Abstract

Although dendritic nanoparticles have been prepared by many different methods, control over their degree of branching (DB) is still impossible, preventing us from understanding the effect of the DB on the properties of the nanodendrites as cancer therapeutics. Herein, we developed a novel seed-mediated method to prepare gold nanodendrites (AuNDs) in an organic solvent using long chain amines as a structural directing agent. We discovered that the DB could be tuned facilely by simply adjusting synthetic parameters, such as the solvent type, the type and concentration of the long chain amines. We found that DB tuning resulted in dramatic tunability in the optical properties in the near infrared (NIR) range, which led to significantly different performance in the photothermal cancer therapy. Our in vitro and in vivo studies revealed that AuNDs with a higher DB were more efficient in photothermal tumor destruction under a lower wavelength NIR irradiation. In contrast, those with a lower DB performed better in tumor destruction under a higher wavelength NIR irradiation, indicating that AuNDs of even lower DB should have even better photothermal cancer therapy efficiency within the second NIR window. Thus, the tunable optical properties of AuNDs in the NIR range allow us to selectively determine a suitable laser wavelength for the best cancer therapeutic performance.

Keywords: Gold, Nanodendrites, Degree of branching, Cancer therapy

1. Introduction

Nanodendrites (NDs) are a group of nanoparticles that have the characteristic hyperbranched nanostructures. Owing to their extremely large surface area that can greatly enhance the catalytic, electrochemical and drug delivery performance [1–3], NDs have recently attracted intensive research attention. Previously, NDs of metals and bimetals, including Pt [3–10], Pd [11], Au [12–14], Au–Pd [11,15], Au–Pt [16,17], Pd–Pt [1,18,19], Pd–Co [20], Pd–Ni [20,21], and Pt–Cu [22], have been synthesized by a number of different approaches. In polymer science, the degree of branching (DB) is an important parameter that determines the chemical, physical and mechanical properties of dendritic polymers [23–27]. Similarly, for inorganic dendritic nanoparticles (NPs), many of their properties such as optical extinction and catalysis might also be dependent on the DB. Although NDs of different DB can be found in particles prepared by different methods, there has not been a single synthetic system that can fabricate NDs with tunable DB. For this reason, it remains unknown how the DB would impact the various properties of dendritic NPs. On the other hand, as a non-invasive approach for cancer therapy, photothermal treatment has attracted much attention in the past decade [28]. Due to the limited penetration depth of near infrared (NIR) light into tissues, photothermal therapy has been considered more suitable for breast cancer than other types of cancer in deep tissues [29]. Ideal photothermal probes should have extremely high molar extinction coefficient, so that they can absorb light more efficiently to generate more heat. In the current work, we discovered a novel system to synthesize gold NDs (AuNDs) by using long chain primary amines as a structural directing agent. In this system, the DB of AuNDs can be manipulated facilely by simply adjusting some synthetic parameters. The resultant AuNDs have significantly higher molar extinction coefficient than other types of gold nanoparticles, such as nanospheres [30], nanorods [31], and nanocages [32], so that they can potentially act as better probes for photothermal cancer therapy. The success in the synthetic chemistry allowed us to investigate, for the first time, the dependence of optical and photothermal properties of AuNDs on their DB.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

Gold chloride (HAuCl4, 99.9%) was purchased from Strem Chemicals. Thiolated polyethyleneglycol (HS-PEG, 2k) was bought from Laysan Bio. Ascorbic acid (98%), Sodium citrate tribasic dehydrate (99%), Sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 98%), Butylamine (99.5%), Octylamine (99%), Dodecylamine (98%), Oleylamine (70%, technical grade), Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, MW10,000), and Cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB, 99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Hexadecylamine (90%), Octadecylamine (90%), and 4-Nitrophenol (99.5%) were purchased from Fluka. Ethanol, Tetrahydrofuran (THF) and Dimethylformamide (DMF) were all of analytical grade and purchased from Fisher. All chemicals were used as received.

2.2. Synthesis and phase transfer of AuNDs

2.2.1. Synthesis of spherical AuNPs seeds

The seed nanoparticles were synthesized through the reduction of gold chloride (HAuCl4) by sodium citrate. The solution containing 700 µl of 60 mM HAuCl4 and 45 ml of deionized water was first boiled for 5 min, followed by addition of 5 ml of 38.8 mM sodium citrate. The mixture was allowed to react for about 15 min, and then cooled to room temperature. Before the as-prepared AuNPs could be used as seeds for the AuNDs synthesis, they were coated with a layer of PVP. The PVP coating was done by simply dissolving 0.2 g of the polymer into the AuNPs solution and stirring for 24 h. The PVP stabilized AuNPs were then centrifuged and re-dispersed into 10 ml of ethanol. Afterwards, they could be readily used for the AuNDs synthesis.

2.2.2. Synthesis of AuNDs

To perform a synthesis, 4 ml of 0.1 M ethanolic solution of amines (butylamine, octylamine, dodecylamine, hexadecylamine, octadecylamine, oleylamine, N-methyldodecylamine, N,N-dimethyldodecylamine, or dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide), 20 µl of 60 mM HAuCl4 in ethanol, varying amount of seeds, and 15 µl of 0.4 M ascorbic acid in methanol were added subsequently into the reaction vial. The solutions were then mixed vigorously by hand for a few seconds, and then left on a rocker shaker for about 30 min to allow the formation of AuNDs. The nanoparticles were then centrifuged, washed once with chloroform and ethanol and finally redispersed into 2 ml of THF. For the synthesis carried out in chloroform, all the precursors were used in the same quantity with the only difference in the solvent.

2.2.3. Phase transfer of the hydrophobic AuNDs into water

To 2 ml of THF dispersion of AuNDs, 2 mg of HS-PEG was added. The solution was gently sonicated and left on the bench for overnight. Afterwards, the nanoparticles were collected by centrifugation, washed once with ethanol and redispersed into water.

2.3. Photothermal study of AuNDs

2.3.1. Measuring temperature profile in the aqueous solutions of AuNDs

The AuNDs of different DB for the photothermal study were all prepared with the same amount of seeds and HAuCl4, but with different types and concentrations of the long chain amines. To measure the temperature change, aqueous solutions of AuNDs (100 µl, various concentrations, i.e. 25, 50 and 100 µg/ml) were irradiated by 808 or 980 nm laser (1.0 W/cm2) for 5 min in a 96-well plate. Temperature of the solution was collected every 30 s during the irradiation by using an infrared camera (ICI 7320P).

2.3.2. In vitro photothermal therapy

The MCF-7 cells used for this study were obtained from ATCC, and cultured in Eagle's Minimal Essential Medium (EMEM, ATCC) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco. Inc). MCF-7 cells were seeded on a 24-well culture plate for 12 h. Then the AuNDs, prepared with 20 µl seeds, were added at a final concentration of 100 µg/ml and co-cultured with the cells for another 12 h. After that, free nanoparticles were removed by gentle wash. The laser (808 and 980 nm) treatment was started at an initial power density of 2.0 W/cm2 and a spot size of 5 mm for 5 min. The cells were cultured for another 4 h after the laser treatment. Thereafter, cells were stained with the LIVE/DEAD® Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kits (Invitrogen, USA). In this assay, the live and dead cells showed red and green colors under fluorescence microscope, respectively. Cell viability was obtained by counting about 300 cells in each sample. For each type of AuNDs, 3 samples were used for the study.

2.3.3. In vivo photothermal therapy

The nude mice (Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu, 3–5 weeks, female) used for in vivo photothermal therapy were purchased from Harlan Lab. To build tumors, 2.5 × 106–3 × 106 cells with 0.1 ml of saline were injected hypodermically on the left or right flank of each mice. In vivo experiments were carried out when the tumors reached an average diameter of around 5 mm. 200 µl of PEG coated AuNDs at 5.0 mg/ml in PBS were injected through tail vein of each mouse. Twenty four hours after the injection, tumors were irradiated by 808 or 980 nm laser at 1.0 W/cm2 for 5 min. A total of 5 mice were used for each group. The tumor size was recorded every 3 days after the laser treatment.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis, size manipulation and mechanism of formation study of AuNDs

The synthesis of gold NPs (AuNPs) was carried out through a seed-mediated reduction of HAuCl4 by ascorbic acid in ethanol. Primary amines of different carbon chain lengths were introduced as structure-directing agents. AuNPs obtained from 6 different amines are shown in Fig. 1. An apparent morphology dependence of AuNPs on the carbon chain length of the amines can be noticed immediately. Short chain amines, i.e. butylamine and octylamine, can only produce NPs of a few branches (Fig. 1a and b); while hyperbranched or dendritic structures are seen unambiguously on all of the NPs that were prepared with long chain amines, namely dodecylamine, hexadecylamine, octadecylamine and oleylamine (Fig. 1c–f). The seed-mediated synthesis was also carried out in secondary, tertiary and quaternary amines with long carbon chains (i.e. N-methyldodecylamine, N,N-dimethyldodecylamine and dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide), however, no hyperbranched structure can be produced (Fig. S1). In addition, long chain acids, like lauric acid, can only result in solid nanoparticles with smooth surface (Fig. S2). Thus, according to the above observation, it is reasonable to conclude that the long chain primary amines are unique in directing the formation of AuNDs.

Fig. 1.

TEM images of AuNPs synthesized in the ethanolic solution of amines of different carbon chain lengths: (a) butylamine, (b) octylamine, (c) dodecylamine, (d) hexadecylamine, (e) octadecylamine and (f) oleylamine. Dendritic structures can be seen unambiguously in amines with longer chains (c–f). Scale bar: 50 nm, which is applied to all images.

In our synthetic system, size manipulation of the AuNDs can be achieved simply by adjusting the stoichiometry of the precursors. The TEM images in Fig. 2 and S3 show AuNDs prepared by using different amounts of seeds while keeping all other reagents constant. From these images, one can tell that the size of AuNDs does change accordingly with the amount of seeds; the fewer the seeds, the larger the AuNDs. Alternatively, instead of changing the amount of seeds, size tuning can also be achieved by reducing the supply of HAuCl4. The dendritic structures can be grown onto the gold seeds of arbitrary shapes. For example, when triangular gold nanoplates and long gold nanorods were used as seeds, the branches could still grow in a well-controlled manner (Fig. S4). Our investigation on the morphological evolution of AuNDs over reaction time showed that the overall dendritic structure was produced through stepwise growth of branches (Fig. S5). In addition, the high-resolution TEM (HRTEM) examination showed that the as-synthesized AuNDs are of polycrystalline nature (Fig. S6).

Fig. 2.

Control over the AuND size can be realized by adjusting the stoichiometry of the seeds and HAuCl4. In the figure, the concentration of HAuCl4 was kept constant. The amount of seeds used was 16 × 1011, 4 × 1011, 2 × 1011, and 0.5 × 1011 particles per ml (a–d), respectively. Scale bar: 40 nm, which is applied to all images.

We then proceeded to find out the formation mechanism of the AuNDs. We discovered that the long chain amines could form rod-like nanostructures with HAuCl4, which then prohibited the free diffusion of gold ions in the solution due to their strong chelation with the amine groups [33]. Consequently, the confinement of gold ions inside the rod-like nanostructures would only allow the anisotropic deposition of atomic gold onto the seeds, which eventually ended up as a multiple-generation branched structure through a stepwise branch formation mechanism (Fig. S7and S8; Scheme S1; and text in the Supporting Information for detailed discussion).

Although there have been a number of reports on gold dendritic nanostructures, many of them were dealing with particles of tens of microns in the overall size [34–41]. Thus, those should not be confused with the nanoscale AuNDs under investigation here, as they have totally different properties and applications. Previously, colloidal AuNDs were prepared by using polymers (polypyrrole and polyaniline) and a non-commercial surfactant as the structural directing agent. However, these methods lack simplicity and manipulability, not to mention that none of them have control over the DB. In the polymer-based method, the as-prepared AuNDs were actually embedded in the polymer matrix [12,13], which can hardly be removed due to its insolubility in most types of solvents. Thus, the surface of the NPs is not readily accessible for ligand exchange and molecular conjugation, making them not suitable for biomedical applications. The synthesis based on non-commercial chemicals makes the reproduction of AuNDs by other research groups a challenging task [14]. In contrast, the AuNDs introduced in this work were synthesized by commonly available long chain amines and the surface chemistry of the NPs can be easily modified by different molecules. In this sense, our method can serve as a significantly better approach to the synthesis of high quality AuNDs.

3.2. Manipulation over the DB of AuNDs

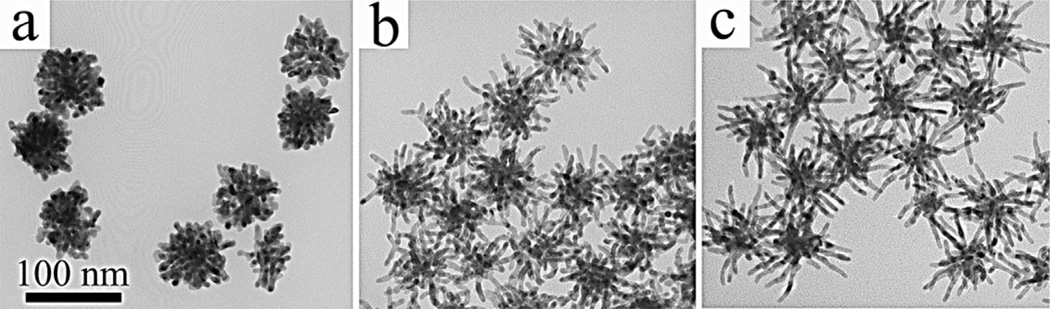

In the previous reports of synthesizing dendritic NPs of Au, Pt and Pd based metal and bimetals [3–22], no discernible difference in the DB of NPs could be observed when the synthetic parameters were adjusted, thus manipulation of DB was generally not achievable by the previous methods. However, in the current synthetic system, the DB of AuNDs can be controlled by changing the solvent type and concentrations of long chain primary amines. When the reaction was carried out in chloroform, instead of ethanol, the resultant NPs were significantly longer in branch length, while the overall number of branches on a single NP had been reduced (Fig. S9). In other words, the AuNDs prepared in chloroform are lower in the DB than those made in ethanol. More sophisticated control over the DB can be achieved by manipulating the concentration of the long chain amine. Fig. S10 shows AuNDs synthesized in 0.1, 0.4, 0.7 and 1.0 M of oleylamine. It can be seen that with increasing oleylamine concentration, the DB of AuNDs reduced correspondingly. The fine manipulability of our synthetic method provides us a number of AuNDs with tunable DB, which further allows us, for the first time, to study how the DB would affect the optical and photothermal properties of dendritic NPs. The TEM images of three selected types of AuNDs for investigation with abruptly different DB are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

TEM images of the AuNDs of high (a), medium (b) and low (c) degree of branching for the photothermal studies. The AuNDs were synthesized in (a) 0.1 M of hexadecylamine in ethanol, (b) 0.4 M of oleylamine in chloroform and (c) 1.0 M of oleylamine in chloroform, under the same amount of seeds and HAuCl4. The average diameter of branches is 7.0 ± 0.5 nm, 6.7 ± 0.2 nm, and 6.7 ± 0.4 nm in a, b and c, respectively. Scale bar: 100 nm, which is applied to all images.

3.3. Dependence of optical and in vitro photothermal properties of AuNDs on the DB

Metallic NPs with simple structures, such as nanospheres [42], nanorods [43] and nanocubes [44], usually show a sharp, narrow localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) band in their optical spectra. In contrast, the AuNDs are featured with complicated branched structures, as a result, their extinction bands are significantly broader. Here we refer the AuNDs of high, medium and low DB as H-NDs, M-NDs and L-NDs, respectively. The H-NDs have an extinction band centered at around 700 nm; however M-NDs and L-NDs have relatively low peak intensity in this range, but tend to absorb more light beyond 1000 nm (Fig. 4a). The DB-dependent optical spectra of AuNDs should be attributed to their structural difference. Namely, NPs of higher DB are mainly composed of shorter rod-like branches, which absorb intensively in the shorter wavelength region. This discovery is consistent with the earlier report that longer gold nanorods resulted in a shift of optical extinction to longer wavelength [45,46].

Fig. 4.

Dependence of optical and photothermal properties of AuNDs on DB. (a) Extinction spectra; (b) Molar extinction coefficient of AuNDs at 808, 980 and 1064 nm; (c) Temperature profiles of aqueous AuNDs solutions irradiated by 808 and 980 nm laser, both with a power density of 1.0 W/cm2, for 5 min; (d) In vitro study of cell viability after irradiation of 808 and 980 nm laser of different power densities. H, M, and L are corresponding to AuNDs of high, medium and low DB respectively. H-100, H-50 and H-25 in c mean 100, 50 and 25 µg/ml AuNDs of high DB, respectively, and so as other symbols with the prefix M and L.

For photothermal applications, metallic and semiconducting NPs that have strong extinction at the NIR region, within which the light can penetrate into relatively deep tissues, are the ideal candidates [47–51]. Most of the reported photothermal study was carried out by using NPs having absorption at 808, 980 and 1064 nm. The molar extinction coefficients (Ɛ) of AuNDs of different DB at the above-mentioned three wavelengths are summarized in Fig. 4b. One can see that H-NDs have the highest Ɛ at 808 nm, while M-NDs and L-NDs override at both 980 and 1064 nm. We then carried out further study to find out how such a difference in the optical properties would affect the performance of AuNDs in the photothermal application. Limited by the availability of lasers in our group, this study was only conducted with 808 and 980 nm lasers. We first collected the temperature profiles by directly irradiating aqueous solutions of AuNDs with lasers for 5 min and measuring the temperature change with an infrared camera. For all three different NPs concentrations (100, 50 and 25 µg/ml, respectively), the temperature profiles have shown a positive correlation to the Ɛ of AuNDs. When irradiated with 808 nm laser, H-NDs always had a larger temperature increase, however, L-NDs were hotter when irradiated with 980 nm laser (Fig. 4c).

The photothermal efficiency of different AuNDs was further compared through in vitro study. In this study, the three types of AuNDs (100 µg/ml) were co-cultured with MCF-7 breast cancer cells for 12 h. After free NPs were removed from the medium, the cells were treated by lasers for 5 min. The photothermal efficiency of NPs was then evaluated by cell viability because the lower viability indicates the better efficiency. The photothermal treatment for both types of lasers was initiated with a power density of 2.0 W/cm2. Under this power density, AuNDs of high, medium and low DB resulted in a cell viability of 37, 52 and 70% by 808 nm laser and 58, 32 and 24% by 980 nm laser, respectively (Fig. 4d). A nearly 100% cell death was observed on H-NDs at 3.5 W/cm2 (808 nm laser) and on L-NDs at 2.8 W/cm2 (980 nm laser), while cells treated by the other two types of AuNDs in each group still had fairly high viability under the corresponding laser power density. From the above study, one can see that the photothermal performance of the AuNDs is strongly dependent on their DB. Specifically, NPs of higher DB perform better with laser of shorter wavelength (e.g., 808 nm) while those of lower DB are more suited for treatment at longer wavelength (e.g., 980 and 1064 nm).

3.4. In vivo study of photothermal cancer therapy with AuNDs of different DB

We also extended the photothermal study to in vivo experiments. In this study, the AuNDs were introduced through intratumor injection. All the photothermal therapy was applied with 5 min laser irradiation at a power density of 1.0 W/cm2. Mice were housed for 3 weeks after the treatment, during which tumor volumes were recorded every 3 days. For photothermal therapy conducted by 808 nm laser, as shown in Fig. 5, tumors injected by HNDs were seen severely burnt and flattened on day 1 posttreatment, while the heat burn effect in the M-NDs and L-NDs groups was not as obvious. On day 12 posttreatment, the scarred area on the mice in the H-NDs group has remained flat and been reduced notably. However, the tumors in the M-NDs and L-NDs groups have been enlarged significantly, with the latter being the largest. In contrast, for groups using 980 nm laser as the light source, a completely reverse trend was observed. Tumors in all the three AuNDs groups were destructed heavily by the photothermal heat 1 day after the treatment. However, on day 12 posttreatment, tumors in the L-NDs groups were almost gone, while in the M-NDs and H-NDs groups, the tumors became increasingly larger in volume. In addition, we have also used an infrared camera to track the real-time temperature change in tumors during the photothermal treatment (Fig. 5d). The infrared images did reflect a positive and negative correlation between the temperature increase inside tumors and the DBs under 808 and 980 nm laser irradiation, respectively. This result is consistent with the tumor volume data shown in Fig. 5a.

Fig. 5.

In vivo photothermal treatment of MCF-7 tumors by using AuNDs of different DB. (a, b), Posttreatment tracking of tumor volume in groups treated by 808 nm and 980 nm laser, respectively; (c) Photographs of a typical mouse in each group on day 1 and day 12 posttreatment; (d) Real-time tracking of temperature increase inside tumors during the photothermal treatment by an infrared camera.

4. Conclusion

In summary, although NDs of various types of metals and bimetals have been reported in numerous works, for the first time we demonstrated that the DB of NDs in general and AuNDs in particular can be manipulated by using long chain primary amines as the structural directing agents. This work also represents a novel and simple method to prepare high quality AuNDs based on commonly available chemicals. This discovery enabled us to investigate how the DB would impact the various properties of AuNDs. We found that the manipulable DB brought tunable optical properties of AuNDs in a wide near infrared range, which further allowed us to discover, through both in vitro and in vivo experiments, the wavelength-dependent photothermal properties of AuNDs. It has been previously reported that the physical chemical properties of nanoparticles may have a significant effect on the biological fate of nanoparticles, it is thus reasonable to consider that the DB might have an impact on the interaction of AuNDs with cells (in vitro) and tumors (in vivo), which may further affect the internalization and biodistribution of AuNDs [52–54]. Such a question, though complicated, will definitely worth investigation in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the financial support from the financial support from National Institutes of Health (CA200504, CA195607, and EB021339), National Science Foundation (CMMI-1234957 and CBET-1512664), Department of Defense Office of Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs (W81XWH-15-1-0180), Oklahoma Center for Adult Stem Cell Research (434003), and Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (HR14-160). We would also like to thank the generous support from the State of Sericulture Industry Technology System (CARS-22-ZJ0402), National High Technology Research and Development Program 863 (2013AA102507), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LZ16E030001).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.06.033.

References

- 1.Lim B, Jiang MJ, Camargo PHC, Cho EC, Tao J, Lu XM, et al. Pd-pt bimetallic nanodendrites with high activity for oxygen reduction. Science. 2009;324:1302–1305. doi: 10.1126/science.1170377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanles-Sobrido M, Correa-Duarte MA, Carregal-Romero S, Rodriguez-Gonzalez B, Alvarez-Puebla RA, Herves P, et al. Highly catalytic single-crystal dendritic pt nanostructures supported on carbon nanotubes. Chem. Mater. 2009;21:1531–1535. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang L, Yamauchi Y. Block copolymer mediated synthesis of dendritic platinum nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9152–9153. doi: 10.1021/ja902485x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song YJ, Yang Y, Medforth CJ, Pereira E, Singh AK, Xu HF, et al. Controlled synthesis of 2-d and 3-d dendritic platinum nanostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:635–645. doi: 10.1021/ja037474t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song YJ, Jiang YB, Wang HR, Pena DA, Qiu Y, Miller JE, et al. Platinum nanodendrites. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:1300–1308. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ullah MH, Chung WS, Kim I, Ha CS. Ph-selective synthesis of monodisperse nanoparticles and 3d dendritic nanoclusters of ctab-stabilized platinum for electrocatalytic o-2 reduction. Small. 2006;2:870–873. doi: 10.1002/smll.200600071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin ZH, Lin MH, Chang HT. Facile synthesis of catalytically active platinum nanosponges, nanonetworks, and nanodendrites. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:4656–4662. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang L, Yamauchi Y. Facile synthesis of three-dimensional dendritic platinum nanoelectrocatalyst. Chem. Mater. 2009;21:3562–3569. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang L, Wang HJ, Nemoto Y, Yamauchi Y. Rapid and efficient synthesis of platinum nanodendrites with high surface area by chemical reduction with formic acid. Chem. Mater. 2010;22:2835–2841. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koo C-K, Wong K-L, Man CW-Y, Tam H-L, Tsao S-W, Cheah K-W, et al. Two-photon plasma membrane imaging in live cells by an amphiphilic, water-soluble cyctometalated platinum(ii) complex. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:7501–7503. doi: 10.1021/ic9007679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou YX, Wang DS, Li YD. Pd and au@pd nanodendrites: a one-pot synthesis and their superior catalytic properties. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:6141–6144. doi: 10.1039/c4cc02081b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang K, Zhang YJ, Han DX, Shen YF, Wang ZJ, Yuan JH, et al. One-step synthesis of 3d dendritic gold/polypyrrole nanocomposites via a self-assembly method. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:283–288. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pan M, Xing SX, Sun T, Zhou WW, Sindoro M, Teo HH, et al. 3d dendritic gold nanostructures: seeded growth of a multi-generation fractal architecture. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:7112–7114. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00820f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia W, Li J, Jiang L. Synthesis of highly branched gold nanodendrites with a narrow size distribution and tunable nir and sers using a multiamine surfactant. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5:6886–6892. doi: 10.1021/am401006b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang HH, Sun ZH, Yang Y, Su DS. The growth and enhanced catalytic performance of au@pd core-shell nanodendrites. Nanoscale. 2013;5:139–142. doi: 10.1039/c2nr32849f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeo KM, Choi S, Anisur RM, Kim J, Lee IS. Surfactant-free platinum-on-gold nanodendrites with enhanced catalytic performance for oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:745–748. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li YJ, Ding WC, Li MR, Xia HB, Wang DY, Tao XT. Synthesis of core-shell au-pt nanodendrites with high catalytic performance via overgrowth of platinum on in situ gold nanoparticles. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2015;3:368–376. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Yamauchi Y. Controlled aqueous solution synthesis of platinum-palladium alloy nanodendrites with various compositions using amphiphilic triblock copolymers. Chem. Asian J. 2010;5:2493–2498. doi: 10.1002/asia.201000496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu H, Mei SJ, Cao XQ, Zheng JW, Lin M, Tang JX, et al. Facile synthesis of pt/pd nanodendrites for the direct oxidation of methanol. Nanotechnology. 2014;25 doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/25/19/195702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng JN, He LL, Chen FY, Wang AJ, Xue MW, Feng JJ. A facile general strategy for synthesis of palladium-based bimetallic alloyed nanodendrites with enhanced electrocatalytic performance for methanol and ethylene glycol oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:12899–12906. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang WY, Wang DS, Liu XW, Peng Q, Li YD. Pt-ni nanodendrites with high hydrogenation activity. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:2903–2905. doi: 10.1039/c3cc40503f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor E, Chen ST, Tao J, Wu LJ, Zhu YM, Chen JY. Synthesis of pt-cu nanodendrites through controlled reduction kinetics for enhanced methanol electro-oxidation. ChemSusChem. 2013;6:1863–1867. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201300527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holter D, Burgath A, Frey H. Degree of branching in hyperbranched polymers. Acta Polym. 1997;48:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue K. Functional dendrimers, hyperbranched and star polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2000;25:453–571. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao C, Yan D. Hyperbranched polymers: from synthesis to applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2004;29:183–275. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seiler M. Hyperbranched polymers: phase behavior and new applications in the field of chemical engineering. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2006;241:155–174. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlmark A, Hawker CJ, Hult A, Malkoch M. New methodologies in the construction of dendritic materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:352–362. doi: 10.1039/b711745k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang X, El-Sayed IH, Qian W, El-Sayed MA. Cancer cell imaging and photothermal therapy in the near-infrared region by using gold nanorods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2115–2120. doi: 10.1021/ja057254a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith AM, Mancini MC, Nie SM. Bioimaging second window for in vivo imaging. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009;4:710–711. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu XO, Atwater M, Wang JH, Huo Q. Extinction coefficient of gold nanoparticles with different sizes and different capping ligands. Colloid Surf. B. 2007;58:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Near RD, Hayden SC, Hunter RE, Thackston D, El-Sayed MA. Rapid and efficient prediction of optical extinction coefficients for gold nanospheres and gold nanorods. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117:23950–23955. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho EC, Kim C, Zhou F, Cobley CM, Song KH, Chen JY, et al. Measuring the optical absorption cross sections of au-ag nanocages and au nanorods by photoacoustic imaging. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009;113:9023–9028. doi: 10.1021/jp903343p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huo ZY, Tsung CK, Huang WY, Zhang XF, Yang PD. Sub-two nanometer single crystal au nanowires. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2041–2044. doi: 10.1021/nl8013549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang JX, Ma XN, Cai HH, Song XP, Ding BJ. Nanoparticle-aggregated 3d monocrystalline gold dendritic nanostructures. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:5841–5845. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu KW, Huang CC, Hwu JR, Su WC, Shieh DB, Yeh CS. A new photothermal therapeutic agent: core-free nanostructured auxag1-x dendrites. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:2956–2964. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin Y, Song Y, Sun NJ, Zhao N, Li MX, Qi LM. Ionic liquid-assisted growth of single-crystalline dendritic gold nanostructures with a three-fold symmetry. Chem. Mater. 2008;20:3965–3972. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin TH, Lin CW, Liu HH, Sheu JT, Hung WH. Potential-controlled electrodeposition of gold dendrites in the presence of cysteine. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:2044–2046. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03273e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan M, Sun H, Lim JW, Bakaul SR, Zeng Y, Xing SX, et al. Seeded growth of two-dimensional dendritic gold nanostructures. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:1440–1442. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14721h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang JS, Han XY, Wang DW, Liu D, You TY. Facile synthesis of dendritic gold nanostructures with hyperbranched architectures and their electrocatalytic activity toward ethanol oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5:9148–9154. doi: 10.1021/am402546p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wunsche J, Cardenas L, Rosei F, Cicoira F, Gauvin R, Graeff CFO, et al. In situ formation of dendrites in eumelanin thin films between gold electrodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013;23:5591–5598. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lv Z-Y, Mei L-P, Chen W-Y, Feng J-J, Chen J-Y, Wang A-J. Shaped-controlled electrosynthesis of gold nanodendrites for highly selective and sensitive sers detection of formaldehyde. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2014;201:92–99. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bastus NG, Comenge J, Puntes V. Kinetically controlled seeded growth synthesis of citrate-stabilized gold nanoparticles of up to 200 nm: Size focusing versus ostwald ripening. Langmuir. 2011;27:11098–11105. doi: 10.1021/la201938u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ye XC, Jin LH, Caglayan H, Chen J, Xing GZ, Zheng C, et al. Improved size-tunable synthesis of monodisperse gold nanorods through the use of aromatic additives. ACS Nano. 2012;6:2804–2817. doi: 10.1021/nn300315j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skrabalak SE, Chen JY, Sun YG, Lu XM, Au L, Cobley CM, et al. Gold nanocages: synthesis, properties, and applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1587–1595. doi: 10.1021/ar800018v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye EY, Win KY, Tan HR, Lin M, Teng CP, Mlayah A, et al. Plasmonic gold nanocrosses with multidirectional excitation and strong photothermal effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8506–8509. doi: 10.1021/ja202832r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye XC, Zheng C, Chen J, Gao YZ, Murray CB. Using binary surfactant mixtures to simultaneously improve the dimensional tunability and monodispersity in the seeded growth of gold nanorods. Nano Lett. 2013;13:765–771. doi: 10.1021/nl304478h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang XH, Jain PK, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Plasmonic photothermal therapy (pptt) using gold nanoparticles. Laser Med. Sci. 2008;23:217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10103-007-0470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li YB, Lu W, Huang QA, Huang MA, Li C, Chen W. Copper sulfide nanoparticles for photothermal ablation of tumor cells. Nanomed. 2010;5:1161–1171. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hessel CM, Pattani VP, Rasch M, Panthani MG, Koo B, Tunnell JW, et al. Copper selenide nanocrystals for photothermal therapy. Nano Lett. 2011;11:2560–2566. doi: 10.1021/nl201400z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guo LR, Yan DD, Yang DF, Li YJ, Wang XD, Zalewski O, et al. Combinatorial photothermal and immuno cancer therapy using chitosan-coated hollow copper sulfide nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2014;8:5670–5681. doi: 10.1021/nn5002112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia XH, Xia YN. Gold nanocages as multifunctional materials for nanomedicine. Front. Phys Beijing. 2014;9:378–384. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Setyawati MI, Tay CY, Docter D, Stauber RH, Leong DT. Understanding and exploiting nanoparticles' intimacy with the blood vessel and blood. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:8174–8199. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00499c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee DS, Qian H, Tay CY, Leong DT. Cellular processing and destinies of artificial DNA nanostructures. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1039/c5cs00700c. http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C5CS00700C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tay CY, Setyawati MI, Xie J, Parak WJ, Leong DT. Back to basics: exploiting the innate physico-chemical characteristics of nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014;24:5936–5955. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.