Abstract

Citrus aurantifolia (family: Rutaceae) is mainly used in daily consumption, in many cultural cuisines, and in juice production. It is widely used because of its antibacterial, anticancer, antidiabetic, antifungal, anti-hypertensive, anti-inflammation, anti-lipidemia, and antioxidant properties; moreover, it can protect heart, liver, bone, and prevent urinary diseases. Its secondary metabolites are alkaloids, carotenoids, coumarins, essential oils, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and triterpenoids. The other important constituents are apigenin, hesperetin, kaempferol, limonoids, quercetin, naringenin, nobiletin, and rutin, all of these contribute to its remedial properties. The scientific searching platforms were used for publications from 1990 to present. The abstracts and titles were screened, and the full-text articles were selected. The present review is up-to-date of the phytochemical property of C. aurantifolia to provide a reference for further study.

Keywords: Cancer, Citrus aurantifolia, herb, lime, phytochemical substance, plant

INTRODUCTION

Due to the distinct aroma and delicious taste, citrus may be called a miracle fruit that is cultivated worldwide, especially in tropical and subtropical regions.[1] According to the USDA,[2] the top lemons and lime producer countries in the world in 2015 were Mexico (2270), Argentina (1450), the EU (1286), the USA (784), Turkey (668), South Africa (330), and Israel (60) in the 1000 metric tons unit. There are many natural metabolites in citrus fruit that potentially provide advantage and good for health.[3] Products of citrus fruit such as essential oil and pectin of fruit peel are used in the cosmetic[4] and pharmaceutical industries.[5,6] Citrus was studied in many countries such as Cameroon,[7] Iran,[8] Italy,[9] Nigeria,[10] Taiwan,[11] Thailand,[12] and Vietnam.[13] There are many species in the genus of Citrus, the most well-known citrus species are Citrus aurantifolia (key lime), C. hystrix (makrut lime), C. limonia (Mandarin lime), C. limon (lemon), C. jambhiri (rough lemon), C. sinensis (sweet orange), C. aurantium (sour orange), C. limetta (bitter orange), C. macroptera (wild orange), C. tachibana (tachibana orange), C. maxima (shaddock), C. medica (citron), C. nobilis (tangor), C. paradise (grapefruit), C. reticulata (tangerine), and C. tangelo (tangelo).[1,14] The present review is up-to-date of the anticancer property of C. aurantifolia to provide a reference for further study.

Plant Description

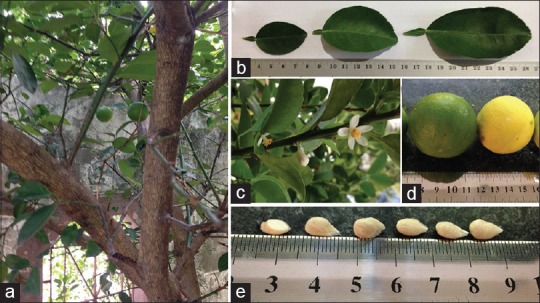

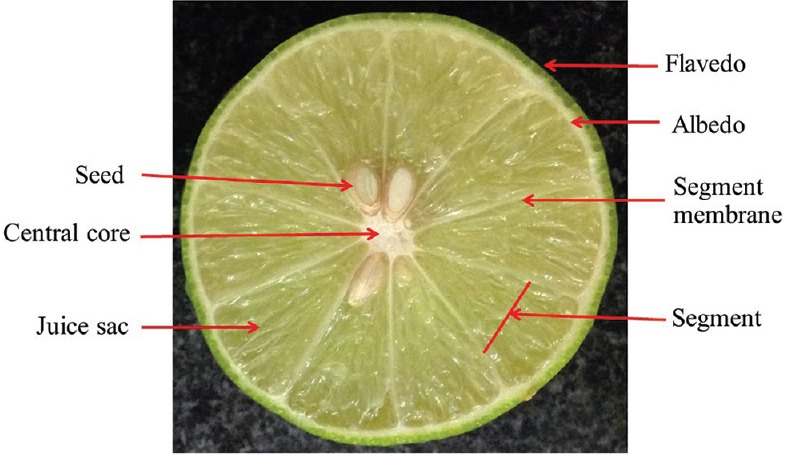

C. aurantifolia is a perennial evergreen tree that can grow to a height of 3–5 m [Figure 1]. Stem: irregularly slender branched and possesses short and stiff sharp spines or thorns 1 cm or less. Leaves: alternate, elliptical to oval, 4.5–6.5 cm long, and 2.5–4.5 cm wide with small rounded teeth around the edge. Petioles are 1–2 cm long and narrowly winged. Flowers: short and axillary racemes, bearing few flowers which are white and fragrant. Petals are 5, oblong, and 10–12 mm long. Fruits: green, round, 3–5 cm in diameter, it is yellow when rip.[15,16] All citrus fruits present the same anatomical structures [Figure 2]: (1) flavedo is the external part of the fruit and has a lot of flavonoids as its name. The outer cell wall is composed of wax and cutin for prevention of water loss from the fruit; (2) albedo is the white spongy portion, below the flavedo layer; (3) carpal membranes or septum presenting around 8–11 glandular segments, usually aligned and situated around (4) the soft central core; (5) juice sacs are yellow-green pulp vesicles; and (6) seeds are small, plump, ovoid, pale, and smooth with white embryo.[17]

Figure 1.

Gross morphology of Citrus aurantifolia (a) stems; (b) leaves; (c) white flowers in different stages; (d) ripe yellow and unripe green fruits; and (e) seeds

Figure 2.

Cross section of Citrus aurantifolia fruit

Taxonomical Classification

The taxonomy of C. aurantifolia is in the kingdom (Plantae); subkingdom (Tracheobionta); superdivision (Spermatophyta); division (Magnoliophyta); class (Magnoliopsida); subclass (Rosidae); order (Sapindales); family (Rutaceae); genus (Citrus); species (C. aurantifolia).[1,14]

Nomenclature

C. aurantifolia is native to the tropical and subtropical regions of Asia and Southeast Asia including India, China, and it was introduced to North Africa, Europe, and worldwide.[17] The vernacular name of C. aurantifolia is also known as lime (English), limah (Arabic), jeruk alit (Bali), zhi qiao (Chinese), lemmetje (Dutch), citronnier (French), limone (German), Kagzi-nimbu (Hindi), jeruk nipis (Indonesia), lima acida (Italian), jeruk pecel (Java), kroch chhmaa muul (Khmer), jeruk neepis (Malay), lamoentsji (The Netherlands), limoo (Persian), dayap (The Philippines), limao galego (Portuguese), lima agria (Spanish), taporo (Tahiti), campalam (Tamil), moli laimi (Tonga), manao (Thai), and chanh ta (Vietnam).[15]

Phytochemical Substances

C. aurantifolia contains active phytochemical substances as follows: (1) flavonoids including apigenin, hesperetin, kaempferol, nobiletin, quercetin, and rutin,[18,19,20,21,22,23] (2) flavones,[24] (3) flavanones[25] and naringenin,[26] (4) triterpenoid,[27] and (5) limonoids.[28] In addition, Lota et al.[29] reported at least 62 volatile compounds in the fruit peel oils and 59 in the leaf oils of several lime species. In the fruit peel oils, limonene was the major volatile component, followed by terpinene, pinene, and sabinene. For leaf oils, limonene, pinene, and sabinene were the major components, followed by citronellal, geranial, linalool, and neral. The bioactive compounds from citrus in many countries were reported, for example, Italy: Spadaro et al.[30] reported the fruit essential oils of C. aurantifolia as limonene (59%), β-pinene (16%), γ-terpinene (9%), and citral (5%). In the same research group, Costa et al.[9] reported the fruit essential oils of C. aurantifolia as limonene (54%), γ-terpinene (17%), β-pinene (13%), terpinolene (1%), α-terpineol (0.5%), and citral (3%). Nigeria: Okwu and Emenike[31] determined the phytochemical and vitamin contents of five varieties of citrus species; C. sinensis, C. reticulata, C. limonum, C. aurantifolia, and C. grandis. The presence of bioactive compounds in 100 g of citrus comprise alkaloids (0.4 mg), flavonoids (0.6 mg), phenols (0.4 mg), tannins (0.04 mg), ascorbic acids (62 mg), riboflavin (0.1 mg), thiamin (0.2 mg), and niacin (0.5 mg). Further, the same researchers' group including Okwu and Emenike[32] also reported that these citrus fruits contains crude protein (18%), crude fiber (8%), carbohydrate (78%), moisture (6%), crude lipid (1%), ash (8%), and food energy content was (363 g/cal) of fresh fruits. The most important minerals detected in the fruit include calcium (3%), phosphorus (0.4%), potassium (1%), magnesium (0.6%), and sodium (0.4%). Lawal et al.[10] reported that the leave essential oil of C. aurantifolia contains limonene (45%) and geranial (38%). Taiwan: Wang et al.[11] reported that the chemical substances from citrus fruit contain hesperidin, the major flavanone (6 mg/g), naringin (2 mg/g), diosmin, the major flavone (0.7 mg/g), kaempferol, the major flavanol (1 mg/g), chlorogenic acid, the major phenolic acid (0.1 mg/g), β-cryptoxanthin, the major carotenoid (7 μg/g), and β-carotene (4 μg/g), followed by total pectin (87 mg/g). Mexico: Sandoval-Montemayor et al.[33] reported that C. aurantifolia fruit peels consist of 44 volatile compounds, for example, dimethoxycoumarin (16%), cyclopentanedione (9%), methoxycyclohexane (8%), corylone (7%), palmitic acid (7%), dimethoxypsoralen (6%), α-terpineol (6%), and umbelliferone (5%).

Traditional Uses

The traditional uses or phytochemical properties of C. aurantifolia from several literature reviews are described as antibacterial,[34,35,36] antidiabetic,[37,38] antifungal,[39,40,41] antihypertensive,[42] anti-inflammation,[7] anti-lipidemia,[43,44] antioxidant,[45,46] anti-parasitic,[47,48,49,50] and antiplatelet,[24] activities. It is used for the treatment of cardiovascular,[51] hepatic,[52] osteoporosis,[53] and urolithiasis[54,55] diseases and acts as a fertility promoter.[56] Moreover, it can be used for insecticide activity.[57,58]

Cancer Incidence

Cancer is a serious public health problem worldwide that is the second leading cause of death, exceeding only by heart disease. A total of 1.6 million new cancer cases and more than five hundred thousand cancer deaths are recorded in the United States in 2015.[59] The natural products were studied, and it was tried to develop a novel anti-cancer therapy for several years.[60] The anticancer property of Citrus aurantifolia was reviewed in this article for update.

Colon Cancer

Patil et al.[61] reported that C. aurantifolia fruit from Texas, USA, consists of at least 22 volatile compounds, and its major compounds were limonene (30%) and dihydrocarvone (31%). About 100 µg/ml of C. aurantifolia extract can inhibit the growth of colon SW-480 cancer cell in 78% after 48 h of exposure. It showed the fragment of DNA and increased level of caspase-3. After a few years, Patil et al.[62] found the new three coumarins from C. aurantifolia peel from Texas that were 5-geranyloxy-7-methoxycoumarin, limettin, and isopimpinellin. About 25 µM of C. aurantifolia extract can inhibit the growth of colon SW-480 cancer cell in 67% after 72 h of exposure. The result of apoptosis was confirmed by the expression of tumor suppressor gene casapase-8/3, p53, and Bcl-2, and inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases phosphorylation.

Pancreatic Cancer

Patil et al.[63] reported that the active components of C. aurantifolia juice contain rutin, neohesperidin, hesperidin, and hesperetin. They also found limonoid substances such as limonexic acid, isolimonexic acid, and limonin. Moreover, 100 µg/ml of C. aurantifolia juice extract can stop 73–89% of pancreatic Panc-28 cancer cells growth after 96 h of exposure. The result of apoptosis was confirmed by the expression of Bax, Bcl-2, casapase-3, and p53. In the next year, Patil et al.[64] reported the five active components of C. aurantifolia seeds such as limonin, limonexic acid, isolimonexic acid, β-sitosterol glucoside, and limonin glucoside. They also reported that C. aurantifolia extract can stop the growth of pancreatic Panc-28 cancer cells with inhibitory concentration 50% (IC50) of 18–42 µM after 72 h of exposure. Moreover, the order of the induction of apoptosis was isolimonexic acid > limonexic acid > sitosterol glucoside > limonin > limonin glucoside, based on the expression ratio of Bax/Bcl-2.

Breast Cancer

Gharagozloo et al.[65] reported that the 125–500 µg/ml of C. aurantifolia fruit juice extract from Iran inhibits the growth of breast MDA-MB-453 cancer cell after 24 h of exposure. Adina et al.[66] reported that the 6 and 15 µg/ml of C. aurantifolia peel extract from Indonesia inhibits the growth of breast MCF-7 cancer cell at G1 and G2/M phase, respectively, after 48 h of exposure. The expression of p53 and Bcl-2 was also observed, which indicated the apoptosis.

Lymphoma

Castillo-Herrera et al.[67] reported that the limonin extract from C. aurantifolia seed from Mexico inhibits the growth of L5178Y lymphoma cells with IC50 of 8.5–9.0 µg/ml.

Moreover, the citrus secondary metabolites were studied for anticancer activity, for example, flavonoids on skin cancer,[68] hesperetin on colon cancer,[69] limonoids on colon cancer,[70] nobiletin on gastric cancer,[71] naringenin on prostate cancer,[72] gastric cancer,[73] and hepatocarcinoma.[26]

The information from electronic databases about the protective effect of high citrus fruit intake in the risk of stomach cancer studies until 2007 was reviewed by Bae et al.[74] Li et al.[75] reported the relationship between the citrus consumption and the reduction of cancer incidence among 42,470 Japanese adults, aged 40–79 years, in the Ohsaki National Health Insurance Cohort study from 1995 to 2003. The study revealed a positive relationship that citrus consumption could prevent the occurrence of cancer. Wang et al.[76] reviewed the protective effects of polymethoxyflavones from citrus and proposed that it inhibits carcinogenesis by several pathways in the metastasis, cell mobility, proapoptosis, and angiogenesis.

CONCLUSION

Even though citrus is a common fruit and easy to use in daily consumption, it contains many beneficial substances for human health. It may be a miracle fruit. The phytochemical substances such as alkaloids, carotenoids, coumarins, essential oils, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and triterpenoids exist in citrus abundantly. All of these substances have their board range of pharmacological properties, especially anticancer property. C. aurantifolia was studied for its effect against carcinogenesis by mechanisms such as stopping cancer cell mobility in circulatory system; so, inhibiting the metastasis, blocking the angiogenesis, and inducing tumor suppressor gene and apoptosis. The present review suggests that C. aurantifolia consumption may have a change to use for cancer therapy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

ABOUT AUTHOR

Nithithep Narang

Nithithep Narang, is currently pursuing his B.Sc. in Biological Sciences (Biomedical concentration) from Mahidol University International College. He plans to graduate by April, 2018. His senior project research paper focuses on the “Comparative evaluation of in vitro anthelmintic activity of leaves of Citrus aurantifolia and Citrus hystrix against Tubifex tubifex.” It is being carried out under the supervision and guidance of Dr. Wannee Jiraungkoorskul.

Wannee Jiraungkoorskul

Wannee Jiraungkoorskul, is currently working as Assistant Professor in the Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Thailand. She received her B.Sc. in Medical Technology, M.Sc. in Physiology, and Ph.D. in Biology. Dr. Wannee Jiraungkoorskul's current research interests are aquatic toxicopathology and efficiency of medicinal herbs.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the members of the Fish Research Unit, Department of Pathobiology, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, for their support. We also thank the anonymous reviewer and editor for their perceptive comments and positive criticism of this review article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu Y, Heying E, Tanumihardjo S. History, global distribution, and nutritional importance of Citrus fruits. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2012;11:530–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.USDA. Citrus: World markets and trade. Washington United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lv X, Zhao S, Ning Z, Zeng H, Shu Y, Tao O, et al. Citrus fruits as a treasure trove of active natural metabolites that potentially provide benefits for human health. Chem Cent J. 2015;9:68. doi: 10.1186/s13065-015-0145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiefer S, Weivel M, Smits J, Juch M, Tiedtke J, Herbst N. Citrus flavonoids with skin lightening effects – Safety and efficacy studies. Int J Appl Sci. 2010;132:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan IA. UK: CAB International; 2007. Citrus Genetics, Breeding and Biotechnology; p. 370. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ladaniya M. Goa, India: Academic Press; 2008. Citrus Fruit Biology. Technology and Evaluation; p. 593. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dongmo P, Tchoumbougnang F, Boyom F, Sonwa E, Zollo P, Menut C. Antiradical, antioxidant activities and anti-inflammatory potential of the essential oils of the varieties of Citrus limon and Citrus aurantifolia growing in Cameroon. J Asian Sci Res. 2013;3:1046–57. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zandkarimi H, Talaie A, Fatahi R. Evaluation of cultivated lime and lemon cultivars in Southern Iran for some biochemical compounds. Food. 2011;5:84–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa R, Bisignano C, Filocamo A, Grasso E, Occhiuto F, Spadaro F. Antimicrobial activity and chemical composition of Citrus aurantifolia (Christm.) Swingle essential oil from Italian organic crops. J Essent Oil Res. 2014;26:400–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawal O, Ogunwande I, Owolabi M, Giwa-Ajeniya A, Kasali A, Abudu F, et al. Comparative analysis of essential oils of Citrus aurantifolia Swingle and Citrus reticulata Blanco, from two different localities of Lagos State, Nigeria. Am J Essent Oils Nat Prod. 2014;2:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Chuang Y, Ku Y. Quantitation of bioactive compounds in Citrus fruits cultivated in Taiwan. Food Chem. 2007;102:1163–71. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaewsuksaeng S, Tatmala N, Srilaong V, Pongprasert N. Postharvest heat treatment delays chlorophyll degradation and maintains quality in Thai lime (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle cv. Paan) fruit. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2015;100:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phi N, Tu N, Nishiyama C, Sawamura M. Characterisation of the odour volatiles in Citrus aurantifolia Persa lime oil from Vietnam. Dev Food Sci. 2006;43:193–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dugo G. In: Citrus: The genus Citrus. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants – Industrial Profiles. Di Giacomo A, editor. Vol. 26. London: Taylor & Francis; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manner H, Buker R, Smith V, Ward D, Elevitch C. In: Citrus species (Citrus). Species Profiles for Pacific Island Agroforestry. 2.1. Elevitch C, editor. Holualoa, Hawaii: Permanent Agriculture Resources; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enejoh O, Ogunyemi I, Bala M, Oruene I, Suleiman M, Ambali S. Ethnomedical importance of Citrus aurantifolia (Christm) Swingle. Pharm Innov J. 2015;4:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivera-Cabrera F, Ponce-Valadez M, Sanchez F, Villegas-Monter A, Perez-Flores L. Acid limes. A review. Fresh Produce. 2010;4:116–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berhow MA, Bennett RD, Poling SM, Vannier S, Hidaka T, Omura M. Acylated flavonoids in callus cultures of Citrus aurantifolia. Phytochemistry. 1994;36:1225–7. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)89641-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawaii S, Tomono Y, Katase E, Ogawa K, Yano M. Quantitation of flavonoid constituents in Citrus fruits. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:3565–71. doi: 10.1021/jf990153+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caristi C, Bellocco E, Panzera V, Toscano G, Vadalà R, Leuzzi U. Flavonoids detection by HPLC-DAD-MS-MS in lemon juices from Sicilian cultivars. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:3528–34. doi: 10.1021/jf0262357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aranganathan S, Selvam JP, Nalini N. Effect of hesperetin, a Citrus flavonoid, on bacterial enzymes and carcinogen-induced aberrant crypt foci in colon cancer rats: A dose-dependent study. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2008;60:1385–92. doi: 10.1211/jpp/60.10.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee YC, Cheng TH, Lee JS, Chen JH, Liao YC, Fong Y, et al. Nobiletin, a Citrus flavonoid, suppresses invasion and migration involving FAK/PI3K/Akt and small GTPase signals in human gastric adenocarcinoma AGS cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;347:103–15. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loizzo MR, Tundis R, Bonesi M, Menichini F, De Luca D, Colica C, et al. Evaluation of Citrus aurantifolia peel and leaves extracts for their chemical composition, antioxidant and anti-cholinesterase activities. J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92:2960–7. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piccinelli AL, García Mesa M, Armenteros DM, Alfonso MA, Arevalo AC, Campone L, et al. HPLC-PDA-MS and NMR characterization of C-glycosyl flavones in a hydroalcoholic extract of Citrus aurantifolia leaves with antiplatelet activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:1574–81. doi: 10.1021/jf073485k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson J, Beecher G, Bhagwat S, Dwyer J, Gebhardt S, Haytowitz D, et al. Flavanones in grapefruit, lemons, and limes: A compilation and review of the data from the analytical literature. J Food Compost Anal. 2006;19:74–80. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arul D, Subramanian P. Inhibitory effect of naringenin (Citrus flavanone) on N-nitrosodiethylamine induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;434:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayaprakasha GK, Mandadi KK, Poulose SM, Jadegoud Y, Nagana Gowda GA, Patil BS. Novel triterpenoid from Citrus aurantium L. possesses chemopreventive properties against human colon cancer cells. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:5939–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poulose SM, Harris ED, Patil BS. Citrus limonoids induce apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cells and have radical scavenging activity. J Nutr. 2005;135:870–7. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lota ML, de Rocca Serra D, Tomi F, Jacquemond C, Casanova J. Volatile components of peel and leaf oils of lemon and lime species. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:796–805. doi: 10.1021/jf010924l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spadaro F, Costa R, Circosta C, Occhiuto F. Volatile composition and biological activity of key lime Citrus aurantifolia essential oil. Nat Prod Commun. 2012;7:1523–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okwu D, Emenike I. Evaluation of the phytonutrients and vitamins content of Citrus fruits. Int J Mol Med Adv Sci. 2006;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Okwu D, Emenike I. Nutritive value and mineral content of different varieties of Citrus fruits. J Food Technol. 2007;5:105–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandoval-Montemayor NE, García A, Elizondo-Treviño E, Garza-González E, Alvarez L, del Rayo Camacho-Corona M. Chemical composition of hexane extract of Citrus aurantifolia and anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis activity of some of its constituents. Molecules. 2012;17:11173–84. doi: 10.3390/molecules170911173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aibinu I, Adenipekun T, Adelowotan T, Ogunsanya T, Odugbemi T. Evaluation of the antimicrobial properties of different parts of Citrus aurantifolia (lime fruit) as used locally. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2006;4:185–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nwankwo IU, Osaro-Matthew RC, Ekpe IN. Synergistic antibacterial potentials of Citrus aurantifolia (Lime) and honey against some bacteria isolated from sputum of patients attending Federal Medical Center, Umuahia. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2015;4:534–44. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pathan R, Papi R, Parveen P, Tananki G, Soujanya P. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Citrus aurantifolia and its phytochemical screening. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2012;2:328–31. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daniels S. Citrus peel extract shows benefit for diabetes. Life Sci. 2006;79:365–73. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karimi A, Nasab N. Effect of garlic extract and Citrus aurantifolia (lime) juice and on blood glucose level and activities of aminotransferase enzymes in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. World J Pharm Sci. 2014;2:824–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dongmo PJ, Tatsadjieu L, Sonwa ET, Kuate J, Amvam Zollo P, Menut C. Essential oils of Citrus aurantifolia from Cameroon and their antifungal activity against Phaeoramularia angolensis. Afr J Agric Res. 2009;4:354–8. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tagoe D, Baidoo S, Dadzie I, Kangah V, Nyarko H. A comparison of the antimicrobial (antifungal) properties of garlic, ginger and lime on Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger and Cladosporium herbarum using organic and water base extraction methods. Int J Trop Med. 2009;7:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balamurugan S. In vitro antifungal activity of Citrus aurantifolia Linn plant extracts against phytopathogenic fungi Macrophomina phaseolina. Int Lett Nat Sci. 2014;13:70–4. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Souza A, Lamidi M, Ibrahim B, Aworet S, Boukandou M, Batchi B. Antihypertensive effect of an aqueous extract of Citrus aurantifolia (Rutaceae) (Christm.) Swingle, on the arterial blood pressure of mammal. Int Res Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;1:142–8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yaghmaie P, Parivar K, Haftsavar M. Effects of Citrus aurantifolia peel essential oil on serum cholesterol levels in Wistar rats. J Paramed Sci. 2011;2:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ezekwesili-Ofili J, Gwacham N. Comparative effects of peel extract from Nigerian grown Citrus on body weight, liver weight and serum lipids in rats fed a high-fat diet. Afr J Biochem Res. 2015;9:110–6. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reddy L, Jalli R, Jose B, Gopu S. Evaluation of antibacterial and antioxidant activities of the leaf essential oil and leaf extracts of Citrus aurantifolia. Asian J Biochem Pharm Res. 2012;2:346–54. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumari S, Sarmah N, Handique A. Antioxidant activities of the unripen and ripen Citrus aurantifolia of Assam. Int J Innov Res Sci Eng Technol. 2013;2:4811–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdelqader A, Qarallah B, Al-Ramamneh D, Das G. Anthelmintic effects of Citrus peels ethanolic extracts against Ascaridia galli. Vet Parasitol. 2012;188:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Enejoh S, Shuaibu K, Suleiman M, Ajanusi J. Evaluation of anthelmintic efficacy of extracts of Citrus aurantifolia fruit juice in mice experimentally infected with Heligmosomoides bakeri. Int J Biol Res. 2014;4:241–6. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Enejoh S, Suleiman M, Ajanusi J, Ambali S. In vitro anthelmintic efficacy of extracts of Citrus aurantifolia (Christm) Swingle fruit peels against Heligmosomoides bakeri ova and larvae. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2015;7:92–6. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Domínguez-Vigil I, Camacho-Corona M, Heredia-Rojas J, Vargas-Villarreal J, Rodríguez-De la Fuente A, Heredia-Rodríguez O, et al. Anti-giardia activity of hexane extract of Citrus aurantifolia (Christim) Swingle and some of its constituents. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2015;12:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamada T, Hayasaka S, Shibata Y, Ojima T, Saegusa T, Gotoh T, et al. Frequency of Citrus fruit intake is associated with the incidence of cardiovascular disease: The Jichi Medical School cohort study. J Epidemiol. 2011;21:169–75. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20100084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gokulakrishnan K, Senthamilselvan P, Sivakumari V. Regenerating activity of Citrus aurantifolia on paracetamol induced hepatic damage. Asian J Bio Sci. 2010;4:176–9. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shalaby N, Howaida A, Hanaa H, Nour B. Protective effect of Citrus sinensis and Citrus aurantifolia against osteoporosis and their phytochemical constituents. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5:579–88. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tosukhowong P, Yachantha C, Sasivongsbhakdi T, Ratchanon S, Chaisawasdi S, Boonla C, et al. Citraturic, alkalinizing and antioxidative effects of limeade-based regimen in nephrolithiasis patients. Urol Res. 2008;36:149–55. doi: 10.1007/s00240-008-0141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Anggraini T. Potency of Citrus (Citrus aurantium) water as inhibitor calcium lithogenesis on urinary tract. MedJ Lampung Uni. 2015;4:99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okon U, Etim B. Citrus aurantifolia impairs fertility facilitators and indices in male albino wistar rats. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2014;3:640–5. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Effiom O, Avoaja D, Ohaeri C. Mosquito repellent activity of phytochemical extracts from fruit peels of Citrus fruit species. Glob J Sci Front Res Interdiscip. 2012;12:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soonwera M. Efficacy of essential oils from Citrus plants against mosquito vectors Aedes aegypti (Linn.) and Culex quinquefasciatus (Say) J Agric Technol. 2015;11:669–81. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nirmala M, Samundeeswari A, Sankar PD. Natural plant resources in anti-cancer therapy – A review. Res Plant Biol. 2011;1:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patil J, Jayaprakasha G, Chidambara Murthy K, Tichy S, Chetti M, Patil B. Apoptosis-mediated proliferation inhibition of human colon cancer cells by volatile principles of Citrus aurantifolia. Food Chem. 2009;114:1351–8. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patil JR, Jayaprakasha GK, Kim J, Murthy KN, Chetti MB, Nam SY, et al. 5-geranyloxy-7-methoxycoumarin inhibits colon cancer (SW480) cells growth by inducing apoptosis. Planta Med. 2013;79:219–26. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1328130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Patil JR, Chidambara Murthy KN, Jayaprakasha GK, Chetti MB, Patil BS. Bioactive compounds from Mexican lime (Citrus aurantifolia) juice induce apoptosis in human pancreatic cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:10933–42. doi: 10.1021/jf901718u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patil J, Jayaprakasha G, Chidambara Murthy K, Chetti M, Patil B. Characterization of Citrus aurantifolia bioactive compounds and their inhibition of human pancreatic cancer cells through apoptosis. Microchem J. 2010;94:108–17. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gharagozloo M, Doroudchi M, Ghaderi A. Effects of Citrus aurantifolia concentrated extract on the spontaneous proliferation of MDA-MB-453 and RPMI-8866 tumor cell lines. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:475–7. doi: 10.1078/09447110260571751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adina AB, Goenadi FA, Handoko FF, Nawangsari DA, Hermawan A, Jenie RI, et al. Combination of ethanolic extract of Citrus aurantifolia peels with doxorubicin modulate cell cycle and increase apoptosis induction on MCF-7 cells. Iran J Pharm Res. 2014;13:919–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Castillo-Herrera G, Farias-Alvarez L, Garcia-Fajardo J, Delgado-Saucedo J, Puebla-Perez A, Lugo-Cervantes E. Bioactive extracts of Citrus aurantifolia swingle seeds obtained by supercritical CO2 and organic solvents comparing its cytotoxic activity against L5178Y leukemia lymphoblasts. J Supercrit Fluids. 2015;101:81–6. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pan M, Li S, Lai C, Miyaucho Y, Suzawa M, Ho C. Inhibition of Citrus flavonoids on 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate-induced skin inflammation and tumorigenesis in mice. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2012;1:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aranganathan S, Nalini N. Antiproliferative efficacy of hesperetin (Citrus flavonoid) in 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon cancer. Phytother Res. 2013;27:999–1005. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chidambara Murthy KN, Jayaprakasha GK, Patil BS. Citrus limonoids and curcumin additively inhibit human colon cancer cells. Food Funct. 2013;4:803–10. doi: 10.1039/c3fo30325j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoshimizu N, Otani Y, Saikawa Y, Kubota T, Yoshida M, Furukawa T, et al. Anti-tumour effects of nobiletin, a Citrus flavonoid, on gastric cancer include: Antiproliferative effects, induction of apoptosis and cell cycle deregulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 1):95–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gao K, Henning SM, Niu Y, Youssefian AA, Seeram NP, Xu A, et al. The Citrus flavonoid naringenin stimulates DNA repair in prostate cancer cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2006;17:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ekambaram G, Rajendran P, Magesh V, Sakthisekaran D. Naringenin reduces tumor size and weight lost in N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-induced gastric carcinogenesis in rats. Nutr Res. 2008;28:106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bae JM, Lee EJ, Guyatt G. Citrus fruit intake and stomach cancer risk: A quantitative systematic review. Gastric Cancer. 2008;11:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10120-007-0447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li WQ, Kuriyama S, Li Q, Nagai M, Hozawa A, Nishino Y, et al. Citrus consumption and cancer incidence: The Ohsaki cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:1913–22. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang L, Wang J, Fang L, Zheng Z, Zhi D, Wang S, et al. Anticancer activities of Citrus peel polymethoxyflavones related to angiogenesis and others. Biomed Res Int 2014. 2014:453972. doi: 10.1155/2014/453972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]