Abstract

Unhealthy alcohol use is the third leading cause of preventable death in the United States (U.S.). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for unhealthy alcohol use but little is known about how best to do so. We used quality improvement techniques to implement a systematic approach to screening and counseling primary care patients for unhealthy alcohol use. Components included use of validated screening and assessment instruments; an evidence-based 2-visit counseling intervention using motivational interviewing techniques for those with risky drinking behaviors who did not have an alcohol use disorder (AUD); shared decision making about treatment options for those with an AUD; support materials for providers and patients; and training in motivational interviewing for faculty and residents. Over the course of one year, we screened 52% (N=5,352) of our clinic’s patients and identified 294 with positive screens. Of those 294, appropriate screening-related assessments and interventions were documented for 168 and 72 patients, respectively. Although we successfully implemented a systematic screening program and structured processes of care, ongoing quality improvement efforts are needed to screen the rest of our patients and to improve the consistency with which we provide and document appropriate interventions.

Keywords: Unhealthy Alcohol Use, Binge Drinking/prevention & control, Counseling, Screening, Primary Health Care

INTRODUCTION

Unhealthy alcohol use is the third leading cause of preventable death in the United States (U.S.). (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013b; Saitz, 2005) Terminology related to unhealthy alcohol use is complex and overlapping; it includes risky drinking and alcohol use disorder (AUD). We provide definitions in Table 1. Unhealthy alcohol use is associated with numerous health and societal problems and is responsible for 10% of deaths among working-age adults in the U.S. (Bondy, Rehm, Ashley, Walsh, Single, & Room, 1999; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004; Cherpitel & Ye, 2008; Corrao, Bagnardi, Zambon, & La Vecchia, 2004; Jonas, Garbutt, Amick, Brown, Brownley, Council et al., 2012a; Rehm, Baliunas, Borges, Graham, Irving, Kehoe et al., 2010; Schuckit, 2009; Shalala & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000; Stahre, Roeber, Kanny, Brewer, & Zhang, 2014) Over 20% of primary care patients in the U.S. exceed maximum recommended limits (Vinson, Manning, Galliher, Dickinson, Pace, & Turner, 2010) (Table 1), and those in the uppermost decile for alcohol consume an average of 74 drinks per week. (Cook, 2007; Ingraham, September 25, 2014)

Table 1.

Definitions of unhealthy alcohol use (i.e., alcohol misuse), risky use, and alcohol use disorder

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Unhealthy alcohol use(Jonas et al., May 2014; Jonas et al., 2012) (i.e., alcohol misuse) | Overarching term that includes risky drinking and alcohol use disorder. |

| Risky use(Jonas et al., May 2014; Jonas et al., 2012) (i.e., hazardous use) |

Consumption levels that increase the risk for health consequences. Consumption of alcohol above recommended daily, weekly, or per-occasion amounts. Maximum recommended thresholds for daily or weekly amounts:(Updated 2005 Edition)

|

| Alcohol use disorder† (DSM-5, 2013(American Psychiatric Association, 2013)); levels of severity—mild: 2-3 criteria; moderate: 4-5 criteria; severe: ≥6 criteria |

|

A standard drink is 12 ounces (1 can) of beer containing 5% alcohol, 5 ounces of wine containing 12% alcohol, or 1.5 ounces of hard liquor containing 40% alcohol (80 proof). Many microbrews have a higher alcohol content; 12 ounces is often 1.5 drinks. (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Updated 2005 Edition)

Unlike DSM-III and DSM–IV, DSM-5 (2013) describes a single alcohol use disorder category measured on a continuum from mild to severe, and no longer has separate categories for alcohol abuse and dependence. Diagnosis of alcohol use disorder requires at least 2 of the 11 criteria listed.

Systematic reviews have shown benefits of screening and counseling. (Jonas et al., 2012a; Jonas, Garbutt, Brown, Amick, Brownley, Council et al., 2012b) The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening adults for unhealthy alcohol use and providing persons engaged in risky drinking with brief behavioral counseling; (Moyer & Preventive Services Task Force, 2013) people found to have AUD should receive more intensive interventions. Yet, less than a third of those who visit general medical providers are asked about alcohol use, and less than 20% of U.S. adults report ever discussing alcohol use with a health professional. (D'Amico, Paddock, Burnam, & Kung, 2005; McKnight-Eily, Liu, Brewer, Kanny, Lu, Denny et al., 2014) Further, primary care residents have been shown to lack comfort and experience with alcohol screening and brief intervention. (Le, Johnson, Seale, Woodall, Clark, Parish et al., 2015) Barriers to screening and counseling include competing priorities, lack of provider training, misconceptions about patient comfort with discussing alcohol, and lack of appropriate infrastructure and protocols. To address these shortcomings, we sought to develop and implement, using quality improvement techniques, a systematic approach to screening and counseling primary care patients for unhealthy alcohol use.

IMPLEMENTATION AND QUALITY IMPROVEMENT METHODS

Setting and Participants

The University of North Carolina Internal Medicine Clinic (UNC IMC) is a large academic practice serving 12,300 adults with approximately 42,000 visits per year. It is recognized as a Level 3 Patient-Centered Medical Home and has over a 15-year history of conducting formal quality improvement activities. (Cavanaugh, Jones, Embree, Tsai, Miller, Shilliday et al., 2014; DeWalt, Malone, Bryant, Kosnar, Corr, Rothman et al., 2006; Jonas, Bryant Shilliday, Laundon, & Pignone, 2010; Jonas, Evans, McLeod, Brode, Lange, Young et al., 2013; Kiser, Jonas, Warner, Scanlon, Shilliday, & DeWalt, 2012; Potisek, Malone, Shilliday, Ives, Chelminski, DeWalt et al., 2007; Rothman, DeWalt, Malone, Bryant, Shintani, Crigler et al., 2004; Rothman, Malone, Bryant, Shintani, Crigler, Dewalt et al., 2005; Rothman, So, Shin, Malone, Bryant, Dewalt et al., 2006) Prior to implementation of this screening program for unhealthy alcohol use, our practice did not routinely screen patients for unhealthy alcohol use. When we initially developed and implemented our program, UNC used a home-grown electronic health record. UNC IMC employed a visit-based, computer-generated, paper-based, prioritized screening and prevention prompting system for a variety of general health issues. An algorithm generated distinct front desk, nursing, and physician prompts for up to 3 health issues that were relevant for each patient from a prioritized list of 16 possible items (Appendix 1).

Program Description

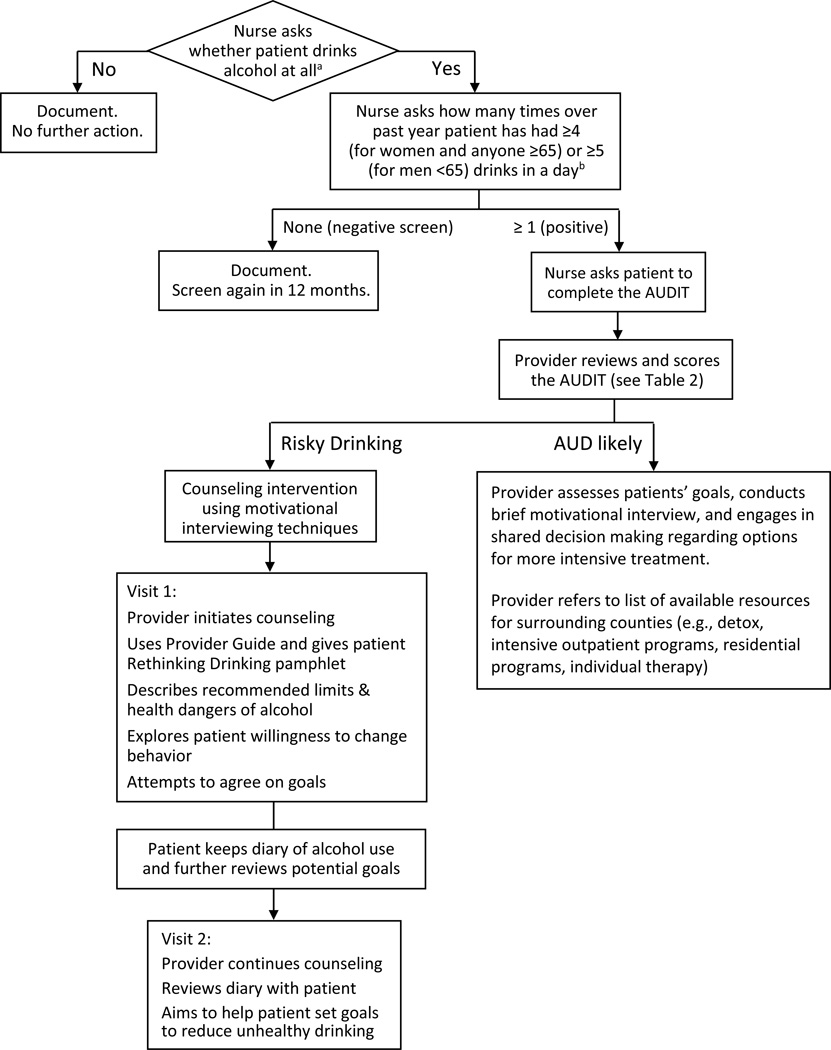

Work on the program began in 2012. The program was initiated in late April 2013 for faculty patients and expanded to include resident patients in November 2013. We aimed to implement a program to (1) screen all patients for unhealthy alcohol use, (2) identify patients with risky drinking who could benefit from primary care-based counseling, (3) use motivational interviewing techniques to counsel patients with risky drinking, and (4) provide appropriate referral resources for patients with AUD. The program included a systematic screening approach, a process for providing behavioral counseling, and training for providers. Figure 1 provides an overview of the program process.

Figure 1.

Screening and counseling program process

Screening Program

We used the single-question screen recommended by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), followed by the full 10-question Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Updated 2005 Edition) for those with positive screens. (Jonas et al., 2012b) Single-question screens require less than 1 minute to administer and have sensitivities of 0.82 to 0.87 and specificities of 0.61 to 0.79 for detecting unhealthy alcohol use in adults in primary care. (Jonas et al., 2012b)

To screen patients, nurses were prompted to ask whether the person drinks alcohol at all, and then, if yes, to ask how many times over the past year they've had ≥4 (for women and those ≥65) or ≥5 (for men under 65) drinks in a day (Figure 1, Appendix 2). For patients with a positive screen (answering ≥1 times), nurses asked patients to complete the AUDIT (Appendix 3), which was printed on pink paper. When they saw the AUDIT form, providers were visually prompted to review it and calculate the score, which they used to help distinguish patients with an AUD from those with risky drinking (Figure 1). Table 2 summarizes the AUDIT scores used to indicate whether an AUD was likely.

Table 2.

Using the AUDIT to help with screening-related assessment. Does the person have an alcohol use disorder?

| AUDIT score | Likelihood of alcohol use disorder | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |

| <6 | <4 | Alcohol use disorder is unlikely Proceed with motivational interviewing for risky drinking |

| 6-14 | 4-12 | Review questions 4-6:

|

| ≥15 | ≥13 | Alcohol use disorder is very likely. Consider referral. |

Counseling Program

When providers determined that a patient had risky drinking behaviors, but not an AUD, they initiated a 2-visit counseling intervention. The intervention was designed based on the systematic review conducted for the USPSTF, which found that counseling interventions require more than simple advice to improve drinking outcomes; the best evidence was for brief (10–15 min) multi-contact (≥2 visits) interventions. (Fleming et al., 1997; Jonas et al., 2012a) Behavioral counseling interventions aim to moderate a patient’s alcohol consumption to sensible levels and to reduce or eliminate risky drinking. Effective programs have included motivational interviewing, feedback, written health education or self-help materials, advice-giving, drinking diaries, and problem-solving exercises to complete at home. (Jonas et al., 2012a)

We incorporated techniques from motivational interviewing, an evidence-based behavioral counseling approach originally developed to address substance use (particularly problem drinking) that uses a patient-centered, guiding (rather than directing) style to elicit behavior change by helping patients to explore and resolve ambivalence, and by eliciting patients’ own motivations for change. (Miller & Rollnick, 1991; Rollnick, Butler, Kinnersley, Gregory, & Mash, 2010) This approach has been shown to elicit change in a wide range of behaviors and healthcare settings. (Lundahl, Moleni, Burke, Butters, Tollefson, Butler et al., 2013; Rollnick et al., 2010; Rubak, Sandbaek, Lauritzen, & Christensen, 2005)

A Provider Guide was developed to support clinicians conducting motivational interviews (Appendix 4). It was organized using a 5 A’s approach: Assess, Advise, Assist, Agree, and Arrange follow up, and included motivational interviewing techniques corresponding to each step. We also developed a pamphlet for patients titled Rethinking Drinking that provided information about health risks, recommended drinking limits, definitions of standard drinks, a menu of options/goals for reducing risky drinking, and a diary to record alcohol consumption (Appendix 5). Both the Provider Guide and Rethinking Drinking pamphlet included portions of publicly available materials developed by the NIAAA.

We used a 2-visit approach for behavioral counseling. During the first visit, physicians initiated counseling, provided information about recommended drinking limits and health problems that can occur as a result of risky drinking, explored patient’s willingness to change behavior, and gave patients the Rethinking Drinking pamphlet. Depending on competing demands, the patient and provider may or may not have reached agreement regarding goal setting at the initial visit. In cases where they could not achieve agreement, providers asked patients if they would keep a diary of alcohol use and review the list of potential goals before the next visit. At the second visit (four weeks later), providers continued the counseling intervention, reviewed the diary with the patient, and aimed to help the patient set goals to reduce unhealthy drinking.

If providers identified an AUD, they conducted brief motivational interviewing to determine whether the patient was willing to set a goal of abstinence or not, and then engaged in shared decision making regarding options for more intensive treatment. A list of available resources was developed to aid providers, organized both by type of service (e.g., detoxification, intensive outpatient programs, residential programs, individual therapy) and by county. (UNC School of Medicine, 2014)

Faculty and Resident Training

To increase provider confidence, we implemented a two-phase training in motivational interviewing. In phase one, teaching faculty were trained in motivational interviewing techniques and the intervention protocol. This was achieved during a half-day retreat that included overview of the foundation and principles of motivational interviewing; didactic material on specific techniques including reflective listening, open questions, elicit-provide-elicit, asking permission, and an importance and confidence exercise; demonstration of techniques via videos and live role-play by counselors trained in motivational interviewing; and opportunities for faculty to practice. During the retreat, faculty pilot-tested a draft of the Provider Guide by taking turns role-playing. The materials were then revised based on feedback prior to implementing their use. In phase two, a curriculum to train residents was created and delivered during pre-clinic educational conferences.

Process Refinement

Beginning Spring 2012, we utilized the Model for Improvement (from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement) and small tests of change to refine the processes and content. (Langley, 2009) For example, we first evaluated the effects of adding the single-question screener on usual workflows; upon agreeing on an effective, nondisruptive approach, we then tested various options for administering the AUDIT to those with a positive screen (e.g., by nurse, by provider) and for saving the AUDIT results. After testing the screening processes with several nurses, providers, and patients, the team gathered staff and provider feedback. Refinements were made before assessing the next iteration on another group of patients. Three Internal Medicine residents (ES, JK, MD) were involved in the improvement processes as part of quality improvement-focused outpatient training months.

Program Evaluation

Our primary outcome measures were the number and proportion of patients screened, the proportion with positive single-question screens who completed the AUDIT, and the proportion of eligible patients who were appropriately offered counseling for risky drinking. Secondary outcome measures were faculty and resident comfort with counseling. Secondary outcome measures were assessed by an anonymous survey that was emailed to residents and faculty.

We evaluated the program periodically (by assessing screening and intervention rates) and reported results to physicians and nurses. Evaluations continued through early April, 2014, when our healthcare system changed to a new electronic health record (and our visit-based prompting system was discontinued).

RESULTS

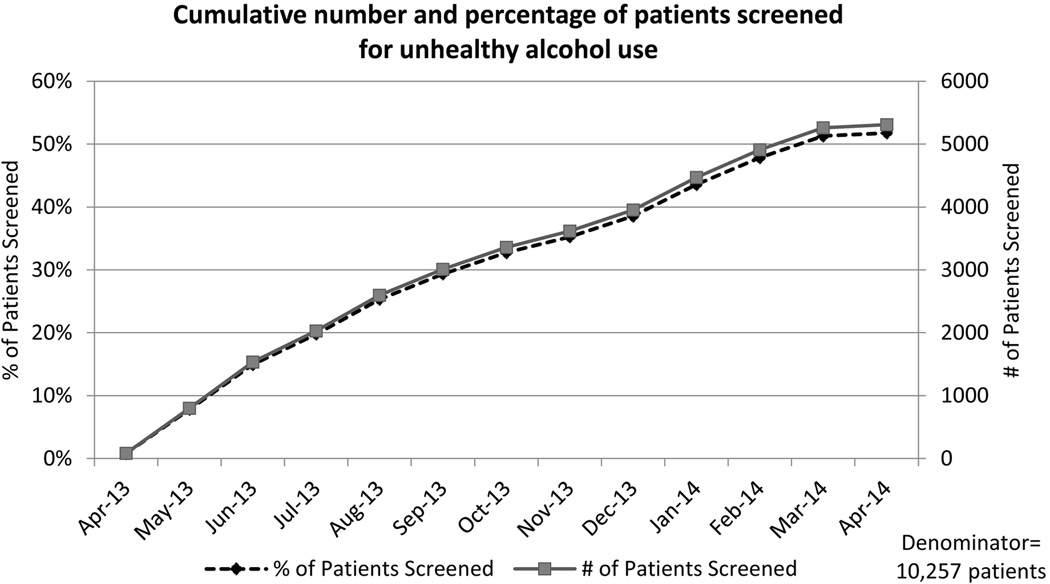

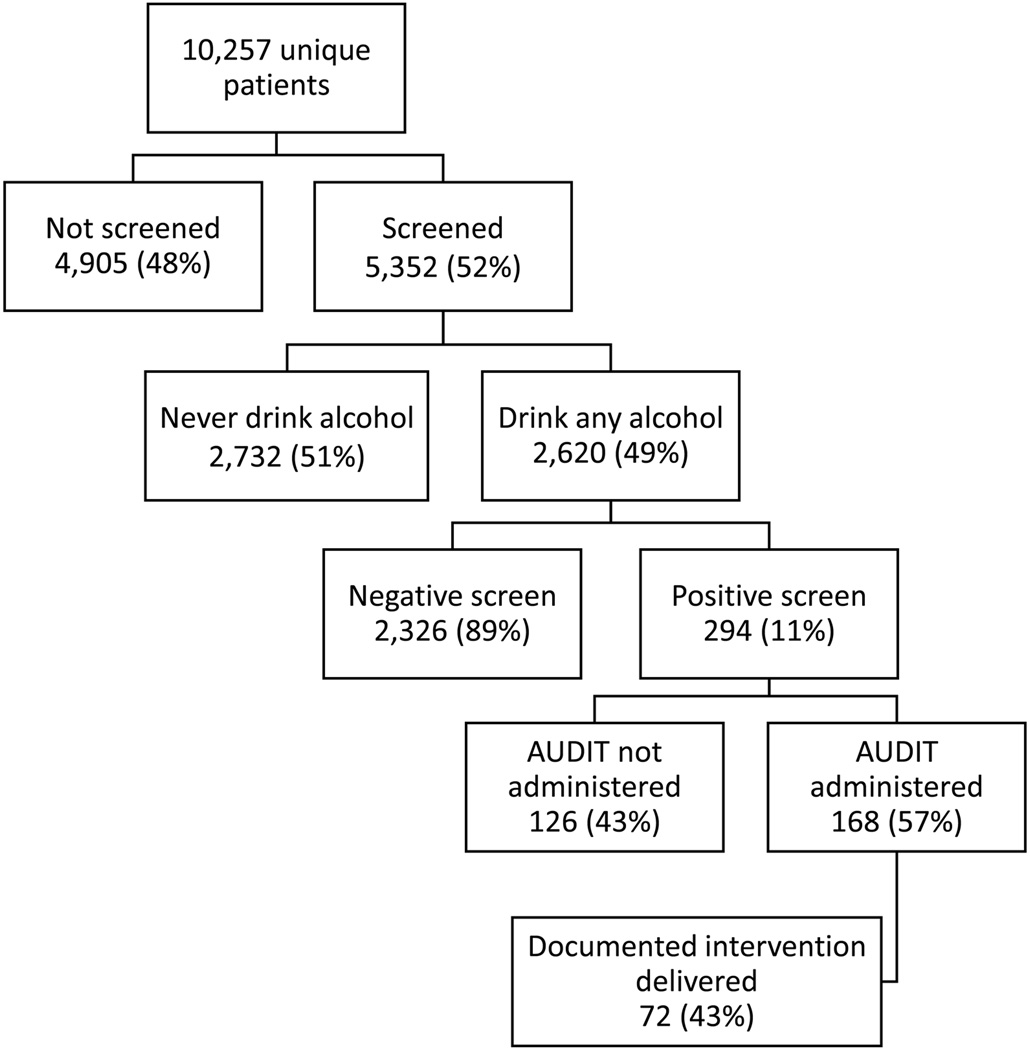

Figure 2 shows the cumulative number and percentage of patients screened over this period. Figure 3 shows our primary outcomes. We screened 52% of our patients (N=5,352). Of those, about half (51%) reported that they never drink alcohol, consistent with what we expected based on data for North Carolina from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013a, 2015) We identified 294 patients with positive screens for unhealthy alcohol use (5.5% of all those screened; 11% of those who sometimes drink alcohol). For those 294, 168 (57%) had documentation of a completed AUDIT and 72 had documentation of an appropriate intervention.

Figure 2.

Cumulative number and percentage of patients screened for unhealthy alcohol use

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients screened, screening results, and interventions delivered

After the implementation, the vast majority of faculty and resident respondents to an anonymous survey indicated that they were comfortable with providing counseling for risky drinking (9 /11 faculty [82%] and 28/32 residents [88%]).

DISCUSSION

We successfully implemented a screening program to identify patients with unhealthy alcohol use that included provider training and development of structured processes of care to guide counseling interventions. We effectively screened over half of all patients who attended our practice and counseled many patients found to have risky drinking. We learned that about half of our patients never drink alcohol; these patients can be excluded from future screening. Although we reached a large number of patients, we have not yet achieved the goal of screening all patients, nor our goal of assessing and providing appropriate interventions for all of those identified with unhealthy alcohol use. This was not surprising for several reasons: (1) our priority-based screening and prevention processes limited nurse prompts to the top 3 health issues for each patient, and screening for unhealthy alcohol use often ranked below other priorities, (2) many visits in our clinic are for urgent care visits or with clinical pharmacists for anticoagulation services, and we have not yet attempted to screen during those visits (but they were included in the denominator of visits because we intended to expand screening to those visits after refining the process, and we want the data to show both our progress and the volume of patients that we still needed to reach in order to screen our complete clinic population), and (3) the evaluation period only covers one year; over time more patients would be reached, as they have continued contact with our practice.

One key challenge that we encountered was training a large number of faculty and residents. Another key challenge was the competing time demands providers faced. Many providers commented on the challenge of handling a positive screen when patients are typically being seen for other reasons. The addition of a 10 to 15-minute counseling intervention to a busy visit agenda is sometimes infeasible; even when feasible, it can require providers to trade-off addressing other issues, interfere with clinic flow and time for other patients, and create stress for providers. In anticipation of the challenges, we structured the program so that providers could start the counseling intervention at the initial visit and then schedule a 1-month follow up to continue it. However, this did not always reduce the barrier to counseling implementation. Of those with a positive screen, we found documentation of a completed AUDIT for 57%; and 43% of those had documentation of an intervention delivered (Figure 3). Possible reasons that uptake was not greater include competing time demands, not all providers had received the training, poor documentation (i.e., the AUDIT or intervention had actually been completed but was not documented and was lost), and the fact that this was a newly implemented process that still needed further evaluation and improvement.

To further improve our program, we aim to first re-implement it and screen the remainder of our population, with modifications that take advantage of our new electronic health record (EPIC). We are still in the process of re-implementing some of our screening and prevention programs. Other next steps are to assess barriers to counseling and referral, and to improve the consistency with which we counsel, refer patients with AUDs, and document our interventions. In addition, although the current evaluation did not include assessment of intervention outcomes (e.g., reduction in risky drinking), we aim to develop a registry and disease management program for our patients with unhealthy alcohol use so that they may be tracked (e.g., assessing reduction in risky drinking or treatment for AUD) and additional interventions tested. For example, we plan to test the feasibility and benefits of incorporating online interventions within our program.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank (1) UNC IMC faculty, staff, and residents for their support and involvement in this program and (2) Colleen Barclay, MPH for her excellent support related to formatting, editing, and submitting this manuscript. The faculty training in motivational interviewing was provided by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI50410).

Financial Support: Dr. Golin and Ms. Grodensky’s efforts were partially supported by NIH grant P30 AI50410; Dr. Ratner was supported by Access Care North Carolina.

Biographies

Daniel E. Jonas, MD, MPH is Associate Professor of Medicine and Section Chief for Research in the Division of General Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His areas of expertise include unhealthy alcohol use, primary care, comparative effectiveness, evidence-based medicine, prevention, screening, and chronic disease management.

Thomas Miller, MD is Professor of Medicine in the Division of General Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology at UNC-Chapel Hill. He has expertise in disease prevention, disease management, geriatrics, travel medicine, practice management and quality improvement.

Shana Ratner, MD is Assistant Professor in the Division of General Medicine and Clinical Epidemiology at UNC-Chapel Hill and Medical Director of the Internal Medicine Clinic, and has expertise in quality improvement and care delivery.

Brooke McGuirt, MBA was the Quality Coordinator for the UNC-Chapel Hill Internal Medicine Clinic, and is currently Population Health Operational Project Manager within the Practice Quality and Innovation Department of UNC’s School of Medicine.

Carol E. Golin, MD is an Associate Professor of Medicine in the Departments of Medicine and Health Behavior and Health Education at UNC-Chapel Hill, as well as Co-director of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Research Core, UNC Center for AIDS Research.

Catherine Grodensky, MPH is a Research Associate at the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Emily Sturkie, MD is an Internal Medicine Resident in the Department of Medicine at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Jennifer Kinley, MD was a resident in UNC-Chapel Hill’s Internal Medicine Residency Program during the project.

Maureen Dale, MD was a resident in UNC-Chapel Hill’s Internal Medicine Residency Program during the project.

Michael Pignone, MD, MPH, is Professor of Medicine, Chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine at UNC-Chapel Hill, and Director of UNC’s Institute for Healthcare Quality Improvement.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Preliminary results of this work were presented as a poster at the SGIM 37th Annual meeting, San Diego, CA, April 25, 2014. “Implementation of a Screening Program to Address Unhealthy Alcohol Use in an Academic General Internal Medicine Clinic.”

REFERENCES

- Bondy SJ, Rehm J, Ashley MJ, Walsh G, Single E, Room R. Low-risk drinking guidelines: the scientific evidence. Can J Public Health. 1999;90(4):264–270. doi: 10.1007/BF03404129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanaugh JJ, Jones CD, Embree G, Tsai K, Miller T, Shilliday BB, Ratner S. Implementation Science Workshop: primary care-based multidisciplinary readmission prevention program. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(5):798–804. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2819-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost--United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(37):866–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. BRFSS Prevalence & Trends Data. [Retrieved February 23, 2016];2013a from http://nccd.cdc.gov/brfssprevalence/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=DPH_BRFSS.ExploreByLocation&rdProcessAction=&SaveFileGenerated=1&rdCSRFKey=503199fc-0542-4ed6-a807-c8b8106efa4e&islLocation=37&islClass=CLASS01&islTopic=Topic03&islYear=2013&hidLocation=37&hidClass=CLASS01&hidTopic=Topic03&hidTopicName=Alcohol+Consumption&hidYear=2013&irbShowFootnotes=Show&iclIndicators_rdExpandedCollapsedHistory=&iclIndicators=DRNKANY5&hidPreviouslySelectedIndicators=&DashboardColumnCount=2&rdShowElementHistory=&rdScrollX=0&rdScrollY=320&rdRnd=4248.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats: Alcohol Use. [Retrieved March 4, 2015];2013b Feb 6; 2015. from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/alcohol.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and Public Health. [Retrieved February 23, 2016];2015 from http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/data-stats.htm.

- Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y. Alcohol-attributable fraction for injury in the U.S. general population: data from the 2005 National Alcohol Survey. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(4):535–538. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PJ. Paying the Tab: The Costs and Benefits of Alcohol Control. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med. 2004;38(5):613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Paddock SM, Burnam A, Kung FY. Identification of and guidance for problem drinking by general medical providers: results from a national survey. Med Care. 2005;43(3):229–236. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt DA, Malone RM, Bryant ME, Kosnar MC, Corr KE, Rothman RL, Pignone MP. A heart failure self-management program for patients of all literacy levels: a randomized, controlled trial [ISRCTN11535170] BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R. Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers. A randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices. JAMA. 1997;277(13):1039–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham C. Think you drink a lot? This chart will tell you. [Retrieved March 4, 2015];2014 Sep 25; from http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2014/09/25/think-you-drink-a-lot-this-chart-will-tell-you/ [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Bryant Shilliday B, Laundon WR, Pignone M. Patient time requirements for anticoagulation therapy with warfarin. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(2):206–216. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09343960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Evans JP, McLeod HL, Brode S, Lange LA, Young ML, Weck KE. Impact of genotype-guided dosing on anticoagulation visits for adults starting warfarin: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14(13):1593–1603. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, Brown JM, Brownley KA, Council CL, Harris RP. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2012a;157(9):645–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Brown JM, Amick HR, Brownley KA, Council CL, Harris RP. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 64. (Prepared by the RTI International–University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290 2007 10056 I.) AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC055-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012b. Screening, Behavioral Counseling, and Referral in Primary Care to Reduce Alcohol Misuse. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiser K, Jonas D, Warner Z, Scanlon K, Shilliday BB, DeWalt DA. A randomized controlled trial of a literacy-sensitive self-management intervention for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(2):190–195. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1867-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley GJ. The Improvement Guide : A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Le KB, Johnson JA, Seale JP, Woodall H, Clark DC, Parish DC, Miller DP. Primary care residents lack comfort and experience with alcohol screening and brief intervention: a multi-site survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3184-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, Butters R, Tollefson D, Butler C, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight-Eily LR, Liu Y, Brewer RD, Kanny D, Lu H, Denny CH, Collins J. Vital Signs: Communication Between Health Professionals and Their Patients About Alcohol Use — 44 States and the District of Columbia, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(01):16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick SR. Motivational interviewing: preparing people to change behavior. New York: Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer VA Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(3):210–218. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician's Guide. [Retrieved June 15, 2015]; (Updated 2005 Edition). from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/clinicians_guide.htm.

- Potisek NM, Malone RM, Shilliday BB, Ives TJ, Chelminski PR, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP. Use of patient flow analysis to improve patient visit efficiency by decreasing wait time in a primary care-based disease management programs for anticoagulation and chronic pain: a quality improvement study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GL, Graham K, Irving H, Kehoe T, Taylor B. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2010;105(5):817–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Butler CC, Kinnersley P, Gregory J, Mash B. Motivational interviewing. BMJ. 2010;340:c1900. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RL, DeWalt DA, Malone R, Bryant B, Shintani A, Crigler B, Pignone M. Influence of patient literacy on the effectiveness of a primary care-based diabetes disease management program. JAMA. 2004;292(14):1711–1716. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RL, Malone R, Bryant B, Shintani AK, Crigler B, Dewalt DA, Pignone MP. A randomized trial of a primary care-based disease management program to improve cardiovascular risk factors and glycated hemoglobin levels in patients with diabetes. Am J Med. 2005;118(3):276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RL, So SA, Shin J, Malone RM, Bryant B, Dewalt DA, Dittus RS. Labor characteristics and program costs of a successful diabetes disease management program. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(5):277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):596–607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp042262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9662):492–501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalala D U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 10th Special Report to the U.S. Congress on Alcohol and Health: Highlights From Current Research. [Retrieved March 4, 2015];2000 from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/10report/intro.pdf.

- Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E109. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNC School of Medicine; Department of Medicine; Division of General Medicine & Clinical Epidemiology. Alcohol Screening & Counseling. [Retrieved March 4, 2015];2014 from http://www.med.unc.edu/im/staff/clinic/programs/copy_of_alcohol-screening-counseling. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson DC, Manning BK, Galliher JM, Dickinson LM, Pace WD, Turner BJ. Alcohol and sleep problems in primary care patients: a report from the AAFP National Research Network. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(6):484–492. doi: 10.1370/afm.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.