Abstract

Many prospective studies and a recent randomized controlled trial have shown that the B-cell depleting monoclonal antibody rituximab safely promotes remission of nephrotic syndrome in approximately 65% of patients with membranous nephropathy (MN). Mechanistic studies have indicated that rituximab-induced proteinuria reduction is associated with clearance of anti-PLA2R autoantibodies and subepithelial immune complexes, the hallmarks of the disease. A recently published study reported results which, at first sight, looked less favorable and implied that, due to a publication bias against negative results, the efficacy of rituximab in MN might be overestimated. Since patients received only one or two rituximab administrations, the authors suggest that when rituximab is used, higher doses and longer treatments should be considered. Herein, we highlight limitations of the study and warn against an oversimplified interpretation of the data. Though information on the optimal dose of rituximab to use in MN is still limited, available data from studies with predefined rituximab administration protocols collectively support the concept of titrating rituximab to the number of circulating B-cells that are invariably depleted after the first or second administration. Additional doses may increase the risk of adverse effects and related costs without augmenting efficacy. Importantly, underpowered studies with inconclusive results should not be confused with negative studies formally proving a neutral effect of a treatment. Until data from ad hoc designed clinical trials are available, the B-cell driven protocol should the preferred regimen, since it is similarly effective, but safer and more cost-saving than other protocols employing multiple rituximab administrations.

Keywords: membranous nephropathy, nephrotic syndrome, negative study, rituximab

The 2001 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines suggest the use of alkylating agents plus steroids as first-line therapy for membranous nephropathy (MN), while calcineurin inhibitors, either alone or in combination with steroids, are recommended for patients who do not tolerate or refuse alkylating agents [1]. These indications are largely based on studies performed in the 1980s and 1990s, when disease pathogenesis was only partially understood and treatment options were limited. Better understanding of disease mechanisms, including the identification of the main target podocyte antigens phospholipase 2 receptor (PLA2R) [2] and thrombospondin type-1 domain containing 7A (THSD7A) [3], together with the development of new, more selective and less toxic immunosuppressive agents, has allowed the development of hypothesis-driven therapies [4].

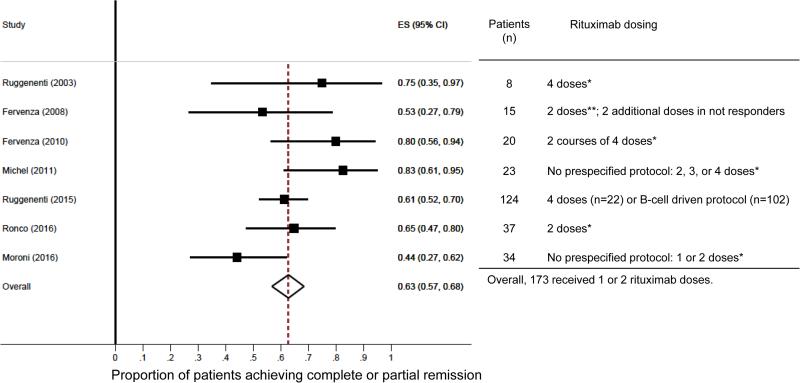

Evidence that B cells play a central pathogenic role in MN, both as antigen presenting cells [5] and as autoantibody producing cells [4], provided the background for explorative studies testing the role of B cell-depletion therapy with the monoclonal antibody rituximab. The first report in 2002 showing that rituximab safely ameliorated nephrotic syndrome (NS) in 8 patients with primary MN [6] fueled a series of observational studies that uniformly confirmed the excellent safety/efficacy profile of rituximab in this glomerular disease. Evidence accumulated so far from prospective studies [7-9], including a series of 100 consecutive patients [10], collectively indicates that rituximab therapy safely induces complete or partial remission in approximately 65% of MN patients with NS (Figure). Proteinuria remission generally occurs within one year after therapy, even though late responses have been observed as well. Response to therapy is similar between patients who receive rituximab as first-line therapy or as a rescue treatment after other treatments have failed [11]. Importantly, mechanistic studies have shown that rituximab-induced depletion of circulating B cells is followed by a decline in anti-PLA2R antibodies that invariably anticipates a decline in proteinuria [12, 13]. These data, along with the finding observed in patients with repeated renal biopsies that rituximab-induced proteinuria remission is associated with the disappearance of subepithelial immune complexes [14], the hallmark of MN indicate that rituximab targets a crucial pathogenic mechanism of the disease.

Figure.

Forest plot of the proportion of remission with rituximab after 12-24 months (left) and table reporting numbers of patients included in the studies and rituximab dosing (right). The estimated proportions and their 95% confidence intervals were calculated with a random-effects model using the method of DerSimonian and Laird. The 8 patients included in the series by Ruggenenti et al. and reported in 2013 were removed from the 132 patients reported by the same group in 2015.

Even though the forest plot displays equal weights for the individual studies, weighting was indeed done using an iterative procedure. The dashed vertical line represents the overall estimate. Studies not crossing the vertical dashed line are significantly different from the overall average. ES, estimated proportion; CI, confidence interval. Rituximab doses: *375mg/m2; **1g.

Recently, the randomized-controlled Evaluate Rituximab Treatment for Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy (GEMRITUX) trial randomized 75 MN patients with NS to rituximab (two 375/mg/m2 doses) versus no immunosuppression and evaluated the rate of complete or partial remission at 6 months after therapy (primary endpoint) [15]. Although the study failed in detecting a significant difference between the two groups in the primary 6-mont endpoint (35% vs. 21% in rituximab-treated vs. control patients; P 0.21), after an extended median follow-up of 17 months, 64.9% of rituximab-treated patients versus 34.2% of the untreated subjects achieved remission (P<0.01). Treatment was very well tolerated.

Altogether, these results appear similar or even superior to those reported in trials testing the efficacy of alkylating agents and steroids both in terms of remission rates and time to remission. Despite similar efficacy, however, rituximab therapy is devoid of the serious toxicities of such therapies. Therefore, within the limitations of comparisons across different studies, available data suggest that rituximab is at least as effective as alkylating agents plus steroids, but is associated with fewer adverse events [16].

A recent prospective cohort study by Moroni et al. reported less favorable results [17]. These authors evaluated the rate of partial and complete remission after one or two rituximab administrations (375mg/m2 each) in 34 patients with MN and NS. No predefined protocol to decide on single or dual rituximab administration is provided. At 6 months after therapy, 15 patients (44%) achieved remission, which is consistent with the data reported in the GEMRITUX trial [15], but, in contrast to the GEMRITX trial, no additional patient achieved remission between 6 and 12 months after therapy. There was no difference in response between patients who received one or two rituximab doses, nor between patients who received rituximab as first-line or second-line therapy. Only 24 (70%) of the initial cohort of patients had a follow-up longer than 12 months. Among these patients, 13 (54%) reached remission at one year after treatment (two had a relapse of proteinuria), which is below what has been previously reported in larger studies with predefined rituximab administration protocols (Figure). The authors ascribed this result to the lower than commonly used doses of rituximab.

The issue of optimal rituximab dosing in MN is still matter of debate. Rituximab doses used across the various studies in MN patients differ significantly, ranging from a single dose of 375mg/m2 to a repeated course of four 375mg/m2 weekly doses 6 months apart. The initially used 4-dose regimen was adopted from rituximab dosing in Hodgkin's lymphoma, the only indication for rituximab therapy at that time [18]. However, as the number of CD20 cells in patients with MN is significantly lower than in patients with lymphoproliferative diseases, the need for anti CD20 antibody to induce a complete lymphocyte depletion might be consequently lower, consistent with the evidence that CD20+ B cells are fully depleted from the circulation after the first rituximab administration in patients with MN or lupus. To address this issue, a prospective, matched-cohort study compared the safety/efficacy profile of a B cell-driven rituximab treatment with the standard four 375mg/m2 dose protocol in 36 MN patients with long-lasting nephrotic range proteinuria refractory to conventional therapy [19]. Patients allocated to the B cell-driven protocol received a second infusion only if they had more than five B cells/mm3 of peripheral blood after the first rituximab administration, which occurred in only 1 of the 12 patients in this group. Prompt and persistent B cell depletion was achieved in all patients. Time-dependent changes in proteinuria and the other components of NS were similar in the two groups, but the B cell-driven approach was associated with fewer adverse events and less hospitalizations, and was fourfold less expensive. These findings were confirmed by a large prospective cohort study including 100 MN patients showing that a B-cell driven rituximab protocol provides similar efficacy than the 4-dose regimen [10]. Thus, B cell titrated dosing, seems as effective as a four-dose regimen, but is safer and cost-saving. Due to the excellent relationship between the levels of circulating anti-PLA2R antibodies and disease activity, this biomarker could be tested in the future as an alternative tool to titrate rituximab therapy [12].

Consistent with the aforementioned reports, the study by Moroni et al. showed that B cells were fully depleted in all the patients, regardless from the use of single or repeated rituximab administrations. Unfortunately, lack of serial B cell measurements prevents any comparison in B cell recovery between the two rituximab treatment regimens. Moreover, the absence of a control group of subjects receiving a 4-dose treatment precludes any conclusion on the impact of rituximab dosing on the proteinuria reduction.

Importantly, previous data have clearly indicated that patients with tubulointerstitial lesions at renal biopsy and impaired renal function have milder and slower response than patients with normal renal function [20]. Since about one third of patients enrolled in the study by Moroni et al. had an eGFR<60ml/min/m2, a longer follow-up period would have been important to adequately detect the rituximab effect. Lack of serial measurements of anti-PLA2R antibodies also prevents a full understanding of rituximab efficacy in this cohort of patients. Despite these limitations, the authors conclude that “since negative studies are seldom reported, the efficacy of rituximab in membranous nephropathy might be overestimated”.

The issue of publication bias against negative findings is of course very important. Statistically significant results are more likely to be published than papers with null results [21]. This bias may seriously distort the literature, drain scarce resources by undertaking research in futile quests, and lead to misguided research and clinical practices. However, the risk of publication bias may change direction over time. The publication cycle also clearly illustrates that significant findings are published ahead of nonsignificant findings, and that significant findings seem to provide an incentive to publish nonsignificant studies [22]. Since studies have extensively shown that rituximab safely promotes remission in approximately 65% of patients with MN, there may be now the risk of a publication bias favoring unexpected negative results, which is of course as worrisome as the opposite bias.

More importantly, similar to studies with positive results, negative studies can be conclusive, exploratory, or inconclusive, based on their design and statistical power [23]. Is the report by Moroni et al. a true negative study or just an inconclusive collection of clinical data? Unfortunately, lack of a formal protocol or rationale for the choice of the rituximab doses, absence of sample size estimation and a follow-up inadequate to the already available knowledge on the timing for rituximab response, make this study far from being a conclusive one.

The evidence supporting the use of rituximab in the treatment of MN represents a valuable advancement in new therapies also for other glomerulopathies. Experimental studies investigating disease pathogenesis provided the background for this hypothesis-driven approach that, due to its selective mechanism of action, allowed further understanding of disease mechanisms. Data from small, mechanistic clinical studies led to the GEMRITUX trial and the currently ongoing larger trials (NCT01955187, NCT01180036) that, altogether, will formally define the place of rituximab in the treatment of MN. At the present time, even considering data from Moroni et al., the response rate to rituximab is 65% (Figure), which is similar to what has been previously reported with more toxic treatments such as alkylating agents [24]. Importantly, published studies on rituximab therapy employed, in the vast majority of cases, doses similar to the ones employed by Moroni et al. However, the impact of different reports on the therapeutic decisions should always be grounded on critical appraisal of the quality of the study. Only a randomized controlled trial will definitively answer the question about the optimal dose of rituximab to use in MN. Based on available data, since no evidence supports a relationship between rituximab dose and efficacy in promoting proteinuria remission, while higher doses associate with more adverse events and costs, the B-cell driven regimen should be the approach employed in everyday clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

PC is supported by NIH T32 training grant 5T32AI078892-07.

References

- 1.Radhakrishnan J, Cattran DC. The KDIGO practice guideline on glomerulonephritis: reading between the (guide)lines--application to the individual patient. Kidney Int. 2012;82:840–56. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.280. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beck LH, Jr., Bonegio RG, Lambeau G, Beck DM, Powell DW, Cummins TD, et al. M-type phospholipase A2 receptor as target antigen in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomas NM, Beck LH, Jr., Meyer-Schwesinger C, Seitz-Polski B, Ma H, Zahner G, et al. Thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing 7A in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2277–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409354. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ronco P, Debiec H. Pathophysiological advances in membranous nephropathy: time for a shift in patient's care. Lancet. 2015;385:1983–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60731-0. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60731-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen CD, Calvaresi N, Armelloni S, Schmid H, Henger A, Ott U, et al. CD20-positive infiltrates in human membranous glomerulonephritis. J Nephrol. 2005;18:328–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remuzzi G, Chiurchiu C, Abbate M, Brusegan V, Bontempelli M, Ruggenenti P. Rituximab for idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Lancet. 2002;360:923–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck LH, Jr., Fervenza FC, Beck DM, Bonegio RG, Malik FA, Erickson SB, et al. Rituximab-Induced Depletion of Anti-PLA2R Autoantibodies Predicts Response in Membranous Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1543–50. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010111125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bomback AS, Derebail VK, McGregor JG, Kshirsagar AV, Falk RJ, Nachman PH. Rituximab therapy for membranous nephropathy: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:734–44. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05231008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fervenza FC, Abraham RS, Erickson SB, Irazabal MV, Eirin A, Specks U, et al. Rituximab therapy in idiopathic membranous nephropathy: a 2-year study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2188–98. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05080610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruggenenti P, Cravedi P, Chianca A, Perna A, Ruggiero B, Gaspari F, et al. Rituximab in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1416–25. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012020181. Epub 2012/07/24. doi: ASN.2012020181 [pii] 10.1681/ASN.2012020181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cravedi P, Sghirlanzoni MC, Marasa M, Salerno A, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P. Efficacy and safety of rituximab second-line therapy for membranous nephropathy: a prospective, matched-cohort study. Am J Nephrol. 2011;33:461–8. doi: 10.1159/000327611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruggenenti P, Debiec H, Ruggiero B, Chianca A, Pelle T, Gaspari F, et al. Anti-Phospholipase A2 Receptor Antibody Titer Predicts Post-Rituximab Outcome of Membranous Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2545–58. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070640. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck L, Fervenza F, Beck D, Bonegio R, Erickson SB, Cosio FG, et al. Anti-PLA2R autoantibodies and response to rituximab treatment in membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010111125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggenenti P, Cravedi P, Sghirlanzoni MC, Gagliardini E, Conti S, Gaspari F, et al. Effects of rituximab on morphofunctional abnormalities of membranous glomerulopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1652–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01730408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahan K, Debiec H, Plaisier E, Cachanado M, Rousseau A, Wakselman L, et al. Rituximab for Severe Membranous Nephropathy: A 6-Month Trial with Extended Follow-Up. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016040449. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016040449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cravedi P, Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P. Rituximab in primary membranous nephropathy: first-line therapy, why not? Nephron Clin Pract. 2014;128:261–9. doi: 10.1159/000368589. doi: 10.1159/000368589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moroni G, Depetri F, Del Vecchio L, Gallelli B, Raffiotta F, Giglio E, et al. Low-dose rituximab is poorly effective in patients with primary membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw251. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruggenenti P, Cravedi P, Remuzzi G. Rituximab for membranous nephropathy and immune disease: less might be enough. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2009;5:76–7. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph1007. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cravedi P, Ruggenenti P, Sghirlanzoni MC, Remuzzi G. Titrating rituximab to circulating B cells to optimize lymphocytolytic therapy in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:932–7. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01180307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruggenenti P, Chiurchiu C, Abbate M, Perna A, Cravedi P, Bontempelli M, et al. Rituximab for idiopathic membranous nephropathy: who can benefit? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:738–48. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01080905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:252–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065779. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa065779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luijendijk HJ, Koolman X. The incentive to publish negative studies: how beta-blockers and depression got stuck in the publication cycle. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:488–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.022. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joober R, Schmitz N, Annable L, Boksa P. Publication bias: what are the challenges and can they be overcome? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37:149–52. doi: 10.1503/jpn.120065. doi: 10.1503/jpn.120065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ponticelli C, Zucchelli P, Passerini P, Cesana B. Methylprednisolone plus chlorambucil as compared with methylprednisolone alone for the treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy. The Italian Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy Treatment Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:599–603. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208273270904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]