Abstract

Type 2 diabetes is a major public health problem in the USA, affecting over 12 % of American adults and imposing considerable health and economic burden on individuals and society. There is a strong evidence base demonstrating that lifestyle behavioral changes and some medications can prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes in high risk adults, and several policy and healthcare system changes motivated by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) have the potential to accelerate diabetes prevention. In this narrative review, we (1) offer a conceptual framework for organizing how the ACA may influence diabetes prevention efforts at the level of individuals, healthcare providers, and health systems; (2) highlight ACA provisions at each of these levels that could accelerate type 2 diabetes prevention nationwide; and (3) explore possible policy gaps and opportunity areas for future research and action.

Keywords: Diabetes, Prediabetes, Primary prevention, Health policy, Affordable Care Act

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is a major public health problem in the USA, affecting over 12 % of adults and imposing considerable health and economic burden on individuals and society [1, 2]. Because obesity, dietary composition, and physical inactivity are key drivers of the development of type 2 diabetes, it is largely a socially and environmentally determined condition and is preventable [3, 4]. Preventing diabetes will require interventions at multiple levels, spanning public policy to individual counseling [5–7], all ultimately aligned to encourage and enable healthier lifestyle behaviors that can reduce harmfully elevated blood glucose levels [8, 9].

In the USA today, 86 million Americans, or more than one in three adults have been classified as having “prediabetes,” a condition characterized by blood sugar levels that are higher than normal but not high enough to be considered diabetes [1]. Approximately 5–10 % of people with prediabetes develop diabetes each year, and 70 % will do so during their lifetime [10, 11]. Diabetes is a considerable threat to population health, spares no segment of society, and disproportionately affects the poor, the aged, and racial and ethnic minorities [1, 12]. Given these staggering statistics, primary prevention is critical to reduce the future population burden of diabetes.

A large body of research demonstrates the role that health services and individual behavior can play in preventing diabetes among adults with prediabetes [13–16]. The US Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) clinical trial and subsequent translational studies have demonstrated that intensive lifestyle interventions focused on achieving 7 % weight loss and at least 150 min per week of moderate physical activity can cut the risk of developing diabetes in half [8, 17]. Such interventions also improve health-related quality of life [18], enable some patients to reduce the need for medications [19], and may lower future healthcare expenditures [10, 20, 21]. The DPP and other trials also found that metformin, a medication often used to treat diabetes, as well as other select medications, are efficacious treatments for preventing diabetes [8, 14]. While past research has demonstrated that the benefits of lifestyle interventions and metformin begin within 3 to 6 months and can last for more than a decade [8, 22], the delivery of these individual interventions are alone not sufficient for diabetes prevention at the population level [3, 23, 24*].

Policy, systems, and environmental changes (PSE) are also essential elements of a long-term agenda to prevent chronic diseases like diabetes [7, 25, 26]. Policies and environmental changes function to make healthy behaviors more accessible or desirable and unhealthy exposures more difficult or even prohibited. System-level interventions aim to improve the functioning of an agency or organization, as well as the delivery of its services to the community. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) [27] represents a collection of PSE interventions creating many opportunities to accelerate diabetes prevention on a national scale [27–30]. Through a simultaneous focus on individuals, healthcare providers, health systems, and community resources, the ACA targets multiple levels of influence—an approach widely advocated by public health authorities for tackling diabetes prevention at scale [6, 31].

While some prior reports have described how the ACA may impact national diabetes prevention efforts [28–30, 32], they were written prior to the law’s full implementation and would benefit from an update. Recent reports have also highlighted a gap in high-quality research to evaluate diabetes prevention policies [5, 33, 34]. for these reasons, we conducted a narrative review to (1) offer a conceptual framework for organizing how the ACA may influence diabetes prevention efforts at the level of individuals, healthcare providers, and health systems; (2) highlight ACA provisions at each of these levels that could accelerate type 2 diabetes prevention nationwide; and (3) explore possible policy gaps and opportunity areas for future research and action.

Methods

Our review began with an electronic search of PubMed and Google Scholar, combining MeSH headings and keywords related to diabetes (i.e., “diabetes mellitus,” “prediabetic state,” “diabetes prevention,” OR “prevention of diabetes”) along with terms relating to policy actions (i.e., “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,” “ACA,” OR “policy”). Articles published during or after 2010, the year the ACA became law, were considered, with no other explicit inclusion or exclusion criteria. Because of our goal to describe the broad state of policy actions, we did not restrict the literature search on whether an evaluation had already taken place or if that evaluation met particular criteria for methodological rigor.

Titles of all identified reports were reviewed for their relevance, and full manuscripts for all relevant reports were retrieved and reviewed. Two authors also reviewed and summarized relevant provisions from the ACA. We then reached out to expert stakeholders at relevant agencies or organizations, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the American Medical Association (AMA), and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) to request further descriptions.

Our search did not identify any prior systematic reviews or strong research studies directly relating healthcare-focused policy and systems interventions with the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Given this evidence gap, we elected to propose a framework for organizing how ACA interventions might prevent type 2 diabetes. We used an iterative process of group discussion and mapping of relevant policy domains to the framework and developed a narrative to highlight key findings, gaps, and implications identified from all relevant data sources.

Discussion

Diabetes Prevention Care Continuum Framework

Given a strong evidence base demonstrating that lifestyle behavioral changes and some medications prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes in high risk adults [13–16], we elected to organize the conceptual framework primarily to depict how healthcare policy and system changes could support or enable those behaviors, particularly among high-risk individuals. Conceptually, PSE addressing broader domains such as community safety, healthy food access, or the creation of environments to support physical activity are also likely to achieve type 2 diabetes prevention on a larger scale, but are beyond the scope of this review. Readers are directed to past reports that focus more specifically on these broader areas [4, 35–37].

The framework conceptualizes preventive behaviors as emerging from more supportive environments, social support systems, or participation in evidence-based interventions targeting individuals or small groups. Because the current economic, social, cultural, and physical environment in the USA is not sufficiently supportive of behaviors that prevent obesity or type 2 diabetes [37], the ACA targets the health system and its interface with community and public health systems, as vehicles for affecting behavioral change.

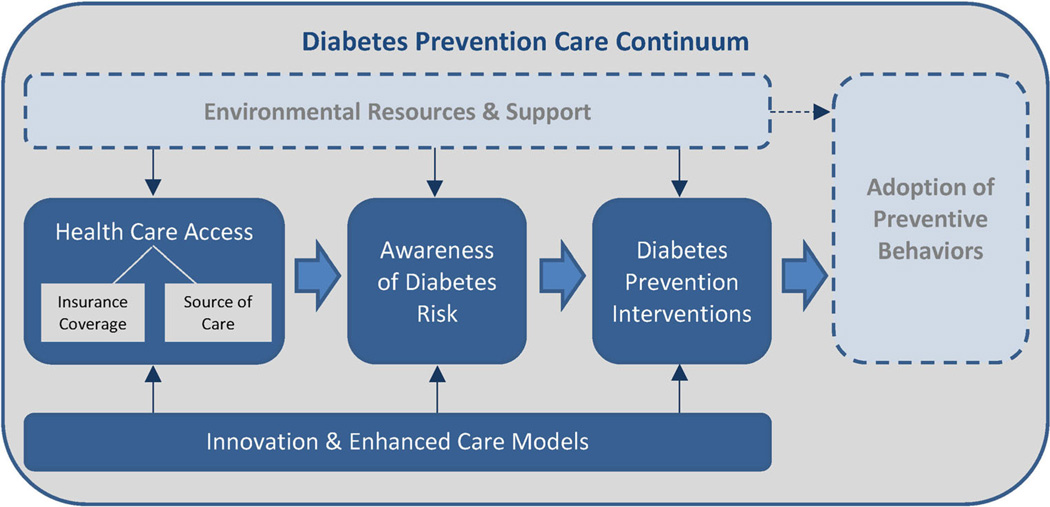

However, when the broader environment is largely unsupportive, behavioral change requires individuals to be aware, motivated, and strongly supported. Current recommendations for raising individual awareness of diabetes risk require testing of blood glucose or hemoglobin A1c within the health system [38]. For this reason, the ACA attempts to expand access to prepared and proactive healthcare personnel and services to enable risk assessment, the raising of awareness, and access to supportive interventions at individual, system, and community levels. This continuum is depicted in Fig. 1 and described further below.

Fig. 1.

The Diabetes Prevention Care Continuum. Policies, systems, and environmental changes are conceptualized as having the potential to influence diabetes prevention via beneficial behavioral changes that occur by two major pathways. The first pathway, depicted by the rectangle at the top of the figure, involves changes in the social, cultural, economic, or physical environment that function either to make healthy behaviors more accessible or desirable and unhealthy exposures more difficult or prohibited. The second pathway involves improvements in the functions or activities of health systems and the interfacing of those systems with public health agencies or community organizations to raise awareness and expand delivery of evidence-based diabetes prevention interventions. This second pathway, depicted in the middle of the figure with the large, solid arrows moving from left to right, is the primary focus of this review. The thin solid arrows indicate other forces, namely, the first pathway and innovation, which influences this second pathway. The dotted arrow represents the effect of the first pathway on the adoption of healthy behaviors at the individual level. See text for further description.

Affordable Care Act and its Effect on the Diabetes Prevention Care Continuum

Access to Health Care

Access to health care is a multidimensional concept, including availability, organization, financing, utilization, and satisfaction [39]. Several provisions in the ACA extend healthcare access to millions of Americans through expansions of health insurance coverage and accessibility to healthcare providers (Table 1). Importantly, because many chronic conditions such as diabetes disproportionally affect certain population subgroups, such as racial/ethnic minorities and those facing socioeconomic disadvantage, several ACA provisions were also designed to ensure that these groups have equitable access to health insurance coverage and to a patient-centered medical home where they can receive evidence-based preventive services at low or no cost.

Table 1.

ACA provisions related to the Diabetes Prevention Care Continuum

| ACA provision (section) | Description |

|---|---|

| Access to health care | |

| Insurance coverage | Coverage improves access to diabetes preventive and educational services offered by healthcare systems |

| Medicaid expansion (Section 2001) | Medicaid eligibility expanded to all individuals with income ≤138 % of the Federal Poverty Level beginning 1 January 2014. Not all states have elected to expand. |

| Creation of an Insurance Exchange “Marketplace” (Section 1311) |

Affordable choices of health benefit plans enhancing access; the individual mandate for purchasing coverage enables community rating of health insurance risks and lower out-of-pocket expenditures for individuals. |

| Source of care | Expanded focus on primary and preventive care creates more opportunity for diabetes prevention. |

| Initiatives to expand the primary care workforce (Sections 5301; 5501; 5503) |

Higher reimbursements to primary care providers in health professional shortage areas; expands medical residency positions, enables grants to primary care training programs; extends financial assistance to individuals who intend to pursue a career in primary care |

| Initiatives to support delivery-system changes to improve chronic disease prevention and management (Sections 2703; 3502; 4101; 5208; 5601; 10503) |

Provides states an option to enroll Medicaid beneficiaries with 2 or more chronic conditions (including diabetes and overweight) into a “Health Home” that receives payment for a team-based approach to providing chronic care services; expands funds for Federally Qualified Health Centers, school-based health centers, and nurse- managed health clinics offering health promotion/ disease prevention services; provides grants to establish community-based interdisciplinary, inter-professional “health teams” to support primary care practices; ensures continuity of coverage |

| Awareness of diabetes risk | |

| Clinical and community preventive services (Section 4003) |

Improves the coordination between USPSTF and the Community Preventive Services Task Force; both have now issued strong recommendations to offer intensive lifestyle interventions to adults with prediabetes. |

| Education and outreach campaign regarding preventive benefits (Section 4004) |

Directs the Secretary to conduct a national prevention and health promotion outreach and education campaign to raise awareness of health promotion and disease prevention activities |

| Expanded coverage for preventive health services by commercial and public health payers (Sections 2713; 4104; 4106) |

Requires non-grandfathered commercial health plans, Medicare, and Medicaid expansion program coverage of USPSTF “A/B” recommendations for clinical preventive services; also provides states additional federal reimbursement (FMAP) for preventive services if they elect to adopt under traditional Medicaid programs; USPSTF has recommended prediabetes screening for overweight/obese adults aged 40–70 |

| Medicare coverage of annual wellness visit (Section 4103) |

Directs the reimbursement by Medicare for an annual wellness visit focused on enacting a personalized prevention plan for each beneficiary |

| Provisions to expand employer-based wellness programs (Sections 2705; 4303; 10408) |

Expands incentives and provides technical assistance to employers to offer comprehensive wellness programs that include but are not limited to health risk appraisal and education (incentives for programs are listed under interventions below) |

| Community Transformation and Healthy Aging/Living Well Grants (Sections 4201 & 4202) |

Grants to health departments and community organizations to provide education, raise awareness, and conduct screenings across the full-age spectrum |

| Diabetes prevention interventions | |

| Prevention and Public Health Fund (4002) | Expands funds for the implementation and evaluation of prevention and public health activities, including but not |

| limited to the National Diabetes Prevention Program and Community Transformation Grants; partially funds grants made by the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion for state and local public health initiatives to prevent and control diabetes, heart disease, stroke, obesity, and other related risk factors (see text for details) |

|

| National Diabetes Prevention Program (Section 10501) |

Established a national program, coordinated by CDC, to build workforce and programmatic capacity for evidence-based diabetes prevention programs nationally |

| Essential Health Benefits Requirements (Section 1302) |

Requires commercial health plans to offer a package of essential health benefits and limits cost-sharing; includes preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management |

| Expanded coverage for preventive health services by commercial and public health payers (Sections 2713; 4104; 4106) |

Requires non-grandfathered commercial health plans, Medicare, and Medicaid expansion program coverage of USPSTF “A/B” recommendations for clinical preventive services; also provides states additional federal reimbursement for preventive services if they elect to adopt under traditional Medicaid programs; USPSTF has recommended intensive lifestyle intervention services such as the Diabetes Prevention Program for overweight/obese adults with prediabetes |

| Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases in Medicaid (Section 4108) |

Provides grants to states to implement and evaluate a program that provides incentives directly to Medicaid beneficiaries with select chronic disease risk conditions (including prediabetes) to participate in an evidence- based prevention program or service consistent with those recommended by the USPSTF or Community Preventive Services Task Force |

| Community-based Prevention and Wellness Programs for Medicare Beneficiaries (Section 4202) |

CDC grants to state or local health departments to carry out 5-year pilot programs including community interventions, screenings, and, where appropriate, clinical referrals for individuals between ages 55 and 64 |

| Provisions to expand employer-based wellness programs (Sections 2705; 4303; 10408) |

Expands incentives and provides technical assistance to employers to offer comprehensive wellness programs and to extend participation incentives to a wide array of employees with different health risks; extends funding to implement and evaluate wellness programs |

| Nutrition Food Labeling Requirements (Section 4205) |

Requires chain restaurants and vending machine owners to display nutrient composition information along with recommended daily caloric intake information for standard menu and food sale items |

| Innovation and enhanced care models | |

| Establishment of Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (Section 3021) |

Established to develop, evaluate, and expand innovative payment and service delivery models; designed to improve quality and reduce the cost of care; dedicated funding is provided to allow for testing of models that require benefits not currently covered by Medicare; successful models can be expanded nationally; a large- scale evaluation of offering community DPP interventions to Medicare beneficiaries is underway (see text) |

| Medicare Shared Savings Program (Section 3022) |

Rewards ACOs for reducing costs and improving quality of care over time; should encourage population health management activities that target individuals at high risk for chronic conditions to participation in preventive services |

| Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (Section 6301) |

Established the Institute to address questions most relevant to patients; funds comparative clinical effectiveness |

| research with a goal of improving evidence available to patients, providers, and other stakeholders involved in making healthcare decisions |

|

| Research on optimizing the delivery of public health services (Section 4301) |

Funds public health services and systems research, focusing on high-priority areas, including prevention, as identified in the National Prevention Strategy or Healthy People 2020 |

| Provisions to ensure quality of care (Section 2717) |

Creation of reporting requirements for insurers regarding efforts to improve health outcomes including care coordination, chronic disease management, hospital readmission prevention, wellness and health promotion, and patient safety and quality improvement efforts |

| Quality measure development (Sections 2701; 3013; 3014) |

Authorized funding for the development and endorsement of quality measures at AHRQ and CMS; directs the Secretary of HHS to develop and report on a set of quality measures for Medicaid eligible adults |

| Better Diabetes Care (Section 10407) | Directs the preparation of a bi-annual national diabetes report card and, if feasible, state diabetes report cards that include outcomes for individuals with diabetes and prediabetes; includes preventive care practices and quality aggregate measures |

Data pooled from the following resources: ACA [27], National Association of County and City Health Officials [81], Trust for America’s Health [82], Obamacare Facts [83]

ACA Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, CMS Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, USPSTF United States Preventive Services Task Force, CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ACO Accountable Care Organization, AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, HHS United States Department of Health and Human Services

Insurance Coverage

One of the central goals of the ACA was to expand insurance coverage to eligible Americans who previously lacked health insurance. Pursuant to the ACA, the US Department of Health and Human Services reported a 35 % decrease in the number of uninsured adults between 2012 and the first quarter of 2015 [40]. Among the many provisions contributing to this effort, the ACA established the insurance marketplace (“exchanges”), which gives individuals the option of purchasing private qualifying health insurance plans independent of an employer. Early reports indicate that the ACA was successful in decreasing the number of Americans who have unpaid medical bills and those who report delaying care because of cost [41]. Additionally, the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid in several states increased eligibility to those at or below 138 % of the poverty level, a particularly vulnerable population. One recent report concluded that in states where Medicaid was expanded, there was a 23 % increase in the identification of diabetes [42*]. Though rates of newly identified prediabetes were not reported, both diabetes and prediabetes are detected using the same blood tests, so it is likely that identification of prediabetes has also increased by these coverage expansions. This increase in the diagnosis of diabetes is consistent with the findings from the pre-ACA Oregon Medicaid expansion in 2008, where Medicaid coverage significantly increased diabetes detection by 3.83 percentage points (95% CI 1.93 to 5.73.) [43]. However, while medication treatment for diabetes also significantly increased, there was no significant effect on glycosylated hemoglobin levels.

The ACA also mandates coverage of all US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) A or B recommendations, without cost-sharing, by Medicare and all non-grandfathered commercial health plans [27]. Medicaid plans that are designed for groups targeted by new coverage expansions also must cover these services without cost-sharing. For traditional Medicaid populations, states can choose to cover these services without cost-sharing, and if they do so the federal government will pay the state for an additional 1 % of the cost of each service [44]. To the extent that health insurance and access to a usual source of care provide coverage for a minimum set of evidence-based preventive services, the ACA may improve the detection of prediabetes, as well as access to interventions to help prevent the development of type 2 diabetes. These two areas are described further below.

Source of Care

Insurance alone does not guarantee access to appropriate care. The identification, prevention, and management of highly prevalent chronic health states, including prediabetes and diabetes, require a primary care system with multidisciplinary, prepared, and proactive healthcare teams [45–48]. The ACA makes several strides towards strengthening primary care through its enhanced investment in federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and health homes and its efforts to expand the primary care and community health workforces. Health homes (or patient-centered medical homes) are considered a quintessential component of successful population health management, combining delivery system innovations, self-management support, and technological interventions that have been linked to better diabetes care quality [49, 50] and preventive services [51]. Furthermore, the ACA encourages innovative forms of value-based payment designs to improve care coordination, as well as other approaches for population health management. To the extent that these innovations may encourage targeting and more proactive management of individuals at high risk for developing diabetes, they are discussed separately below, under Innovation and Enhanced Care Models.

Gaps

We were unable to find strong evidence linking ACA coverage expansions directly to improved access to diabetes prevention interventions or adoption of behaviors. Similarly, although there is a compelling rationale for how medical homes might promote health and prevent chronic disease, there has been little evidence to date demonstrating that these strategies will directly improve diabetes prevention.

It is also evident that the ACA has reduced the numbers of uninsured Americans, but many still live without health insurance or a medical home. Almost half of US states opted not to expand their Medicaid programs, leaving at least 4 million low-income American adults still without coverage for evidence-based preventive services [52]. In addition, access to health care may be a necessary step in clinical diabetes prevention but is not sufficient [53]. The ACA’s coverage expansions do not ensure that health delivery systems will provide the right care at the right time in an effective and efficient manner, including diabetes prevention strategies. Since the ACA has not provided universal health insurance or medical home access, many high-risk Americans will still not receive essential preventive services, including prediabetes screening and evidence-based interventions through health insurance. It will be important not only to consider where current policy gaps exist but also to evaluate the impact of these and other existing policies on population-based diabetes prevention.

Awareness of Diabetes Risk

Currently, 9 in 10 Americans with prediabetes are unaware of their high risk status [54]. As such, lack of awareness of one’s risk or of the availability of interventions to reduce risk are barriers. ACA’s provisions for access to evidence-based preventive services are extremely helpful, but it is the nature of those recommended services that could specifically accelerate awareness of prediabetes and its management. In October 2015, the USPSTF issued a new “B” recommendation for screening for abnormal blood glucose in overweight or obese adults ages 40 to 70 [55]. This broad screening recommendation has the potential to identify greater numbers of people at high risk for developing type 2 diabetes, which opens the door for taking action to prevent the onset of diabetes.

One’s workplace can also serve as a channel for raising awareness, appraising health risks, and encouraging linkages to health care when appropriate. Given that the average working-age American adult spends less than 1 to 2 hrs per year in a clinician’s office but almost 2000 or more hours at work, the ACA also included provisions meant to equip CDC to provide financial and technical support for expanding well-ness programs, and to increase the incentives employers are allowed to offer employees for participation in those programs. To date, however, no details have been shared publicly about findings or best practices.

Gaps

One potential policy gap in raising awareness is that not all people with elevated risk for diabetes are included in the new USPSTF screening recommendation. For example, in the 2009–2010 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, about 29 % of Americans ages 12 and older who had an A1c ≥5.7 % were not overweight or obese, and 26 % were less than age 45 [56]. These individuals would currently fall outside the target population of the USPSTF screening recommendation. Because adults of minority race or ethnicity are more likely to develop prediabetes or type 2 diabetes at younger ages and a leaner body mass [12], it is possible that the simple age- and body mass-driven screening recommendation could widen disparities in prediabetes detection.

Another potential gap is that neither health insurance coverage nor clinical practice recommendations are sufficient to ensure that screening and detection occur routinely [57]. Moreover, detection does not equal awareness. Additional action is needed to ensure that healthcare providers are prepared to communicate risk effectively, and to empower high risk patients to make informed decisions about prediabetes management. Large organizations such as the AMA, ADA, and joint efforts such as the National Diabetes Education Program provide tools and resources that can promote effective risk communication, action planning, and follow-up of high-risk patients [58, 59]. Unfortunately, there has been little research to date on communication strategies that are most effective for empowering patients to take action.

A final gap is the challenge of enforcing the ACA’s preventive service coverage requirement. Prior analyses of health plan coverage policies for preventive services have suggested that no-cost preventive services have been adopted inconsistently or that health plan enrollees are often not made fully aware of the services covered [60*, 61]. A 2014 Kaiser Family Foundation study also found that only 43 % of individuals were aware of the elimination of cost-sharing for preventive benefits under the ACA [62]. If coverage of recommended diabetes prevention services are to have a measurable impact, it will be important to evaluate implementation and explore how best to encourage or regulate consistent adoption of coverage policies.

Diabetes Prevention Interventions

Extensive research has shown that adults with prediabetes can prevent or delay the onset of diabetes through intensive lifestyle change and/or the use of select medications such as metformin [14–16]. Intensive lifestyle interventions focus on the support of modest weight reduction through dietary changes and increased physical activity. The ACA included multiple provisions to stimulate healthier lifestyle behaviors leading to diabetes prevention, as well as access to, availability, and participation in individual and group programs based upon the DPP.

The ACA created the Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF), which represents a substantial investment in prevention and public health programs with the goal of improving health and reducing costs (Table 1). The PPHF provides funding for the National Diabetes Prevention Program (NDPP), a public-private initiative that offers tools and resources at both a national and state level for bolstering community and workforce capacity to deliver DPP-based lifestyle interventions [63]. The NDPP includes a Diabetes Prevention Recognition Program (DPRP), promoting standards for DPP delivery, guidelines for organizational recognition, regional workforce trainings, and a national registry of recognized organizations offering the program [63]. As of October 2015, YMCA of the USA (YUSA), currently the largest volume intervention provider recognized by NDPP, reports having offered the YMCA’s Diabetes Prevention Program to 37,710 people, via 3320 trained lifestyle coaches in more than 1370 locations in 43 states [64]. The NDPP registry lists 587 additional non-YMCA organizations delivering programs in all 50 states [63], representing tremendous growth in national capacity to reduce the burden of type 2 diabetes.

The ACA also enables access to NDPP-recognized programs through the aforementioned no-copay coverage requirements for preventive services. In August 2014, USPSTF issued a “B” recommendation that all overweight or obese adults with cardiovascular risk factors, including elevated blood glucose, be offered an intensive behavioral counseling intervention [55]. The USPSTF highlighted the DPP as a prototypical program that could be offered in either healthcare or community settings to satisfy this recommendation [65, 66]. If adopted by multiple health payers, such a provision could dramatically increase NDPP participation on a national scale.

The PPHF also partially funds the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), which sponsors two programs (DP13–1305 and DP14–1421) that have provided enhanced funding to state and/or local health departments in all 50 states and the District of Columbia for new PSE interventions targeting worksites, schools, communities, and health systems to prevent obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke [67]. Under the Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases in Medicaid Program, the ACA also legislated a funding program to enable states to test the effectiveness of providing incentives directly to Medicaid beneficiaries who participate in designated prevention programs and services. Several states, including Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, and New York, are focusing on diabetes prevention, specifically on increasing access to and enrollment in the NDPP [68].

Through these and additional initiatives summarized in Table 1, the ACA stimulated PSE at multiple levels to address diabetes prevention directly or indirectly via strategic programs targeting physical activity promotion and obesity prevention. As there has been very little reporting to date regarding the effectiveness of these initiatives, research is still needed to help understand how to improve these efforts, as well as to replicate and scale approaches that prove to be cost-effective.

Gaps

One challenge faced by many ACA provisions funded under the PPHF is the reduction or defunding of key programs. The ACA initially allocated the PPHF with $15 billion over the first 10 years, but in 2012 these funds were cut by $5 billion, and each year there have been additional debates about its funding. One repercussion of these cuts was termination of the Community Transformation Grant (CTG) program, which from 2011 to 2014 awarded $103 million to 61 state and local governments, tribes and territories, and nonprofit organizations in 36 states to help communities reduce health gaps and prevent diabetes and other chronic conditions. Until there are strong evaluations demonstrating value of PSE initiatives such as the CTG, they likely will remain vulnerable to public funding cuts.

Similar to the USPSTF diabetes screening recommendation described above, enforcement will prove to be a challenge for the USPSTF-recommended intensive lifestyle interventions for adults with prediabetes. Under the ACA, this grade B recommendation must be offered with no copay. Because the cost of an intensive intervention (median cost of about $424 per person) [69] is more than the cost of blood glucose screening (national midpoint $17.87 per hemoglobin A1c test or $7.23 per plasma glucose test) [70], it is even more likely that health payers will look for lower-cost intervention alternatives or may offer more intensive NDPP interventions as an out-of-network service that includes higher levels of cost-sharing. Until strong evaluations demonstrate that the higher cost of more intensive programs yields greater health improvements over a relatively short time horizon (3 to 5 years), full coverage of full NDPP intervention programs may continue to present a challenge [20].

While national capacity to deliver DPP-based lifestyle interventions has increased dramatically, there still are not enough programs available to meet the population demand. Delivery of DPP-based interventions using broader channels, such as via television, internet, or smartphone, will also be helpful to ensure population reach and effectiveness [71]. One encouraging step forward was the award of federal funding in 2012 to YUSA for a $12 million demonstration project to implement and evaluate offering of the YMCA’s Diabetes Prevention Program to 10,000 Medicare beneficiaries in 17 communities across the nation [72]. This initiative will provide strong evidence and, if successful, could support a national Medicare coverage decision of DPP-based interventions.

Innovation and Enhanced Care Models

If the effects of healthcare-focused diabetes prevention efforts are to reach a population level, the preventive care continuum must become part of the fabric of healthcare delivery. The ACA includes several provisions to spark innovation and redesign in healthcare delivery and payment. For example, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) was created by the ACA to “test innovative payment and service delivery models…while… enhancing the quality of care.” [27] To date, CMMI has funded a portfolio of projects focused on innovations to prevent type 2 diabetes and other chronic diseases [73]. Accountable care organizations (ACOs) are a second way the ACA sought to spur innovation in the delivery and payment for health services. ACOs are networks of healthcare providers, hospitals, and other partners who share both medical and financial responsibility for a population of patients in hopes of improving quality and decreasing costs [74]. ACOs keep a share of any savings to the Medicare system resulting from high-quality care delivered below projected costs. These financial incentives drive ACOs to develop strategies for reducing expenditures without compromising healthcare access or quality. One important strategy is population health management, which involves proactive attempts to identify individuals at high risk for health deterioration and to intervene before their health declines. There is emerging evidence that ACOs may reduce healthcare expenditures, decrease acute care utilization, and increase patient satisfaction when compared to traditional fee-for-service models [75]. To the extent that ACOs have strong incentives for preventing chronic diseases such as diabetes, these organizations may also help accelerate diabetes prevention by proactively identifying high-risk individuals and offering access to DPP-based interventions, before the development of type 2 diabetes.

Gaps

Despite the expansion of value-based funding models, only a handful of commercial payers have designed outcome-based payments for diabetes prevention services. One such approach involves a partnership between UnitedHealth Group (UHG) and YUSA, in which YMCAs receive increasing payments for health plan enrollees who achieve high YDPP attendance and/or ≥5 % weight loss. In 2013, UHG projected that (based on a cost of $400 per completer and mean participant weight loss of 5 %) health improvements could generate cost savings within 3 years [76]. A shift towards value-based payment models for diabetes prevention might be catalyzed by quality indicators for diabetes screening or for referral for evidence-based treatments. Such quality measures do not yet exist and, thus, should be considered an important area of new work for leading quality improvement organizations such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance and National Quality Forum [77, 78].

Conclusion

Successful diabetes prevention will require a concerted effort by individuals, healthcare providers, and health systems to improve awareness of diabetes risk, linkages to effective interventions, and subsequent behavioral changes. The ACA provides many opportunities to support population-based diabetes prevention. Some immediate impacts have come in the form of (1) national increases in the number and availability of evidence-based lifestyle prevention programs and (2) requirements for health payer coverage of diabetes screening tests and lifestyle interventions, which could substantially increase risk awareness and engagement of high-risk persons in cost-effective programs. More policy actions are needed to expand the availability of DPP-based intervention programs, both in overall number and via a wider array of delivery channels, and to ensure that new USPSTF recommendations for prediabetes screening and lifestyle intervention services are offered routinely by healthcare providers and incorporated into transparent health payer coverage policies. Similarly, it will be important to conduct research that evaluates the impact of broader policy actions on diabetes prevention. One example is whether health delivery system and payment reforms designed to promote chronic disease prevention, care coordination, and population health management can have a specific impact on diabetes prevention. Another example involves efforts to raise public awareness about diabetes prevention, obesity, or its risk factors. For instance, the CDC, AMA, ADA, and the Ad Council recently announced a partnership to launch a first-of-its-kind PSA campaign encouraging individuals to know their risk for diabetes and make lifestyle changes [79]. On a broader scale, the First Lady’s “Let’s Move” initiative aims to raise public awareness and mobilize policy action across sectors to solve the problem of childhood obesity [80]. As this work continues to unfold, ongoing research of the impact of policies and programs on diabetes prevention will be needed to identify and preserve the most successful policies and to ensure that diabetes prevention reaches all segments of the American population equitably.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health (K23 DK095981, O’Brien), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR001422, Ackermann).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest Namratha Kandula discloses that she receives salary support from the American Medical Association and honoraria from Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute for serving as a grant reviewer. Juleigh Nowinski Konchak, Margaret Moran, Matthew O’Brien, and Ronald Ackermann declare that they have nothing to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed May 3, 2014];National Diabetes Statistical Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/ statsreport14.htm.

- 2.Menke A, Casagrande S, Geiss L, Cowie CC. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among adults in the United States, 1988–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1021–1029. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler NE, Prather AA. Risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus: person, place, and precision prevention. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1321–1322. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christine PJ, Auchincloss AH, Bertoni AG, et al. Longitudinal associations between neighborhood physical and social environments and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1311–1320. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ackermann RT, Kenrik Duru O, Albu JB, et al. Evaluating diabetes health policies using natural experiments: the natural experiments for translation in diabetes study. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(6):747–754. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Luke DA. Shaping the context of health: a review of environmental and policy approaches in the prevention of chronic diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:341–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu FB, Satija A, Manson JE. Curbing the diabetes pandemic: the need for global policy solutions. JAMA. 2015;313(23):2319–2320. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herman WH, Hoerger TJ, Brandle M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification or metformin in preventing type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(5):323–332. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00007. PMCID 2701392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selvin E, Steffes MW, Gregg E, Brancati FL, Coresh J. Performance of A1C for the classification and prediction of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):84–89. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1235. PMCID 3005486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1884–1890. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillett M, Royle P, Snaith A, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions to reduce the risk of diabetes in people with impaired glucose regulation: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(33):1–236. doi: 10.3310/hta16330. iii-iv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillies CL, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, et al. Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;334(7588):299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39063.689375.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens JW, Khunti K, Harvey R, et al. Preventing the progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults at high risk: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of lifestyle, pharmacological and surgical interventions. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107(3):320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuen A, Sugeng Y, Weiland TJ, Jelinek GA. Lifestyle and medication interventions for the prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus in prediabetes: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. AustNZ J Public Health. 2010;34(2):172–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali MK, Echouffo-Tcheugui J, Williamson DF. How effective were lifestyle interventions in real-world settings that were modeled on the Diabetes Prevention Program? Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(1):67–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Florez H, Pan Q, Ackermann RT, et al. Impact of lifestyle intervention and metformin on health-related quality of life: the diabetes prevention program randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1594–1601. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2122-5. PMCID PMC3509296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratner R, Goldberg R, Haffner S, et al. Impact of intensive lifestyle and metformin therapy on cardiovascular disease risk factors in the diabetes prevention program. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(4):888–894. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ackermann RT, Marrero DG, Hicks KA, et al. An evaluation of cost sharing to finance a diet and physical activity intervention to prevent diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1237–1241. doi: 10.2337/dc05-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhuo X, Zhang P, Gregg EW, et al. A nationwide community-based lifestyle program could delay or prevent type 2 diabetes cases and save $5.7 billion in 25 years. Health Aff (Mllwood) 2012;31(1):50–60. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1677–1686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. PMCID 3135022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ackermann RT. Research to inform policy in diabetes prevention: a work in progress. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(2):225–227. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackermann RT, Liss DT, Finch EA, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness trial for preventing type 2 diabetes. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2328–2334. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302641. This study demonstrated meaningful weight loss with a community-based Diabetes Prevention Program

- 25.Deshpande AD, Dodson EA, Gorman I, Brownson RC. Physical activity and diabetes: opportunities for prevention through policy. Phys Ther. 2008;88(11):1425–1435. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20080031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matson-Koffman DM, Brownstein JN, Neiner JA, Greaney ML. A site-specific literature review of policy and environmental interventions that promote physical activity and nutrition for cardiovascular health: what works? Am J Health Promot. 2005;19(3):167–193. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.3.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. America SaHoRotUSo, ed. Public Law. Washington, D.C: 2010. pp. 111–148. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cogan JA., Jr The Affordable Care Act’s preventive services mandate: breaking down the barriers to nationwide access to preventive services. J Law Med Ethics. 2011;39(3):355–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaffe S. Diabetes, obesity, and the Affordable Care Act. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(7):543. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thorpe KE. Analysis & commentary: The Affordable Care Act lays the groundwork for a national diabetes prevention and treatment strategy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(1):61–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins ST. Borrowing from tobacco control to curtail the overweight and obesity epidemic: leveraging the U.S. Surgeon General’s Report. Prev Med. 2015;80:47–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.12.021. PMCID 4490146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preston CM, Alexander M. Prevention in the United States Affordable Care Act. J Prev Med Public Health. 2010;43(6):455–458. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2010.43.6.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gregg EW, Ali MK, Moore BA, et al. The importance of natural experiments in diabetes prevention and control and the need for better health policy research. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E14. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120145. PMCID PMC3562225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Majumdar SR, Soumerai SB. The unhealthy state of health policy research. Health Aff (Mllwood) 2009;28(5):w900–W908. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Mujahid MS, Shen M, Bertoni AG, Carnethon MR. Neighborhood resources for physical activity and healthy foods and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Multi-Ethnic study of Atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(18):1698–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.302. PMCID PMC2828356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes—a randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(16):1509–1519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1103216. PMCID PMC3410541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee on Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention, Glickman D. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: solving the weight of the nation. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:S8–S16. doi: 10.2337/dc15-S005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Monitoring Access to Personal Health Care Services., Millman ML. Access to health care in America. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Department of Health and Human Services. Health insurance coverage and the Affordable Care Act. In: OotASfPaE ASPE, editor. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins SR, Rasmussen PW, Doty MM, Beutel S. Commonwealth Fund. Washington, DC: 2015. The rise in health care coverage and affordability since health reform took effect. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaufman HW, Chen Z, Fonseca VA, McPhaul MJ. Surge in newly identified diabetes among Medicaid patients in 2014 within Medicaid expansion states under the Affordable Care Act. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(5):833–837. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2334. This study compares states that implemented expanded Medicaid with those that did not, assessing the effect on diagnosis of diabetes

- 43.Baicker K, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al. The Oregon experiment— effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212321. PMCID 3701298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cassidy A. Health policy brief: preventive services without cost sharing. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: the chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1909–1914. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dietz WH, Solomon LS, Pronk N, et al. An integrated framework for the prevention and treatment of obesity and its related chronic diseases. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(9):1456–1463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wozniak L, Soprovich A, Rees S, Al Sayah F, Majumdar SR, Johnson JA. Contextualizing the effectiveness of a collaborative care model for primary care patients with diabetes and depression (Teamcare): a qualitative assessment using RE-AIM. Can J Diabetes. 2015;39(Suppl 3):S83–S91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mangione CM, Gerzoff RB, Williamson DF, et al. The association between quality of care and the intensity of diabetes disease management programs. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(2):107–116. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-2-200607180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsai AC, Morton SC, Mangione CM, Keeler EB. A meta-analysis of interventions to improve care for chronic illnesses. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(8):478–488. PMCID PMC3244301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, et al. Improving patient care. The patient centered medical home. A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):169–178. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herman WH, Cefalu WT. Health policy and diabetes care: is it time to put politics aside? Diabetes Care. 2015;38(5):743–745. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang X, Geiss LS, Cheng YJ, Beckles GL, Gregg EW, Kahn HS. The missed patient with diabetes: how access to health care affects the detection of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(9):1748–1753. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0572. PMCID PMC2518339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Geiss LS, James C, Gregg EW, Albright A, Williamson DF, Cowie CC. Diabetes risk reduction behaviors among U.S. adults with prediabetes. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siu AL. Screening for Abnormal Blood Glucose and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2015 doi: 10.7326/M15-2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bullard KM, Saydah SH, Imperatore G, et al. Secular changes in U.S. Prediabetes prevalence defined by hemoglobin A1c and fasting plasma glucose: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1999–2010. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2286–2293. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2563. PMCID 3714534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ali MK, Bullard KM, Saaddine JB, Cowie CC, Imperatore G, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in U.S. diabetes care, 1999–2010. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1613–1624. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1213829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.American Medical Association. [Accessed March 13, 2015];Prevent Diabetes STAT. 2015 www.preventdiabetesstat.org.

- 59.National Diabetes Education Program: Diabetes Management & Prevention Resources for Health Care Professionals. [Accessed October 3, 2015]; http://www.ndep.nih.gov/hcp-businesses-and-schools/HealthCareProfessionals.aspx.

- 60.Health plan implementation of U.S. Preventive Services Task Force A and B recommendations—Colorado, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(39):1348–1350. This article provides a more in depth study of some of the challenges to systematic and universal implementation of the USPSTF coverage requirements under the ACA

- 61.Kofman M, Dunton K, Senkewicz MB. Implementation of tobacco cessation coverage under the Affordable Care Act: understanding how private health insurance policies cover tobacco cessation treatments. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Health Policy Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed October 12, 2015];Preventive Services Covered by Private Health Plans under the Affordable Care Act. 2015 http://kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/preventive-services-covered-by-private-health-plans/

- 63.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed February 7, 2012];National Diabetes Prevention Program. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/index.htm.

- 64.YMCA. [Accessed October 22, 2015];Measurable Progress, Unlimited Support: Diabetes Prevention Program Fact Sheet: October 2015. 2015 http://www.ymca.net/diabetes-prevention.

- 65.LeFevre ML. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):587–593. doi: 10.7326/M14-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin JS, O’Connor E, Evans CV, Senger CA, Rowland MG, Groom HC. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthy lifestyle in persons with cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(8):568–578. doi: 10.7326/M14-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed September 23, 2015];Programs: Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/programs.htm.

- 68.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed October 3, 2015];Medicaid Incentives for Prevention of Chronic Diseases Grants. 2011 https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2011 -Fact-sheets-items/2011-09-13.html.

- 69.Li R, Qu S, Zhang P, et al. Economic evaluation of combined diet and physical activity promotion programs to prevent type 2 diabetes among persons at increased risk: a systematic review for the community Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):452–460. doi: 10.7326/M15-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed January 28, 2016];Clinical Laboratory Fee Schedule, 2016. 2016 https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/clinicallabfeesched/clinlab.html.

- 71.Ackermann RT, Sandy LG, Beauregard T, Coblitz M, Norton KL, Vojta D. A randomized comparative effectiveness trial of using cable television to deliver diabetes prevention programming. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22(7):1601–1607. doi: 10.1002/oby.20762. PMCID PMC4238734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.YMCA; The Y Receives Innovation Grant to Test Cost Effectiveness of Diabetes Prevention Program Among Medicare Population. [Accessed October 7, 2015]; http://www.ymca.net/news-releases/20120618-innovation-grant.html.

- 73.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed October 7, 2015];Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (The CMS Innovation Center) 2015 https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/index.html#views=models.

- 74.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed October 8, 2015];Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs): General Information. 2015 https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/ACO/

- 75.Nyweide DJ, Lee W, Cuerdon TT, et al. Association of Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations vs traditional Medicare fee for service with spending, utilization, and patient experience. JAMA. 2015;313(21):2152–2161. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vojta D, Koehler TB, Longjohn M, Lever JA, Caputo NF. A coordinated national model for diabetes prevention: linking health systems to an evidence-based community program. Am J Prev Med. 2013;444(Suppl 4):S301–S306. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.National Committee for Quality Assurance. [Accessed October 8, 2015];HEDIS & Quality Measurement. 2015 http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement/HEDISMeasures.aspx.

- 78.National Quality Forum. [Accessed October 8, 2015];Measures, Reports, & Tools. 2015 http://www.qualityforum.org/Measures_Reports_Tools.aspx.

- 79.First-of-its-Kind PSA Campaign Targets the 86 Million American Adults with Prediabetes [press release] Atlanta, GA USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Jan 21, [Google Scholar]

- 80.LetsMove.Gov. Let’s Move: America’s Move to Raise a Healthier Generation of Kids. [Accessed January 27, 2016]; http://www.letsmove.gov/

- 81.National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO) [Accessed September 14, 2015];Public health and prevention provisions of the affordable care act. http://www.naccho.org/advocacy/upload/PH-and-Prevention-Provisions-in-the-ACA-Revised.pdf.

- 82.Trust for America’s Health. [Accessed September 14, 2015];Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (HR 3590) selected prevention, public health, and workforce provisions. http://healthyamericans.org/assets/files/Summary.pdf.

- 83.Obamacare Facts. [Accessed September 14, 2015];Summary of provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. http://obamacarefacts.com/summary-of-provisions-patient-protection-and-affordable-care-act/