ABSTRACT

Esophageal cancer-related gene 4 (Ecrg4), a hormone-like peptide, is thought to be a tumor suppressor, however, little is known about the mechanism of how Ecrg4 suppresses tumorigenesis. Here, we show that the ecrg4 null glioma-initiating cell (GIC) line, which was generated from neural stem cells of ecrg4 knockout (KO) mice, effectively formed tumors in the brains of immunocompetent mice, whereas the transplanted ecrg4 wild type-GIC line GIC(+/+) was frequently eliminated. This was caused by host immune system including adaptive T cell responses, since depletion of CD4+, CD8+, or NK cells by specific antibodies in vivo recovered tumorigenicity of GIC(+/+). We demonstrate that Ecrg4 fragments, amino acid residues 71–132 and 133–148, which are produced by the proteolitic cleavage, induced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in microglia in vitro. Moreover, blockades of type-I interferon (IFN) signaling in vivo, either depleting IFN-α/β receptor 1 or using stat1 KO mice, abrogated the Ecrg4-dependent antitumor activity. Together, our findings indicate a major antitumor function of Ecrg4 in enhancing host immunity via type-I IFN signaling, and suggest its potential as a clinical candidate for cancer immunotherapy.

KEYWORDS: Ecrg4, glioma, immunosurveillance, microglia, type-I IFN

Introduction

Tumors are caused by the accumulation of genetic and epigenetic mutations in genes called tumor suppressor genes and proto-oncogenes that normally function as regulators of cell proliferation. In addition to tumors themselves, their surrounding microenvironment, which is composed by extracellular matrix and several types of cells including immune cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts, has a role to either promote or inhibit tumor growth.1 However, it still remains elusive how genetic and epigenetic mutations in tumor cells influence the surrounding cells.

Esophageal cancer-related gene 4 (Ecrg4), also known as chromosome 2 ORF 40 (C2orf40) and Augurin, was originally identified as one of the genes whose expression decreased in human squamous esophageal cell carcinomas, compared with their surrounding non-tumor cells.2 Thereafter, it has been reported that ecrg4 expression was downregulated in various types of tumors such as colorectal cancer, glioma, prostate cancer, and breast cancer because of hypermethylation of its promoter.3-6 Moreover, several papers have shown the growth inhibitory effect of Ecrg4 when overexpressed in cancer cell lines.7-9 Together, these findings suggested Ecrg4 as a tumor suppressor.

Unlike other commonly studied tumor suppressor genes, ecrg4 encodes a peptide hormone-like protein, and is thought to function on cell surface and/or in extracellular fluid.10-13 It was demonstrated that Ecrg4 was first produced as a precursor protein of 148 amino acids, and then was proteolytically processed into several different fragments.10-13 Therefore, the cleaved Ecrg4 fragment(s) seems likely to transmit growth retardation signals into the cells in an autocrine/paracrine manner, rather than Ecrg4 directly inhibits cell proliferation machinery in the cells.

Using the mouse glioma–initiating cell (GIC) models,14,15 we addressed how Ecrg4 acts as a tumor suppressor in vivo. Unexpectedly, we found that Ecrg4 from GICs, rather than tumor-surrounding cells, was essential for its tumor-suppressor function. Ecrg4 directly induced the expression of pro-inflammatory factors, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and type-I interferon (IFN), in microglia, an innate immune cell in central nervous system. Among the factors, we demonstrate that the activation of type-I IFN signaling pathway was indispensable for GIC elimination in vivo. Together, our findings identified Ecrg4 as a novel immunosurveillance activator.

Results

Ecrg4-deficient increased GIC tumorigenesis in vivo

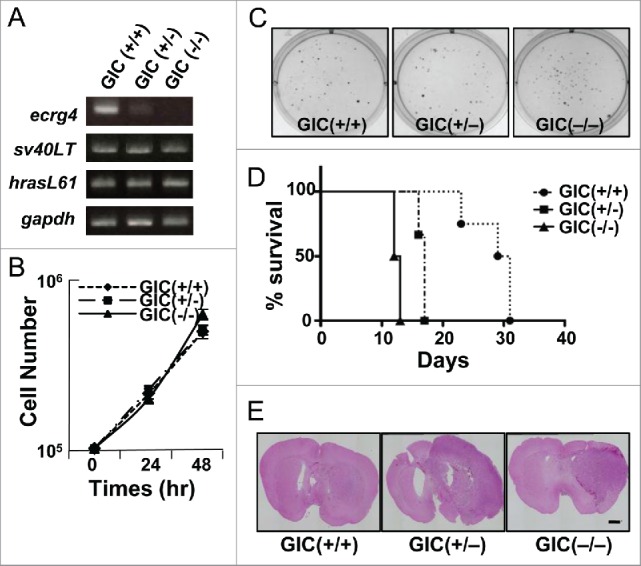

We first addressed whether Ecrg4 functions as a tumor suppressor in our mouse GIC model. We established a set of GIC lines by overexpressing sv40LT and hrasL61 in mouse embryonic neural stem cells (NSCs) from ecrg4 heterozygous intercrosses, as shown previously.15 GIC(+/+) from ecrg4+/+ NSCs clearly expressed ecrg4, whereas its expression level decreased in GIC(+/−) from ecrg4+/− NSCs and was undetectable in GIC(−/−) from ecrg4−/− ones (Fig. 1A). There was little difference in cell proliferation and colony formation in soft agar between three lines (Figs. 1B and C). In addition, overexpression of ecrg4 did not induce cell cycle arrest in any of GIC lines (data not shown). Nonetheless, we found that GIC(−/−) killed nude mice faster than other GICs, although all GIC lines formed tumors when transplanted into the brains (Figs. 1D and E). These data indicated that Ecrg4 did not inhibit GIC proliferation.

Figure 1.

Characterization of mouse GIC lines established from ecrg4 (+/+), (+/−), and (−/−) NSCs. (A) Expression of ecrg4 and exogenously introduced HRasL61 and SV40-LT in GIC lines was examined by RT-PCR. Gapdh was an internal control. (B) Cell growth curves of Ecrg4(+/+) GICs (GIC(+/+), closed circle, dotted line), Ecrg4(+/−) GICs (GIC(+/−), closed square, dashed line), and Ecrg4(−/−) GICs (GIC(−/−), closed triangle, solid line). (C) Colony formation ability of GIC lines was examined in soft agar. (D) Survival curves for nude mice injected with 104 GIC(+/+) (closed circle, dotted line, n = 4), GIC(+/−) (closed square, dashed dotted line, n = 3) and GIC(−/−) (closed triangle, solid line, n = 4). (E) Brain sections with tumors derived from GIC(+/+), GIC(+/−), and GIC(−/−) in nude mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). Scale bar, 1 mm.

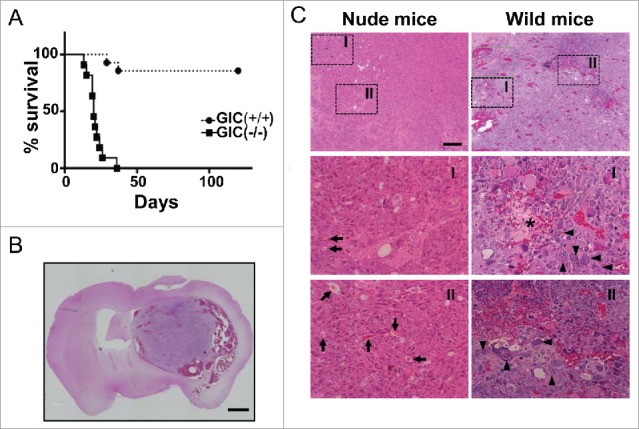

Ecrg4−/− GICs showed more malignant phenotypes in wild-type mice than in nude ones

To further examine the function of Ecrg4 in tumorigenesis, we transplanted GIC(+/+) and GIC(−/−) into brains of syngenic wild-type (WT) mice. Strikingly, we observed that GIC(−/−) killed all mice within 1 mo, whereas GIC(+/+) did only a couple of mice out of 11 by 4 mo (Fig. 2A). Together with a data that both type of GICs formed tumors in brain of nude mice (Figs. 1D and E), these suggested that Ecrg4 stimulated antitumor activity of immune system. It should be noted that tumors formed in WT mice showed more aggressive phenotypes than those in nude mice (Fig. 1E, Figs. 2B and C), and closely resembled to human glioblastoma (GBM), the most malignant type of glioma, with massive hemorrhage, pleomorphism, multinuclear giant cells, mitosis, and necrosis (Fig. 2C), suggesting the critical role of immune system for tumor malignancy.

Figure 2.

Different tumorigenicity in immunocompetent mice between GIC(+/+) and GIC(−/−). (A) Survival curves for C57BL/6 mice injected with 105 GIC(+/+) (closed circle, dotted line, n = 14) and GIC(−/−) (closed square, solid line, n = 11). p < 0.01, by log-rank test. (B) Representative images of HE staining for tumors generated with GIC(−/−) in C57BL/6 mice. Scale bar, 1 mm. (C) Comparison between brain tumor derived from GIC(−/−) in nude mice (left panels) and that in C57BL/6 mice (right panels). Middle and lower panels are the magnified images of the squared regions of upper panels. Arrows, arrowheads, and star show blood vessels, multinucleic cells and necrosis, respectively. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Since Ecrg4 secreted from the tumor-surrounding cells is thought to prevent tumorigenesis as a tumor-suppressor, we examined the tumorigenicity of both GIC(+/+) and GIC(−/−) in the ecrg4−/− brains. GIC(+/+) and GIC(−/−) formed tumors in both brains and kill mice in a similar way (Fig. S1), suggesting that Ecrg4 from tumor-surrounding cells does not act as a tumor-suppressor in our brain tumor model.

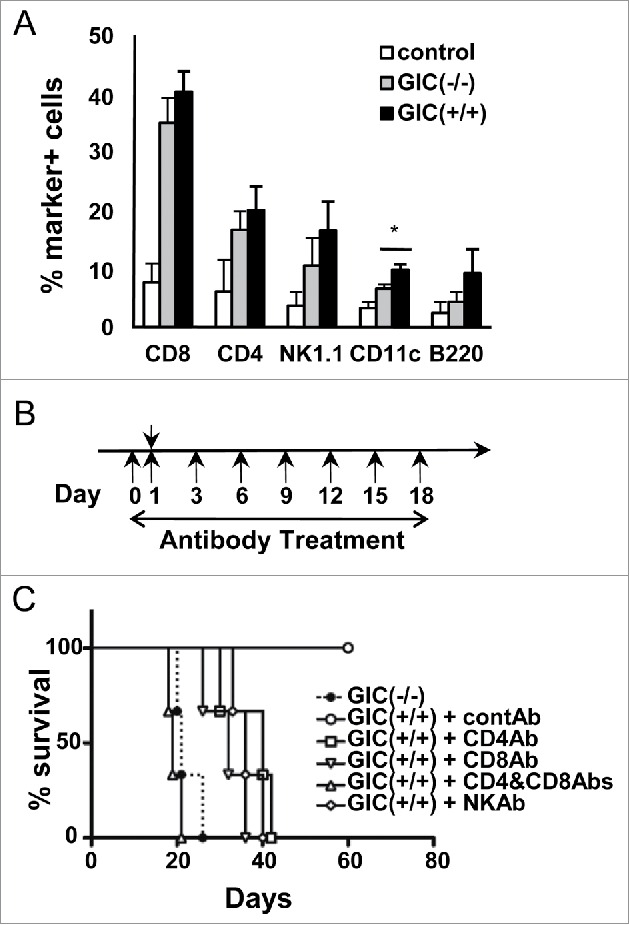

Ecrg4-stimulated immune responses

We checked which leukocytes were infiltrated into tumor-bearing brains 2 weeks after implantation of GICs, a time point that almost all mice were alive, by flow cytometry. Transplantation of GIC(+/+) and GIC(−/−) increased number of all immune cells examined, CD8+, CD4+, NK, CD11c+, and B cells, compared with the injection of medium alone (control). CD11c+ cells increased slightly by GIC(+/+) transplantation compared with GIC(−/−) one, however, there were no clear differences in cell population between GIC(+/+) and GIC(−/−) injections (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Involvement of leukocytes during GIC elimination (A) Percent immune cell marker-positive BILs that were prepared from GIC, GIC(+/+) (black columns) and GICs(−/−) (gray columns), transplanted mouse brain. Control: HBSS alone. *, p < 0.05, by t test. (B) Experimental schedule of antibody depletion experiments in GIC-transplanted mice (Day 1) were illustrated schematically. (C) Survival curve for the GIC(−/−)-transplanted mice (closed circle, dashed line) and the GIC(+/+)-transplanted ones that were treated with control (open circle, solid line) and each depletion antibodies (n = 3 of each group). Depletion of either CD4+ (open square, solid line), CD8+ (inverted open triangle, solid line), NK (open rhombus, solid line) or CD4+ & CD8+ (open triangle, solid line) cells resulted in significantly decreased survival rates (p < 0.05, by log-rank test), compared with control mice transplanted with GIC(+/+).

To identify which cytotoxic immune cells were involved in the GIC(+/+) elimination, we performed cell depletion experiments using specific monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 3B). Depletion of either CD8+, CD4+, or NK cells enabled GIC(+/+) tumorigenicity in WT mice and all of the antibody-treated mice died by about 40 d (Fig. 3C). Moreover, a combination of anti-CD8+ and CD4+ Abs accelerated GIC(+/+) tumorigenicity and shortened the survival time of the transplanted mice, as GIC(−/−) did at a similar duration. These results evaluated that Ecrg4 apparently activated antitumor immune responses.

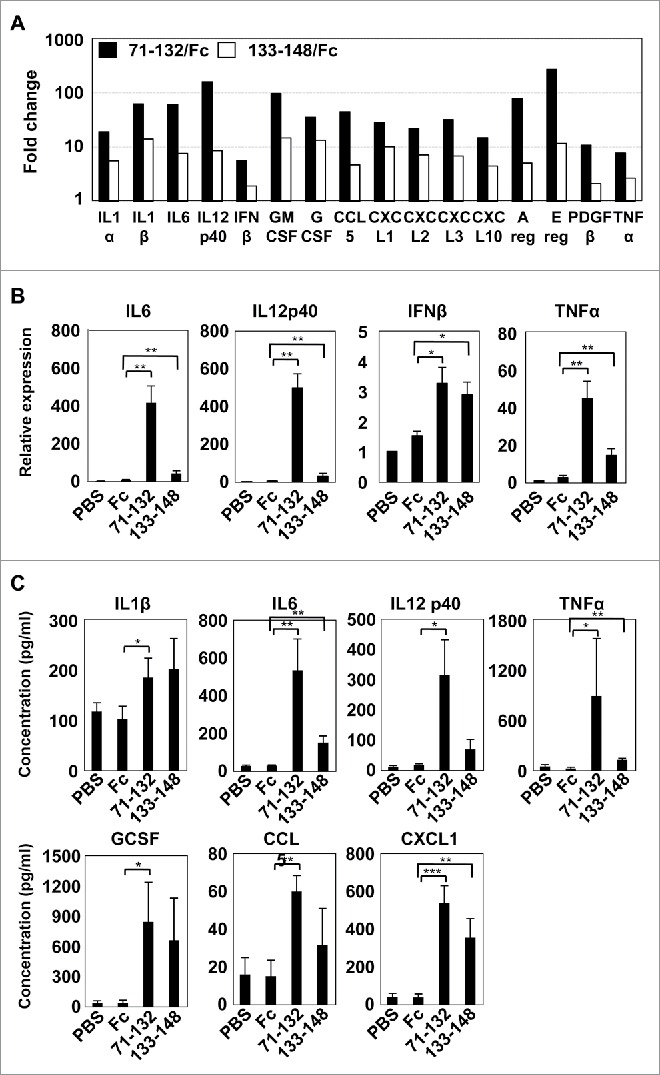

Ecrg4 induced the expression of pro-inflammatory factors in microglia

Cytokines and chemokines play a pivotal role in antitumor immunity by recruiting immune cells and activating them or by directly killing cancer cells. Previous works have shown that cleaved C-terminal Ecrg4 fragments, Ecrg4(71–148) and Ecrg4(133–148), induced secretion of plasma adrenocorticotrophin in rats and IL-6 from microglia, a primary innate immune cell in brain, respectively,16,17 indicating that the processed Ecrg4 fragments have biological functions. We therefore examined which cytokines and chemokines were induced in microglia by Ecrg4 fragments. Using microarray analyses, we found that Ecrg4(71–132) and Ecrg4(133–148) fragments increased the expression of 924 and 470 genes, respectively, while they decreased 682 and 260 genes. Both fragments commonly up and downregulated 225 and 165 genes, respectively (Fig. S2). Among the commonly upregulated genes, we noticed that the expression of many pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin 1 (il1), il6, il12 p40 subunit and tnfα, and chemokines strongly increased in the presence of Ecrg4 fragments (Fig. 4A). We confirmed the increased expression of key pro-inflammatory factors, il6, il12 p40 subunit and tnfα, and a type-I IFN ifnβ, which activates critical components of the innate and adaptive immune systems underlying cancer immunosurveillance,18,19 in the Ecrg4 fragment-treated microglia (Fig. 4B). We further evaluated the secretion of candidate cytokines and chemokines using the multiplex cytokine assay; both Ecrg4(71–132) and Ecrg4(133–148) fragments induced secretion of IL1β, IL12 p40 subunit, TNFα, IL6, granulocyte colony stimulation factor (GCSF), C–X–C motif chemokine ligand 1 (CXCL1), and C–C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5) (Fig. 4C, Fig. S3). Notably, the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in microglia by Ecrg4(71–132) was much stronger than that by Ecrg4(133–148), although both Ecrg4 fragments similarly induced the expression of many pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

Figure 4.

Increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in microglia treated with Ecrg4 fragments. (A) Microarray data of secretion factor genes upregulated by Ecrg4 fragments, 71–132 (black column) and 133–148 (white column), compared with Fc alone. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of typical pro-inflammatory cytokines, il6, il12 p40 subunit, and tnfa, and ifnb1 in primary microglia treated with 20 μg/mL of Fc, 71–132 or 133–148 for 3 h. The mRNA levels were shown as fold change over mRNA levels in microglia cells incubated with medium adding PBS instead of Fc proteins. (C) Quantitative analysis of cytokines and chemokines secreted from primary microglia that were treated with PBS, Fc, 71–132 or 133–148. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 by t test.

Ecrg4 prevented GIC tumorigenesis through the activation of type-I IFN signaling

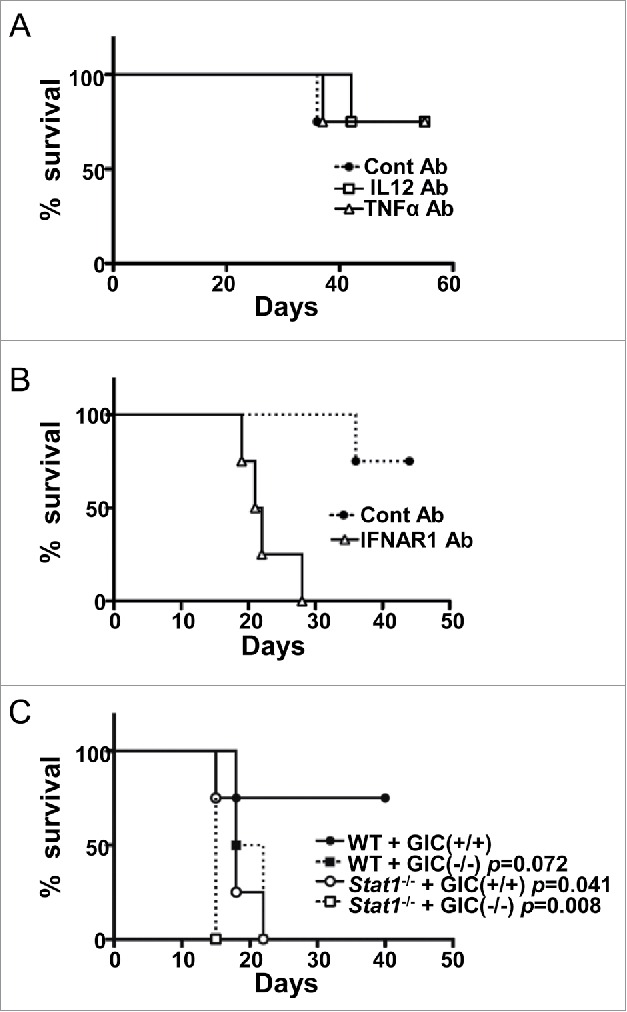

Production of IL12 p40 subunit and TNFα by microglia has been shown to contribute to both innate and adoptive antitumor immunity.20,21 We therefore examined their roles in our GIC transplantation model. Using anti-IL12 p40 subunit and TNFα depletion antibodies, we found that neither factors had apparent effects on GIC elimination (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Essential role of the type-I IFN signaling for GIC(+/+) elimination (A) Survival curve for the GIC(+/+)-transplanted WT mice that were treated with control (closed circle, dotted line), IL12-depletion (open square, solid line), or TNFα-depletion (open triangle, solid line) Abs (n = 4 of each group). (B) Survival curve for the GIC(+/+)-transplanted WT mice that were treated with control (closed circle, dotted line) or IFNAR1-depletion (open triangle, solid line) Abs (n = 4 of each group). p < 0.01, by log-rank test. (C) Survival curve for WT (closed circle and square) and stat−/− (open circle and square) mice that were transplanted with either GIC(+/+) (circles) or GIC(−/−) (squares) (n = 4 of each group). p values (versus WT+GIC(+/+)) are indicated.

Since Ecrg4 fragments enhanced the expression of ifnβ mRNA in microglia in vitro (Figs. 4A and B), we then investigated the roles of type-I IFN, one of essential cancer immunosurveillance factors, in the GIC model. Using the depletion antibody for IFN-α/β receptor 1 (IFNAR1) (22), a subunit of the type-I IFN receptor, we found that GIC(+/+) formed tumor in the brain of WT mice and killed them (Fig. 5B), as GIC(−/−) did so. To verify the antitumor function of type-I IFN in GIC(+/+) model, we further used stat1-deficient mice, in which type-I IFN signaling is completely abolished. We confirmed that GIC(+/+) formed tumors in the brain of stat1-deficient mice and killed them as GIC(−/−) did so (Fig. 5C). These results clearly indicated that type-I IFN signaling in host cells was indispensable for GIC(+/+) elimination.

Discussion

It is now widely accepted that tumorigenesis is regulated by both cancer cell proliferation and communication between cancer cells and their surrounding cells, such as immune cells. Many factors and mechanisms have been shown to be involved in cell transformation, however, it still remains to elucidate how transformed cells, which are normally excluded or destroyed in vivo, evade immunosurveillance and form tumor. Here, we showed that ecrg4-deficient GICs, GIC(−/−), formed tumors in brains of WT mice whereas ergc4-expressing GICs, GIC(+/+), were frequently eliminated, although both types of GICs similarly formed tumors in nude mouse brains, suggesting that tumor suppression was exerted more by immunosurveillance than simple growth inhibition. We demonstrated that this tumor suppression was dependent on the Ecrg4-induced activation of type-I IFN signaling pathway, which functions for immunosurveillance and tumor elimination.23-27 We also revealed that Ecrg4 induced secretion of many pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFNβ, IL6, and TNFα, and chemokines from primary microglia in culture. To generalize the potential of Ecrg4/type-I IFN pathway axis as a therapeutic target in GBM, we have checked the expression of both ecrg4 and type-I ifns in human GBM and lower grade glioma (LGG) using the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) analysis (http://cancergenome.nih.gov), and found that the expression of Ecrg4 and type-I IFNs, α5, α14, and β1, significantly decreased in GBM compared with LGG (Fig. S4). These data support our findings that the Ecrg4/type-I IFN pathway axis prevents GBM, although it is difficult to investigate their relationship directly in human. In addition, it may need to evaluate our findings using other glioma models. Altogether, we concluded Ecrg4 as an important danger-alerting factor, which activates the immune cells to eradicate tumor.

Recently, Lee and colleagues have demonstrated the antitumor function of Ecrg4(133–148) that has not only activated both NF-κB signaling pathway and phagocytosis in microglia, but has also recruited monocytes in the tumor.17 Here, we have found that Ecrg4(71–132) induced pro-inflammatory cytokines in microglia much stronger than Ecrg4(133–148), suggesting that Ecrg4(71–132) may be a primary pro-inflammatory inducer, although there is a possibility that both fragments may collaborate for the full induction of pro-inflammatory factors, or their signaling pathways may cross-talk for the activation.

It should be noted that GIC(−/−) tumors progressed in WT mice were more aggressive and showed greater similarity to human GBM than those in nude mice. This data clearly indicated that immune cells played a critical role in tumor promotion, as shown previously.28,29 We demonstrated here that Ecrg4 fragments have induced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, many of which are expressed in the classically (M1) activated macrophage/microglias,30,31 suggesting that Ecrg4 is a novel M1 polarizing factor. Therefore, in the absence of Ecrg4, microglia may keep alternative phenotype (M2) and support tumor progression. Thus, it is crucial to elucidate the molecular mechanism of how Ecrg4 modulates immune system including M1–M2 transition, using our GIC model system that is one of best models to study the communication between tumor cells and immune cells in WT mice.

In summary, we demonstrated new tumor suppressor mechanism of Ecrg4, which from cancer cells, stimulated host immune system and eradicated tumor through the activation of type-I IFN signal. We have identified Ecrg4(71–132) as a strong inducer of pro-inflammatory cytokines from microglia. In thinking about immunotherapy, the restoration of ecrg4 expression in tumor cells would be attractive, because the expression of Ecrg4 was repressed by DNA methylation without mutation or deletion of ecrg4 in many tumors. On the other side, Ecrg4(71–132) fragment can be used as an antitumor peptide, although it should be examined whether Ecrg4-induced pro-inflammatory activation causes side-effects. Modulation of Ecrg4 signaling might be also applied to cancer therapy. Further studies about identification of Ecrg4 receptor(s) and dissection the downstream event of Ecrg4 signaling might help find new targets for cancer immunotherapy.

Materials and methods

Animals

Ecrg4 KO mice were established by conventional gene targeting procedures at RIKEN CDB. The detailed characterization of Ecrg4 KO mice will be reported elsewhere. Heterozygotes were then backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice for at least eight generations. C57BL/6-background Stat1−/− mice were described previously.32 Balb/c nude and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Japan and CLEA Japan. All mouse experiments were performed following the protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Ehime University and Hokkaido University.

Plasmids and chemicals

pCMS-EGFP-H-RasL61 and pBabe-Puro-SV40LT were previously described.15 The DNA fragments of mouse Ecrg4 and its deletion mutants (corresponding to amino acids 71–132 and 133–148) were amplified by PCR and subcloned into pFuse-hIgG1-Fc2 (InvivoGen). The primers used for amplification were as follows: For mEcrg4(71–132), sense primer 5′- TGGATCCCAGCTGTGGGACCGTACGCG-3′ and antisense primer 5′- TGGATCCGTGGGGACCAATGGCCGC-3′; For mEcrg4(133–148) sense primer: 5′- TGAATTCGAGCCGGGAAAGCTTCAGG-3′ and antisense primer: 5′- TGGATCCATAGTCATCATAGTTGACACTGG-3′. Chemicals and growth factors were purchased from Sigma and PeproTech, respectively, except where otherwise indicated.

Establishment of mouse GIC lines and cell culture

Mouse model of GIC lines were generated as previously described.14,15 Briefly, NSCs were prepared from embryonic day 14.5 mouse telencephalon and expanded in DMEM/F12 (Wako, Japan) supplemented with chemicals, bFGF (10 ng/mL), and EGF (10 ng/mL) as described previously.14 Then, cells were first transfected with pBabe-Puro-SV40LT vector, followed with pCMS-EGFP-HRasL61 vector and pcDNA3.1-hyg (Invitrogen) using the Nucleofector (AMAXA, Lonza). The GFP-positive stable cells were purified by FACSAria (BD). HEK 293T cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% FCS. Hybridoma cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS. Primary microglia cells were isolated as previously described.33

Soft agar assay

The procedure has been described previously.14,15 Briefly, the cells were suspended in 0.3% top agar and layered onto 0.6% bottom agar. After the top agar solidified, culture medium was added and the cells were cultured for 20 d with medium changes every 3 d.

Intracranial cell transplantation and histopathology

Indicated number of cells was suspended in 3 µL of HBSS and injected into brains of 6–8 week-old female mice that had been anesthetized with 10% pentobarbital as described previously.14,15 When transplanted into WT mice, 10 times more GICs were used than those in nude mice. For histopathology, the dissected mouse brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight, dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Sections (10 μm thick) were rehydrated, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) using standard techniques.

Brain-infiltrating leukocyte (BIL) isolation

The procedure has been described previously.34 Briefly, brain tissues were mechanically minced, resuspended in 70% Percoll (GE), overlaid with 37% and 30% Percoll, and centrifuged for 20 min at 500 × g.

Depletion antibodies

IFNAR1 (clone MAR1-5A3), TNFα (clone MP6-XT22), and IL-12 (clone C17.8) depletion antibodies were purchased from Bio X Cell and Biolegend. Other depletion antibodies, anti-CD4+ (clone GK1.5), anti-CD8+ (clone 53.6.7), and anti-NK1.1 (clone PK136) were produced and purified from each of hybridoma cell lines. Antibodies were administered intraperitoneally (i.p) in doses of 500 µg for IL-12 and TNFα depletion and 100 µg for CD4+ cells, CD8+ cells, NK cells, and IFNAR1 depletion.

Flow cytometry

For cell-surface molecules, cell samples were stained with fluorescent dye-conjugated mAb against selected markers on ice. Then, cells were harvested and stained with 7-AAD, anti-CD4+, -CD8+, -NK1.1, CD11c, and B220 (BD Bioscience). Data were acquired by FACSCant II and analyzed with FlowJo software.

Generation of Fc fusion protein

HEK293T cells were transfected with the expression construct using polyethylenimine (PEI). Two days after transfection, conditioned medium was collected, centrifuged, passed through a 0.45-µm filter membrane. Fc fusion protein was purified by protein A-Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (Amersham Biosciences). After dialysis against PBS, purity was checked by SDS-PAGE and CBB staining.

RT-PCR

First-stranded cDNA was synthesized using Transcriptor Reverse Transcriptase (Roche). PCR reactions were carried out in a total volume of 10 µL containing 1 µL of first strand cDNA using ExTaq (Takara). RT-PCR was carried out as described.15 Primers used for amplification of specific genes were as follows: For gapdh, sense primer: 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′, antisense primer: 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′. For mouse ecrg4, sense primer: 5′-ATGAGCACCTCGTCTGCGCG-3′, antisense primer: 5′-TTAATAGTCATCATAGTTGACACT-3′. For exogenous hras, sense primer: 5′-ATGACAGAATACAAGCTTGTGGTG-3′, antisense primer: 5′-ATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAAG-3′. For SV40 LT, sense primer: 5′-ATGGATAAAGTTTTAAACAGAGAG-3′, antisense primer: 5′-TTATGTTTCAGGTTCAGGGGG-3′.

Real-time PCR was performed by using the LightCycler system (Roche) and LightCycler TaqMan Master (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples were normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin according to the ΔCt method: ΔCt = ΔCtsample – ΔCtreference. Percentages against the control sample were calculated for each sample. Primers used for amplification of specific genes were as follows: For β-actin, sense primer: 5′-AGCCATGTACGTAGCCATCCA-3′, antisense primer: 5′-TCTCCGGAGTCCATCACAATG-3′, probe: 5′-TGTCCCTGTATGCCTCTGGTCGTACCA-3′. For IFN-β, sense primer: 5′-ATGAGTGGTGGTTGCAGGC-3′, antisense primer: 5′-TGACCTTTCAAATGCAGTAGATTCA-3′, probe: 5′-AAGCATCAGAGGCGGACTCTGGGA-3′. IL12p40, sense primer: 5′-TGAACTGGCGTTGGAAGC-3′, antisense primer: 5′-GCGGGTCTGGTTTGATGA-3′, probe: Roche Universal probe #74. TNFα, sense primer: 5′-GTTCTCTTCAAGGGACAAGGCTG-3′, antisense primer: 5′- TCCTGGTATGAGATAGCAAATCGG −3′, probe: 5′-TACGTGCTCCTCACCCACACCGTCA-3′. IL6, sense primer: 5′-GAGGATACCACTCCCAACAGACC-3′, antisense primer: 5′-AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCATACA-3′, probe: 5′-CAGAATTGCCATTGCACAACTCTTTTCTCA-3′.

Cytokine and chemokine determinations

For analysis of microglia produced cytokine and chemokine profile, the supernatants were obtained from primary microglia culture 24 h after stimulation by 20 μg/mL of Ecrg4 fragments. Cytokine and chemokine concentrations were measured with Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine 23-plex Assay, according to the supplier's protocols (Bio-Rad).

Microarray hybridization and data processing

Total RNA was extracted from mouse microglia treated with 20 μg/mL of Ecrg4 fragments for 3 h using the TRIzol Plus RNA Purification System (Invitrogen). Purified RNA was then amplified and labeled with Cyanine 3 using the one-color Agilent Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit (Agilent Technologies) following the manufacturer's instructions. Labeled cRNAs were fragmented and hybridized to the Agilent mouse GE 8 × 60 K Microarray. After washing, microarrays were scanned with an Agilent DNA microarray scanner. Intensity values for each scanned feature were quantified using Agilent feature extraction software, which performed background subtractions.

Normalization was achieved using Agilent GeneSpring GX version13.1. After normalization, hierarchical sample clustering of the expressed genes was performed with the Euclidean distance and Ward'slinkage methods (Agilent GeneSpring GX). The microarray data have been submitted to NCBI GEO and available under GSE87376.

TCGA analysis

Each 27 microarray data of human GBM and LGG were obtained from TCGA and analyzed for the expression levels of ecrg4, ifna5, ifna14, and ifnb1.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism or Microsoft Excel software. Data were presented if not indicated elsewhere as mean ± SD.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

S.T., K.E., and U.K are employees of ASUBIO pharma Co.,Ltd. The other authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Kazunori Yoshikiyo for technical supports and Dr Atsuto Ogata for providing materials and helpful discussion.

Author contributions

T. Moriguchi designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. S.K. and H.K. contributed to the immune cell experiments. S.K.M. performed the culture cell experiments. T. Miki was involved in interpreting data. S.T., K.E., and U.K. performed Microarray and BioPlex assays and data interpretation. T.K. performed experimental design, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bissell MJ, Hines WC. Why don't we get more cancer? A proposed role of the microenvironment in restraining cancer progression. Nat Med 2011; 17:320-9; PMID:21383745; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Su T, Liu H, Lu S. Cloning and identification of cDNA fragments related to human esophageal cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 1998; 20:254-7; PMID:10920976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Götze S, Feldhaus V, Traska T, Wolter M, Reifenberger G, Tannapfel A, Kuhnen C, Martin D, Müller O, Sievers S. ECRG4 is a candidate tumor suppressor gene frequently hypermethylated in colorectal carcinoma and glioma. BMC Cancer 2009; 9:447; PMID:20017917; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2407-9-447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabatier R, Finetti P, Adelaide J, Guille A, Borg JP, Chaffanet M, Lane L, Birnbaum D, Bertucci F. Down-regulation of ECRG4, a candidate tumor suppressor gene, in human breast cancer. PLoS One 2011; 6:e27656; PMID:22110708; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0027656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vanaja DK, Ehrich M, Van den Boom D, Cheville JC, Karnes RJ, Tindall DJ, Cantor CR, Young CY. Hypermethylation of genes for diagnosis and risk stratification of prostate cancer. Cancer Invest 2009; 27:549-60; PMID:19229700; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/07357900802620794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yue CM, Deng DJ, Bi MX, Guo LP, Lu SH. Expression of ECRG4, a novel esophageal cancer-related gene, downregulated by CpG island hypermethylation in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9:1174-8; PMID:12800218; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3748/wjg.v9.i6.1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li LW, Yu XY, Yang Y, Zhang CP, Guo LP, Lu SH. Expression of esophageal cancer related gene 4 (ECRG4), a novel tumor suppressor gene, in esophageal cancer and its inhibitory effect on the tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. Int J Cancer 2009; 125:1505-13; PMID:19521989; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.24513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Liu X, Zhang B, Qi D, Zhang L, Jin Y, Yang H. Overexpression of candidate tumor suppressor ECRG4 inhibits glioma proliferation and invasion. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2010; 29:89; PMID:20598162; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1756-9966-29-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu T, Xiao D, Zhang X. ECRG4 inhibits growth and invasiveness of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in vitro and in vivo. Oncol Lett 2013; 5:1921-6; PMID:23833667; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3892/ol.2013.1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baird A, Coimbra R, Dang X, Lopez N, Lee J, Krzyzaniak M, Winfield R, Potenza B, Eliceiri BP. Cell surface localization and release of the candidate tumor suppressor Ecrg4 from polymorphonuclear cells and monocytes activate macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 2012; 91:773-81; PMID:22396620; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1189/jlb.1011503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dang X, Podvin S, Coimbra R, Eliceiri B, Baird A. Cell-specific processing and release of the hormone-like precursor and candidate tumor suppressor gene product, Ecrg4. Cell Tissue Res 2012; 348:505-14; PMID:22526622; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00441-012-1396-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirabeau O, Perlas E, Severini C, Audero E, Gascuel O, Possenti R, Birney E, Rosenthal N, Gross C. Identification of novel peptide hormones in the human proteome by hidden Markov model screening. Genome Res 2007; 17:320-7; PMID:17284679; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gr.5755407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozawa A, Lick AN, Lindberg I. Processing of proaugurin is required to suppress proliferation of tumor cell lines. Mol Endocrinol 2011; 25:776-84; PMID:21436262; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/me.2010-0389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hide T, Takezaki T, Nakatani Y, Nakamura H, Kuratsu J, Kondo T. Sox11 prevents tumorigenesis of glioma-initiating cells by inducing neuronal differentiation. Cancer Res 2009; 69:7953-9; PMID:19808959; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishide K, Nakatani Y, Kiyonari H, Kondo T. Glioblastoma formation from cell population depleted of Prominin1-expressing cells. PLoS One 2009; 4:e6869; PMID:19718438; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0006869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tadross JA, Patterson M, Suzuki K, Beale KE, Boughton CK, Smith KL, Moore S, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Augurin stimulates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis via the release of corticotrophin-releasing factor in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2010; 159:1663-71; PMID:20233222; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00655.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee J, Dang X, Borboa A, Coimbra R, Baird A, Eliceiri BP. Thrombin-processed Ecrg4 recruits myeloid cells and induces antitumorigenic inflammation. Neuro Oncol 2015; 17:685-96; PMID:25378632; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/neuonc/nou302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunn GP, Koebel CM, Schreiber RD. Interferons, immunity and cancer immunoediting. Nat Rev Immunol, 2006; 6:836-48; PMID:17063185; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Smyth MJ, Kroemer G. Type I interferons in anticancer immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15:405-14; PMID:26027717; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nri3845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W, Graeber MB. The molecular profile of microglia under the influence of glioma. Neuro Oncol 2012; 14:958-78; PMID:22573310; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/neuonc/nos116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei J, Gabrusiewicz K, Heimberger A. The controversial role of microglia in malignant gliomas. Clin Dev Immunol 2013; 2013:285246; PMID:23983766; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2013/285246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheehan KC, Lai KS, Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Diamond MS, Heutel JD, Dungo-Arthur C, Carrero JA, White JM, Hertzog PJ et al.. Blocking monoclonal antibodies specific for mouse IFN-α/β receptor subunit 1 (IFNAR-1) from mice immunized by in vivo hydrodynamic transfection. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2006; 26:804-19; PMID:17115899; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/jir.2006.26.804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diamond MS, Kinder M, Matsushita H, Mashayekhi M, Dunn GP, Archambault JM, Lee H, Arthur CD, White JM, Kalinke U et al.. Type I interferon is selectively required by dendritic cells for immune rejection of tumors. J Exp Med 2011; 208:1989-2003; PMID:21930769; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20101158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Sheehan KC, Shankaran V, Uppaluri R, Bui JD, Diamond MS, Koebel CM, Arthur C, White JM et al.. A critical function for type I interferons in cancer immunoediting. Nat Immunol 2005; 6:722-9; PMID:15951814; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ni1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuertes MB, Kacha AK, Kline J, Woo SR, Kranz DM, Murphy KM, Gajewski TF. Host type I IFN signals are required for antitumor CD8+ T cell responses through CD8{α}+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2011; 208:2005-16; PMID:21930765; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20101159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita M, Scheurer ME, Decker SA, McDonald HA, Kohanbash G, Kastenhuber ER, Kato H, Bondy ML, Ohlfest JR, Okada H. Role of type 1 IFNs in antiglioma immunosurveillance–using mouse studies to guide examination of novel prognostic markers in humans. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16:3409-19; PMID:20472682; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swann JB, Hayakawa Y, Zerafa N, Sheehan KC, Scott B, Schreiber RD, Hertzog P, Smyth MJ. Type I IFN contributes to NK cell homeostasis, activation, and antitumor function. J Immunol 2007; 178:7540-9; PMID:17548588; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6:24-37; PMID:16397525; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity's roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science 2011; 331:1565-70; PMID:21436444; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1203486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biswas SK, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Tumor-associated macrophages: functional diversity, clinical significance, and open questions. Semin Immunopathol 2013; 35:585-600; PMID:23657835; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00281-013-0367-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep 2014; 6:13; PMID:24669294; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.12703/P6-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meraz MA, White JM, Sheehan KC, Bach EA, Rodig SJ, Dighe AS, Kaplan DH, Riley JK, Greenlund AC, Campbell D et al.. Targeted disruption of the Stat1 gene in mice reveals unexpected physiologic specificity in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Cell 1996; 84:431-42; PMID:8608597; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81288-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheng W, Zong Y, Mohammad A, Ajit D, Cui J, Han D, Hamilton JL, Simonyi A, Sun AY, Gu Z et al.. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and lipopolysaccharide induce changes in cell morphology, and upregulation of ERK1/2, iNOS and sPLA2-IIA expression in astrocytes and microglia. J Neuroinflammation 2011; 8:121; PMID:21943492; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1742-2094-8-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohkuri T, Ghosh A, Kosaka A, Zhu J, Ikeura M, David M, Watkins SC, Sarkar SN, Okada H. STING contributes to antiglioma immunity via triggering type I IFN signals in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Immunol Res 2014; 2:1199-208; PMID:25300859; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.