Genetic perturbation of endogenous gibberellin levels shows unexpected flexibility in the wiring of regulatory networks underlying hormone metabolism and signaling.

Abstract

Although phytohormones such as gibberellins are essential for many conserved aspects of plant physiology and development, plants vary greatly in their responses to these regulatory compounds. Here, we use genetic perturbation of endogenous gibberellin levels to probe the extent of intraspecific variation in gibberellin responses in natural accessions of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). We find that these accessions vary greatly in their ability to buffer the effects of overexpression of GA20ox1, encoding a rate-limiting enzyme for gibberellin biosynthesis, with substantial differences in bioactive gibberellin concentrations as well as transcriptomes and growth trajectories. These findings demonstrate a surprising level of flexibility in the wiring of regulatory networks underlying hormone metabolism and signaling.

The relationship between a phenotype and a specific genetic change, also referred to as expressivity, depends not only on the environment, but also on the genetic background in which a mutation occurs (Dowell et al., 2010; Chandler et al., 2013; Chari and Dworkin, 2013). Although typically treated as a nuisance by laboratory geneticists, such epistatic interactions are not only central to studies of genetic variation in populations, but can also increase our understanding of genetic networks and phenotypic robustness (Félix, 2007; Félix and Wagner, 2008; Paaby et al., 2015; Vu et al., 2015). Similar to its implications for human health (Schilsky, 2010), the accurate prediction of background-dependent phenotypic effects of specific mutations is of great interest to crop breeders.

Gibberellins (GAs) are phytohormones with well documented roles in germination, stem elongation, flowering, and leaf, seed, and fruit development, often in response to environmental changes (Hedden, 2003; Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007; Schwechheimer and Willige, 2009; Claeys et al., 2014). In addition, roles in plant immunity have been discovered (De Bruyne et al., 2014). GA20-oxidase (GA20ox), a rate-limiting enzyme in the GA biosynthesis pathway, catalyzes consecutive oxidation events in the late steps of the formation of active GAs. It uses various intermediates as substrates, including GA12, GA53, GA15, GA44, GA24, and GA19, to finally form GA9 and/or GA20 that are converted into bioactive GAs (Hedden and Thomas, 2012) by GA3-oxidase (GA3ox). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), five genes encode GA20ox enzymes. In the Col-0 background, GA20ox1, 2, and 3 are the dominant forms with an important role in growth and fertility, while GA20ox4 and 5 have minor roles (Plackett et al., 2012). The mutation of GA20ox1, 2, and 3 causes severe dwarfism and sterility (Rieu et al., 2008; Plackett et al., 2012), and overexpression of GA20ox1 has been shown to enhance plant growth as a result of increased GA levels (Huang et al., 1998; Coles et al., 1999; Gonzalez et al., 2010; Nelissen et al., 2012).

Here, to assess natural variation in the ability to respond to changes in GA metabolism, we examined at multiple levels the effect of the ectopic expression of GA20ox1 in 17 Arabidopsis accessions. We found that in terms of leaf growth, the accessions respond differently to the increased expression of GA20ox1, although increased levels of the bioactive GA were quantified in all accessions. Our results indicate that hormone metabolism and signaling are remarkably different in these accessions.

RESULTS

Natural Variation in Growth and Hormone Content

Seventeen accessions from throughout the native range of the species (Supplemental Table S1) were grown for 25 d after stratification (DAS) in soil. Thirteen leaf size-related parameters were measured at rosette (fresh and dry weight, number of leaves, and total rosette area), leaf (first leaf pair area, vascular complexity, and density), and cellular level (stomatal index and density, epidermal pavement cell number, area, and circularity, and endoreduplication index of the first leaf pair). The 17 accessions, including the reference accession Col-0, varied for all parameters (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Table S2), differing more than 2.5-fold in rosette biomass, total rosette area, pavement cell number and area, stomatal density, and vascular complexity. Fresh weight showed a significant positive correlation with dry weight, total rosette area, leaf number, and leaf area and correlated negatively with vascular density and complexity (Supplemental Fig. S1).

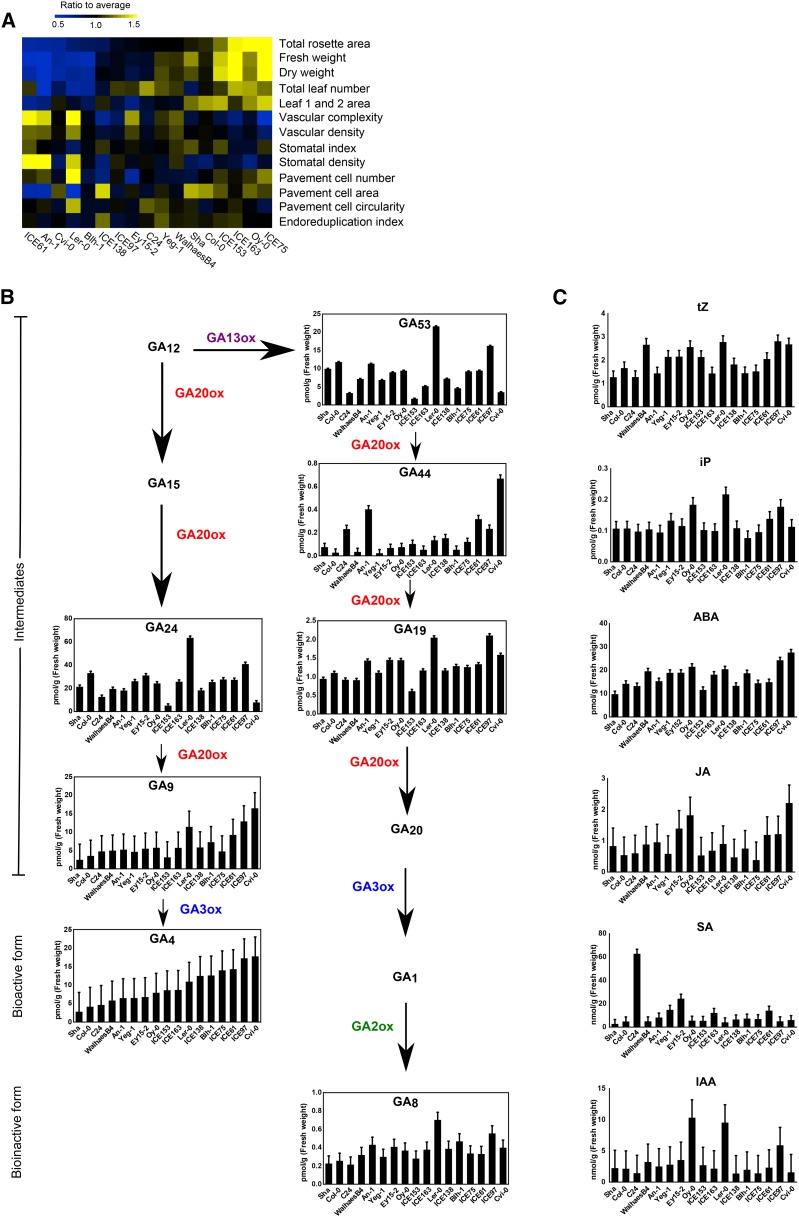

Figure 1.

Variability in leaf size-related parameters and hormone content in 17 Arabidopsis accessions. A, Heat map representing the distance to the average of 17 accessions for 13 leaf size-related parameters (n = 3). Accessions are arranged based on the value of the rosette area. The measurements and calculations can be found in Supplemental Table S2. B, Basal GA levels in 17 accessions. GA biosynthesis (GA20ox and GA3ox) and catabolic (GA2ox) enzymes are indicated with different colors. GA20 and GA1 were not detected. C, Basal levels of cytokinins (tZ and iP), ABA, JA, SA, and IAA in the 17 accessions (n = 3). Error bars represent se.

To examine the potential link existing between growth variation in these accessions and phytohormone accumulation, we measured the levels of biosynthetic intermediates and different bioactive forms of GA, cytokinin, salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), abscisic acid (ABA), and auxin at 12 DAS (Fig. 1, B and C; Supplemental Table S3). GAs, SA, and the auxin indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) varied the most, while cytokinins and ABA varied the least, with JA showing an intermediate degree of changes (Fig. 1, B and C). In addition, we found that the relationships between different GAs and their intermediates, most of which are substrates of GA20ox, were complex. For example, the bioactive GA4 showed a similar profile as its direct precursor, GA9, but the levels of all other intermediates did not parallel that of GA9 and GA4 (Fig. 1B). Similarly, the bioinactive form GA8 and its precursor GA19 showed a similar pattern of accumulation, while their intermediate forms, GA20 and GA1, were not detected (Fig. 1B). These observations suggest a different degree of GA20ox activity for GA biosynthesis in the different accessions. We analyzed the relationship between all the hormones measured using Pearson correlation, and only positive correlations were found between the different plant hormones (Supplemental Table S3; Supplemental Fig. S2).

We uncovered that three hormones, GA, iP, and IAA, were significantly positively correlated with pavement cell number, a leaf growth parameter (Supplemental Fig. S3). Furthermore, one of the GA20ox products, GA19, and the GA bioinactive form, GA8, were negatively correlated with the other two leaf growth parameters, endoreduplication index and stomatal index (Supplemental Fig. S3).

Consequences of GA20ox1 Overexpression in Different Accessions

Overexpression of GA20ox1 in the reference Col-0 background causes similar phenotypes as treatment with exogenous GA, such as larger rosette leaves, longer hypocotyls, increased height, and early flowering (Huang et al., 1998; Coles et al., 1999; Gonzalez et al., 2010; Nelissen et al., 2012; Ribeiro et al., 2012). To investigate natural genetic variation in phenotypic responses to GA level perturbance in Arabidopsis, we introduced the same overexpression construct into 16 additional accessions. In these accessions, the cDNA sequence of the GA20ox1 showed only few differences that led to synonymous substitutions at protein level (Supplemental Fig. S4; Supplemental Table S4). Two to five independent homozygous lines for each accession were selected and grown in soil for 25 d.

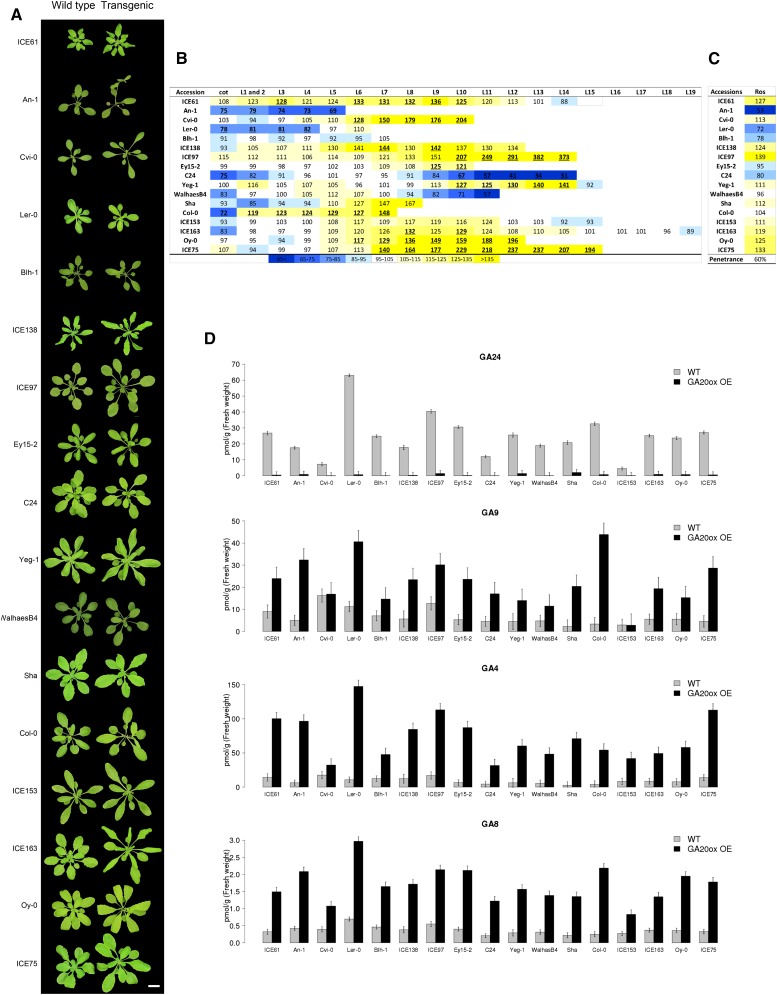

Leaf and Rosette Area

Most, but not all, accessions visibly responded to GA20ox1 overexpression, with altered rosette sizes and longer petioles (Fig. 2A). Importantly, the response was not always in the same direction. For example, whereas in the majority of accessions, the area of younger leaves was increased, in five accessions (An-1, Ler-0, Blh-1, C24, and WalhaesB4) these leaves were smaller as compared with the corresponding wild-type controls (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. S5; Supplemental Tables S5 and S6). Overall, for 10 accessions, transgenics had larger rosettes (Fig. 2C), as measured by rosette expressivity corresponding to the ratio of a transgenic line rosette area to that of the wild type. The penetrance, corresponding to the proportion of accessions showing an increased rosette area, was therefore 60%.

Figure 2.

Phenotype of GA20ox1 overexpressing (OE) lines of 17 Arabidopsis accessions. A, Image of 25-d-old rosettes of representative GA20ox1 OE lines and their corresponding wild type. Bar = 2 cm. B, Heat map representing, per accession, the average predicted percent difference in each leaf area between GA20ox1 OE lines and their corresponding wild type. Bold with underline: P value < 0.05. C, Heat map showing the estimated expressivity and penetrance (Sel, selective; Ros, rosette; see “Materials and Methods”) of GA20ox1 OE. D, GA levels in GA20ox1 OE lines. The normalized values represent the average concentrations between all transgenics for one accession and are represented with se bars (n = 3).

To test if the accessions show the same variation in response after exogenous treatment of GA, wild-type plants were grown in soil for 14 d and sprayed every 2 d with GA3, and at 25 d, individual leaf area was measured. As shown in Supplemental Figure S6 (Supplemental Table S7), we observed that accessions for which a large decrease in leaf area was found upon GA20ox1 overexpression (An-1, Ler-0, Blh1, and C24) also showed a decrease in leaf area upon GA3 treatment. Similarly, accessions for which transgenics showed the largest increase in leaf area (ICE61, ICE138, ICE97, or Oy-0) also presented an increase in leaf area when sprayed with GA3. For few accessions (WalhaesB4 or Col-0), the effect was different between the transgenics and the GA-treated plants. This discrepancy might be explained by the fact that the treatment started at 14 d, while GA20ox1 is overexpressed from the germination on.

In conclusion, we confirm that these accessions respond differently to changes in GA and that in the majority of the accessions the size of the young leaves is increased.

GA Levels

Next, we measured GA levels in the transgenic lines (Fig. 2E; Supplemental Fig. S7). We found that accumulation of GA20ox substrates GA53, GA44, GA19, and GA24 was reduced, whereas GA20ox products GA9 and GA20, two bioactive forms, as well as GA8, a bioinactive form of GA, were strongly increased in all transgenic accessions compared with their wild-type control. We noticed that, within each accession, the levels of GA1, and also of GA4, in the different transgenic lines were relatively constant. For example, similar high amounts of GA4 were found in the five transgenics from Ler-0, and this accumulation was 3-fold higher than the levels in the five transgenics from Blh-1. This constant level of accumulation suggests that the levels of these GAs are particularly well buffered within a given accession against different levels of GA20ox1 overexpression. However, there was no correlation between GA levels and expressivity of the growth-related phenotype (Supplemental Table S8), indicating that the downstream growth responses differ across accessions.

We also found that rosette expressivity was significantly positively correlated with leaf number and fresh and dry weight of the wild-type accessions and negatively correlated with both vascular complexity and density (Supplemental Fig. S8).

In conclusion, GA20ox1 overexpression causes distinct effects in different accessions, with the majority of accessions showing an enhanced leaf and rosette size.

Transcriptome Changes in Response to GA20ox1 Overexpression

We used RNA-seq of 10 accessions and their representative transgenic derivatives with variable changes in leaf 6 area to profile differential downstream responses of GA20ox1 overexpression. Because cell proliferation and/or cell expansion were affected in the transgenic lines (Fig. 2D) and the transition between cell proliferation and cell expansion is crucial for determining the final leaf size (Andriankaja et al., 2012; Gonzalez et al., 2012; Hepworth and Lenhard, 2014), leaves were microdissected (size <0.25 mm2) at the beginning of this transition, either at 12 or 13 DAS depending on the accession (see Methods), and used for RNA-seq. At this time point, only GA20ox1 and 2 were found to be expressed in the wild-type accessions with variable expression levels mainly for GA20ox2 between the accessions (Supplemental Fig. S9). Because these two genes are the major expressed forms of the GA20ox gene family in the accessions used for RNA-seq, we also verified the sequence of GA20ox2. As for GA20ox1, we found small changes between the accessions in the cDNA sequences that led to synonymous changes (Supplemental Fig. S10).

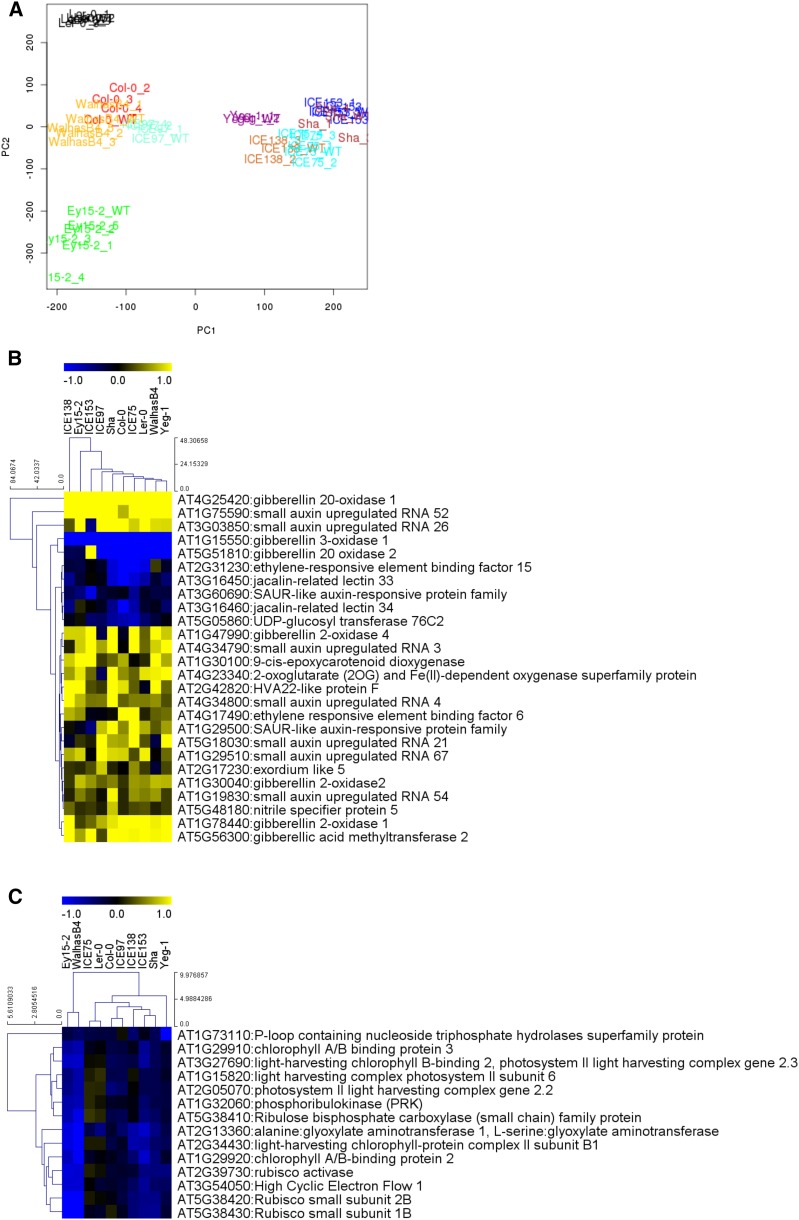

RNA-seq first confirmed overexpression of GA20ox1 in all transgenic lines (Supplemental Fig. S11), but this was not predictive of bioactive GA4 levels as measured by a nonsignificant Pearson correlation of 0.211. Consistent with the morphological observations, accession-specific properties dominated over the effects of GA20ox1 overexpression, as deduced from the principal component analysis (PCA; Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. S12).

Figure 3.

PCA of transcriptomics data and heat maps representing the fold change of differentially expressed genes in GA20ox1 OE lines. A, PCA plot representing classifications of transcriptomics data of wild-type and GA20ox1 OE lines. Each accession is displayed in a different color. W, wild type; 1-5, independent transgenic lines. B and C, Differentially expressed genes involved in hormone metabolism (B) and photosynthesis (C). Yellow and blue colors represent increased and decreased expression, respectively, in comparison with the wild types. Only DE genes that show at least 1.5-fold change difference are shown. Hierarchical clustering was done for both genes and samples with Manhattan distance metrics.

To identify differentially expressed genes, we considered transgenic lines of a particular accession as repeats of a single line because one sample per genotype was sequenced. Because only one wild-type sample per accession was sequenced, the experimental setup did not allow the identification of an accession-specific response. We therefore performed a statistical test to identify a general differential response between wild types and transgenic lines over the 10 accessions. A total of 730 genes were identified as differentially expressed (DE) with 361 with a fold change higher or lower than 1.5. Overrepresented Gene Ontology (GO) categories were photosynthesis, secondary metabolism, protein and hormone metabolism, regulation of transcription, transport, amino acid metabolism, and sulfur assimilation pathways (Fig. 3, B and C; Supplemental Table S9; Supplemental Fig. S13). Genes involved in GA deactivation and degradation (GIBBERELLIC ACID METHYLTRANSFERASE2, GA2ox1, and GA2ox4) were up-regulated, and GA biosynthetic genes GA3ox1 and GA20ox2 were down-regulated in many lines, indicative of feedback regulation (Fig. 3B). Several genes related to other phytohormones, including JA, ABA, brassinosteroid, auxin, ethylene, and cytokinin, were altered in expression, reflecting extensive cross-regulation among hormones (Weiss and Ori, 2007). For example, six small auxin up-regulated RNAs (SAUR), two ethylene response factors (ERF), and 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED), a gene encoding a rate-limiting enzyme in ABA biosynthesis, were differentially expressed in the GA20ox1 overexpression lines. Genes related to photosynthesis were mostly down-regulated (Fig. 3C). Because we analyzed young developing leaves, a possible explanation is that GA promotes growth and delays the onset of differentiation and the establishment of the photosynthetic apparatus by decreasing leaf chlorophyll content (Cheminant et al., 2011).

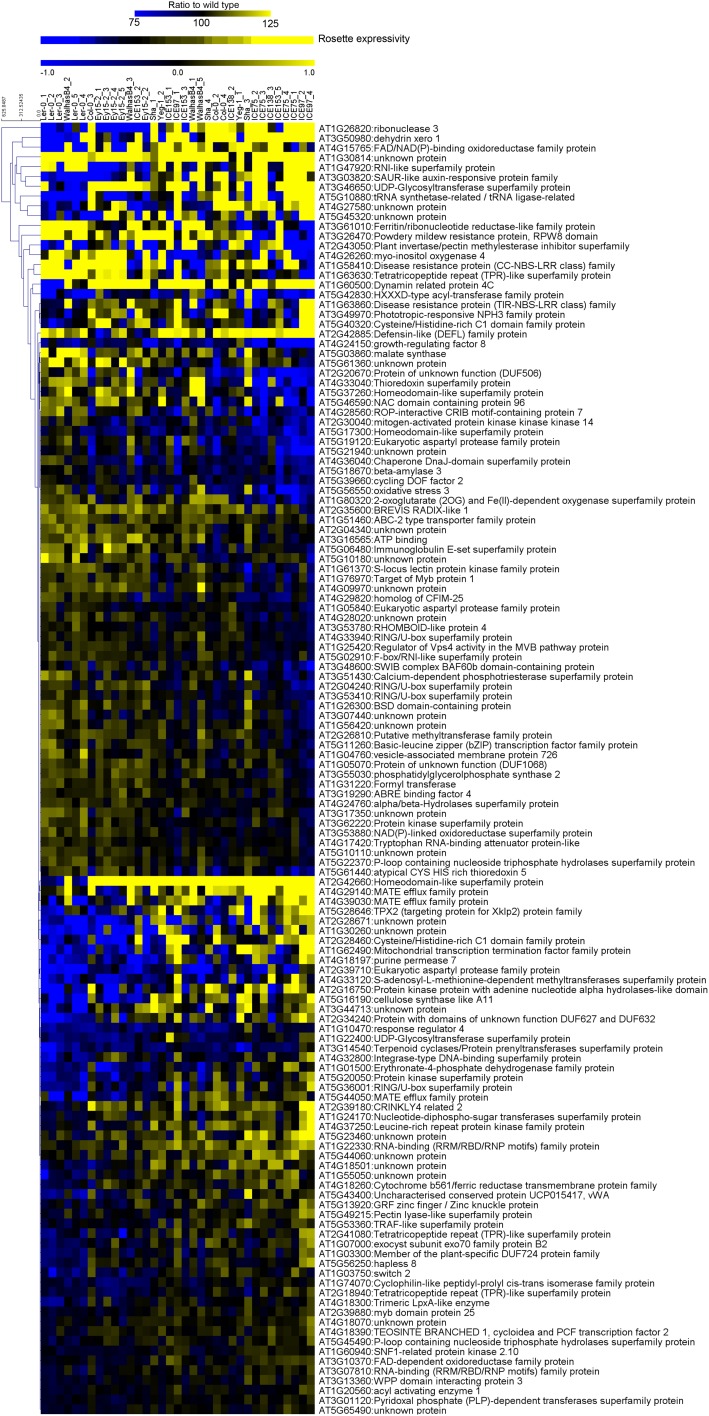

To identify genes for which the expression pattern could be linked to the degree of response to the transgenes, we estimated correlation between changes in expression and rosette expressivity. This correlation analysis identified 132 genes that were either significantly positively (71) or negatively (61) correlated with expressivity of morphological effects (Fig. 4). The genes with an expression positively correlating with rosette expressivity belonged to various GO categories, such as regulation of programmed cell death or regulation of response to drug or glycerol catabolic process, while the function of genes negatively correlated was related to circadian rhythm, response to organic stimulus, response to stress, and response to hormone, auxin, ethylene, and salicylic acid but also gibberellin (Supplemental Fig. S14). Among these genes, 13 were found to be significantly differentially expressed with a fold change higher or lower than 1.5.

Figure 4.

Correlation analysis between phenotypic and transcriptomic data. Heat maps represent the DE genes correlated with rosette expressivity and the expressivity of the rosette leaves. Yellow and blue correspond to increased and decreased expression, respectively, in comparison with the wild type. The DE genes with at least 1.5-fold change are indicated with an asterisk. Hierarchical clustering was done for genes with Manhattan distance metrics. Samples were ordered in function of the expressivity (correlation coefficient > |0.5|, adj-P value < 0.05).

We speculate that these genes (discussed below) might have important roles in determining the influence of GA20ox1 overexpression in the different accessions.

DISCUSSION

Overexpression of GA20ox1 in 17 accessions increased the levels of the bioactive forms of GA (GA1 and GA4) and depleted GA24, the direct precursor of GA4, in all accessions, demonstrating that the GA20ox1 transgene is active in all accessions. A remarkable observation was that the levels of GA1 and GA4 are very similar across multiple transgenic lines of an accession. In other words, there appears to be an accession-specific maximum accumulation level of GA1 and GA4. The reason for this is currently unclear, but it is known that bioactive GA forms stimulate the expression and activity of GA catabolism, counteracting the accumulation of the bioactive GAs and converting GA to bioinactive forms such GA8. Furthermore, GA represses the expression of endogenous genes encoding the GA biosynthetic genes GA20ox and GA3ox (Coles et al., 1999; Nelissen et al., 2012; Ribeiro et al., 2012). Such feedback regulation was also observed in the transcriptomics data of the GA20ox1 overexpression lines in all accessions analyzed. Possibly, there is an accession-specific feedback control in which the GA receptors and the GA-triggered degradation of DELLA proteins likely play a role (Ueguchi-Tanaka et al., 2007; Claeys et al., 2014). Although the majority of accessions showed a positive effect on leaf growth upon introduction of the GA20ox1 transgene, the effect quantitatively differed between accessions, and in some accessions, GA20ox1 overexpression had even a negative effect on leaf and rosette size. We confirmed this effect when wild-type plants were treated with GA3. However, no clear correlation could be found between the levels of GA20ox1 overexpression or the levels of various GAs and the observed effects. Similar genotype-dependent effects on freezing tolerance have been found when the cold tolerance genes CBF1, CBF2, and CBF3 were down-regulated in eight different accessions of Arabidopsis (Gery et al., 2011).

We also observed that the biomass of the wild-type accessions was positively correlated with the growth-promoting effect of GA20ox1 overexpression on rosette size. Accessions with larger rosettes showed a more pronounced response to GA20ox1 overexpression than those with smaller rosettes. We hypothesize that in large accessions, the growth-regulatory network is less constrained and more prone to the effect of positive growth regulators, whereas in small accessions, which have a more restrictive growth network, it would be more difficult to make larger plants. In addition, it seems that there is more room for physical expansion in larger accessions because vascular density and complexity in the wild-type accessions showed a negative correlation with rosette expressivity. For rosette expressivity, no direct correlation with GA levels was found. A possible reason for this observation is that rosette size is a complex trait determined by many different factors, among which leaf number and size and speed of development that therefore has to integrate different individual organs.

How can we explain the natural variation in the effect of GA20ox1 overexpression based on our finding of almost no strong correlation between its transcript level, active GA quantities, and phenotypic effects? Because many steps exist between the expression of GA20ox1 and its actual effect on growth, differences in signal transduction along the GA pathway, depending on the genetic background, could therefore be the reason for the observed variability. First, translatome analysis after treatment with bioactive GAs has revealed that differential mRNA translation, possibly varying between the different accessions, is important for the control of feedback regulation of GA-related genes (Ribeiro et al., 2012). Second, at the protein level, the amount of the GA-receptor (GID) and DELLAs, which are negative regulators of GA signaling, their affinity, and their efficiency to form the regulatory module GA-GID-DELLA might be different in the different accessions and, therefore, differentially affect the response. Distinct interactions with other growth regulatory elements could also explain the variation observed. It has been shown, in Col-0, that overexpression of GA20ox1 in binary combination with an altered expression of growth-promoting genes leads to different size phenotypes in function of the gene combination (Vanhaeren et al., 2014). It is therefore possible that differences in expression of growth regulatory genes, triggering different cellular characteristics in the wild-type plants, differently influence the effect of GA20ox1 overexpression. In addition, we identified 132 genes of which the expression levels are correlated with the phenotypic expressivity of GA20ox1 in all analyzed accessions. Interestingly, among the genes having an expression pattern negatively correlated with the degree of response to GA20ox1, several are related to the response to hormone stimulus and especially to GA. For example, XERICO (AT2G04240), known to be up-regulated by DELLA and repressed by GA and to promote accumulation of ABA (Zentella et al., 2007), is more or less expressed in the accessions presenting the smallest or largest rosette expressivity, respectively. In addition, few of the correlated genes have previously been associated with plant growth. For example, GRF8 (AT4G24150) is one of the nine members of the GROWTH REGULATING FACTOR gene family with a major role in regulating cell proliferation and/or cell expansion during plant development (Kim et al., 2003; Vercruyssen et al., 2014). Two auxin-related genes were also found to correlate with rosette expressivity: ARABIDOPSIS ABNORMAL SHOOT3 (AT4G29140; Li et al., 2014) and REVEILLE1 (AT5G17300; Rawat et al., 2009). Interestingly, it has been shown that REVEILLE1 binds to the promoter of GIBBERELLIN 3-OXIDASE2, can inhibit its transcription, and therefore suppresses the biosynthesis of GA (Jiang et al., 2016). Further work is required to determine whether this subset of genes has, either alone or in combination, a functional role in determining the accession-specific responses to elevated GA levels.

CONCLUSION

Plant growth is regulated by complex molecular networks that are determined by the genome and its interaction with the ever-changing environment. Such growth regulatory networks are expected to be rather different among species and even within a species, which might serve as a key element in adaptation to different environments. It has been demonstrated that mutations or transgenes influencing growth might have different effects in different genetic backgrounds in several model organisms (Dowell et al., 2010; Chandler et al., 2013). Here, we show for 17 different Arabidopsis accessions that the ectopic expression of a rate-limiting enzyme for gibberellin biosynthesis has very different effects on growth depending on the accession in which the gene is introduced. Most accessions visibly responded by changing their growth especially with an altered leaf size and shape. However, across the accessions, the response did not always correspond to a positive effect on growth. Ten accessions showed larger rosettes whereas others had smaller rosette size compared to the wild type. We observed that in all transgenic lines, GA levels showed the same direction of accumulation, suggesting that GA biosynthesis/metabolism pathway is commonly changed across the accessions. Remarkably, transcript levels of GA20ox1 did not correlate with the levels of bioactive GA. Furthermore, the levels of bioactive GA forms in the different transgenic lines were remarkably constant for all transgenics in each accession, suggesting the existence of an accession-specific plateau for maximal accumulation of these GAs. GA levels were therefore not correlated with the phenotypes, suggesting that a high accumulation level of GA is not always responsible for a positive growth regulation.

In order to provide further insight into the mechanism that is behind the accession-specific effect of GA perturbation, screening for modifier genes that suppress the response to GA perturbation in transgenic lines of a specific accession could be performed. Furthermore, detailed analysis of the GA signaling pathway in the different accessions is likely to shed light on how GA affects growth to a very different extent in different Arabidopsis accessions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Seventeen Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) accessions were selected to cover most common genetic variants of Arabidopsis (Supplemental Table S1) and used to generate GA20ox1-overexpressing lines. cDNA of the full GA20ox1 coding region from Col-0 was cloned in the fluorescence-accumulating seed technology vectors (Shimada et al., 2010) and introduced into the 17 accessions following the floral dip protocol (Clough and Bent, 1998). Dried transgenic T1 seeds were selected based on fluorescence signal in the seed coat and sown on soil for seed production. T2 transgenic seeds were harvested, and selection of five independent single-locus insertion lines (75% of fluorescent seeds) was done. Seeds were sown on soil for seed production, and expression of the transgene was verified by RT-qPCR. From these lines, at least two and maximum five independent T3 homozygote lines for each accession were selected for further experiments. All plants were grown in soil under a 16-h-day/8-h-night regime at 21°C in a growth chamber.

For GA treatments, the 17 accessions were grown in soil until 14 d after stratification, and plants were sprayed every second day with 1 mL of 50 μm GA3 containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 80 or mock (Ribeiro et al., 2012). Leaf series were made when plants were 25 d old.

Phenotypic Analysis

Measurement of 13 Leaf Size-Related Parameters in 17 Accessions

Twenty four plants for each accession were grown in soil for 25 d in three independent experiments. Plants were randomly distributed. Fresh and dry weight was measured from 8 to 12 plants, and leaf series were made by dissecting individual leaves from 8 to 12 plants and mounting them on a 1% agar plate. The area of each individual leaf was measured with the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Total rosette area and total leaf number were calculated from the leaf series analysis. Measurements of venation patterns were done as previously described (Dhondt et al., 2012) from leaves 1 and 2. The cellular analysis on leaves 1 and 2 was done as previously described (Andriankaja et al., 2012) and allowed calculating pavement cell number, area, and circularity and stomatal index and density. Ploidy levels of leaves 1 and 2 were measured, and the endoreduplication index was calculated as previously described (Claeys et al., 2012). The measurements of fresh and dry weight, total leaf number, leaves 1 and 2, total rosette area, and endoreduplication index were obtained from the three repeats. The cellular analysis and the vasculature analysis were done for two repeats from five leaves for each repeat. For the heat map of leaf size-related parameters (total rosette area, fresh weight and dry weight of the shoot, total number and area of leaves, pavement cell number and area, cell circularity, endoreduplication index, stomatal density, stomatal index, and vascular complexity and density of leaves 1 and 2) in the 17 accessions, the measured value for a parameter in each accession was divided by the average of this parameter for all accessions.

Measurement of Leaf Area in the Transgenic Lines

Ten plants per genotype were grown in a randomized manner for 25 d in soil. All the independent transgenics for an accession were grown in the same experiment together with their corresponding wild type. Separate experiments for each natural accession were conducted. Leaf series were made by dissecting individual leaves from 10 plants, and the leaf area was measured with the ImageJ software.

To evaluate the response to the transgene and therefore to estimate the effect of the transgene in the background of the natural accession versus the untransformed natural accession on each leaf, leaf area was log transformed to stabilize the variance. Data were truncated so that there were at least two observations for each leaf of both the transgenic lines and the corresponding wild type. The mean model consisted of the main effects of GA20ox1 overexpression on leaf size and their interaction term. Due to the unbalanced and complex nature of the data, the Kenward-Rogers approximation for computing the denominator degrees of freedom for the tests of fixed effects was used. An autoregressive structure was used to model the correlations between measurements done on the leaves originating from the same plant. The main interest was in the effect of the gene on leaf area for each leaf separately. Simple tests of effects were performed at each leaf between the transgenic lines and the corresponding wild type. Difference estimates were represented as percentage of the least-square means estimate of the wild type and leaf. The analysis was performed with the mixed and plm procedure of SAS (version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows 7, 64 bit; SAS Institute).

Rosette expressivity is defined as the ratio of a transgenic line rosette area to that of the wild type. In the case of rosette expressivity per accession, the mean of rosette expressivity per transgenic line for an accession has been taken.

Hormone Analysis

The shoot of seedlings grown in soil until stage 1.03 (Boyes et al., 2001; 12 DAS for Cvi-0 and 11 DAS for the other accessions) was harvested in the middle of the day for three independent experiments and frozen in liquid nitrogen. The phytohormones GA (GA4, GA8, GA9, GA19, GA24, GA44, and GA53), IAA (IAA, IAAsp, IAIle + IALeu, and IAPhe), ABA, SA, cytokinin (tZ, tZR, tZRPs, cZ, cZR, cZRPs, DZ, DZR, DZRPs, iP, iPR, iPRPs, tZ7G, tZ9G, tZOG, tZROG, cZROG, tZRPsOG, DZ9G, iP7G, and iP9G), and JA were measured as described previously (Kojima et al., 2009; Shinozaki et al., 2015). The hormone data were modeled with a linear model with accession as main factor and experiment as fixed block factor due to small number of samples (three repeats). The model was fitted with the lm function from the R software (v 3.0.1; R Core Team, 2015). Least squares means and standard errors were calculated with the lsmeans function of the lsmeans library (v. 2.10; Lenth and Hervé, 2014) from the R software (v 3.0.1; R Core Team, 2015). These estimates were used in Pearson correlation analyses.

RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from the shoot of 12-d-old seedlings of T2 transgenic lines and the corresponding wild-type plants according to a combined protocol of TRIzol (Invitrogen) and the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase (Qiagen) digestion. The expression of the transgene was analyzed by RT-qPCR. RT-qPCR was performed as previously described (Claeys et al., 2012).

For RNA-seq analysis, seedlings with one biological repeat of wild-type plants and GA20ox1-overexpressing lines (at 12 DAS for Col-0 and Ey15-2 and at 13 DAS for WalhaesB4, ICE97, ICE138, ICE75, Ler-0, Yeg-1, Sha, and ICE153) were harvested in RNA ice-later solution (AM7030; Ambion) and incubated at −20°C for at least a week. Leaf 6 was microdissected on a cold plate with dry ice under a stereomicroscope and frozen in liquid nitrogen. RNA was extracted according to a combined protocol of TRIzol (Invitrogen) and the RNeasy kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase (Qiagen) digestion. RNA was quantified and the quality was checked with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent).

RNA-Seq Analysis

Library preparation was done using the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit v2 (Illumina). In brief, poly(A)-containing mRNA molecules were reverse transcribed, double-stranded cDNA was generated, and adapters were ligated. After quality control using the 2100 Bioanalyzer, clusters were generated through amplification using the TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS kit (Illumina) followed by sequencing on a Illumina HiSeq 2000 with the TruSeq SBS Kit v3-HS (Illumina). Sequencing was performed in paired-end mode with a read length of 50 bp. The quality of the raw data was verified with FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/; version 0.9.1). Next, quality filtering was performed using the FASTX toolkit (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/; version 0.0.13): Reads where globally filtered in which for at least 75% of the reads the quality exceeds Q20, and 3′ trimming was performed to remove bases with a quality below Q10. Repairing was performed using a custom Perl script. Reads were subsequently mapped to the Arabidopsis reference genome (TAIR10) using GSNAP (Wu and Nacu, 2010; version 2011-12-28) allowing maximally two mismatches. The concordantly paired reads that uniquely map to the genome were used for quantification on the gene level with htseq-count from the HTSeq.py python package (Anders et al., 2015). The analysis was implemented as a workflow in Galaxy (Goecks et al., 2010).

For the visualization of RNA-seq expression data and correlation analysis, count data were normalized following the normalization pipeline with the trimmed mean of M-values algorithm as implemented in the edgeR library from the R software (v.3.0.1; R Core Team, 2015). Weakly expressed genes were previously filtered out by removing genes that have less than five samples with an expression level lower than 0.5 counts per million. The 0 counts of normalized data were substituted with value 1-e10 and then the whole data set was log2 transformed.

The PCA plot on transformed count data were done in R software (v.3.0.1; R Core Team, 2015) using the “prcomp” function.

Differential Expression Analysis

Differential expression analyses of RNA-seq data were conducted with the EdgeR library (v.3.4.2) of the Bioconductor software from the R software (v.3.0.1; R Core Team, 2015). Filtering and normalization were performed as previously described. In this analysis, we consider transgenic lines of a particular accession as repeats of a single line; otherwise, we would not be able to run statistical tests because we have a single repeat per line. A statistical test for general, mean differential expression between wild types of accessions and transgenic lines of these accessions was performed using the glmLRT function with a contrast (Accession1_WT – Accession1_OE) + Accession2_WT – Accession1_OE) +…. + (AccessionN_WT – AccessionN_OE). For further analysis, genes were selected based on their false discovery rate adjusted P value lower than 0.05 and/or fold change threshold between transgenic lines and the wild type. The filter on the fold change requires a fold change higher than 1.5 for each transgenic line of an accession in at least one accession.

Enrichment analysis was done in MapMan (Ramšak et al., 2014; http://mapman.gabipd.org/) with significantly DE genes.

Heat maps are generated in Mev (v 4.9; Howe et al., 2011) for significantly DE genes filtered for and a 1.5-fold change threshold between transgenic lines and the wild type. Hierarchical clustering was done for both genes and samples with Manhattan distance metrics in Mev (v 4.9; Howe et al., 2011).

Sequence Extraction and Alignment

The sequences from AT4G25420 and AT5G51810 were extracted from the RNA-seq data. After preprocessing and mapping of the reads to the TAIR10 genome, sorting and deduplication of the read libraries were performed using picard v1.129 (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). GATK v3.3.0 was used for variant calling (Van der Auwera et al., 2013). Analysis was based on recommendations in “Best Practices for RNA-seq” (https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/guide/best-practices?bpm=RNAseq). Before variant calling was performed, the different libraries were preprocessed using the tools splitnCigar, haplotypecaller, realignertargetcreator, indelrealigner, baserecalibrator, and printreads. In the haplotypecaller step, only high-quality scores were considered by setting a quality of 50. Next, a multisample variant calling was performed using haplotypecaller. In this step, all samples are analyzed together. Variants were filtered using VariantFiltration with the options -window 35, -cluster 3, -filterName FS, -filter “FS > 30.0”, -filterName QD, and -filter “QD < 2.0.” The resulting variants file was split by sample using bcftools (http://github.com/samtools/bcftools). Sequences were extracted for the genes (AT4G25420 and AT5G51810) using the alternative alleles for each sample using the GATK tool Fasta Alternate Reference Maker (Van der Auwera et al., 2013) and based on the Coding DNA Sequence coordinates (based on the structural annotation of TAIR10). The reverse complement was generated for genes located at the negative strand and subsequently protein sequences were extracted using custom scripts.

To align the extracted sequences, CLC main Workbench 6.0 was used (CLC bio, a Qiagen Company).

Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation coefficient tests were run independently between phenotypes, between phenotypes and hormones, between hormones, and between penetrance and RNA-seq fold change data. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated with corr.test function in R. The adjusted P values of correlations were calculated with a permutation test. We permuted a tested trait and ran correlation tests over the whole considered data set. Such a run was repeated 1000 times. The adjusted P values are calculated from all runs over all repeats as a proportion of correlation coefficients correlated in a higher degree than a tested correlation (r) to the number of permuted correlations (n), with a formula (r + 1)/(n + 1) (North et al., 2002). The significant correlations, false discovery rate < 0.05, were visualized in Cytoscape (Cline et al., 2007).

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Correlation between the shoot-related phenotypic measurements of the 17 Arabidopsis accessions.

Supplemental Figure S2. Correlation between four of the major bioactive hormones (ABA, cytokinin, JA, and ABA) in 17 Arabidopsis accessions.

Supplemental Figure S3. Correlation between the leaf size-related parameters and hormones in the 17 Arabidopsis accessions.

Supplemental Figure S4. Sequence alignments of GA20ox1 cDNA and the corresponding protein from 16 of the 17 Arabidopsis accessions studied.

Supplemental Figure S5. Heat map representing, per accession, the predicted percent difference in each leaf area between each independent GA20ox1 OE lines and their corresponding wild type.

Supplemental Figure S6. Heat map representing, per accession, the percentage of difference in each leaf area between plants sprayed with GA3 (GA) and the control plants (mock).

Supplemental Figure S7. GA levels in GA20ox1 OE lines from the 17 Arabidopsis accessions.

Supplemental Figure S8. Correlation analysis of phenotypic data.

Supplemental Figure S9. GA20ox1 and GA20ox2 expression levels in the 10 Arabidopsis accessions used for RNA-seq.

Supplemental Figure S10. Sequence alignments of GA20ox2 cDNA and the corresponding protein from 10 of the 17 Arabidopsis accessions studied.

Supplemental Figure S11. GA20ox1 expression level in the transgenic lines from 10 Arabidopsis accessions.

Supplemental Figure S12. Variance explained by first 20 components for the RNA-seq analysis from the 10 accessions.

Supplemental Figure S13. Heat maps representing the fold change of DE genes in GA20ox1 OE lines.

Supplemental Figure S14. Overrepresented GO categories (biological process) for genes positively and negatively correlated with rosette expressivity.

Supplemental Table S1. Geographic origin of the 17 Arabidopsis accessions used in this study.

Supplemental Table S2. Measurements of 13 leaf size-related parameters in 17 accessions.

Supplemental Table S3. Correlation between levels of different hormones in the 17 Arabidopsis accessions.

Supplemental Table S4. Percentage differences between the sequences of GA20ox1 in 15 accessions and Col-0 at DNA and protein level.

Supplemental Table S5. Average individual leaf area (cot = cotyledon; L1 to L21 = leaf 1 to leaf 21) in the independent GA20ox1 overexpressing lines (E1 to E5) and their respective wild-type accessions.

Supplemental Table S6. Average values given as least square means predicted according to the statistical models and variation.

Supplemental Table S7. Average leaf area values given as least square means predicted according to the statistical models and variation.

Supplemental Table S8. Pearson correlation between the rosette expressivity after GA20ox1 overexpression and GA levels in the transgenics.

Supplemental Table S9. Overrepresented MapMan categories for GA20ox1 DE genes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Systems Biology of Yield group for help with experiments and many discussions. We also thank Dr. Annick Bleys and Dr. Bram Slabbinck for help in improving the article.

Glossary

- GA

gibberellin

- DAS

days after stratification

- SA

salicylic acid

- JA

jasmonic acid

- ABA

abscisic acid

- IAA

indole-3-acetic acid

- PCA

principal component analysis

- DE

differentially expressed

- GO

Gene Ontology

Footnotes

This research received funding from the Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds Methusalem Project (BOF08/01M00408). Work at the Max Planck Institute is supported by ERC Advanced Grant IMMUNEMESIS and the Max Planck Society.

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W (2015) HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31: 166–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriankaja M, Dhondt S, De Bodt S, Vanhaeren H, Coppens F, De Milde L, Mühlenbock P, Skirycz A, Gonzalez N, Beemster GTS, Inzé D (2012) Exit from proliferation during leaf development in Arabidopsis thaliana: a not-so-gradual process. Dev Cell 22: 64–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes DC, Zayed AM, Ascenzi R, McCaskill AJ, Hoffman NE, Davis KR, Görlach J (2001) Growth stage-based phenotypic analysis of Arabidopsis: a model for high throughput functional genomics in plants. Plant Cell 13: 1499–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler CH, Chari S, Dworkin I (2013) Does your gene need a background check? How genetic background impacts the analysis of mutations, genes, and evolution. Trends Genet 29: 358–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chari S, Dworkin I (2013) The conditional nature of genetic interactions: the consequences of wild-type backgrounds on mutational interactions in a genome-wide modifier screen. PLoS Genet 9: e1003661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheminant S, Wild M, Bouvier F, Pelletier S, Renou J-P, Erhardt M, Hayes S, Terry MJ, Genschik P, Achard P (2011) DELLAs regulate chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis to prevent photooxidative damage during seedling deetiolation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 23: 1849–1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys H, De Bodt S, Inzé D (2014) Gibberellins and DELLAs: central nodes in growth regulatory networks. Trends Plant Sci 19: 231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claeys H, Skirycz A, Maleux K, Inzé D (2012) DELLA signaling mediates stress-induced cell differentiation in Arabidopsis leaves through modulation of anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome activity. Plant Physiol 159: 739–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline MS, Smoot M, Cerami E, Kuchinsky A, Landys N, Workman C, Christmas R, Avila-Campilo I, Creech M, Gross B, et al. (2007) Integration of biological networks and gene expression data using Cytoscape. Nat Protoc 2: 2366–2382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles JP, Phillips AL, Croker SJ, García-Lepe R, Lewis MJ, Hedden P (1999) Modification of gibberellin production and plant development in Arabidopsis by sense and antisense expression of gibberellin 20-oxidase genes. Plant J 17: 547–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruyne L, Höfte M, De Vleesschauwer D (2014) Connecting growth and defense: the emerging roles of brassinosteroids and gibberellins in plant innate immunity. Mol Plant 7: 943–959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhondt S, Van Haerenborgh D, Van Cauwenbergh C, Merks RMH, Philips W, Beemster GTS, Inzé D (2012) Quantitative analysis of venation patterns of Arabidopsis leaves by supervised image analysis. Plant J 69: 553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell RD, Ryan O, Jansen A, Cheung D, Agarwala S, Danford T, Bernstein DA, Rolfe PA, Heisler LE, Chin B, et al. (2010) Genotype to phenotype: a complex problem. Science 328: 469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Félix M-A. (2007) Cryptic quantitative evolution of the vulva intercellular signaling network in Caenorhabditis. Curr Biol 17: 103–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Félix M-A, Wagner A (2008) Robustness and evolution: concepts, insights and challenges from a developmental model system. Heredity (Edinb) 100: 132–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gery C, Zuther E, Schulz E, Legoupi J, Chauveau A, McKhann H, Hincha DK, Téoulé E (2011) Natural variation in the freezing tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana: effects of RNAi-induced CBF depletion and QTL localisation vary among accessions. Plant Sci 180: 12–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J; Galaxy Team (2010) Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol 11: R86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez N, De Bodt S, Sulpice R, Jikumaru Y, Chae E, Dhondt S, Van Daele T, De Milde L, Weigel D, Kamiya Y, et al. (2010) Increased leaf size: different means to an end. Plant Physiol 153: 1261–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez N, Vanhaeren H, Inzé D (2012) Leaf size control: complex coordination of cell division and expansion. Trends Plant Sci 17: 332–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P. (2003) The genes of the Green Revolution. Trends Genet 19: 5–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Thomas SG (2012) Gibberellin biosynthesis and its regulation. Biochem J 444: 11–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth J, Lenhard M (2014) Regulation of plant lateral-organ growth by modulating cell number and size. Curr Opin Plant Biol 17: 36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe EA, Sinha R, Schlauch D, Quackenbush J (2011) RNA-Seq analysis in MeV. Bioinformatics 27: 3209–3210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Raman AS, Ream JE, Fujiwara H, Cerny RE, Brown SM (1998) Overexpression of 20-oxidase confers a gibberellin-overproduction phenotype in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 118: 773–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Xu G, Jing Y, Tang W, Lin R (2016) Phytochrome B and REVEILLE1/2-mediated signalling controls seed dormancy and germination in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun 7: 12377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Choi D, Kende H (2003) The AtGRF family of putative transcription factors is involved in leaf and cotyledon growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J 36: 94–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M, Kamada-Nobusada T, Komatsu H, Takei K, Kuroha T, Mizutani M, Ashikari M, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Matsuoka M, Suzuki K, Sakakibara H (2009) Highly sensitive and high-throughput analysis of plant hormones using MS-probe modification and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: an application for hormone profiling in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol 50: 1201–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth RV, Hervé M (2014) lsmeans: Least-Squares Means. R package version 2.13, https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lsmeans/index.html

- Li R, Li J, Li S, Qin G, Novák O, Pěnčík A, Ljung K, Aoyama T, Liu J, Murphy A, et al. (2014) ADP1 affects plant architecture by regulating local auxin biosynthesis. PLoS Genet 10: e1003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen H, Rymen B, Jikumaru Y, Demuynck K, Van Lijsebettens M, Kamiya Y, Inzé D, Beemster GTS (2012) A local maximum in gibberellin levels regulates maize leaf growth by spatial control of cell division. Curr Biol 22: 1183–1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North BV, Curtis D, Sham PC (2002) A note on the calculation of empirical P values from Monte Carlo procedures. Am J Hum Genet 71: 439–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paaby AB, White AG, Riccardi DD, Gunsalus KC, Piano F, Rockman MV (2015) Wild worm embryogenesis harbors ubiquitous polygenic modifier variation. eLife 4: e09178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plackett ARG, Powers SJ, Fernandez-Garcia N, Urbanova T, Takebayashi Y, Seo M, Jikumaru Y, Benlloch R, Nilsson O, Ruiz-Rivero O, et al. (2012) Analysis of the developmental roles of the Arabidopsis gibberellin 20-oxidases demonstrates that GA20ox1,-2, and -3 are the dominant paralogs. Plant Cell 24: 941–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramšak Ž, Baebler Š, Rotter A, Korbar M, Mozetič I, Usadel B, Gruden K (2014) GoMapMan: integration, consolidation and visualization of plant gene annotations within the MapMan ontology. Nucleic Acids Res 42: D1167–D1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat R, Schwartz J, Jones MA, Sairanen I, Cheng Y, Andersson CR, Zhao Y, Ljung K, Harmer SL (2009) REVEILLE1, a Myb-like transcription factor, integrates the circadian clock and auxin pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 16883–16888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2015) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

- Ribeiro DM, Araújo WL, Fernie AR, Schippers JH, Mueller-Roeber B (2012) Translatome and metabolome effects triggered by gibberellins during rosette growth in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 63: 2769–2786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieu I, Ruiz-Rivero O, Fernandez-Garcia N, Griffiths J, Powers SJ, Gong F, Linhartova T, Eriksson S, Nilsson O, Thomas SG, et al. (2008) The gibberellin biosynthetic genes AtGA20ox1 and AtGA20ox2 act, partially redundantly, to promote growth and development throughout the Arabidopsis life cycle. Plant J 53: 488–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilsky RL. (2010) Personalized medicine in oncology: the future is now. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9: 363–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwechheimer C, Willige BC (2009) Shedding light on gibberellic acid signalling. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 57–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada TL, Shimada T, Hara-Nishimura I (2010) A rapid and non-destructive screenable marker, FAST, for identifying transformed seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 61: 519–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki Y, Hao S, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Ozeki-Iida Y, Zheng Y, Fei Z, Zhong S, Giovannoni JJ, Rose JKC, et al. (2015) Ethylene suppresses tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit set through modification of gibberellin metabolism. Plant J 83: 237–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Nakajima M, Motoyuki A, Matsuoka M (2007) Gibberellin receptor and its role in gibberellin signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 58: 183–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Chris Hartl C, Poplin R, del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, Jordan T, Shakir K, Roazen D, Thibault J, et al. (2013) From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 11: 11.10.1–11.10.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhaeren H, Gonzalez N, Coppens F, De Milde L, Van Daele T, Vermeersch M, Eloy NB, Storme V, Inzé D (2014) Combining growth-promoting genes leads to positive epistasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. eLife 3: e02252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercruyssen L, Verkest A, Gonzalez N, Heyndrickx KS, Eeckhout D, Han S-K, Jégu T, Archacki R, Van Leene J, Andriankaja M, et al. (2014) ANGUSTIFOLIA3 binds to SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes to regulate transcription during Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant Cell 26: 210–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu V, Verster AJ, Schertzberg M, Chuluunbaatar T, Spensley M, Pajkic D, Hart GT, Moffat J, Fraser AG (2015) Natural variation in gene expression modulates the severity of mutant phenotypes. Cell 162: 391–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, Ori N (2007) Mechanisms of cross talk between gibberellin and other hormones. Plant Physiol 144: 1240–1246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TD, Nacu S (2010) Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics 26: 873–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentella R, Zhang ZL, Park M, Thomas SG, Endo A, Murase K, Fleet CM, Jikumaru Y, Nambara E, Kamiya Y, Sun TP (2007) Global analysis of della direct targets in early gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 3037–3057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]