Abstract

During the twentieth century, trends in childlessness varied strongly across European countries while educational attainment grew continuously across them. Using census and large-scale survey data from 13 European countries, we investigated the relationship between these two factors among women born between 1916 and 1965. Up to the 1940 birth cohort, the share of women childless at age 40+ decreased universally. Afterwards, the trends diverged across countries. The results suggest that the overall trends were related mainly to changing rates of childlessness within educational groups and only marginally to changes in the educational composition of the population. Over time, childlessness levels of the medium-educated and high-educated became closer to those of the low-educated, but the difference in level between the two better educated groups remained stable in Western and Southern Europe and increased slightly in the East.

Keywords: childlessness, cohort fertility, education trends, Eastern Europe, Western Europe

1. Introduction

Of the fundamental changes to women’s lives that brought change to national fertility levels in the twentieth century, primary importance has been assigned to growing educational attainment and labour force participation, together with effective fertility control (Murphy 1993; Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; Bianchi and Milkie 2010). One key component of fertility change during the century was the change in the proportion childless. Undoubtedly, in the first half of the century, this proportion was largely determined by the wars, the great economic depression, and the persistently poor health conditions, and in the later period both by new life aspirations and hormonal contraception (Kreager 2004; Rowland 2007; Tanturri and Mencarini 2008; Van Bavel and Reher 2013; Tanturri et al. 2015). In the study reported in this paper, we investigated whether rising educational attainment was another factor that contributed to the share of women who remained permanently childless.

Among European women born in the twentieth century, permanent childlessness varied greatly across time and regions. It declined universally until the 1940s birth cohorts, when it tended to stabilize in the state-socialist countries and to rise again in the West (Frejka and Sardon 2004; Van Agtmaal-Wobma and van Huis 2008; Sobotka 2012; Miettinen et al. 2015; Reher and Requena 2015). In contrast, enrolment of females in education went up continuously across all of Europe, starting in the first half of the century (Goujon 2009; Breen et al. 2010; Barro and Lee 2013). An increasing number of women gained secondary education, eventually outnumbering those with basic or no education. University education also became increasingly popular, but at a slower pace. Among the questions we wished to pursue were the following. Did the prevalence of childlessness change across all educational strata over the century? Since childlessness tended to be educationally stratified (Miettinen et al. 2015; Van Bavel et al. 2015), did the expansion of the medium- and high-educated groups affect the overall percentage of childless women, as well as the share of women remaining childless within educational groups?

Studies of trends in childlessness that take education into account have mostly confined their analyses either to those born during the baby boom that followed the Second World War or to a specific region or country (Köppen et al. 2007; Van Agtmaal-Wobma and van Huis 2008; Andersson et al. 2009; Van Bavel 2014). There has not previously been a European overview of changes over a long time span that would help explain the observed diversity in childlessness. This paper reports such a study. Using data from censuses and large-scale surveys from 13 European countries, the study investigated the macro-level relationship between education and ultimate childlessness and its variation across the 1916–65 birth cohorts (which correspond to the period between the 1940s and early 2000s). By choosing this time span we covered both the early period of universal decline in the proportion of childless women and the later diversification across regions. We compared countries from both the West and the state-socialist parts of Europe. The study yields a unique portrait of trends in childlessness and education, and their interplay on the long-divided continent.

2. Childlessness and education

2.1. Trends in childlessness and education

Several studies have documented cross-country trends in childlessness in the twentieth century (Sardon 2002; Rowland 2007; Frejka 2008). Cohorts of women born at the beginning of the century had a strikingly high prevalence of childlessness, despite the absence of effective birth control at that time (Morgan 1991). In Northern and Western Europe, and in Italy, up to 25–30 per cent of women remained childless, as did over 20 per cent in the Czech Republic, Romania, and Hungary (Rowland 2007; Frejka 2008). Among cohorts born later in the century, the percentage childless decreased steeply until around the 1940 birth cohort, in both Western and state-socialist Europe. During the baby boom, that is, the time of universal (and early) marriage and childbearing, they went down to between 10–15 per cent in the former and 5–10 per cent in the latter. Differences in the trends then began to emerge between capitalist and state-socialist countries. In the former, childlessness started to rise again quickly, varying in the 1960 birth cohort from 10 per cent in Greece and Spain to 20 per cent in Germany (Sobotka 2012; Miettinen et al. 2015). In the state-socialist countries, childlessness usually continued to decline until levelling off and oscillating around 6–8 per cent between the 1950s and the early 1960s birth cohorts, and then began to increase at a varied pace (Frejka 2008).

The trends described above were accompanied by a massive expansion of secondary education. The proportion of women finishing their education at primary level shrank continuously. By the 1950s birth cohorts more than half of women had at least secondary education in most European countries (Breen et al. 2010). The medium-educated were the largest educational group, and their fertility had become a driving element of overall fertility levels by the end of the twentieth century (Kreyenfeld and Konietzka 2008). In a parallel development, high education spread continuously as well, but rather slowly. In most countries the share of university degree holders among women born at the beginning of the 1960s did not exceed 20 per cent (Breen et al. 2010; OECD 2014).

2.2. Educational gradient in childlessness in Europe and the US

The high levels of childlessness observed between the second half of the nineteenth century and the 1940s occurred in all social strata, but they were particularly elevated among highly educated women active in the labour market (Van Bavel et al. 2015). The reasons for a positive educational gradient in childlessness seem to have been similar to those found today (see Dykstra and Hagestad 2007). High-resource women appeared reluctant to enter marriage with a gender-based division of roles, and might have been unattractive in the marriage market where men were usually looking for housewives rather than independent female partners. The elites tended to postpone marriage and childbearing within marriage (and postponement often led to childlessness) because of the increasing demands that they had been instrumental in imposing on the role of parents and the high costs of children’s education (Pooley 2013), and because of the recreational opportunities and luxuries offered by life without the burden of children (Van Bavel and Kok 2010).

For the recent period, researchers generally expect a positive aggregate relationship between level of education and cohort childlessness, in line with the strong evidence of a negative association between transition to first birth and education at the individual level (Bloom and Trussell 1984; González and Jurado-Guerrero 2007; Nicoletti and Tanturri 2008). According to the New Household Economics (Becker 1981), the opportunity cost of raising children is greater for higher-income women (who usually also have higher-than-average levels of education), which would make them more likely to forgo motherhood. The changes in norms and values of the second demographic transition, including the rise of feminism and individualism, have led to the development of the concept of ‘childfree’ lives (Letherby 2002), mainly embraced by specific social groups like highly educated and high-income women (González and Jurado-Guerrero 2007; Tanturri and Mencarini 2008). In addition, because the early adulthood of better educated women is devoted to schooling and then building a career, highly educated women are more likely to become ‘perpetual postponers’ (Berrington 2004), and to reach the end of reproductive life without having a child. Thus, the highly educated seem likely to be more exposed than the less educated to both ‘voluntary’ and ‘involuntary’ childlessness (Bulcroft and Teachman 2004). Finally, if less family-oriented women acquire more education (Hakim 2003), this selection effect would inflate the positive relationship between education and childlessness, by increasing the share of women with low education and children.

A positive educational gradient in childlessness has become established in the UK and the US (Kneale and Joshi 2008; Hayford 2013; Berrington et al. 2015) and in the German-speaking countries except East Germany before and after unification (Sobotka 2012). Also in France women with high education are less likely to have children than those with low education (Köppen et al. 2007; Masson 2013). However, evidence from Northern Europe shows that the gradient can change over time and can vary in steepness (Andersson et al. 2009). For instance, the gradient is much more pronounced in Norway than in Denmark. In the latter, there was no difference in the proportion childless between the low-educated and medium-educated born in the 1950s birth cohorts. In the 1955–59 birth cohort in Finland and Sweden, the education–childlessness relationship shows a U-shape, with the medium-educated exhibiting the lowest level of childlessness and the low-educated the highest (Andersson et al. 2009). One study found that childlessness can be reduced by policy measures that make it easier for women to combine motherhood with participation in the labour force (González and Jurado-Guerrero 2007). Such measures could lead to a smaller positive or even a negative educational gradient in childlessness. Finally, for countries participating in the Generations and Gender Programme, Wood et al. (2014) showed that the educational gradient in childlessness was very weak in Belgium, Russia, Hungary, and Estonia. They also found that despite the large educational changes, the shape of the gradient between low, medium, and high education was very stable between the 1940–44 and the 1956–61 birth cohorts in each of those countries. The Results section of the paper presents a comprehensive description of the variation in educational differences in permanent childlessness across cohorts born in the twentieth century and in countries in the East and West of Europe.

2.3. Compositional change in education and childlessness

The expansion of education among women could have affected childlessness levels in various ways. If educational differences in childlessness had remained constant over time (in other words, if women in all educational groups had retained their childlessness rates relative to the rates of the other groups), the overall level of childlessness would have been directly influenced by the educational composition of the population. It is, however, also possible that changes in the behaviour of women within each educational group altered the educational gradient. For example, as education levels rose rapidly, the group of medium-educated women might have absorbed individuals with less educated backgrounds, together with their values and lifestyles. Previous research has documented intergenerational transmission of fertility preferences by the passing on of parents’ ideals to children (Preston 1976; Anderton et al. 1987; Kolk 2014). According to the acculturation hypothesis, which was supported by the research of Blau and Duncan (1967), and then by Sobel’s (1981, 1985) studies, those who achieve a higher socio-economic status than that of their parents will only partially conform to the norms and values of their new stratum, including those concerning family formation. If this mechanism holds here, levels of childlessness among the medium-educated could have become more similar to those seen among the least educated as the former group expanded.

Another example was the change among highly educated women during the baby boom after the Second World War. Because they changed their childbearing behaviour and had more children, the fact that they became a higher proportion of the population did not result in lower overall fertility (Reher and Requena 2014; Sandström 2014; Van Bavel 2014). When the proportion of highly educated women was very small, university graduates were a highly selected group of women, most from families with substantial intellectual and economic resources. As those with less education received the further education that made them eligible to join the highly educated, the latter group slowly expanded and lost some of its distinctiveness (Goldin 2004). The spread of higher education could thus have resulted in lower levels of childlessness in this group. At the same time, childlessness could also have started to become more popular among the dwindling proportion of women with low education.

Our analysis of the compositional change in the population of females and the contribution of the various educational groups to the overall level of childlessness has helped to disentangle their role in the fluctuating childlessness rates over the century. We examined the largely unexplored developments in childlessness and education of females by addressing two questions. First, have the levels of childlessness among women with medium and low education become more similar with time? Second, did childlessness among highly educated women lose its distinctiveness as that group became less select?

2.4. Childlessness in the East and in the West

As pointed out above, women born at the turn of the twentieth century quite often stayed childless. This was partly because of the high age at marriage and generally low marriage rates, but also because of delayed childbearing even among married women, often attributed to the wars and economic circumstances (Morgan 1991; Rowland 2007). Historical studies found that postponing marriage and delaying childbearing within marriage were often socially accepted strategies at times of economic pressure (Rowland 2007). The great losses of men in the First World War and the dramatic economic situation during the Great Depression caused many women to postpone or forgo marriage and motherhood (Rindfuss et al. 1988; Morgan 1991). For France and the US, it has been estimated that around 16.5 and 20 per cent, respectively, of ever-married women born in the 1900s remained childless (Morgan 1991; Toulemon 1996).

Studies of family formation in the past were mostly of the Western countries since relevant data on behaviour in Eastern Europe have been scarce and confined to small communities scattered across the region (see Szołtysek 2012 for a discussion of the consequences of the missing data on this region). Contrary to common belief (fostered by concepts like the Hajnal line), it seems that before the continent was divided into Western and state-socialist blocs, Eastern Europe did not have a uniform culture (Szołtysek and Zuber-Goldstein 2009). The region did not have a particular family system that differed from the system in the West. Rather, family norms and structures seemed to be largely determined by socio-economic factors (Sovic 2008). Therefore, we have no reason to believe that under similar socio-economic circumstances, family norms—in particular those regarding the acceptance of childlessness—in the East differed substantially from those in the West. Indeed, childlessness levels for women born at the beginning of the twentieth century in the Czech Republic and Romania went beyond 20 per cent, similarly to those in Western countries (Frejka 2008).

The end of the Second World War brought socio-economic changes that allowed a more universal access to marriage and reproduction. In the West, the male breadwinner model was enabled to develop by post-war prosperity, which, as well as bringing high wages for men, hastened the emergence of middle-class society, and introduced new household appliances that made everyday life easier (Coontz 2000). In both Western and state-socialist parts of Europe, people embarked on the marriages and parenthood that had been postponed by the Great Depression and the war (Van Bavel and Reher 2013). It was generally expected that people would marry early and have children quickly. Married couples who remained voluntarily childless were perceived as self-indulgent and indifferent to their social responsibilities (Dorbritz and Fleischhacker 1999; Dykstra and Hagestad 2007). In surveys conducted in the 1960s, almost 70 per cent of respondents in the Netherlands and over 80 per cent in the US indicated that they found the voluntary childlessness of married couples unacceptable (Dykstra and Hagestad 2007).

The socialist countries in Europe did not experience as much prosperity as Western Europe, but they did experience major economic growth (Berend 2005). While the Western democracies experienced the beginning of great social changes in the late 1960s with the spread of individualism (Inglehart 1971; Van de Kaa 1996, 2004), these were less visible in state-socialist countries. In regimes which vigorously fought individualism and actively promoted sexual puritanism and conservative gender roles, post-materialistic values could not make much progress (Sobotka 2008). The spread of the second demographic transition (SDT), though it temporarily emerged in places (Sobotka et al. 2003; Spéder and Kamarás 2008; Hoem et al. 2009), was hindered by social policies that supported the traditional family, comprising a married couple with children (McIntyre 1975; Keil and Andreescu 1999). For instance, except in East Germany, the chance of getting their own apartment was very low for single mothers or childless couples (Sobotka 2011).

The post-war boom in starting families was not pronounced in the East, but fertility was higher than in the West until the end of state socialism starting in 1989 (Sobotka 2011). Because governments believed that national power was directly linked to population size, procreation was proclaimed as the duty of every loyal citizen (Dorbritz and Fleischhacker 1999) and supported by strongly pronatalist policy measures (Frejka 1980; Stloukal 1999; Haney 2002). The most oppressive ones were introduced in Ceaus¸escu’s Romania, where abortion was made illegal in 1967, contraceptives were unavailable, and singles and childless couples over age 25 had to pay an extra tax (Baban 1999). The pressure on having children also came from people’s families, who played a much more important role in young grown-ups’ lives than in the West. In the shortage economies, the unofficial distribution channels provided by acquaintances and family members were of primary importance. These mutual dependencies encouraged the individual to conform to social expectations (Giza-Poleszczuk 2007).

We studied East–West differences in cohort childlessness over the century. We compared not only overall trends, but also the educational gradients. For cohorts born at the beginning of the century, we expected to find similar educational differences in the East and West. For women born between the 1930s and the 1960s, we expected gradients to be generally smaller in state-socialist countries, since women in these countries had fewer options for family and career trajectories. We were aware, however, that in some Central Eastern European countries childlessness was strongly stratified by education, and that educational expansion made an important contribution to fertility changes (Brzozowska 2015). For younger women who lived part of their reproductive life after the collapse of communism, the contemporary explanations of childlessness led us to expect educational differences in childlessness to be country specific rather than specific to Eastern or Western Europe.

3. Data and methods

We used census data for five-year birth cohorts of females from 1916–20 to 1961–65 aged 40–76 in the following countries: Austria (Censuses 1991, 2001), Croatia (2001, 2011), the Czech Republic (1980, 2001, 2011), France (1982, 1990, 1999, 2011), West Germany (Microcensus 2008, 2012, data for East Germany were not included owing to a low number of respondents in some educational and cohort categories), Hungary (1990, 2001), Italy (Family and Social Subjects 2003, 2009), Poland (a survey accompanying the 2002 census), Romania (1992, 2002), Slovakia (2001), Slovenia (2002), Spain (2011; we included data for women older than 76 because the consistency checks against the 1991 census showed no mortality-selection bias), and Switzerland (2000). Data for Hungary (5 per cent census sample), Romania and Slovenia (10 per cent) were derived from IPUMS International (Minnesota Population Center 2015). To allow comparability, we used a three-category classification of education: low, medium, and high, which in most cases correspond to ISCED-97 levels 0–2, 3–4, and 5–6, respectively (see UNESCO 2006 for a description of the International Standard Classification of Education). The translation of national school levels to ISCED-97 specific to our data is shown in the supplementary material. The data were collected within the EURREP project and are also part of the Cohort Fertility and Education database (CFE database) (Zeman et al. 2014).

As well as the quality checks made during the construction of the database, specific checks showed very consistent childlessness trends and patterns in the countries covered. Three issues need to be mentioned. First, in the Czech Republic low-educated women show higher levels of childlessness than the medium-educated, a pattern not seen in other countries. The absolute difference is however very small owing to the very low levels of childlessness in this country. Because the group with low education now represents less than 10 per cent of the population, strong selection effects might have prevailed. Second, in France the ISCED grouping that we adopted does not seem to match the grouping usually displayed in OECD studies: the share of the highly educated is here half the usual size (OECD 2014). However, the definition and levels displayed are comparable with those of the other countries in this study. Finally, register data from the Northern Europe countries were absent from our analysis, but we refer to the study by Andersson et al. (2009) that compares childlessness rates by level of education in Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark.

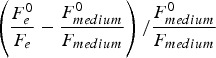

First, we analysed cohort trends in educational structure in all the countries. Then we compiled childlessness rates for women by cohort and level of education. By calculating the following relative difference in childlessness for each country and cohort we assessed the educational gradient in childlessness between women with high/low education and women with medium education:

|

(1) |

where  and

and  denote the share of childless women among women with education e (high or low) and with medium education, respectively.

denote the share of childless women among women with education e (high or low) and with medium education, respectively.

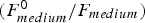

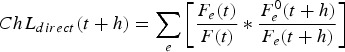

Further, we aimed to understand whether the trends in childlessness were driven by the changing educational structure of the population of females or by changes in childlessness rates within the educational sub-groups. We therefore conducted direct (at constant educational levels, equation (2a)) and indirect standardization (proportion of childless women constant in each educational group, equation (2b)). The 1936–40 cohort was chosen as the standard because it was the one for which childlessness reached a minimum in most countries:

|

(2a) |

|

(2b) |

where ChL is the proportion of childless women in the population of females, t is constant and corresponds to the 1936–40 birth cohort, while h denotes five-year cohorts, starting from 1916–20 and ending with 1956–60;  equals the proportion of women with education e in the population of females.

equals the proportion of women with education e in the population of females.

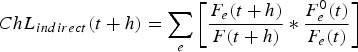

Finally, we computed the relative differences ( ) between the standardized values of childlessness and the real ones, applying the following formula:

) between the standardized values of childlessness and the real ones, applying the following formula:

| (3) |

where  denotes the standardized

denotes the standardized  as given in equations (2a) and (2b), and

as given in equations (2a) and (2b), and  equals

equals  . This measures how much the standardized levels of childlessness differ from the observed ones.

. This measures how much the standardized levels of childlessness differ from the observed ones.

4. Results

4.1. Educational differences in childlessness

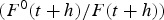

In line with the existing analyses of educational expansion, between the birth cohorts 1916 and 1965 the main shift in educational structure was in the proportions of women with low and medium education. The proportion of medium-educated women expanded to become the largest of the education groups, outnumbering the low-educated (Figure 1). The switch took place among women born in the 1940s and the early 1950s, but in Switzerland and the Czech Republic it had already taken place in the 1931–35 birth cohort, while in Italy and Romania the switch occurred with a ten-year delay. In the West, women in Italy, France, and Spain originally had lower levels of education than in the German-speaking countries but their subsequent educational transition occurred more rapidly. In the East, Hungary and Romania were particularly slow in their transition, while Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic were very fast.

Figure 1 .

Educational composition of the population in 13 European countries, women born 1916–65 Source: Cohort Fertility and Education database (www.cfe-database.org).

The proportion of women with high education, which was well below 5 per cent everywhere in the earliest cohorts, increased almost linearly but usually at a slower rate than that of medium-educated. Only in Germany, Switzerland, and Slovenia was there a parallel rise in the two curves. In the last cohort observed (1961–65), the proportion of highly educated women hardly exceeded 20 per cent. It was only in the recent period that high education spread very quickly (OECD 2014, Table A1–4a) and this is not yet visible in the cohorts presented here.

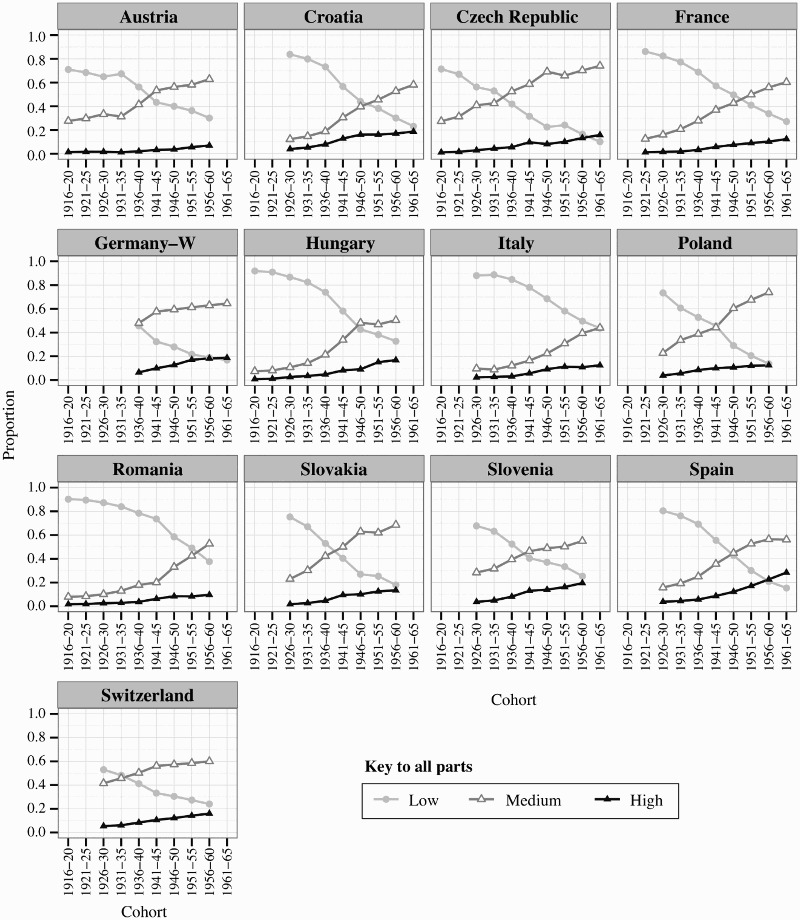

The proportion of permanently childless women varied substantially both over time and by region, but the early trends were common to most of the countries we studied (Figure 2). Indeed, for women born before the 1940s (and before the 1950s in Croatia and Romania), childlessness was decreasing. In countries where it was already low (around 5 per cent for Slovakia, 10 per cent for the Czech Republic and Croatia) it changed little over time, but in those with high childlessness rates the fall was fairly sharp (e.g., from 20 to 10 per cent in 20 years in Romania). From the 1940s birth cohorts onwards, the proportion of childless women either started to increase (Austria, West Germany, Switzerland, Spain, and Croatia, and more slowly in Slovakia and France) or it stabilized (Romania) or further decreased (Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia), at least in the cohorts observed. In the German-speaking countries it went up significantly earlier, and faster, than in the other countries.

Figure 2 .

Proportion of childless women by level of education in 13 European countries, women born 1916–65Source: As for Figure 1.

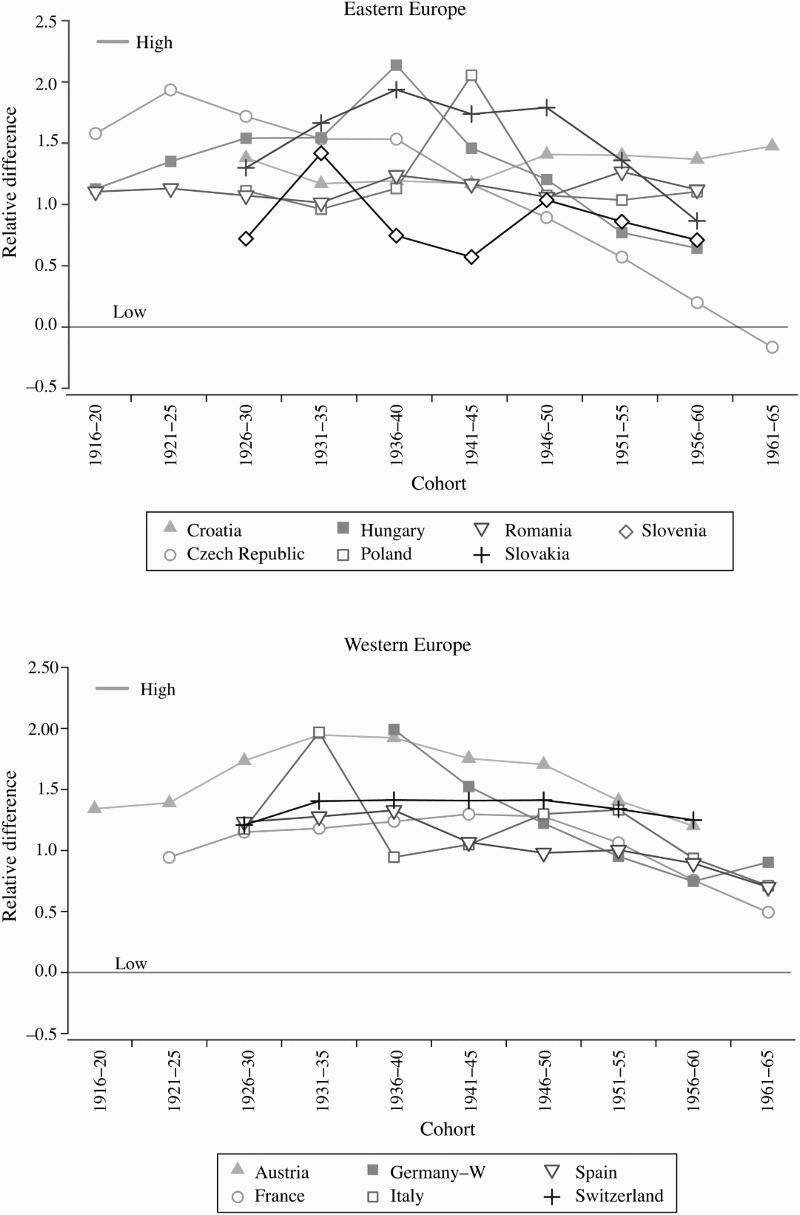

The trends in childlessness within the educational groups were at first parallel with the general trends. In the phase of increase however, the educational gradient in childlessness of highly educated vs. low-educated women diminished consistently in all countries except Romania (Figure A1 in the Appendix): levels of childlessness of highly and low-educated women became closer. This was the result of both a convergence in the levels of childlessness of low-educated and medium-educated women and a stable—even increasing in the East—gradient between medium-educated and highly educated that we document here.

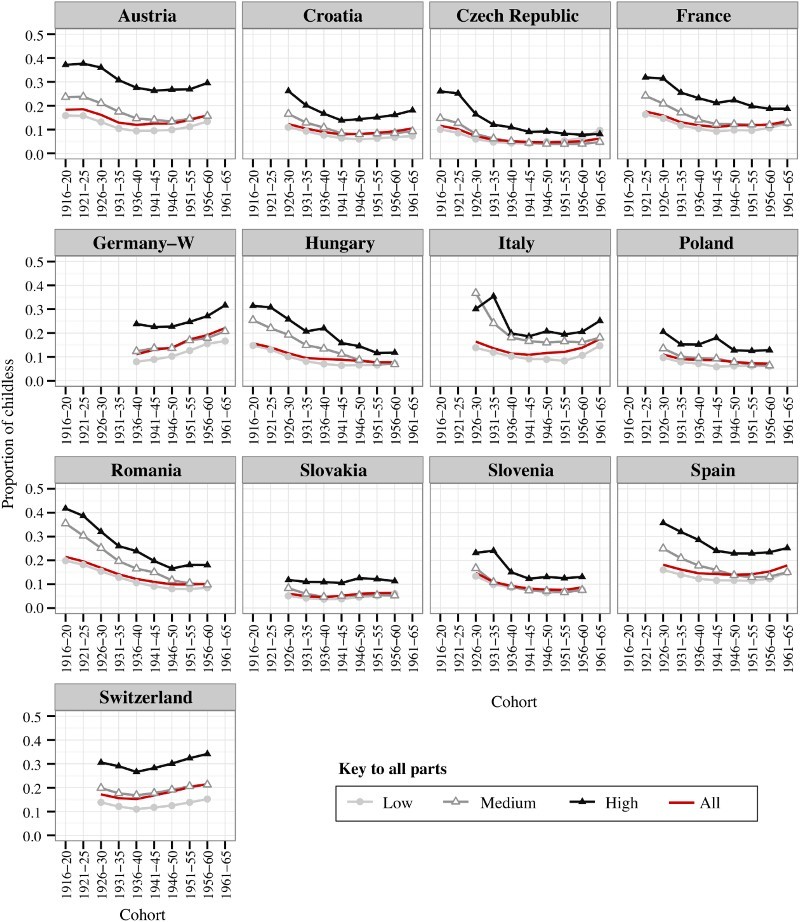

Figure 3 compares childlessness among women with low/high education with that among the medium-educated in the East and West of Europe. In all the countries studied except Croatia, childlessness rates of low-educated and medium-educated women became increasingly similar: while in the oldest cohorts childlessness among the least educated was half as high as among the medium-educated, in the more recent cohorts the difference almost vanished (though in some countries like Croatia, Italy, Switzerland, or West Germany the least educated were still 25 per cent less likely to remain childless). Possibly, in countries with a massive expansion of medium education, that is, with great upward social mobility, women with medium education were becoming more and more like those with low education in childlessness. This was not completely systematic. In several countries medium-educated women still remained childless more often than less educated women. This was the case for Austria, Switzerland, Germany, and Italy, and for Croatia and Romania. In the Czech Republic the relationship reversed and childlessness among women without a degree became twice as high as among women with intermediate education, but the levels of childlessness in all educational groups were very low (see comment in the Method section).

Figure 3 .

Relative difference in childlessness levels between low-/high- and medium-educated women, in 13 countries of Eastern and Western Europe, women born 1916–65Source: As for Figure 1.

In contrast to the convergence between low-educated and medium-educated women, childlessness among women with high education remained constantly higher than among those with medium education. This relative difference in childlessness was rather stable in the West but increased in the East, from one and a half times to twice (Figure 3). Only in France, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic did the relative childlessness level of highly vs. medium-educated women decrease in the youngest cohorts. Although the share of university graduates rose with time, childlessness remained a distinctive characteristic of highly educated women, and became even more so in most of the East—where the overall level of childlessness was much lower.

4.2. Role of educational structure and education-specific levels of childlessness in the change in the overall level of childlessness

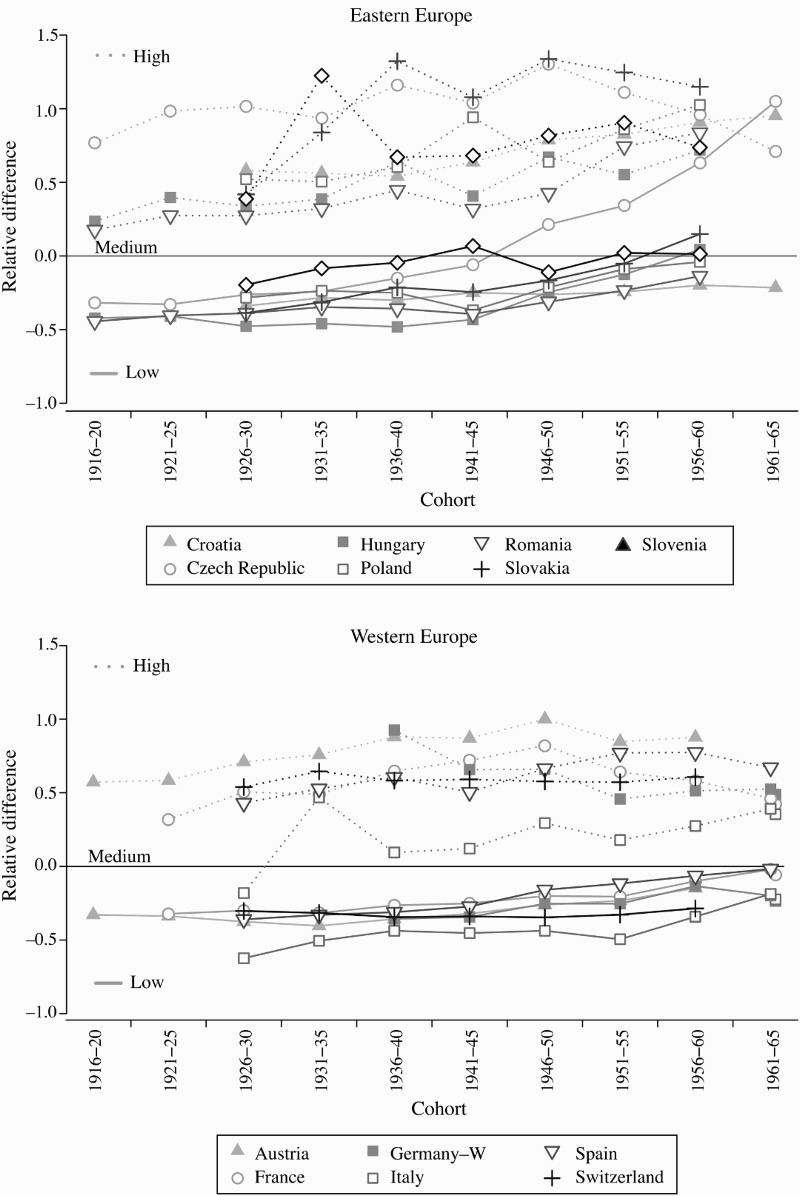

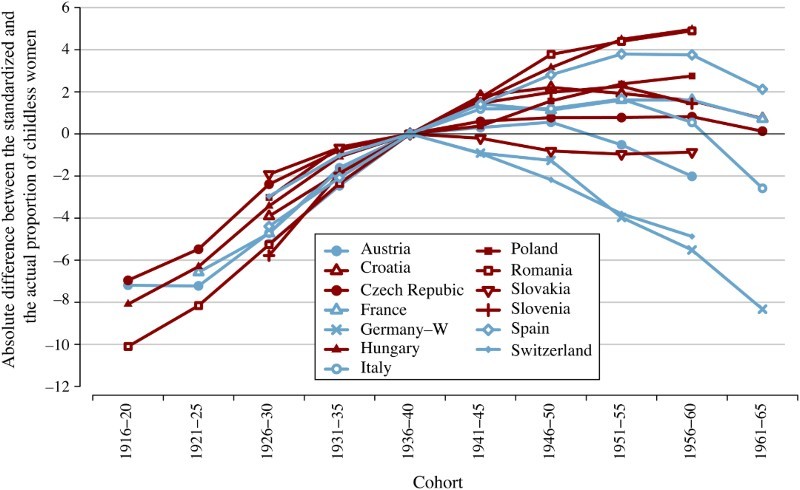

We explored the role that the extensive changes in the educational structure played in the trends in childlessness, using direct standardization. In addition, by applying indirect standardization we evaluated the contribution of the changes in the proportion of women remaining childless within distinct educational groups to the overall trends.

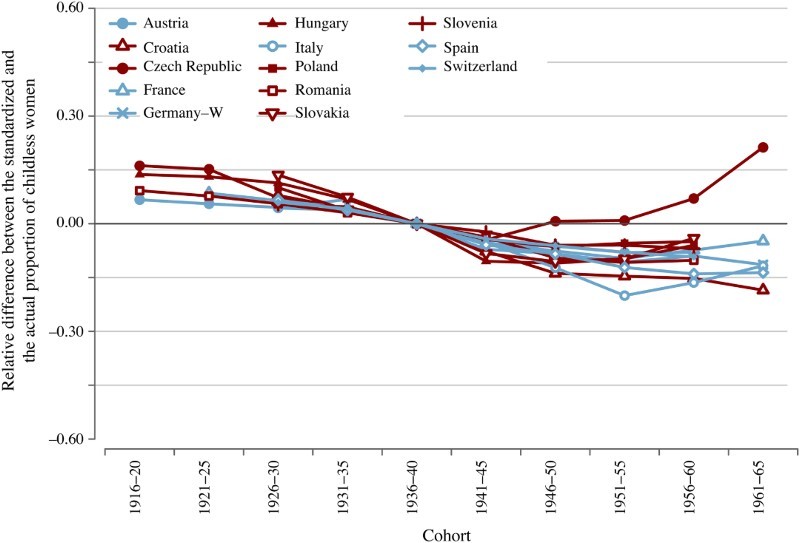

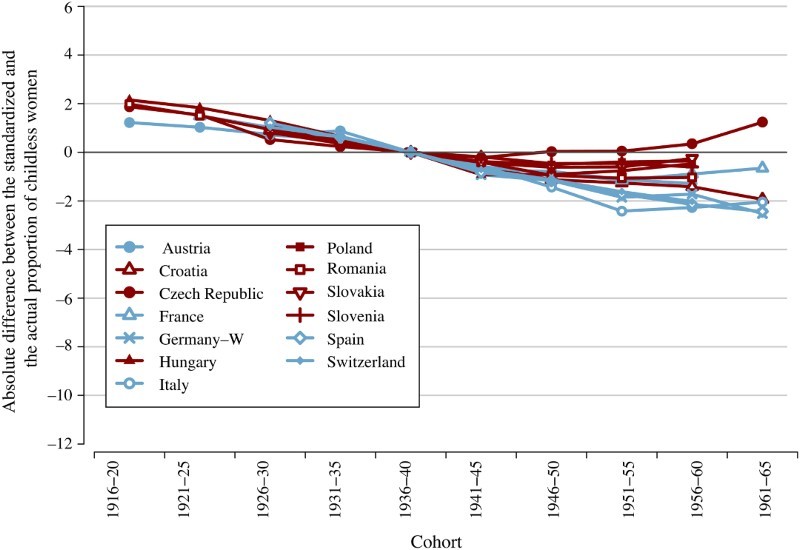

The massive rise in educational enrolment played a surprisingly minor role in the change in childlessness levels (Figure 4). If the educational structure had been the same in all cohorts as it was among women born 1936–40, the proportion of childless women would have been higher than the actual by 15 per cent in the older cohorts, and lower by 15 per cent in the younger ones (see Figure A2 in the Appendix for the absolute values of this difference in percentage points). This number corresponds to the share explained by the change in educational attainment in the US from the 1931–39 to the 1955–59 birth cohorts (Hayford 2013). Overall, the effect of increasing educational attainment was stable across cohorts and very similar across countries, though somewhat stronger in the most recent period in Western Europe.

Figure 4 .

Effect of change in educational structure on childlessness (direct standardization, structure of women by education kept constant, see equations (2a) and (3); reference cohort: 1936–40), 13 European countries, women born 1916–65Source: As for Figure 1.

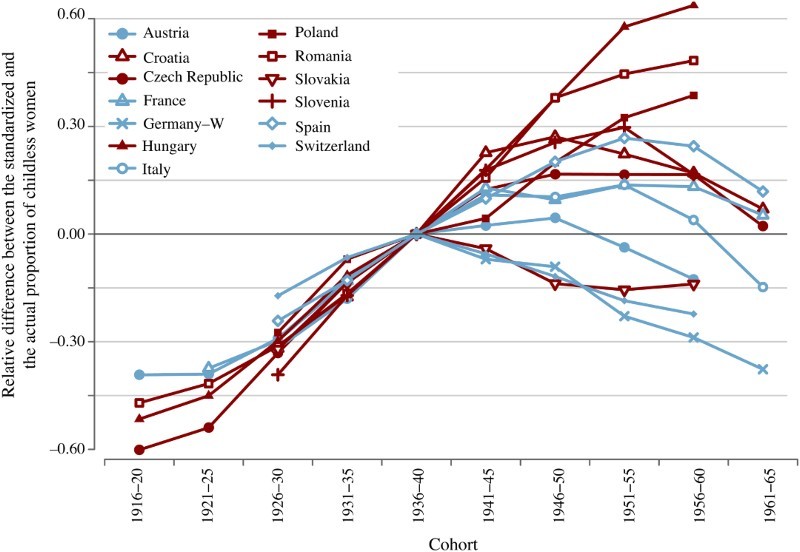

In contrast, the changes in the prevalence of childlessness within educational groups (Figure 5) had a far greater impact than the changes in educational structure. The massive decrease in childlessness among women born before 1936 was driven by decreasing childlessness within all the educational groups to a similar extent across the countries studied. The observed levels of childlessness in the 1916–20 birth cohort would have been up to 60 per cent lower than the actual ones if group-specific childlessness rates had already been as low as in the 1936–40 birth cohort. The developments for the younger cohorts varied greatly across countries, however. In the German-speaking countries childlessness started to increase steeply much earlier than in other countries, so that it would have been lower by more than 30 per cent in the 1961–65 birth cohort had it not changed within educational groups since the 1936–40 cohort. In contrast, in France, Spain, and Italy, where childlessness levels within educational groups started to increase much later, the overall level would have been higher than the actual level (this does not hold for the youngest cohort in Italy). Finally, in the East of Europe except for Slovakia, childlessness levels would have been higher by quite a large share (up to 60 per cent) if the rates had been frozen at their 1936–40 levels. The continuing decrease in childlessness in most of these countries was thus mostly due to falls in the proportion of childless women in all the educational groups.

Figure 5 .

Effect of change in childlessness rates within educational groups on the overall level of childlessness (indirect standardization, proportion of childless women within educational groups kept constant, see equations (2b) and (3); reference cohort: 1936–40), 13 European countries, women born 1916–65Source: As for Figure 1.

5. Conclusion and discussion

Over the twentieth century, cohort childlessness passed from high levels to historically low levels, and then increased again in a range of countries to the high levels observed today (Rowland 2007). Despite significant differences in the social, political, and economic set-up of the countries we studied, the decline was universal up to the 1936–40 birth cohorts. Only afterwards did the trends begin to diverge: in Western Europe childlessness usually started to rise, while in the East it levelled off or continued to decline. Childlessness originally exhibited a strongly positive educational gradient, which lessened across cohorts in most countries. Childlessness levels of lower- and medium-educated women clearly converged, and became equal in many Eastern European countries. In its higher level of childlessness, the group of highly educated women remained distinctive despite its gradual growth, and in the East of Europe it became even more different from the group of medium-educated women. The dramatic increase in the educational attainment of females in the second half of the century pushed up the proportion of childless women much less than one could have expected, and in the period under study the overall level of childlessness was largely driven by childlessness trends within educational groups.

The reason that growing educational attainment played such a minor direct role in childlessness might be that cultural and socio-economic changes affected family formation in all educational strata. Socio-economic developments during the first two decades after the Second World War made women more likely to start a family irrespective of their level of education (Van Bavel et al. 2015). The economic prosperity, very low unemployment, increasing wages of men (in the West) together with improving health and living conditions made it much easier for the lower strata to start a family—they were more likely to marry and have children and to have them much earlier than before. As the demand for qualified women in the labour force boomed, it became possible for the better educated to combine family and work and easier for women to re-enter the labour force when the children reached school age (Goldin 2006). All social strata were also eventually affected by the pronatalist measures implemented in the state-socialist countries and the socio-economic and cultural changes that initiated the SDT in the West in the late 1960s.

At the outset of our study we thought it likely that the growing demand for a more educated labour force and the expansion of educational attainment might have made the secondary and high education categories less selective as they absorbed people from lower strata. However, despite highly educated women becoming gradually more numerous and more in demand in the marriage market (Esteve 2012), we could not find any evidence of a decrease in their distinctively high rates of childlessness. It is difficult to determine whether highly educated women were more likely to remain childless because their university degree and the career opportunities it made possible led them to postpone or forgo motherhood, or because those who opted to stay longer in education were less family-oriented. One noteworthy fact is that for most of the time under study in both the East and the West, it was very difficult for women with ambitious career plans to reconcile work and childbearing. Day-care facilities for children were not widely available before the 1970s (Willekens et al. 2015, p. 2).

We identified three plausible reasons for the gradual convergence in most countries of the childlessness rates of the least educated women with those of holders of secondary school diplomas. First, in the second half of the twentieth century, the unprecedented economic and medical developments that brought adequate resources and a healthier lifestyle to the lower social strata might have played an important role in gradually bringing the fertility behaviour of less educated people closer to that of other groups. Second, at a time of very strong upward mobility, women from the lower strata may have partially assimilated the values of those in the medium educational group in which they had newly arrived (Sobel’s (1985) acculturation thesis). Finally, in some countries convergence may be a product of the greater compatibility of work and family building than in the past for women with secondary education. These were the women who benefited most from the expansion of office work, which needed educated personnel and was considered suitable for women (Cherlin 1983; Goldin 2006). The development meant that middle-class women who wanted to stay in the labour market did not have to forgo marriage and motherhood. This factor was absent in the German-speaking countries, where work and childbearing seem to have remained substantially incompatible regardless of educational level (Dorbritz and Ruckdeschel 2007; Neyer and Hoem 2009). In these countries, even medium-educated women remained more likely to be childless than those without a degree.

University graduates were much more likely to stay childless than other groups in both Western and state-socialist countries. This finding might be surprising given the explicitly egalitarian ethos of state-socialist regimes. However, it has been shown that while the economic disparities were much smaller in those countries than in the capitalist countries, the social inequalities remained quite marked (Szelenyi 1978, 1982; Andorka 1995; Doman´ski 2004). Under both socialist and capitalist regimes, university education tended to be a family characteristic, passed on from generation to generation (Ganzeboom and Nieuwbeerta 1999). This might have fostered the social and cultural distinctiveness of highly educated women, including distinctive family-formation behaviour (Kivinen et al. 2007). In many countries in the East, the level of childlessness among highly educated women seemed in fact to become increasingly distinct from that of their medium-educated counterparts. Overall levels of childlessness, however, remained much lower in the East than in the West. Even recently, highly educated women in the East often displayed levels below the overall levels in the West. If in their increased childlessness, highly educated women are forerunners of new behaviour, as they have been in other characteristics of family career (Lesthaeghe 2010; Ní Bhrolcháin and Beaujouan 2013), the increase might herald a forthcoming increase in childlessness in all social strata in the East. Interestingly, the higher propensity of graduates to remain childless seems to have dwindled somewhat for a small number of countries in the East and West in the most recent birth cohorts we studied, a finding that reminds us of the recent convergence and even crossover in childlessness levels of educational groups in some Northern Europe countries (Andersson et al. 2009).

In the later period, childlessness differences grew both between and within the East and West. The East shows as much diversity as the West of Europe in childlessness levels and educational attainment, and this diversity does not seem to correspond to strictly regional variations. For instance, in both Romania and Hungary, education was late in becoming widespread, childlessness decreased very quickly, and educational differentials in childlessness followed quite similar paths. Poland, Slovenia, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic showed an earlier increase in educational attainment, low childlessness rates, and a full convergence in the levels of childlessness of low- and medium-educated women. The trends in Croatia were in between those of these two groups of countries. While researchers tend to group Western European countries by policy and family behaviours (Basten et al. 2014), little has been done to do the same for Eastern countries (Sobotka 2011).

Our study covers the 1916–65 birth cohorts, and childlessness rates are known to have increased further in subsequent cohorts in most of the countries we studied (Frejka 2008; Masson 2013; Berrington et al. 2015; Miettinen et al. 2015). Additionally, women are now acquiring tertiary education in most European countries to a greatly increased extent (OECD 2014). While in the period under study, the intermediate level of education was fuelling the increase in educational attainment, in this new phase highly educated women, among whom childlessness has been shown to be consistently more common, are becoming more numerous. Again, one may wonder whether the current and future increase in childlessness will be driven by the increasing proportion of women with tertiary education, as seems to have been the case in the UK for the 1965–69 birth cohorts (Berrington et al. 2015). Conversely, it is possible that when the proportion of the highly educated becomes sufficiently dominant, their fertility behaviour will start to become more similar to that of other groups, as seen in the most recent cohorts in France and the US (Kravdal and Rindfuss 2008; Masson 2013).

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Figure A1 .

Relative difference in childlessness levels between high- and low-educated women, 13 countries in Eastern and Western Europe, women born 1916–65

Source: As for Figure 1.

Figure A2 .

Effect of the change in educational structure on childlessness (direct standardization, structure of women by education kept constant, see equations (2a) and (3); reference cohort: 1936–40), 13 countries in Eastern and Western Europe, women born 1916–65

Source: As for Figure 1.

Figure A3 .

Effect of the change in childlessness rates within educational groups on the overall level of childlessness (indirect standardization, proportion of childless women within educational groups kept constant, see equations (2a) and (3); reference cohort: 1936–40), 13 countries in Eastern and Western Europe, women born 1916–65

Source: As for Figure 1.

Notes

Eva Beaujouan, Zuzanna Brzozowska, and Kryštof Zeman are at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, VID/ÖAW, WU), Vienna Institute of Demography/Austrian Academy of Sciences, Welthandelsplatz 2, 1020 Vienna, Austria. E-mail: eva.beaujouan@oeaw.ac.at. Zuzanna Brzozowska is also at the Warsaw School of Economics.

This research was funded by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC Grant agreement no. 284238 (EURREP project). The CFE database, constructed within this project, is accessible at http://www.cfe-database.org. IPUMS data were originally produced by the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, the Romanian National Institute of Statistics, and the Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. The results of the study were presented at the annual conference of the British Society for Population Studies in Winchester in 2014. We thank the EURREP team, and particularly Tomáš Sobotka, who provided comments on an earlier draft of this study.

References

- Andersson G., Rønsen M., Knudsen L. B., Lappegård T., Neyer G., Skrede K., Teschner K., Vikat A. Cohort fertility patterns in the Nordic countries. Demographic Research. 2009;20(14):313–352. [Google Scholar]

- Anderton D. L., Tsuya N. O., Bean L. L., Mineau G. P. Intergenerational transmission of relative fertility and life course patterns. Demography. 1987;24(4):467–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andorka R. Changes in Hungarian society since the second world war. Macalester International. 1995;2(12):114–133. [Google Scholar]

- Baban A. Romania. In: David H. P., Skilogianis J., editors. From Abortion to Contraception: A Resource to Public Policies and Reproductive Behavior in Central and Eastern Europe from 1917 to the Present. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1999. pp. 191–221. [Google Scholar]

- Barro R. J., Lee J.-W. A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics. 2013;104:184–198. [Google Scholar]

- Basten S., Sobotka T., Zeman K. Future fertility in low fertility countries. In: Lutz W., Butz W. P., Kc S., editors. World Population and Human Capital in the Twenty-first Century. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. pp. 39–146. [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. S. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Berend I. T. What is Central and Eastern Europe? European Journal of Social Theory. 2005;8(4):401–416. [Google Scholar]

- Berrington A. Perpetual postponers? Women’s, men’s and couple’s fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behaviour. Population Trends. 2004;117:9–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrington A., Stone J., Beaujouan E. Educational differences in timing and quantum of childbearing in Britain: a study of cohorts born 1940 − 1969. Demographic Research. 2015;33(26):733–764. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S. M., Milkie M. A. Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(3):705–725. [Google Scholar]

- Blau P. M., Duncan O. D. The American Occupational Structure. New York: Wiley; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom D. E., Trussell J. What are the determinants of delayed childbearing and permanent childlessness in the United States? Demography. 1984;21(4):591–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen R., Luijkx R., Müller W., Pollak R. Long-term trends in educational inequality in Europe: class inequalities and gender differences. European Sociological Review. 2010;26(1):31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Brewster K. L., Rindfuss R. R. Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26(1):271–296. [Google Scholar]

- Brzozowska Z. Female education and fertility under state socialism: evidence from seven Central and South Eastern European countries. Population (English Edition) 2015;70(4):731–769. [Google Scholar]

- Bulcroft R., Teachman J. D. Ambiguous constructions. Development of a childless or child-free life course. In: Coleman M., Ganong L. H., editors. Handbook of Contemporary Families. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications; 2004. pp. 116–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A. J. Changing family and household: contemporary lessons from historical research. Annual Review of Sociology. 1983;9:51–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.09.080183.000411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coontz S. The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. Reprint ed. New York, NY: Basic Books, pp; 2000. ‘Leave it to Beaver’ and ‘Ozzie and Harriet’: American families in the 1950s; pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Doman´ski H. O ruchliwos´ci społecznej w Polsce [On social mobility in Poland] Warsaw: IFiS PAN; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dorbritz J., Fleischhacker J. The former German Democratic Republic. In: David H. P., Skilogianis J., editors. From Abortion to Contraception: A Resource to Public Policies and Reproductive Behavior in Central and Eastern Europe from 1917 to the Present. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1999. pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Dorbritz J., Ruckdeschel K. Kinderlosigkeit in Deutschland — Ein europäischer Sonderweg? Daten, Trends und Gründe, [Childlessness in Germany — A special path in Europe? Data, trends and reasons] In: Konietzka D., Kreyenfeld M., editors. Ein Leben ohne Kinder. Kinderlosigkeit in Deutschland. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2007. pp. 45–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra P. A., Hagestad G. O. Childlessness and parenthood in two centuries. Different roads—different maps? Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(11):1518–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve A. The gender gap reversal in education and its effect on union formation: the end of hypergamy? Population and Development Review. 2012;38(3):535–546. [Google Scholar]

- Frejka T. Fertility trends and policies: Czechoslovakia in the 1970s. Population and Development Review. 1980;6(1):65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Frejka T. Overview chapter 2. Parity distribution and completed family size in Europe: incipient decline of the two-child family model? Demographic Research (Special Collection 7) 2008;19(4):47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Frejka T., Sardon J.-P. Childbearing Trends and Prospects in Low-fertility Countries: A Cohort Analysis. European Studies of Population. Vol. 13. Dordrecht, Boston, London: European Association for Population Studies - Kluwer Academic publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzeboom H. B. G., Nieuwbeerta P. Access to education in six Eastern European countries between 1940 and 1985. Results of a cross-national survey. Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 1999;32(4):339–357. [Google Scholar]

- Giza-Poleszczuk A. Rodzina i system społeczny [The family and the social system] In: Marody M., editor. Wymiary z˙ycia społecznego [The dimensions of social life] Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe SCHOLAR; 2007. pp. 290–317. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C. The long road to the fast track: career and family. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;596(1):20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C. The quiet revolution that transformed women’s employment, education, and family. The American Economic Review. 2006;96(2):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- González M.-J., Jurado-Guerrero T. Remaining childless in affluent economies: a comparison of France, West Germany, Italy and Spain, 1994–2001. European Journal of Population - Revue Européenne de Démographie. 2007;22(4):317–352. [Google Scholar]

- Goujon A. 2009 Report on changes in the educational composition of the population and the definition of education transition scenarios: The example of Italy and the Netherlands, Extended Version of Deliverable D3 in Work Package 1 (Multistate Methods) of EU (6th Framework) Funded Project MicMac: Bridging the Micro-Macro Gap in Population Forecasting. Unpublished manuscript.

- Hakim C. A new approach to explaining fertility patterns: preference theory. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(3):349–374. [Google Scholar]

- Haney L. A. Inventing the Needy: Gender and the Politics of Welfare in Hungary. Oakland: University of California Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hayford S. R. Marriage (still) matters: the contribution of demographic change to trends in childlessness in the United States. Demography. 2013;50(5):1641–61. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoem J. M., Kostova D., Jasilioniene A., Mures¸an C. Traces of the second demographic transition in four selected countries in Central and Eastern Europe: union formation as a demographic manifestation. European Journal of Population - Revue Européenne de Démographie. 2009;25(3):239–255. doi: 10.1007/s10680-009-9177-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart R. The silent revolution in Europe: intergenerational change in post-industrial societies. The American Political Science Review. 1971;65(4):991–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Keil T., Andreescu V. Fertility policy in Ceausescu’s Romania. Journal of Family History. 1999;24(4):478–492. doi: 10.1177/036319909902400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivinen O., Hedman J., Kaipainen P. From elite university to mass higher education: educational expansion, equality of opportunity and returns to university education. Acta Sociologica. 2007;50(3):231–247. [Google Scholar]

- Kneale D., Joshi H. Postponement and childlessness: evidence from two British cohorts. Demographic Research. 2008;19(58):1935–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Kolk M. Understanding transmission of fertility across multiple generations – Socialization or socioeconomics? Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 2014;35:89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Köppen K., Mazuy M., Toulemon L. Kinderlosigkeit in Frankreich [Childlessness in France] In: Konietzka D., Kreyenfeld M., editors. Ein Leben Ohne Kinder. Kinderlosigkeit in Deutschland. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2007. pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Ø., Rindfuss R. R. Changing relationships between education and fertility – a study of women and men born 1940–64. American Sociological Review. 2008;73(11):854–873. [Google Scholar]

- Kreager P. Where are the children? In: Kreager P., Schroeder-Butterfill E., editors. Ageing without Children: European and Asian Perspectives. Oxford, UK: Berghahn Books; 2004. pp. 1–45. and New York. [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenfeld M., Konietzka D. Education and fertility in Germany. In: Kreyenfeld M., Konietzka D., editors. Demographic Change in Germany. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 165–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R. J. The unfolding story of the second demographic transition. Population and Development Review. 2010;36(2):211–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letherby G. Childless and bereft? Stereotypes and realities in relation to “voluntary” and “involuntary” childlessness and womanhood. Sociological Inquiry. 2002;72(1):7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Masson L. 2013 Avez-vous eu des enfantsSi oui, combien[Do you have children? If yes, how many?], France, Portrait Social 2013.

- McIntyre R. Pronatalist programmes in Eastern Europe. Soviet Studies. 1975;27(3):366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen A., Rotkirch A., Szalma I., Donno A., Tanturri M. L. 2015 Increasing childlessness in Europe: time trends and country differences, Families and Societies Working Paper Series33.

- Minnesota Population Center . Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 6.4 [Machine-readable database] Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S. P. Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century childlessness. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(3):779–807. doi: 10.1086/229820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M. The contraceptive pill and women’s employment as factors in fertility change in Britain 1963–1980: a challenge to the conventional view. Population Studies. 1993;47(2):221–43. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000146986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyer G., Hoem J. M. Education and permanent childlessness: Austria vs. Sweden. A research note. In: Surkyn J., Deboosere P., van Bavel J., editors. Demographic Challenges for the 21st Century: A State of the Art in Demography. Brussels: VUBPRESS Brussels University Press; 2009. pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Bhrolcháin M., Beaujouan É. Education and cohabitation in Britain: a return to traditional patterns? Population and Development Review. 2013;39(3):441–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti C., Tanturri M. L. Differences in delaying motherhood across European countries: empirical evidence from the ECHP. European Journal of Population - Revue Européenne de Démographie. 2008;24(2):157–183. [Google Scholar]

- OECD 2014 Education at a Glance 2014: OECD indicators. Available: http://www.oecd.org/edu/Education-at-a-Glance-2014.pdf.

- Pooley S. Parenthood, child-rearing and fertility in England, 1850–1914. The History of the Family. 2013;18(1):83–106. doi: 10.1080/1081602X.2013.795491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S. H. Family sizes of children and family sizes of women. Demography. 1976;13(1):105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reher D., Requena M. Was there a mid-20th century fertility boom in Latin America? Revista de Historia Económica (New Series) 2014;32(3):319–350. [Google Scholar]

- Reher D., Requena M. The mid-twentieth century fertility boom from a global perspective. The History of the Family. 2015;20(3):420–445. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss R. R., Morgan S. P., Swicegood C. G. First Births in America: Changes in the Timing of Parenthood. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland D. T. Historical trends in childlessness. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(10):1311–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Sandström G. The mid-twentieth century baby boom in Sweden – Changes in the educational gradient of fertility for women born 1915–1950. The History of the Family. 2014;19(1):120–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sardon J.-P. Recent demographic trends in the developed countries. Population (English Edition) 2002;57(1):111–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel M. E. Diagonal mobility models: a substantively motivated class of designs for the analysis of mobility effects. American Sociological Review. 1981;46(6):893–906. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel M. E. Social mobility and fertility revisited: some new models for the analysis of the mobility effects hypothesis. American Sociological Review. 1985;50(5):699–712. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T. Overview chapter 6: the diverse faces of the second demographic transition in Europe. Demographic Research (Special Collection 7) 2008;19(8):171–224. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T. Fertility in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989: collapse and gradual recovery. Historical Social Research. 2011;36(2):246–296. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T. Fertility in Austria, Germany and Switzerland: is there a common pattern? Comparative Population Studies. 2012;36(2–3):263–304. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T., Zeman K., Kantorová V. Demographic shifts in the Czech Republic after 1989: a Second demographic transition view. European Journal of Population. 2003;19(3):249–277. [Google Scholar]

- Sovic S. European family history moving beyond sdtereotypes of ‘East’ and ‘West’. Cultural and Social History. 2008;5(2):141–163. [Google Scholar]

- Spéder Z., Kamarás F. Hungary: secular fertility decline with distinct period fluctuations. Demographic Research (Special Collection 7) 2008;19(18):599–664. [Google Scholar]

- Stloukal L. Understanding the ‘abortion culture’ in Central and Eastern Europe. In: David H. P., Skilogianis J., editors. From Abortion to Contraception: A Resource to Public Policies and Reproductive Behavior in Central and Eastern Europe from 1917 to the Present. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press; 1999. pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Szelenyi I. Social inequalities in state socialist redistributive economies - Dilemmas for social policy in contemporary socialist societies of Eastern Europe. In: Etzioni A., editor. Policy Research. Leiden: E.J. Brill; 1978. pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Szelenyi I. The intelligentsia in the class structure of state-socialist societies. American Journal of Sociology. 1982;88:S287–S326. [Google Scholar]

- Szołtysek M. Spatial construction of European family and household systems: promising path or blind alley? An Eastern European perspective. Continuity and Change. 2012;27(1):11–52. [Google Scholar]

- Szołtysek M., Zuber-Goldstein B. Historical family systems and the Great European Divide: the invention of the Slavic East. Demográfia. 2009;52(5):5–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tanturri M. L., Mencarini L. Childless or childfree? Paths to voluntary childlessness in Italy. Population and Development Review. 2008;34(1):51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tanturri M. L., Mills M., Rotkirch A., Sobotka T., Takács J., Miettinen A., Faludi C., Kantsa V., Nasiri D. 2015 State-of-the-art report, Childlessness in Europe, Families and Societies Working Paper Series32.

- Toulemon L. Very few couples remain voluntarily childless. Population, an English Selection. 1996;8:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO 2006 International Standard Classification of Education - ISCED 1997. Available: http://www.uis.unesco.org/Library/Documents/isced97-en.pdf (accessed: May 2015)

- Van Agtmaal-Wobma E., van Huis M. De relatie tussen vruchtbaarheid en opleidingsniveau van de vrouw [The relationship between female fertility and level of education] Bevolkingstrends2e kwartaal. 2008:32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel J. The mid-twentieth century Baby Boom and the changing educational gradient in Belgian cohort fertility. Demographic Research. 2014;30(33):925–962. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel J., Kok J. Pioneers of the modern life style? Childless couples in early-twentieth century Netherlands. Social Science History. 2010;34(1):47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel J., Reher D. S. The Baby Boom and its causes: what we know and what we need to know. Population and Development Review. 2013;39(2):257–288. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel J., Klesment M., Beaujouan E., Brzozowska Z., Puur A., Reher D. S., Requena M., Sandström G., Sobotka T., Zeman K. 2015 doi: 10.1080/00324728.2018.1498223. Women’s education and cohort fertility during the Baby Boom, Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, San Diego, April 30–May 2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Van de Kaa D. J. Anchored narratives: the story and findings of half a century of research into the determinants of fertility. Population Studies. 1996;50(3):389–432. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000149546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Kaa D. J. Is the second demographic transition a useful research concept? Questions and answers. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. 2004;2:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Willekens H., Scheiwe K., Nawrotzki K. The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America. Historical and Comparative Perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wood J., Neels K., Kil T. The educational gradient of childlessness and cohort parity progression in 14 low fertility countries. Demographic Research. 2014;31(46):1365–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Zeman K., Brzozowska Z., Sobotka T., Beaujouan É., Matysiak A. 2014 Cohort fertility and education database. Methods Protocol. Available: http://www.eurrep.org/wp-content/uploads/EURREP_Database_Methods_Protocol_Dec2014.pdf (accessed: 18 March 2015)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.