Abstract

RNA editing by A-to-I deamination is the prominent co-/post-transcriptional modification in humans. It is carried out by ADAR enzymes and contributes to both transcriptomic and proteomic expansion. RNA editing has pivotal cellular effects and its deregulation has been linked to a variety of human disorders including neurological and neurodegenerative diseases and cancer. Despite its biological relevance, many physiological and functional aspects of RNA editing are yet elusive. Here, we present REDIportal, available online at http://srv00.recas.ba.infn.it/atlas/, the largest and comprehensive collection of RNA editing in humans including more than 4.5 millions of A-to-I events detected in 55 body sites from thousands of RNAseq experiments. REDIportal embeds RADAR database and represents the first editing resource designed to answer functional questions, enabling the inspection and browsing of editing levels in a variety of human samples, tissues and body sites. In contrast with previous RNA editing databases, REDIportal comprises its own browser (JBrowse) that allows users to explore A-to-I changes in their genomic context, empathizing repetitive elements in which RNA editing is prominent.

INTRODUCTION

A growing literature describes RNA editing as an essential co-/post-transcriptional process, whereby a genetic message is modified from the corresponding DNA template by means of substitutions, insertions and/or deletions (1). The deamination of adenosines (As) to inosines (Is) by the family of ADAR enzymes acting on double RNA strands is the prominent RNA editing event occurring in humans (2). A-to-I changes are pivotal for cellular homeostasis as attested by the association between RNA editing dysregulation and human disorders such as neurological/neurodegenerative diseases and cancer (3–5). RNA editing by A-to-I modification contributes to transcriptome and proteome expansion (6) and has several functional and regulatory implications, altering codon identity, creating or destroying splice sites and affecting base-pairing interactions in secondary and tertiary RNA structures (7,8).

The advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies has largely improved the computational detection of RNA editing events at genomic scale (9), revealing its pervasive nature in the human transcriptome. Recently, we have profiled RNA editing in six human tissues (brain, lung, muscle, heart, kidney and liver) from three individuals using high coverage directional RNAseq and whole genome sequencing (WGS) data (6). By our large survey, we identified more than 3 millions of A-to-I events differently distributed across six tissues, thus producing the first RNA editing atlas in humans (6). Despite these findings, many functional aspects of RNA editing are yet unknown and further investigations are needed to elucidate the dynamic regulation of editing sites. To shed light on potential functional roles of RNA editing, we have developed an ad hoc bioinformatics resource named REDIportal, comprising the largest and non-redundant collection of RNA editing events across 55 human body sites grouped in 30 tissues.

Currently, RNA editing events are annotated in three main databases: DARNED (http://darned.ucc.ie/) (10), RADAR (http://rnaedit.com/) (11) and REDIdb (http://srv00.recas.ba.infn.it/py_script/REDIdb/) (12,13). While the last is devoted to organellar RNA editing, DARNED provides information on A-to-I changes for human, mouse and fruit fly. However, it is not updated since 2013 and does not provide editing levels information. RADAR, instead, annotates A-to-I events in human, mouse and fly likewise DARNED and incorporates editing levels for 38% of stored positions, since based on a limited number of RNAseq samples and mainly from LCL cell lines that may not be optimal for RNA editing studies (6).

In contrast, REDIportal includes more than 4.5 millions of A-to-I changes obtained merging RNA editing positions from our Inosinome ATLAS (6) and RADAR database (11). This large and non-redundant collection of RNA editing sites has been employed to interrogate more than 2,500 GTEx RNAseq experiments from 55 body sites of 147 individuals for which WGS data are available. REDIportal allows the study of dynamic regulation of RNA editing contributing to elucidate its biological roles in physiological and pathological conditions. REDIportal annotates also a plethora of additional info and embeds a specific genome browser (JBrowse) to explore RNA editing events in their genomic context.

Our portal has been conceived to collect RNA editing events/levels from a huge amount of RNAseq data in order to create the largest repository and bioinformatics infrastructure for RNA editing.

Hereafter, we describe main REDIportal features including database architecture and content as well as source data for calling A-to-I events.

RNAseq DATA COLLECTION

RNA editing data stored in REDIportal derive from 2,660 RNAseq experiments in 150 human individuals. Of these, 2,642 RNAseqs originate from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project, the largest collection of high-throughput genomic data for studying gene expression in different normal tissues obtained from hundreds of individuals. Remaining 18 RNAseqs were produced in our lab and used to create the first RNA editing atlas in humans (6). Although the current GTEx release (v6) includes more than 8,500 RNAseq data, we selected only 2,642 experiments for which matched RNAseq and WGS data were available, allowing more reliable RNA editing calls.

RNAseq data used in REDIportal encompass 55 human body sites from 30 different tissues with an over-representation of brain, skin, blood and esophagus (Table 1). On average, there are 18 RNAseq data per individual and 50 million reads per experiment. The majority of RNAseq data derives from unstranded libraries of polyA enriched RNA (2×76 bp), while only 72 experiments are from libraries of total RNA preserving strand orientation (2×100 and 2×150 bp).

Table 1. Human tissues included in REDIportal.

| Tissue | N. Body Sites | N. RNAseq | Edited Sites | Tissue Specific Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adipose_Tissue | 2 | 139 | 908,329 | 13,906 |

| Adrenal_Gland | 1 | 48 | 387,832 | 1,203 |

| Bladder | 1 | 7 | 220,834 | 131 |

| Blood | 2 | 217 | 1,029,817 | 47,340 |

| Blood_Vessel | 3 | 226 | 838,529 | 8,014 |

| Brain | 13 | 332 | 2,145,092 | 660,647 |

| Breast | 1 | 49 | 630,966 | 2,919 |

| Cervix_Uteri | 2 | 11 | 302,369 | 232 |

| Colon | 2 | 78 | 551,758 | 1,870 |

| Esophagus | 3 | 224 | 832,760 | 6,066 |

| Fallopian_Tube | 1 | 5 | 214,108 | 542 |

| Heart | 2 | 123 | 680,059 | 37,996 |

| Kidney | 2 | 10 | 832,941 | 194,009 |

| Liver | 1 | 37 | 847,101 | 177,572 |

| Lung | 1 | 141 | 1,933,447 | 401,128 |

| Muscle | 2 | 138 | 432,518 | 15,795 |

| Nerve | 1 | 96 | 788,318 | 6,153 |

| Ovary | 1 | 34 | 574,445 | 2,432 |

| Pancreas | 1 | 63 | 476,566 | 3,783 |

| Pituitary | 1 | 22 | 461,319 | 2,708 |

| Prostate | 1 | 38 | 562,309 | 3,281 |

| Salivary_Gland | 1 | 10 | 276,682 | 184 |

| Skin | 3 | 266 | 941,851 | 13,572 |

| Small_Intestine | 1 | 12 | 294,924 | 398 |

| Spleen | 1 | 38 | 428,196 | 1,495 |

| Stomach | 1 | 65 | 436,741 | 642 |

| Testis | 1 | 68 | 711,769 | 13,528 |

| Thyroid | 1 | 106 | 961,407 | 14,512 |

| Uterus | 1 | 31 | 509,074 | 1,287 |

| Vagina | 1 | 26 | 472,882 | 906 |

For each tissue we report the number of body sites and explored RNAseq experiments, the amount of detected RNA editing sites and the number of tissue specific A-to-I changes. Tissue specific events are defined here as sites edited at non-zero level in a unique tissue.

GTEx datasets were downloaded from the database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP) with accession phs000424.v6.p1 in sra format and converted in standard fastq by means of fastq-dump program that is part of the SRA toolkit (http://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra).

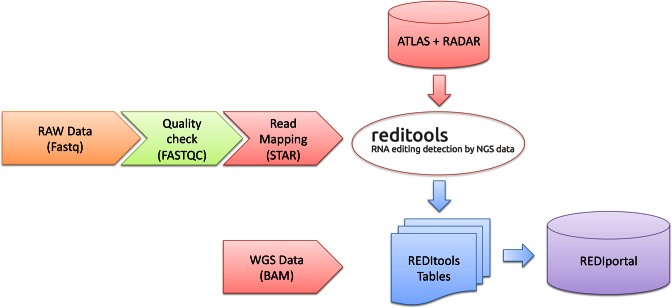

Fastq files were then mapped onto the complete human genome by STAR (14) and multiple read alignments were saved in sorted bam files (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Computational workflow used to load RNA editing sites in REDIportal. Raw data in Fastq format are quality checked by FASTQC and aligned onto the reference human genome by STAR (14). REDItools (15) are then used to interrogate multiple read alignments using a large collection of known RNA editing sites from ATLAS repository (6) and RADAR database (11). WGS data are finally included in REDItools tables and, in turn, stored in REDIportal.

RNA EDITING CALLING AND ANNOTATION

RNA editing events were obtained merging known positions from our ATLAS (6) repository and from RADAR database (11) (Figure 1). Both collections include A-to-I changes identified using rigorous computational pipelines (6,9). While RADAR comprises editing positions detected mainly in lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL), ATLAS incorporates A-to-I changes from six human tissues (brain, lung, liver, kidney, muscle and heart) in three different individuals. In addition, ATLAS positions were called using a combination of two computational strategies on strand oriented RNAseq reads (6). Initially, RNA editing events were detected using REDItools (15) and stringent filters, especially in case of positions falling in non-repetitive regions for which the RNA editing detection is challenging (6). Editing candidates not supported by homozygous genomic DNA, obtained by whole genome resequencing of the same individual, were excluded (6). Then, unaligned RNA reads were rescued through the pipeline described in Porath et al. (16) in order to detect RNA editing sites in hyper-edited reads.

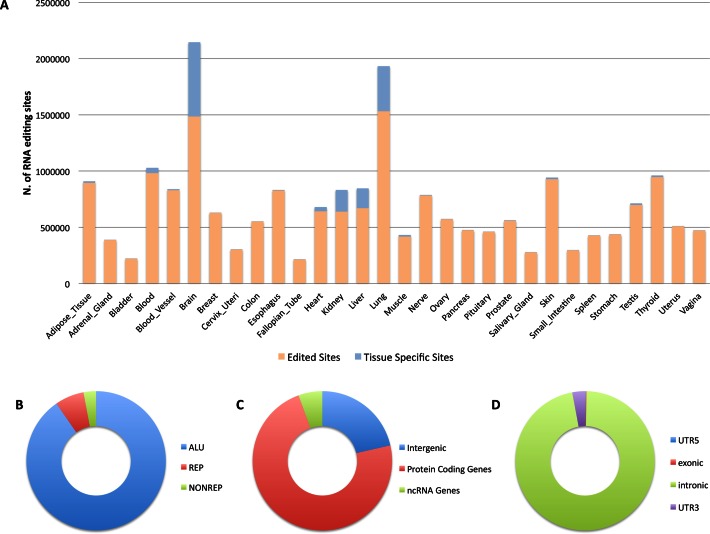

Merging ATLAS and RADAR positions yielded a comprehensive and non-redundant RNA editing catalogue comprising 4,668,508 sites. This huge collection was used to interrogate aligned RNAseq reads from GTEx project through REDItools, employing a large computational farm at the Italian National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN) that includes about 10,000 cores. An ad hoc script was finally applied to add genomic support from GTEx WGS data to exclude SNPs resembling editing events at transcript level (Figure 1). The number of detected RNA editing events per tissue group as well as the amount of tissue exclusive A-to-I changes are reported in Table 1 and graphically displayed in Figure 2A.

Figure 2.

RNA editing distribution along human tissues and a graphical overview of sites stored in REDIportal. A-to-I events collected in REDIportal derive from RNAseq data encompassing 55 human body sites grouped in 30 different tissues. The distribution of RNA editing events detected according to our computational workflow, depicted in Figure 1, are shown in (A) along tissue specific events (in blue). Here, tissue specific events are defined as sites edited at non-zero level in a unique tissue. RNA editing sites stored in REDIportal are classified in three main categories, shown in (B), depending on their location: (i) ALU, residing in Alu repetitive elements, (ii) REP, located in non-Alu repetitive elements and (iii) NONREP, placed in non repetitive regions. The vast majority of A-to-I changes occur in protein coding genes (73%) as shown in (C) and especially in intronic regions (D). In untranslated regions, RNA editing changes are more abundant in 3′ UTRs than in 5′ UTRs (D).

RNA editing sites were annotated using ANNOVAR (17) tool and the following databases: (i) RepeatMasker for repetitive elements; (ii) dbSNP (version 142) for genomic single nucleotide polymorphisms; (iii) Gencode (v19), Refseq and UCSC for gene and transcript annotations; (iv) PhastCons for conservation scores across 46 species and (v) RADAR and DARNED for known A-to-I changes. All repositories but RADAR and DARNED were downloaded from UCSC genome browser. RADAR and DARNED positions were obtained from corresponding web sites.

DATABASE CONTENT AND ARCHITECTURE

REDIportal collects 4,668,508 A-to-I editing sites in two main MySQL tables. The first table stores basic info including genomic positions, strand, genes and transcripts, SNP accessions and RepeatMasker elements. This table comprises also a binary string for a fast search of tissues and body sites in which each RNA editing position has been observed. The second table, instead, includes RNA editing levels per tissue and body site as well as RNAseq and WGS support.

In REDIportal, RNA editing positions are classified in three main categories depending on their location: (i) ALU, residing in Alu repetitive elements (4,218,154 sites), (ii) REP, located in non-Alu repetitive elements (314,370 sites) and (iii) NONREP, placed in non repetitive regions (135,984 sites). REP editing sites are mainly found in LINEs (49.8% of sites), LTR (22.6% of sites) and SINEs non-Alu (19.2% of sites) (Figure 2B).

The 82% of collected RNA editing events (3,844,437) occurs in 21,926 gene loci that, according to Gencode v19 annotations, represent the 38% of human genes. Of these, 7,390 are genes for non-coding RNAs, while 14,536 are protein coding genes and account for 72% of total annotated protein coding loci in Gencode. Remaining 824,071 (18%) A-to-I events, instead, are in intergenic genomic regions (Figure 2C).

A consistent fraction (73%) of RNA editing sites is located in protein coding genes and mainly in intervening sequences (3,286,779) since they are rich in Alu elements. More than 6,786 events are placed in coding sequences and, of these, 4,388 sites are nonsynonymous, altering the corresponding amino acid with potential functional consequences. In untranslated regions, RNA editing changes are more abundant in 3′ UTRs (100,399) than in 5′ UTRs (5,236) (Figure 2D).

The current REDIportal release comprises RNA editing events across 55 body sites grouped in 30 tissues. Among tissues, brain, lung, kidney and liver are those with the highest numbers of specific RNA editing sites (Table 1 and Figure 2A). Within the brain tissue group, cortex is the overrepresented body site in terms of exclusive RNA editing events.

WEB INTERFACE AND INTERROGATION

REDIportal is easily accessible through an ad hoc web interface developed in Bootstrap, a JavaScript framework including HTML, CSS and JavaScript code designed for creating responsive websites and web applications (http://getbootstrap.com/). Server side operations including MySQL querying and retrieval are performed in Python (v2.7.2) with the support of dedicated modules, such as MySQLdb (https://pypi.python.org/pypi/MySQL-python/1.2.5) for quick connections to MySQL server and mxTextTools (http://www.egenix.com/products/python/mxBase/mxTextTools/) for high-performance text manipulation.

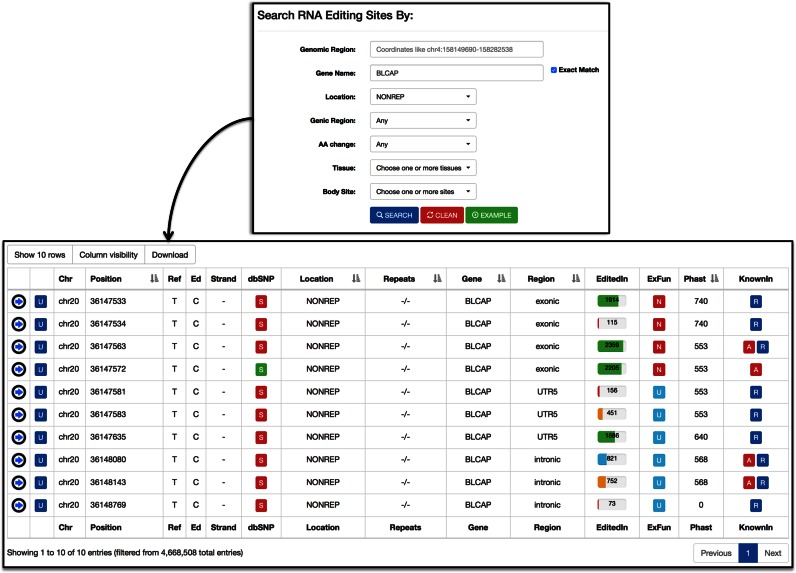

REDIportal allows RNA editing searches providing a genomic region, in the format chr:start-end, or a specific gene symbol, in combination with user-defined filters to restrict the number of retrieved sites to those of interest. Users can actually select the category of desired positions (ALU, NONREP or REP) or the genic region (UTR, exonic, intronic or intergenic) or the involvement in amino acid changes (synonymous or nonsynonymous). Furthermore, users can specify one or more tissues as well as one or more body sites (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Query and retrieval in REDIportal. Editing sites can be searched entering genome coordinates or gene symbols in combination with additional filters. In figure we show a query for editing positions occurring in non-repetitive elements (NONREP) of BLCAP gene. A-to-I sites found in REDIportal are displayed in a dynamic table with a variety of extra information such as: (i) a link to UCSC genome browser; (ii) the genomic position; (iii) the reference and edited nucleotide; (iv) the strand; (v) the dbSNP accession (if any); (vi) the editing location; (vii) the repeated element (if any); (viii) the gene symbol according to Gencode v19; (ix) the genic region; (x) the number of edited samples; (xi) the potential amino acid change; (xii) the PhastCons conservation score across 46 organisms; and (xi) a flag indicating in which database (ATLAS, RADAR or DARNED) is reported.

Retrieved sites are shown in a dynamic and sortable table automatically generated by means of DataTables (https://datatables.net/), a powerful plug-in for the jQuery JavaScript library enabling the creation of advanced HTML tables (Figure 3). In REDIportal, DataTables is used server-side through specific Ajax requests in order to handle and display tables consisting of millions of rows with ease.

For each RNA editing site, REDIportal tables provide different info such as: (i) a link to UCSC genome browser; (ii) the genomic position; (iii) the reference and edited nucleotide; (iv) the strand; (v) the dbSNP accession (if any); (vi) the editing location; (vii) the repeated element (if any); (viii) the gene symbol according to Gencode v19; (ix) the genic region; (x) the number of edited samples; (xi) the potential amino acid change; (xii) the PhastCons conservation score across 46 organisms; and (xi) a flag indicating in which database (ATLAS, RADAR or DARNED) is reported (Figure 3). Some table cells are colored and interactive with hyperlinks to external resources (Figure 3).

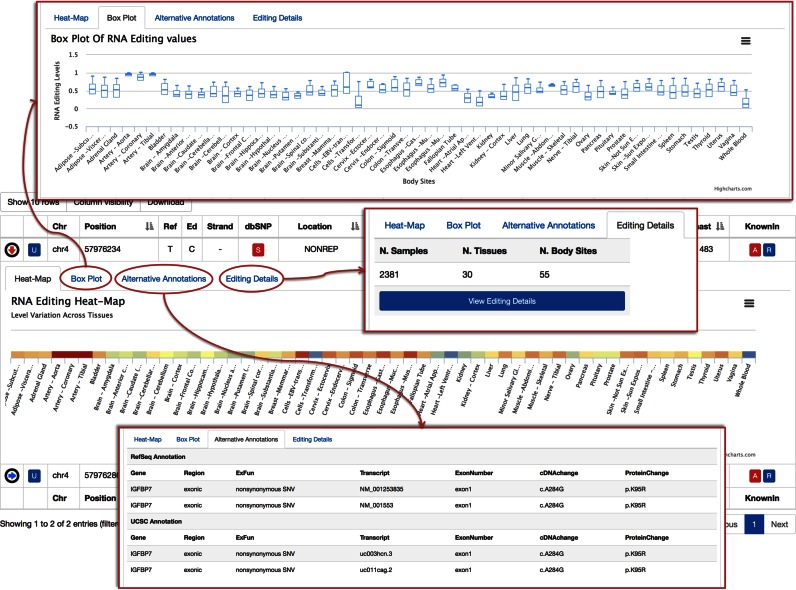

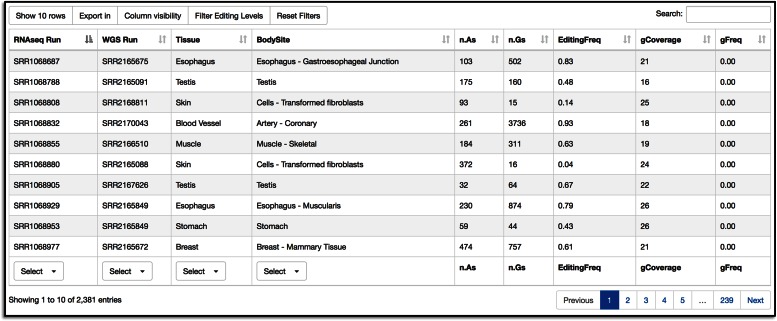

All rows of REDIportal tables comprise child rows containing extra information (Figure 4). Each child row consists of four panels: (i) an interactive heat map to explore RNA editing levels across body sites; (ii) an interactive box plot to look at editing level variation per body site; (iii) alternative gene/transcript annotations according to RefSeq and UCSC databases and (iv) editing details with the number of edited samples/tissues/body sites and a link to a further table containing RNA editing levels and the exact number of RNAseq and WGS reads supporting each event (Figures 4 and 5). This table can be sorted or filtered according to different criteria as the tissue of origin, the specific individual, the editing frequency or the number of read supporting the reference or edited nucleotide (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Extra information triggered on demand. Users can access detailed information on demand triggering the content in child rows. As shown in figure, each child row comprises four panels, indicated by red arrows and highlighted in red rectangles, and consists of: (i) an interactive heat map to explore RNA editing levels across body sites; (ii) an interactive box plot to look at editing level variation per body site; (iii) alternative gene/transcript annotations according to RefSeq and UCSC databases and (iv) editing details with the number of edited samples/tissues/body sites and a link to a further table containing RNA editing levels and the exact number of RNAseq and WGS reads supporting each event.

Figure 5.

RNA editing details. For each editing position, users can request detailed information displayed in dynamic and filterable tables. Such tables include valuable biological evidence such as the tissue or body site of origin, the number of edited or unedited reads, the WGS support and the detected editing levels.

Main REDIportal tables are downloadable in the tab-delimited text format after selecting relevant fields, while tables with RNA editing details are exportable in PDF or Excel formats. All tables support pagination and column visibility for a custom control of columns to display.

REDIportal is equipped with a detailed help page describing the main instructions to search and browse RNA editing sites.

JBrowse GENOME BROWSER

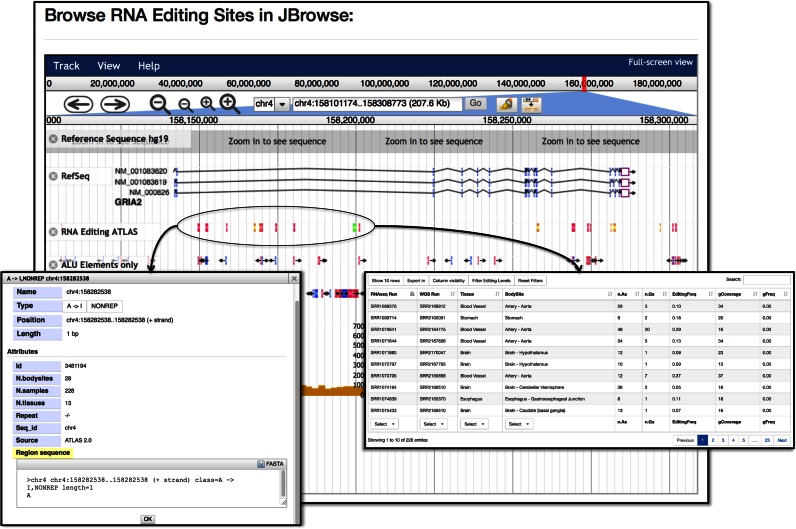

A primary mission of REDIportal is to centralize and integrate RNA editing annotations with existing biological and genomic data sets. This is mainly realized through interactive graphical displays and embedding an own genome browser. In contrast with previous editing databases, REDIportal deploys the powerful client-side and JavaScript-based JBrowse browser (18).

Through JBrowse, REDIportal users can explore RNA editing events in their genomic context and select diverse tracks including gene annotations from various repositories or repetitive elements in which RNA editing is prominent (Figure 6). A-to-I changes are shown in three different colors, red, green and orange, corresponding to the three main editing categories, ALU, REP and NONREP, respectively. Users can retrieve detailed RNA editing information by clicking on individual features (Figure 6). Left click triggers a pop-up window with genomic data, while right click causes the opening of a new window with info about editing levels, tissues and body sites, and supporting RNAseq and WGS reads (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

JBrowse in REDIportal. RNA editing sites can be easily inspected in their genomic context though JBrowse. Left click triggers a pop-up window with genomic data. Right click opens a new window with editing levels, tissues and body sites, and supporting RNAseq and WGS reads.

JBrowse is quite flexible and users may upload custom tracks to improve their genomic visualizations.

DISCUSSION AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENT

RNA editing is emerging as a relevant molecular mechanism to fine tune gene expression in humans. Thanks to large-scale investigations based on high-throughput RNA sequencing, we know that RNA editing is more pervasive than previously thought, with millions of RNA adenosines enzymatically modified in inosines by ADAR proteins. Although this huge amount of A-to-I changes, the exact biological role of RNA editing in humans has not been completely elucidated. To better understand such fascinating co-/post-transcriptional phenomenon, we have developed REDIportal, a specialized repository for A-to-I changes occurring in a variety of human tissues. Differently to available RNA editing databases such as RADAR and DARNED, REDIportal has been conceived to investigate the dynamic regulation of editing sites, enabling the inspection of A-to-I levels across 55 human body sites grouped in 30 tissues. REDIportal annotates more than 4.5 million events detected in 2660 RNAseq experiments from GTEx project and provides search results in sortable and downloadable tables for downstream analyses. In addition, our repository embeds a specific genome browser to explore RNA editing events in their genomic context.

Our ambition is to stimulate the scientific community in contributing to unravel the molecular and functional impact of RNA editing in humans. With this aim in mind, we have appropriately developed REDIportal to be a reference resource for RNA editing investigations.

Our short-term goal will be to include further RNA editing events from addition RNAseq data. We are actually completing computational analyses on more than 6,000 RNAseq experiments from GTEx project and we hope to incorporate in REDIportal RNA editing events deduced in RNAseq data from diseased samples, as those from TCGA atlas or those available in the public SRA database.

We are also planning to enrich REDIportal with additional features such as hyper-edited regions and Alu editing index that may significantly facilitate the comparison of RNA editing profiles across human tissues.

Finally, REDIportal will be extended to other organisms enabling comparative genomics investigations and will incorporate RNA editing changes from single cells for an increased resolution of this phenomenon.

AVAILABILITY

REDIportal and its facilities are freely available at http://srv00.recas.ba.infn.it/atlas/index.html. RNA editing tables are downloadable and usable without any restriction.

Acknowledgments

We kindly thank the ReCaS computing center at University of Bari, G. Donvito (National Institute of Nuclear Physics) and R. Valentini for computational and technical assistance. We also acknowledge the Jantsch Lab in Vienna and Levanon Lab in Tel Aviv for fruitful comments and suggestions on early versions of database. A special thank is addressed to Li Lab at Stanford for allowing the merging of RADAR annotations in REDIportal. We also acknowledge the European Elixir infrastructure (https://www.elixir-europe.org/) for supporting the development and maintenance of REDIportal.

The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) Project was supported by the Common Fund of the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health (commonfund.nih.gov/GTEx). Additional funds were provided by the NCI, NHGRI, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, and NINDS. Donors were enrolled at Biospecimen Source Sites funded by NCI\SAIC-Frederick, Inc. (SAIC-F) subcontracts to the National Disease Research Interchange (10XS170), Roswell Park Cancer Institute (10XS171), and Science Care, Inc. (X10S172). The Laboratory, Data Analysis, and Coordinating Center (LDACC) was funded through a contract (HHSN268201000029C) to The Broad Institute, Inc. Biorepository operations were funded through an SAIC-F subcontract to Van Andel Research Institute (10ST1035). Additional data repository and project management were provided by SAIC-F (HHSN261200800001E). The Brain Bank was supported by a supplement to University of Miami grant DA006227. Statistical Methods development grants were made to the University of Geneva (MH090941), the University of Chicago (MH090951 & MH09037), the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill (MH090936) and to Harvard University (MH090948). The datasets used for the analyses described in this manuscript were obtained from dbGaP through the accession number phs000424.v6.p1.

FUNDING

Italian Ministero dell'Istruzione, Università e Ricerca (MIUR) [PRIN 2012]; Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche: Flagship Project Epigen, Medicina Personalizzata, Aging Program, Interomics and Elixir-ITA. Funding for open access charge: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche: Flagship Project Epigen.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gott J.M., Emeson R.B. Functions and mechanisms of RNA editing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2000;34:499–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hogg M., Paro S., Keegan L.P., O'Connell M.A. RNA editing by mammalian ADARs. Adv. Genet. 2011;73:87–120. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380860-8.00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maas S., Kawahara Y., Tamburro K.M., Nishikura K. A-to-I RNA Editing and Human Disease. RNA Biol. 2014;3:1–9. doi: 10.4161/rna.3.1.2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallo A., Locatelli F. ADARs: allies or enemies? The importance of A-to-I RNA editing in human disease: from cancer to HIV-1. Biol. Rev. Cambr. Philos. Soc. 2012;87:95–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2011.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L., Li Y., Lin C.H., Chan T.H., Chow R.K., Song Y., Liu M., Yuan Y.F., Fu L., Kong K.L., et al. Recoding RNA editing of AZIN1 predisposes to hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Med. 2013;19:209–216. doi: 10.1038/nm.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picardi E., Manzari C., Mastropasqua F., Aiello I., D'Erchia A.M., Pesole G. Profiling RNA editing in human tissues: towards the inosinome Atlas. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:14941. doi: 10.1038/srep14941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maas S. Gene regulation through RNA editing. Discov. Med. 2011;10:379–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hood J.L., Emeson R.B. Editing of neurotransmitter receptor and ion channel RNAs in the nervous system. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2011;353:61–90. doi: 10.1007/82_2011_157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramaswami G., Lin W., Piskol R., Tan M.H., Davis C., Li J.B. Accurate identification of human Alu and non-Alu RNA editing sites. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:579–581. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiran A.M., O'Mahony J.J., Sanjeev K., Baranov P.V. Darned in 2013: inclusion of model organisms and linking with Wikipedia. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D258–D261. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramaswami G., Li J.B. RADAR: a rigorously annotated database of A-to-I RNA editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D109–D113. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Picardi E., Regina T.M., Verbitskiy D., Brennicke A., Quagliariello C. REDIdb: an upgraded bioinformatics resource for organellar RNA editing sites. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:360–365. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Picardi E., Regina T.M., Brennicke A., Quagliariello C. REDIdb: the RNA editing database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D173–D177. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Picardi E., Pesole G. REDItools: high-throughput RNA editing detection made easy. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1813–1814. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porath H.T., Carmi S., Levanon E.Y. A genome-wide map of hyper-edited RNA reveals numerous new sites. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4726. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang K., Li M., Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buels R., Yao E., Diesh C.M., Hayes R.D., Munoz-Torres M., Helt G., Goodstein D.M., Elsik C.G., Lewis S.E., Stein L., et al. JBrowse: a dynamic web platform for genome visualization and analysis. Genome Biol. 2016;17:66. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0924-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]