Accumulation of the transcription factor GOLDEN2-LIKE 1 in response to plastid signals is regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Abstract

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) GOLDEN2-LIKE (GLK) transcription factors promote chloroplast biogenesis by regulating the expression of photosynthesis-related genes. Arabidopsis GLK1 is also known to participate in retrograde signaling from chloroplasts to the nucleus. To elucidate the mechanism by which GLK1 is regulated in response to plastid signals, we biochemically characterized Arabidopsis GLK1 protein. Expression analysis of GLK1 protein indicated that GLK1 accumulates in aerial tissues. Both tissue-specific and Suc-dependent accumulation of GLK1 were regulated primarily at the transcriptional level. In contrast, norflurazon- or lincomycin-treated gun1-101 mutant expressing normal levels of GLK1 mRNA failed to accumulate GLK1 protein, suggesting that plastid signals directly regulate the accumulation of GLK1 protein in a GUN1-independent manner. Treatment of the glk1glk2 mutant expressing functional GFP-GLK1 with a proteasome inhibitor, MG-132, induced the accumulation of polyubiquitinated GFP-GLK1. Furthermore, the level of endogenous GLK1 in plants with damaged plastids was partially restored when those plants were treated with MG-132. Collectively, these data indicate that the ubiquitin-proteasome system participates in the degradation of Arabidopsis GLK1 in response to plastid signals.

Plant cells have evolved complex mechanisms to coordinate nuclear gene expression depending on the functional state of plastids. Nuclear-encoded plastid proteins are required for plastid biogenesis (Inaba and Schnell, 2008). Furthermore, light-absorbing plastids are subjected to oxidative stress, requiring plants to finely tune their cellular activities to adapt to environmental conditions (Szechyńska-Hebda and Karpiński, 2013). Thus, retrograde signals from plastids to the nucleus, referred to as plastid signals, have been proposed to play key roles in coordinating nuclear gene expression with the functional and metabolic states of plastids (Inaba et al., 2011; Chi et al., 2013; Jarvis and López-Juez, 2013).

Regulation of nuclear gene expression by plastids is divided into two mechanisms: biogenic and operational control (Pogson et al., 2008). Biogenic control is attributed to the regulation of genes necessary for the construction of the photosynthetic apparatus. This mechanism is critical for proper assembly of the photosynthetic apparatus and chloroplast biogenesis (Pogson et al., 2008; Inaba et al., 2011; Chi et al., 2013; Jarvis and López-Juez, 2013). In contrast, operational control enables plastids to regulate the expression of nuclear genes in response to environmental cues, enabling plants to optimize photosynthetic performance. To date, several molecules, including reactive oxygen species (Karpinski et al., 1999; Wagner et al., 2004), methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (Xiao et al., 2012), and 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-P (Estavillo et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2016), have been shown to participate in operational control.

Transcriptional activator GOLDEN2-LIKE (GLK) proteins play key roles in biogenic control of nuclear gene expression by plastid signals (Jarvis and López-Juez, 2013). The GLK genes positively regulate the expression of photosynthesis-related genes in numerous plants (Yasumura et al., 2005; Waters et al., 2009). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), there are two copies of GLK genes, designated as GLK1 and GLK2, which function redundantly to regulate chloroplast biogenesis. The glk1glk2 double mutant exhibits a pale-green phenotype (Fitter et al., 2002). Furthermore, overexpression of GLK has been shown to be sufficient to induce chloroplast development in rice calli (Nakamura et al., 2009) and Arabidopsis root cells (Kobayashi et al., 2012). When Arabidopsis plants are subjected to treatments that induce plastid signals, expression of GLK1 is suppressed (Kakizaki et al., 2009; Waters et al., 2009; Kakizaki et al., 2012). GLK genes appear to regulate chloroplast biogenesis positively and are involved in biogenic control; however, to date, the biochemical nature of GLK1 protein has not been characterized. Chimeric GLK genes fused to GFP and introduced into a glk1glk2 double mutant complemented a pale-green phenotype (Waters et al., 2008), but chimeric proteins have not been detected by fluorescence microscopy or immunoblotting. This may be likely because GLK proteins are highly unstable, or because the level of GLK proteins is strictly regulated in vivo.

Transcription factors involved in plastid-to-nucleus signaling are regulated by multiple mechanisms (Chi et al., 2013). As stated above, the expression of GLK1 has been shown to respond to treatments that induce plastid signals (Kakizaki et al., 2009). In contrast, posttranslational activation of another transcription factor, ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 4 (ABI4), prevents the binding of G-box binding factors to the light-harvesting chlorophyll a/b-binding protein (LHCB) promoter upon inhibition of plastid biogenesis, thereby suppressing expression of LHCB in the nucleus (Koussevitzky et al., 2007). The activation of ABI4 involves a plant homeodomain transcription factor with transmembrane domains (PTM), which localizes to the nucleus and chloroplasts. When plastids are subjected to stress, the N terminus of PTM is cleaved by proteolysis and moves into the nucleus, thereby activating transcription of ABI4 and allowing plant cells to suppress photosynthesis-related genes (Sun et al., 2011; Chi et al., 2013). Hence, regulation of transcription factors at both transcriptional and posttranslational levels is important in plastid-to-nucleus retrograde signaling.

In this study, we demonstrate that ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent posttranslational regulation plays a key role in the accumulation of GLK1 protein in response to plastid signals. We raised antibodies against GLK1 and successfully detected GLK1 protein. The level of GLK1 protein was decreased by treatments that induce plastid damage, regardless of the level of GLK1 mRNA. Furthermore, this decrease of GLK1 was attenuated by treatment with a proteasome inhibitor, MG-132. Our results show that plastid signals down-regulate the accumulation of GLK1 through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

RESULTS

Production of Specific Antibodies against GLK1 Protein

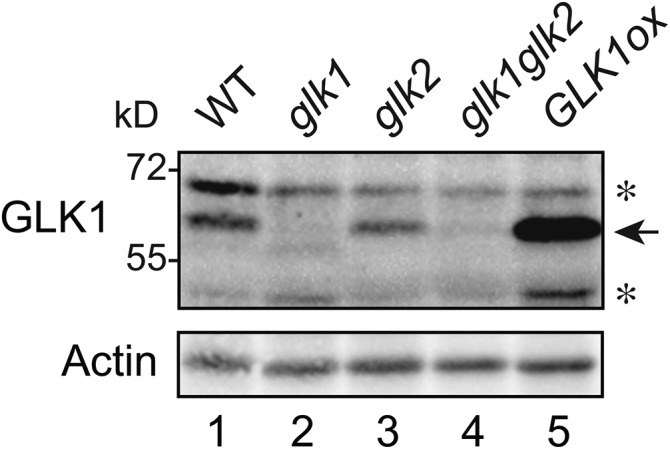

Both genetic and transgenic studies have demonstrated that GLK1 participates in the induction of photosynthesis-related genes and plastid-to-nucleus signaling (Kakizaki et al., 2009; Waters et al., 2009). However, to date, stable, high-yield purification of GLK1 has been unsuccessful and has prevented biochemical characterization of the protein. To investigate the mechanism by which GLK1 protein accumulation is regulated, we first purified NusA-TEV-GLK1-His fusion protein expressed in Escherichia coli (Supplemental Fig. S1) and raised antibodies against GLK1. As shown in Figure 1, we confirmed the specificity of our antibodies to GLK1 using glk1, glk2, and glk1glk2 mutants, and a GLK1ox line overexpressing GLK1 (Fig. 1). The antibodies detected an approximately 60-kD protein in wild-type, glk2, and GLK1ox plants (Fig. 1). The apparent molecular mass of this band was slightly higher than the predicted molecular mass of GLK1 (approximately 47 kD), and most abundant in GLK1ox plants (Fig. 1). Further, this band was not detected in either glk1 or glk1glk2 mutants. Hence, we concluded that the approximately 60-kD band is indeed GLK1 and that the antibodies we raised can detect endogenous GLK1.

Figure 1.

Detection of GLK1 protein by affinity purified anti-GLK1 antibodies. Total proteins were extracted from wild-type, glk1, glk2, glk1glk2, and GLK1 overexpressing (GLK1ox) Arabidopsis plants, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and probed with antibodies against GLK1. Asterisks indicate nonspecific proteins detected by antibodies.

Levels of GLK1 Protein Are Attributable to Tissue-Specific Expression of GLK1 Gene

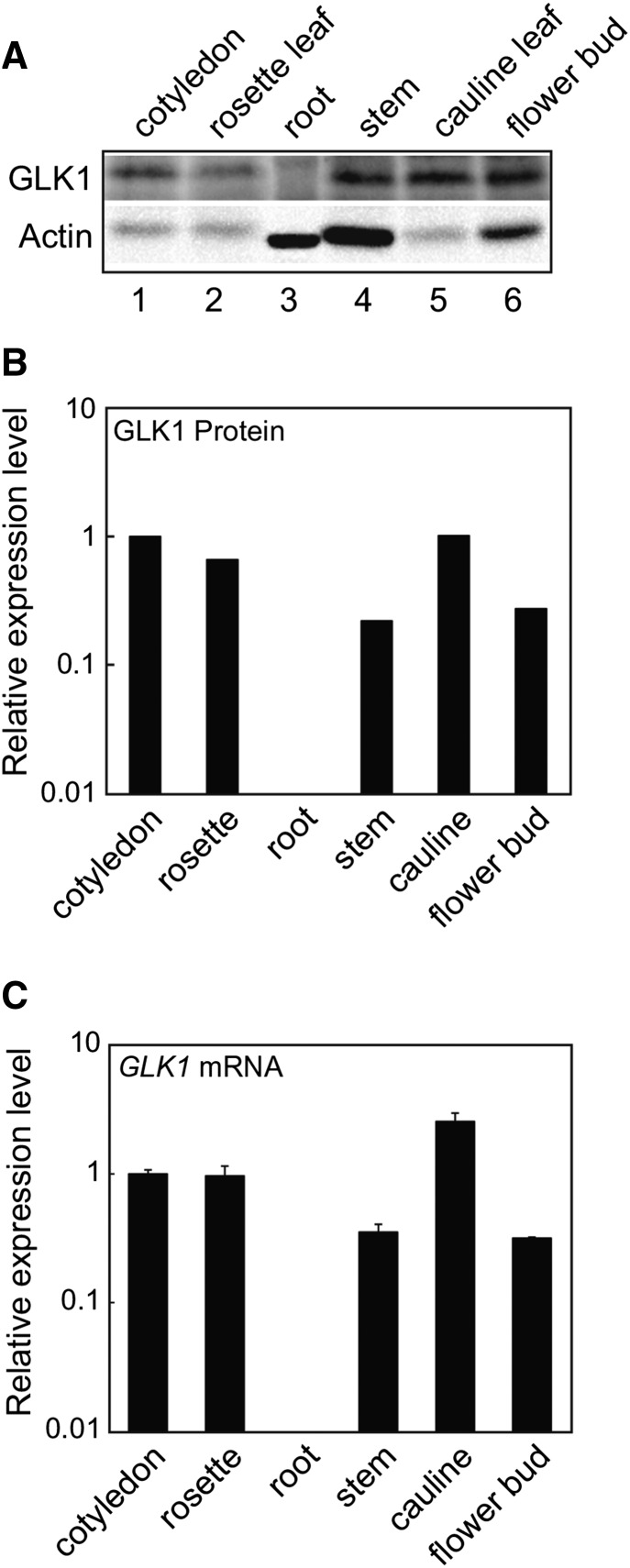

A previous study showed that GLK1 is expressed in aerial tissues but not in roots (Fitter et al., 2002). This finding is consistent with the fact that GLK1 participates in the coordinated expression of photosynthesis-related genes (Waters et al., 2009). To determine whether mRNA transcript levels are correlated with GLK1 protein accumulation, we examined tissue-specific accumulation of GLK1 using anti-GLK1 antibodies. As shown in Figure 2, GLK1 accumulates in aerial tissues but not in roots. When signal intensities of GLK1 were normalized to those of actin, it was apparent that GLK1 protein was most abundant in leaf tissue (Fig. 2B). This distribution of GLK1 is consistent with GLK1 mRNA accumulation (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that tissue-specific accumulation of GLK1 protein is primarily regulated at the transcriptional level.

Figure 2.

Tissue-specific accumulation of GLK1 protein in Arabidopsis. A, Accumulation of GLK1 protein in various tissues of Arabidopsis. Total protein was extracted from various tissues, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and probed with antibodies against GLK1 (upper panel) or actin (lower panel). The amount of protein loaded in each lane was as follows: 30 μg for root and 80 μg for other tissues. B, Quantification of GLK1 protein levels in each tissue. Protein levels were quantified using image acquisition software and normalized to actin levels. Each black bar represents the average of two independent samples. The GLK1 protein level in the cotyledon was set to 1. C, Quantitative analysis of GLK1 mRNA abundance in various tissues. Total RNA was extracted from various tissues of wild-type plants. The mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR, and the expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. The expression level in the cotyledon was set to 1. Error bars represent 1 se of the mean (n = 3).

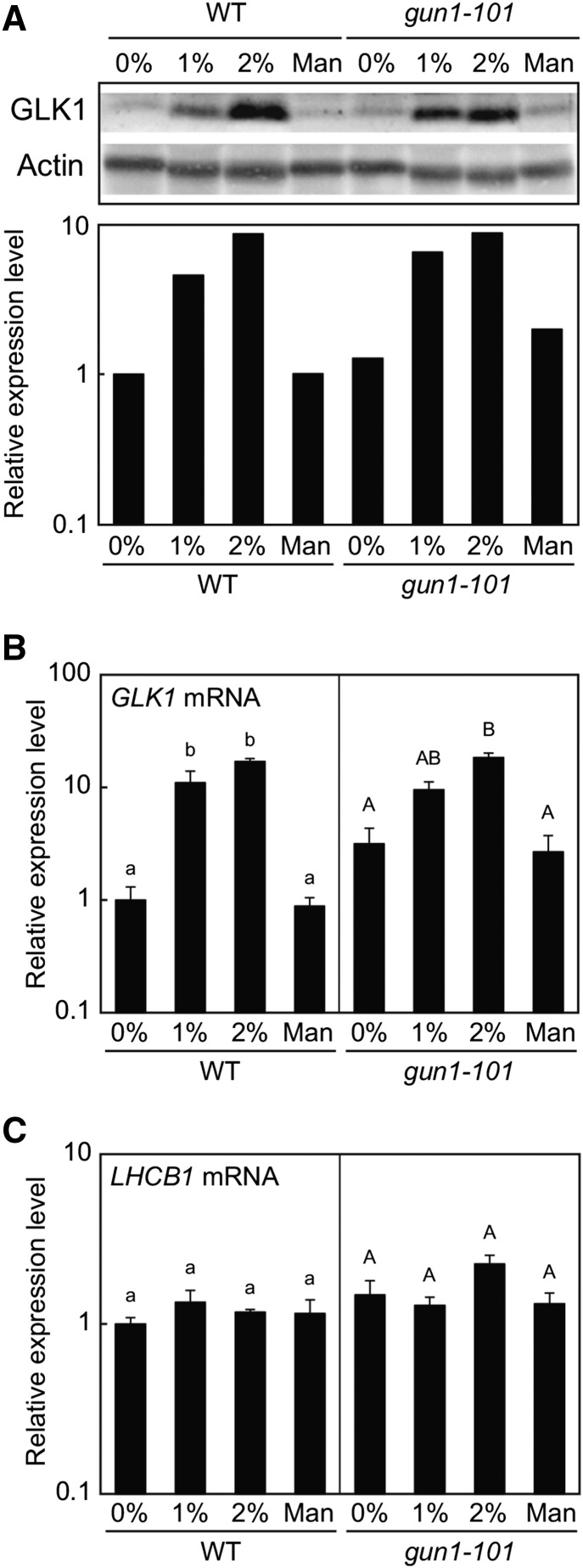

Suc Up-Regulates the Expression of GLK1 in a GUN1-Independent Manner

During the detection of GLK1 protein in each tissue, we noted that the level of GLK1 in rosette leaves was lower for plants grown in soil than on MS plates. Because we routinely supply Suc to MS plates, we suspected that Suc may up-regulate the expression of GLK1. Consistent with this idea, it has been shown that carbohydrate metabolism in chloroplasts affects the expression of GLK1 in the nucleus (Paparelli et al., 2012). Hence, we tested the effect of Suc on the accumulation of GLK1. We extracted crude proteins from wild-type plants grown on MS plates containing different concentrations of Suc. To control for osmotic pressure, we also included plants grown on mannitol. Wild-type plants accumulated only small amounts of GLK1 in the absence of Suc (Fig. 3). However, addition of Suc significantly increased the accumulation of GLK1 (Fig. 3A). This increase was dose dependent, as plants grown on 2% Suc accumulated more GLK1 protein. The accumulation of GLK1 protein was consistent with that of GLK1 mRNA (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the expression of LHCB1 did not respond to Suc dramatically in our experimental conditions (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that Suc regulates the expression of GLK1 mRNA, thereby affecting the accumulation of GLK1 protein.

Figure 3.

GLK1 accumulation in response to Suc. A, Immunoblot analysis of GLK1 protein in the wild-type and gun1-101 mutant plants treated with Suc (1% or 2%) or mannitol (1.06%, equivalent to 2% Suc in terms of molar concentration). Total protein was extracted from Suc- or mannitol-treated plants, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and probed with antibodies against GLK1 or actin (upper panel). The protein levels in each image were quantified using image acquisition software and normalized to actin levels (lower panel). The GLK1 protein level in untreated wild-type plants was set to 1. B and C, Quantitative analysis of GLK1 (B) and LHCB1 (C) expression in wild-type and gun1-101 mutant plants treated with Suc or mannitol. The mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR, and the expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. Error bars represent 1 se of the mean (n = 3). The expression level in untreated wild-type plants was set to 1. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between samples within each genotype by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test (P < 0.05). WT, wild type.

A previous study suggested that plastid-localized PPR protein, GUN1, participates in the Suc-dependent regulation of anthocyanin accumulation (Cottage et al., 2010). Furthermore, our previous study indicated that GUN1 regulates expression of GLK1 in the nucleus when plastids are damaged (Kakizaki et al., 2009). Therefore, we also tested if GUN1 regulates GLK1 expression in a Suc-dependent manner. Compared to the wild type, the gun1-101 mutant accumulated slightly higher levels of GLK1 in the absence of Suc (Fig. 3B). However, the gun1-101 mutation did not affect Suc-dependent induction of GLK1 expression (Fig. 3B). GLK1 transcript levels correlate with GLK1 protein levels in gun1-101 mutants (Fig. 3, A and B). These results suggest that Suc regulates the expression of GLK1 in a GUN1-independent manner.

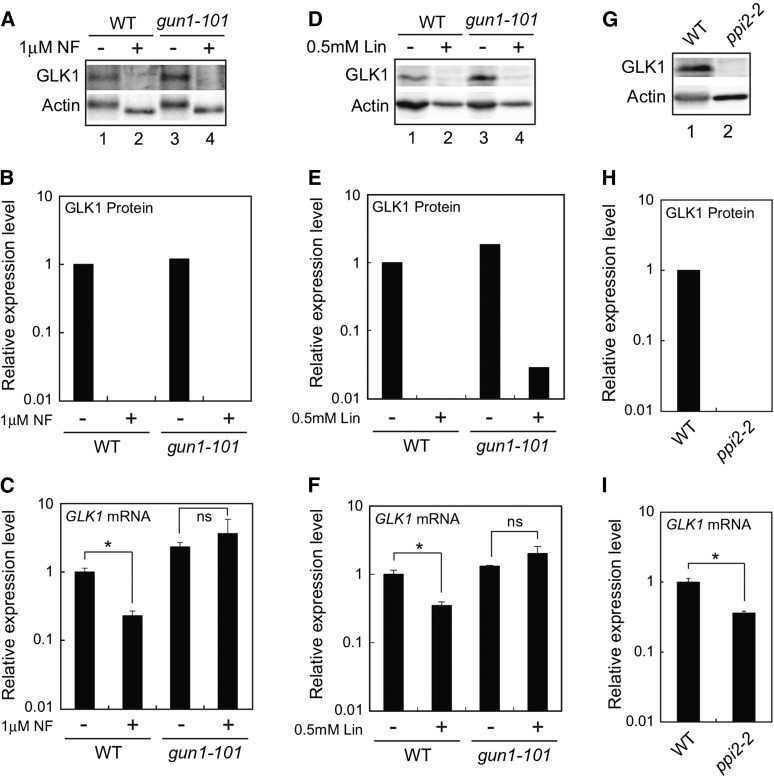

Damaged Plastids Directly Regulate the Accumulation of GLK1 in a GUN1-Independent Manner

We next investigated if plastid signals also regulate GLK1 protein accumulation at the posttranscriptional level. Previous studies demonstrated that expression of GLK1 is significantly down-regulated when plastid biogenesis is inhibited (Kakizaki et al., 2009; Waters et al., 2009). This regulation is GUN1-dependent, as the gun1-101 mutation has been shown to abolish the down-regulation of GLK1 (Kakizaki et al., 2009). We examined if the level of GLK1 mRNA correlates with the amount of GLK1 protein when plastids are damaged (Fig. 4). When wild-type Arabidopsis is treated with norflurazon (NF), the accumulation of GLK1 decreased dramatically (Fig. 4, A and B). This is in part attributable to the fact that the expression of GLK1 is significantly down-regulated in NF-treated wild-type plants (Fig. 4C). In contrast, expression of GLK1 is active when the gun1-101 mutant was treated with NF (Fig. 4C). Intriguingly, the gun1-101 mutant failed to accumulate GLK1 protein in the presence of NF even though GLK1 mRNA is fully expressed (Fig. 4, A and B). We also investigated the effects of lincomycin treatment on the accumulation of GLK1 protein. When wild-type and gun1-101 plants grown in submerged culture system were treated with lincomycin for 5 d, the accumulation of GLK1 was dramatically decreased in both plants (Fig. 4, D and E). Similar to NF-treated wild-type plants, the effects of lincomycin on the expression of GLK1 mRNA in wild-type was moderate compared to those on the accumulation of GLK1 protein (Fig. 4, D to F). In contrast, the GLK1 mRNA was fully expressed in gun1-101 mutant, suggesting that inhibitor-treated gun1-101 mutant down-regulates the level of GLK1 protein other than the transcriptional regulation of GLK1 mRNA.

Figure 4.

Effects of inhibitor treatment and ppi2-2 mutation on GLK1 accumulation. A, Immunoblot analysis of GLK1 protein in wild-type and gun1-101 mutant plants treated with NF. After growth under normal conditions for 3 d, plants were treated with 1 μM NF (+) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, −) under continuous light for 5 d. Extracted proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were probed with antibodies against GLK1 (upper panel) and actin (lower panel), respectively. B, Quantification of GLK1 protein levels in each sample shown in A. GLK1 protein levels were quantified using image acquisition software and normalized to actin levels. The GLK1 protein level in DMSO-treated wild-type plants was set to 1. C, Quantitative analysis of GLK1 mRNA expression in wild-type and gun1-101 mutant plants treated with NF (+) or DMSO (−). Wild-type and gun1-101 plants were treated with either NF or DMSO as described for (A). The mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR, and expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. Error bars represent 1 se of the mean (n = 3). The expression level in DMSO-treated wild-type plants was set to 1. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test. D, Immunoblot analysis of GLK1 protein in wild-type and gun1-101 mutant plants treated with lincomycin (Lin). Plants grown in a liquid MS medium (see “Materials and Methods”) were treated with 0.5 mM Lin (+) or distilled water (DW, −) under continuous light for 5 d. Extracted proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were probed with antibodies against GLK1 (upper panel) and actin (lower panel), respectively. E, Quantification of GLK1 protein levels in each sample shown in (D). The GLK1 protein level in DW-treated wild-type plants was set to 1. F, Quantitative analysis of GLK1 mRNA expression in the wild-type and gun1-101 mutant plants treated with Lin (+) or DW (−). The mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR, and expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. Error bars represent 1 SE of the mean (n = 3). The expression level in DW-treated wild-type plants was set to 1. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test. G, Immunoblot analysis of GLK1 protein in wild-type and homozygous ppi2-2. Plants were grown under continuous light for 15 d. Extracted proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were probed with antibodies against GLK1 (upper panel) and actin (lower panel), respectively. H, Quantification of GLK1 protein levels in each sample shown in (G). The GLK1 protein level in wild-type plants was set to 1. I, Quantitative analysis of GLK1 mRNA expression in wild-type and ppi2-2 mutant. The mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR, and expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. Error bars represent 1 se of the mean (n = 3). The expression level in wild-type plants was set to 1. *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test. ns, not significant; WT, wild type.

We also examined if damaged plastids caused by the plastid protein import2-2 (ppi2-2) mutation affect the accumulation of GLK1. The homozygous ppi2-2 mutant lacks the major protein import receptor of chloroplasts and exhibits a severe albino phenotype (Kakizaki et al., 2009). Consistent with our previous observation, the level of GLK1 mRNA was significantly down-regulated in ppi2-2 mutant (Fig. 4I). However, the level of GLK1 protein in ppi2-2 mutant appeared to be much lower than that of GLK1 mRNA found in the same plants (Fig. 4, G and H). This observation was similar to NF- or Lin-treated wild-type plants.

Taken together, these data suggest that damaged plastids directly regulate the accumulation of GLK1 protein at the posttranscriptional level. Furthermore, this regulation caused by NF or Lin treatment does not seem to require GUN1.

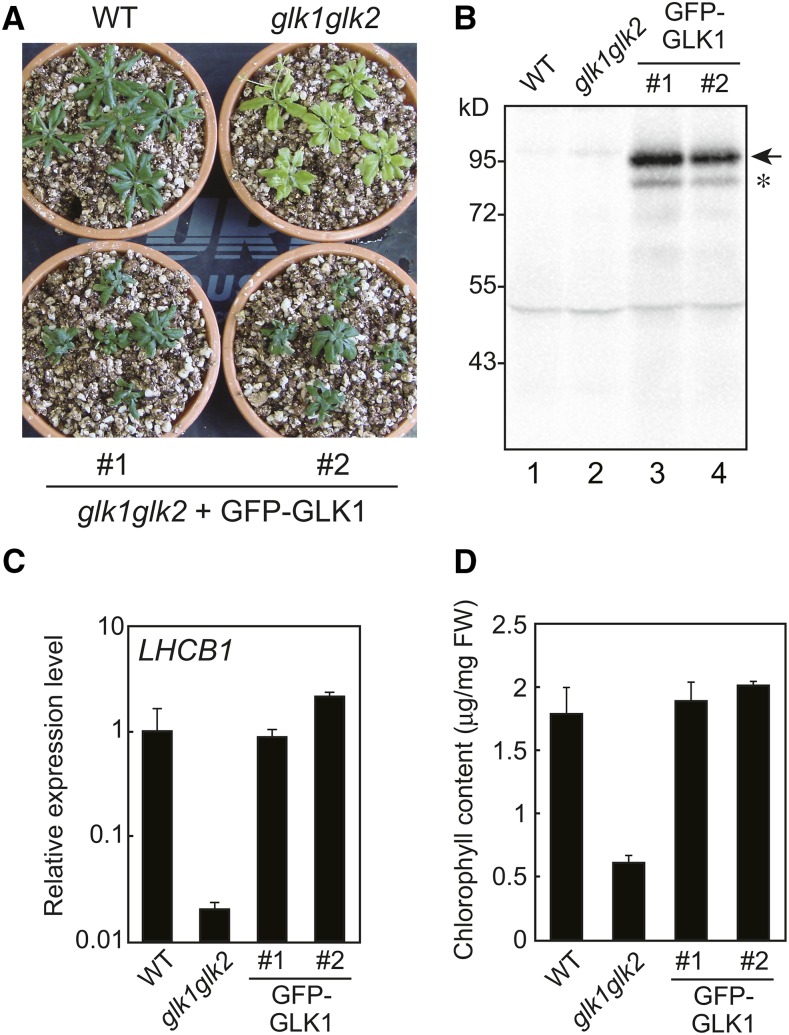

GLK1 Protein Forms High Mr Complexes in the Nucleus

To further investigate the regulation of GLK1 at the protein level, we attempted to generate a glk1glk2 line complemented with GFP-GLK1. A previous study suggested that GFP-GLK1 is highly unstable (Waters et al., 2008). To avoid degradation due to undesirable conformation of the fusion protein, we inserted a flexible linker (Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ser) between GFP and GLK1 (Evers et al., 2006). The GFP-GLK1 chimeric construct was transformed into a glk1glk2 double mutant. We obtained transgenic lines with a phenotype similar to the wild type (Fig. 5), indicating that the GFP-GLK1 gene complements the glk1glk2 phenotype. When total protein was extracted from these plants and probed with antibodies against GFP, a band was detected with the apparent molecular mass of approximately 100 kD (Fig. 5B), indicating that the protein was expressed as the chimeric protein. Although these transgenic plants accumulated a small amount of degradation products (an asterisk in Fig. 5B), the major product appeared to be the full length GFP-GLK1 (an arrow in Fig. 5B). Similar to the observation of a GLK1 overexpressing line (Leister and Kleine, 2016), the expression of LHCB1 in these lines (Fig. 5C) were comparable to that in wild-type (line 1) or even higher than that in wild type (line 2). In these transgenic plants, the levels of chlorophyll content were comparable to those in the wild type (Fig. 5D). Hence, we concluded that the GFP-GLK1 protein expressed in these transgenic plants was functional.

Figure 5.

Expression of GFP-GLK1 in the glk1glk2 mutant. A, Representative phenotype of the glk1glk2 mutant transformed with GFP-GLK1 construct. Transformed plants were first grown on MS plates containing Hygromycin B for 2 weeks, transferred to soil, and allowed to grow for another 2 weeks. Wild-type and glk1glk2 plants were grown on MS plates without antibiotics and then transferred to soil. B, Immunoblot analysis of GFP-GLK1. Total proteins were extracted from wild-type, glk1glk2, and transformed plants, and probed with antibodies against GFP. GFP-GLK1 is indicated by an arrow. An asterisk indicates the position of degraded GFP-GLK1. C, Expression analysis of LHCB1 in wild-type, glk1glk2, and transformed plants. The mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR, and expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. Error bars represent 1 se of the mean (n = 3). The expression level in wild-type plants was set to 1. D, Total chlorophyll content in wild-type, glk1glk2, and transformed plants. Error bars represent 1 se of the mean (n = 3). FW, Fresh weight. WT, wild type.

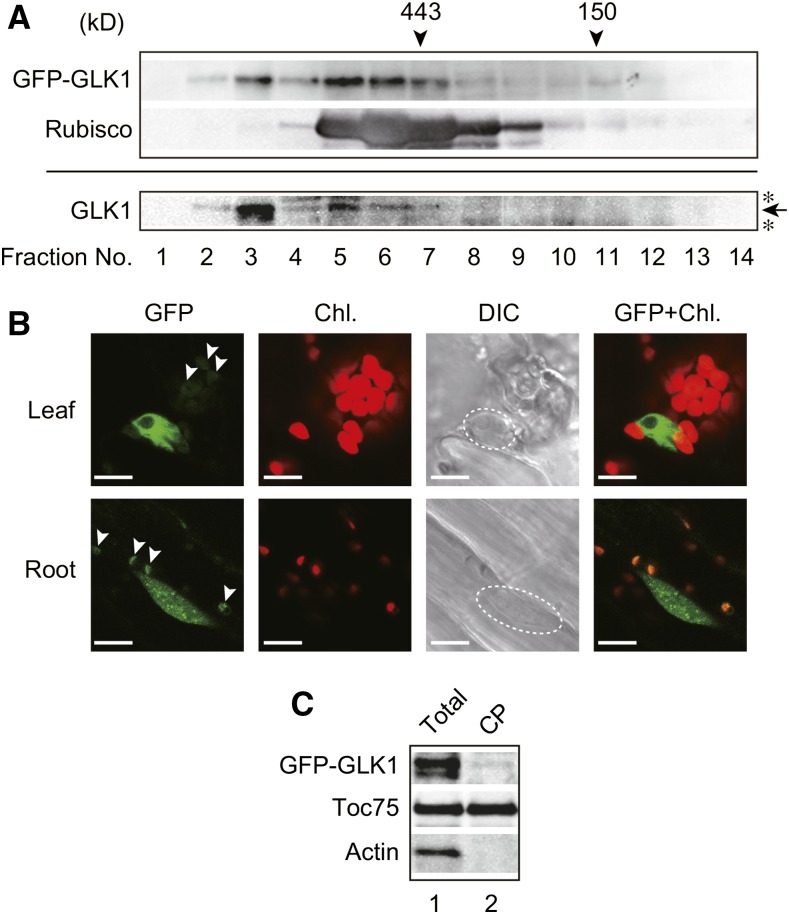

We next investigated the nature of GFP-GLK1 in more detail, by performing gel-filtration chromatography using the protein extract isolated from the glk1glk2 mutant complemented with GFP-GLK1 (Fig. 6). When total proteins were resolved by gel-filtration chromatography, GFP-GLK1 appears to form high Mr Complexes (Fig. 6A, upper panel). The high Mr complexes were also observed in the GLK1ox line, and the apparent molecular masses of GLK1 complexes were similar to those of GFP-GLK1 complexes (Fig. 6A, lower panel). This finding suggests that GLK1 forms heteromeric complexes with other proteins such that both GLK1 and GFP-GLK1 complexes exhibit similar molecular masses. Furthermore, NF treatment did not affect the apparent molecular masses of GFP-GLK1 complexes (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Figure 6.

Identification of GFP-GLK1 complexes by gel-filtration chromatography and intracellular localization of GFP-GLK1. A, Gel-filtration chromatography of GFP-GLK1 and GLK1 proteins expressed in Arabidopsis. Total protein extracts from GFP-GLK1 transformed glk1glk2 plants (upper panel) and GLK1ox plants (lower panel) were resolved by gel-filtration chromatography on a Sephacryl S-300 HR column. The molecular masses of the standard proteins are indicated by arrowheads. To verify the validity of chromatography, the distribution of Rubisco (approximately 550 kD) was also investigated. Proteins in each fraction were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against GLK1 or Rubisco holoenzyme. An arrow indicates the position of GLK1, and asterisks indicate nonspecific bands. B, Localization of GFP-GLK1 protein in Arabidopsis leaf and root cells. Leaf (upper) and root (lower) tissues of transgenic plants expressing GFP-GLK1 in glk1glk2 background were observed using a confocal laser-scanning microscope LSM 700. Dashed lines in DIC images indicate the location of the nucleus. Arrowheads indicate likely autofluorescence of plastids, rather than GFP signals. C, Detection of GFP-GLK1 in chloroplasts. Total protein extracts (lane 1) and chloroplast proteins (lane 2) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with antibodies against GLK1 (top) and Toc75 (middle). As the negative control, the membrane was also probed with an anti-actin antibody (bottom). Chl., chlorophyll autofluorescence; DIC, differential interference contrast image; GFP, GFP fluorescence; GFP+Chl., overlap of the GFP and Chl. images.

A previous study showed that GLK2 localized in the nucleus of Arabidopsis protoplasts (Rauf et al., 2013). Hence, we also investigated the intracellular localization of GFP-GLK1 protein in the complemented line. As shown in Figure 6B, GFP-GLK1 localizes in the nucleus. Consistent with the previous observation in GLK1-overexpressing plants (Kobayashi et al., 2012), GFP-GLK1 plants also exhibited excess accumulation of chlorophyll in root plastids (Fig. 6B). This observation is attributable to the function of GLK1, as GFP control plants do not show chlorophyll fluorescence under the same conditions (Supplemental Fig. S2B). Furthermore, we sometimes observed green fluorescence from plastids of GFP-GLK1 plants (arrowheads in Fig. 6B). Under the same conditions, we did not observe plastid-derived green fluorescence in GFP control plants (Supplemental Fig. S2B). However, chloroplasts isolated from GFP-GLK1 plants did not contain GFP-GLK1 sufficient to demonstrate localization in chloroplasts (Fig. 6C). Hence, we concluded that the majority of GFP-GLK1 localizes to the nucleus. Green fluorescence on plastids appears to be derived from enhanced autofluorescence of plastids due to the excess accumulation of chlorophyll within plastids of GFP-GLK1-expressing plants (Fig. 5D).

GFP-GLK1 Is Polyubiquitinated In Vivo

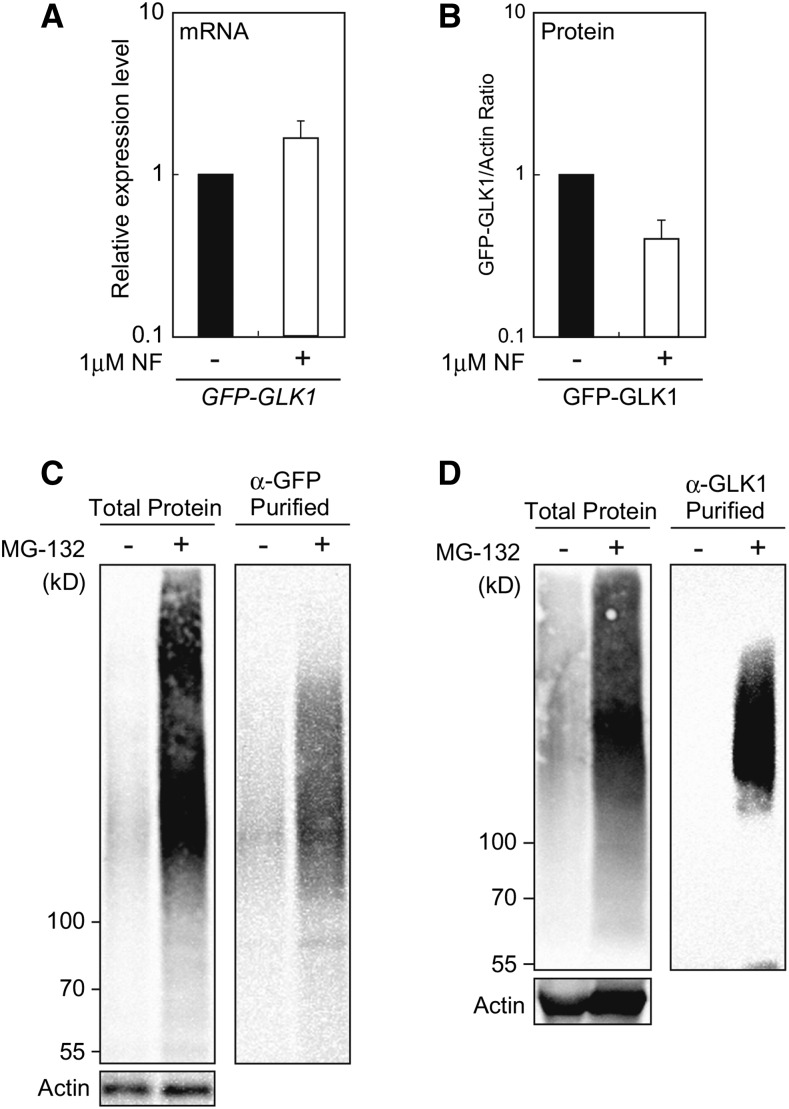

The fact that NF treatment did not affect the context of GFP-GLK1 complexes (Supplemental Fig. S2) prompted us to hypothesize that GLK1 is most likely regulated by degradation rather than partitioning within the cell in response to plastid signals. To further confirm this hypothesis, we investigated if GFP-GLK1 accumulation is regulated by damaged plastids. The glk1glk2 mutants complemented with GFP-GLK1 were treated with NF. In addition to lines 1 and 2, we also included additional two lines that exhibited moderate complementation phenotype with larger stature and light-green coloration (Supplemental Fig. S3). Using those four independent transgenic lines, we confirmed that the expression of GFP-GLK1 mRNA in NF-treated plants was moderately up-regulated regardless of the degree of complementation (Fig. 7A and Supplemental Fig. S3). In contrast, the accumulation of GFP-GLK1 protein was consistently decreased in the NF-treated plants (Fig. 7B and Supplemental Fig. S3). These results further substantiate the idea that the GLK1 levels are directly regulated by degradation of this protein in response to plastid signals.

Figure 7.

Effects of NF and MG-132 on GFP-GLK1 in the transformed plants. A, Effects of NF on the expression of GFP-GLK1 in the transformed glk1glk2 plants. After growth under normal conditions for 3 d, plants were treated with 1 μM NF (+) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, −) under continuous light for 5 d. The mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR, and expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. The graph shows the average of four independent transgenic lines shown in Supplemental Fig. S3. Error bars represent 1 SE of the mean (n = 4). B, Accumulation of GFP-GLK1 in the glk1glk2 double mutant transformed with GFP-GLK1. Plants were treated with either 1 μM NF or DMSO as described for (A). Extracted proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were probed with antibodies against GLK1 or actin (Supplemental Fig. S3B). GLK1 protein levels were quantified using image acquisition software and normalized to actin levels. The graph shows the average of four independent transgenic lines shown in Supplemental Fig. S3. Error bars represent 1 se of the mean (n = 4). C and D, Accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated GFP-GLK1 in plants treated with MG-132. Arabidopsis plants expressing GFP-GLK1 were cultured in a liquid MS medium for 2 weeks. Plants were then treated with 50 μM MG-132 (+) in a liquid culture for 12 h. As the control, plants were also treated with DMSO (−) for the same duration. Total proteins were extracted from MG-132 or DMSO-treated plants, and GFP-GLK1 protein was affinity purified using antibodies against either GFP (C) or GLK1 (D). The starting material (1% of the total) and eluates were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were probed with monoclonal antibody against the multiubiquitin chain. Actin amounts confirmed equal loading of starting material.

We next explored the possible mechanism by which GLK1 degradation is regulated. One possible regulatory mechanism is polyubiquitination of GLK1 and its subsequent degradation by a proteasome. To test the involvement of ubiquitin-proteasome system in the regulation of GLK1, we examined the polyubiquitination of GFP-GLK1 in vivo using an antibody against the multiubiquitin chain. The glk1glk2 plants complemented with GFP-GLK1 were grown in a whole-plant submerged culture system (Ohyama et al., 2008). After cultivation for 2 weeks, plants were treated with either DMSO or a proteasome inhibitor, MG-132. Addition of MG-132 induced the accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins (Fig. 7C, left panel). When affinity-purified GFP-GLK1 was probed with antibody against multiubiquitin chain, we observed that MG-132-tretaed plants indeed accumulated polyubiquitinated GFP-GLK1 (Fig. 7C, right panel). Specific polyubiquitination of GFP-GLK1 was further confirmed by immunoprecipitation using anti-GLK1 antibodies (Fig. 7D).

Taken together, these data indicate that GLK1 is subjected to ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent regulation.

Proteasome-Dependent Pathway Regulates the Accumulation of GLK1 Protein in Response to Plastid Signals

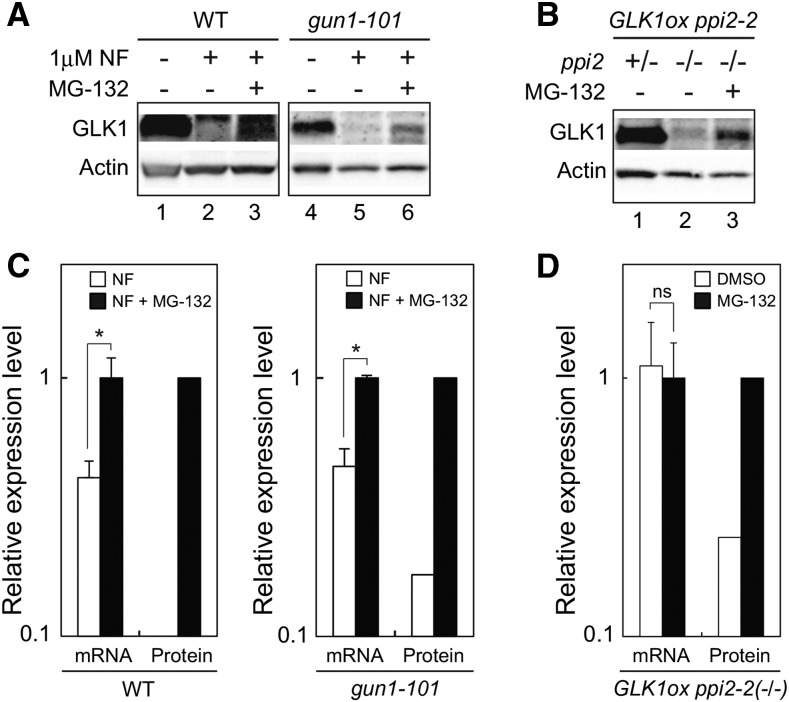

To further prove that ubiquitin-proteasome system directly regulates the accumulation of GLK1 in response to plastid signals in vivo, we investigated the effects of MG-132 treatment on the accumulation of GLK1 in wild type and gun1-101. Wild-type and gun1-101 plants grown in a whole-plant submerged culture system were treated with NF for 6 d. Then, plants were further treated with DMSO or MG-132 for 18 h.

Consistent with the data obtained from plants grown on MS plates (Fig. 4A), NF-treatment in submerged culture dramatically decreased the level of GLK1 in wild type and gun1-101 (Fig. 8). However, those plants partially restored GLK1 accumulation when they were subsequently treated with MG-132 (Fig. 8A). Unlike transcriptional regulation of GLK1 in response to plastid signals (Fig. 4C), it appeared that this regulation of GLK1 did not require GUN1 (Fig. 8A). We also investigated the effects of MG-132 on GLK1 accumulation using a ppi2-2 mutant overexpressing GLK1 (GLK1ox ppi2-2). The expression of GLK1 in GLK1ox ppi2-2 is approximately 10 times higher than that in wild type (Kakizaki et al., 2009), allowing us to detect GLK1 protein easily. As shown in Figure 8B, the level of GLK1 protein in the homozygous GLK1ox ppi2-2(−/−) was dramatically decreased compared to that in heterozygous GLK1ox ppi2-2(+/−; Fig. 8B, compare lanes 1 and 2). However, the decrease of GLK1 accumulation caused by homozygous ppi2-2 mutation was attenuated by MG-132 treatment (Fig. 8B, lane 3). These data indicate that the decrease of GLK1 caused by multiple plastid signals can be attenuated by MG-132 treatment. MG-132 treatment up-regulated the level of GLK1 mRNA in NF-treated wild-type and gun1-101 plants (Fig. 8C). Nonetheless, this increase was insufficient to fully explain the increase of GLK1 protein in those plants (Fig. 8C, compare mRNA with protein). The level of GLK1 mRNA was unaffected in the homozygous GLK1ox ppi2-2(−/−) mutant in response to MG-132 treatment (Fig. 8D). This further supports the idea that the increase of GLK1 in MG-132 treated plants results from inhibition of GLK1 degradation by ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

Figure 8.

Effects of MG-132 on GLK1 accumulation in vivo. A, Effects of MG-132 on the accumulation of GLK1 in wild-type and gun1-101 plants treated with NF. Plants were treated with DMSO (lanes 1 and 4) for 4 d or with NF for 6 d. The NF-treated plants were further treated with additional DMSO (lanes 2 and 5) or 50 μM MG-132 (lanes 3 and 6) for 18 h. Extracted proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were probed with antibodies against GLK1 or actin. Note that the exposure time to capture GLK1 signals in wild-type lanes was longer than that in gun1-101 lanes. B, Effects of MG-132 on the accumulation of GLK1 in ppi2-2 mutant overexpressing GLK1 (GLK1ox ppi2-2). Note that only the plants carrying homozygous ppi2 genotype (ppi2 −/−) exhibit damaged plastids and albino phenotype. The GLK1ox ppi2-2 mutant was grown on plates for 7 d. Then, plants were transferred to liquid MS medium. The heterozygous GLK1ox ppi2-2(+/−) plants (green phenotype) were grown in liquid MS medium for 6 d under continuous light and then subjected to DMSO treatment for 18 h. The homozygous GLK1ox ppi2-2(−/−) plants (albino phenotype) were grown in liquid MS medium for 10 d under continuous light and then treated with either DMSO (lane 2) or 50 μM MG-132 (lane 3) for 18 h. Extracted proteins were then resolved by SDS-PAGE, and proteins were probed with antibodies against GLK1 or actin. C, Quantification of GLK1 mRNA and GLK1 protein levels in NF-treated plants (NF) and both NF and MG-132-treated plants (NF + MG-132) shown in (A). GLK1 protein levels were quantified using image acquisition software and normalized to actin levels. The mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR, and the expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. The expression levels in wild-type (left) or gun1-101 (right) plants treated with both NF and MG-132 was set to 1. Error bars shown in mRNA data represent 1 SE of the mean (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 as determined by Student’s t-test. D, Quantification of GLK1 mRNA and GLK1 protein levels in the GLK1ox ppi2-2(−/−) mutant treated with DMSO or MG-132 shown in (B). GLK1 protein levels were quantified using image acquisition software and normalized to actin levels. The mRNA levels were analyzed by real-time PCR, and the expression levels were normalized to that of ACTIN2. The expression level in GLK1ox ppi2-2(−/−) plants treated with MG-132 was set to 1. Error bars shown in mRNA data represent 1 se of the mean (n = 3). ns, not significant. WT, wild type.

Taken together, these data suggest that the plastid signals regulate the accumulation of GLK1 through the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Furthermore, unlike the transcriptional regulation of GLK1 in response to plastid signals, this regulation does not require GUN1 function.

DISCUSSION

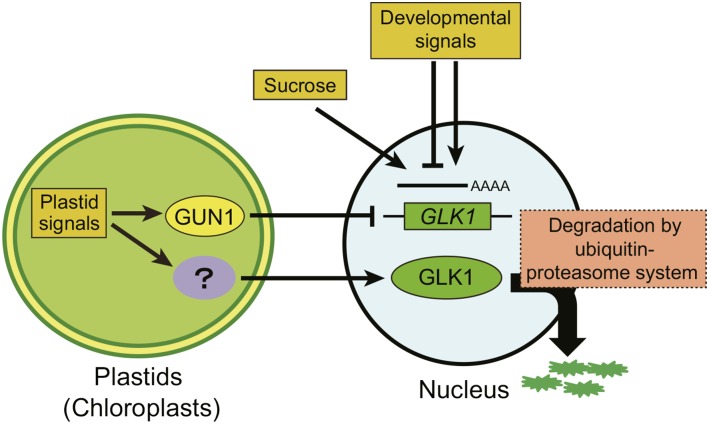

The GLK1 family of transcription factors is a key component in signal transduction from plastids to the nucleus (Inaba et al., 2011; Chi et al., 2013; Jarvis and López-Juez, 2013). Previous studies have demonstrated that the expression of GLK1 is regulated by plastid signals through GUN proteins (Kakizaki et al., 2009; Waters et al., 2009). To elucidate how GLK1 protein levels are regulated within the cell, we characterized the regulatory mechanism of GLK1 using specific antibodies and a chimeric GLK1 protein fused to GFP. Suc-dependent and tissue-specific accumulation of GLK1 protein was primarily regulated at the transcriptional level. In contrast, alteration of GLK1 accumulation in response to plastid signals was also regulated at the posttranscriptional level (Fig. 4). We demonstrated that the ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates accumulation of GLK1 protein (Figs. 7 and 8). Our results suggest that plastids regulate the accumulation of GLK1 at multiple levels, allowing the cell to optimize plastid development in response to developmental and environmental cues. We summarize a possible mechanism by which the accumulation of GLK1 is regulated in response to developmental and metabolic cues (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Model for the regulation of GLK1 by multiple mechanisms. Both developmental signals and Suc regulate the accumulation of GLK1 protein through transcriptional regulation of GLK1 gene. Plastid signals derived from damaged plastids also regulate the expression of GLK1 through the activity of GUN1. Meanwhile, plastid signals regulate the accumulation of GLK1 at protein level. Although the components involved in this regulation remain to be identified, the ubiquitin-proteasome system appears to participate in this regulation.

At least two mechanisms involving the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway have been shown to regulate chloroplast protein import and biogenesis (Jarvis and López-Juez, 2013). The first mechanism is the direct regulation of protein translocation machinery. In this mechanism, a RING-type ubiquitin ligase of the chloroplast outer membrane, SP1, directly regulates the context of the TOC complex (Ling et al., 2012). The second mechanism involves degradation of unimported chloroplast precursor proteins. This mechanism involves the cytosolic heat shock cognate, Hsc70-4, and its interacting E3-ubiquitin ligase, CHIP (Lee et al., 2009). Those proteins together mediate the degradation of unimported chloroplast precursor proteins through the ubiquitin-proteasome system. This quality-control mechanism may also involve N-acetylation of unimported precursors (Bischof et al., 2011). Now, we propose a third mechanism regulating chloroplast biogenesis through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. That is, the transcription factor indispensable in the accumulation of photosynthetic proteins, GLK1, is degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. In this mechanism, we propose that the damaged plastids send some signal to activate the ubiquitin-proteasome system, thereby degrading GLK1 (Fig. 9). Taken together, these results suggest that the ubiquitin-proteasome system simultaneously regulates the level of GLK1 and precursors of photosynthetic proteins, thereby optimizing the rate of photosynthetic protein import into chloroplasts in response to intracellular or environmental signals.

According to a previous observation, fluorescence of GLK1-GFP chimeric protein was undetectable even though the construct complemented the glk1glk2 phenotype (Waters et al., 2008). Furthermore, GLK1-GFP fusion protein could not be detected by immunoblotting (Waters et al., 2008). To overcome these challenges, we introduced a flexible linker (Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ser) between GFP and GLK1. This made it possible to detect GFP-GLK1 protein and to analyze the behavior of GLK1 in vivo. Our GFP-GLK1 construct fully complemented LHCB1 expression and chlorophyll accumulation in the glk1glk2 mutant (Fig. 5, C and D). Because the transcription factor PTM localizes to the chloroplast envelope and targets to the nucleus in response to plastid signals (Sun et al., 2011), we suspected that GFP-GLK1 also localizes to the outer envelope membrane of chloroplasts. However, our results indicate that GFP-GLK1 localizes to the nucleus primarily (Fig. 6B). Hence, unlike PTM, nuclear-plastid partitioning of GLK1 does not play an indispensable role in plastid signaling.

As summarized in Figure 9, the level of GLK1 protein appears to be regulated at the transcriptional level under normal conditions. Consistent with a previous observation (Fitter et al., 2002), GLK1 transcripts predominantly accumulate in aerial tissues but not in roots (Fig. 2C). This expression pattern is reflected by the accumulation of GLK1 protein in each tissue (Fig. 2B). We also observed that Suc positively regulates the expression of GLK1 in Arabidopsis. In a previous study, we showed that plastid signals suppress the transcription of GLK1 in a GUN1-dependent manner (Kakizaki et al., 2009). However, it appears that the ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent regulation predominates over transcriptional regulation. Transcription of GLK1 failed to respond to NF treatment in the absence of GUN1, but the ubiquitin-proteasome system degraded GLK1 regardless of the GLK1 transcript level (Figs. 4 and 7). Meanwhile, it should be noted that the addition of MG-132 did not fully restore the level of GLK1 in all the plants tested (Fig. 8). Hence, we do not exclude the possibility that mechanisms other than ubiquitin-proteasome system also participate in the regulation of GLK1. Intriguingly, a gun1-101 mutant treated with NF still exhibited down-regulation of LHCB1 expression, whereas the expression of GLK1 was virtually unaffected by NF treatment (Kakizaki et al., 2009). Hence, our finding that GLK1 is degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system in response to plastid signals nicely explains the moderate repression of LHCB1 observed in the gun1-101 mutant.

Whether transcription factors other than GLK1 are regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system in response to plastid signals remains unclear. It is well known that the transcription factor HY5 is subjected to ubiquitin-proteasome-dependent regulation during photomorphogenesis (Osterlund et al., 2000). In the dark, COP1 protein interacts with HY5 in the nucleus to target HY5 for degradation. COP1 redistributes to the cytosol upon illumination, thereby allowing HY5 to facilitate photomorphogenesis. Coincidently, it has been shown that genetic interaction between HY5 and GLKs plays a key role in coordinating gene expression required for chloroplast biogenesis (Kobayashi et al., 2012). Furthermore, the amount of ABI4 also seems to be in part regulated by proteasome degradation (Finkelstein et al., 2011). It remains to be characterized if HY5 and ABI4 are also regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system in response to plastid signals. Nonetheless, the genetic and functional link between GLKs and these transcription factors suggests that the ubiquitin-proteasome system may be important in regulating other transcription factors in plastid signaling pathways.

Our gel filtration chromatography results reveal that GLK1 forms high Mr complexes with other proteins. The components involved in high Mr complexes remain to be identified. To date, a few proteins have been shown to associate with GLKs. A search for proteins that interact with G-box binding factors led to the identification of GLKs as possible interacting partners (Tamai et al., 2002). Likewise, yeast two-hybrid screening of proteins interacting with the NAC transcription factor ORE1 identified GLKs as interacting partners (Rauf et al., 2013). Interaction of GLKs with other transcription factors appears to affect the transcription of target genes. In addition to transcription factors, proteins involved in GLK1 degradation, such as ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, are likely to participate in these molecular complexes containing GLK1. As illustrated by the role of COP1 in HY5 degradation (Osterlund et al., 2000), ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes that associate with GLKs may determine specific degradation of GLK1 in response to plastid signals. Hence, it is of great interest to identify proteins involved in high Mr complexes of GLK1.

In summary, we demonstrated that a proteasome-dependent pathway regulates the accumulation of GLK1 protein in response to plastid signals in Arabidopsis. In addition to transcriptional regulation of GLK1 through GUN1, it appears that the ubiquitin-proteasome dependent degradation of GLK1 plays a pivotal role in plastid signaling. Taken together, these results suggest that plastids have evolved multiple mechanisms to optimize the import rate of nuclear-encoded plastid proteins in response to plastid signals, thereby regulating chloroplast biogenesis appropriately.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

All experiments were performed on Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) accessions Columbia (Col-0). The glk1, glk2, and glk1glk2 mutants were described in Fitter et al. (2002) and obtained from the ABRC. The gun1-101 mutant was described in Kakizaki et al. (2009). GLK1ox, GLK1ox ppi2-2(+/−), and GLK1ox ppi2-2(−/−) plants were segregated from a PPI2/ppi2 line overexpressing GLK1 (Kakizaki et al., 2009). Plants were grown on soil (expanded vermiculite) or on 0.5% agar medium containing 1% Suc and 0.5× MS salts. To synchronize germination, all seeds were kept at 4°C for 2 to 3 d after sowing. Unless specified, plants were grown under continuous white light (60 ∼ 80 μmol·m−2·s−1) at 22°C and 50% relative humidity in a growth chamber (LHP-220S or LHP-350S; NK Systems).

Tissue-specific expression of GLK1 mRNA and GLK1 protein was examined using Arabidopsis grown on soil under continuous light. Each tissue was harvested at d 6 (cotyledon), d 28 (rosette leaves and roots), and d 42 (stem, cauline leaves and flower bud) after transfer to a growth chamber. To test the effect of Suc on expression (Fig. 3), wild-type and gun1-101 mutant were grown on 0.5× MS plates containing either Suc (1% or 2%) or mannitol (1.06%, equivalent to 2% Suc in terms of molar concentration). Because plants grown on Suc grew faster than those grown on mannitol-containing or Suc-depleted plates, we harvested each sample 12 d (1% and 2% Suc) or 13 d (Suc-depleted and mannitol) after the transfer of plates to the growth chamber. For the NF treatment in Figs. 4 and 7, plants were grown under normal conditions under continuous white light (approximately 100 μmol·m−2·s−1) for 3 d and then treated with 1 μm NF or DMSO under continuous light for another 5 d.

For lincomycin treatment, wild type and gun1-101 were grown on MS plates for 7 d and then transferred to liquid MS medium according to Ohyama et al. (2008). After cultivation in liquid MS medium for 3 d, plants were treated with either 0.5 mM lincomycin or distilled water (control) for 5 d. The extracted protein and RNA were analyzed by immunoblotting and real-time PCR, respectively.

Construction of Vectors and Arabidopsis Transformation

To create the NusA-TEV-GLK1-His construct (Supplemental Fig. S1A), GLK1 cDNA was inserted into SpeI and XhoI sites of a pET43.1a vector (Novagen). To introduce the TEV protease cleavage site, a nucleotide sequence that encodes the TEV cleavage site was added at the 5′ end of the primer containing the GLK1 start codon.

To create the GFP-GLK1 construct, GFP and GLK1 cDNAs were amplified separately. To increase conformational flexibility of the chimeric protein, flexible linker DNA encoding Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly-Gly-Ser was added between GFP and GLK1. Both GFP and GLK1 fragments were subcloned simultaneously into a pUC vector using the In-Fusion HD cloning system (Takara). The resulting plasmid, pUC-GFP-GGSGGS-GLK1, was used as the template to further amplify GFP-GLK1 using PCR. The amplified fragment was inserted into NcoI and NheI sites of the pCAMBIA1301 vector. The pCAMBIA1301 construct was introduced into Arabidopsis cv Col-0 via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Primer sequences used for vector construction are shown in Supplemental Table S1.

Purification of GLK1-His

For bacterial expression, pET43.1a-GLK1-His was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Expression was induced with 0.2 mm IPTG overnight at 20°C, and both soluble and insoluble fractions were recovered to obtain the NusA-GLK1-His fusion protein. The insoluble NusA-GLK1-His was purified using Ni2+ affinity chromatography and refolded by gel filtration. The fusion protein was then cleaved into NusA and GLK1-His (Supplemental Fig. S1B, lane 1). The GLK1-His protein (Supplemental Fig. SB, lane 2) was further purified using preparative gel electrophoresis (Hayakawa et al., 2001) using a NA-1800 device (Nihon Eido).

Antibodies and Immunoblotting

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against GLK1 were produced using either GLK1-His excised from the gel (Supplemental Fig. S1B, lane 1, arrow) or purified GLK1-His (Supplemental Fig. S1B, lane 2) as the antigen. To obtain purified antibodies against GLK1, serum was first applied to NusA-sepharose to deplete NusA antibodies, and further applied to NusA-TEV-GLK1-His-Sepharose. The bound antibodies were eluted with 0.2 M Gly-HCl buffer, pH 2.2. Monoclonal antibody against actin was purchased from CHEMICON. Polyclonal antibodies against GFP were described in Ito-Inaba et al. (2016). Immunolabeled proteins were detected with a Lumino-image analyzer (AE-6972C; ATTO) using chemiluminescence reagents. Signal was quantified using image acquisition software (CS Analyzer; ATTO).

Purification of Polyubiquitinated GFP-GLK1

The glk1glk2 mutant complemented with GFP-GLK1 was grown in liquid MS medium according to Ohyama et al. (2008). After cultivation for 2 weeks, plants were treated with either DMSO or a proteasome inhibitor, 50 μM MG-132, for 12 h. GFP-GLK1 was recovered using the μMACS GFP-Tagged Protein Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) or the affinity-purified antibodies against GLK1 bound to protein A sepharose. Total protein extract and purified GFP-GLK1 protein were then resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with an antibody against the multiubiquitin chain (clone FK2; Cayman Chemical).

Detection of GLK1 in MG-132 Treated Plants

Wild type and gun1-101 were grown on MS plates for 7 d and then transferred to liquid MS medium. After cultivation in liquid MS medium for 3 d, plants were treated with either DMSO for 4 d or 1 μM norflurazon for 6 d. Those plants were further treated with either DMSO or 50 μM MG-132 for 18 h. The extracted protein and RNA were analyzed by immunoblotting and real-time PCR, respectively.

For MG-132 treatment of ppi2-2 mutant overexpressing GLK1 (Fig. 8, B and D), the progeny of heterozygous ppi2-2 carrying homozygous GLK1 transgene was grown on MS plates for 7 d. Then, heterozygous ppi2-2 and homozygous ppi2-2 mutants were separately transferred to liquid MS medium and allowed to grow for 6 d (heterozygous) or 10 d (homozygous). Those plants were further treated with either DMSO or 50 μM MG-132 for 18 h. The extracted protein and RNA were analyzed by immunoblotting and real-time PCR, respectively.

Real-Time PCR Analysis

cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Takara) with random hexamer and oligo d(T) primers. Real-time PCR was performed on a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System (Takara) using SYBR Premix ExTaq II (Takara) as described in Kakizaki et al. (2009). All the real-time PCR analyses were performed using biological triplicate samples. Primers used for real-time PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Transcript levels of each gene were normalized to that of ACTIN2.

Gel Filtration Chromatography

True leaves of Arabidopsis plants were homogenized in a buffer containing 50 mm Tricine-KOH (pH 7.5), 2 mm EDTA, and 400 mm Suc, and the homogenate was centrifuged at 1000g for 5 min. Then, the supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of buffer containing 2% Triton X-100 to solubilize membranes, and centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min. The resulting supernatant was resolved on a Sephacryl S-300HR column equilibrated with TES buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Okawa et al., 2008) using an AKTA-prime chromatography system (GE Healthcare). The first 30 mL of eluate were discarded as void volume because we did not observe any A280. Fractions of 1.5 mL each were collected and the protein in each fraction was precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid. Even-number fractions of the original samples were then resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with antibodies indicated in each panel (Fig. 6A and Supplemental Fig. S1A). Among four glk1glk2 lines complemented with GFP-GLK1, line 2 was used for this analysis.

Quantification of Chlorophyll

Quantification of chlorophyll was performed as described in Kakizaki et al. (2009).

Confocal Microscopy

Leaf and root samples were prepared from the transgenic lines expressing GFP-GLK1 or GFP. The GFP control plant is described in Okawa et al. (2008). Images were captured with a confocal laser-scanning microscope LSM 700 (Carl Zeiss). To directly compare GFP fluorescence and chlorophyll autofluorescence obtained from GFP-GLK1 transgenic plants with those obtained from GFP expressing plants, laser power and detection gain were fixed during a series of analyses.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Expression of GLK1 fusion protein in E. coli.

Supplemental Figure S2. Localization of GFP-GLK1 and GFP in Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure S3. Analysis of glk1glk2 mutants complemented with GFP-GLK1 gene.

Supplemental Table S1. List of Primers used in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Yoshikatsu Matsubayashi (Nagoya University, Japan) for his helpful suggestions on submerged culture systems. We also thank Ms. Saori Hamada for her technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Program to Disseminate Tenure Tracking System (to T.I. and Y.I.-I.), the Strategic Young Researcher Overseas Visits Program for Accelerating Brain Circulation (to Y.S., M.S., and T.I.), Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (25850073 to T.I. and 26850065 to Y.I.-I.), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (15K07843 to T.I.) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), a grant for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the University of Miyazaki (to T.I. and Y.I.-I.), and the Inamori Foundation (to Y.I.-I.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Bischof S, Baerenfaller K, Wildhaber T, Troesch R, Vidi PA, Roschitzki B, Hirsch-Hoffmann M, Hennig L, Kessler F, Gruissem W, Baginsky S (2011) Plastid proteome assembly without Toc159: photosynthetic protein import and accumulation of N-acetylated plastid precursor proteins. Plant Cell 23: 3911–3928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KX, Mabbitt PD, Phua SY, Mueller JW, Nisar N, Gigolashvili T, Stroeher E, Grassl J, Arlt W, Estavillo GM, Jackson CJ, Pogson BJ (2016) Sensing and signaling of oxidative stress in chloroplasts by inactivation of the SAL1 phosphoadenosine phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: E4567–E4576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi W, Sun X, Zhang L (2013) Intracellular signaling from plastid to nucleus. Annu Rev Plant Biol 64: 559–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottage A, Mott EK, Kempster JA, Gray JC (2010) The Arabidopsis plastid-signalling mutant gun1 (genomes uncoupled1) shows altered sensitivity to sucrose and abscisic acid and alterations in early seedling development. J Exp Bot 61: 3773–3786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estavillo GM, Crisp PA, Pornsiriwong W, Wirtz M, Collinge D, Carrie C, Giraud E, Whelan J, David P, Javot H, Brearley C, Hell R, et al. (2011) Evidence for a SAL1-PAP chloroplast retrograde pathway that functions in drought and high light signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 3992–4012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers TH, van Dongen EM, Faesen AC, Meijer EW, Merkx M (2006) Quantitative understanding of the energy transfer between fluorescent proteins connected via flexible peptide linkers. Biochemistry 45: 13183–13192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R, Lynch T, Reeves W, Petitfils M, Mostachetti M (2011) Accumulation of the transcription factor ABA-insensitive (ABI)4 is tightly regulated post-transcriptionally. J Exp Bot 62: 3971–3979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitter DW, Martin DJ, Copley MJ, Scotland RW, Langdale JA (2002) GLK gene pairs regulate chloroplast development in diverse plant species. Plant J 31: 713–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa M, Hosogi Y, Takiguchi H, Saito S, Shiroza T, Shibata Y, Hiratsuka K, Kiyama-Kishikawa M, Abiko Y (2001) Evaluation of the electroosmotic medium pump system for preparative disk gel electrophoresis. Anal Biochem 288: 168–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba T, Schnell DJ (2008) Protein trafficking to plastids: one theme, many variations. Biochem J 413: 15–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaba T, Yazu F, Ito-Inaba Y, Kakizaki T, Nakayama K (2011) Retrograde signaling pathway from plastid to nucleus. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 290: 167–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito-Inaba Y, Masuko-Suzuki H, Maekawa H, Watanabe M, Inaba T (2016) Characterization of two PEBP genes, SrFT and SrMFT, in thermogenic skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus renifolius). Sci Rep 6: 29440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis P, López-Juez E (2013) Biogenesis and homeostasis of chloroplasts and other plastids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 14: 787–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakizaki T, Matsumura H, Nakayama K, Che FS, Terauchi R, Inaba T (2009) Coordination of plastid protein import and nuclear gene expression by plastid-to-nucleus retrograde signaling. Plant Physiol 151: 1339–1353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakizaki T, Yazu F, Nakayama K, Ito-Inaba Y, Inaba T (2012) Plastid signalling under multiple conditions is accompanied by a common defect in RNA editing in plastids. J Exp Bot 63: 251–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpinski S, Reynolds H, Karpinska B, Wingsle G, Creissen G, Mullineaux P (1999) Systemic signaling and acclimation in response to excess excitation energy in Arabidopsis. Science 284: 654–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Baba S, Obayashi T, Sato M, Toyooka K, Keränen M, Aro EM, Fukaki H, Ohta H, Sugimoto K, Masuda T (2012) Regulation of root greening by light and auxin/cytokinin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 24: 1081–1095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koussevitzky S, Nott A, Mockler TC, Hong F, Sachetto-Martins G, Surpin M, Lim J, Mittler R, Chory J (2007) Signals from chloroplasts converge to regulate nuclear gene expression. Science 316: 715–719 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee DW, Lee Y, Mayer U, Stierhof YD, Lee S, Jürgens G, Hwang I (2009) Heat shock protein cognate 70-4 and an E3 ubiquitin ligase, CHIP, mediate plastid-destined precursor degradation through the ubiquitin-26S proteasome system in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 3984–4001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leister D, Kleine T (2016) Definition of a core module for the nuclear retrograde response to altered organellar gene expression identifies GLK overexpressors as gun mutants. Physiol Plant 157: 297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Q, Huang W, Baldwin A, Jarvis P (2012) Chloroplast biogenesis is regulated by direct action of the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Science 338: 655–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura H, Muramatsu M, Hakata M, Ueno O, Nagamura Y, Hirochika H, Takano M, Ichikawa H (2009) Ectopic overexpression of the transcription factor OsGLK1 induces chloroplast development in non-green rice cells. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 1933–1949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama K, Ogawa M, Matsubayashi Y (2008) Identification of a biologically active, small, secreted peptide in Arabidopsis by in silico gene screening, followed by LC-MS-based structure analysis. Plant J 55: 152–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa K, Nakayama K, Kakizaki T, Yamashita T, Inaba T (2008) Identification and characterization of Cor413im proteins as novel components of the chloroplast inner envelope. Plant Cell Environ 31: 1470–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlund MT, Hardtke CS, Wei N, Deng XW (2000) Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature 405: 462–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paparelli E, Gonzali S, Parlanti S, Novi G, Giorgi FM, Licausi F, Kosmacz M, Feil R, Lunn JE, Brust H, van Dongen JT, Steup M, et al. (2012) Misexpression of a chloroplast aspartyl protease leads to severe growth defects and alters carbohydrate metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 160: 1237–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogson BJ, Woo NS, Förster B, Small ID (2008) Plastid signalling to the nucleus and beyond. Trends Plant Sci 13: 602–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauf M, Arif M, Dortay H, Matallana-Ramírez LP, Waters MT, Gil Nam H, Lim PO, Mueller-Roeber B, Balazadeh S (2013) ORE1 balances leaf senescence against maintenance by antagonizing G2-like-mediated transcription. EMBO Rep 14: 382–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Feng P, Xu X, Guo H, Ma J, Chi W, Lin R, Lu C, Zhang L (2011) A chloroplast envelope-bound PHD transcription factor mediates chloroplast signals to the nucleus. Nat Commun 2: 477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szechyńska-Hebda M, Karpiński S (2013) Light intensity-dependent retrograde signalling in higher plants. J Plant Physiol 170: 1501–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamai H, Iwabuchi M, Meshi T (2002) Arabidopsis GARP transcriptional activators interact with the Pro-rich activation domain shared by G-box-binding bZIP factors. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D, Przybyla D, Op den Camp R, Kim C, Landgraf F, Lee KP, Würsch M, Laloi C, Nater M, Hideg E, Apel K (2004) The genetic basis of singlet oxygen-induced stress responses of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 306: 1183–1185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters MT, Moylan EC, Langdale JA (2008) GLK transcription factors regulate chloroplast development in a cell-autonomous manner. Plant J 56: 432–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters MT, Wang P, Korkaric M, Capper RG, Saunders NJ, Langdale JA (2009) GLK transcription factors coordinate expression of the photosynthetic apparatus in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21: 1109–1128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Savchenko T, Baidoo EE, Chehab WE, Hayden DM, Tolstikov V, Corwin JA, Kliebenstein DJ, Keasling JD, Dehesh K (2012) Retrograde signaling by the plastidial metabolite MEcPP regulates expression of nuclear stress-response genes. Cell 149: 1525–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasumura Y, Moylan EC, Langdale JA (2005) A conserved transcription factor mediates nuclear control of organelle biogenesis in anciently diverged land plants. Plant Cell 17: 1894–1907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.