Abstract

Background

Systemic vasodilation using α‐receptor blockade has been shown to decrease the incidence of postoperative cardiac arrest following stage 1 palliation (S1P), primarily when utilizing the modified Blalock‐Taussig shunt. We studied the effects of a protocol in which milrinone was primarily used to lower systemic vascular resistance (SVR) following S1P using the right ventricular to pulmonary artery shunt, measuring its effects on oxygen delivery (DO 2) profiles and clinical outcomes. We also correlated Fick‐based assessments of DO 2 with commonly used surrogate measures.

Methods and Results

Neonates undergoing S1P were treated according to best clinical judgment prior to (n=32) and following (n=24) implementation of a protocol that guided operative, anesthetic, and postoperative management, particularly as it related to SVR. A majority of the subjects (n=51) received a modified right ventricular to pulmonary artery shunt. In a subset of these patients (n=21), oxygen consumption (VO 2) was measured and used to calculate SVR, DO 2, and oxygen debt. Neonates treated with the protocol had significantly lower SVR (P=0.02), serum lactate (P<0.001), and Sa‐vO 2 difference (P<0.001) and a lower incidence of CPR requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (E‐CPR, P=0.02) within the first 72 postoperative hours. DO 2 was closely associated with SVR (r2=0.78) but correlated poorly with arterial (SaO2) and venous (SvO2) oxyhemoglobin concentrations, the Sa‐vO 2 difference, and blood pressure.

Conclusions

A vasodilator protocol utilizing milrinone following S1P effectively decreased SVR, improved serum lactate, and decreased postoperative cardiac arrest. DO 2 correlated more closely with SVR than with Sa‐vO 2 difference, highlighting the importance of measuring VO 2 in this population.

Clinical Trial Registration

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT02184169.

Keywords: hypoplastic left heart syndrome, hypoxia, oxygen, oxygen consumption, phosphodiesterase inhibitor

Subject Categories: Congenital Heart Disease, Hemodynamics

Introduction

Since the initial description of the stage 1 palliation (S1P), the survival of neonates with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) has steadily improved.1, 2, 3 However, neonates with HLHS still suffer considerable morbidity in the early postoperative period, including sudden cardiac arrest, neurologic injury, and vital organ dysfunction. Several groups have described that the postoperative administration of phenoxybenzamine, a long‐acting α‐receptor antagonist, decreases the incidence of sudden cardiac arrest and narrows the arteriovenous oxyhemoglobin saturation difference (Sa‐vO2) following S1P.4, 5, 6 Decreasing systemic vascular resistance (SVR) is thought to increase systemic blood flow (SBF) relative to pulmonary blood flow (PBF) and also decreases ventricular afterload, increasing cardiac output.5, 6, 7 The majority of patients in contemporary studies have received a modified Blalock‐Taussig shunt (mBTS) as a source of PBF, in which case the impact of SVR on DO2 may be more pronounced due to diastolic flow patterns. At Boston Children's Hospital, we have recently altered the original Sano modification of the S1P utilizing a ring‐reinforced Goretex graft, which is “dunked” into the right ventricular cavity; this may decrease resistance to PBF in these patients, making the study of postoperative vasodilators important in this population.8, 9

Although the ultimate target of most interventions is to maximize DO2, this endpoint is challenging to measure in the single‐ventricle population. Measurement of DO2 is typically accomplished using the Fick principle: SaO2, systemic venous oxyhemoglobin saturation (SvO2, typically measured from the superior vena cava), hemoglobin, oxygen consumption (VO2), and pulmonary venous oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpvO2) are either measured directly or assumed. In early experience it was proposed that SaO2 in isolation could be used to assess the pulmonary‐to‐systemic blood flow ratio (Qp/Qs) and DO2 10; however, because SaO2 is itself determined by SvO2, SpvO2, and Qp/Qs in single ventricle physiology, it is not useful as an indicator of DO2 in isolation.11 Contemporary groups have since shown that SvO2 and Sa‐vO2 difference are more closely related to DO2.5, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 This makes physiologic sense, as a diminution in DO2 typically leads to tissue hypoxia, resulting in increased oxygen extraction and desaturation of the venous blood. Although SaO2 and SvO2 are independently meaningful parameters, they are typically combined with estimated (rather than measured) VO2 in order to calculate systemic blood flow (SBF) and DO2. However, it has been increasingly appreciated that VO2 is highly variable in the single‐ventricle population (potentially more so than SaO2 or SvO2) and that the accurate determination of DO2 requires the direct and continuous measurement of VO2.16, 17 Real‐time quantification of VO2 has been extensively described in the literature using a modified mass spectrometer fitted with a Douglas bag (AMIS 2000, Innovision A/S, Innocor, Inc, Odense, Denmark).16 However, the device has not been introduced in the United States, is cumbersome to use, and is no longer being manufactured (personal communjcation, Innocor, Inc). In hopes of making real‐time measurement of VO2 (and calculation of DO2) feasible for a broad range of users, we utilized a commercially available breath‐to‐breath system that utilizes a paramagnetic oxygen sensor combined with spirometry (E‐COVX gas module, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) to quantify VO2 in a subset of these patients.

Thus, we evaluated the impact of a vasodilatory protocol utilizing milrinone (an inodilator) on perioperative DO2, the incidence of postoperative cardiac arrest, and other clinically important endpoints. We also investigated the associations between DO2 and other variables thought to relate closely to it, including VO2, SaO2, SvO2, Sa‐vO2, mean arterial blood pressure (MABP), and SVR.

Methods

Patient Population

We studied all patients undergoing S1P for HLHS at Boston Children's Hospital between September 2012 and March 2015 (n=56) in this study. This period included 2 eras: prior to and following implementation of the treatment protocol described below. A subset of these, 21 patients (38%), were enrolled in a contemporaneous, prospective, observational study of oxygen transport parameters called Oxygen Consumption‐Based Assessments of Hemodynamics in Newborns (OxyCAHN). Patients in this study were treated according to the standard of care during their respective era but additionally underwent continuous monitoring of oxygen consumption. Practitioners were blinded to this measurement, which was used to provide a mechanistic understanding of protocol effects on oxygen consumption, systemic blood flow, and systemic vascular resistance. No treatments were altered based on observations made during this study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Boston Children's Hospital, and the guardians of all participants gave consent to participation.

In January 2014 our program implemented a program‐wide treatment protocol for neonates with HLHS focused on lowering SVR in the acute period following S1P. As a comparison, we studied the oxygen transport parameters of a convenience sample (n=6) of neonates with d‐transposition of the great arteries with intact ventricular septum (dTGA/IVS) undergoing an arterial switch operation (ASO).

Programmatic Changes

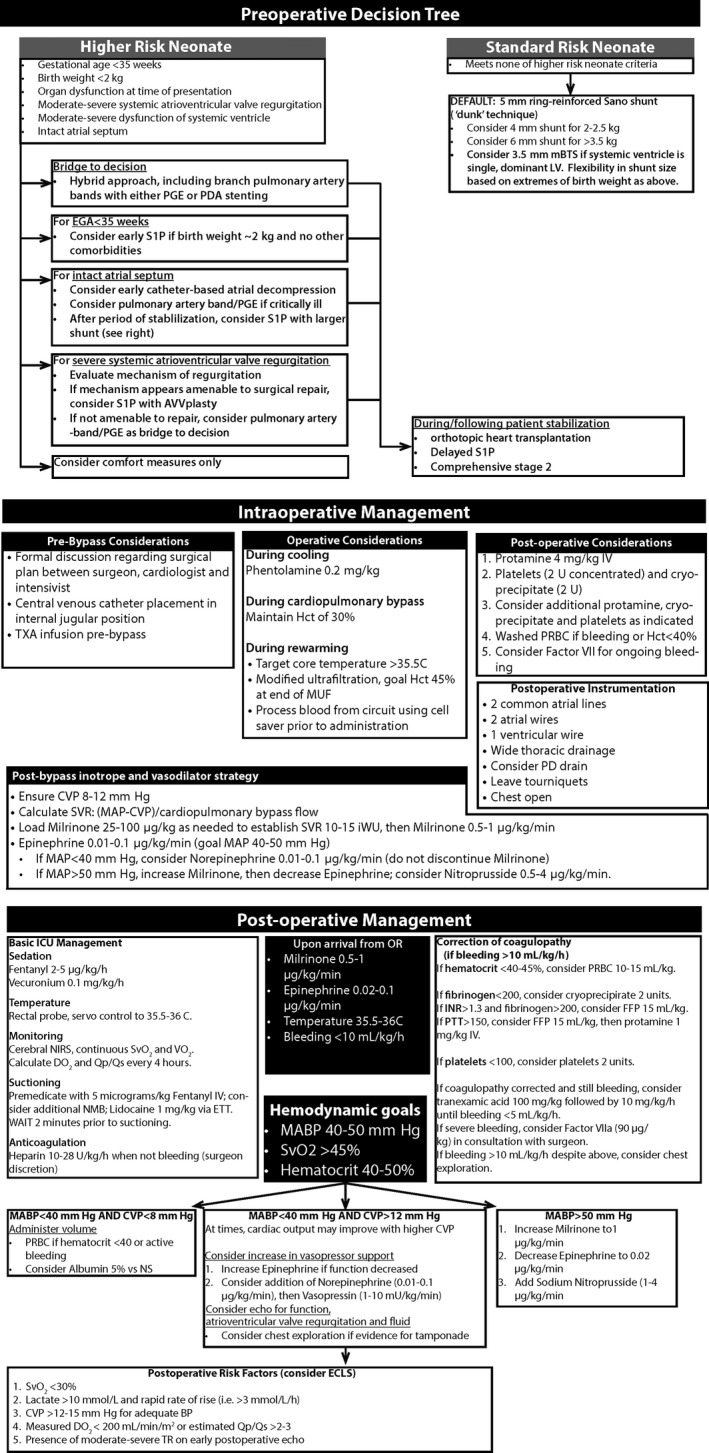

The treatment protocol was developed following an extensive literature review, personal communication with experts at several other congenital heart disease programs, and a series of multidisciplinary meetings. Implementation of the protocol took place through program‐wide and then discipline‐specific educational meetings (including cardiac surgery, cardiac anesthesia, perfusion, respiratory care, cardiac intensive care physician and nursing) as well as just‐in‐time training for ICU staff. As outlined in Figure 1, the protocol included preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative considerations.

Figure 1.

Details of the treatment protocol, including salient preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative features of the HLHS treatment algorithm, implemented in January 2014. AVVR indicates atrioventricular valve regurgitation; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; CVP, central venous pressure; DO 2, systemic oxygen delivery; ECLS, extracorporeal life support; EGA, estimated gestational age; ETT, endotracheal tube; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; MAP/MABP, mean arterial blood pressure; mBTS, modified Blalock‐Taussig shunt; MUF, modified ultrafiltration; OHT, orthotopic heart transplantation; PAB, pulmonary artery band; PD, peritoneal dialysis; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PGE, prostaglandin E1; PRBC, packed red blood cells; Qp/Qs, ratio of pulmonary to systemic blood flow; S1P, stage 1 palliation; SvO2, systemic venous oxyhemoglobin saturation; TR, tricuspid valve regurgitation; TXA, tranexamic acid; VO 2, oxygen consumption.

Shunt Type

Our protocol utilized a ring‐reinforced, transmural (“dunked”) GoreTex RVPAS9 in all neonates with HLHS whom we classified as standard risk. The size of the conduit was stratified by body weight.

Anesthetic Considerations

Prior to the operation, all patients were intubated with a cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT; to prevent leak around the ETT) and instrumented with a central venous catheter with the tip positioned ~1 cm above the junction of the superior vena cava and right atrium confirmed by chest radiograph. All patients received phentolamine and methylprednisolone during cooling on cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Infants received a perfusion strategy that maximized the use of regional perfusion over deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA),18 pH stat acid‐base correction,19 goal hematocrit of 35%,20 and modified ultrafiltration, although all of these practices were standard prior to protocol implementation as well. Collected erythrocytes were washed prior to readministration.21 The protocol specified that all patients leave the operating room with an open sternum and standard instrumentation.

Postoperative Volume, Vasodilator, and Inotrope Strategy

During weaning from CPB, target central venous pressure (CVP) was 8 to 12 mm Hg. SVR was estimated during weaning from CPB as (MABP – CVP)/(indexed CPB flow), and the goal was 12 iWU; this assumed native cardiac output to be negligible in the early phases of weaning from CPB. Prior to weaning from CPB, a loading dose of milrinone (25‐100 μg/kg, titrated to the goal SVR at a CI of 2 L/[min·m2]) was administered, and an infusion subsequently initiated (0.25‐1 μg/[kg·min]). An infusion of milrinone was continued in the intensive care unit through the time of extubation, and epinephrine was used as the primary inotrope. Clinical responses to hypotension (defined as MABP<40 mm Hg) were specified as follows: if the CVP was <8 to 10 mm Hg, volume was administered; otherwise, an epinephrine infusion was initiated or increased if DO2 was low, or a short‐acting vasoconstrictor (eg, norepinephrine or arginine vasopressin) was added to reverse excessive vasodilation.22 MABP in excess of 50 mm Hg was treated with either an increase in the milrinone infusion or through the addition of a short‐acting arterial vasodilator (ie, sodium nitroprusside).

Intensive Care Considerations

Because it has been shown that acute elevations in SVR cause hemodynamic instability,6 infants were sedated with a fentanyl infusion, and neuromuscular blockade was maintained through chest closure to minimize fluctuations in SVR during the early postoperative period. Prior to suctioning, patients were premedicated with a narcotic bolus and occasionally intratracheal lidocaine instillation. Body temperature was servoregulated within a narrow range (35.5°C to 36°C). The repletion of coagulation products was protocolized based on coagulation testing. Once bleeding was minimal, anticoagulation was initiated using an infusion of unfractionated heparin infusion titrated to a target anti‐Xa activity level. The use of extracorporeal life support and timing of chest closure were determined by the clinical team.

Measures of Oxygen Transport and Hemodynamics

Oxygen Consumption

In patients enrolled in the OxyCAHN study, oxygen consumption (VO2) was continuously measured using a commercially available device (Compact Gas Module, E‐COVX, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) fitted with a pediatric spirometry kit (part number 8002718). The device utilizes a sidestream, breath‐by‐breath technique and a paramagnetic oxygen analyzer. It has been previously used in infants and children with congenital heart disease for this purpose.23

Arterial and Venous Oxyhemoglobin Saturations

In all patients, SaO2 and SvO2 were obtained by co‐oximetry on blood sampled from the arterial or central venous line. All tests were run as clinically indicated in the institution's core lab. In addition, OxyCAHN study patients received oximetric venous catheters (4.5 French, PediaSat, Edwards LifeSciences, Irvine, CA) for continuous central venous oxyhemoglobin monitoring.

Oxygen Transport Parameters

SaO2, SvO2, and hemoglobin were abstracted from the medical record and converted into a running average for the purpose of instantaneous SBF measurements. SBF was calculated using the Fick method, and DO2 and SVR were calculated based on calculated SBF, MABP, and CVP. Because of the impact of unrecognized pulmonary vein desaturation (which we did not measure) on the calculation of Qp/Qs ratio,24 we elected not to examine this variable.

Calculation of Cumulative Oxygen Debt

Cumulative oxygen debt has been previously described as the cumulative difference between preoperative and postoperative VO2 over time.25, 26 Baseline VO2 was measured in each study patient in the operating room under general anesthesia and prior to the institution of CPB or hypothermia. For each postoperative hour, oxygen deficit was calculated as the difference between the median VO2 for that hour and the baseline VO2. At each time point, cumulative oxygen debt was calculated as the sum of all hourly oxygen deficit values (whether positive or negative) between the time that CPB was discontinued and that hour.25

Data Handling

Vital sign parameters were streamed from the bedside monitor to a central server, where data were stored in 5‐second intervals and subsequently exported for further analysis (T3 Data Collection and Analytics Software System, Etiometry, Inc, Boston, MA); these parameters included MABP, CVP, heart rate (HR), and pulse oximetry (SpO2). VO2, tidal volume, and other spirometry data were stored separately on a bedside computer in 5‐second intervals (S5 Collect Software, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). Laboratory data, including SaO2, SvO2, hemoglobin, and serum lactic acid, as well as anthropomorphic and echocardiographic measurements, pleural drainage volumes, blood product administration (including red blood cells, platelets, cryoprecipitate, fresh frozen plasma, and albumin), inotrope and vasoactive scores, ventilator and intensive care unit lengths of stay, and survival were abstracted from the medical record. Care was taken to match time stamps between data sources. Inotrope score (IS) was calculated as dopamine (μg/[kg·min])+dobutamine (μg/[kg·min])+100×epinephrine (μg/[kg·min]).27 The vasoactive inotropic score (VIS) was calculated as IS+100×norepinephrine (μg/[kg·min])+10×milrinone (μg/[kg·min])+10 000×vasopressin (U/[kg·min]).28, 29

The following techniques were applied to remove artifactual values from continuous measurements. VO2 values in which the measured tidal volume was 0 or exceeded 30 mL/kg body weight (representing artifact which can occur due to condensation in spirometry tubing) were excluded from analysis, as VO2 measurements are dependent on accurate spirometry. Intermittent measures of SaO2, SvO2, and hemoglobin were converted into a “best estimate” rolling average, which assumed a constant rate of change between measured values. SBF, DO2, and SVR values were then calculated for each 5‐second interval and downsampled to median hourly values (which removed artifact due to movement and line entry; MatLab version 2014b, Mathworks, Natick, MA). Relevant data were excluded during times when patients were supported with extracorporeal mechanical circulatory support (n=3) or did not have a central venous catheter appropriately positioned to permit sampling of systemic venous return (n=3). Descriptive statistics regarding the time spent within specified blood pressure ranges were performed on the primary data (every 5 seconds).

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were presented as mean±standard deviation or median with interquartile ranges (25th%, 75th%).

Variables between pre‐ and postintervention groups were compared by chi‐squared analysis or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. Differences in hemodynamic variables over time and between the pre‐ and postintervention groups were assessed using a mixed‐effects linear regression model. We examined for effect of group after controlling for time (linear and cubic terms) and random effects from subjects. We also included a group and time interaction term in the model when the interaction was significant. We present regression coefficients and P values for hemodynamic variables assessed in the mixed‐effects linear models. The models compared the postintervention group relative to the preintervention group, with a positive regression coefficient indicating a higher value in the postintervention group. We tested the association of DO2 with commonly followed hemodynamic variables using a restricted cubic spline regression. Models including random effects of time in addition to treatment group did not change estimates in a significant way, so results are adjusted for effects of treatment group only. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. Analyses were conducted using Stata 14.0 (College Station, TX) and IBM SPSS statistics software (v 21.0, Armonk, NY). All graphs were created in GraphPad Prism (version 6.0, LaJolla, CA).

Results

Patient Characteristics

During the study period, S1P was performed for HLHS in n=32 infants prior to and n=24 infants following implementation of the treatment protocol. There were no significant differences in birth weight, gestational age, Apgar scores, anatomic diagnosis, echocardiographic dimensions, or in the incidence of tricuspid valve regurgitation, aortic atresia, or right ventricular dysfunction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Preimplementation (n=32) | Postimplementation (n=24) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled in OxyCAHN study, n (%) | 10 (31) | 11 (46) | 0.28 |

| Age at operation, days | 3.5 [2.3, 5] | 4.5 [3, 6] | 0.07 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 22 (69) | 17 (71) | 1.0 |

| Birth weight, g | 3007±445 | 3221±441 | 0.08 |

| Gestational age | |||

| <38 weeks | 6 (19) | 4 (17) | 1.0 |

| Mean, weeks | 38.7±1.2 | 38.4±1.7 | 0.53 |

| Apgar scores | |||

| At 1 minute | 8 [7, 8] | 8 [7, 8] | 0.75 |

| At 5 minutes | 9 [8, 9] | 8 [8, 9] | 0.55 |

| Anatomical diagnosis, n (%) | 0.44 | ||

| Aortic atresia, mitral atresia | 13 (41) | 6 (25) | |

| Aortic atresia, mitral stenosis | 7 (22) | 5 (21) | |

| Aortic stenosis, mitral stenosis | 12 (38) | 12 (50) | |

| Aortic stenosis, mitral atresia | 0 | 1 (4)a | |

| Echocardiographic findings | |||

| Lateral mitral valve, cm | 0.64±0.16 | 0.64±0.19 | 0.96 |

| Ascending aorta, cm | 0.37±0.22 | 0.41±0.22 | 0.47 |

| Indexed LVEDV, mL/m2 | 15.2 [5.9, 23.4] | 16.9 [11.8, 33.2] | 0.40 |

| Moderate‐to‐severe TR, n (%) | 1 (3) | 2 (8) | 0.57 |

| Moderate‐to‐severe RV dysfunction, n (%) | 3 (9) | 2 (8) | 1.0 |

Plus‐minus values represent means±SD. Bracketed values follow median and represent interquartile range. Parentheses represent percentage of cohort. LVEDV indicates left ventricular end‐diastolic volume; TR, tricuspid valve regurgitation; RV, right ventricular.

This patient had mitral atresia, aortic stenosis, and a ventricular septal defect.

Intraoperative and Postoperative Characteristics

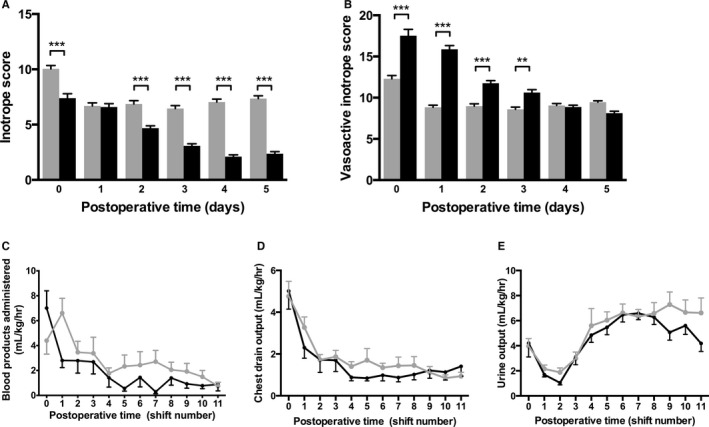

During the study period, a majority of patients received an RVPAS. In order to decrease ventricular volume load, n=5 patients received a valved homograft (cadaveric saphenous vein) placed as the RVPAS. For unclear reasons (but likely of importance), the mean duration of aortic cross‐clamping (mean 121 vs 92 minutes, P<0.001), of regional perfusion (mean 87 vs 69 minutes, P=0.005) and DHCA (mean 23 vs 9 minutes, P<0.001) were significantly lower following protocol implementation (Table 2). As expected, significantly more patients received a loading dose of milrinone in the operating room (9% vs 100%, P<0.001) and had a significantly lower IS and higher VIS in the postoperative period following implementation. There were no significant differences in postoperative pleural tube drainage, blood product administration, or urine output between the groups (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Operative and Postoperative Characteristics

| Preimplementation (n=32) | Postimplementation (n=24) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical procedure | 0.03 | ||

| 4 mm Sano | 3 (9) | 0 | |

| 5 mm Sano | 20 (63) | 14 (58) | |

| 6 mm Sano | 5 (16) | 4 (17) | |

| 3.5 mm modified BT shunt | 4 (13) | 1 (4) | |

| Saphenous vein RV‐PA graft | 0 | 5 (21) | |

| Operative times, minutes | |||

| Total cardiopulmonary bypass | 163±32 | 177±47 | 0.18 |

| Cross‐clamp | 121±29 | 92±32 | <0.001 |

| Regional perfusion | 87±21 | 68.7±26 | 0.005 |

| Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest | 23 [14, 37] | 8.5 [5, 15] | <0.001 |

| Mean hematocrit on CPB, % | 33.5±6.3 | 34.8±5.5 | 0.07 |

| Postoperative course and clinical outcomes | |||

| Incidence of CPR | 8 (25) | 1 (4) | 0.04 |

| Incidence of ECMO in ICU | 8 (25) | 1 (4) | 0.04 |

| Incidence of ECMO in OR | 1 (3) | 3 (13) | 0.18 |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation, days | 10 [7, 17] | 10.5 [7.3, 17.8] | 0.69 |

| Duration of ICU length of stay | 15.5 [11.3, 23.8] | 18 [13.3, 24.5] | 0.41 |

| Incidence of delayed sternal closure | 28 (88) | 24 (100) | 0.13 |

| Time to sternal closure, days | 5.8±5.4 | 7.0±5.5 | 0.45 |

| Survival to hospital discharge | 28 (88) | 23 (96) | 0.38 |

Plus‐minus values represent means±SD. Bracketed values follow median and represent interquartile range. Parentheses represent percentage of cohort. BT shunt indicates Blalock‐Taussig shunt; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU, intensive care unit; RV‐PA, right ventricular to pulmonary artery.

Figure 2.

A, The inotrope score, which reflects the doses of dopamine, dobutamine, and epinephrine, was significantly higher prior to protocol implementation. B, The vasoactive inotrope score, which additionally reflects the use of milrinone, norepinephrine, and vasopressin, was significantly higher following protocol implementation. C, The volume of blood products administered was similar between groups, as were chest drain output (D) and urine output (E) per 12‐hour shift. Gray bars, lines, dots, and error bars reflect preimplementation data (n=32); black represents postimplementation data (n=24). Data are means, errors are SEM. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01.

Differences in Postoperative Hemodynamics and Clinical Outcomes

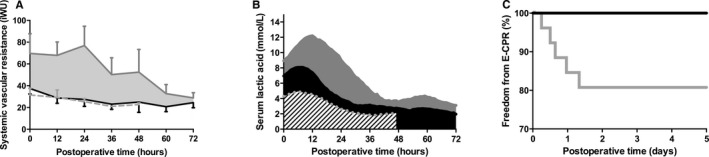

Following implementation of the algorithm, SVR was significantly lower (P=0.01), as was serum lactate (P<0.001) (Figure 3). These differences remained significant when corrected for durations of CPB, aortic cross‐clamping, and DHCA. SvO2 was on average 10 percentage points higher (P<0.001), and the Sa‐vO2 difference significantly lower (P<0.001), following protocol implementation in the early postoperative period, differences that diminished over time. Although not statistically significant, SBF was on average 0.53±0.32 L/(min·m2) higher (P=0.09), and DO2 was 70.1±53.2 mL/(min·m2) (P=0.19) higher in the first 72 hours following protocol implementation (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Patients treated following implementation of the protocol exhibited lower systemic vascular resistance (P=0.02, A), lower serum lactic acid levels (P<0.001, B) and a lower incidence of CPR requiring extracorporeal life support (E‐CPR, P=0.02, C) compared to those treated prior to the algorithm. A, Because SVR was calculated only in patients with measured oxygen consumption, A includes n=10 patients in the preimplementation group (solid gray line), n=11 patients in the postimplementation group (solid black line), and a convenience sample of dTGA patients (n=6, dotted gray); data are means, error are SEM. B and C, Gray lines, bars, and error bars reflect preimplementation data (n=32); black represents postimplementation data (n=24), and stripes represent dTGA patients (n=6).

Table 3.

Comparison of Hemodynamic Variables During the First 72 Postoperative Hours Prior to and Following Implementation of the Treatment Algorithm

| Variable | N | P Value | Magnitude of Algorithm Effectsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference at 0 Hours (95% CI)b | Difference at 36 Hours (95% CI)b | Difference at 72 Hours (95% CI)b | |||

| Mean Difference at Hours 0 to 72 (95% CI)f | |||||

| SBF, L/(min·m2) | 795 | 0.09 | 0.53 (0.1, 1.1) | ||

| iDO2, mL/(min·m2) | 795 | 0.19 | 70.1 (−34.2, 174.5) | ||

| iSVR, iWUc | 763 | 0.01 | −66 (−115, −16) | −41 (−83, 0.9) | −16 (−66, 35) |

| iVO2, mL/(min·m2) | 880 | 0.22 | 21.61 (17.69) | ||

| COD, L/m2 | 1306 | 0.56 | 54.1 (−129.6, 239.5) | ||

| Mean BP, mm Hge | 3534 | <0.001 | −6 (−8, −4) | −4 (−6, −2) | −2 (−4, 0.2) |

| CVP, mm Hg | 3499 | 0.13 | −0.9 (−2.0, 0.2) | ||

| Heart rate, bpm | 3538 | 0.84 | −0.5 (−5.4, 4.3) | ||

| SaO2 (%)d | 3760 | 0.54 | 0.1 (−3, 4) | 0.1 (−3, 4) | −1 (−5, 3) |

| SvO2 (%)e | 3182 | <0.001 | 10 (4, 16) | 6 (0, 11) | 1 (−5, 7) |

| AVO2 diff (%)e | 3160 | <0.001 | −8 (−12, −4) | −5 (−9, −1) | −2(−6, 1.5) |

| Temperature, °C | 3069 | 0.27 | 0.2 (−0.1, 0.4) | ||

| Lactate, mmol/Le | 1246 | <0.001 | −3.4 (−5.1, −1.7) | −1.8 (−3.5, −0.1) | −0.2 (−2.1, 1.6) |

Model adjusted for nonlinear effect of time and random variability at a subject level. AVO2 diff indicates arteriovenous oxyhemoglobin difference; bpm, beats per minute; COD, cumulative oxygen debt; CVP, central venous pressure; iDO2, indexed systemic oxygen delivery; iSVR, indexed systemic vascular resistance; iVO2, indexed oxygen consumption; N, number of observations; SaO2, arterial oxyhemoglobin concentration; SBF, systemic blood flow; SvO2, venous oxyhemoglobin concentration.

Between‐group comparisons are post‐ minus preimplementation values, such that positive values represent higher values postimplementation and negative values represent lower values postimplementation.

When differences between groups differed significantly over time (ie, P<0.10 for the time interaction), between‐group differences are displayed at postoperative hours 0, 36, and 72.

P value for group and time interaction P=0.08.

P value for group and time interaction P=0.002.

P value for group and time interaction P<0.001.

When between‐group differences were not different over time, the mean between‐group difference is displayed.

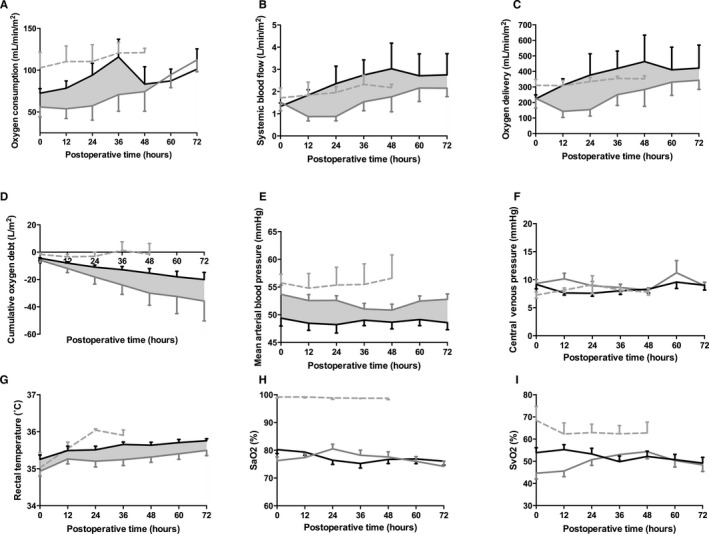

There were no composite between‐group differences in MABP, CVP, rectal temperature, or SaO2 (Figure 4). However, following protocol implementation, patients exhibited MABP>50 mm Hg for a lower proportion of time (68% [59% to 77%] vs 44% [31% to 56%], P=0.002). MABP was <35 mm Hg a similar proportion of time (0.2% [0.1% to 0.3%] vs 0.6% [0% to 1%], P=0.64) following protocol implementation. No patients in the OxyCAHN study experienced any adverse events (eg, tracheal tube occlusion) attributable to measurement of VO2.

Figure 4.

Oxygen consumption (A), systemic blood flow (B), systemic oxygen delivery (C), cumulative oxygen debt (D), mean arterial blood pressure (E), central venous pressure (F), rectal temperature (G), arterial (H, SaO2) and venous (I, SvO2) oxyhemoglobin saturations from patients prior to (gray) and following (black) implementation of the treatment algorithm surrounding the S1P. A through D, Oxygen consumption and its dependent variables are shown for all patients in the OxyCAHN study (n=10 pre‐ and n=11 postimplementation). E through I, n=32 pre‐ and n=24 postimplementation. A convenience sample (n=6, dotted gray) of infants undergoing ASO for dTGA/IVS is provided for comparison. Data are means, errors are SEM. P values, β, and standard errors for these variables are listed in Table 3.

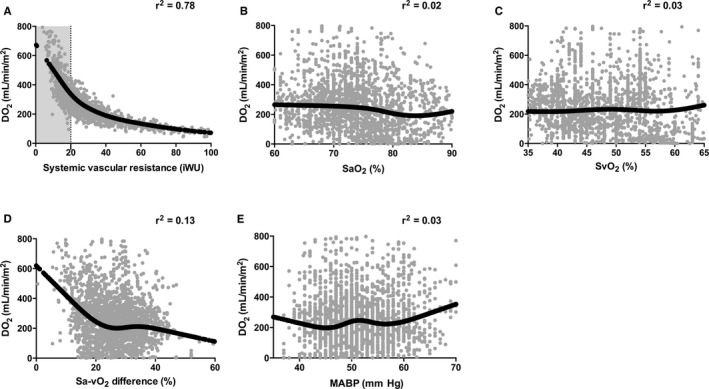

DO2 was inversely and nonlinearly related to SVR (r2=0.78, Figure 5), with the greatest DO2 occurring at an SVR below 20 iWU. The associations between DO2 and SaO2 (r2=0.02), SvO2 (r2=0.03), Sa‐vO2 difference (r2=0.13), and MABP (r2=0.03) were not as strongly correlated.

Figure 5.

Relationship of systemic oxygen delivery to (A) systemic vascular resistance, (B) arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation (SaO2), (C) venous oxyhemoglobin saturation (SvO2), (D) arteriovenous oxyhemoglobin saturation (Sa‐vO2) difference, and (E) mean arterial blood pressure for all patients studied in the OxyCAHN study (n=21). Data are hourly median values, black lines represent median spline through predicted values for DO 2. Adjusted r2 is shown for each model. Note that r2 values are not adjusted for repeated measures. MABP indicates mean arterial blood pressure.

Clinical Outcomes

The incidence of CPR requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (E‐CPR) in the early postoperative period was significantly lower following protocol implementation (P=0.02, log rank test, Figure 3C). The time to sternal closure, duration of mechanical ventilation, and ICU length of stay were similar between groups (Table 2).

Discussion

We report the effects of a standardized approach to the management of infants following S1P on oxygen delivery parameters and clinical outcomes. Specifically, we found that a milrinone‐based vasodilator protocol decreased SVR without an increased incidence of serious hypotension (MABP<35 mm Hg), decreased lactate production, and decreased the incidence of postoperative cardiac arrest, changes that persisted when corrected for differences in CPB times. Measurement of VO2 in study patients permitted quantification of DO2 and SVR and was not associated with adverse events. Calculated DO2 was not reflected in commonly measured surrogate markers, including SaO2, SvO2, Sa‐vO2, or MABP. The relationship between DO2 and SVR was inverse and nonlinear, with the greatest DO2 occurring at an SVR below 20 iWU.

Historically, management of DO2 was accomplished through manipulation of pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), including decreased fractional inspired oxygen, hypoventilation, or even the addition of carbon dioxide and nitrogen into inspired gases. These efforts proved to be of marginal utility because (1) the systemic‐to‐pulmonary shunt is typically the resistor of highest magnitude and is mechanical and fixed in nature, and (2) SVR is an order of magnitude higher than PVR, such that even when effective, manipulations in PVR are too small to impact DO2. More recently, several groups have described the use of systemic vasodilatory strategies to optimize DO2, demonstrating a narrowing of the Sa‐vO2 difference and decreased incidence of sudden circulatory collapse in the early postoperative period following S1P.4 These groups utilized a long‐acting, irreversible α‐receptor antagonist, phenoxybenzamine, to create a pharmacologic sympathectomy for the minimization of SVR. Although this strategy has been described to be safe, we chose a vasodilatory strategy that primarily employed the use of milrinone and sodium nitroprosside without phenoxybenzamine as an alternative approach to create a titratable vasodilatory milieu in the early postoperative period. We protocolized (as others have described22) the response to common hemodynamic profiles, including guidelines for volume administration and the addition of other vasoactive agents. We specified that the milrinone infusion be continued even in the setting of hypotension, adding short‐acting vasoconstrictors to more finely titrate SVR. This strategy did not increase the incidence of hypotension, and resulted in significantly lower SVR, lower serum lactate levels and a lower incidence of E‐CPR, all consistent with improved DO2. It should be noted that despite these improvements, we did not identify other clinical benefits such as time to sternal closure, duration of mechanical ventilation, or CICU LOS. Although it may be expected that these important factors be impacted by improved DO2, other clinical factors (eg, sedation practices, fluid, nutrition, and diuretic management) may in fact be dominant and should be the subject of future studies.

The methods for measuring VO2 in neonates have been established by several groups.17, 30 Although the value of measuring VO2 using mass spectroscopy–based devices is well established,17, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 the practice has not been widely adopted, possibly due to the impractical nature of these devices. We explored the use of a commercially available breath‐by‐breath system that can integrate seamlessly with existing ventilators to continuously measure VO2. We noted 2 practical limitations to the use of this system. The first was the accumulation of condensed water from the humidified ventilator circuit within the spirometry tubing, which altered tidal volume and VO2 measurements. Study personnel and bedside providers addressed this problem by flushing the tubing with air or replacing the sensor tubing when it occurred. Erroneous data were easily identified by post hoc screening for artifactual tidal volume readings (ie, >30 mL/kg expired tidal volume) and eliminating all respiratory variables (including VO2) at those time points. In addition, we noted VO2 measurements were often absent when the respiratory rate exceeded 45 breaths per minute, although this was a minority of measurements. Finally, we noted that despite its described use in neonates,23 when VO2 decreased below 10 mL/min, the values measured by this device were at times highly variable between breaths. This was likely due to the narrow difference between the oxygen content in inspired and expired gas under those circumstances. In the future, improvements in the technology are needed to address these shortcomings. Nonetheless, the composite VO2, SBF, and DO2 data in the postintervention group are consistent with those described by Li and colleagues32, 33, 35 and Mackie et al36 using alternative technologies.

We noted a striking relationship between DO2 and SVR. A similar relationship between these 2 variables has been demonstrated in single‐ventricle patients at several months of age (eg, in anticipation of the Glen or superior cavopulmonary anastamosis).37 In that setting SVR ranged between 12 and 35 iWU, with a steep increase in DO2 occurring at SVR below 12 iWU. In the early postoperative period Li also described a similar relationship between DO2 and SVR in infants primarily undergoing S1P with a mBTS.33

Finally, we also noted a poor correlation between variables that are commonly used to assess DO2, including SaO2 and MABP. Classically, the adequacy of DO2 has been assessed using SvO2, which reveals vital information regarding tissue oxygen delivery and correlates with outcomes. In a case series of 116 infants following S1P, postoperative SvO2 was higher in infants with uncomplicated survival compared with survivors with complications (including the need for CPR or ECMO), and survivors with complications had higher SvO2 values than those who sustained early mortality.38 Further, an SvO2 below 30% has been associated with a significantly increased incidence of anaerobic respiration following S1P.14 There likely exists a threshold value of SvO2 below which there is no meaningful delivery of oxygen to tissue.39 As a consequence, SvO2 and Sa‐vO2 difference in isolation may not necessarily be representative of tissue oxygen delivery in all circumstances. In addition to sampling error (intrinsic to the presence of a common atrium) and measurement error, SvO2 measurement (and by proxy, the Sa‐vO2 difference) in isolation may be misleading in several circumstances. Because SvO2 reflects tissue oxygen tension, there is functionally a lower limit of tissue hypoxia and therefore of SvO2 in surviving patients. Further, in critically ill postoperative patients, low oxygen delivery, tissue edema,40 endothelial dysfunction, altered erythrocyte deformability,41, 42 and mitochondrial dysregulation may lead to cellular dysoxia (ie, impaired oxygen uptake). This may cause a decrease in measured VO2, a preserved (or even elevated) SvO2, anaerobic mitochondrial conditions, and the accumulation of tissue lactate. Thus, measuring VO2 and its use to calculate DO2 add a physiologically important variable that may add new information to the assessment of these infants.

Limitations

Several limitations to our study merit discussion. First, the intrinsic limitations of quantifying oxygen transport in the single‐ventricle circulation apply to our study. There is no place to sample truly mixed venous blood, such that several assumptions regarding regional and whole‐body perfusion are required. More importantly, gold standard techniques for the independent measurement of SBF (ie, ones that obviate dependence on VO2 measurement), including thermodilution or indicator dilution techniques, cannot be used in this circulation. Therefore, in the absence of direct flow measurement (eg, using flow probes on the reconstructed aorta or magnetic resonance techniques), the Fick principle is the only option for estimating SBF. The derivation of SVR and DO2 as dependent variables is unavoidable in that setting. Thus, our findings may be biased by the mathematical coupling that confounded studies of pathologic oxygen supply dependency.43 However, given the physiology of the single‐ventricle (ie, parallel) circulation, combined with the expected postoperative low‐cardiac‐output state that follows the S1P, it is not surprising that we found a striking relationship between DO2 and SVR in the early postoperative period. Second, because the device we used to measure VO2 required the post hoc removal of artifactual data points, real‐time calculations of DO2 and SVR are not currently possible. Future work to remove artifacts and to improve measurement accuracy during extremely low VO2 states will be important to the broad translation of this technique. Third, a minority of patients studied here were included in the OxyCAHN study, largely due to difficulty in obtaining consent for such a study prior to operation at a few days of life. Thus, our study was underpowered to detect differences between groups in oxygen transport measures (including DO2). Further, our study design does not allow for causal inferences. Fourth, we did not measure compliance with the protocol, including deviations and the reasons for them. Although patients treated with the protocol received significantly more vasodilators, the study was not designed to describe the relative importance of these and other differences between the groups, including the use of valved homografts to provide pulmonary blood flow. Each of these variables will be important to study in the future. Fifth, the shorter duration of cardiopulmonary bypass ischemic times in the postintervention group is an important confounder to these study results, although the differences in outcomes persist following adjustment for these factors. The cause of this difference is unclear to us, as there was little difference in the incidence of patients with aortic atresia, and little change in surgical case load or staffing; it perhaps represents a Hawthorne effect. Last, the short‐term duration of follow‐up precludes any conclusions relating the treatment protocol with long‐term neurodevelopment and survival outcomes.

Conclusions

The implementation of a standardized, milrinone‐based vasodilator protocol effectively lowered SVR, decreased lactate accumulation, and decreased the incidence of E‐CPR following S1P without excessive hypotension. The translation of these short‐term improvements to long‐term outcomes will be important.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported through funding from the Gerber Foundation (Kheir), the Boston Children's Heart Foundation (Kheir), a Boston Children's Hospital Pilot Research Grant (Kheir), and the Strategic Investment Fund at Boston Children's Hospital Heart Center.

Disclosures

During the study period, the authors (Kheir and Walsh) entered into an agreement with General Electric for the use of 2 ventilators and spirometry modules. However, the equipment was not received during the study period. General Electric did not participate in study design or data collection, did not provide funding for the study, and did not review the manuscript prior to submission. The authors do not report any conflict of interest related to this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the physician, nursing, and respiratory therapy staff of the cardiac ICU for assistance with the OxyCAHN study, the cardiac anesthesia and perfusion staff for assistance with implementation of the algorithm, Matthew Tearle for assistance with MATLAB coding, Kathrine Black, Lauren Ruoss, Hua Liu, and Michael McManus for assistance with data collection, Dorothy Beke, Lindyce Kulik, and Patricia Lincoln for education of bedside nursing staff regarding the treatment algorithm, and Tom Kulik and Jane Newburger for an insightful review of the manuscript.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003554 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003554)

References

- 1. Norwood WI, Lang P, Hansen DD. Physiologic repair of aortic atresia‐hypoplastic left heart syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ohye RG, Sleeper LA, Mahony L, Newburger JW, Pearson GD, Lu M, Goldberg CS, Tabbutt S, Frommelt PC, Ghanayem NS, Laussen PC, Rhodes JF, Lewis AB, Mital S, Ravishankar C, Williams IA, Dunbar‐Masterson C, Atz AM, Colan S, Minich LL, Pizarro C, Kanter KR, Jaggers J, Jacobs JP, Krawczeski CD, Pike N, McCrindle BW, Virzi L, Gaynor JW; Pediatric Heart Network Investigators . Comparison of shunt types in the Norwood procedure for single‐ventricle lesions. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1980–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, Frommelt PC, Pearson GD, Mahle WT, Chen S, Dunbar‐Masterson C, Mital S, Williams IA, Ghanayem NS, Goldberg CS, Jacobs JP, Krawczeski CD, Lewis AB, Pasquali SK, Pizarro C, Gruber PJ, Atz AM, Khaikin S, Gaynor JW, Ohye RG; Pediatric Heart Network Investigators . Transplantation‐free survival and interventions at 3 years in the single ventricle reconstruction trial. Circulation. 2014;129:2013–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. De Oliveira NC, Ashburn DA, Khalid F, Burkhart HM, Adatia IT, Holtby HM, Williams WG, Van Arsdell GS. Prevention of early sudden circulatory collapse after the Norwood operation. Circulation. 2004;110(11 suppl 1):II133–II138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoffman GM, Tweddell JS, Ghanayem NS, Mussatto KA, Stuth EA, Jaquis RDB, Berger S. Alteration of the critical arteriovenous oxygen saturation relationship by sustained afterload reduction after the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tweddell JS, Hoffman GM, Fedderly RT, Berger S, Thomas JP, Ghanayem NS, Kessel MW, Litwin SB. Phenoxybenzamine improves systemic oxygen delivery after the Norwood procedure. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tweddell JS, Hoffman GM, Mussatto KA, Fedderly RT, Berger S, Jaquiss RDB, Ghanayem NS, Frisbee SJ, Litwin SB. Improved survival of patients undergoing palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome: lessons learned from 115 consecutive patients. Circulation. 2002;106:I82–I89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sano S, Ishino K, Kawada M, Arai S, Kasahara S, Asai T, Masuda Z‐I, Takeuchi M, Ohtsuki S‐I. Right ventricle–pulmonary artery shunt in first‐stage palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:504–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baird CW, Myers PO, Borisuk M, Pigula FA, Emani SM. Ring‐reinforced Sano conduit at Norwood stage I reduces proximal conduit obstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pigott JD, Murphy JD, Barber G, Norwood WI. Palliative reconstructive surgery for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;45:122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barnea O, Austin EH, Richman B, Santamore WP. Balancing the circulation: theoretic optimization of pulmonary/systemic flow ratio in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:1376–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barnea O, Santamore WP, Rossi A, Salloum E, Chien S, Austin EH. Estimation of oxygen delivery in newborns with a univentricular circulation. Circulation. 1998;98:1407–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yuki K, Emani S, DiNardo JA. A mathematical model of transitional circulation toward biventricular repair in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:618–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoffman GM, Ghanayem NS, Kampine JM, Berger S, Mussatto KA, Litwin SB, Tweddell JS. Venous saturation and the anaerobic threshold in neonates after the Norwood procedure for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1515–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoffman GM, Mussatto KA, Brosig CL, Ghanayem NS, Musa N, Fedderly RT, Jaquiss RDB, Tweddell JS. Systemic venous oxygen saturation after the Norwood procedure and childhood neurodevelopmental outcome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1094–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li J, Zhang G, Holtby HM, McCrindle BW, Cai S, Humpl T, Caldarone CA, Williams WG, Redington AN, Van Arsdell GS. Inclusion of oxygen consumption improves the accuracy of arterial and venous oxygen saturation interpretation after the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:1099–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li J, Bush A, Schulze‐Neick I, Penny DJ, Redington AN, Shekerdemian LS. Measured versus estimated oxygen consumption in ventilated patients with congenital heart disease: the validity of predictive equations. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1235–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rappaport LA, Wypij D, Bellinger DC, Helmers SL, Holmes GL, Barnes PD, Wernovsky G, Kuban KC, Jonas RA, Newburger JW. Relation of seizures after cardiac surgery in early infancy to neurodevelopmental outcome. Boston Circulatory Arrest Study Group. Circulation. 1998;97:773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. du Plessis AJ, Jonas RA, Wypij D, Hickey PR, Riviello J, Wessel DL, Roth SJ, Burrows FA, Walter G, Farrell DM, Walsh AZ, Plumb CA, del Nido P, Burke RP, Castaneda AR, Mayer JE Jr, Newburger JW. Perioperative effects of alpha‐stat versus pH‐stat strategies for deep hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass in infants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114:991–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shin'oka T, Shum‐Tim D, Jonas RA, Lidov HG, Laussen PC, Miura T, Du Plessis A. Higher hematocrit improves cerebral outcome after deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:1610–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cholette JM, Henrichs KF, Alfieris GM, Powers KS, Phipps R, Spinelli SL, Swartz M, Gensini F, Daugherty LE, Nazarian E, Rubenstein JS, Sweeney D, Eaton M, Lerner NB, Blumberg N. Washing red blood cells and platelets transfused in cardiac surgery reduces postoperative inflammation and number of transfusions: results of a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:290–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Oliveira NC, Van Arsdell GS. Practical use of alpha blockade strategy in the management of hypoplastic left heart syndrome following stage one palliation with a Blalock‐Taussig shunt. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2004;7:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seckeler MD, Hirsch R, Beekman RH, Goldstein BH. A new predictive equation for oxygen consumption in children and adults with congenital and acquired heart disease. Heart. 2015;101:517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Taeed R, Schwartz SM, Pearl JM, Raake JL, Beekman RH, Manning PB, Nelson DP. Unrecognized pulmonary venous desaturation early after Norwood palliation confounds Qp: Qs assessment and compromises oxygen delivery. Circulation. 2001;103:2699–2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Kram HB. Tissue oxygen debt as a determinant of lethal and nonlethal postoperative organ failure. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:1117–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Kram HB. Oxygen transport measurements to evaluate tissue perfusion and titrate therapy: dobutamine and dopamine effects. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:672–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wernovsky G, Wypij D, Jonas RA, Mayer JE, Hanley FL, Hickey PR, Walsh AZ, Chang AC, Castañeda AR, Newburger JW. Postoperative course and hemodynamic profile after the arterial switch operation in neonates and infants. A comparison of low‐flow cardiopulmonary bypass and circulatory arrest. Circulation. 1995;92:2226–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gaies MG, Gurney JG, Yen AH, Napoli ML, Gajarski RJ, Ohye RG, Charpie JR, Hirsch JC. Vasoactive–inotropic score as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in infants after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gaies MG, Jeffries HE, Niebler RA, Pasquali SK, Donohue JE, Yu S, Gall C, Rice TB, Thiagarajan RR. Vasoactive‐inotropic score is associated with outcome after infant cardiac surgery. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:529–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang AC, Kulik TJ, Hickey PR, Wessel DL. Real‐time gas‐exchange measurement of oxygen consumption in neonates and infants after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1369–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li J, Zhang G, McCrindle BW, Holtby H, Humpl T, Cai S, Caldarone CA, Redington AN, Van Arsdell GS. Profiles of hemodynamics and oxygen transport derived by using continuous measured oxygen consumption after the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:441–448.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li J, Zhang G, Benson L, Holtby H, Cai S, Humpl T, Van Arsdell GS, Redington AN, Caldarone CA. Comparison of the profiles of postoperative systemic hemodynamics and oxygen transport in neonates after the hybrid or the Norwood procedure: a pilot study. Circulation. 2007;116(11 suppl):I179–I187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li J. Systemic oxygen transport derived by using continuous measured oxygen consumption after the Norwood procedure—an interim review. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15:93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li J, Zhang G, Holtby H, Humpl T, Caldarone CA, Van Arsdell GS, Redington AN. Adverse effects of dopamine on systemic hemodynamic status and oxygen transport in neonates after the Norwood procedure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1859–1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li J, Zhang G, Holtby H, Guerguerian A‐M, Cai S, Humpl T, Caldarone CA, Redington AN, Van Arsdell GS. The influence of systemic hemodynamics and oxygen transport on cerebral oxygen saturation in neonates after the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:83–90, 90.e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mackie AS, Booth KL, Newburger JW, Gauvreau K, Huang SA, Laussen PC, DiNardo JA, del Nido PJ, Mayer JE Jr, Jonas RA, McGrath E, Elder J, Roth SJ. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled pilot trial of triiodothyronine in neonatal heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:810–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Migliavacca F, Pennati G, Dubini G, Fumero R, Pietrabissa R, Urcelay G, Bove EL, Hsia TY, de Leval MR. Modeling of the Norwood circulation: effects of shunt size, vascular resistances, and heart rate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2076–H2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tweddell JS, Ghanayem NS, Mussatto KA, Mitchell ME, Lamers LJ, Musa NL, Berger S, Litwin SB, Hoffman GM. Mixed venous oxygen saturation monitoring after stage 1 palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1301–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Francis DP, Willson K, Thorne SA, Davies LC, Coats AJ. Oxygenation in patients with a functionally univentricular circulation and complete mixing of blood: are saturation and flow interchangeable? Circulation. 1999;100:2198–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shah DM, Newell JC, Saba TM. Defects in peripheral oxygen utilization following trauma and shock. Arch Surg. 1981;116:1277–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reggiori G, Occhipinti G, De Gasperi A, Vincent J‐L, Piagnerelli M. Early alterations of red blood cell rheology in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:3041–3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Donadello K, Piagnerelli M, Reggiori G, Gottin L, Scolletta S, Occhipinti G, Boudjeltia KZ, Vincent J‐L. Reduced red blood cell deformability over time is associated with a poor outcome in septic patients. Microvasc Res. 2015;101:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hanique G, Dugernier T, Laterre PF, Dougnac A, Roeseler J, Reynaert MS. Significance of pathologic oxygen supply dependency in critically ill patients: comparison between measured and calculated methods. Intensive Care Med. 1994;20:12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]