Abstract

Vasopressin triggers the phosphorylation and apical plasma membrane accumulation of aquaporin 2 (AQP2), and it plays an essential role in urine concentration. Vasopressin, acting through protein kinase A, phosphorylates AQP2. However, the phosphorylation state of AQP2 could also be affected by the action of protein phosphatases (PPs). Rat inner medullas (IM) were incubated with calyculin (PP1 and PP2A inhibitor, 50 nM) or tacrolimus (PP2B inhibitor, 100 nM). Calyculin did not affect total AQP2 protein abundance (by Western blot) but did significantly increase the abundances of pS256-AQP2 and pS264-AQP2. It did not change pS261-AQP2 or pS269-AQP2. Calyculin significantly enhanced the membrane accumulation (by biotinylation) of total AQP2, pS256-AQP2, and pS264-AQP2. Likewise, immunohistochemistry showed an increase in the apical plasma membrane association of pS256-AQP2 and pS264-AQP2 in calyculin-treated rat IM. Tacrolimus also did not change total AQP2 abundance but significantly increased the abundances of pS261-AQP2 and pS264-AQP2. In contrast to calyculin, tacrolimus did not change the amount of total AQP2 in the plasma membrane (by biotinylation and immunohistochemistry). Tacrolimus did increase the expression of pS264-AQP2 in the apical plasma membrane (by immunohistochemistry). In conclusion, PP1/PP2A regulates the phosphorylation and apical plasma membrane accumulation of AQP2 differently than PP2B. Serine-264 of AQP2 is a phosphorylation site that is regulated by both PP1/PP2A and PP2B. This dual regulatory pathway may suggest a previously unappreciated role for multiple phosphatases in the regulation of urine concentration.

Keywords: aquaporin 2, phosphatase, membrane accumulation, calyculin, tacrolimus

vasopressin plays an essential role in the process of urine concentration. In response to vasopressin stimulation, aquaporin 2 (AQP2) phosphorylation is significantly enhanced (28, 29, 33). Phosphorylated AQP2 is transported from subapical intracellular storage vesicles to the apical plasma membrane, resulting in an increase in the water permeability of renal principal cells. AQP2 protein has four different phosphorylation sites: serine 256, serine 261, serine 264, and serine 269 (4, 5, 16, 20). Each of these phosphorylation sites plays an important role in regulating the subcellular vs. apical plasma membrane distribution of AQP2 (29).

The serine/threonine protein phosphatases (PP) can be divided into phosphoprotein phosphatases, metal-dependent protein phosphatases, and aspartate-based phosphatases (30). As for the subtypes of phosphoprotein phosphatases, the dephosphorylating actions of PP1, PP2A, and PP2B are Ca2+/calmodulin dependent. The PP family exerts an important role in tumorigenesis (18, 25), controlling neuronal function (19, 32), mediating insulin action (6, 22), and modulating cellular gene expression and viral transport (32). Calyculin is a potent inhibitor of PP1 and PP2A, and tacrolimus is a potent inhibitor of PP2B (15, 17, 26, 31). Both of them are valuable tools in studying the control of intracellular processes by reversible phosphorylation.

PP1 and PP2A regulate the phosphorylation, surface distribution, and function of the Na+/Cl−-dependent choline transporter (7). Potassium channels are also modulated by these phosphatases (36). Calyculin inhibits the activity of Na+-K+-ATPase at a lower dose than okadaic acid in renal proximal tubules (14). Calyculin affects actin phosphorylation in renal epithelial cells, which may be the cause of disorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (9). Moreover, PP2A and calcineurin increase the phosphorylation of the UT-A1 urea transporter in the absence of vasopressin (10). However, the role of phosphatases in the distribution and function of AQP2 has been sparsely reported. Jo et al. (11) showed that PP2B is expressed in the inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) and can mediate AQP2 dephosphorylation in rat IMCDs. Gooch et al. (8) showed that inhibition of PP2B causes alterations in AQP2 localization and phosphorylation in IMCDs from diabetic kidneys. Tamma et al. (34) showed that calyculin inhibition of PP2A causes increased p256-AQP2 and decreased p261-AQP2 in Madin Darby canine kidney (MDCK)-hAQP2 cells and that this facilitated AQP2 trafficking to the plasma membrane. The aim of the present study is to determine the effect of two different phosphatase inhibitors, calyculin and tacrolimus, on AQP2 phosphorylation and plasma membrane accumulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, body wt 200∼220 g) were maintained in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal care was supervised by the Emory University Division of Animal Research, and protocols were approved by the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Protein analysis.

Inner medullas (IM) were dissected from rat kidney and then cut into small pieces and incubated with calyculin (50 nM) or tacrolimus (100 nM) in a 37°C water bath. After 30 min, tissue was placed into ice-cold isolation buffer (10 mM triethanolamine, 250 mM sucrose, pH 7.6, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, and 2 mg/ml PMSF), homogenized, then SDS was added to a final concentration of 1% for Western analysis of the total cell lysate. Total protein in each sample was measured by a modified Lowry method (Bio-Rad DC protein assay reagent, Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Proteins were size-separated by SDS-PAGE on Laemmli gels and then electroblotted to PVDF membranes. PVDF membranes were blocked for 60 min with 5% nonfat dry milk before overnight incubation with primary antibodies: our total AQP2 (12, 24), pS256-AQP2 (Biorbyt, Burlington, NC; catalog no. orb317557), pS261-AQP2 (Avivasysbio, San Diego, CA; catalog no. OAPC00158), pS264-AQP2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Norcross, GA; catalog no. PA5-35387), pS269-AQP2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific; catalog no. PA5-35388), PP2A (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; catalog no. AF1653), and PP2B (R & D Systems; catalog no. AF1348). All primary antibodies were used at a concentration of 1:1,000, except total AQP2 was used at 1:4,000. Attached primary antibodies were identified using Alexa Fluor 680-linked anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; catalog no. A21076) and visualized using infrared detection with the LICOR Odyssey protein analysis system.

Biotinylation.

Calyculin (50 nM) or tacrolimus (100 nM) was added for 30 min at 37°C, and then IM samples were washed free of excess solution twice with PBS and three times with biotinylation buffer without biotin (in mM: 215 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 2 CaCl2, 5.5 glucose, 10 triethanolamine, 2.5 Na2HPO4). Calyculin or tacrolimus was added back to the incubation samples before incubation with 1 ml biotinylation buffer containing 3 mg/ml cell-impermeant biotinamidohexanoic acid 3-sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 60 min at 4°C. With this protocol, biotin does not enter the cells (9). Cells were then washed free of unattached biotin by three washes with biotin quenching buffer (in mM: 0.1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 260 glycine in PBS), with the last wash incubated for 20 min at 4°C. Next, samples were washed three times with lysis buffer without detergent and the cells were solubilized for 1 h in lysis buffer containing 1% NP-40 (in mM: 150 NaCl, 5 EDTA, 50 Tris). After centrifugation (14,000 g, 10 min, 4°C) to remove insoluble particulates, streptavidin beads were added to the supernatant fractions and allowed to absorb biotinylated proteins overnight at 4°C. After being washed with high-salt and no-salt buffers, Laemmli SDS-PAGE sample buffer was added directly to the pellets, samples were boiled for 1 min, and the pool of biotinylated proteins was analyzed by Western blot.

In vivo animal treatment.

To investigate the effect of acute calyculin or tacrolimus treatment on membrane localization, the rats were anesthetized by isoflurane. The abdominal skin was incised and the branching of the common iliac vessels was exposed. The needle was inserted into the iliac artery right before it branches. PBS (×1) was infused for 2–3 min, and then 5 ml of calyculin (500 nM) were injected into the same site. Immediately after the drug administration, the kidney artery and vein were clamped for 30 min. After the clamps were released, the kidney was perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde for 7 min. The kidney was harvested and prepared for immunostaining. Tacrolimus (1 mg/kg) was injected subcutaneously (10). After 45 min, the rat was anesthetized with isoflurane and the kidney was prepared for immunohistochemistry as described above.

Immunohistochemistry.

The animals were euthanized and their kidneys were perfusion fixed with paraformaldehyde. Paraffin sections of 5-μm thickness were sliced. Sections were dewaxed and hydrated in preparation for immunostaining as previously described (13). Sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: total AQP2, pS256-AQP2, pS261-AQP2, pS264-AQP2, and pS269-AQP2 or PP2A and PP2B. Slides were washed free of primary antibody and then incubated for 2 h in peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (donkey anti-rabbit IgG). Diaminobenzidine (DAB) and H2O2 were added to detect peroxidase activity and identify the primary antibodies as previously described (13). Slides were also stained with Mayer's hematoxylin to visualize nuclei. Stained sections were visualized using bright-field on an Olympus inverted microscope (IX71) at ×400 magnification.

Statistics.

Data were analyzed using a paired Student's t-test or repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by Fisher's least significant difference analysis for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

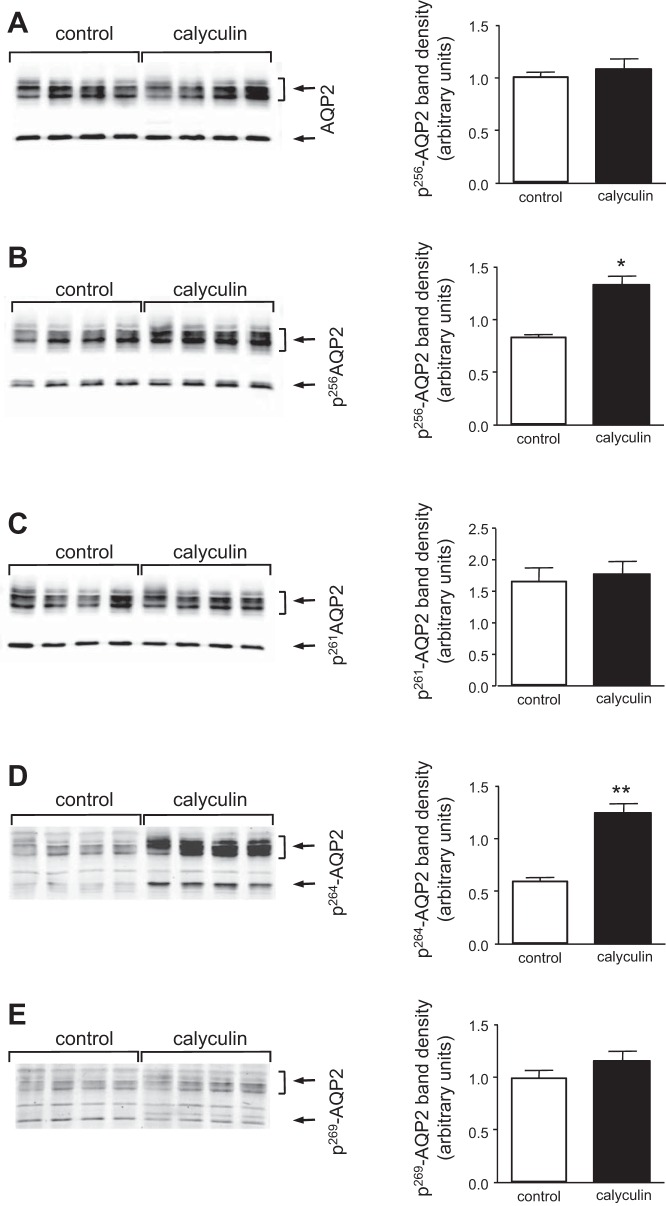

The administration of calyculin did not change total AQP2 expression, but enhanced the phosphorylation level at serine 256 and serine 264 of AQP2 in the IM.

The expression of AQP2 protein in rat IM was not changed by incubation with calyculin for 30 min (Fig. 1A). The abundance of pS256-AQP2 increased by 30% in calyculin-treated IM compared with control IM (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B). However, the amount of pS264-AQP2 increased strikingly to almost twice the level of the control group after 30 min of calyculin treatment (P < 0.01; Fig. 1C). In contrast, calyculin did not affect the phosphorylation level at Serine 261 or Serine 269 of AQP2 (Fig. 1, D and E, respectively). The ratios of pS256 and pS264-AQP2 to total AQP2 were markedly increased by 24 and 94%, respectively, while the ratios of pS261-AQP2 and pS269-AQP2 to total AQP2 were preserved compared with the control group (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Effect of calyculin on total aquaporin 2 (AQP2) and pSAQP2 abundance in rat kidney inner medulla. Rat inner medullas were harvested after 30-min incubation with or without calyculin (5 μM) and analyzed by Western blot for total AQP2 and pS-AQP2 (arrows) as follows: (A) total AQP2, (B) pS256-AQP2, (C) pS261-AQP2, (D) pS264-AQP2, and (E) pS269-AQP2. Left: representative Western blots. The combined densitometry of total AQP2 and pSAQP2 (n = 8, means ± SE) is shown in the right graphs, respectively. Open bars, control; filled bars, calyculin treated. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

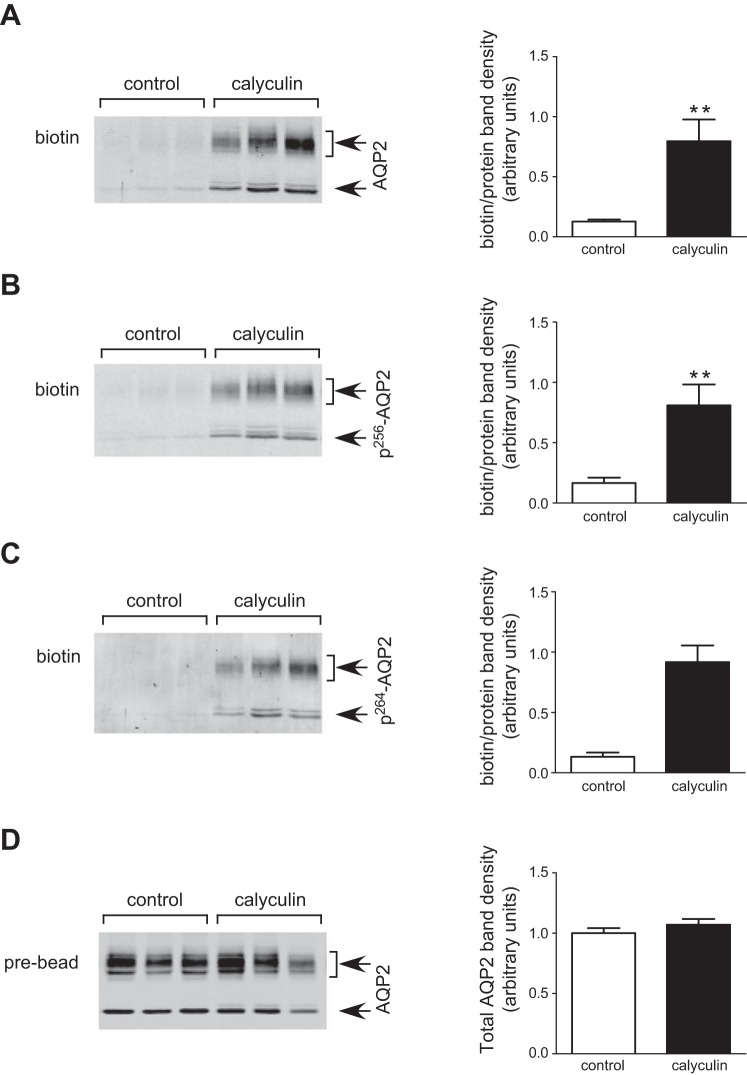

AQP2 accumulation in the cell membrane was increased by calyculin.

We performed surface biotinylation of rat IMCDs to detect the membrane density of total AQP2, pS256-AQP2, and pS264-AQP2. The results showed that the biotin/protein band density of total AQP2 was significantly increased by over six times in calyculin-treated IMCDs compared with the control group (P < 0.01), indicating that calyculin was able to promote the membrane accumulation of AQP2 in the IMCD (Fig. 2A). Moreover, calyculin significantly enhanced the abundance of pS256-AQP2 and pS264-AQP2 in the apical plasma membrane (Fig. 2, B and C).

Fig. 2.

AQP2 expression in the cell membrane in rat kidney inner medulla. Rat inner medullas were incubated in calyculin (5 μM) for 30 min immediately after being harvested, and an inner medullary collecting duct (IMCD) suspension was prepared. The suspended IMCDs were then biotinylated, and the biotinylated protein pool was analyzed by Western blot for biotin-AQP2 (arrows) as follows: (A) AQP2, (B) pS256-AQP2, (C) pS264-AQP2, and (D) pre-bead lysis sample. Left: representative Western blots. Combined densitometry of the biotinylated samples is shown in the right graphs (n = 8, means ± SE). Open bars, control; filled bars, calyculin treated. **P < 0.01.

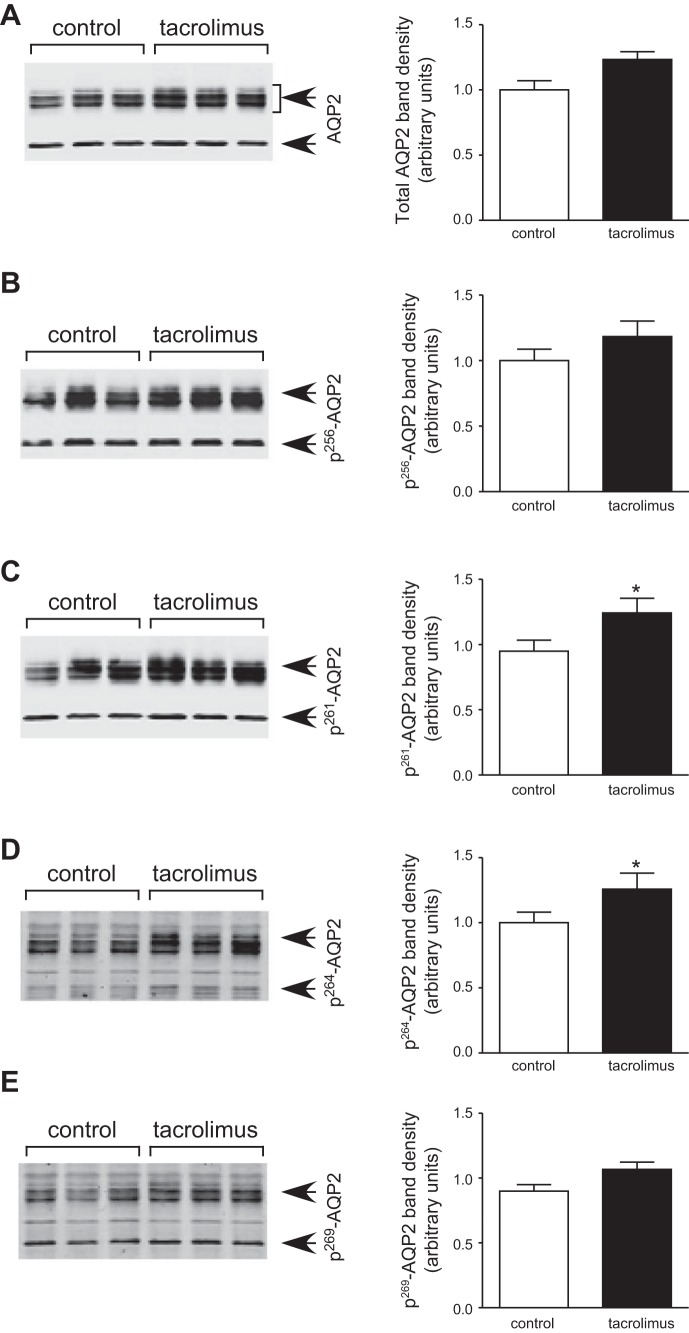

The administration of tacrolimus did not change AQP2 expression, but enhanced the phosphorylation level at serine 261 and serine 264 of AQP2 in the IM.

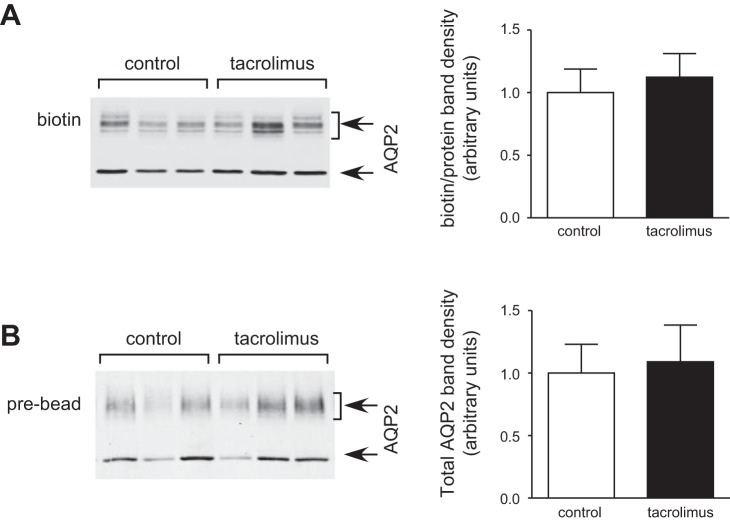

Western blot analysis showed that the tacrolimus treatment did not affect the abundance of AQP2 in the IM (Fig. 3A). After 30 min of tacrolimus treatment, the abundance of pS261-AQP2 increased significantly by 20% compared with the control group (Fig. 3C). Similarly, the amount of pS264-AQP2 increased significantly by 23% compared with the control rats (Fig. 3D). On the contrary, tacrolimus did not change the phosphorylation level at Serine 256-AQP2 (Fig. 3B) and Serine 269-AQP2 (Fig. 3E). Surface biotinylation analysis did not show significant membrane accumulation of total AQP2 in the IMCD (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Effect of tacrolimus on total AQP2 and pS-AQP2 abundance in rat kidney inner medulla. Rat inner medullas were harvested after 30-min incubation with or without tacrolimus (5 μM) and analyzed by Western blot for total AQP2 and pS-AQP2 (arrows) as follows: (A) total AQP2, (B) pS256-AQP2, (C) pS261-AQP2, (D) pS264-AQP2, and (E) pS269-AQP2. Left: representative Western blots. The combined densitometry of total AQP2 and pS-AQP2 (n = 8, means ± SE) is shown in the right graphs, respectively. Open bars, control; filled bars, calyculin treated. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

AQP2 expression in the cell membrane in rat kidney inner medulla. Rat inner medullas were incubated in tacrolimus (5 μM) for 30 min immediately after being harvested, and an IMCD suspension was prepared. The suspended IMCDs were then biotinylated, and the biotinylated protein pool was analyzed by Western blot for biotin-AQP2 (arrows) as follows: (A) AQP2 and (B) pre-bead lysis sample. Left: representative Western blots. Combined densitometry of the biotinylated samples is shown in the right graphs (n = 8, means ± SE). Open bars, control; filled bars, calyculin treated.

Short-term calyculin and tacrolimus treatment promoted the membrane accumulation of total AQP2, pS256-AQP2, and pS264-AQP2.

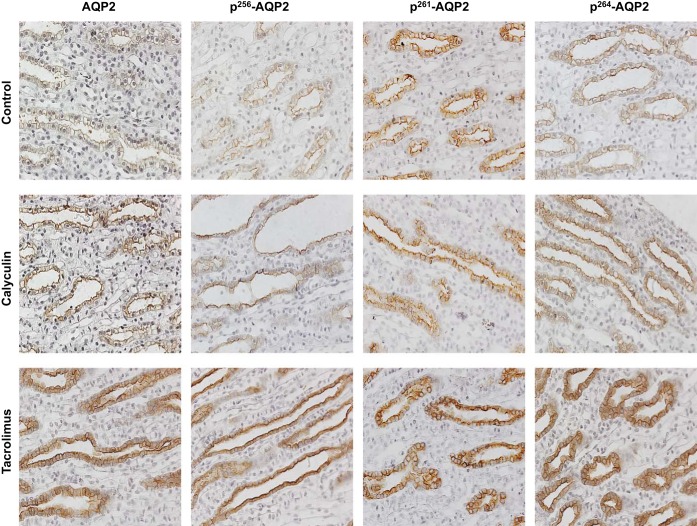

We infused the kidneys of control rats with calyculin and tacrolimus and then incubated the kidney IMCDs in situ for 30 and 45 min, respectively, as described in materials and methods. We then fixed the kidney with paraformaldehyde and prepared the tissue for immunostaining. The effects of the two PP inhibitors on the AQP2 membrane accumulation were determined by immunohistology. After short-term PP inhibitor treatment, the staining of total AQP2 in the apical plasma membrane appeared to be increased compared with the control rats (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Immunostaining for AQP2 and pSAQP2 in rat kidney inner medullas. Representative images (original magnification ×400) of immunostaining of rat inner medullary samples of control group (top), calyculin-treated group (middle), and tacrolimus-treated group (bottom) with AQP2, pS256-AQP2, pS261-AQP2, and pS264-AQP2. The apical membrane abundance of AQP2, pS256-AQP2, and pS264-AQP2 is increased in the calyculin- and tacrolimus-treated groups compared with the control group samples.

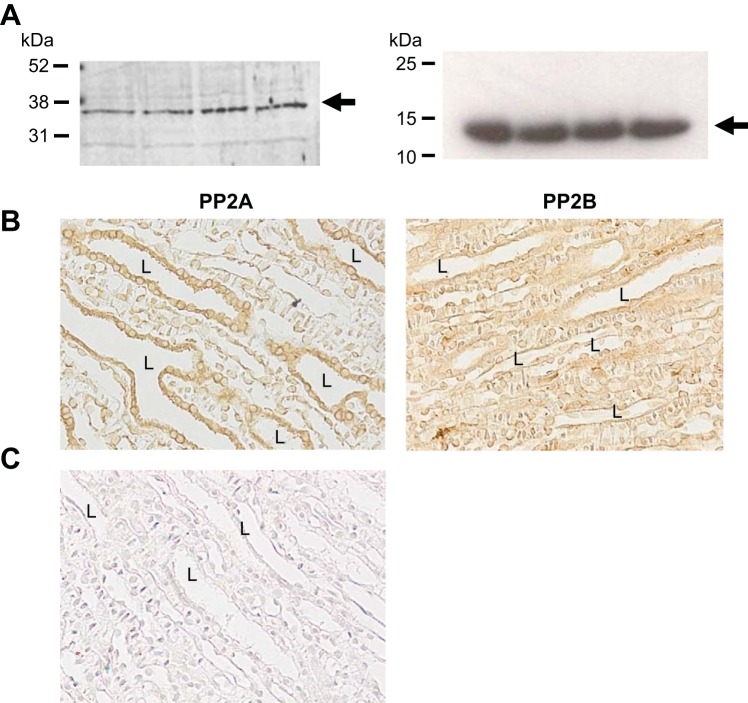

Localization of phosphatases in the IM.

We examined kidney IM tissue for the presence of PP2A, substrate for calyculin, and PP2B, substrate for tacrolimus, using Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry. PP2B and PP2A were identified in IM lysates (Fig. 6A). Immunohistology indicates both are widely distributed in a number of cell types but are clearly present in the IMCD cells (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Immunostaining for PP2A and PP2B in rat kidney inner medullas. A: rat inner medullas were harvested from untreated control rats and analyzed by Western blot for PP2A (36 kDa, left) and PP2B (calcineurin B, 19 kDa, right), with each protein being identified with an arrow. Shown are IM tissue samples from 4 individual rats. B: representative images (original magnification ×400) of immunostaining of rat inner medulla in paraffin sections from perfusion-fixed control rat kidney stained antibody to PP2A (left) and PP2B (right) and visualized with DAPA as described in materials and methods. Collecting duct lumens are identified by “L.” C: negative staining using secondary antibody only and developed with the slides that received both primary and secondary antibody.

DISCUSSION

The main result of the present study is that multiple phosphatases have different effects on AQP2 phosphorylation and plasma membrane accumulation. We took advantage of two different PP inhibitors to investigate the role of specific PPs in AQP2 regulation. Calyculin is a phosphatase 1and 2A inhibitor, which inhibits cell metabolism, signaling, and cell cycle progression (3, 23). Tacrolimus inhibits PP2B, which acts on calcium-dependent biological processes including immune responses, signal transduction, and muscle development (27). Both PP2A and PP2B (calcineurin) are present in the kidney inner medulla (Fig. 6A) and exhibit general cellular staining including the IMCD (Fig. 6B). PP inhibitors are used as immunosuppressive medications in transplant recipients and patients with autoimmune disorders (1, 2, 37). In our study, rat IMs were treated acutely with calyculin, tacrolimus, or vehicle ex vivo, and then IM tissue lysates were analyzed by Western blot. The results show that phosphorylation of different serine sites in AQP2 was modulated by calyculin and tacrolimus. Calyculin (PP1 and PP2A inhibitor) increased the phosphorylation of Ser256 and Ser264. On the other hand, tacrolimus (PP2B inhibitor) stimulated phosphorylation of Ser261 and Ser264. We also performed biotinylation of freshly isolated suspensions of IMCD tubules under the same treatment conditions to assess whether AQP2 membrane accumulation was affected by different phosphatases. Although plasma membrane accumulation of AQP2 was increased by calyculin, it was not changed by tacrolimus.

Different serine phosphorylation sites alter cellular AQP2 trafficking differently (29, 38). Ser256 phosphorylation is the critical site for vasopressin-induced AQP2 movement from intracellular vesicles to the apical plasma membrane in the IMCD (21). The Ser261 site has been linked to ubiquitination and intracellular vesicle association of AQP2 (35). Hence, the Ser261 site is thought to have an inhibitory effect on AQP2 membrane accumulation and water reabsorption. However, Lu et al. (16) showed that the phosphorylation state of Ser256 is dominant over that of Ser261. The abundance of p261-AQP2 in rat IM tissues did not vary with calyculin treatment in the current study, which is different from the results reported by Tamma et al. (34). This group saw a decrease in PP2A activity, which promoted the trafficking of p261-AQP2 in MDCK cells. This discrepancy may be due to different cell/tissue models (rat IM vs. MDCK cells) and variable treatment strategies (50 nM, 30 min in rat IM vs. 50 pM, 1 h in cultured MDCK cells). Fenton et al. (4) showed that the Ser264 phosphorylation site might be associated with driving AQP2 molecules to lysosomes. In a study by Fenton et al. (4), pSer264-AQP2 accumulation in the plasma membrane was increased within 15 min of vasopressin injection in a normal rat.

In our study, we showed that pSer256-AQP2 was increased by calyculin but not tacrolimus. Contrarily, pSer261-AQP2 abundance was increased by tacrolimus but not calyculin. PSer264-AQP2 was upregulated by both drugs compared with levels in control IMs. Moreover, calyculin increased the membrane accumulation of total AQP2 and pSer264-AQP2 in our biotinylation study while tacrolimus did not change the membrane accumulation of AQP2. Thus, we can suggest that PP1 and/or PP2A have a role in the internalization of membrane-associated AQP2 by downregulating Ser256 and Ser264 phosphorylations. However, PP2B does not change the membrane accumulation of AQP2. Immunohistochemical observation of these proteins verified that AQP2 was present at the membrane. We did not attempt to quantitate the amount of membrane-associated protein since biotinylation provides a more reliable estimation of this, but the location appears to be consistent with the biotinylation results. Because of these findings, we can suggest that PP1 and PP2A play a greater role in affecting AQP2 phosphorylation and regulating the urine concentration mechanism than PP2B. On the other hand, we previously showed that tacrolimus increases the membrane accumulation of UT-A1 (10). All in all, these results suggest that both PP1/PP2A and PP2B might represent novel targets to treat urine concentrating disorders.

Western blot analysis of biotinylated tubules showed pSer264-AQP2 was dramatically increased in the membrane by calyculin treatment. This finding agrees with a previous study showing that the Ser264 phosphorylation site is associated with membrane accumulation (4). Our immunohistochemistry results also confirmed the biotinylation findings. Calyculin cannot be administered systemically to a live animal. While direct treatment of the kidney with calyculin before immunohistochemical analysis seemingly confirmed the localization of the phosphorylated AQP2 forms, we cannot rule out the possible contribution of ischemia to the localization since the kidney was clamped for 30 min to allow exposure to calyculin. However, exposure to tacrolimus was systemic and would not have resulted in ischemic conditions. PSer264-AQP2 staining in the apical membrane of calyculin- or tacrolimus-treated rat IM was more intense than in control rats. Moreover, although tacrolimus increased Ser264 phosphorylation, it also increased Ser261 phosphorylation. However, membrane accumulation of AQP2 was not changed. This suggests that the Ser264 and Ser261 phosphorylations may have balancing effects on exocytosis and ubiqutination of intracellular AQP2 molecules.

In conclusion, PP1 and PP2A regulate the phosphorylation of AQP2 and its membrane accumulation in a different way from PP2B. Ser264 of AQP2 is a phosphorylation site that is regulated by both PP1/PP2A and PP2B. These findings may suggest a previously unappreciated role for multiple phosphatases in the regulation of urine concentration.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-DK89828 and R01-DK41707 and the research plan for CSC Scholarship Program and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81330074.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.R., J.M.S., and J.D.K. conception and design of research; H.R., J.A.R., O.E., and T.O.I. performed experiments; H.R., J.M.S., and J.D.K. analyzed data; H.R., J.M.S., and J.D.K. interpreted results of experiments; H.R., J.A.R., and J.D.K. prepared figures; H.R. and O.E. drafted manuscript; H.R., B.Y., J.M.S., and J.D.K. edited and revised manuscript; H.R., B.Y., J.A.R., J.M.S., and J.D.K. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asensio M, Chavez R, Ortega J, Iglesias J, Charco R, Margarit C. Experience with tacrolimus as primary immunosuppressor in pediatric liver transplant. Transplant Proc 34: 105–106, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caneguim BH, Cerri PS, Spolidorio LC, Miraglia SM, Sasso-Cerri E. Structural alterations in the seminiferous tubules of rats treated with immunosuppressor tacrolimus. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 7: 19, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fagerholm AE, Habrant D, Koskinen AM. Calyculins and related marine natural products as serine-threonine protein phosphatase PP1 and PP2A inhibitors and total syntheses of calyculin A, B, and C. Mar Drugs 8: 122–172, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenton RA, Moeller HB, Hoffert JD, Yu MJ, Nielsen S, Knepper MA. Acute regulation of aquaporin-2 phosphorylation at Ser-264 by vasopressin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3134–3139, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fushimi K, Sasaki S, Marumo F. Phosphorylation of serine 256 is required for cAMP-dependent regulatory exocytosis of the aquaporin-2 water channel. J Biol Chem 272: 14800–14804, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galbo T, Perry RJ, Nishimura E, Samuel VT, Quistorff B, Shulman GI. PP2A inhibition results in hepatic insulin resistance despite Akt2 activation. Aging 5: 770–781, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gates J Jr, Ferguson SM, Blakely RD, Apparsundaram S. Regulation of choline transporter surface expression and phosphorylation by protein kinase C and protein phosphatase 1/2A. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310: 536–545, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gooch JL, Pergola PE, Guler RL, Abboud HE, Barnes JL. Differential expression of Calcineurin A isoforms in the diabetic kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1421–1429, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu L, Zhang H, Chen Q, Chen J. Calyculin A-induced actin phosphorylation and depolymerization in renal epithelial cells. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 54: 286–295, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilori TO, Wang Y, Blount MA, Martin CF, Sands JM, Klein JD. Acute calcineurin inhibition with tacrolimus increases phosphorylated UT-A1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F998–F1004, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jo I, Ward DT, Baum MA, Scott JD, Coghlan VM, Hammond TG, Harris HW. AQP2 is a substrate for endogenous PP2B activity within an inner medullary AKAP-signaling complex. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F958–F965, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kishore BK, Krane CM, Di Iulio D, Menon AG, Cacini W. Expression of renal aquaporins 1, 2, and 3 in a rat model of cisplatin-induced polyuria. Kidney Int 58: 701–711, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein JD, Murrell BP, Tucker S, Kim YH, Sands JM. Urea transporter UT-A1 and aquaporin-2 proteins decrease in response to angiotensin II or norepinephrine-induced acute hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F952–F959, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D, Cheng SX, Fisone G, Caplan MJ, Ohtomo Y, Aperia A. Effects of okadaic acid, calyculin A, and PDBu on state of phosphorylation of rat renal Na+-K+-ATPase. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 275: F863–F869, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J, Farmer JD Jr, Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL. Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell 66: 807–815, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu HJ, Matsuzaki T, Bouley R, Hasler U, Qin QH, Brown D. The phosphorylation state of serine 256 is dominant over that of serine 261 in the regulation of AQP2 trafficking in renal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F290–F294, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Margassery LM, Kennedy J, O'Gara F, Dobson AD, Morrissey JP. A high-throughput screen to identify novel calcineurin inhibitors. J Microbiol Methods 88: 63–66, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCluskey A, Sim AT, Sakoff JA. Serine-threonine protein phosphatase inhibitors: development of potential therapeutic strategies. J Med Chem 45: 1151–1175, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merrill RA, Slupe AM, Strack S. N-terminal phosphorylation of protein phosphatase 2A/Bbeta2 regulates translocation to mitochondria, dynamin-related protein 1 dephosphorylation, and neuronal survival. FEBS J 280: 662–673, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moeller HB, Knepper MA, Fenton RA. Serine 269 phosphorylated aquaporin-2 is targeted to the apical membrane of collecting duct principal cells. Kidney Int 75: 295–303, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moeller HB, MacAulay N, Knepper MA, Fenton RA. Role of multiple phosphorylation sites in the COOH-terminal tail of aquaporin-2 for water transport: evidence against channel gating. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F649–F657, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Munro S, Cuthbertson DJ, Cunningham J, Sales M, Cohen PT. Human skeletal muscle expresses a glycogen-targeting subunit of PP1 that is identical to the insulin-sensitive glycogen-targeting subunit G(L) of liver. Diabetes 51: 591–598, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murata T, Shirakawa S, Takehara T, Kobayashi S, Haneji T. Protein phosphatase inhibitors, okadaic acid and calyculin A, induce alkaline phosphatase activity in osteoblastic cells derived from newborn mouse calvaria. Biochem Mol Biol Int 36: 365–372, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen S, DiGiovanni SR, Christensen EI, Knepper MA, Harris HW. Cellular and subcellular immunolocalization of vasopressin-regulated water channel in rat kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 11663–11667, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perrotti D, Neviani P. Protein phosphatase 2A: a target for anticancer therapy. Lancet Oncol 14: e229–238, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redden JM, Dodge-Kafka KL. AKAP phosphatase complexes in the heart. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 58: 354–362, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rusnak F, Mertz P. Calcineurin: form and function. Physiol Rev 80: 1483–1521, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sands JM. Understanding renal physiology leads to therapeutic advances in renal disease. Physiology 30: 171–172, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sands JM, Layton HE. Advances in understanding the urine-concentrating mechanism. Annu Rev Physiol 76: 387–409, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi Y. Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell 139: 468–484, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi Y, Reddy B, Manley JL. PP1/PP2A phosphatases are required for the second step of Pre-mRNA splicing and target specific snRNP proteins. Mol Cell 23: 819–829, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sontag E. Protein phosphatase 2A: the Trojan Horse of cellular signaling. Cell Signal 13: 7–16, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Takata K. Aquaporin-2 (AQP2): its intracellular compartment and trafficking. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 52: 34–39, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamma G, Lasorsa D, Trimpert C, Ranieri M, Di Mise A, Mola MG, Mastrofrancesco L, Devuyst O, Svelto M, Deen PM, Valenti G. A protein kinase A-independent pathway controlling aquaporin 2 trafficking as a possible cause for the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis associated with polycystic kidney disease 1 haploinsufficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 2241–2253, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamma G, Robben JH, Trimpert C, Boone M, Deen PM. Regulation of AQP2 localization by S256 and S261 phosphorylation and ubiquitination. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 300: C636–C646, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tiran Z, Peretz A, Sines T, Shinder V, Sap J, Attali B, Elson A. Tyrosine phosphatases epsilon and alpha perform specific and overlapping functions in regulation of voltage-gated potassium channels in Schwann cells. Mol Biol Cell 17: 4330–4342, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Truffa-Bachi P, Lefkovits II, Rudolf Frey J. Proteomic analysis of T cell activation in the presence of cyclosporin A: immunosuppressor and activator removal induces de novo protein synthesis. Mol Immunol 37: 261, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yumimoto K, Muneoka T, Tsuboi T, Nakayama KI. Substrate binding promotes formation of the Skp1-Cul1-Fbxl3 [SCF(Fbxl3)] protein complex. J Biol Chem 288: 32766–32776, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]