Abstract

The World Data Centre for Microorganisms (WDCM) was established 50 years ago as the data center of the World Federation for Culture Collections (WFCC)—Microbial Resource Center (MIRCEN). WDCM aims to provide integrated information services using big data technology for microbial resource centers and microbiologists all over the world. Here, we provide an overview of WDCM including all of its integrated services. Culture Collections Information Worldwide (CCINFO) provides metadata information on 708 culture collections from 72 countries and regions. Global Catalogue of Microorganism (GCM) gathers strain catalogue information and provides a data retrieval, analysis, and visualization system of microbial resources. Currently, GCM includes >368 000 strains from 103 culture collections in 43 countries and regions. Analyzer of Bioresource Citation (ABC) is a data mining tool extracting strain related publications, patents, nucleotide sequences and genome information from public data sources to form a knowledge base. Reference Strain Catalogue (RSC) maintains a database of strains listed in International Standards Organization (ISO) and other international or regional standards. RSC allocates a unique identifier to strains recommended for use in diagnosis and quality control, and hence serves as a valuable cross-platform reference. WDCM provides free access to all these services at www.wdcm.org.

INTRODUCTION

Microbial resources are essential to understand and develop life sciences because microorganisms are crucial to maintain the external environment as well as the inner ecosystem of humans, higher animals and plants. They are fundamental materials for scientific studies and used as reference materials and model organisms as well. Culture collections play a crucial role in long-term and stable preservation of these microbes, and provide authentic reference materials for scientists and industries. It was recommended by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Biological Resource Centre (BRC) Initiative that culture collections should evolve toward higher standards for Biological Resource Centres (www.oecd.org/sti/biotechnology/brc) focusing more on taxonomic and functional characteristics of microorganisms to provide comprehensive information to the users (1). Culture collections have a long history of scientific research collaborations, a very visible one is the genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea (GEBA) involving the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH (DSMZ) and the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE JGI) (2).

The World Federation for Culture Collections (WFCC) is a COMCOF (Committees, Commissions and Federations) of the International Union of Microbiological Societies (IUMS) and a scientific member of the International Union of Biological Sciences (IUBS). WFCC's major task is to promote and develop culture collections of microorganisms and cultured cells (3). As an active network, WFCC regularly organizes international conferences, distributes electronic newsletters and publications, to ensure the long term perpetuation of important microbial collections.

The World Data Center for Microorganisms (WDCM), launched in 1966, is the data center of WFCC and Microbial Resources Centers network (MIRCEN). WDCM is the global registry for culture collections and serves as an information resource for the user community.

In the 50-year history of WDCM, especially since the development of high-throughput sequencing technology, sequence data have increased exponentially, and the capabilities and uses of information technologies have expanded greatly. Microbiology and biotechnology are becoming data sciences. Culture collections have a growing function as data and information repositories to serve academia, industry and the public. As a result, WDCM is now working on facilitating the application of cutting-edge information technology to improve the interoperability of microbial data, promote the access and use of data and information, and coordinate international cooperation between culture collections, scientists and other user communities. Curators and scientists from culture collections not only share data but also design and implement this data platform to meet the changing requirements of microbial community.

WDCM DATABASES

The first World Directory of Collections of Cultures of Microorganisms was published in 1972 and established the foundation of the CCINFO database (4). In 1998 and 2002, WDCM conducted worldwide surveys and updated the CCINFO databases accordingly (5). The latest version of World Directory of Culture Collections was published in 2014 online through the WDCM webpage. However, because culture collections must meet the needs of rapidly growing biodiversity and genomic data, WDCM needs to develop expanded services to fulfil the requirements of culture collections.

Feedback from a survey (carried out in Spring 2013) to curators and users of 60 culture collections within the European Culture Collections’ Organisation (ECCO) shows the urgent requirement for convenient data accessibility (6). It is recommended that culture collections link their data to phylogenetic, genomic and publication information using their strain catalogues as interconnected data sources (7). However, microbial data are distributed across many different resource holders in various formats making a comprehensive data platform necessary for a better understanding of biological knowledge from such growing heterogeneous data. Utilization of emerging information technology provides the possibility to form such an integrated data platform.

Although some culture collections have already developed advanced data platforms, a large number of collections lag behind in digitization, largely because of the lack of facilities and human resources. According to statistics presented by CCINFO, of 708 registered culture collections, only 60 have published online catalogues and 96 have their catalogue computerized.

Thus the majority of culture collections represent a ‘silent majority’. Obviously, there is great imbalance in the development of culture collections, and unfortunately those who have difficulty in sharing their catalogue information online, are normally located in countries with greatest or special biodiversity and hence can be crucial for scientific research.

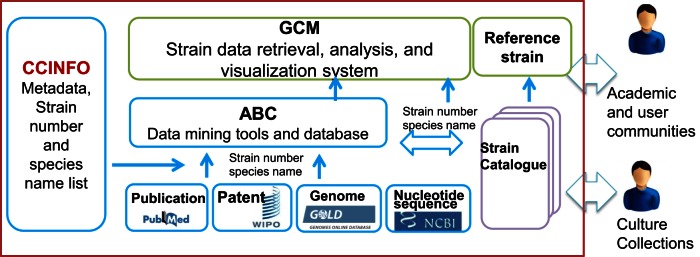

To provide an informative system to culture collections and users of microbial resources, WDCM constructed a comprehensive data platform and established several databases that are introduced below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A system-level overview of the WDCM databases.

CCINFO serves as a metadata recorder. It provides a unique identifier for each culture collection and lists the species names of collection's holdings. Using the strain numbers and species names, WDCM developed Analyzer of Bioresource Citation (ABC), a data mining tool to extract information from public resources such as Pubmed, WIPO, Genome Online database and NCBI nucleotide sequence database. After catalogue information is submitted from individual culture collection, WDCM automatically links this catalogue information with the available knowledge on each strain extracted by ABC, which is subsequently accessible to the public through the Global Catalogue of Microorganisms (GCM). The Reference strain database is a special subject database that provides information on the strains used in certain international or regional standards.

Culture collections information worldwide

Culture Collections Information Worldwide (CCINFO) is a registration system and metadata archive for culture collections around the world. WFCC recommends that every culture collection registers in the CCINFO database before providing public services. After receiving an application form, WDCM will assign a unique identification number to the collection. Since the first WDCM number ‘WDCM1’ was assigned to ATCC in 1981, WDCM has included 1130 unique identifiers. Besides the WDCM number, the application form also includes information about the acronym of the culture collection, which is normally the abbreviation of the culture collection name, for example, ‘ATCC’ for ‘American Type Culture Collection’ and ‘JCM’ for ‘Japan Collection of Microorganisms’. The WDCM administrator should ensure the acronym is unique because the acronym together with a systematic number assigned to the strains preserved in culture collection provides the unique identifier for each strain held, ‘ATCC 6051’ and ‘JCM 1002’ for example. A unique strain number is crucial to identify the strain globally, track its use and mine the utilization of the strain across various data resources. Currently there are a few occurrences of the duplication of strain numbers for historical reasons.

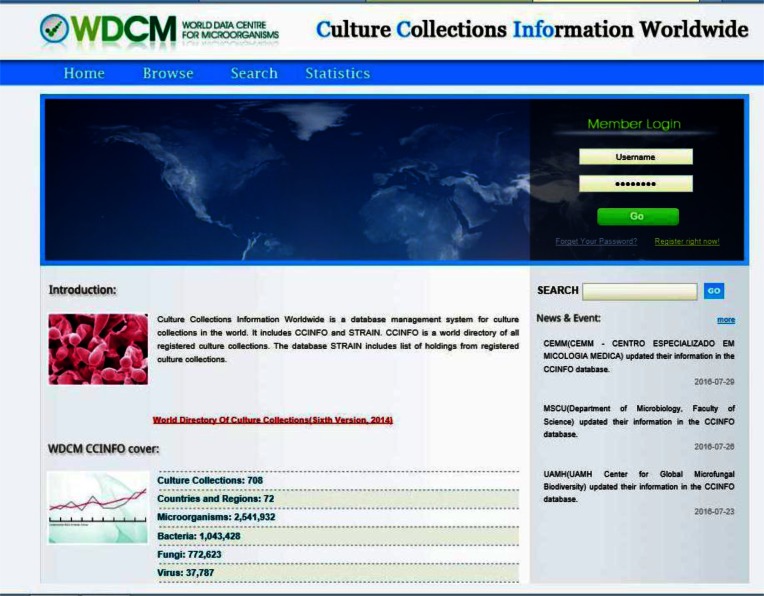

As a metadata archive, CCINFO stores detailed information about the funding, personnel, holdings and services of culture collections and includes information about 708 culture collections in 72 countries and regions up to July 2016. CCINFO provides users with an interface to search the database using keywords or a combination of several fields. A statistic summary of the core data is displayed online that is updated automatically (Figure 2). CCINFO also displays the geographical distribution of culture collection's location integrated with the Google Earth™ mapping service.

Figure 2.

Web interface of CCINFO database.

Analyzer of Bioresource citation

Data and knowledge generated from scientific research and utilization of microbial resources have historically been stored in different isolated databases. To solve the problem of identifying and accessing information on diverse platforms, WDCM developed a data mining tool called Analyzer of Bioresource Citation (ABC). The aim of ABC is to extract microbial resource related data and knowledge efficiently and precisely from the scientific literature, patents, and bioinformatics data and then integrate these data to form a readily accessible data warehouse.

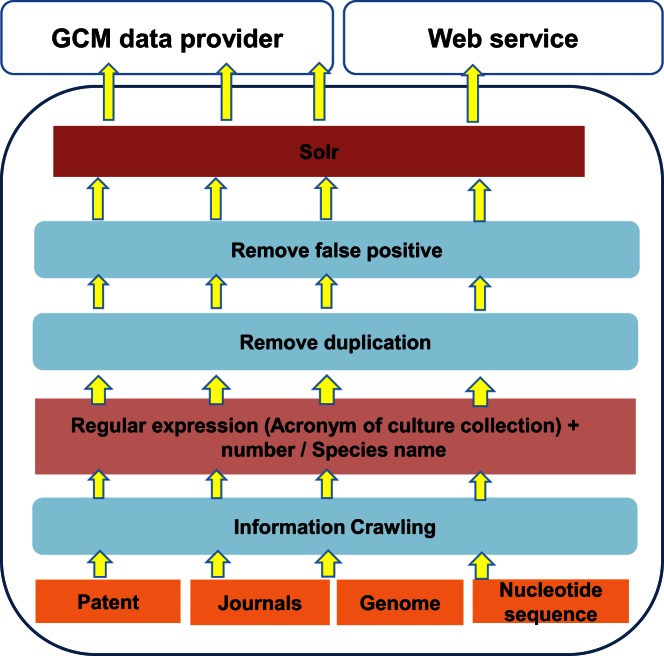

The ABC software works by selecting all the unique acronyms of culture collections registered in CCINFO and the list of species names preserved in these collections. The acronym list and species names list are used as keywords to search against data sources of publications, patents, genomes and nucleotide sequences. Regular expressions are used to make sure that data would not be missed. Data mining results are merged to form a data warehouse. After a clean database is established, the data are further linked to each specific strain using the collection-specific strain number (Figure 3). ABC provides services from both its own web service and also through GCM portal.

Figure 3.

ABC data mining working flow.

To date, the ABC tool has been used to mine data on strains from 131 culture collections registered with CCINFO. This has resulted in linking strains to more than 137 983 literature articles, more than 36 729 patents, 2473 genomes and greater than 348 047 nucleotide sequence entries (Table 1). The precision of the data was calculated; for the full dataset of 137 983 papers mined from public data resources, we randomly chose a dataset of 400 papers, after a manual data check, it was found that 86 of 400 were false positive results. The precision is therefore 78.5% with 95% confidence intervals.

Table 1. Statistical summary of the results from the ABC tool.

| Data Type | Resources Identified | Isolates included |

|---|---|---|

| Papers | 137 983 Papers | 73 817 strains |

| Patents | 36 729 Patents | 38 457 strains |

| Genomes | 2473 Genomes | 1920 strains |

| Nucleotide | 348 047 Nucleotide | 73 617 strains |

Global catalogue of microorganisms

To help culture collections to establish an online catalogue and provide users a system with fast, accurate and convenient data accessibility, WDCM launched the Global Catalogue of Microorganisms (GCM) project in 2012. The project started with several volunteer culture collections in its pilot stage; now the current version of GCM contains information on 368 982 strains, which includes 46 600 bacterial, fungal and archaea species from 103 collections in 43 countries and regions. Among the 103 culture collections, only one third of them have established an independent online catalogue. However, for those culture collections that cannot make their data available online, the GCM project succeeded in presenting their catalogues. As such, GCM has become one of the largest international cooperation projects in the field of microbial resources, greatly fostering accessibility to microbial resources and therefore their utilization worldwide.

To generate this resource, strain catalogue information was submitted in electronic form from culture collections. Before being published on the GCM webpage, the system performs automatic data quality control including validation of the data format and contents, and phylogenetic status of species names. GCM contains not only the catalogue information from culture collections, but also knowledge on strains and species extracted from the public databases, due to its connection with ABC data mining results.

The online system provides multiple searching functions. Besides the basic search of species name and strain number, the advanced search may combine multiple data fields such as marker gene sequence similarity and keywords in publications or patents. This greatly facilitates the exploration of the GCM content and provides the possibility to answer questions that require integration of data from different data resources. Details of the GCM database were described in a previous publication (8).

Reference strain database

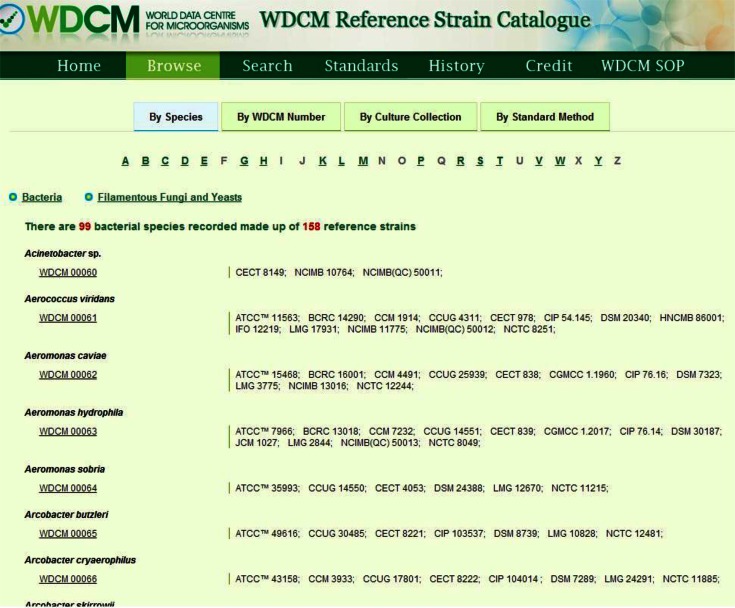

Reference strains are used in testing of products, as positive and negative controls, as indicator organisms, or as identification standards. The WDCM Reference Strain Catalogue (RSC) was defined by the ISO TC 34 SC 9 Joint Working Group 5 and by the Working Party on Culture Media of the International Committee on Food Microbiology and Hygiene (ICFMH-WPCM) in their published Handbook of Culture Media for Food and Water Microbiology (9). RSC thus provides a unique system of identifiers for strains. The 27th version of ‘Reference strain catalogue pertaining to organisms for performance testing culture media’ was published online (http://refs.wdcm.org/pdf/WDCM%20Catalogue%20Version_V27.1.pdf). The database lists 194 strains of 126 species from 47 culture collections, and covers 65 international and national standards, 20 of which are ISO standards.

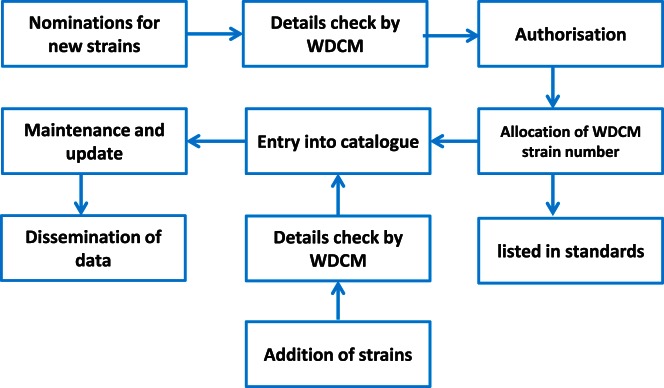

Bacterial or fungal strains suitable for inclusion in the WDCM reference strain database must have been deposited in at least two collections with Affiliate status with the WFCC. Nominations for new strains will only be received from ISO, member bodies of ISO or constituent bodies of the International Union of Microbiological Societies. After receiving the nomination for new strains, WDCM staff check the details and if it is approved, a unique WDCM strain number is allocated to the strain (Figure 4). Multiple strain numbers for a single line of test strain are not accepted from any single collection under each WDCM identifier.

Figure 4.

Workflow of RSC processing.

Any WFCC Affiliate Collection member may nominate strains from their collection that are proven to be equivalent to strains already existing in the WDCM reference strain database for inclusion in the reference strain catalogue. It is the responsibility of the Affiliate Collection members to ensure that the characteristics of the proposed strain from their collection agree with those of the strains already listed. Validation must be provided that the nominated additional strain is a line of the original strain selected for the specific standard/test. The reference strain database provides a convenient access point to the catalogue and is searchable by species, WDCM number, culture collection and standard name (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Browse page of strain information.

Data integration method

The outside data sources complied in the WDCM database include:

Catalogue Information provided by individual culture collection or regional networks of culture collections.

Data from public data sources such as the US National Library of Medicine (PubMed) (10), World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO, http://www.wipo.int/portal/en/index.html) and national patents administrations, the NCBI genome project database (11) and the NCBI nucleotide sequence database (12).

Links to other external databases, such as RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) (13) and UniProt (14).

Data standards are used to ensure uniform formats

The current situation is that culture collections’ catalogues are in various data formats. Different collections have different data fields. They may have a different field name even for the same biological contents. Therefore, it is crucial to have a data standard to integrate the catalogue information. After a comprehensive comparison of existing data standards and the online catalogue, GCM developed the WDCM minimum datasets (MDS) and recommended datasets (RDS) based on widely applied standards such as the OECD Best Practice Guidelines for Biological Resource Centres (15), the Microbial Information Network Europe (MINE) (16), WFCC recommended data standards, as well as the Common Access to Biological Resources and Information (CABRI) (http://www.cabri.org/). A detailed description, together with examples of 15 WDCM MDS items can be found at (http://gcm.wfcc.info/datastandards/).

A unique strain number based data mining

As described above, the acronym of culture collection plus a unique systematic number are used to identify each strain, for example, ‘JCM 1002’ JCM is the acronym of Japan Collection of Microorganisms and 1002 is the systematic number this collection assigned to the strain. When the strain is further studied or utilized in a publication or patent, the strain number is cited in the text. The ABC data mining tool therefore can track strains through publications and public online databases whilst also accessing the strain related information using the unique strain number.

Species browse by phylogenetic tree

In the data warehouse, strains belonging to the same species as well as sub-species are automatically bound to a species level in a phylogenetic tree. The Catalogue of Life (http://www.catalogueoflife.org/) taxonomy tree is used to organize microorganisms and strain information. Because of this built-in structure, users can browse or search by species name or strain number on the tree.

SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

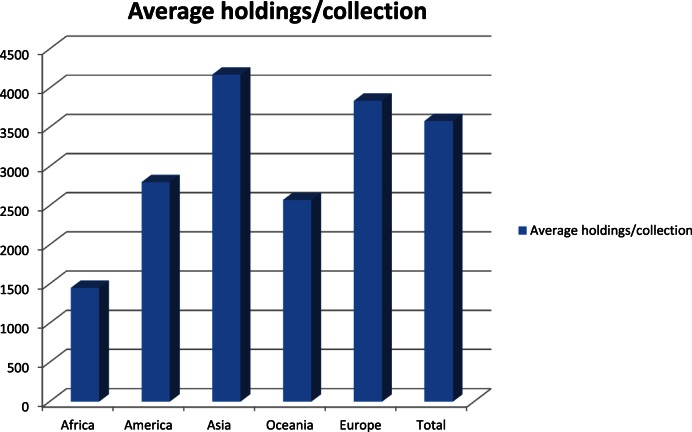

Possibilities exist to find or integrate all publicly available strains and their associated data. We demonstrate here how beneficial this can be. To date 103 of the 708 collections registered at WDCM have provided their strain data. With the WDCM Knowledge Bank from the incorporation of 2.5 million strains of the 708 registered collections, the benefits will be enormous. Table 2 and Figure 6 shows the distribution of these collections, noting that a large proportion of these collections are currently ‘hidden’, i.e. without online data of their strains. These ‘hidden’ strains could have interesting properties with potential for new drugs or industrial products.

Table 2. Statistic summary of culture collection distribution.

| Continents | Number of countries | Number of collections | Number of holdings | Average holdings/collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 7 | 11 | 15 935 | 1448 |

| America | 11 | 178 | 497 894 | 2797 |

| Asia | 17 | 246 | 1 025 865 | 4170 |

| Europe | 33 | 232 | 889 837 | 3835 |

| Oceania | 4 | 41 | 105 379 | 2570 |

| Total | 72 | 708 | 2 534 910 | 3580 |

Figure 6.

Average holdings per collection by different continents.

There are many reasons why tracking strains is important, the WDCM provides this opportunity with its integrated services. For example, knowing the association of a specific strain with its relevant intellectual property (in publications or patents) will enable appropriate understanding of the potential of the strain. Another reason why tracking strains and their utilisation is useful is in meeting benefit sharing requirements since the ‘Nagoya protocol on access to genetic resources and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from their utilization (Nagoya protocol)’ (https://www.cbd.int/abs/about/default.shtml) came into force.

Among the top 10 countries with the largest number of holdings (Table 3), there is an imbalance among countries. The United States and Japan are the strongest in microbial resources preservation and utilization. Some developed countries such as Denmark and Belgium have a long history and provide a great foundation for microbial research, although the total number of holdings is not so large. Microbial resources are maintained by fewer centers holding larger numbers of strains. This suggests a clear focus on centralized public service collections rather than a distributed network of smaller research based collections. In contrast, Brazil and Thailand, countries with high biodiversity, have the largest number of collections but the smallest average number of strains per collection. This probably suggests specialization based on the disciplines the collection serves, regional characteristics or research focus.

Table 3. Top 10 countries with the largest number of holdings.

| Rank | Countries and regions | Total holdings | Number of collections | Average holdings/collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USA | 261 637 | 29 | 9022 |

| 2 | Japan | 254 830 | 26 | 9801 |

| 3 | India | 194 174 | 30 | 6472 |

| 4 | China | 182 235 | 19 | 9591 |

| 5 | Republic of Korea | 167 090 | 23 | 7264 |

| 6 | Brazil | 114 494 | 77 | 1483 |

| 7 | Denmark | 102 066 | 3 | 34 022 |

| 8 | Thailand | 99 323 | 63 | 1577 |

| 9 | Germany | 95 593 | 13 | 7353 |

| 10 | Belgium | 93 421 | 7 | 13 346 |

ABC provides a useful analytical tool to find which species are being used as research tools. Table 4 shows the highest cited genera in publications. Among these genera, a large number are related with disease infection, such as rickettsia, Streptococcus and Salmonella. Saccharomyces is the fourth most common species and widely used in fermentation and ethanol industries, and also as a model organism for research on cell biology, population and evolutionary genetics. Other species such as Pseudomonas and Sclerotinia are relevant to plant diseases.

Table 4. Top 10 highest cited genus in ABC database.

| Genus | Paper counts |

|---|---|

| Rickettsia | 173 189 |

| Staphylococcus | 95 829 |

| Saccharomyces | 71 001 |

| Pseudomonas | 64 904 |

| Mycobacterium | 63 261 |

| Streptococcus | 55 547 |

| Sclerotinia | 41 428 |

| Salmonella | 36 043 |

| Helicobacter | 29 060 |

| Clostridium | 25 759 |

Impact

Scientists or industries can access a wealth of research data through WDCM services. It is possible to target the breadth of organisms held by the WDCM public service collections on the basis of their properties, to access the research carried out on specific organisms and as a result to better understand the potential of the organisms of concern. Biological resource centers around the world are among the most influential institutions and support diverse research and economic development activities. Patent and biodiversity collections have provided resources for human health, such as antibiotic, immunosuppressive and pharmaceutical producing strains, for plant health such as biocontrol strains, and for industry including citric acid, pigment, vitamin, and food and fiber processing. Culture collections have served as the foundation for projects leading to the discovery of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as well as diverse restriction enzymes and other enzymes underlying the recombinant DNA technology revolution. The ability to track citations to the use of the strains in these collections shows high impact, through direct citation, and also to citations to research using these materials.

Future directions

The WDCM database is now using a centralized model for data integration. Future developments such as ‘BIG DATA’ technology including semantic web or linked data will allow the system to provide more flexible data integration with broader data sources. Linking WDCM strain data to broader data sets such as environmental, chemistry and research literature can add value to data mining and targeting microorganisms as potential sources of new drugs or industrial products. Linking microbial strain data to climate information, agricultural and environmental data can provide tools for climate-smart agriculture and food security. WDCM will work with Research Infrastructures, Publishers, Research funders, Data holders and individual collections and scientists to ensure data interoperability and the provision of enhanced tools for research and development.

Cooperation with other organizations and institutions will promote broad utilization of the WDCM data platform. WDCM is exploring collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) to establish a database allowing influenza virus information integration. Moreover, the WDCM database provides services to allow culture collections to comply with the Convention on Biological Diversity and Nagoya protocol for Access and Benefit Sharing. The unique strain identifier available at WDCM together with the information extracted by ABC implements key provisions of the Nagoya Protocol and provides required transparency, legal certainty while lowering transaction costs and reducing administrative and governance burdens. The new demands from the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations to collect data on soil microorganisms to monitoring systems for biodiversity for food and agriculture, concomitant with climate change challenges, show the necessity of managing big data in this field. WDCM is driven towards continuous development to meet increasing demands worldwide.

Acknowledgments

WDCM thanks the supports by WFCC Executive board. WDCM acknowledges the contributions of all participating collections to the GCM project. At the time of writing this article 103 collections from 43 countries have already joined the effort.

FUNDING

National High Technology Research and Development Program of China [2014AA021501, 2014AA021503, 2015AA020108]; International S&T Cooperation Program of China (ISTCP) [2015DFG32550]; Bureau of Science & Technology for Development of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Strategic bio-resources information center) and Field Cloud Project of Chinese Academy of Sciences [XXH12503-05-01]. Funding for open access charge: National High Technology Research and Development Program of China [2014AA021501, 2014AA021503, 2015AA020108]; International S&T Cooperation Program of China (ISTCP) [2015DFG32550] ; Bureau of Science & Technology for Development of Chinese Academy of Sciences [Strategic bio-resources information center]; Field Cloud Project of Chinese Academy of Sciences [XXH12503-05-01].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.David S. Culture collections over the world. Int. Microbiol. 2003;6:95–100. doi: 10.1007/s10123-003-0114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dongying W., Philip H., Konstantinos M., Rüdiger P., Eileen D., Natalia N.I., Victor K., Lynne G., Martin W., Brian J.T., et al. A phylogeny-driven genomic encyclopaedia of Bacteria and Archaea. Nature. 2009;462:1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature08656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WFCC Executive Board. World Federation for Culture Collections Guidelines. 3rd edn. 2010. http://www.wfcc.info/guidelines/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skerman V.B.D. World Directory of Collections of Cultures of Microorganisms. NY: John Wiley Sons, Inc; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satoru M., Hideaki S. Networking of biological resource centres: WDCM experiences. Data Sci. J. 2002;1:229–234. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serge C., Alexander V., Paolo R., Vincent R., Svetlana O., Anna K., Frank O.G., David S. An information system for European culture collections: the way forward. SpringerPlus. 2016;5:772. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2450-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dilip K.A., Ratul S., Ram D., David S. Current status, strategy and future prospects of microbial resource collections. Curr. Sci. 2005;89:488–495. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linhuan W., Qinglan S., Hideaki S., Song Y., Yuguang Z., Kevin M., Alexander V., Suzuki k.I., Moriya O., Yeonhee L., et al. Global catalogue of microorganisms (GCM): a comprehensive database and information retrieval, analysis, and visualization system for microbial resources. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:933. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janet E.L.C., Gordon D.W.C., Rosamund M.B. Handbook of Culture Media for Food and Water Microbiology. 3rd edn. The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.NCBI Resource Coordinators. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D7–D19. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul A.K., Deanna M.C., Françoise T., Jinna C., Vichet H., Victor S., Robert G.S., Tatiana T., Charlie X., Andrey Z., et al. Assembly: a resource for assembled genomes at NCBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D73–D80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karen C., Ilene K.M., David J.L., James O., Eric W.S. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D67–D72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peter W.R., Andreas P., Chunxiao B., Wolfgang F.B., Cole H.C., Shuchismita D., Rachel K.G., David S.G., John D.W., Jesse W., et al. The RCSB Protein Data Bank: views of structural biology for basic and applied research and education. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;43:D345–D356. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics Members. The SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics’ resources: focus on curated databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D27–D37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.OECD. OECD Best Practice Guidelines for Biological Resource Centres. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gams W., Hennebert G., Stalpers J., Janssens D., Schipper M., Smith J., Yarrow D., Hawksworth D. Structuring strain data for storage and retrieval of information on fungiand yeasts in MINE, the Microbial Information Network Europe. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1988;134:1667–1689. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-6-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]