Abstract

Background

Evidence of the clinical safety of endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs) is limited and derived mainly from individual trials; therefore, we conducted a meta‐analysis.

Methods and Results

After systematic searches of the Medline, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases and the ClinicalTrials.gov website, randomized controlled trials with patients receiving ERAs (bosentan, macitentan, or ambrisentan) in at least 1 treatment group were included. All reported adverse events of ERAs were evaluated. Summary relative risks and 95% CIs were calculated using random‐ or fixed‐effects models according to between‐study heterogeneity. In total, 24 randomized trials including 4894 patients met the inclusion criteria. Meta‐analysis showed that the incidence of abnormal liver function (7.91% versus 2.84%; risk ratio [RR] 2.38, 95% CI 1.36–4.18), peripheral edema (14.36% versus 9.68%; RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.20–1.74), and anemia (6.23% versus 2.44%; RR 2.69, 95% CI 1.78–4.07) was significantly higher in the ERA group compared with placebo. In comparisons of individual ERAs with placebo, bosentan (RR 3.78, 95% CI 2.42–5.91) but not macitentan (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.42–3.31) significantly increased the risk of abnormal liver function, whereas ambrisentan (RR 0.06, 95% CI 0.01–0.45) significantly decreased that risk. Bosentan (RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.06–2.03) and ambrisentan (RR 2.02, 95% CI 1.40–2.91) but not macitentan (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.81–1.46) significantly increased the risk of peripheral edema. Bosentan (RR 3.09, 95% CI 1.52–6.30) and macitentan (RR 2.63, 95% CI 1.54–4.47) but not ambrisentan (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.20–8.48) significantly increased the risk of anemia. ERAs were not found to increase other reported adverse events compared with placebo.

Conclusions

The present meta‐analysis showed that the main adverse effects of treatment with ERAs were hepatic transaminitis (bosentan), peripheral edema (bosentan and ambrisentan), and anemia (bosentan and macitentan).

Keywords: adverse drug event, endothelin, endothelin receptor antagonists, meta‐analysis

Subject Categories: Pulmonary Hypertension

Introduction

Within 3 years of cloning of the 2 mammalian endothelin receptors, orally active endothelin receptor antagonists (ERAs) were tested in humans in the early 1990s, and the first clinical trial of ERA therapy for treating human disease was published in 1995. Four nonpeptide ERAs—bosentan, sitaxsentan, macitentan, and ambrisentan—that are either mixed endothelin ETA/ETB receptor antagonists or that display ETA selectivity have been developed for clinical use primarily in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), a progressive disease without a cure.1, 2, 3 To date, a number of published randomized double‐blind placebo‐controlled clinical trials have suggested that ERAs significantly improve exercise capacity, symptoms, cardiopulmonary hemodynamic variables, and slow clinical worsening.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Along with their widespread clinical use, the adverse effects of ERAs, such as elevation of liver transaminases, peripheral edema, anemia, and gastrointestinal reaction, were gradually reported.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Sitaxsentan, as the first selective ETA antagonist, has been authorized in the European Union since 2006 for the treatment of PAH and has been marketed in 16 European Union member states. Nevertheless, several reports of fatal liver injury with the use of sitaxsentan in PAH patients pushed Pfizer to withdraw the commercial drug from the market worldwide in 2010.9 Bosentan, ambrisentan, and macitentan are the current ERAs, thus it is necessary to assess their safety in clinical patients.

Studies designed to address the clinical safety of ERAs are currently lacking, and the limited evidence is related to reported adverse events in clinical trials of ERAs. Most of these trials included relatively small samples, and each study individually had only a small number of adverse events. To enhance precision by combining the results of individual studies and producing a single major effect, we conducted a systematic review and meta‐analysis of the adverse effects of ERAs.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

We conducted this review according to the methods recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration and documented the process and results in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses statement for reporting systematic reviews.10, 11 A systematic English‐language search of the Medline, Embase, and Cochrane Library electronic databases and the ClinicalTrials.gov website was conducted to identify all potential eligible trials (up to October 2015). Key terms used for the systematic search were “endothelin receptor antagonists or bosentan or ambrisentan or macitentan” and “clinical trial or controlled clinical trial or randomized controlled trial.” References of all pertinent articles were further scrutinized to ensure that all relevant studies were identified.

Study Selection

The following inclusion criteria for study selection were used: double‐blind randomized controlled trials; human participants; patients with any types of disease; studies consisting of at least 1 group receiving bosentan, ambrisentan, or macitentan therapy; studies including only adults (aged >18 years); and studies reporting relevant adverse events for ERAs and placebo groups separately. For multiple publications of 1 randomized controlled trial, we included the publication most relevant to our inclusion criteria in terms of detailed reporting of adverse events.

Data Extraction and Quality Evaluation

Two reviewers (A.W. and Z.G.) examined the electronic searches and obtained full reports of all citations that were likely to meet the selection criteria. Adverse events that were not reported in the publications were further extracted from the registry and results database (ClinicalTrials.gov). Disagreements were resolved by consensus after discussion. The data extracted from each study contained the name of the first author, study design, study duration, study population characteristics (age, sex, and number of patients), treatment groups, comparison groups, duration of follow‐up, and all reported adverse events. In addition, the GRADE approach was used to rate the quality of the included studies.12 To assess the methodological quality of randomized trials, we determined how the randomization sequence was generated, how allocation was concealed, whether there were important imbalances at baseline, which groups were blinded (patients, caregivers, data collectors, outcome assessors, data analysts), what the rate of loss to follow‐up was (in the intervention and control arms), whether the analyses were by intention to treat, and how studies dealt with missing outcome data. For each study, we also assessed how the population was selected, the duration and route of medication administration, the adequacy of study follow‐up, and the funding source.

Assessment of Bias

We used the criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews 5.1.0 to assess trial‐level risk of bias in the included studies.10 Two reviewers independently assessed studies for risk of bias. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus. A graph of the risk of bias and a summary were generated. Funnel plots were generated to assess for publication bias.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 5.3 software (Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration). Individual studies and meta‐analysis estimates were derived and presented in forest plots.13 Results are reported as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity, defined as variation beyond chance, was evaluated through the I2 test that measures the percentage of total variation between studies.14 For each meta‐analysis, the fixed‐effects analysis was performed; however, when I2 was >50%, high heterogeneity was assumed, and the random‐effects model was performed. P<0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

Subgroup analyses were performed by dosage of bosentan (125, 250, and 500 mg twice daily), ambrisentan (2.5, 5.0, and 10.0 mg once daily), and macitentan (3.0 and 10.0 mg once daily). Another subanalysis of ERAs versus placebo was performed according to disease type (PAH and other diseases). In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses using relative risk and different continuity correction factors to determine whether these choices of analysis methods affected the conclusions.

Results

Study Evaluation

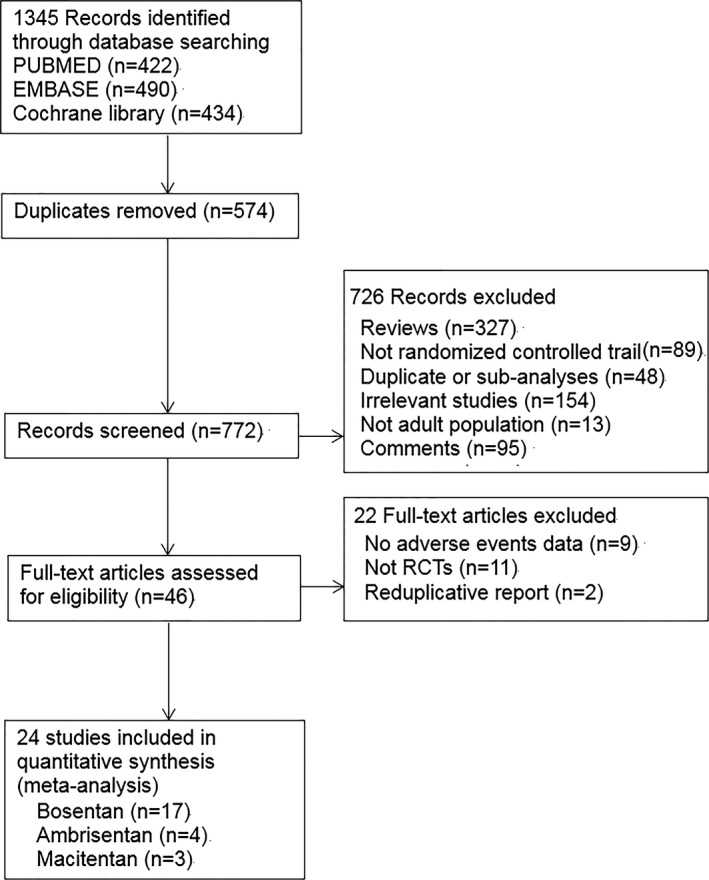

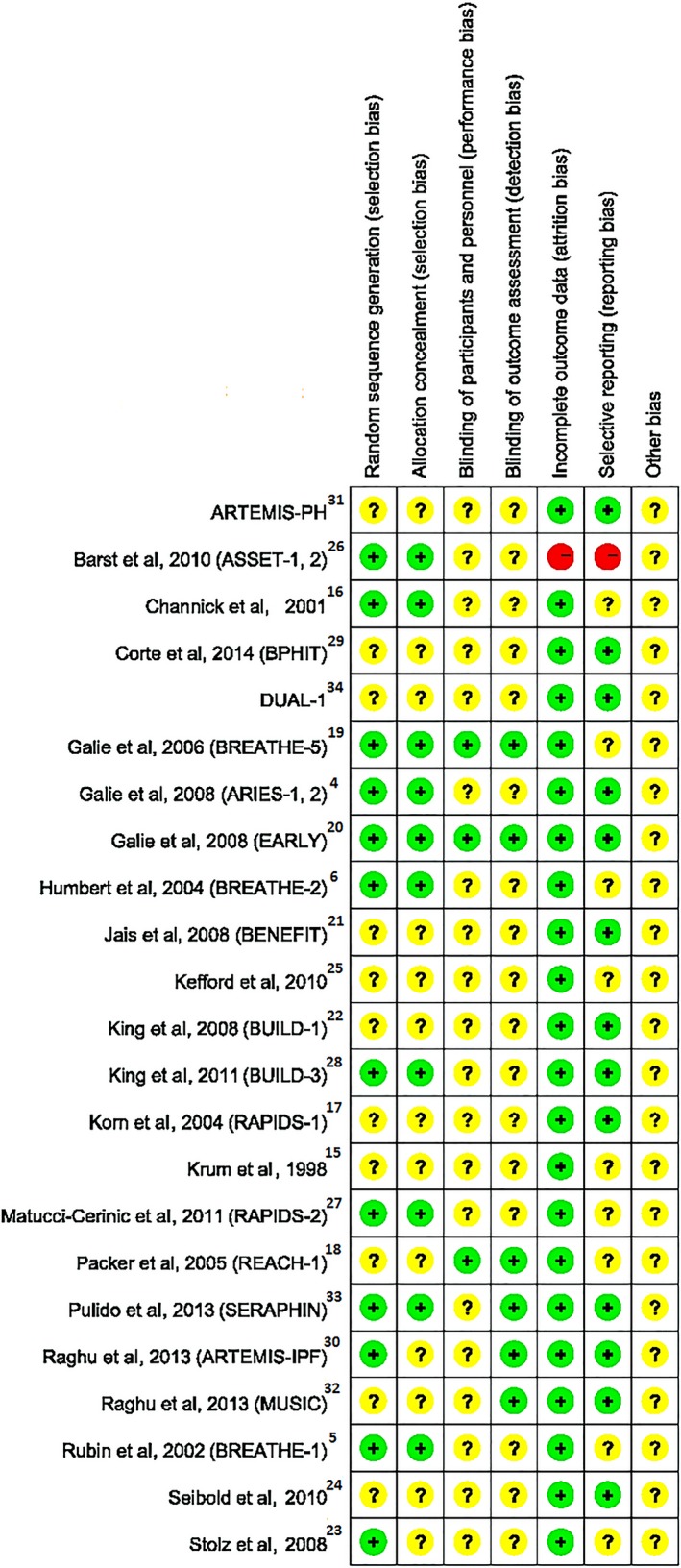

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the selection process to determine eligible studies. A total of 1345 studies were searched using the aforementioned retrieval methods, and 24 studies meeting the inclusion criteria were ultimately screened. In total, 4894 patients were included, consisting of 3084 patients in the medication group and 1810 patients in the placebo group. The characteristics of the 24 included studies are outlined in Table 1. All data included in the meta‐analysis were from randomized placebo‐controlled clinical trials, and the participants, clinicians, and assessors were blinded. All but 1 trial (ASSET‐1)26 had low risk of attrition bias. On this basis, we considered the quality of the evidence to be high. A summary of the risks of bias in the included studies is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the selection of eligible randomized controlled trials. RCT indicates randomized controlled trial.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Source | Design | Duration (Weeks) | Disease | Trial Group | Control Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | n | Treatment | n | ||||

| Krum et al, 199815 | RCT | 4 | Hypertension | Bosentan 100 mg/500 mg/1000 mg QD; 1000 mg BID | 194 | Placebo | 99 |

| Channick et al, 200116 | RCT | 12 | PAH | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 21 | Placebo | 11 |

| Rubin et al, 2002 (BREATHE‐1)5 | RCT | 16 | PAH | Bosentan 125 mg/250 mg BID | 144 | Placebo | 69 |

| Humbert et al, 2004 (BREATHE‐2)6 | RCT | 16 | PAH | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 22 | Placebo | 11 |

| Korn et al, 2004 (RAPIDS‐1)17 | RCT | 16 | SSc | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 79 | Placebo | 43 |

| Packer et al, 2005 (REACH‐1)18 | RCT | 26 | CHF | Bosentan 500 mg BID | 244 | Placebo | 126 |

| Galie et al, 2006 (BREATHE‐5)19 | RCT | 16 | PAH | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 37 | Placebo | 17 |

| Galie et al, 2008 (EARLY)20 | RCT | 24 | PAH | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 93 | Placebo | 92 |

| Jaïs et al 2008 (BENEFIT)21 | RCT | 16 | PAH | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 77 | Placebo | 80 |

| King et al, 2008 (BUILD‐1)22 | RCT | 48 | IPF | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 74 | Placebo | 84 |

| Stolz et al, 200823 | RCT | 12 | COPD | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 20 | Placebo | 10 |

| Seibold et al, 201024 | RCT | 48 | SSc | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 71 | Placebo | 81 |

| Kefford et al, 201025 | RCT | 96 | Metastatic melanoma | Bosentan 500 mg BID plus dacarbazine 1000 mg/m2 every 3 weeks | 38 | Placebo plus dacarbazine 1000 mg/m2 every 3 weeks | 38 |

| Barst et al, 2010 (ASSET‐1, 2)26 | RCT | 16 | PAH | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 11 | Placebo | 15 |

| Matucci‐Cerinic et al, 2011 (RAPIDS‐2)27 | RCT | 2 | SSc | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 96 | Placebo | 90 |

| King et al, 2011 (BUILD‐3)28 | RCT | 48 | IPF | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 406 | Placebo | 209 |

| Corte et al, 2014 (BPHIT)29 | RCT | 16 | PAH | Bosentan 125 mg BID | 40 | Placebo | 20 |

| Galie et al, 2008 (ARIES‐1)4 | RCT | 12 | PAH | Ambrisentan 5 mg/10 mg QD | 134 | Placebo | 67 |

| Galie et al, 2008 (ARIES‐2)4 | RCT | 12 | PAH | Ambrisentan 2.5 mg/5 mg QD | 127 | Placebo | 65 |

| Raghu et al, 2013 (ARTEMIS‐IPF)30 | RCT | 48 | IPF | Ambrisentan 10 mg QD | 329 | Placebo | 163 |

| ARTEMIS‐PH31 | RCT | 56 | PAH | Ambrisentan 10 mg QD | 15 | Placebo | 25 |

| Raghu et al, 2013 (MUSIC)32 | RCT | 52 | IPF | Macitentan 10 mg QD | 119 | Placebo | 59 |

| Pulido et al, 2013 (SERAPHIN)33 | RCT | 26 | PAH | Macitentan 3 mg/10 mg QD | 492 | Placebo | 249 |

| DUAL‐134 | RCT | 16 | SSc | Macitentan 3 mg/10 mg QD | 191 | Placebo | 97 |

CHF indicates chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SSc, systemic sclerosis.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias summary: review of authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study. + indicates low risk; −, high risk; ?, unclear risk.

Safety Analysis

All adverse events in the 24 trials were collected, and their absolute and relative frequencies in the treatment groups and the placebo groups were analyzed. The following adverse events were included for comparative analysis of tolerability and safety: blood and lymphatic system disorders (thrombocytopenia and anemia), cardiovascular disorders (cardiac failure, hypotension, and palpitation), gastrointestinal disorders (abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, and nausea), general disorders (peripheral edema, chest pain, fatigue, cough, and flushing), hepatobiliary disorders (abnormal liver function), infections (sinusitis, nasopharyngitis, respiratory tract infection, infected skin ulcer, pneumonia, and bronchitis), musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders (pain in extremity, back pain, leg pain, myalgia, and arthralgia), nervous system disorders (headache, dizziness, and syncope), and respiratory disorders (dyspnea, hypoxemia, and respiratory failure). RRs with their corresponding 95% CIs are presented in Table 2, and heterogeneity analysis was carried out for each of the 34 adverse events selected. The most significant results of the data from meta‐analyses are discussed next.

Table 2.

Relative Risk of Known Adverse Events Reported for ERAs in Comparison With Placebo

| ADR Outcomes | Studies | Participants | RR (95% CI) | Incidence Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood and lymphatic system disorder | ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 3 | 995 | 1.89 (0.74–4.83) | 1.85 |

| Anemia | 11 | 2859 | 2.69 (1.78–4.07) | 6.23 |

| Cardiovascular disorders | ||||

| Cardiac failure | 4 | 991 | 0.65 (0.48–0.88) | 12.36 |

| Hypotension | 6 | 2684 | 0.97 (0.69–1.38) | 4.44 |

| Palpitation | 8 | 1999 | 1.28 (0.77–2.14) | 3.38 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 7 | 1796 | 1.17 (0.55–2.52) | 1.35 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 4 | 1080 | 0.55 (0.26–1.20) | 1.81 |

| Diarrhea | 11 | 2711 | 0.90 (0.68–1.20) | 6.94 |

| Constipation | 7 | 1301 | 1.36 (0.88–2.11) | 6.82 |

| Vomiting | 6 | 1772 | 0.74 (0.48–1.13) | 3.28 |

| Nausea | 11 | 3204 | 0.81 (0.64–1.03) | 6.57 |

| General disorders | ||||

| Peripheral edema | 16 | 3853 | 1.44 (1.20–1.74) | 14.36 |

| Chest pain | 8 | 2909 | 0.96 (0.71–1.31) | 5.69 |

| Fatigue | 7 | 2476 | 0.98 (0.71–1.35) | 6.22 |

| Cough | 10 | 2916 | 0.73 (0.61–0.88) | 11.67 |

| Flushing | 8 | 1586 | 1.64 (0.97–2.79) | 5.03 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | ||||

| Abnormal liver function | 23 | 4854 | 2.38 (1.36–4.18) | 7.91 |

| Infections | ||||

| Sinusitis | 8 | 2754 | 1.17 (0.78–1.75) | 3.95 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 8 | 2560 | 1.15 (0.89–1.48) | 10.01 |

| Respiratory tract infection | 11 | 3125 | 1.0 (0.85–1.19) | 15.81 |

| Infected skin ulcer | 2 | 1029 | 0.82 (0.51–1.32) | 5.27 |

| Pneumonia | 6 | 2354 | 0.94 (0.60–1.48) | 3.20 |

| Bronchitis | 6 | 2354 | 0.98 (0.76–1.28) | 9.35 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | ||||

| Pain in extremity | 7 | 2001 | 0.77 (0.50–1.20) | 3.10 |

| Back pain | 6 | 2354 | 0.71 (0.52–0.98) | 5.38 |

| Leg pain | 2 | 155 | 0.87 (0.34–2.25) | 9.90 |

| Myalgia | 2 | 525 | 1.16 (0.18–7.47) | 0.85 |

| Arthralgia | 6 | 2130 | 0.99 (0.71–1.39) | 6.36 |

| Nervous system disorders | ||||

| Headache | 17 | 4382 | 1.09 (0.93–1.29) | 13.35 |

| Dizziness | 11 | 3312 | 1.03 (0.82–1.30) | 9.20 |

| Syncope | 6 | 2155 | 0.80 (0.52–1.23) | 3.49 |

| Respiratory disorders | ||||

| Dyspnea | 12 | 3061 | 1.17 (0.94–1.46) | 11.66 |

| Hypoxemia | 5 | 2066 | 1.01 (0.37–2.77) | 0.66 |

| Respiratory failure | 6 | 1667 | 1.84 (0.78–4.34) | 1.99 |

ADR indicates adverse drug reaction; ERA, endothelin receptor antagonists; RR, risk ratio.

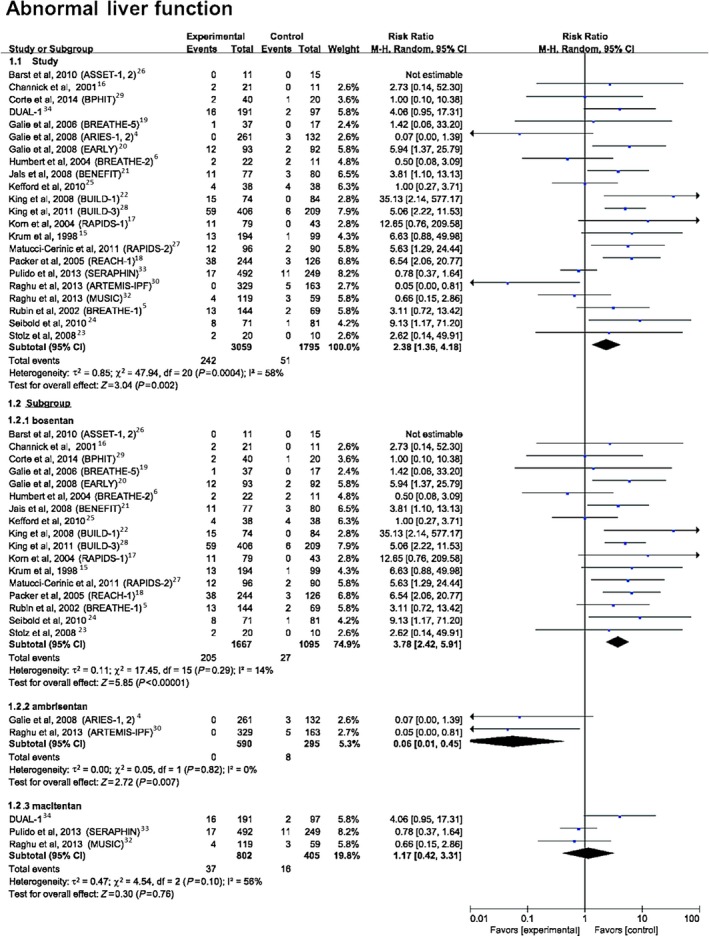

For abnormal liver function, defined as aspartate or alanine aminotransferase >3 times the upper limit of normal or treatment withdrawal due to elevated liver enzymes (Figure 3), the data showed a significantly higher risk with ERAs than placebo (7.91% versus 2.84%; RR 2.38, 95% CI 1.36–4.18, P=0.002). Further analyses comparing the 3 ERAs with placebo found that bosentan showed a significantly higher risk of abnormal liver function compared with placebo (12.30% versus 2.47%; RR 3.78, 95% CI 2.42–5.91, P<0.0001), whereas ambrisentan (0% versus 2.71%; RR 0.06, 95% CI 0.01–0.45, P=0.007) and macitentan (4.61% versus 3.95%; RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.42–3.31, P=0.76) did not show an increased risk compared with placebo.

Figure 3.

Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of abnormal liver function. Risk ratios and 95% CIs for the risk of abnormal liver function with endothelin receptor antagonist treatment. The size of data markers indicates the weight of each trial.

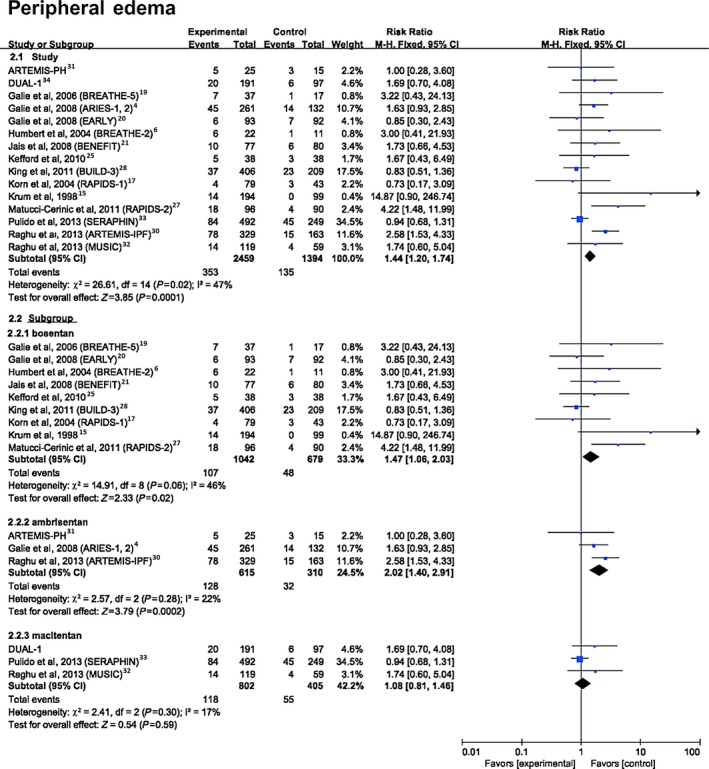

The data showed a significantly higher risk of peripheral edema with ERAs compared with placebo (14.36% versus 9.68%; RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.20–1.74, P=0.0001) (Figure 4). Further analyses comparing the 3 ERAs with placebo found that both bosentan (10.3% versus 7.1%; RR 1.47, 95% CI 1.06–2.03, P=0.02) and ambrisentan (20.8% versus 10.3%; RR 2.02, 95% CI 1.40–2.91, P=0.0002) showed a significantly higher risk of peripheral edema compared with placebo, whereas macitentan (14.7% versus 13.5%; RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.81–1.46, P=0.59) did not show an increased risk.

Figure 4.

Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of peripheral edema. Risk ratios and 95% CIs for the risk of peripheral edema with endothelin receptor antagonist treatment. The size of data markers indicates the weight of each trial.

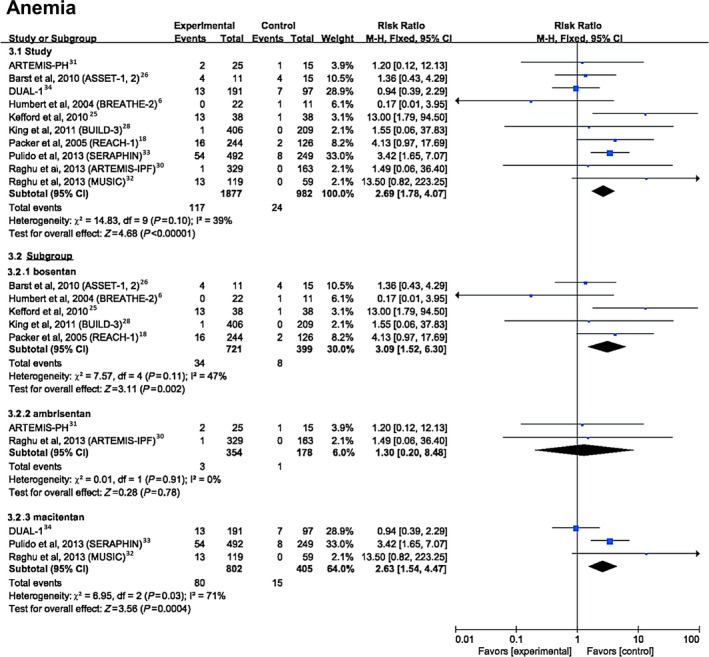

For anemia, defined as the absolute value of hemoglobin <120 g/L in women and <130 g/L in men35 (Figure 5), the data showed a significantly higher risk with ERAs compared with placebo (6.23% versus 2.44%; RR 2.69, 95% CI 1.78–4.07, P<0.0001). Further analyses showed that bosentan (4.72% versus 2.01%; RR 3.09, 95% CI 1.52–6.30, P=0.002) and macitentan (9.98% versus 3.7%; RR 2.63, 95% CI 1.54–4.47, P=0.0004) showed a significantly higher risk compared with placebo, whereas ambrisentan did not show an increased risk of anemia (0.85% versus 0.56%; RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.20–8.48, P=0.78).

Figure 5.

Forest plot with meta‐analysis for the risk of anemia. Risk ratios and 95% CIs for the risk of anemia with endothelin receptor antagonist treatment. The size of data markers indicates the weight of each trial.

As shown in Figure S1, the data showed a significantly lower risk of cough with ERAs compared with placebo (11.67% versus 16.42%; RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.61–0.88, P=0.0009). Bosentan (12.61% versus 17.50%; RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.59–0.97, P=0.03) and macitentan (10.31% versus 16.56%; RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.44–0.87, P=0.005) showed a significantly lower risk of cough compared with placebo, whereas no significantly different of cough incidence was observed between ambrisentan and placebo groups (11.58% versus 12.92%; RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.56–1.45, P=0.66).

The data did not show a significantly higher risk of dyspnea with ERAs compared with placebo (11.66% versus 10.35%; RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.94–1.46, P=0.15) (Figure S2); however, further analyses comparing the 3 ERAs with placebo found that ambrisentan (12.36% versus 7.10%; RR 1.77, 95% CI 1.13–2.76, P=0.01) showed significantly higher risk compared with placebo. An increased risk of dyspnea was not observed for other ERA treatment.

As shown in Table 2, no statistical difference was found in the incidence of other known adverse events (ie, thrombocytopenia, cardiac failure, hypotension, palpitation, abdominal pain, gastroesophageal reflux disease, diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, nausea, chest pain, fatigue, flushing, sinusitis, nasopharyngitis, respiratory tract infection, infected skin ulcer, pneumonia, bronchitis, pain in extremity, back pain, leg pain, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, dizziness, syncope, hypoxemia and respiratory failure) between ERA and placebo groups.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

A sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the weight of each study in each meta‐analysis. Sequentially dropping individual trials and then evaluating the overall outcomes failed to identify any individual trials as having influenced the results of the present meta‐analysis to a significant extent (Tables 3, 4, 5). The results of sensitivity analyses were consistent with and suggested the same global results as each meta‐analysis performed.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analysis With Meta‐Analysis of the Risk of Abnormal Liver Function

| Study Omitted | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Barst et al, 2010 (ASSET‐1, 2)26 | 2.38 | 1.36–4.17 |

| Channick et al, 200116 | 2.37 | 1.33–4.22 |

| Corte et al, 2014 (BPHIT)29 | 2.46 | 1.38–4.38 |

| Galie et al, 2006 (BREATHE‐5)19 | 2.41 | 1.35–4.28 |

| Galie et al, 2008 (EARLY)20 | 2.25 | 1.25–4.03 |

| Humbert et al, 2004 (BREATHE‐2)6 | 2.58 | 1.46–4.55 |

| Jaïs et al, 2008 (BENEFIT)21 | 2.30 | 1.26–4.17 |

| Kefford et al, 201025 | 2.52 | 1.40–4.53 |

| King et al, 2008 (BUILD‐1)22 | 2.21 | 1.27–3.84 |

| King et al, 2011 (BUILD‐3)28 | 2.23 | 1.23–4.04 |

| Korn et al, 2004 (RAPIDS‐1)17 | 2.27 | 1.28–4.00 |

| Krum et al, 199815 | 2.27 | 1.27–4.05 |

| Matucci‐Cerinic et al, 2011 (RAPIDS‐2)27 | 2.26 | 1.25–4.05 |

| Packer et al, 2005 (REACH‐1)18 | 2.21 | 1.23–3.96 |

| Rubin et al, 2002 (BREATHE‐1)5 | 2.34 | 1.29–4.23 |

| Seibold et al, 201024 | 2.24 | 1.26–3.98 |

| Stolz et al, 200823 | 2.37 | 1.33–4.22 |

| Galie et al, 2008 (ARIES‐1, 2)4 | 2.61 | 1.51–4.51 |

| Raghu et al, 2013 (ARTEMIS‐IPF)30 | 2.65 | 1.55–4.54 |

| DUAL‐134 | 2.30 | 1.27–4.15 |

| Pulido et al, 2013 (SERAPHIN)33 | 2.67 | 1.54–4.62 |

| Raghu et al, 2013 (MUSIC)32 | 2.58 | 1.45–4.57 |

RR indicates risk ratio.

Table 4.

Sensitivity Analysis With Meta‐Analysis of the Risk of Peripheral Edema

| Study Omitted | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Galie et al, 2006 (BREATHE‐5)19 | 1.42 | 1.18–1.72 |

| Galie et al, 2008 (EARLY)20 | 1.46 | 1.21–1.77 |

| Humbert et al, 2004 (BREATHE‐2)6 | 1.42 | 1.18–1.72 |

| Jaïs et al, 2008 (BENEFIT)21 | 1.43 | 1.18–1.73 |

| Kefford et al, 201025 | 1.43 | 1.19–1.73 |

| King et al, 2011 (BUILD‐3)28 | 1.57 | 1.28–1.92 |

| Korn et al, 2004 (RAPIDS‐1)17 | 1.45 | 1.20–1.75 |

| Krum et al, 199815 | 1.39 | 1.15–1.67 |

| Matucci‐Cerinic et al, 2011 (RAPIDS‐2)27 | 1.37 | 1.13–1.66 |

| ARTEMIS‐PH31 | 1.45 | 1.20–1.75 |

| Galie et al, 2008 (ARIES‐1, 2)4 | 1.41 | 1.16–1.72 |

| Raghu et al, 2013 (ARTEMIS‐IPF)30 | 1.29 | 1.05–1.58 |

| DUAL‐134 | 1.42 | 1.18–1.72 |

| Pulido et al, 2013 (SERAPHIN)33 | 1.70 | 1.35–2.13 |

| Raghu et al, 2013 (MUSIC)32 | 1.43 | 1.18–1.73 |

RR indicates risk ratio.

Table 5.

Sensitivity Analysis With Meta‐Analysis of the Risk of Anemia

| Study Omitted | RR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Barst et al, 2010 (ASSET‐1, 2)26 | 2.84 | 1.83–4.41 |

| Humbert et al, 2004 (BREATHE‐2)6 | 2.85 | 1.86–4.36 |

| Kefford et al, 201025 | 2.35 | 1.53–3.63 |

| King et al, 2011 (BUILD‐3)28 | 2.71 | 1.78–4.12 |

| Packer et al, 2005 (REACH‐1)18 | 2.55 | 1.66–3.94 |

| ARTEMIS‐PH31 | 2.74 | 1.80–4.19 |

| Raghu et al, 2013 (ARTEMIS‐IPF)30 | 2.71 | 1.78–4.12 |

| DUAL‐134 | 3.39 | 2.09–5.50 |

| Pulido et al, 2013 (SERAPHIN)33 | 2.32 | 1.40–3.85 |

| Raghu et al, 2013 (MUSIC)32 | 2.45 | 1.61–3.74 |

RR indicates risk ratio.

A subanalysis of drug dosage versus placebo was performed, and the results are shown in Table 6. Considering the risk of abnormal liver function, 3 subanalyses were carried out in the bosentan group (ie, for doses 125, 250, and 500 mg twice daily). All doses showed a significantly higher risk of abnormal liver function compared with placebo: The RRs were 4.71 (95% CI 3.04–7.32, P<0.00001) for 125 mg twice daily, 4.93 (95% CI 1.12–21.68, P=0.03) for 250 mg twice daily, and 3.76 (95% CI 1.64–8.12, P=0.002) for 500 mg twice daily. Interestingly, at dosages of 2.5 and 5.0 mg once daily, the ambrisentan group did not show a significant increase in risk of abnormal liver function compared with placebo. Nevertheless, the ambrisentan group at 10 mg once daily showed a significant decrease in the risk of abnormal liver function (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.01–0.87, P=0.04). Neither dosage of macitentan significantly increased the risk of abnormal liver function compared with placebo. Regarding peripheral edema, a significantly increased risk was found in the bosentan group (RR 1.46, 95% CI 1.05–2.04, P=0.03) at the dosage of 125 mg twice daily. The subanalysis of the bosentan group receiving 500 mg twice daily showed considerable heterogeneity (there was only 1 study), even when the random‐effects model was used (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.43–6.49, P=0.46). The ambrisentan group at 10 mg once daily showed a significantly higher risk of peripheral edema than placebo (RR 2.40, 95% CI 1.64–3.52, P<0.00001). The same risk was not found for ambrisentan at dosages of 2.5 and 5.0 mg once daily, with RRs of 0.29 (95% CI 0.07–1.26, P=0.10) and 1.74 (95% CI 0.94–3.21, P=0.08), respectively. No difference was found in the macitentan group with dosages of 3 and 10 mg once daily. A significantly increased risk of anemia was found in bosentan group at 500 mg twice daily (RR 6.57, 95% CI 2.11–20.43, P=0.001) but not at 125 mg twice daily (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.38–2.63, P=0.99). Because of considerable heterogeneity, the random‐effects model was used to evaluate the different doses of macitentan, with RRs of 1.51 (95% CI 0.42–5.44, P=0.53) for the group treated with 3 mg once daily and 2.87 (95% CI 0.88–9.32, P=0.08) for the group treated with 10 mg once daily.

Table 6.

Subgroup Analysis of ERAs Versus Placebo by Dosage

| Subgroups (Doses) | Studies | Participants | RR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal liver function | ||||

| Bosentan (total) | 17 | 2762 | 3.78 (2.42–5.91) | <0.00001 |

| Bosentan (125 mg BID) | 14 | 1953 | 4.71 (3.04–7.32) | <0.00001 |

| Bosentan (250 mg BID) | 1 | 139 | 4.93 (1.12–21.68) | 0.03 |

| Bosentan (500 mg BID) | 2 | 446 | 3.76 (1.64–8.62) | 0.002 |

| Ambrisentan (total) | 3 | 885 | 0.06 (0.01–0.45) | 0.007 |

| Ambrisentan (2.5 mg QD) | 1 | 196 | 0.29 (0.02–5.58) | 0.41 |

| Ambrisentan (5.0 mg QD) | 1 | 262 | 0.15 (0.01–2.78) | 0.20 |

| Ambrisentan (10.0 mg QD) | 2 | 691 | 0.11 (0.01–0.87) | 0.04 |

| Macitentan (total) | 3 | 1207 | 1.17 (0.42–3.31) | 0.76 |

| Macitentan (3.0 mg QD) | 2 | 690 | 1.08 (0.52–2.27) | 0.83 |

| Macitentan (10.0 mg QD) | 3 | 863 | 1.29 (0.69–2.40) | 0.42 |

| Peripheral edema | ||||

| Bosentan (total) | 9 | 1721 | 1.47 (1.06–2.03) | 0.02 |

| Bosentan (125 mg BID) | 8 | 1645 | 1.46 (1.05–2.04) | 0.03 |

| Bosentan (500 mg BID) | 1 | 76 | 1.67 (0.43–6.49) | 0.46 |

| Ambrisentan (total) | 4 | 925 | 2.02 (1.40–2.91) | 0.0002 |

| Ambrisentan (2.5 mg QD) | 1 | 196 | 0.29 (0.07–1.26) | 0.10 |

| Ambrisentan (5.0 mg QD) | 1 | 262 | 1.74 (0.94–3.21) | 0.08 |

| Ambrisentan (10.0 mg QD) | 3 | 731 | 2.40 (1.64–3.52) | <0.00001 |

| Macitentan (total) | 3 | 1207 | 1.08 (0.81–1.46) | 0.59 |

| Macitentan (3.0 mg QD) | 2 | 690 | 0.92 (0.64–1.33) | 0.66 |

| Macitentan (10.0 mg QD) | 3 | 863 | 1.20 (0.86–1.67) | 0.27 |

| Anemia | ||||

| Bosentan (total) | 5 | 1120 | 3.09 (1.52–6.30) | 0.002 |

| Bosentan (125 mg BID) | 3 | 674 | 0.99 (0.38–2.63) | 0.99 |

| Bosentan (500 mg BID) | 2 | 446 | 6.57 (2.11–20.43) | 0.001 |

| Macitentan (total) | 3 | 1207 | 2.63 (1.54–4.47) | 0.0004 |

| Macitentan (3.0 mg QD) | 2 | 690 | 1.51 (0.42–5.44) | 0.53 |

| Macitentan (10.0 mg QD) | 3 | 863 | 2.87 (0.88–9.32) | 0.08 |

ERA indicates endothelin receptor antagonist; RR, risk ratio.

A subanalysis of ERAs versus placebo according to disease type was also performed, and the results are shown in Table 7. Considering the common usage of ERAs, 2 subanalyses including PAH and other diseases were carried out in 3 ERA groups. Regardless of disease type, bosentan showed a significantly higher risk of abnormal liver function compared with placebo: The RRs were 2.85 (95% CI 1.52–5.33, P=0.001) in PAH and 5.70 (95% CI 3.54–9.18, P<0.00001) in other diseases. Ambrisentan did not significantly alter the risk of abnormal liver function in PAH (RR 0.07, 95% CI 0.00–1.39, P=0.08) but significantly decreased the risk of abnormal liver function in other diseases (RR 0.05, 95% CI 0.00–0.81, P=0.04). Macitentan did not alter the risk of abnormal liver function in either PAH (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.37–1.64, P=0.52) or other diseases (RR 1.64, 95% CI 0.27–10.16, P=0.59).

Table 7.

Subgroup Analysis of ERA Versus Placebo by Diagnosis

| Subgroups (Diagnosis) | Studies | Participants | RR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal liver function | ||||

| Bosentan (total) | 17 | 2762 | 3.78 (2.42–5.91) | <0.00001 |

| Bosentan (PAH) | 8 | 760 | 2.85 (1.52–5.33) | 0.001 |

| Bosentan (others) | 9 | 2002 | 5.70 (3.54–9.18) | <0.00001 |

| Ambrisentan (total) | 3 | 885 | 0.06 (0.01–0.45) | 0.007 |

| Ambrisentan (PAH) | 2 | 393 | 0.07 (0.00–1.39) | 0.08 |

| Ambrisentan (others) | 1 | 492 | 0.05 (0.00–0.81) | 0.04 |

| Macitentan (total) | 3 | 1207 | 1.17 (0.42–3.31) | 0.76 |

| Macitentan (PAH) | 1 | 741 | 0.78 (0.37–1.64) | 0.52 |

| Macitentan (others) | 2 | 466 | 1.64 (0.27–10.16) | 0.59 |

| Peripheral edema | ||||

| Bosentan (total) | 9 | 1721 | 1.47 (1.06–2.03) | 0.02 |

| Bosentan (PAH) | 4 | 429 | 1.57 (0.85–2.92) | 0.15 |

| Bosentan (others) | 5 | 1292 | 1.43 (0.98–2.09) | 0.06 |

| Ambrisentan (total) | 4 | 925 | 2.02 (1.40–2.91) | 0.0002 |

| Ambrisentan (PAH) | 3 | 433 | 1.52 (0.91–2.54) | 0.11 |

| Ambrisentan (others) | 1 | 492 | 2.58 (1.53–4.33) | 0.0004 |

| Macitentan (total) | 3 | 1207 | 1.08 (0.81–1.46) | 0.59 |

| Macitentan (PAH) | 1 | 741 | 0.94 (0.68–1.31) | 0.73 |

| Macitentan (others) | 2 | 466 | 1.71 (0.87–3.37) | 0.12 |

| Anemia | ||||

| Bosentan (total) | 5 | 1120 | 3.09 (1.52–6.30) | 0.002 |

| Bosentan (PAH) | 2 | 59 | 0.93 (0.34–2.54) | 0.88 |

| Bosentan (others) | 3 | 1061 | 5.80 (2.02–16.63) | 0.001 |

| Ambrisentan (total) | 2 | 532 | 1.30 (0.20–8.48) | 0.78 |

| Ambrisentan (PAH) | 1 | 40 | 1.20 (0.12–12.13) | 0.88 |

| Ambrisentan (others) | 1 | 492 | 1.49 (0.06–36.40) | 0.81 |

| Macitentan (total) | 3 | 1207 | 2.63 (1.54–4.47) | 0.0004 |

| Macitentan (PAH) | 1 | 741 | 3.42 (1.65–7.07) | 0.0009 |

| Macitentan (others) | 2 | 466 | 2.72 (0.15–48.16) | 0.50 |

Others include the diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, systemic sclerosis, or HFpEF. ERA indicates endothelin receptor antagonists; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; RR, risk ratio.

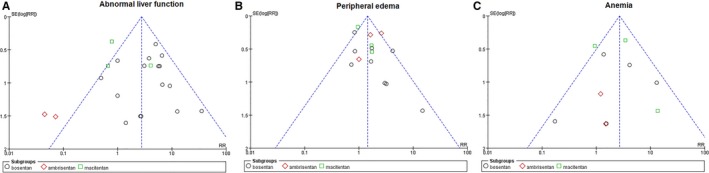

Publication Bias

Visual inspection of funnel plots for the analyses showed moderate symmetry, providing little evidence of publication bias (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Funnel plot to assess publication bias. Funnel plot of studies included in the meta‐analysis of the risk of (A) abnormal liver function, (B) peripheral edema, and (C) anemia. RR indicates risk ratio.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to pool current evidence for evaluation of all known adverse events of ERAs. Because sitaxsentan was withdrawn from global markets, bosentan, macitentan, and ambrisentan were included in our analysis, and their adverse event data were extracted from randomized controlled trials. Compared with placebo, the incidence of abnormal liver function, peripheral edema, and anemia were significantly higher in the ERA group. The incidence of cough was significantly lower compared with placebo (Figure S1). Although the incidence of some adverse events described in the package inserts of ERAs were high in the ERA group (ie, dyspnea, nasopharyngitis, respiratory tract infection and headache) (Table 2, Figures S2–S5), no difference was observed in the incidence of these adverse events between ERA and placebo groups.

Abnormal Liver Function

An important finding of the present meta‐analysis was that participants receiving ERAs had a higher adverse event rate of abnormal liver function than those given placebo. Further subanalyses of different ERAs found that bosentan significantly increased the risk of elevated liver transaminases, whereas ambrisentan significantly decreased the risk of abnormal liver function. No significant difference was noted in comparisons of macitentan and placebo.

The exact mechanism of ERA‐induced hepatotoxicity is not fully understood. Previous studies showed that it was likely to involve modulation of various hepatobiliary transporters, affinity for the ETB receptor, or specific hepatic metabolic and clearance pathways.36 In in vitro studies using sandwich‐cultured hepatocytes, bosentan has been shown to inhibit both basolateral sodium‐taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide and organic anion transporting polypeptides as well as the bile salt export pump and the multidrug resistance–associated protein 2, the net effect of which can lead to accumulation of cytotoxic bile acids.37, 38, 39 Furthermore, bosentan, as a dual ERA that competitively binds the ETA receptor with 20 times more affinity than the ETB receptor, is metabolized by cytochrome P450 isoenzymes CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 in the liver and is excreted almost entirely into the bile.40 The postmarketing surveillance database of 4623 patients receiving bosentan (TRAX‐PMS) showed that 7.6% of patients experienced elevated aminotransferases, which was concordant with the present meta‐analysis. The severity of liver enzyme elevation was most commonly between 3 and 5 times the upper limit of normal, and there were no cases of fatal liver injury related to bosentan use in TRAX‐PMS.41

In contrast, ambrisentan had weak inhibition of the bile salt export pump, which may partially explain the relatively low risk of hepatotoxicity.39 Ambrisentan, as a selective ERA that competitively binds the ETA receptor with 260 times more affinity than the ETB receptor, is metabolized by glucuronidation via the uridine 5′‐diphosphate glucuronosyltransferases and, to a lesser extent, by oxidation via CYP3A and CYP2C19 before excretion almost entirely into the bile.42 Our meta‐analysis showed that the incidence of abnormal liver function in patients receiving ambrisentan was lower than that for placebo. No abnormal liver function occurred in patients treated with ambrisentan in all inclusive study (ARIES‐1, ARIES‐2, and ARTEMIS‐IPF). Subanalyses of different dosages found that ambrisentan at the regular therapeutic dosage (10 mg once daily) had a lower risk of abnormal liver function than placebo. In ARIES‐1 and ARIES‐2, the incidence of abnormal liver function was 0% in the ambrisentan 10 mg group and 2.3% in the placebo group. In ARTEMIS‐IPF, the incidence of abnormal liver function was 0% in the ambrisentan 10 mg group and 3.1% in the placebo group. Interestingly, in an open‐label, phase II study of ambrisentan, 36 patients with PAH who had discontinued either bosentan or sitaxsentan due to liver transaminitis were given ambrisentan (Initial: 2.5 mg or 5 mg once daily; at 4‐week intervals, as tolerated and necessary, may increase the dose to 10 mg once daily), and no cases of elevated aminotransferase levels were ultimately reported at 12 weeks of follow‐up.43 Moreover, the results of post‐marketing surveillance report from Letairis Education and Access Program showed that only 0.72% of patients receiving ambrisentan developed a significant hepatic event.44 Based on data from the literature and findings from our meta‐analysis, we thought that ambrisentan had little hepatotoxicity and even showed a protective effect on liver function at the regular therapeutic dosage of 10 mg. Note that the US Food and Drug Administration removed the liver warning from ambrisentan in 2011, which is consistent with our finding.45

Interestingly, our data showed that despite their similar chemical structures and affinity for the ETB receptor,46 macitentan did not appear to have the same hepatotoxicity as bosentan. In vitro, macitentan is a more potent inhibitor of sodium‐taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide, organic anion transporting polypeptides, and the bile salt export pump than bosentan,39 thus further effort is necessary to explore the exact mechanism of ERA‐induced hepatotoxicity.

In summary, the current evidence demonstrated that macitentan and ambrisentan conferred a relatively low risk of hepatotoxicity compared with bosentan. Patients on bosentan should undergo more hepatic monitoring in the clinical setting.

Peripheral Edema

Peripheral edema, an important indicator of fluid retention in patients, is a known side effect of ERAs and a clinical consequence of PAH and its worsening.47 In the present study, there was a significantly higher risk of peripheral edema in the ERA group compared with the placebo group.

Further comparison of the 3 ERAs with placebo showed that bosentan and ambrisentan had significantly higher incidence of peripheral edema, but no significant difference was found in the macitentan group. Peripheral edema was a reported adverse effect of bosentan in 9 RCTs.6, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 25, 27, 28 In our further analysis, however, bosentan‐mediated peripheral edema did not appear to be a dose‐related effect. In the 3 trials conducted on ambrisentan, the incidence of peripheral edema was significantly higher in the treatment groups than in the placebo groups and was usually mild to moderate in severity. Further analysis showed that patients receiving ambrisentan at 10 mg once daily had a significantly higher risk of peripheral edema compared with those receiving placebo. The postmarketing reports in PAH patients showed that peripheral edema commonly occurred within weeks after starting ambrisentan. In addition, a previous study indicated that ambrisentan‐induced peripheral edema occurred with greater frequency and severity in elderly patients; 29% of patients aged >65 years developed peripheral edema in the treatment group compared with 4% in the placebo group.48 Consequently, as the most frequently reported adverse effect of ambrisentan, peripheral edema warrants attention at the clinic. Macitentan, unlike ambrisentan, showed a relatively low risk of peripheral edema.32, 33, 34 The SERAPHIN trial reported that the incidence of peripheral edema was 16% in the macitentan 3 mg group, 18.2% in the macitentan 10 mg group, and 18.1% in the placebo group.33

A previous study demonstrated that ERAs caused fluid retention by blocking natriuresis and diuresis mediated by the ETB receptors49 and possibly by the ETA receptors in the renal collecting ducts.50 Additional mechanisms, including unopposed precapillary arteriolar vasodilation and changes in capillary permeability, might account for the fluid retention induced by ERAs.48 In a recent post hoc subgroup analysis, a reduction of brain natriuretic peptide (P<0.001) occurred in patients on ambrisentan and with edema compared with the placebo group.48 This finding suggests that in the ambrisentan population, the mechanism for the presence of peripheral edema is unlikely to be cardiac dysfunction.

Anemia and Other Adverse Events

With respect to anemia, the present meta‐analysis showed a significant increase in the bosentan and macitentan groups, but the difference was not statistically significant between the ambrisentan and placebo groups. Although bosentan‐associated anemia was reported in 5 RCTs,6, 18, 25, 26, 28 it was generally mild, remained stable throughout treatment, and did not warrant treatment discontinuation. The ASSET‐1 trial reported that the decrease in hemoglobin was greater with bosentan than placebo.26 A >15% reduction in hemoglobin to an absolute value of <110 g/L occurred in 67% of treated patients but never necessitated discontinuation of bosentan.26 Consequently, it is currently recommended that hemoglobin levels be monitored every 3 months for the duration of bosentan therapy.51 Similarly, the data on macitentan derived from 3 trials showing higher incidence of anemia in the treatment group than the placebo group. In the SERAPHIN trial, the incidence of anemia in the 3 mg macitentan once daily, 10 mg macitentan once daily, and placebo groups was 8.8%, 13.2%, and 3.2%, respectively, which reflects a dose‐dependent effect of macitentan treatment.33 Interestingly, our study showed that ambrisentan was not associated with a relatively higher risk of reduction in hemoglobin concentration compared with placebo. Although in the ARIES‐1 and ARIES‐2 trials, hemoglobin concentrations decreased from baseline to week 12 by a mean of 0.84 g/dL (±1.2 g/dL) in patients treated with ambrisentan, the change in hemoglobin concentration was fairly stable during treatment.1 The mechanism by which anemia develops during ERAs therapy is unclear; however, it is thought to be partly secondary to increased fluid retention.52

Cough is a known adverse event described in the package insert of ERAs. Interestingly, although the reported incidence of cough was >10% in patients receiving bosentan (12.61%), macitentan (10.31%), and ambrisentan (11.58%), the overall pooled results showed a significantly lower risk of cough in ERAs compared with placebo. In addition, both bosentan and macitentan had a significantly lower risk of cough compared with placebo.

There were no significant differences between ERA and placebo groups for other known adverse events reported for ERAs.

Limitations

Several important limitations of our study should be taken into account to place its findings in the proper context. First, the observation time of the clinical trials included in our meta‐analysis was inconsistent, from 4 to 96 weeks, which might influence our results. Second, the evaluation criteria of different research centers for adverse events was variable. Third, publication and reporting biases may affect the results; therefore, further design of randomized controlled trials on evaluation of ERA safety and a long‐term observation study based on real‐world experience are necessary.

In conclusion, our meta‐analysis showed that hepatic transaminitis, peripheral edema, and anemia are the main adverse effects among those reported for ERAs. Ambrisentan was associated with higher risk of peripheral edema; macitentan conferred a higher risk of anemia; and bosentan increased a patient's risk of liver transaminitis, peripheral edema, and anemia. The latter results indicate that different monitoring parameters should be considered for different ERAs.

Author Contributions

Pu is the guarantor of the entire manuscript. Pu contributed to the study conception and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. Wei contributed to the study conception and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. Gu contributed to the study conception and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. Li contributed to the study conception and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. Liu contributed to the study conception and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. Wu contributed to the study conception and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published. Han contributed to the study conception and design; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; and final approval of the version to be published.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (to Pu), Program for New Century Excellent Talents of Ministry of Education of China NCET‐12‐0352 (NCET‐12‐0352), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (20152209), Shanghai Jiao Tong University (YG2013MS420) and Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (15ZH1003 and 14XJ10019).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of cough.

Figure S2. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of dyspnea.

Figure S3. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of nasopharyngitis.

Figure S4. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of respiratory tract infection.

Figure S5. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of headache.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003896 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003896)

Contributor Information

Yi Han, Email: hanyi79@163.com.

Jun Pu, Email: pujun310@hotmail.com.

References

- 1. Barnett CF, Alvarez P, Park MH. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: diagnosis and treatment. Cardiol Clin. 2016;34:375–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maarman G, Blackhurst D, Thienemann F, Blauwet L, Butrous G, Davies N, Sliwa K, Lecour S. Melatonin as a preventive and curative therapy against pulmonary hypertension. J Pineal Res. 2015;59:343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jin H, Wang Y, Zhou L, Liu L, Zhang P, Deng W, Yuan Y. Melatonin attenuates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension by inhibiting the inflammation and the proliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Pineal Res. 2014;57:442–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Galiè N, Olschewski H, Oudiz RJ, Torres F, Frost A, Ghofrani HA, Badesch DB, McGoon MD, McLaughlin VV, Roecker EB, Gerber MJ, Dufton C, Wiens BL, Rubin LJ. Ambrisentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the ambrisentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicenter, efficacy (ARIES) study 1 and 2. Circulation. 2008;117:3010–3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rubin LJ, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Galiè N, Black CM, Keogh A, Pulido T, Frost A, Roux S, Leconte I, Landzberg M, Simonneau G. Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Humbert M, Barst RJ, Robbins IM, Channick RN, Galiè N, Boonstra A, Rubin LJ, Horn EM, Manes A, Simonneau G. Combination of bosentan with epoprostenol in pulmonary arterial hypertension: BREATHE‐2. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barst RJ, Langleben D, Frost A, Horn EM, Oudiz R, Shapiro S, McLaughlin V, Hill N, Tapson VF, Robbins IM, Zwicke D, Duncan B, Dixon RA, Frumkin LR. Sitaxsentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barst RJ, Langleben D, Badesch D, Frost A, Lawrence EC, Shapiro S, Naeije R, Galie N. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension with the selective endothelin‐A receptor antagonist sitaxsentan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2049–2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Formulary Journal . Pfizer voluntarily withdraws sitaxsentan from the market worldwide and halts ongoing clinical trials. 2011. Available at: http://formularyjournal.modernmedicine.com/formulary-journal/news/clinical/clinical-pharmacology/pfizer-voluntarily-withdraws‐ sitaxsentan‐marke?page=full. Accessed August 24, 2014.

- 10. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Internet]. Available at: www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed 01.04.14. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–W94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swiglo BA, Murad MH, Schünemann HJ, Kunz R, Vigersky RA, Guyatt GH, Montori VM. A case for clarity, consistency, and helpfulness: state‐of‐the‐art clinical practice guidelines in endocrinology using the grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu R, Ding S, Zhao Y, Pu J, He B. Autologous transplantation of bone‐marrow/blood‐derived cells for chronic ischemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:1370–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lyu T, Zhao Y, Zhang T, Zhou W, Yang F, Ge H, Ding S, Pu J, He B. Natriuretic peptides as an adjunctive treatment for acute myocardial infarction: insights from the meta‐analysis of 1,389 patients from 20 trials. Int Heart J. 2014;55:8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krum H, Viskoper RJ, Lacourciere Y, Budde M, Charlon V. The effect of an endothelin‐receptor antagonist, bosentan, on blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. Bosentan Hypertension Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:784–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Channick RN, Simonneau G, Sitbon O, Robbins IM, Frost A, Tapson VF, Badesch DB, Roux S, Rainisio M, Bodin F, Rubin LJ. Effects of the dual endothelin‐receptor antagonist bosentan in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a randomised placebo‐controlled study. Lancet. 2001;358:1119–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, Rainisio M, Pope J, Hachulla E, Rich E, Carpentier P, Molitor J, Seibold JR, Hsu V, Guillevin L, Chatterjee S, Peter HH, Coppock J, Herrick A, Merkel PA, Simms R, Denton CP, Furst D, Nguyen N, Gaitonde M, Black C. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelin receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2004;50:3985–3993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Packer M, McMurray J, Massie BM, Caspi A, Charlon V, Cohen‐Solal A, Kiowski W, Kostuk W, Krum H, Levine B, Rizzon P, Soler J, Swedberg K, Anderson S, Demets DL. Clinical effects of endothelin receptor antagonism with bosentan in patients with severe chronic heart failure: results of a pilot study. J Card Fail. 2005;11:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Galiè N, Beghetti M, Gatzoulis MA, Granton J, Berger RM, Lauer A, Chiossi E, Landzberg M. Bosentan therapy in patients with Eisenmenger syndrome: a multicenter, double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled study. Circulation. 2006;114:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Galiè N, Rubin Lj, Hoeper M, Jansa P, Al‐Hiti H, Meyer G, Chiossi E, Kusic‐Pajic A, Simonneau G. Treatment of patients with mildly symptomatic pulmonary arterial hypertension with bosentan (EARLY study): a double‐blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:2093–2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jaïs X, D'Armini AM, Jansa P, Torbicki A, Delcroix M, Ghofrani HA, Hoeper MM, Lang IM, Mayer E, Pepke‐Zaba J, Perchenet L, Morganti A, Simonneau G, Rubin LJ. Bosentan for treatment of inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: BENEFiT (Bosentan Effects in iNopErable Forms of chronIc Thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension), a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2127–2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. King TE Jr, Behr J, Brown KK, du Bois RM, Lancaster L, de Andrade JA, Stähler G, Leconte I, Roux S, Raghu G. BUILD‐1: a randomized placebo‐controlled trial of bosentan in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stolz D, Rasch H, Linka A, Di Valentino M, Meyer A, Brutsche M, Tamm M. A randomised, controlled trial of bosentan in severe COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:619–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seibold JR, Denton CP, Furst DE, Guillevin L, Rubin LJ, Wells A, Matucci Cerinic M, Riemekasten G, Emery P, Chadha‐Boreham H, Charef P, Roux S, Black CM. Randomized, prospective, placebo‐controlled trial of bosentan in interstitial lung disease secondary to systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2010;62:2101–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kefford RF, Clingan PR, Brady B, Ballmer A, Morganti A, Hersey P. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of high‐dose bosentan in patients with stage IV metastatic melanoma receiving first‐line dacarbazine chemotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barst RJ, Mubarak KK, Machado RF, Ataga KI, Benza RL, Castro O, Naeije R, Sood N, Swerdlow PS, Hildesheim M, Gladwin MT. Exercise capacity and haemodynamics in patients with sickle cell disease with pulmonary hypertension treated with bosentan: results of the ASSET studies. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:426–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matucci‐Cerinic M, Denton CP, Furst DE, Mayes MD, Hsu VM, Carpentier P, Wigley FM, Black CM, Fessler BJ, Merkel PA, Pope JE, Sweiss NJ, Doyle MK, Hellmich B, Medsger TA Jr, Morganti A, Kramer F, Korn JH, Seibold JR. Bosentan treatment of digital ulcers related to systemic sclerosis: results from the RAPIDS‐2 randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. King TE Jr, Brown KK, Raghu G, du Bois RM, Lynch DA, Martinez F, Valeyre D, Leconte I, Morganti A, Roux S, Behr J. BUILD‐3: a randomized, controlled trial of bosentan in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Corte TJ, Keir GJ, Dimopoulos K, Howard L, Corris PA, Parfitt L, Foley C, Yanez‐Lopez M, Babalis D, Marino P, Maher TM, Renzoni EA, Spencer L, Elliot CA, Birring SS, O'Reilly K, Gatzoulis MA, Wells AU, Wort SJ. Bosentan in pulmonary hypertension associated with fibrotic idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raghu G, Behr J, Brown KK, Egan JJ, Kawut SM, Flaherty KR, Martinez FJ, Nathan SD, Wells AU, Collard HR, Costabel U, Richeldi L, de Andrade J, Khalil N, Morrison LD, Lederer DJ, Shao L, Li X, Pedersen PS, Montgomery AB, Chien JW, O'Riordan TG. Treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with ambrisentan: a parallel, randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. ARTEMIS‐PH—study of ambrisentan in subjects with pulmonary hypertension associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00879229. Accessed January 10, 2016.

- 32. Raghu G, Million‐Rousseau R, Morganti A, Perchenet L, Behr J. Macitentan for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the randomised controlled MUSIC trial. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1622–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pulido T, Adzerikho I, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Galiè N, Ghofrani HA, Jansa P, Jing ZC, Le Brun FO, Mehta S, Mittelholzer CM, Perchenet L, Sastry BK, Sitbon O, Souza R, Torbicki A, Zeng X, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G. Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Macitentan for the treatment of digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis patients. Available at: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT01474109. Accessed January 11, 2016.

- 35. McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993–2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:444–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aversa M, Porter S, Granton J. Comparative safety and tolerability of endothelin receptor antagonists in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Drug Saf. 2015;38:419–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fouassier L, Kinnman N, Lefèvre G, Lasnier E, Rey C, Poupon R, Elferink RP, Housset C. Contribution of mrp2 in alterations of canalicular bile formation by the endothelin antagonist bosentan. J Hepatol. 2002;37:184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fattinger K, Funk C, Pantze M, Weber C, Reichen J, Stieger B, Meier PJ. The endothelin antagonist bosentan inhibits the canalicular bile salt export pump: a potential mechanism for hepatic adverse reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lepist EI, Gillies H, Smith W, Hao J, Hubert C, St Claire RL, Brouwer KR, Ray AS. Evaluation of the endothelin receptor antagonists ambrisentan, bosentan, macitentan, and sitaxsentan as hepatobiliary transporter inhibitors and substrates in sandwich‐cultured human hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dingemanse J, van Giersbergen PL. Clinical pharmacology of bosentan, a dual endothelin receptor antagonist. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:1089–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Segal ES, Valette C, Oster L, Bouley L, Edfjall C, Herrmann P, Raineri M, Kempff M, Beacham S. Risk management strategies in the post‐marketing period: safety experience with the US and European bosentan surveillance programmes. Drug Saf. 2005;28:971–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Buckley MS, Wicks LM, Staib RL, Kirejczyk AK, Varker AS, Gibson JJ, Feldman JP. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of ambrisentan. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7:371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McGoon MD, Frost AE, Oudiz RJ, Badesch DB, Galie N, Olschewski H, McLaughlin VV, Gerber MJ, Dufton C, Despain DJ, Rubin LJ. Ambrisentan therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension who discontinued bosentan or sitaxsentan due to liver function test abnormalities. Chest. 2009;135:122–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ben‐Yehuda O, Pizzuti D, Brown A, Littman M, Gillies H, Henig N, Peschel T. Long‐term hepatic safety of ambrisentan in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:80–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. US Food and Drug Administration . FDA drug safety communication: liver injury warning to be removed from Letairis (ambrisentan) tablets. 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm245852.htm. Accessed August 24, 2014.

- 46. Sidharta PN, Krahenbuhl S, Dingemanse J. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of macitentan, a novel endothelin receptor antagonist for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:437–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Epstein BJ, Roberts ME. Managing peripheral edema in patients with arterial hypertension. Am J Ther. 2009;16:543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shapiro S, Pollock DM, Gillies H, Henig N, Allard M, Blair C, Anglen C, Kohan DE. Frequency of edema in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension receiving ambrisentan. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1373–1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gilead Sciences Inc . Letairis full prescribing information. 2014. Available at: http://www.gilead.com/~/media/Files/pdfs/medicines/cardiovascular/letairis/letairis_pi. Accessed August 24, 2014.

- 50. Ge Y, Bagnall A, Stricklett PK, Webb D, Kotelevtsev Y, Kohan DE. Combined knockout of collecting duct endothelin A and B receptors causes hypertension and sodium retention. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1635–F1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Humbert M, Segal ES, Kiely DG, Carlsen J, Schwierin B, Hoeper MM. Results of European post‐marketing surveillance of bosentan in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:338–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gabbay E, Fraser J, McNeil K. Review of bosentan in the management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2007;3:887–900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of cough.

Figure S2. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of dyspnea.

Figure S3. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of nasopharyngitis.

Figure S4. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of respiratory tract infection.

Figure S5. Forest plot with meta‐analysis of the risk of headache.