Abstract

The collagen VI-related myopathy known as Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy is an early-onset disease that combines substantial muscle weakness with striking joint laxity and progressive contractures. Patients might learn to walk in early childhood; however, this ability is subsequently lost, concomitant with the development of frequent nocturnal respiratory failure. Patients with intermediate phenotypes of collagen VI-related myopathy display a lesser degree of weakness and a longer period of ambulation than do individuals with Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy, and the spectrum of disease finally encompasses mild Bethlem myopathy, in which ambulation persists into adulthood. Dominant and recessive autosomal mutations in the three major collagen VI genes—COL6A1, COL6A2, and COL6A3—can underlie this entire clinical spectrum, and result in deficient or dysfunctional microfibrillar collagen VI in the extracellular matrix of muscle and other connective tissues, such as skin and tendons. The potential effects on muscle include progressive dystrophic changes, fibrosis and evidence for increased apoptosis, which potentially open avenues for pharmacological intervention. Optimized respiratory management, including noninvasive nocturnal ventilation together with careful orthopedic management, are the current mainstays of treatment and have already led to a considerable improvement in life expectancy for children with Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy.

Introduction

The collagen VI-related myopathies encompass a spectrum of disease ranging from severe Ullrich muscular dystrophy to mild Bethlem myopathy. These diseases are caused by mutations in the genes that encode the three major α-chains of collagen type VI. They are unique among the hereditary myopathies in that they are hybrid disorders with clinical features attributable to both muscle and connective tissue. As such, they are paradigmatic disorders of the ‘myomatrix’—the extracellular matrix of muscle—and highlight the importance of the myomatrix in the functioning and maintenance of muscle.

Although precise prevalence data are lacking, Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) is probably the most common type of CMD encountered in the North American population, and is the second most common form (after Fukuyama CMD) in the Japanese population.1 In northern England, the prevalence of Ullrich CMD is 0.13 cases per 100,000 of the population, and that of Bethlem myopathy is 0.77 cases per 100,000.2 In a study based purely on immunohistochemistry, collagen VI-related disorders were the second most frequently identified form of CMD after the α-dystroglycanopathies.3

This Review will provide a succinct clinical picture of this distinct group of conditions, and highlight their physiological basis, current management and potential new avenues for treatment.

The clinical spectrum of disease

On the basis of clinical as well as genetic findings, Ullrich CMD and Bethlem myopathy can justifiably be regarded as being positioned at the flanking ends of a continuous spectrum of disease, rather than as distinct clinical entities.

Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy

Presentation

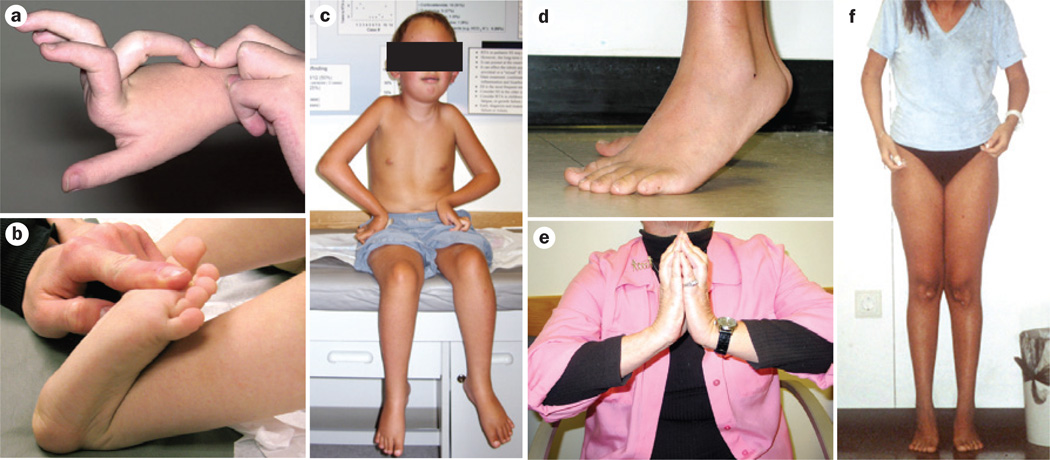

Prenatal movements might be reduced in fetuses with Ullrich CMD;4–10 however, the classic phenotype described by Ullrich4,5 (Box 1) is usually evident at birth. Symptoms such as hypotonia and weakness are present, with striking hyperlaxity in particular of the distal joints (Figure 1a,b). The hands and fingers are extremely flexible and can bend backwards against the forearm, while the feet are often bent backwards against the shin, a finding that parents often remember as one of the first signs noticed. Coexisting joint contractures might also be evident at birth, affecting the elbows, knees, spine (kyphoscoliosis) and neck (torticollis). Clubfoot can also be seen, instead of the retroflexed foot mentioned above.

Box 1. History of the collagen VI-related myopathies.

In the early 1930s, Otto Ullrich described a unique group of pediatric patients with a new condition, which he termed scleratonic muscular dystrophy (Skleratonische Muskeldystrophie). The notable feature of this disease was the coexistence of prominent early-onset weakness and joint laxity with severe and progressive contractures in the proximal joints.4,5 Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) was initially discussed largely in the Japanese and German literature,6–8 although a few articles were published in English-language journals.

In 1977, Jaap Bethlem and George K. van Wijngaarden described three families with dominant transmission of a benign myopathy characterized by slow progression and prominent contractures.106 Additional families with Bethlem myopathy were then identified, which emphasized the typical clinical features of early onset and a mild course, despite progression into adulthood.107 Several research groups identified linkage of this disease to chromosomes 2 and 21, which subsequently led to the identification of causative mutations in the COL6A1, COL6A2 and COL6A3 genes.94,108,109 Bethlem myopathy was, therefore, established as the first collagen VI-related myopathy.94,108,109

In 2002, Enrico Bertini, Mimma Pepe and colleagues recognized the similarities in clinical features between patients with Bethlem myopathy and those with Ullrich CMD. These researchers analyzed muscle biopsy samples from patients with Ullrich CMD, and identified three patients with a complete absence of collagen VI associated with recessive null mutations in COL6A2.83 The identification of collagen VI mutations as the underlying cause of both Ullrich CMD and Bethlem myopathy led to renewed international interest in these disorders.

Figure 1.

Joint laxity and progressive joint contractures in patients with Ullrich CMD and Bethlem myopathy. a,b | Typical pronounced distal hyperlaxity seen in children with Ullrich CMD, particularly in the fingers. c | A patient with typical Ullrich CMD who had an initial period of ambulation but can no longer walk—note evolving contractures in the shoulders, elbows and knees, round face with mild facial erythema, as well as distal joint laxity. d | Pronounced Achilles tendon contractures in a teenager with Bethlem myopathy. e | Typical long finger flexor contractures in an adult patient with Bethlem myopathy prevent full extension of the fingers when the palms are placed together with dorsiflexed hands and elevated elbows (the ‘Bethlem sign’). f | An adult with Bethlem myopathy. The typical upper body posture results from contractures at the elbows and shoulders. She also has contractures of the Achilles tendons. Abbreviation: CMD, congenital muscular dystrophy. Written consent for publication was obtained from the father of the patient featured in part c.

Course of disease

Some transient feeding difficulties might occur in the neonatal period, leading to moderate to severe dysphagia in patients with severe forms of Ullrich CMD.11 Even some children without overt dysphagia may need a temporary or permanent gastric feeding tube support to maintain an adequate nutritional and fluid intake.

In the most severe presentation of Ullrich CMD, the ability to walk is never achieved. Patients with this presentation were referred to as having ‘early severe’ disease in a large French series of early-onset collagen VI-related myopathies.12 However, even these severely affected infants can usually learn to roll, crawl and maintain a sitting position. Some severely affected children who are not able to ambulate owing to knee contractures that prevent an upright posture might walk on their knees for a period of time. The majority of patients with typical Ullrich CMD will, however, achieve the ability to ambulate after a delay of up to about 2 years. This group was referred to as having ‘moderately progressive’ disease in the French series (Box 2).12 These children will, however, eventually lose the ability to walk, often by the early teenage years, but sometimes at a considerably younger age or as late as young adulthood (Figure 1c).11,12

Box 2. Spectrum of collagen VI-related myopathy phenotypes.

Severe Ullrich CMD (early severe*)

Patient achieves sitting, sometimes knee walking, but not independent ambulation, frequently severe contractures.

Typical Ullrich CMD (moderate progressive*)

Patient achieves independent ambulation, albeit after some delay, but loses this ability again by age 20 years; ambulation is typically lost by age 5–15 years, frequently severe contractures.

Intermediate phenotype (mild*)

Ambulation beyond 20 years into young adulthood, contractures more variable.

Bethlem myopathy

Typical Bethlem myopathy: ambulation into adulthood

-

■

Myosclerosis variant: the degree of contractures by far outweighs weakness; ‘woody’ feel to the muscles

-

■

Collagen VI-related limb-girdle syndrome: juvenile or young adult onset, weakness in a proximal distribution with only minimal, if any contractures

*The descriptions represent the phenotype classifications suggested for the Ullrich CMD to intermediate-severity spectrum of early-onset collagen VI-related myopathy.12 Abbreviation: CMD, congenital muscular dystrophy.

The muscle weakness itself is slowly progressive, but the resulting disability is aggravated by progressive contractures of the large joints, in particular affecting external rotation in the shoulder, elbows, hips, knees and ankles. Some early contractures can improve during the first year of life, but will recur at a later point and then continue to worsen over time. The presence of multiple lower extremity contractures, in particular, interferes with the ability to ambulate. After the loss of ambulation, patients tend to be quite stable in terms of their muscular strength, although the contractures might still show ongoing progression, particularly in the ankles, knees, hips and elbows. Of particular concern is the development of substantial scoliosis, which might have developed as early as the preschool years, but is frequently evident by the end of the first decade of life and requires spinal instrumentation in many patients.11,12

Although respiratory insufficiency is not common at birth, it becomes an important aspect of the disease as the condition progresses. Respiratory insufficiency usually manifests following the loss of ambulation, but some patients can develop impending respiratory insufficiency while they still have the ability to walk.11 A progressive decline in the percentage of predicted forced vital capacity is observed, on average, from the age of 5 years to the early teens.11 Respiratory insufficiency typically manifests initially at night, as nocturnal hypoxemia, and sleep studies may be necessary to identify its first signs. The introduction of noninvasive bilevel positive airway pressure ventilation is usually sufficient to treat this situation effectively for many years. In most patients respiratory support is only needed at night; however, it should not be overlooked. Failure to institute adequate respiratory support has led to the death of teenagers with Ullrich CMD.

Careful studies are now required to establish the long-term course of the disease under the current standards of medical care. Early data on the long-term outcomes of patients with Ullrich CMD are difficult to evaluate, as much of that experience was gathered from patients who had not received active respiratory intervention, with the result that many of these individuals succumbed to respiratory failure in their late teenage years.7 With the availability of effective respiratory interventions, other aspects of the disease could potentially surface now that patients with Ullrich CMD routinely survive into adulthood.

Intermediate collagen VI-related myopathies

Presentation

Patients with collagen VI-related myopathies of intermediate severity cannot be easily classified as having either Ullrich CMD or Bethlem myopathy. No exact definitions exist yet as to where the Ullrich CMD phenotype stops and the intermediate-severity phenotype begins. Similarly, at the other end of the range, a transition from intermediate-severity disease to the classic Bethlem phenotype occurs. To define this disease spectrum, and to determine whether discrimination between the various phenotypes is possible, an international study capturing the range of phenotypic expression in patients with collagen VI-related myopathies is currently underway.

Patients with intermediate phenotypes of collagen VI-related myopathies were referred to as having ‘mild’ early-onset collagen VI myopathy in the French series.12 Similarly to children with Ullrich CMD, these patients also typically present in the neonatal period but achieve the ability to walk, usually ambulating into young adulthood and sometimes beyond. They are, therefore, considered to have a milder form of disease than patients with the typical Ullrich CMD phenotype. However, most of the clinical features outlined for Ullrich CMD will still be clearly recognizable in these patients.

Course of disease

Although contractures are not necessarily prominent early on in intermediate-severity disease, they start to develop during childhood and are progressive, particularly in the ankles and the elbows, but also in the knees. Scoliosis and/or spinal rigidity can be marked. Patients might be able to walk for limited distances, particularly on flat surfaces and indoors, but they may require assistance such as a mobility scooter for prolonged ambulation. However, spending increased amounts of time in the sitting position will aggravate contractures of the knee flexors and the hips, and further interfere with the patient’s ability to walk. Upright mobility should, therefore, be maximized for as long as possible.

Progressive respiratory insufficiency is also of concern in patients with intermediate phenotypes of collagen VI-related myopathy, and a consistent decline in the percentage of predicted forced vital capacity is observed in the early teenage years.11 This group of patients is again particularly susceptible to nocturnal respiratory insufficiency, which can develop even in individuals who are still able to walk and, therefore, careful monitoring of these patients is required.11

Bethlem myopathy

Presentation

Considerable variability exists within the Bethlem myopathy phenotype. Many of the same clinical problems described for the other forms of collagen VI-related myopathy can be encountered in principle, but the symptoms are altogether milder. Although often understood to be a myopathy of adulthood, the clinical symptoms experienced by patients with Bethlem myopathy can frequently be traced back to early infancy;13 affected babies might exhibit hypotonia, foot deformities and torticollis (which has been noted in up to 50% of patients).13 However, the congenital contractures largely tend to resolve in the first 2 years. Young children might exhibit evidence of mild weakness only, and at this early age display distal joint hyperlaxity rather than contractures. Some patients present with weakness in a proximal distribution without notable contractures and have been reported as limb-girdle muscular dystrophy.14 By contrast, others have contracture-predominant disease without much weakness, a phenotype referred to as myosclerosis.15,16 In such individuals, the muscles are said to have a ‘woody’ feel. A specific recessive mutation has been associated with this phenotype, as discussed later in this article.

Course of disease

In Bethlem myopathy, typical contractures of the Achilles tendons (Figure 1d) and elbows tend to develop late in the first decade of life and during teenage years. These contractures progress to involve the long finger flexors and the shoulders; they can also affect the spine and cause a degree of spinal rigidity in some patients. On dorsiflexion of the wrist, contractures of the long finger flexors prevent complete finger extension—the typical ‘Bethlem sign’ (Figure 1e).13 Even in patients whose muscle weakness progresses only very slowly, progression of the contractures can be the cause of serious disability in their own right (as they are for patients with severe forms of collagen VI-related myopathy). Eventually, the combination of weakness and contractures can lead to walking difficulties—about two-thirds of patients over the age of 50 years require help with ambulation, usually using a mobility scooter or wheelchair.13 Patients with Bethlem myopathy who had been stable for many years often report a noticeable decline in muscle strength in their 4th and 5th decades of life (Figure 1f).

Patients with Bethlem myopathy have an increased risk of restrictive lung disease, with the possibility of resulting respiratory insufficiency, particularly if this impairment occurs in combination with other causes of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep studies are, therefore, useful to diagnose nocturnal hypoventilation proactively.

Diagnosis

Clinical diagnostic features

Connective tissue involvement

A common feature across the entire spectrum of collagen VI-related myopathies is the prominent and clinically evident involvement of connective tissue.17 This characteristic assists the clinical diagnosis as well as substantially adding to the patient’s disability.

Evidence from research in a mouse model of collagen VI deficiency indicates that this condition is associated with morphological abnormalities of the tendons (M.-L. Chu et al., personal communication). These results indicate the presence of a tendinopathy that probably contributes both to the laxity of small joints and to the contractures. Further analysis could reveal whether patients display additional symptoms or signs relating to altered collagen VI expression in other extracellular matrices, such as the lens, intervertebral discs, joints and vessels. For instance, analysis of mice with collagen VI deficiency has revealed an increased propensity for osteoarthritic joint degeneration.18

Skin involvement

A characteristic skin phenotype is associated with collagen VI-related myopathy. The most notable manifestations are prominent keratosis pilaris of the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, giving the skin a rough appearance, the propensity for abnormal (keloid or atrophic) scar formation, and/or a particularly soft and velvety texture to the palmar skin of the hands and feet, which are marked by a fine criss-cross pattern of palmar creases. The latter skin features are not specific for collagen VI-related myopathy, as they are also seen in patients with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.19

Differential diagnosis

Depending on the age of the patient and the leading clinical features, a number of considerations are relevant in the differential diagnosis of collagen VI-related myopathy.

Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy

Some patients with Bethlem myopathy present with weakness in a proximal distribution without notable contractures, which can resemble limb-girdle muscular dystrophy.14 Bethlem myopathy might, therefore, need to be considered as a differential diagnosis in patients whose clinical features suggest limb-girdle muscular dystrophy. The use of muscle imaging (see below) is most helpful in this situation by recognizing a Bethlem-typical pattern of muscle involvement.

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

In the young child with moderate to severe weakness and notable joint laxity, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome needs to be considered, particularly the type VI (kyphoscoliotic) form.20 The hypermobile type of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, which results from tenascin X deficiency, should be considered, particularly in teenage and adult patients with notable hyperlaxity.21 In these patients, however, the associated muscle weakness and contractures will be milder than in Bethlem myopathy. In addition, in tenascin X deficiency there is hyperelasticity of the skin, which is not seen in the collagen VI-related myopathies. Interestingly, ultrastructural examination of skin biopsies from patients with Ullrich CMD show abnormal structures for the large fibrillar collagens as well as abnormal deposition of elastic fibers, which resemble some of the findings seen in classic Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.19 Abnormal fibrillogenesis of the large fibrillar collagens, therefore, probably underlies the clinical similarities between these two diseases, consistent with a role for collagen VI in collagen fibrillogenesis.22,23

Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy

In patients with a contracture-predominant phenotype, the Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophies (which result from LMNA, EMD and FHL1 mutations) should be considered in the differential diagnosis, particularly as the patterns of contractures caused by these two conditions are very similar. The presence of cardiac involvement clearly favors the presence of an Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, as primary cardiac involvement is not seen in the collagen VI-related myopathies. Mutations in the LMNA gene might present as CMD;24 however, the pattern of weakness and contractures in LMNA-related CMD is sufficiently different from that in collagen VI-related myopathies to enable its clinical differentiation, as patients with LMNA-related CMD show very early rigidity of the spine and striking weakness of the neck, but very little knee or elbow contracture, and only moderate laxity.

Central core disease and fiber type disproportion

Secondary changes that might be seen in muscle biopsy samples from patients with collagen VI-related myopathies include minicore-like lesions resembling those in patients with RYR1-associated multiminicore disease. Fiber type disproportion, resembling the pathological diagnosis of congenital fiber type disproportion, is sometimes observed in biopsy samples taken very early in the course of collagen VI-related myopathies. These lesions can be a source of confusion and misdiagnosis in the histopathological assessment of a biopsy from a patient with a collagen VI-related myopathy, especially as some patients with particular recessive RYR1 mutations and minicores in their biopsy samples might also present with notable laxity, albeit not quite to the extent that is typical for a young patient with a collagen VI-related myopathy.25–27

Laboratory and imaging findings

The findings in muscle biopsy specimens from patients with collagen VI-related myopathies are quite variable and change over time. In samples from patients in more-advanced stages of the disease, overtly dystrophic features are evident, including rare degenerating and regenerating fibers and a prominent build-up of interstitial fibrous tissue in the muscle. In biopsy samples taken very early in the course of disease, however, the findings can be inconspicuous, often just showing evidence of fiber atrophy or even fiber type disproportion without overt dystrophic features.28

Immunohistochemical examination for the amount and localization of collagen VI in the muscle is a useful diagnostic tool. In individuals with recessive null mutations, this analysis will reveal a virtually complete absence of collagen VI in the muscle.29 In patients with dominant mutations in particular, muscle immunohistochemistry will show a considerable amount of collagen VI immunoreactivity in the extracellular matrix, but the normal localization of collagen VI in the basement membrane is lost. This loss can be highlighted if double staining with a basement membrane marker is used (Figure 2).30,31 This observation also suggests that the immunoreactivity visible in the matrix in muscle samples from these patients does not represent functionally normal collagen VI and that the mutant protein is not able to establish a normally interactive microfibrillar network.

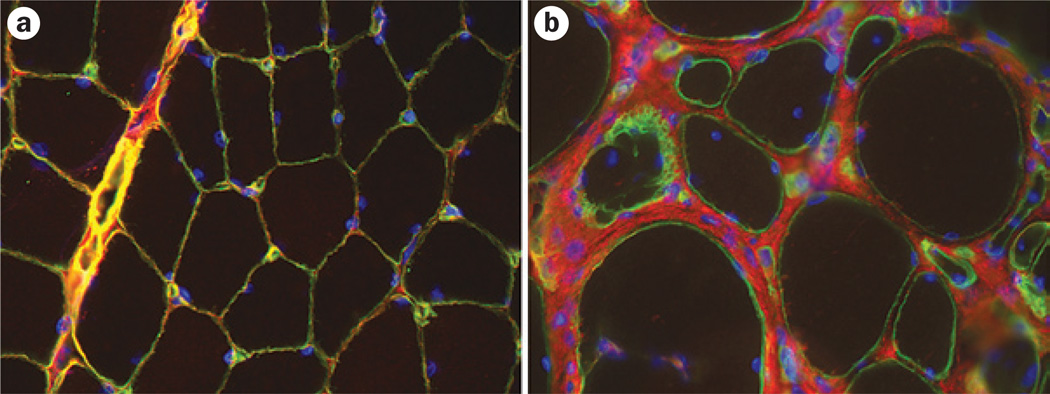

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical identification of collagen VI in the muscle. Images showing dual immunohistochemical labeling for collagen VI (red) and the basement marker laminin subunit γ-1 (green). a | Note the colocalization of collagen VI and laminin γ-1 in the basement membrane in a healthy individual, which results in a yellow color. b | In a patient with collagen VI-related myopathy, a gap is evident between the collagen VI staining and the basement membrane staining. This patient has a dominant-negative mutation, so that altered collagen VI can be excreted into the matrix but is then not able to function or interact properly.

Cultures of dermal fibroblasts from patients with collagen VI mutations often display changes of the collagen VI matrix, ranging from absence to abnormal formation. This analysis, therefore, is also a useful diagnostic tool (Figure 2).30,32–34

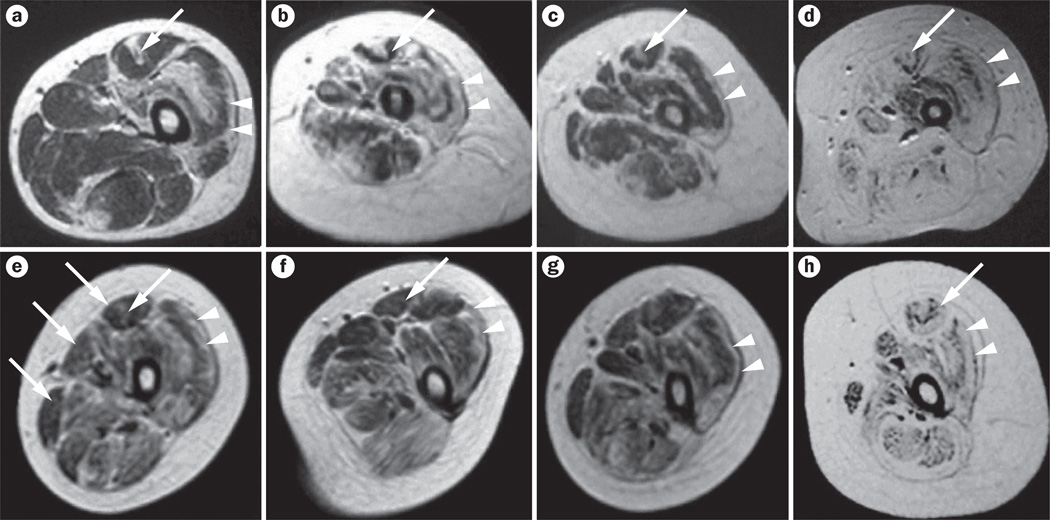

MRI of muscle can be very useful in the recognition of a collagen VI-related myopathy and in the differentiation of collagen VI-related myopathies from LMNA-related Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, as well as from other myopathies associated with contractures and spinal rigidity.35,36 In the collagen VI-related myopathies, a characteristic concentric pattern of imaging changes is observed, in that the initial degenerative changes seen on imaging are most evident on the outer aspects of the muscle, rather than the inside (Figure 3). In the rectus femoris, however, a typical central zone of altered signal is seen, originating around the central fascia that extends into this muscle.37 This phenomenon is also clearly seen on ultrasonography and has been designated a ‘central cloud’.38 This pattern is not seen in LMNA-related Emery–Dreifuss myopathy, although prominent involvement of the posterior thigh muscles and the medial gastrocnemius can be observed.35,36 However, these characteristic imaging findings in collagen VI-related myopathies may become less obvious as the disease progresses.37

Figure 3.

Muscle MRI findings in patients with collagen VI-related myopathies. T1-weighted MRI scans of the thigh in patients with a–d | Bethlem myopathy and e–h | Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy of variable severity. Characteristic fatty degeneration (white areas) is seen along the fascia in the center of the rectus femoris (long arrows) and along the rim of the vastus lateralis (arrowheads)—the characteristic ‘outside-in’ pattern. The findings in parts d and h are still visible in the patients with severe forms of these diseases. Permission obtained from Elsevier Ltd © Mercuri, E. Neuromuscul. Disord. 15, 303–310 (2005).

Properties of collagen VI

Assembly and tissue distribution

Collagen type VI, along with the fibrillins, is one of the microfibrillar components of the extracellular matrix. Collagen VI microfibrils are found in a wide variety of extracellular matrices, including muscle, skin, tendon, cartilage, intervertebral discs, lens, internal organs and blood vessels. These microfibrils show a particular association with basement membranes,39,40 and favor a pericellular distribution around cells without basement membranes, such as tendon fibroblasts.41

Three major collagen VI genes have been identified—COL6A1, COL6A2 and COL6A3. COL6A1 and COL6A2 lie in a head-to-head arrangement on chromosome 21, whereas COL6A3 is on chromosome 2.42 Three additional genes have been identified by comparative analysis as being related to COL6A3;43,44 in mice all three genes, Col6a4, Col6a5 and Col6a6, are expressed, whereas in humans COL6A4 is interrupted by a translocation and is no longer fully functional. The tissue distribution of the collagen α5(VI) chain and collagen α6(VI) chain proteins is more limited than that of the original three chains.45

The peptides encoded by COL6A1 and COL6A2 consist of short α-chain domains flanked by N-terminal and C-terminal globular domains of about equal size.46 The product of COL6A3 contains a similar-sized α-chain domain; however, its N-terminal globular domain is much larger compared with COL6A1 and COL6A2, and is alternatively spliced. The C-terminal domain of the COL6A3 transcript is proteolytically processed once secreted into the extracellular matrix as part of the assembled collagen VI (Figure 4).47

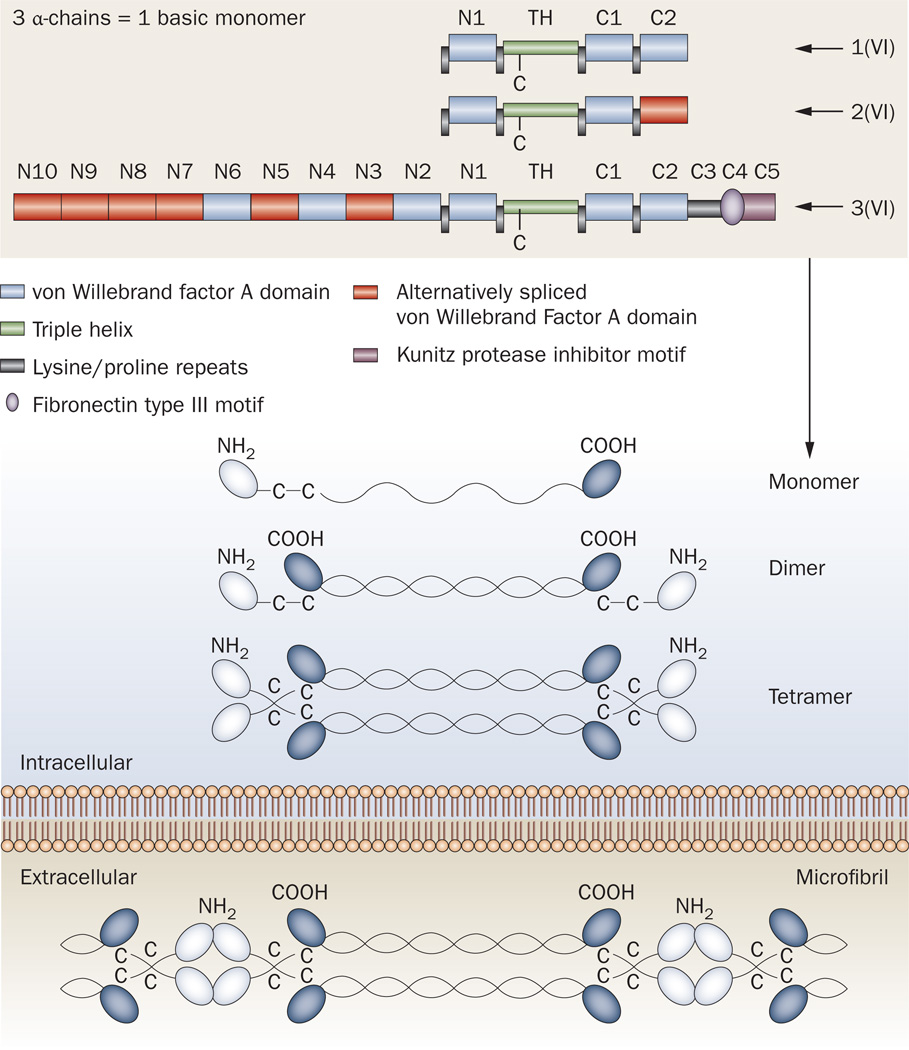

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the domains and organization of collagen VI. One of each of the three α-chains (α1, α2 and α3) combine along their collagenous triple-helical domains to form the collagen VI monomer. Within the cell, these monomers associate to form dimers, which pair up into tetramers. These tetramers are then secreted into the extracellular matrix, where they assemble by interacting at the globular domains to form the microfibrillar structures typical of collagen VI. Abbreviations: C1–C5, C-terminal globular domains 105; N1–N10, N-terminal globular domains 1–10; TH, triple-helical domain. Modified after Lampe and Bushby (2005)10 and Furthmayr et al. (1983).49

Collagen VI undergoes an extensive assembly process in the cell before being secreted into the extracellular matrix.42,48 A basic understanding of this assembly process is important to comprehend the consequences of the various disease-causing mutations. The assembly begins with the formation of the basic monomer, which is composed of one of each of the three α-chain subunits encoded by COL6A1, COL6A2 and COL6A3. Similarly to other collagens, the three α-chains first associate at their C1-terminal globular domains and come to lie adjacent to each other. Hydrogen bonding then links the three α-chains in a zipper-like fashion from the C-terminal to the N-terminal end, resulting in a triple-helical structure (Figure 4).

The next assembly step involves the formation of an antiparallel dimer, stabilized by disulfide bridging between crucial cysteines in the N-terminal ends of the triple-helical domain and in the globular domain.49–51 Two such dimers then associate in a staggered parallel orientation to form a tetramer, which is again stabilized by disulfide bridging between cysteine residues in the triple-helix regions.49,50,52 These tetramers are secreted into the extracellular space, where they associate in an end-to-end fashion to form characteristic ‘beads on a string’ collagen VI microfibrillar structures, which have a periodicity of 100–105 nm and a diameter of 4.5 nm (Figure 4).48,49,53,54

Physiological roles of collagen VI

In the extracellular matrix, collagen VI interacts with a large number of matrix molecules (Box 3). The identity of the molecular partner (or partners) mediating the interaction of collagen VI in the muscle basement membrane is not yet known. One possible candidate would be collagen type IV,40 the most important collagenous component of basement membranes. Since collagen VI binds to biglycan,55 which interacts with the sarcoglycan and dystroglycan complex,56,57 collagen VI might be indirectly linked to muscle cell surface receptors via biglycan and the dystrophin-associated protein complex.

Box 3. Molecules that interact with collagen VI.

In the extracellular matrix, collagen VI interacts with a large number of molecules and cell surface receptors: collagen II, collagen IV, fibulin 2, fibronectin, perlecan, microfibril-associated glycoprotein 1, membrane-associated chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4, heparin, hyaluran, decorin, biglycan, and collagen XIV.40,55,110–118

-

■

Biglycan and decorin interact with the N-terminus of collagen VI55

-

■

Biglycan seems to encourage branching of collagen VI into hexagonal networks119

-

■

Interactions of biglycan or decorin with matrilin 1 encourage the formation of large collagen VI complexes in the extracellular matrix120

-

■

Biglycan also interacts with the sarcoglycan and dystroglycan complex;56,57 thus, collagen VI might be indirectly linked to muscle cell surface receptors via biglycan and the dystrophin-associated protein complex

-

■

Cell binding to collagen VI might be mediated by the membrane-associated chondroitin proteoglycan NG2,116–118 and integrins α1β1 and α2β1, whereas integrins α5β1 and αVβ3 can bind to a hidden Arg–Gly–Asp motif in collagen VI58,121

Possible functions of collagen VI pertaining to various cell types have been suggested. These functions include the promotion of adhesion,58–60 proliferation,61 migration62,63 and survival.64,65 Collagen VI also has crucial roles in the regulation and differentiation of adipocytes and of normal and malignant mammary ductal cells.63,64,66 Judging by the clinical features seen in patients with collagen VI-related myopathies, the tissues where collagen VI has the most important roles include muscle, tendon and skin, although abnormalities in collagen VI might also have important, albeit more-subtle, effects in other tissues. In tendons, collagen VI is expressed by the resident tendon fibroblasts, around which it assumes a close pericellular distribution.41 In muscle, the cell of origin for collagen VI is the interstitial fibroblast.67,68 The collagen VI-related myopathies are quite unique, therefore, in that they are non-cell-autonomous disorders of muscle.

A mouse model of collagen VI deficiency has been generated by knockout of the collagen VI Col6a1 locus, resulting in a complete absence of collagen VI expression in muscle.69 In contrast to the human disease, these mice only show a mild neuromuscular disorder without much overt weakness.69 Muscles from these animals also show an increased incidence of apoptosis, which correlates with facilitated breakdown of the potential across the mitochondrial permeability pore when primed with oligomycin.65 This effect was preventable by inactivation of cyclophilin D using ciclosporin, its derivative Debio0025,70–72 or genetic inactivation of cyclophilin D.73 These interventions also resulted in decreased apoptosis and improved physiological functioning of isolated muscles from the collagen VI-knockout animals.65,72 Subsequent work using the same model suggests that impairments in autophagocytic flux (including impaired mitochondrial autophagy) also occur in the muscle cells of collagen VI-deficient mice, and possibly exacerbate the accumulation of defective mitochondria.74

Attachment of cells to the extracellular matrix is important for preventing apoptosis in general,75 which could be particularly relevant for muscle disorders that directly involve interactions between matrix and muscle, as is the case for both collagen VI-related and LAMA2-related CMDs.76–78 Work in cell cultures has shown that collagen VI-deficient cells exhibit decreased adherence to their surroundings,60,79 emphasizing the importance of this muscle cell–extracellular matrix interface.

Genotype–phenotype correlations

So far, all collagen VI mutations associated with the Ullrich CMD, intermediate or Bethlem myopathy spectra of disorders have occurred in the COL6A1, COL6A2 and COL6A3 genes,10 while no mutations have been observed to date in the newly recognized human collagen VI chains (COL6A5 and COL6A6).43,44

A genetic spectrum clearly underlies the clinical variability that is seen in the collagen VI-related myopathies. Although researchers initially thought that recessive mutations in the collagen VI genes underlie Ullrich CMD and that dominant mutations underlie Bethlem myopathy, this distinction is no longer valid. Ullrich CMD occurs through both recessive and dominant genetic mechanisms, the latter most typically as de novo autosomal-dominant mutations. In fact, in populations with a low degree of consanguinity, de novo autosomal-dominant mutations are the most common underlying mechanism of Ullrich CMD.1,30,32,80 Furthermore, although the typical genetic mechanism and pattern of inheritance for Bethlem myopathy is dominant, recessive mutations have also been seen in affected patients, albeit rarely.81,82 For example, the myosclerosis phenotype15 has emerged as a recessive form of Bethlem myopathy, in which a homozygous nonsense mutation in the COL6A2 gene results in a stable chain lacking the C2 domain but retaining the C1 domain,16 which presumably interferes with its ability to interact with other components in the extracellular matrix.

Recessive mutations that underlie typical Ullrich CMD mostly lead to complete absence of collagen VI in the extracellular matrix in muscle and in dermal fibroblast cultures.83 Such functional null alleles may be caused by nonsense mutations83 as well as splice-site mutations and intragenic deletions resulting in an out-of-frame transcript29,83,84 or in an assembly-incompetent chain (if located towards the C-terminal end of the collagenous triple-helical domain).80 If nonsense mutations affect alternatively spliced parts of the gene, such as the N-terminal globular domain of the collagen α3(VI) chain, their phenotypic effect can be milder than those of nonsense mutations in other sites.1,85–87

Although intragenic deletions in collagen VI loci have been recognized,88,89 large-scale genomic deletions can clearly also occur in the COL6A1 and COL6A2 locus on chromosome 21, encompassing the entirety of one or both of the collagen VI genes located there, or parts of one of the genes. Complete deletions of one copy of these genes also act in a recessive fashion, meaning that carriers of the deletion are clinically asymptomatic until a second mutation is present on the other allele. This characteristic also means that complete haploinsufficiency of all three collagen VI genes is not associated with clinical disease. Although homozygous missense mutations are a less common cause of severe Ullrich CMD than the null mutations discussed above, they have been described. Such mutations presumably affect crucial functions of the collagen VI protein and its interactions.16,90

Soon after the initial discovery of recessive mutations in collagen VI genes,83 a substantial number of patients with sporadic Ullrich CMD were found to carry de novo autosomal-dominant mutations in one of the three major collagen α(VI)-chain genes.30,32 Typically, this type of mutation leads to an in-frame skipping of exons in the N-terminal part of the α-chain domains. Owing to their location, such mutations do not prevent the C-terminal association of the three subunits of collagen VI, which allows the altered α-chain to be fully incorporated into the triple-helix monomer.80 If the cysteine residues in the N-terminal region of the triple helix (which are necessary for subsequent assembly of these monomers into tetramers) are spared by the deletion, only 1 in 16 of the resulting collagen VI tetramers will be completely normal, and the other 15 will include at least one mutant α-chain. This outcome is the basis of the strong dominant-negative effect of such mutations. Omissions of exon 16 in the α3(VI) chain account for the single most common mutation of this type, which is usually associated with a severe Ullrich CMD phenotype.32,80

Mutations that delete crucial cysteine residues in the collagenous triple helix domains of collagen VI subunits, as is the case for skipping of exon 14 in the α1(VI) chain, seem to have a more limited dominant-negative effect that shifts the clinical phenotype of collagen VI-related myopathy towards the mild end of the spectrum.30,80 Indeed, exon-14-skipping mutations are the single most common mutation type seen in patients with Bethlem myopathy.30,85,88,91–93 In-frame exon-skipping mutations located in the C-terminal end of the collagenous triple-helical domain interfere with assembly of the three peptide subunits into collagen VI monomers, with the consequence that abnormal peptides are prevented from assembly into tetramers. In patients who have collagen VI-related myopathies of intermediate severity, either dominant or recessive mechanisms might underlie their presentation, although a substantial number of patients will have exon-skipping mutations or de novo autosomal-dominant substitutions of glycine residues, as discussed below.

The other important dominant type of mutation is represented by substitutions of glycine residues in the Gly–X–Y motifs of the N-terminal collagenous triple-helical domain.14,85,93–95 This type of mutation is a common cause of collagen VI-related myopathy,96 and also acts in a dominant-negative fashion because mutated α-chain subunits can become incorporated into collagen VI monomers (although they introduce an ultrastructurally visible kink into the completed triple-helical domain).97 The molecular and clinical consequences of autosomal-dominant substitutions in Gly-X-Y motifs are variable and depend on the exact sequence context in which they occur.98 Glycine substitutions might, therefore, be seen in families affected by typical Bethlem myopathy, but also occur as de novo mutations in patients with sporadic collagen VI-related myopathy phenotypes in the Ullrich CMD or intermediate range.1,12,98

The pathogenetic effects and modes of action (recessive versus dominant) of other types of missense mutation are very difficult to predict.32,90 In addition, mutation analysis of the collagen VI genes has led to identification of a growing number of polymorphic variants of unknown significance. These variants require careful genetic and biochemical analysis to prove or disprove their pathogenetic roles. With the increased availability of mutational analysis, the fact that some patients with typical clinical features do not have a known mutation in one of the three collagen VI genes is becoming increasingly apparent.99 For patients with Bethlem myopathy and relatively mild phenotypes of intermediate collagen VI-related myopathy, the proportion of patients without mutations in the collagen VI genes has been reported as substantial—perhaps ≈25% (Bushby, personal communication).100 This figure may be considerably lower in patients who closely conform to the classic Ullrich CMD phenotype, but even among these individuals clear evidence exists for genetic heterogeneity.99

Treatment

Current approaches

The value and effect of appropriate general medical care in patients with collagen VI-related myopathies cannot be overestimated. Appropriate respiratory management alone has changed Ullrich CMD from a condition that was frequently lethal in teenage years into a condition in which survival well into adulthood should now be the norm.11 Even in the field of appropriate general medical management for patients with collagen VI-related myopathies, however, many challenges remain, including the optimal management of contractures and early scoliosis. Extensive prospective studies into the natural history of the collagen VI-related myopathies will be necessary to fully address these issues, and a review based on expert consensus on the standard of care of these conditions has been published.101

Future directions

Molecular therapies that would directly target the defects in collagen VI genes are conceivable but are in very early stages of development. To date, no single hypothesis can fully explain the development of muscle weakness in patients with the collagen VI-related myopathies or provide all targets for therapies, although important leads have been discovered. The most useful finding is that of increased myofiber apoptosis, which was reported in the mouse model of collagen VI deficiency.65 Pharmacological inhibition of cyclophilin D using ciclosporin or its derivative DEBIO-025 (alisporivir), which does not inhibit calcineurin, minimized this apoptosis in cultured human myoblasts from patients with collagen VI-related myopathy and in live collagen VI-deficient animals by interfering with the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores.70–72 In a small pilot study of five patients with collagen VI-related myopathies, biopsies were performed before and after 4 weeks of treatment with ciclosporin.102 This treatment apparently stabilized mitochondrial function, and fewer apoptotic nuclei were found in post-treatment biopsy samples than in pretreatment samples, suggesting an in vivo effect of ciclosporin in these patients.102 However, muscle strength was not measured in this study. Clearly these results will need to be validated in a controlled fashion in a large cohort of patients, preferably with an agent that has a more favorable long-term adverse-effect profile than that of ciclosporin. Potentially suitable drugs with a similar antiapoptotic mechanism to that of ciclosporin are on the horizon.

Additional data suggest that the increased opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores is not specific to the collagen VI-related disorders, but can also be seen in other neuromuscular disorders,103 which would mean that the treatment approach outlined above would be applicable in other muscle disorders, as has already been suggested for the δ-sarcoglycan-deficient and dystrophin-deficient mouse models.104 A crucial step will be to establish exactly how collagen VI deficiency in the extracellular matrix leaves muscle cells vulnerable to apoptosis; that is, how the presence of normal collagen VI in the extracellular matrix contributes to the health of myofibers. Elucidating the pathways involved will probably yield additional novel targets for therapeutic intervention.105 Furthermore, defective autophagy of malfunctioning cellular organelles might also underlie the increased apoptosis of muscle cells from animals and patients with collagen VI deficiency, and targeting of this pathway could result in additional treatments.74

Conclusions

The collagen VI-related myopathies are a unique group of muscle disorders that combine features of a muscle disease with those of a connective tissue disorder. The distinctive combinations of hyperlaxity, contractures and weakness associated with these disorders mean that they are usually readily recognizable from their clinical features. An increasingly established spectrum of disorders is now recognized, ranging from severe Ullrich CMD, via intermediate phenotypes, to the mild Bethlem myopathy. The genetic basis of these conditions is complex—both recessive and dominant mechanisms are possible for all clinical phenotypes of collagen VI-related myopathy, which can affect any of the three classic collagen VI genes, and evidence also exists for additional genetic heterogeneity in patients who are not carriers of collagen VI gene mutations. Careful evaluation of a given genetic variant is, therefore, necessary before it can be declared pathogenetic. Although much remains to be learned about the exact pathogenesis of these disorders, the finding of increased mitochondrially mediated apoptosis has revealed interesting treatment options that might soon lead to clinical trials.

Continuing Medical Education online.

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and Nature Publishing Group. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test and/or complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/nrneurol; (4) view/print certificate.

Released: 21 June 2011; Expires: 21 June 2012

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants should be able to:

Describe clinical features of Ullrich CMD and other collagen VI-related myopathies.

Describe mutations underlying collagen VI-related myopathies.

Describe treatment and management of collagen VI-related myopathies.

Key points.

-

■

The spectrum of collagen VI-related myopathies encompasses Ullrich muscular dystrophy and Bethlem myopathy as well as intermediate clinical phenotypes

-

■

Clinical hallmarks frequently include a combination of joint hyperlaxity and contractures in addition to weakness and nocturnal respiratory failure

-

■

Collagen VI-related myopathies are caused by mutations in the three major genes encoding the collagen VI α-chains—COL6A1, COL6A2 and COL6A3

-

■

Both dominant and recessive autosomal mutations underlie the entire phenotypic spectrum of these myopathies

-

■

The mutations result in formation of abnormal collagen VI and downstream effects that probably include increased apoptosis of muscle cells, which could represent a target for pharmacological treatments

Review criteria.

Papers were found by reviewing the existing literature and references therein. The main search terms used for a PubMed search included “collagen type VI”, “congenital muscular dystrophy”, “Ullrich”, “Bethlem”, “extracellular matrix” and “muscle”. Papers were selectively cited on the basis of their relevance to the context of this particular Review. Some identified papers were not included in the reference list owing to the restrictions on space and focus.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank members of his laboratory and participants of the 166th ENMC International Workshop on Collagen type VI-related Myopathies, for helpful discussions.

L. Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, is the author of and is solely responsible for the content of the learning objectives, questions and answers of the Medscape, LLC-accredited continuing medical education activity associated with this article.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The author, the journal Chief Editor H. Wood and the CME questions author L. Barclay declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Okada M, et al. Primary collagen VI deficiency is the second most common congenital muscular dystrophy in Japan. Neurology. 2007;69:1035–1042. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271387.10404.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norwood FL, et al. Prevalence of genetic muscle disease in northern England: in-depth analysis of a muscle clinic population. Brain. 2009;132:3175–3186. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peat RA, et al. Diagnosis and etiology of congenital muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2008;71:312–321. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000284605.27654.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ullrich O. Congenital, atonic–sclerotic muscular dystrophy, an additional type of heredo-degenerative illness of the neuromuscular system [German] Z. Ges. Neurol. Psychiat. 1930;126:171–201. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ullrich O. Congenital atonic–sclerotic muscular dystrophy [German] Monatsschr. Kinderheilkd. 1930;47:502–510. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furukawa T, Toyokura Y. Congenital, hypotonic–sclerotic muscular dystrophy. J. Med. Genet. 1977;14:426–429. doi: 10.1136/jmg.14.6.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nonaka I, et al. A clinical and histological study of Ullrich’s disease (congenital atonic-sclerotic muscular dystrophy) Neuropediatrics. 1981;12:197–208. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1059651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voit T. Congenital muscular dystrophies: 1997 update. Brain Dev. 1998;20:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(97)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertini E, Pepe G. Collagen type VI and related disorders: Bethlem myopathy and Ullrich scleroatonic muscular dystrophy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2002;6:193–198. doi: 10.1053/ejpn.2002.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lampe AK, Bushby KM. Collagen VI related muscle disorders. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:673–685. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2002.002311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadeau A, et al. Natural history of Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2009;73:25–31. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181aae851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinas L, et al. Early onset collagen VI myopathies: genetic and clinical correlations. Ann. Neurol. 2010;68:511–520. doi: 10.1002/ana.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jöbsis GJ, Boers JM, Barth PG, de Visser M. Bethlem myopathy: a slowly progressive congenital muscular dystrophy with contractures. Brain. 1999;122:649–655. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scacheri PC, et al. Novel mutations in collagen VI genes: expansion of the Bethlem myopathy phenotype. Neurology. 2002;58:593–602. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.4.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley WG, Hudgson P, Gardner-Medwin D, Walton JN. The syndrome of myosclerosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1973;36:651–660. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.36.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merlini L, et al. Autosomal recessive myosclerosis myopathy is a collagen VI disorder. Neurology. 2008;71:1245–1253. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327611.01687.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voermans NC, et al. Clinical and molecular overlap between myopathies and inherited connective tissue diseases. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2008;18:843–856. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexopoulos LG, Youn I, Bonaldo P, Guilak F. Developmental and osteoarthritic changes in Col6a1-knockout mice: biomechanics of type VI collagen in the cartilage pericellular matrix. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:771–779. doi: 10.1002/art.24293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirschner J, et al. Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy: connective tissue abnormalities in the skin support overlap with Ehlers–Danlos syndromes. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2005;132A:296–301. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voermans NC, Bönnemann CG, Lammens M, van Engelen BG, Hamel BC. Myopathy and polyneuropathy in an adolescent with the kyphoscoliotic type of Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2009;149A:2311–2316. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voermans NC, et al. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome due to tenascin-X deficiency: muscle weakness and contractures support overlap with collagen VI myopathies. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2007;143A:2215–2219. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minamitani T, et al. Modulation of collagen fibrillogenesis by tenascin-X and type VI collagen. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;298:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sipila L, et al. Secretion and assembly of type IV and VI collagens depend on glycosylation of hydroxylysines. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:33381–33388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quijano-Roy S, et al. De novo LMNA mutations cause a new form of congenital muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2008;64:177–186. doi: 10.1002/ana.21417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreiro A, et al. A recessive form of central core disease, transiently presenting as multi-minicore disease, is associated with a homozygous mutation in the ryanodine receptor type 1 gene. Ann. Neurol. 2002;51:750–759. doi: 10.1002/ana.10231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jungbluth H, et al. Autosomal recessive inheritance of RYR1 mutations in a congenital myopathy with cores. Neurology. 2002;59:284–287. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voermans NC, Bönnemann CG, Hamel BC, Jungbluth H, van Engelen BG. Joint hypermobility as a distinctive feature in the differential diagnosis of myopathies. J. Neurol. 2009;256:13–27. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schessl J, et al. Predominant fiber atrophy and fiber type disproportion in early ullrich disease. Muscle Nerve. 2008;38:1184–1191. doi: 10.1002/mus.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishikawa H, et al. Ullrich disease: collagen VI deficiency: EM suggests a new basis for muscular weakness. Neurology. 2002;59:920–923. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan TC, et al. New molecular mechanism for Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy: a heterozygous in-frame deletion in the COL6A1 gene causes a severe phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;73:355–369. doi: 10.1086/377107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishikawa H, et al. Ullrich disease due to deficiency of collagen VI in the sarcolemma. Neurology. 2004;62:620–623. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113023.84421.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker NL, et al. Dominant collagen VI mutations are a common cause of Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:279–293. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hicks D, et al. A refined diagnostic algorithm for Bethlem myopathy. Neurology. 2008;70:1192–1199. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000307749.66438.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jimenez-Mallebrera C, et al. A comparative analysis of collagen VI production in muscle, skin and fibroblasts from 14 Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy patients with dominant and recessive COL6A mutations. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2006;16:571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deconinck N, et al. Differentiating Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy and collagen VI-related myopathies using a specific CT scanner pattern. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2010;20:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mercuri E, et al. Muscle magnetic resonance imaging involvement in muscular dystrophies with rigidity of the spine. Ann. Neurol. 2010;67:201–208. doi: 10.1002/ana.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mercuri E, et al. Muscle MRI in Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and Bethlem myopathy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2005;15:303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bönnemann CG, Brockmann K, Hanefeld F. Muscle ultrasound in Bethlem myopathy. Neuropediatrics. 2003;34:335–336. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keene DR, Engvall E, Glanville RW. Ultrastructure of type VI collagen in human skin and cartilage suggests an anchoring function for this filamentous network. J. Cell Biol. 1988;107:1995–2006. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuo HJ, Maslen CL, Keene DR, Glanville RW. Type VI collagen anchors endothelial basement membranes by interacting with type IV collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26522–26529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ritty TM, Roth R, Heuser JE. Tendon cell array isolation reveals a previously unknown fibrillin-2-containing macromolecular assembly. Structure. 2003;11:1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Timpl R, Chu ML. In: Extracellular Matrix Assembly and Structure. Yurchenco PD, et al., editors. Orlando: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 207–242. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fitzgerald J, Rich C, Zhou FH, Hansen U. Three novel collagen VI chains, α4(VI), α5(VI), and α6(VI) J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:20170–20180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gara SK, et al. Three novel collagen VI chains with high homology to the α3 chain. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:10658–10670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sabatelli P, et al. Expression of the collagen VI α5 and α6 chains in normal human skin and in skin of patients with collagen VI-related myopathies. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011;131:99–107. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chu ML, et al. The structure of type VI collagen. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 1990;580:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb17917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aigner T, Hambach L, Söder S, Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, Pöschl E. The C5 domain of Col6A3 is cleaved off from the Col6 fibrils immediately after secretion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;290:743–748. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Engvall E, Hessle H, Klier G. Molecular assembly, secretion, and matrix deposition of type VI collagen. J. Cell Biol. 1986;102:703–710. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.3.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Furthmayr H, Wiedemann H, Timpl R, Odermatt E, Engel J. Electron-microscopical approach to a structural model of intima collagen. Biochem. J. 1983;211:303–311. doi: 10.1042/bj2110303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chu ML, et al. Amino acid sequence of the triple-helical domain of human collagen type VI. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:18601–18606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colombatti A, Mucignat MT, Bonaldo P. Secretion and matrix assembly of recombinant type VI collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:13105–13111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonaldo P, Russo V, Bucciotti F, Doliana R, Colombatti A. Structural and functional features of the α3 chain indicate a bridging role for chicken collagen VI in connective tissues. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1245–1254. doi: 10.1021/bi00457a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lamandé SR, et al. The role of the α3(VI) chain in collagen VI assembly. Expression of an α3(VI) chain lacking N-terminal modules N10-N7 restores collagen VI assembly, secretion, and matrix deposition in an α3(VI)-deficient cell line. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7423–7430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baldock C, Sherratt MJ, Shuttleworth CA, Kielty CM. The supramolecular organization of collagen VI microfibrils. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;330:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiberg C, et al. Biglycan and decorin bind close to the N-terminal region of the collagen VI triple helix. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:18947–18952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bowe MA, Mendis DB, Fallon JR. The small leucine-rich repeat proteoglycan biglycan binds to α-dystroglycan and is upregulated in dystrophic muscle. J. Cell Biol. 2000;148:801–810. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rafii MS, et al. Biglycan binds to α- and γ-sarcoglycan and regulates their expression during development. J. Cell Physiol. 2006;209:439–447. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aumailley M, Specks U, Timpl R. Cell adhesion to type VI collagen. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1991;19:843–847. doi: 10.1042/bst0190843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klein G, Müller CA, Tillet E, Chu ML, Timpl R. Collagen type VI in the human bone marrow microenvironment: a strong cytoadhesive component. Blood. 1995;86:1740–1748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawahara G, et al. Reduced cell anchorage may cause sarcolemma-specific collagen VI deficiency in Ullrich disease. Neurology. 2007;69:1043–1049. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271386.89878.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Atkinson JC, Rühl M, Becker J, Ackermann R, Schuppan D. Collagen VI regulates normal and transformed mesenchymal cell proliferation in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 1996;228:283–291. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perris R, Kuo HJ, Glanville RW, Bronner-Fraser M. Collagen type VI in neural crest development: distribution in situ and interaction with cells in vitro. Dev. Dyn. 1993;198:135–149. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001980207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iyengar P, et al. Adipocyte-derived collagen VI affects early mammary tumor progression in vivo, demonstrating a critical interaction in the tumor/stroma microenvironment. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1163–1176. doi: 10.1172/JCI23424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rühl M, et al. Soluble collagen VI drives serum-starved fibroblasts through S phase and prevents apoptosis via down-regulation of Bax. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:34361–34368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Irwin WA, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in myopathic mice with collagen VI deficiency. Nat. Genet. 2003;35:367–371. doi: 10.1038/ng1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakajima I, Muroya S, Tanabe R, Chikuni K. Extracellular matrix development during differentiation into adipocytes with a unique increase in type V and VI collagen. Biol. Cell. 2002;94:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(02)01189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zou Y, Zhang RZ, Sabatelli P, Chu ML, Bönnemann CG. Muscle interstitial fibroblasts are the main source of collagen VI synthesis in skeletal muscle: implications for congenital muscular dystrophy types Ullrich and Bethlem. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008;67:144–154. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e3181634ef7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Braghetta P, et al. An enhancer required for transcription of the Col6a1 gene in muscle connective tissue is induced by signals released from muscle cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2008;314:3508–3518. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bonaldo P, et al. Collagen VI deficiency induces early onset myopathy in the mouse: an animal model for Bethlem myopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:2135–2140. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.13.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Angelin A, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and prospective therapy with cyclosporins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:991–996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610270104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Angelin A, Bonaldo P, Bernardi P. Altered threshold of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1777:893–896. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tiepolo T, et al. The cyclophilin inhibitor Debio 025 normalizes mitochondrial function, muscle apoptosis and ultrastructural defects in Col6a1−/− myopathic mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;157:1045–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Palma E, et al. Genetic ablation of cyclophilin D rescues mitochondrial defects and prevents muscle apoptosis in collagen VI myopathic mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:2024–2031. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grumati P, et al. Autophagy is defective in collagen VI muscular dystrophies, and its reactivation rescues myofiber degeneration. Nat. Med. 2010;16:1313–1320. doi: 10.1038/nm.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chiarugi P, Giannoni E. Anoikis: a necessary death program for anchorage-dependent cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2008;76:1352–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Girgenrath M, Dominov JA, Kostek CA, Miller JB. Inhibition of apoptosis improves outcome in a model of congenital muscular dystrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:1635–1639. doi: 10.1172/JCI22928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miller JB, Girgenrath M. The role of apoptosis in neuromuscular diseases and prospects for anti-apoptosis therapy. Trends Mol. Med. 2006;12:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hayashi YK, et al. Massive muscle cell degeneration in the early stage of merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2001;11:350–359. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(00)00203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kawahara G, et al. Diminished binding of mutated collagen VI to the extracellular matrix surrounding myocytes. Muscle Nerve. 2008;38:1192–1195. doi: 10.1002/mus.21030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lampe AK, et al. Exon skipping mutations in collagen VI are common and are predictive for severity and inheritance. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:809–822. doi: 10.1002/humu.20704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Foley AR, et al. Autosomal recessive inheritance of classic Bethlem myopathy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2009;19:813–817. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gualandi F, et al. Autosomal recessive Bethlem myopathy. Neurology. 2009;73:1883–1891. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c3fd2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Camacho Vanegas O, et al. Ullrich scleroatonic muscular dystrophy is caused by recessive mutations in collagen type VI. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7516–7521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121027598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lucarini L, et al. A homozygous COL6A2 intron mutation causes in-frame triple-helical deletion and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in a patient with Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy. Hum. Genet. 2005;117:460–466. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lampe AK, et al. Automated genomic sequence analysis of the three collagen VI genes: applications to Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and Bethlem myopathy. J. Med. Genet. 2005;42:108–120. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.023754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Demir E, et al. Mutations in COL6A3 cause severe and mild phenotypes of Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1446–1458. doi: 10.1086/340608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Giusti B, et al. Dominant and recessive COL6A1 mutations in Ullrich scleroatonic muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2005;58:400–410. doi: 10.1002/ana.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pepe G, et al. COL6A1 genomic deletions in Bethlem myopathy and Ullrich muscular dystrophy. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:190–195. doi: 10.1002/ana.20705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bovolenta M, et al. Identification of a deep intronic mutation in the COL6A2 gene by a novel custom oligonucleotide CGH array designed to explore allelic and genetic heterogeneity in collagen VI-related myopathies. BMC Med. Genet. 2010;11:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang RZ, et al. Recessive COL6A2 C-globular missense mutations in Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy: role of the C2a splice variant. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:10005–10015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.093666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pepe G, et al. A heterozygous splice site mutation in COL6A1 leading to an in-frame deletion of the α1(VI) collagen chain in an italian family affected by Bethlem myopathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;258:802–807. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vanegas OC, et al. Novel COL6A1 splicing mutation in a family affected by mild Bethlem myopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:513–519. doi: 10.1002/mus.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lucioli S, et al. Detection of common and private mutations in the COL6A1 gene of patients with Bethlem myopathy. Neurology. 2005;64:1931–1937. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000163990.00057.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jöbsis GJ, et al. Type VI collagen mutations in Bethlem myopathy, an autosomal dominant myopathy with contractures. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:113–115. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pepe G, et al. A novel de novo mutation in the triple helix of the COL6A3 gene in a two-generation Italian family affected by Bethlem myopathy. A diagnostic approach in the mutations’ screening of type VI collagen. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1999;9:264–271. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(99)00014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Byers PH. Folding defects in fibrillar collagens. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2001;356:151–158. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lamandé SR, et al. Kinked collagen VI tetramers and reduced microfibril formation as a result of Bethlem myopathy and introduced triple helical glycine mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:1949–1956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109932200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pace RA, et al. Collagen VI glycine mutations: perturbed assembly and a spectrum of clinical severity. Ann. Neurol. 2008;64:294–303. doi: 10.1002/ana.21439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Petrini S, et al. Ullrich myopathy phenotype with secondary ColVI defect identified by confocal imaging and electron microscopy analysis. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2007;17:587–596. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Allamand V, Merlini L, Bushby K. 166th ENMC International Workshop on Collagen type VI-related Myopathies, 22–24 May 2009, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2010;20:346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang CH, et al. Consensus statement on standard of care for congenital muscular dystrophies. J. Child. Neurol. 2010;25:1559–1581. doi: 10.1177/0883073810381924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Merlini L, et al. Cyclosporin A corrects mitochondrial dysfunction and muscle apoptosis in patients with collagen VI myopathies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5225–5229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800962105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hicks D, et al. Cyclosporine A treatment for Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy: a cellular study of mitochondrial dysfunction and its rescue. Brain. 2009;132:147–155. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Millay DP, et al. Genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of mitochondrial-dependent necrosis attenuates muscular dystrophy. Nat. Med. 2008;14:442–447. doi: 10.1038/nm1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Collins J, Bönnemann CG. Congenital muscular dystrophies: toward molecular therapeutic interventions. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2010;10:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bethlem J, Wijngaarden GK. Benign myopathy, with autosomal dominant inheritance. A report on three pedigrees. Brain. 1976;99:91–100. doi: 10.1093/brain/99.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mohire MD, et al. Early-onset benign autosomal dominant limb-girdle myopathy with contractures (Bethlem myopathy) Neurology. 1988;38:573–580. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jöbsis GJ, et al. Genetic localization of Bethlem myopathy. Neurology. 1996;46:779–782. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pan TC, et al. Missense mutation in a von Willebrand factor type A domain of the α3(VI) collagen gene (COL6A3) in a family with Bethlem myopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:807–812. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.5.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bidanset DJ, et al. Binding of the proteoglycan decorin to collagen type VI. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:5250–5256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sasaki T, Gohring W, Pan TC, Chu ML, Timpl R. Binding of mouse and human fibulin-2 to extracellular matrix ligands. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;254:892–899. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tillet E, et al. Recombinant expression and structural and binding properties of α1(VI) and α2(VI) chains of human collagen type VI. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;221:177–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Finnis ML, Gibson MA. Microfibril-associated glycoprotein-1 (MAGP-1) binds to the pepsin-resistant domain of the α3(VI) chain of type VI collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:22817–22823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Specks U, et al. Structure of recombinant N-terminal globule of type VI collagen alpha 3 chain and its binding to heparin and hyaluronan. EMBO J. 1992;11:4281–4290. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Brown JC, Mann K, Wiedemann H, Timpl R. Structure and binding properties of collagen type XIV isolated from human placenta. J. Cell Biol. 1993;120:557–567. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.2.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Burg MA, Tillet E, Timpl R, Stallcup WB. Binding of the NG2 proteoglycan to type VI collagen and other extracellular matrix molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:26110–26116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.42.26110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Stallcup WB, Dahlin K, Healy P. Interaction of the NG2 chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan with type VI collagen. J. Cell Biol. 1990;111:3177–3188. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nishiyama A, Stallcup WB. Expression of NG2 proteoglycan causes retention of type VI collagen on the cell surface. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1993;4:1097–1108. doi: 10.1091/mbc.4.11.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wiberg C, Heinegard D, Wenglen C, Timpl R, Morgelin M. Biglycan organizes collagen VI into hexagonal-like networks resembling tissue structures. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:49120–49126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206891200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wiberg C, et al. Complexes of matrilin-1 and biglycan or decorin connect collagen VI microfibrils to both collagen II and aggrecan. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:37698–37704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pfaff M, et al. Integrin and Arg-Gly-Asp dependence of cell adhesion to the native and unfolded triple helix of collagen type VI. Exp. Cell Res. 1993;206:167–176. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]