Abstract

Background

The risk of early revision because of pseudotumors in patients who have undergone large-head metal-on-metal (MoM) total hip arthroplasty (THA) is well documented. However, the natural history of asymptomatic pseudotumors or of MoM articulations without pseudotumors is less well understood. The aim of our study was to investigate the natural history of primary MoM THA at mid-term followup.

Questions/purposes

The purposes of this study were: (1) Did previously detected pseudotumors persist or worsen in asymptomatic patients at mid-term followup; and if so, did any of them require revision THA? (2) Did new pseudotumors form in asymptomatic patients at mid-term followup? (3) What happened to serum trace metal ions at mid-term followup? (4) Were postoperative patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) maintained at mid-term followup?

Methods

Seventy-one patients who underwent a MoM THA using a Metasul LDH implant with a Durom acetabular cup and an M/L Taper stem between September 2005 and October 2008 were reviewed. All patients for this study were part of two previously published studies from our early followup. Data from the previous studies were used for comparison only. Two of the 71 patients (2.8%) were lost to followup. The mean age at operation was 56 years (range, 34–68 years). There were 24 female patients. All patients had serum trace metal ions testing, ultrasound imaging, and PROMs at a mean 3.5 years (early followup) after the index operation (range, 3–5 years) and delayed followup at a mean 7 years (range, 6.5–9 years). The indication to undertake revision THA was based on clinical evaluation and not solely on the investigation results.

Results

Twenty-three of 71 patients (32%) had a positive ultrasound scan for pseudotumor at early followup. Of these, eight patients underwent revision THA (11% of MoM THA or 35% of patients with an early positive ultrasound scan). The mean time between positive ultrasound scan and revision surgery was 13 months (range, 5–22 months). Of the remaining 15 patients with pseudotumor noted on early ultrasound, 12 had persistent pseudotumor, two resolved, and one was lost to followup. Six patients (13%) with a normal ultrasound scan at early followup showed new ultrasound findings at delayed followup. Of these, four (8%) were conclusively diagnosed as pseudotumor and one was revised. Serum trace metal ion increased at mid-term followup in the seven cases that showed an increase in volume of pseudotumor. Of the five patients in whom the volume of pseudotumor decreased on ultrasound at mid-term followup, three showed a decrease in serum trace ions levels, whereas two showed an increase. New-onset pseudotumors at mid-term followup was associated with an increase in serum trace metal ions at mid-term followup only in two of six cases. PROMs at mid-term followup of patients in this study remain high.

Conclusions

At mid-term followup, approximately 35% of patients who develop an early pseudotumor undergo revision arthroplasty, whereas the remaining are asymptomatic. The incidence of new-onset ultrasound findings suggestive of pseudotumors at mid- to long-term followup is approximately 8% and these require continued surveillance.

Level of Evidence

Level II, prognostic study.

Introduction

Large-head metal-on-metal (MoM) THAs have the theoretical advantages of superior wear characteristics [9, 12] and improved stability [6, 7, 17, 21, 22]. However, their routine use is currently discouraged as a result of concerns regarding elevated serum metal ions and their local [3–5, 8, 13, 19, 20, 25] and systemic side effects [2, 10, 12, 15, 18, 23, 26].

Although early failure of MoM articulations from pseudotumor formation is well documented, the natural history of asymptomatic pseudotumors is less well known. A previous study [1] published from our institution looked at the early (mean 26 months) followup results of asymptomatic pseudotumors in a cohort of 20 patients. The study found that five patients underwent revision surgery and 15 remained nonrevised. Among the 15 nonrevised patients, pseudotumors increased in size in six, disappeared completely in three, and decreased in size in one case. In five revised patients, pseudotumors completely disappeared in four patients and decreased in size in one. However, this study had the limitations of a small study cohort and diverse patient group (hip resurfacing, large-head MoM, and metal-on-polyethylene pseudotumors were included). Also, no patient who had a negative first ultrasound was included in the followup period. Several other authors have documented the frequency with which pseudotumors after MoM THA [14, 16, 25, 27]. However, the natural history of asymptomatic pseudotumors in large-head MoM hip replacements remains unclear. Understanding this will help surgeons with counseling patients and deciding followup and surveillance of MoM THA. It also provides useful insight into the behavior of metal bearings in THA.

The aim of our study was to investigate the natural history of primary large-head MoM THA at mid- to long-term followup. To answer this question, we looked at the persistence of pseudotumor on ultrasound scans at mid-term followup in asymptomatic patients as well as the incidence of pseudotumor at mid-term followup in previously negative pseudotumors. In these two groups we also investigated the change in serum trace metal ions and quality-of-life outcomes between mid-term followup. Specifically, we sought to answer the following questions: (1) Did previously detected pseudotumors persist or worsen in asymptomatic patients at mid-term followup; and if so, did any of them require revision THA? (2) Did new pseudotumors form in asymptomatic patients at mid-term followup? (3) What happened to serum trace metal ions at mid-term followup? (4) Were postoperative PROMs maintained at mid-term followup?

Patients and Methods

Institutional ethics review board approval was obtained and all patients gave their informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

Between September 2005 and October 2008, 2073 primary hip arthroplasties were performed in our center. Of these 360 (17.4%) were primary large-head, MoM THAs using the Durom® MoM articulation and a M/L Taper stem (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA). The mean age at surgery in the MoM THA cohort was 54.5 years (range, 17–77 years). There were 102 females (28%) and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 29 kg/m2 (range, 17–46 kg/m2). The remaining patients underwent metal-on-polyethylene THA (mean age, 63 years; range, 19–92 years). The patients receiving MoM THA were significantly younger (Mann-Whitney U-test, p < 0.0001). Metal-on-metal articulation THA was preferred in the younger patient cohort undergoing THA as a result of better tribologic properties.

We aimed to investigate the natural history of asymptomatic pseudotumors at mid-term followup. From the 360 patients who underwent MoM THA, we identified a representative cohort of 71 patients who were clinically asymptomatic and had no pseudotumors identified on ultrasound scan at early followup who had previously been evaluated for two other studies [12, 27]. Patients in this group (Table 1) were comparable to our 360 patients undergoing MoM THA (mean age at surgery, 56 years [range, 34–68 years]; 33% female; and average BMI 27 kg/m2 [range, 20–43 kg/m2]). Patients for both of those studies had been identified after informed consent to participate and WOMAC score greater than 75. Forty patients had participated in a study investigating the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound scans for pseudotumors [12] and 31 patients had participated in a study investigating the prevalence of pseudotumors in asymptomatic patients at early followup [27].

Table 1.

Demographics of the study cohort

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 71 |

| Patient sex | 24 female, 47 male |

| Age at index surgery (mean years; range) | 56 (34–68) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2; range) | 27 (20–43) |

| Mean time from surgery to early investigations (years; range) (early followup) | 3.5 (3–5) |

| Mean time from surgery to mid-term investigations (years; range) (delayed followup) | 7 (6.5–9) |

All patients underwent MoM hip arthroplasty using a Metasul LDH implant with a Durom acetabular cup (Zimmer Inc) between September 2005 and October 2008 and were asymptomatic with regard to their MoM hip articulations at the time of the previous study [12, 27]. All 71 patients had undergone investigations with serum trace metal ion testing, plain hip and pelvis radiographs, ultrasound imaging, and patient-reported outcome measures as part of previous studies [12, 27] between 3 and 5 years postoperatively (early followup) and 58 patients underwent those investigations one more time at 6.5 to 9 years (delayed followup). Our previously published studies [12, 27] documented the early followup. The data published earlier have been used for comparison with the current study, which looks at the mid-term results.

Only 58 patients underwent delayed scanning and the reasons for this were as follows: (1) three patients were completely asymptomatic and refused further investigations; (2) two patients were lost to followup; and (3) eight patients underwent conversion to ceramic-on-highly crosslinked polyethylene for painful MoM THA. There were 47 male patients with a mean BMI of 27 kg/m2 (Table 1). The bias toward male patients is reflective of the fact that more male patients were offered large-head MoM hip replacement than female patients. This bias was also noted in patients undergoing THA in our institution between September 2005 and October 2008. Compared with 58% (994 of 1713) females among patients undergoing metal-on-polyethylene THA, only 28% (102 of 360) of patients undergoing MoM THA were female.

Ultrasound Imaging

An experienced musculoskeletal sonographer (SJ) performed the ultrasound examinations. A standardized template was used to conduct the scans, which were performed using a Siemens Antares TM Ultrasound System (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Mountain View, CA, USA). The Siemens VFX9-4 linear transducer and/or the Siemens CH6-2 curvilinear transducer was used for anterior, posterior, and/or lateral views depending on each patient’s specific body habitus; body habitus affected the choice of transducers, but all images were obtained on all patients. Acquisition time was 20 minutes. The presence, size, and position of any fluid, cystic mass, or solid mass related to the hip were recorded along with any involvement of neurovascular structures. The volume of any fluid or mass was calculated by multiplying the maximum recorded dimensions in millimeters in each of three planes and dividing by 1000 to convert to volume in cubic centimeters. The radiologist was asked to definitively state whether the scan was normal or abnormal, and if the latter, the radiologist categorized it as one of three possible abnormalities: (1) a solid mass; (2) a cystic mass or a complex fluid collection; or (3) a simple fluid collection. On ultrasound, a simple fluid collection was defined as anechoic with increased through transmission and a well-defined posterior wall. A complex fluid collection/cystic mass contained debris (internal echoes), septations, or both. The following measurements were made between early and mid-term followup scans. Outcomes of interest were (1) the percentage of MoM THAs with persistent ultrasound findings between repeat scans; (2) the percentage of MoM THAs developing new pseudotumors between repeat ultrasounds; and (3) percentage of MoM THAs with progression of ultrasound findings between repeat scans. Progression was defined as change in grade when there was change in consistency (fluid < cystic < solid changes) and change in size when a change in volume was noted.

Revision Procedures for Pseudotumors

In 2014 (a minimum 6.5 years from surgery; maximum, 9 years; mean, 7 years), after ethical approval, the clinical records of these 71 patients were reviewed to identify patients who had undergone revision surgery. At a mean of 5 years from the index procedure (range, 3–6 years), eight patients with pseudotumors had undergone revision THA for symptomatic pseudotumors. The indication for revision was symptomatic hip pain affecting sleep, activities of daily living, and quality of life. Ultrasound findings and serum metal ions were not used to guide the decision to revise MoM THA in asymptomatic patients. The mean normalized WOMAC score dropped from 98 (range, 96–100; SD 1.48) at the time of the ultrasound scan to a mean of 85 (range, 76–90; SD 5.3) before revision THA. The mean time between positive ultrasound scan and revision surgery for symptomatic MoM articulation was 13 months (range, 5–22 months). These patients did not undergo a second ultrasound scan. All revised cases were noted to have cystic or solid pseudotumor on ultrasound scan before revision (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ultrasound findings and serum metal ions of the eight cases revised for symptomatic MoM articulation

| Case number | Ultrasound findings | Metal ions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection | Volume (cc) | Cr (μg/L) | Co (μg/L) | |

| 1 | SM | 17 | 4 | 3 |

| FC | 32 | |||

| 2 | CM | 176 | 50 | 59 |

| 3 | SMa | 437 | 11 | 98 |

| SMb | 43 | |||

| SMc | 80 | |||

| 4 | SMa | 134 | 2 | 3 |

| SMb | 134 | |||

| 5 | SM | 172 | 5 | 8 |

| CM | 361 | |||

| 6 | SM | 14 | 4 | 6 |

| FC | 0.4 | |||

| 7 | CMa | 123 | 2 | 11 |

| CMb | 339 | |||

| 8 | CM | 499 | 4 | 6 |

MoM = metal-on-metal; Cr = chromium; Co = cobalt; SM = solid mass; CM = cystic mass; FC = fluid collection; where the ultrasound showed more than one collection, their volumes were separately measured and documented as a, b, c, etc.

Serum Trace Metal Ions

Serum trace metal ions were collected as described in our previous study [27]. Blood samples were obtained with use of a BD Vacutainer Safety-Lok Blood Collection Set (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The first 5 mL of blood was discarded to avoid possible contamination from the needle. A second 5 mL of blood was collected, and serum levels of cobalt and chromium were measured at the Trace Elements Laboratory–London Health Sciences Centre (London, Ontario, Canada) with use of inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Thermo Fisher ELEMENT 2, High Resolution Sector Field Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer [HR-SF-ICP-MS];Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Patient-reported Outcome Measures

All patients were invited to complete quality-of-life assessment at the time of the study. The patients were minimum 6.5 years from surgery (maximum, 9 years; mean, 7 years). Outcomes studied were WOMAC [2], SF-12 [3], Oxford Hip Score [4], and UCLA [5] scores in all cases. Early and mid-term scores were compared. All WOMAC and Oxford Hip Scores were normalized to be out of 100 with higher scores indicating better function. In addition, any patients who were revised for pseudotumor had patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) collected at the time of the initial ultrasound scan when they were asymptomatic and just before the revision operation.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics was used to express all results. Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare any difference in serum trace metal ions in patients who had undergone revision and the rest of the cohort.

Results

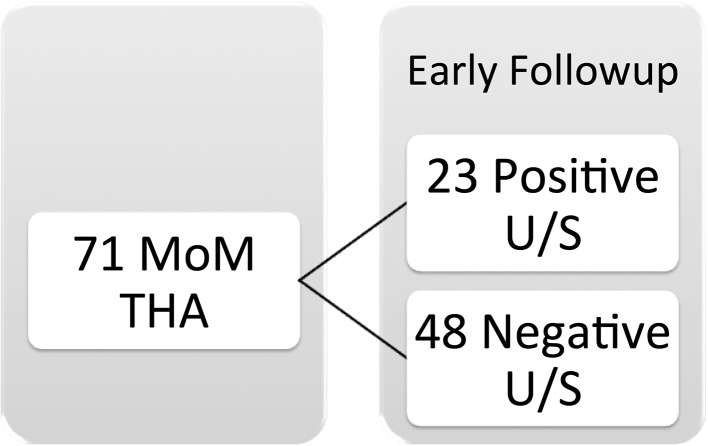

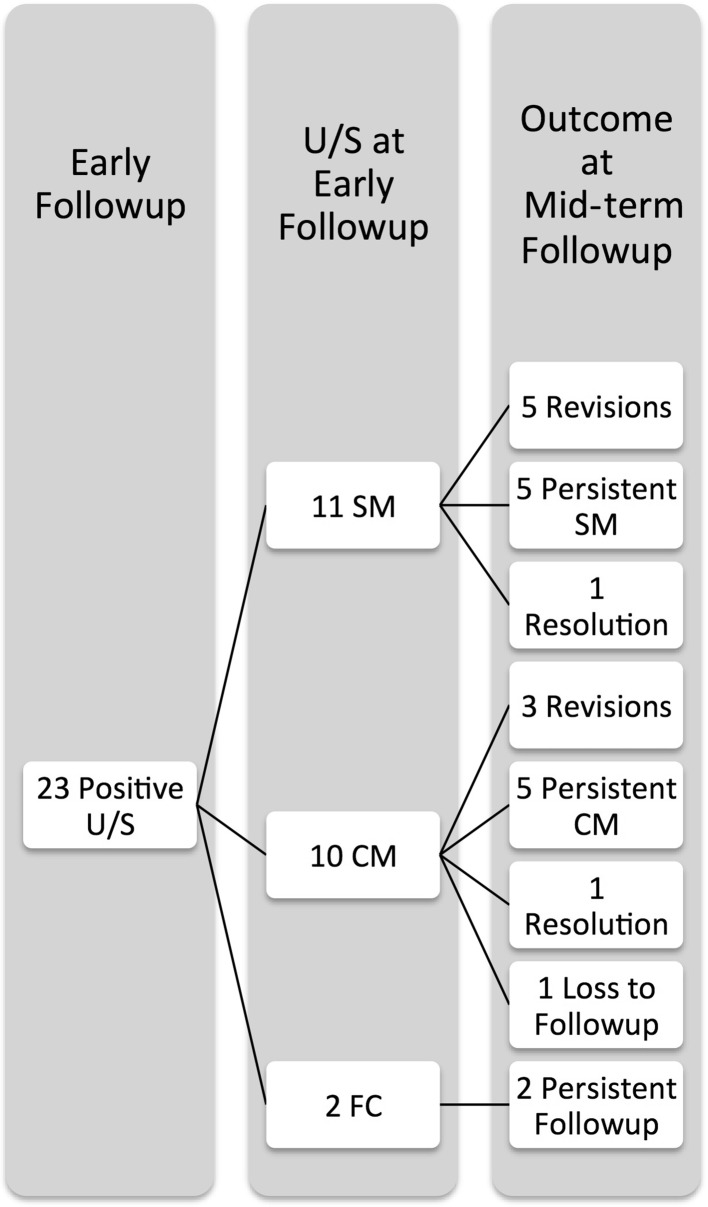

Twenty-three of 71 patients demonstrated a pseudotumor at early followup, and eight of these underwent early revision. Of the remaining 15 patients with pseudotumor noted on early ultrasound, one was lost to followup, two showed complete resolution, and 12 demonstrated persistent pseudotumor but remained asymptomatic. Twenty-three patients (32%) had positive a ultrasound scan for fluid, cystic, or solid mass at early followup (Fig. 1). This included eight patients who underwent revision THA (11% of MoM THA or 35% of early positive ultrasound scans) for pseudotumors. All of these patients had solid or cystic masses and none had an isolated fluid collection. This left 15 patients who were followed and not revised initially. One patient did not present for repeat scans. Of the remaining 14 patients, 12 (52% of the cohort with an initial abnormal ultrasound scan) had persistent positive ultrasound scans but remained asymptomatic and two (9% of the cohort with an initial abnormal ultrasound scan) patients showed complete resolution of any fluid or cystic lesions (Fig. 2). Twelve of the 58 patients rescanned patients (21%) had persistent positive ultrasound scan for pseudotumor at mid-term followup. We noticed no progression of grade of pseudotumor (solid versus cystic versus fluid) between the interval scans (Table 3). However, there was an increase in volume of the pseudotumor in 26% (six hips), a decrease in volume in 22% (five hips), and no change in volume in 4% (one hip).

Fig. 1.

The distribution of ultrasound findings in the 71 study subjects at early followup is demonstrated. U/S = ultrasound.

Fig. 2.

This is a comparison of the early and mid-term ultrasound findings in the 23 patients with early positive ultrasound scan. U/S = ultrasound; SM = solid mass; CM = cystic mass; FC = fluid collection.

Table 3.

Ultrasound and serum trace metal ions in patients with early positive ultrasound scan

| Case number (change size) | Early followup (3–5 years) | Mid-term followup (6.5–9 years) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound (size in cm3) | Metal ions (μg/L) | Ultrasound (size in cm3) | Metal ions (μg/L) | |||||

| Cr | Co | Cr | Co | |||||

| 1 (increase) | SMa | 18 | 3 | 7 | SM | 20 | 5 | 8 |

| FCa | 3 | |||||||

| SMb | 28 | |||||||

| FCb | 17 | |||||||

| 2 (increase) | SM | 13 | 2 | 3 | SM | 53 | 3 | 5 |

| 3 (increase) | SM | 48 | 3 | 7 | SMa | 116 | – | – |

| FC | 5 | SMb | 54 | |||||

| 4 (increase) | CM | 77 | 3 | 8 | CM | 102 | 3 | 9 |

| 5 (increase) | FC | 68 | 0.6 | 2 | FC | 80 | 0.9 | 2 |

| 6 (increase) | FC | 18 | – | – | FC | 39 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| 7 (static) | SM | 8 | 3 | 8 | SM | 8 | 5 | 6 |

| 8 (decrease) | CM | 14 | 2 | 2 | CM | 12 | 2 | 4 |

| FCa | 59 | |||||||

| FCb | 12 | |||||||

| 9 (decrease) | CM | 292 | 4 | 10 | CM | 267 | 13 | 16 |

| 10 (decrease) | CMa | 39 | 0.5 | 0.6 | CM | 19 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| CMb | 6 | |||||||

| 11 (decrease) | CM | 86 | 2 | 8 | CM | 29 | 5 | 12 |

| CM | 11 | |||||||

| 12 (decrease) | SM | 188 | 9 | 12 | SM | 40 | 6 | 8 |

| CM | 34 | CM | 40 | |||||

| 13 (resolved) | CM | 102 | 5 | 13 | – | 3 | 15 | |

| 14 (resolved) | SM | 12 | 3 | 3 | – | 2 | 3 | |

Cr = chromium; Co = cobalt; SM = solid mass; CM = cystic mass; FC = fluid collection; where the ultrasound showed more than one collection, their volumes were separately measured and documented as a, b, c, etc.

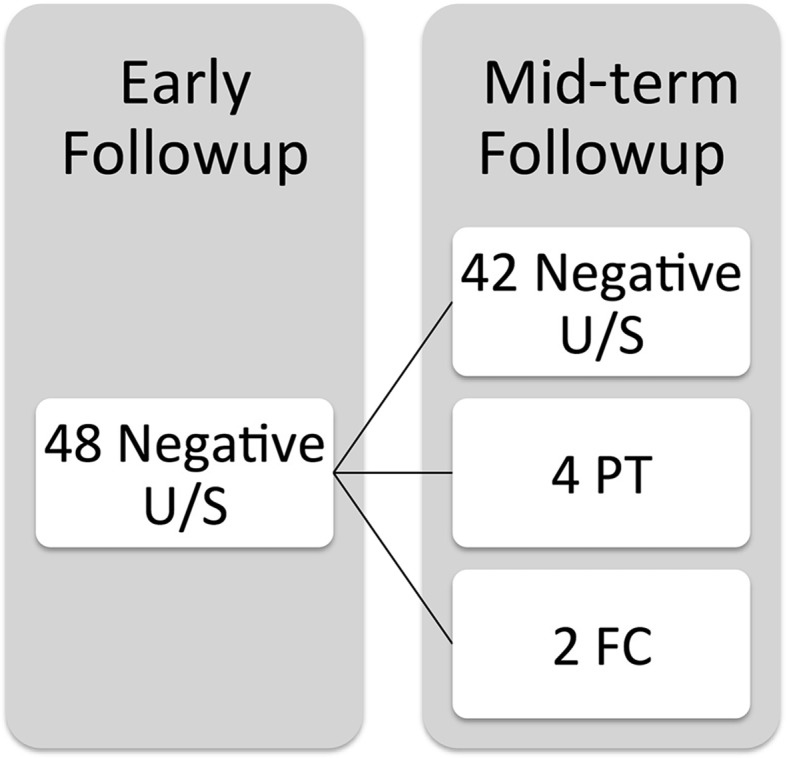

New pseudotumors were noted at mid-term followup in six (13%) patients with previously normal scans at early followup (Fig. 3) with new-onset fluid, cystic, and/or solid lesions noted on ultrasound. Of these six cases, in four cases, pseudotumor was conclusively diagnosed at mid-term followup (Table 4). All four cases had cystic masses, two with previous fluid collections (but no pseudotumor) and two cases with no previous fluid collection. One patient with new-onset pseudotumor at mid-term followup also required revision for symptomatic MoM THA.

Fig. 3.

The mid-term ultrasound findings in 48 patients with negative ultrasound scans at early followup are shown. U/S = ultrasound; PT = pseudotumour; FC = fluid collection.

Table 4.

PROMs at mid-term followup of patients with new-onset pseudotumors

| PROMs | Mean | Range | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford Hip Score | 82 | 27–100 | 29 |

| WOMAC pain | 83 | 25–100 | 30 |

| WOMAC stiffness | 77 | 25–100 | 28 |

| WOMAC function | 83 | 25–100 | 29 |

| WOMAC global | 82 | 25–100 | 29 |

| UCLA | 4 | 1–9 | 3 |

| SF-12 PCS | 42 | 30–57 | 9 |

| SF-12 MCS | 56 | 39–62 | 8 |

PROM = patient-reported outcome measure; PCS = physical component score; MCS = mental component score.

Serum trace metal ion test in the seven cases that showed an increase in volume of pseudotumor showed an increase in all cases (Table 3). The mean increase noted was of 0.82 μg/L (SD 0.73; range, 0.11–1.54 μg/L) for chromium and 1.07 μg/L for cobalt (SD 1.03; range, 0.34-2.53 μg/L). In the patient with static volume of pseudotumor, chromium level increased from 3.04 μg/L to 4.73 μg/L and cobalt level decreased from 7.59 μg/L to 6.28 μg/L. Of the five patients in whom the volume of pseudotumor decreased on ultrasound at mid-term followup, three showed a decrease in serum trace ions levels, whereas two showed an increase in levels. All of the eight patients revised for pseudotumors had elevated blood metal ion levels (mean chromium 10.2 μg/L [SD 16.54], cobalt 24.05 μg/L [SD 32.20]; range for chromium, 1.53–50.47 μg/L; range for cobalt, 2.55–97.92 μg/L; Table 2). There was no difference in serum trace metal ions in the revised patients compared with the rest of the patients. (Mann-Whitney U-test; p = 0.2 [cobalt], 0.28 [chromium]).

In 6 patients with new-onset pseudotumors at mid-term followup (Table 4), an increase in serum trace metal ions between early and mid-term followup was noted only in two cases (one both chromium and cobalt and one only chromium). One of these patients went on to have a revision THA for symptomatic pseudotumor (Case 4). In the two cases, in whom a new simple fluid collection was noted but pseudotumor was not conclusively proven (Cases 5 and 6), a drop in serum trace metal ions was noted between early and mid-term followup. The serum chromium level and cobalt level dropped at mid-term followup in both of these cases. Thirty-five asymptomatic patients with normal ultrasound scan findings of their MoM THA were investigated with repeat serum trace metal ions at mid-term followup and these were compared with early followup results (Table 5). A fall in serum trace metal chromium and cobalt metal ions was noted in 11 hips (32%). The remaining patients showed a raise in serum levels at interval followup. Four patients had an increase in serum chromium levels more than 2 μg/L at interval followup (11%). Eight patients were noted to have an increase in serum cobalt levels more than 2 μg/L (23%). Four patients had an increase in both serum chromium and cobalt levels more than 2 μg/L.

Table 5.

PROMs at mid-term followup of patients with persistent pseudotumors

| PROMs | Mean | Range | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford Hip Score | 91 | 79–100 | 9 |

| WOMAC pain | 91 | 75–100 | 10 |

| WOMAC stiffness | 83 | 75–100 | 12 |

| WOMAC function | 90 | 73–100 | 9 |

| WOMAC global | 90 | 75–100 | 8 |

| UCLA | 4 | 1–7 | 2 |

| SF-12 PCS | 51 | 33–57 | 8 |

| SF-12 MCS | 51 | 29–62 | 10 |

PROM = patient-reported outcome measure; PCS = physical component score; MCS = mental component score.

PROMs at mid-term followup of patients with persistent pseudotumors remained high (Table 6). Comparison of global WOMAC scores at early (mean, 93; range, 80–100; SD 6.7) and mid-term followup (mean, 90; range, 75–100; SD 8.25) showed no difference with the numbers available (p = 0.45). PROMs at mid-term followup of patients with new-onset pseudotumors were also noted to be high (Table 7). Only one patient was noted to have a WOMAC score less than 75 (WOMAC 25, Oxford Hip Score 27.08). In the remaining patients, PROMs were noted to be high (mean WOMAC 94, mean Oxford Hip Score 93). Comparison of global WOMAC scores at early (mean, 97; range, 95–100; SD 62.4) and mid-term followup (mean, 94; range, 79–100; SD 8.3) in the patients not revised for pseudotumor showed no difference (p = 0.40).

Table 6.

Metal ions in asymptomatic patients with normal ultrasound scan findings of their MoM THA

| Variable | Early followup | Mid-term followup | Change in serum trace metal ions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cr (μg/L) | Co (μg/L) | Cr (μg/L) | Co (μg/L) | Cr (μg/L) | Co (μg/L) | |

| Mean | 4 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 0.7 | 1 |

| Minimum | 0.38 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | −5 | −11 |

| Maximum | 26 | 22 | 12 | 11 | 17 | 15 |

| SD | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

Negative values indicate fall in serum trace ion levels; MoM = metal-on-metal; Cr = chromium; Co = cobalt.

Table 7.

Ultrasound and serum metal ion findings in patients with new-onset pseudotumor at mid-term followup

| Case number | Early followup | Mid-term Followup | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound (volume in cm3) | Metal ions (μg/L) | Ultrasound (volume in cm3) | Metal ions (μg/L) | |||||

| Finding | Volume | Cr | Co | Finding | Volume | Cr | Co | |

| 1 (PT) | FC | 10 | 1 | 0.7 | CM | 75 | 0.7 | 1 |

| FC | 9 | |||||||

| 2 (PT) | FCa | 59 | 0.8 | 0.5 | CM | 139 | 4 | 9 |

| FCb | 11 | |||||||

| 3 (PT) | None | 1 | 0.9 | CM | 66 | 0.6 | 1 | |

| 4 (PT) | None | – | – | CM | 71 | 4 | 8 | |

| 5 (FC) | None | 8 | 15 | FC | 24 | 7 | 12 | |

| 6 (FC) | None | 2 | 2 | FC | 14 | 2 | 2 | |

Cr = chromium; Co = cobalt; PT = pseudotumor; SM = solid mass; CM = cystic mass; FC = fluid collection; where the ultrasound showed more than one collection, their volumes were separately measured and documented as a, b, c, etc.

PROMs were available in 30 of the 35 asymptomatic patients (Table 8). The eight patients with an increase in serum cobalt and chromium levels of more than 2 μg/L at interval followup had high PROM scores (WOMAC global 91; range, 77–100; SD 10.57; Oxford Hip Score 92; range, 79–100; SD 9.08; UCLA 3.71; range, 2–5; SD 1.38).

Table 8.

PROMs in asymptomatic patients with normal ultrasound scan findings of their MoM THA

| PROMs | Mean | Range | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford Hip Score | 92 | 46–100 | 14 |

| WOMAC pain | 90 | 45–100 | 16 |

| WOMAC stiffness | 88 | 38–100 | 19 |

| WOMAC function | 92 | 42–100 | 14 |

| WOMAC global | 91 | 45–100 | 14 |

| UCLA | 4 | 1–7 | 2 |

| SF-12 PCS | 49 | 23–60 | 10 |

| SF-12 MCS | 55 | 30–63 | 9 |

PROM = patient-reported outcome measure; MoM = metal-on-metal; PCS = physical component score; MCS = mental component score.

Discussion

The routine use of MoM THA is currently discouraged as a result of concerns regarding elevated serum metal ions and their local and systemic side effects. The natural history of asymptomatic pseudotumors at mid-term followup in patients with MoM THA is not well known. Our study shows that half of the pseudotumors diagnosed in asymptomatic individuals at early followup remain asymptomatic at interval followup. Approximately one-third showed an increase in volume; however, in some of these, the increase in volume was small. Eleven percent (eight of 71 patients) of MoM THAs or 36% (eight of 23 positive scans) of early positive ultrasound scans culminate in revision THA. A small percentage of patients (9% or two of 23 positive scans) showed complete resolution of any fluid or cystic lesions at interval ultrasound. Eight percent of previously normal scans showed new changes conclusively diagnosed as pseudotumor.

Our study had some drawbacks. Two patients were lost to followup. Three patients were asymptomatic and refused further investigations. Our study had modest numbers (71 patients). Despite this we believe that the study group was representative and the results could be extrapolated to clinical practice. We used only ultrasound to diagnose pseudotumor and this is the routine practice at our institution. We have previously published on high diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound scans to diagnose pseudotumors [12]. In the cases that developed new fluid collections at mid-term followup, we did not further investigate them with MRI or image-guided biopsy. Because patients were asymptomatic, we choose to continue clinical followup and repeat the ultrasound investigations. We also chose our cohort from two previously published studies [12, 27]. This was necessary to ensure that the patients chosen for this study were all investigated for pseudotumors with ultrasound scans at early followup. Data presented in those studies have been used for comparison with the mid-term results presented here.

Two recently published studies have investigated pseudotumors in MoM THA. van der Veen et al. [24] compared the incidence of pseudotumors after large-head (38–60 mm) MoM THA (41 hips) with that after conventional 28-mm head metal-on-polyethylene (MoP) THA (55 hips) at mid-term followup. They observed an overall incidence of 22 (54%) pseudotumors in MoM THAs compared with 12 (21.8%) in MoP THAs at medium-term followup (50 months; range, 30–64 months). An increased risk of pseudotumor development was noted in females with a large-head MoM THA. Fehring et al. [11] investigated 114 patients to determine the prevalence of adverse local tissue reaction (ALTR) in asymptomatic patients with modular MoM THAs. They reported ALTR in 31% of asymptomatic patients with modular MoM THAs and in 50% of symptomatic patients with modular MoM THAs. There were no differences in the type of lesions between the two groups, both having a majority of cystic lesions. Although all asymptomatic patients had greater trochanteric lesions, approximately one-third of the symptomatic group had lesions noted in other periarticular areas. Our study looked at a cohort of patients with well-functioning MoM THA and followed them prospectively to establish the early and intermediate incidence of pseudotumors and the associated change in PROMs and serum metal ions. The frequency of new pseudotumors between early and intermediate followup in our series was much lower at 8% (four new pseudotumors in previously negative 48 scans). Our study noted both cystic and solid pseudotumors in the asymptomatic patients. The incidence of revision THA after the diagnosis of early pseudotumors in our series was 35%. There was one revision in the cohort of patients who had a delayed onset pseudotumor at mid-term followup. The grade/type/size of pseudotumor was not predictive of revision for pseudotumor.

van der Veen et al. [24] noted elevated serum cobalt levels were also found more often with MoM THA than with MoP THA. Interestingly, there was no relationship between elevated serum cobalt levels and pseudotumor formation in males. Fehring et al. [11] noted that metal ions were poor predictors of pseudotumors. Our study showed that in cases in which the pseudotumor increased in size between early and mid-term followup, the serum trace metal ions also showed an increase. However, this relationship was not mirrored when pseudotumors stayed the same or decreased in size. Also those patients undergoing revision did not show a statistically significant difference in their serum trace metal ions compared with those not undergoing revision.

Our study reviewed the PROMs in asymptomatic pseudotumors at mid-term followup. This has not been investigated by other studies to our knowledge. Overall the PROMs were noted to be high. Persistent pseudotumors were not associated with a decrease in outcome scores. A drop in PROM score did not necessarily reflect new-onset pseudotumors. However, the one patient who went on to have revision THA after new-onset pseudotumor at mid-term follow up had decreased PROMs (WOMAC < 75 and Oxford Hip Score < 25) before revision.

In conclusion, patients with early pseudotumors undergoing revision as a result of symptomatic deterioration in the hip show poor correlation with metal ions. However, a solid or cystic pseudotumor was associated with all revisions.

Surveillance is necessary given the new onset of pseudotumors noted at mid-term followup in this series. Based on our results we would recommend clinical followup with interval imaging as the ideal followup in asymptomatic MoM THA. Long-term followup studies will establish the progression of pseudotumors that develop at early and mid-term followup.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nelson V. Greidanus MD, MPH, for contributing patients to the study; Shelley James (Canada Diagnostics, Vancouver) for performing the ultrasound scans; Eric C. Sayre PhD, for his help with the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® neither advocates nor endorses the use of any treatment, drug, or device. Readers are encouraged to always seek additional information, including FDA-approval status, of any drug or device prior to clinical use.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-5032-8.

References

- 1.Almousa SA, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP, Garbuz DS. The natural history of inflammatory pseudotumors in asymptomatic patients after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:3814–3821. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2944-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaule PE, Kim PR, Hamdi A, Fazekas A. A prospective metal ion study of large-head metal-on-metal bearing: a matched-pair analysis of hip resurfacing versus total hip replacement. Orthop Clin North Am. 2011;2:251–257, ix. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Boardman DR, Middleton FR, Kavanagh TG. A benign psoas mass following metal-on-metal resurfacing of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;3:402–404. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B3.16748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clayton RA, Beggs I, Salter DM, Grant MH, Patton JT, Porter DE. Inflammatory pseudotumor associated with femoral nerve palsy following metal-on-metal resurfacing of the hip. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;9:1988–1993. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Counsell A, Heasley R, Arumilli B, Paul A. A groin mass caused by metal particle debris after hip resurfacing. Acta Orthop Belg. 2008;6:870–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuckler JM, Moore KD, Lombardi AV, Jr, McPherson E, Emerson R. Large versus small femoral heads in metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2004;8(Suppl 3):41–44. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniel J, Pynsent PB, McMinn DJ. Metal-on-metal resurfacing of the hip in patients under the age of 55 years with osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;2:177–184. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B2.14600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies AP, Willert HG, Campbell PA, Learmonth ID, Case CP. An unusual lymphocytic perivascular infiltration in tissues around contemporary metal-on-metal joint replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;1:18–27. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.00949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowson D, Hardaker C, Flett M, Isaac GH. A hip joint simulator study of the performance of metal-on-metal joints: Part II: design. J Arthroplasty. 2004;8(Suppl 3):124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunstan E, Ladon D, Whittingham-Jones P, Carrington R, Briggs TW. Chromosomal aberrations in the peripheral blood of patients with metal-on-metal hip bearings. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;3:517–522. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fehring TK, Odum S, Sproul R, Weathersbee J. High frequency of adverse local tissue reactions in asymptomatic patients with metal-on-metal THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:517–522. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3222-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garbuz DS, Tanzer M, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP. The John Charnley Award: Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing versus large-diameter head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:318–325. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1029-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gruber FW, Bock A, Trattnig S, Lintner F, Ritschl P. Cystic lesion of the groin due to metallosis: a rare long-term complication of metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;6:923–927. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart AJ, Satchithananda K, Liddle AD, Sabah SA, McRobbie D, Henckel J, Cobb JP, Skinner JA, Mitchell AW. Pseudotumors in association with well-functioning metal-on-metal hip prostheses: a case-control study using three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;4:317–325. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim PR, Beaule PE, Dunbar M, Lee JK, Birkett N, Turner MC, Yenugadhati N, Armstrong V, Krewski D. Cobalt and chromium levels in blood and urine following hip resurfacing arthroplasty with the conserve plus implant. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011:107–117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Kwon YM, Ostlere SJ, McLardy-Smith P, Athanasou NA, Gill HS, Murray DW. ‘Asymptomatic’ pseudotumors after metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty: prevalence and metal ion study. J Arthroplasty. 2011;4:511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lavigne M, Ganapathi M, Mottard S, Girard J, Vendittoli PA. Range of motion of large head total hip arthroplasty is greater than 28 mm total hip arthroplasty or hip resurfacing. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2011;3:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Mao X, Wong AA, Crawford RW. Cobalt toxicity–an emerging clinical problem in patients with metal-on-metal hip prostheses? Med J Aust. 2011;12:649–651. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray DW, Grammatopoulos G, Gundle R, Gibbons CL, Whitwell D, Taylor A, Glyn-Jones S, Pandit HG, Ostlere S, Gill HS, Athanasou N, McLardy-Smith P. Hip resurfacing and pseudotumour. Hip Int. 2011;3:279–283. doi: 10.5301/HIP.2011.8405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL, Ostlere S, Athanasou N, Gill HS, Murray DW. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;7:847–851. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters CL, McPherson E, Jackson JD, Erickson JA. Reduction in early dislocation rate with large-diameter femoral heads in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;6(Suppl 2):140–144. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuchin SA. Anatomic diameter femoral heads in total hip arthroplasty: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(Suppl 3):52–56. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tower SS. Arthroprosthetic cobaltism: neurological and cardiac manifestations in two patients with metal-on-metal arthroplasty: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;17:2847–2851. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Veen HC, Reininga IH, Zijlstra WP, Boomsma MF, Bulstra SK, van Raay JJ. Pseudotumour incidence, cobalt levels and clinical outcome after large head metal-on-metal and conventional metal-on-polyethylene total hip arthroplasty: mid-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J. 2015;11:1481–1487. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B11.34541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Weegen W, Smolders JM, Sijbesma T, Hoekstra HJ, Brakel K, van Susante JL. High incidence of pseudotumours after hip resurfacing even in low risk patients; results from an intensified MRI screening protocol. Hip Int. 2013;3:243–249. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vendittoli PA, Amzica T, Roy AG, Lusignan D, Girard J, Lavigne M. Metal ion release with large-diameter metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;2:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams DH, Greidanus NV, Masri BA, Duncan CP, Garbuz DS. Prevalence of pseudotumor in asymptomatic patients after metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;23:2164–2171. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]