5) |

111 (51) 55 (22) 134 (62) 82 (38) 152 (172.5) |

0.52 0.15 0.35 <0.0001* |

| Category of surgery Oncology Vascular Trauma/Emergency Miscellaneous Emergency Surgery |

455 (70) 19 (3) 142 (22) 38 (6) 202 (31) |

158 (57) 14 (5) 52 (19) 52 (19) 82 (30) |

103 (48) 72 (33) 24 (11) 17 (8) 59 (27) |

<0.0001* 0.61 |

* Significant <0.05. All values n (%), unless otherwise stated

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification system; CHG = chlorhexidine; IQR = interquartile range; PVI = povidone-iodine

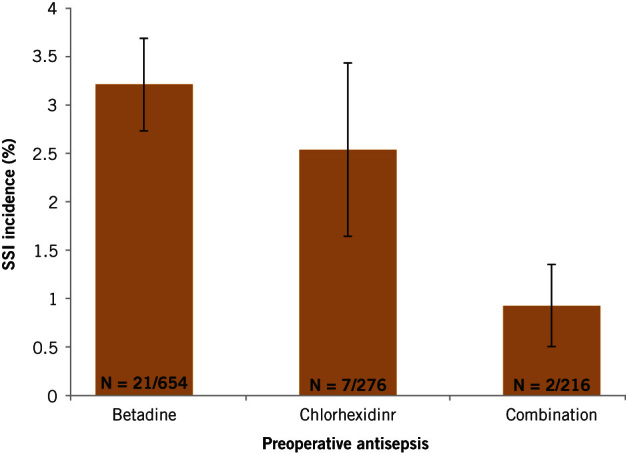

The crude SSI rate in patients receiving CHG and PVI was lower (0.9%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.5–1.4) than that in patients who had PVI (3.2%, 95% CI 2.7–3.7) or CHG (2.5%, 95% CI 1.6–3.4) alone, although the difference was not significant (p=0.18) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Incidence of SSI within each preoperative antisepsis group, with 95% confidence intervals

A binary logistic regression model taking into account length and type of operation, patient age and ASA indicated that the combination of CHG and PVI was associated with a significant reduction in the likelihood of developing an SSI versus either preparation alone (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.12, 95% CI 0.02–0.63, p=0.01). There was no difference in the likelihood of developing an SSI between CHG and PVI alone (AOR 0.60 95% CI 0.24–1.5, p=0.28).

Discussion

Our results show that the preoperative use of CHG and PVI reduces the risk of SSI by 88% among patients undergoing cranial neurosurgery compared with either preparation alone. We did not observe any difference in SSI risk between patients prepped with CHG or PVI alone.

The rationale and aim of preoperative skin preparation is to remove transient organisms and reduce the number of skin commensals, as they are the most common cause of SSI.5,7 Our data is consistent with this concept, as skin commensals were the most commonly observed organisms responsible for SSI.

There has been much debate over which antiseptic agent reduces SSI most efficiently, and many trials have been conducted.7,9,11,12,16 The most recent Cochrane review indicated that preoperative skin preparation with 0.5% CHG and methylated spirits was associated with lower rates of SSI in clean surgery than an alcohol-based PVI skin preparation.7 Our study, which is one of the larger analyses of SSI rates between CGH and PVI, did not demonstrate any net benefit of one skin preparation over another. This data supports the evidence from the literature. Moreover, even the authors of the Cochrane review note that the reduction in SSI rates associated with CHG was due to a single trial that was subject to bias. It has therefore been argued that a better-designed, larger trial is needed to definitively answer the issue over which preparation to use. We would argue that, despite the heterogeneity of the trials analysed and their well-characterised biases, the lack of emergence of a single agent from a pooled analysis of 2623 patients suggests that the entire strategy of SSI reduction needs to be reconsidered.

Few authors have compared SSI rates in patients receiving preoperative skin preparation with two agents versus a single agent. The combination of CHG and PVI had, for many years, been considered deleterious. Although careful sequential application would circumvent this, a 2010 in vivo study by Anderson et not only did not support these negative effects but also found evidence of a synergistic effect.13 They postulate that the membrane disruption provided by CHG facilitates greater PVI uptake. The clinical literature on their combination is limited to a single randomised trial in patients undergoing caesarean section, which demonstrated better SSI rates in obese patients receiving dual preoperative skin preparation versus those who did not.17 The approach is also supported by a number of studies that have demonstrated better decontamination rates of skin microorganisms at the incision site with double-agent skin preparation.13,18–21

We accept that this is a retrospective analysis, and may therefore be biased by incomplete case acertainment due the skin preparation type having not been recorded for all surveillance cases. We do, however, have robust prospective identification of all patients, a robust definition of SSI and the prospective follow-up of patients to record the occurrence of an SSI, which allows for a meaningful interpretation of our data.

Conclusions

SSI remains a significant burden for patients, hospitals and clinicians alike, and advances in prevention are required. This analysis of prospectively collected data demonstrates a significant reduction in SSIs in patients whose surgical site was prepared with a combination of CHG and PVI, thus adding to the evidence supporting its greater efficacy in surgical site decolonisation. Our results require formal validation in a well-powered, prospective, randomised trial.

References

- 1.Coello R, Charlett A, Wilson J et al. Adverse impact of surgical site infections in English hospitals. J Hosp Infect 2005; : 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL et al. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999; : 725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broex EC, van Asselt AD, Bruggeman CA et al. Surgical site infections: how high are the costs. J Hosp Infect 2009; : 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu Hamdeh S, Lytsy B, Ronne-Engström E. Surgical site infections in standard neurosurgery procedures- a study of incidence, impact and potential risk factors. Br J Neurosurg 2014; : 270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies BM, Jones A, Patel HC. Surgical-site infection surveillance in cranial neurosurgery. Br J Neurosurg 2015; 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Keeffe AB, Lawrence T, Bojanic S. Oxford craniotomy infections database: a cost analysis of craniotomy infection. Br J Neurosurg 2012; : 265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dumville JC, McFarlane E, Edwards P et al. Preoperative skin antiseptics for preventing surgical wound infections after clean surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; : CD003949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maiwald M, Chan ES. The forgotten role of alcohol: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical efficacy and perceived role of chlorhexidine in skin antisepsis. PLoS ONE 2012; : e44277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noorani A, Rabey N, Walsh SR et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of preoperative antisepsis with chlorhexidine versus povidone-iodine in clean-contaminated surgery. Br J Surg 2010; : 1,614–1,620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sidhwa F, Itani KM. Skin preparation before surgery: options and evidence. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2015; : 14–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee I, Agarwal RK, Lee BY et al. Systematic review and cost analysis comparing use of chlorhexidine with use of iodine for preoperative skin antisepsis to prevent surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; : 1219–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadiati DR, Hakimi M, Nurdiati DS et al. Skin preparation for preventing infection following caesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; : CD007462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson C, Uman G, Pigazzi A. Oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol 2008; : 1,135–1,142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altemeier WA, Burke JF, Pruitt BA et al. Manual on Control of Infection in Surgical Patients Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Protocol for the Surveillance of Surgical Site Infection London: Health Protection Agency, 2014. pp1–75. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darouiche RO, Wall MJ, Itani KM et al. Chlorhexidine-Alcohol versus Povidone-Iodine for Surgical-Site Antisepsis. N Engl J Med 2010; : 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ngai I, Govindappagari S, Van Arsdale A et al. LB1: Skin preparation in cesarean birth for prevention of surgical site infection (SSI): a prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015; : S424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guzel A, Ozekinci T, Ozkan U et al. Evaluation of the skin flora after chlorhexidine and povidone-iodine preparation in neurosurgical practice. Surg Neurol 2009; : 207–10; discussion 210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langgartner J, Linde HJ, Lehn N et al. Combined skin disinfection with chlorhexidine/propanol and aqueous povidone-iodine reduces bacterial colonisation of central venous catheters. Intensive Care Med 2004; : 1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sellers J, Newman JH. Disinfection of the umbilicus for abdominal surgery. Lancet 1971; : 1,276–1,278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.May SR, Roberts DP, DeClement FA et al. Reduced bacteria on transplantable allograft skin after preparation with chlorhexidine gluconate, povidone-iodine, and isopropanol. J Burn Care Rehabil 1991; : 224–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]