Abstract

Rodent visual cortex has a hierarchical architecture similar to that of higher mammals (Coogan and Burkhalter, 1993; Marshel et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012). Although notable differences exist between the species in terms or receptive field sizes and orientation map organization (Dräger, 1975; Gattass et al., 1987; Van den Bergh et al., 2010), mouse V1 is thought to respond to local orientation and visual motion elements rather than to global patterns of motion, similar to V1 in higher mammals (Niell and Stryker, 2008; Bonin et al., 2011). However, recent results are inconclusive: some argue mouse V1 is analogous to monkey V1 (Juavinett and Callaway, 2015); others argue that it displays complex motion responses (Muir et al., 2015). We used type I plaids formed by the additive superposition of moving gratings (Adelson and Movshon, 1982; Movshon et al., 1985; Albright and Stoner, 1995) to investigate this question. We show that mouse V1 contains a considerably smaller fraction of component-motion-selective neurons (∼17% vs ∼84%), and a larger fraction of pattern-motion-selective neurons (∼10% vs <1.3%) compared with primate/cat V1. The direction of optokinetic nystagmus correlates with visual perception in higher mammals (Fox et al., 1975; Logothetis and Schall, 1990; Wei and Sun, 1998; Watanabe, 1999; Naber et al., 2011). Measurement of optokinetic responses to plaid stimuli revealed that mice demonstrate bistable perception, sometimes tracking individual stimulus components and others the global pattern of motion. Moreover, bistable optokinetic responses cannot be entirely attributed to subcortical circuitry as V1 lesions alter the fraction of responses occurring along pattern versus component motion. These observations suggest that area V1 input contributes to complex motion perception in the mouse.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Area V1 in the mouse is hierarchically similar but not necessarily identical to area V1 in cats and primates. Here we demonstrate that area V1 neurons process complex motion plaid stimuli differently in mice versus in cats or primates. Specifically, a smaller proportion of mouse V1 cells are sensitive to component motion, and a larger proportion to pattern motion than are found in area V1 of cats/primates. Furthermore, we demonstrate for the first time that mice exhibit bistable visual perception of plaid stimuli, and that this depends, at least in part, on area V1 input. Finally, we suggest that the relative proportion of component-motion-selective responses to pattern-motion-selective responses in mouse V1 may bias visual perception, as evidenced by changes in the direction of elicited optokinetic responses.

Keywords: area V1, bistable stimuli, mouse, plaids

Introduction

A fundamental task faced by the visual system is the computation of global scene motion from the local motion of the parts of the scene (Hildreth and Koch, 1987; Albright and Stoner, 1995). Symmetric additive plaid stimuli have been used in cats and primates to characterize the stage at which visual processing sensitivity to complex motion arises, identifying two distinct populations of neurons (Movshon et al., 1985; Albright and Stoner, 1995). The first population, exemplified by units in cat and primate V1, is orientation and direction selective (Movshon et al., 1985; Gizzi et al., 1990) but is not sensitive to complex motion arising from the interaction of different parts of the scene moving in different directions. The second population of neurons is capable of combining information about the motion of different “elementary” components of the scene. Such neurons are essentially absent from anesthetized primate and cat area V1 (see Figs. 4C, 5C), but start appearing in higher-order thalamic nuclei and extrastriate areas of higher mammals, with the largest populations occurring in areas engaged in visuomotor control and integration [V5/middle temporal area (MT) and medial superior temporal area (MST)] in primates (see Figs. 4D, 5D; Movshon et al., 1985; Rodman and Albright, 1989; Gizzi et al., 1990; Albright and Stoner, 1995; Scannell et al., 1996; Merabet et al., 1998; Khawaja et al., 2009). So, essentially, in higher mammals, pattern-motion (PM) selectivity is generated in extrastriate areas, while V1 neurons are chiefly capable of component-motion-selective responses (but see Guo et al., 2004; and see Discussion).

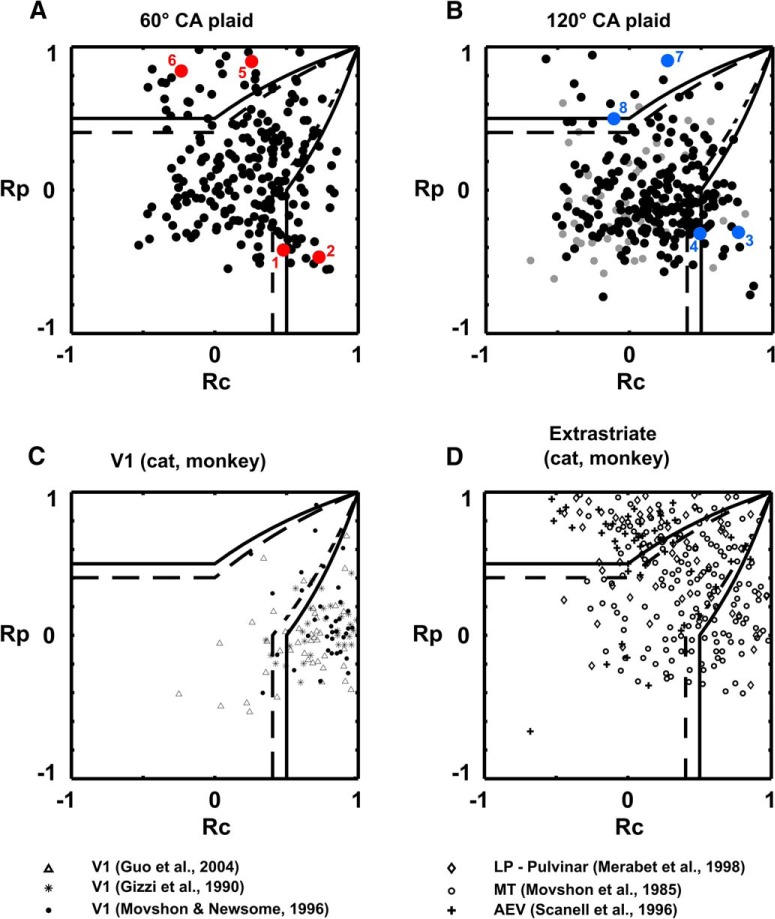

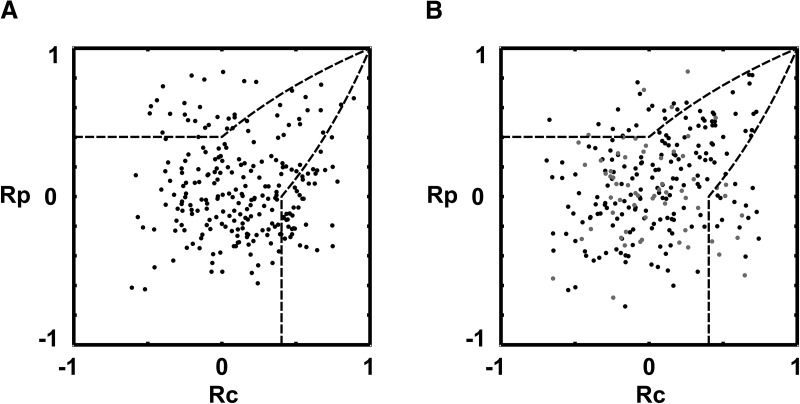

Figure 4.

Component- and pattern-motion selectivity population results. A–D, Scatter plot of component and pattern partial correlation coefficients calculated for each directionally selective L2/3 pyramidal neuron recorded in mouse V1 (A, B), and previous studies in cat/primate V1 (C), and higher visual areas (D), following the study by Smith et al. (2005). The x-axis plots the Rc value for each cell (see Materials and Methods). The y-axis plots the Rp value. Black line boundaries demarcate statistical significance levels calculated from the Fisher transform (see Materials and Methods; Smith et al., 2005): solid black line, p = 0.95; broken black line, p = 0.9. The p = 0.9 value has generally been used by previous investigators (Movshon and Newsome, 1996; Smith et al., 2005). A, Results for the 60° CA plaid. Red dots denote the positions of neurons 1 and 2 (CM-selective responses), and 5 and 6 (PM-selective responses) from Figure 3. Black dots, Data obtained using square-wave gratings and plaids (six animals). B, Results for the 120° CA plaid. Blue dots, Neurons 3 and 4 (CM-selective responses), and neurons 7 and 8 (PM-selective responses) from Figure 3; black dots, data obtained using square-wave gratings and plaids (six animals); gray dots, data obtained using sine-wave gratings and plaids (two animals). C, Literature results from cat and monkey V1 under anesthesia. Data were digitized from the studies by Gizzi et al. (1990), Movshon and Newsome (1996), and Guo et al. (2004). Black filled circles, Monkey V1 (Movshon and Newsome, 1996); stars, cat V1 (Gizzi et al., 1990); triangles, monkey V1, layers 4 and 6 (Guo et al., 2004). Unlike mouse V1 and extrastriate areas of cats and primates, primate and cat V1 under anesthesia contains a large majority of CM-selective neurons with only a small minority of unclassified cells and virtually no PM-selective cells. D, Aggregate population plot of direction-selective cells from cat and monkey extrastriate visual cortical areas and higher-order thalamic nuclei derived from the literature. Data were digitized from the studies by Movshon et al. (1985), Scannell et al. (1996), and Merabet et al. (1998). Open circles, Monkey V5/MT (Movshon et al., 1985); crosses, cat anterior ectosylvian visual area (AEV; Scannell et al., 1996); and rhomboids, cat lateral posterior nucleus of thalamus (LP)–pulvinar complex (Merabet et al., 1998). Note that the shape of the distribution we observe in A and B from mouse V1 is similar to the distributions observed in the extrastriate areas of cats and primates.

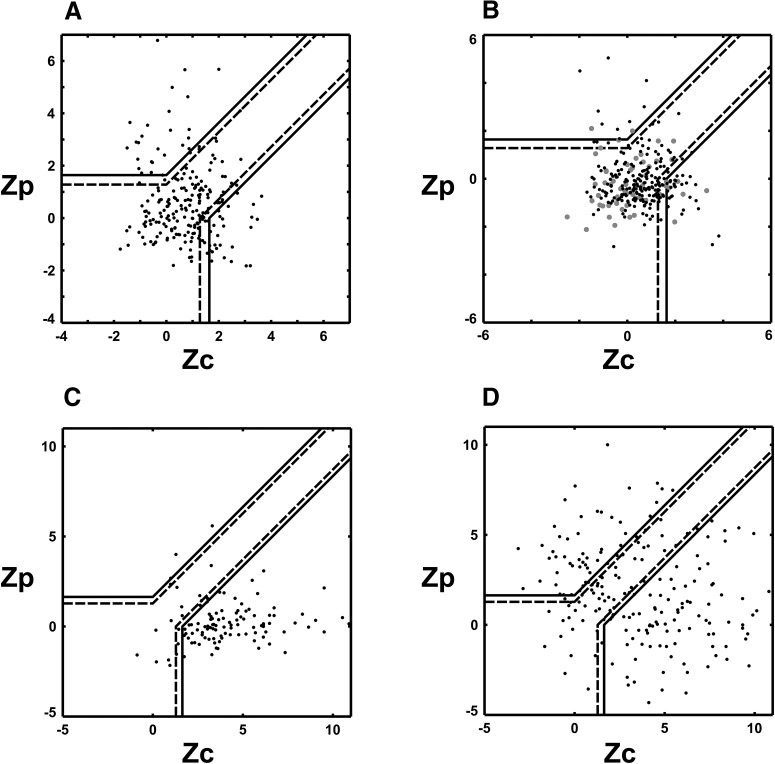

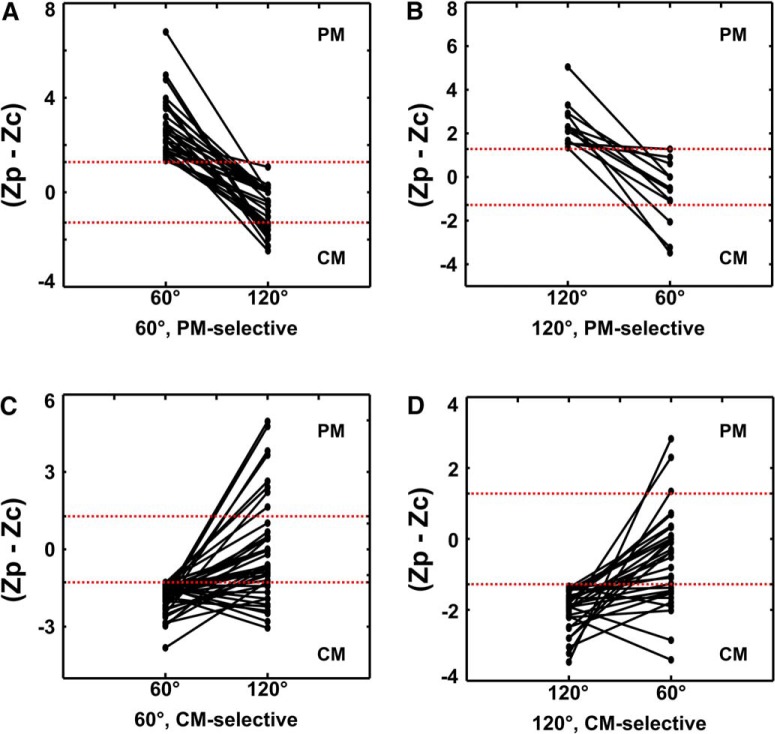

Figure 5.

Component-motion and pattern-motion selectivity population results (z-scores). Scatter plot of component and pattern z-score coefficients calculated for each directionally selective L2/3 pyramidal neuron recorded in mouse V1. The x-axis plots the Zc value for each cell (see Materials and Methods). The y-axis displays the Zp value. Black line boundaries demarcate statistical significance levels calculated from the Fisher transform (see Materials and Methods; Smith et al., 2005): solid black line, p = 0.95; broken black line, p = 0.9. The p = 0.9 value has generally been used by previous investigators (Movshon and Newsome, 1996; Smith et al., 2005). A, Results from the 60° CA plaid, 232 cells pooled from six animals. All data were obtained with square-wave gratings and plaids (black dots). The corresponding plot of partial correlation coefficients is found in Figure 4A. B, Results from the 120° CA plaid. Data obtained with square-wave gratings and plaids are marked with black dots (225 cells pooled from six animals), sine-wave data are marked with gray dots (60 direction-selective cells pooled from two animals). The corresponding plot of partial correlation coefficients is found in Figure 4B. C, Literature results from cat and monkey V1 under anesthesia. Partial correlation data were digitized from the studies by Gizzi et al. (1990), Movshon and Newsome (1996), Guo et al. (2004), and Khawaja et al., 2009; and z-transform was applied to derive z-scores. Unlike mouse V1 and extrastriate areas of cats and primates, primate and cat V1 under anesthesia contains a large majority of CM-selective neurons with only a small minority of unclassified cells and only sporadic PM-selective cells. D, Aggregate population plot of direction-selective cells from cat and monkey extrastriate visual cortical areas and higher-order thalamic nuclei derived from the literature (MT, LS, and LP–pulvinar complex). Partial correlation data were digitized from the studies by Movshon et al. (1985), Gizzi et al. (1990), and Merabet et al. (1998); and were z-transformed to obtain associated z-scores. Note that the population in area V1 behaves more like extrastriate cat and monkey populations than like primate V1. Both primate extrastriate areas and mouse V1 contain large populations of unclassified direction-selective cells (primate extrastriate areas, ∼41%; mouse V1, ∼74%), while primate V1 contains a very small percentage of unclassified cells (∼16%) and most of the direction-selective primate V1 cells are CM-selective (∼84%). Thus, the shape of the distribution we observe in A and B from mouse V1 is more similar to the distributions observed in the extrastriate areas of cats and primates in its spread. The primate V1 distribution, in contrast, is narrowly centered in the CM-selective area of the plot (C).

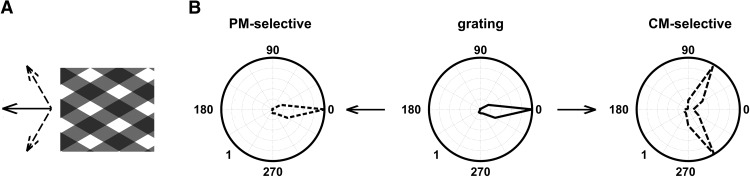

In rodents and lower vertebrates, however, the computations of complex object motion may begin at earlier stages than secondary cortical areas, as early as in retina (Olveczky et al., 2003; Baccus et al., 2008). Compared with cat and primate, mouse V1 is anatomically small, allowing single cells to access information from a larger part of the visual field (Van den Bergh et al., 2010). In principle, this makes global motion computations possible at the first stage of cortical visual processing (Gao et al., 2010). A different scheme of visual motion processing may then occur in mouse visual cortex, where some V1 cells act as complex motion integration units rather than as the narrow orientation and direction-of-motion filters prevalent in cat and monkey V1. To explore this possibility, we measured the response properties of mouse V1 pyramidal neurons to type I symmetric additive plaid patterns (Adelson and Movshon, 1982; Movshon et al., 1985; Albright and Stoner, 1995). Type I symmetric plaid patterns are composed of two component gratings whose directions of motion are symmetric relative to the motion of the global pattern. The angle between component gratings is the plaid cross-angle (CA; Adelson and Movshon, 1982; Movshon et al., 1985; Albright and Stoner, 1995; see Fig. 2A). Cells that respond to the global drift of the intersection pattern (pattern-motion selective) are expected to have similar direction-of-motion tuning curves for both gratings and plaid stimuli (see Fig. 2B, left). In contrast, cells sensitive to the motion of individual component gratings [component-motion (CM) selective] have bilobed tuning curves when tested with plaids (see Fig. 2B, right), since they respond vigorously each time a component grating moves in their preferred direction (Movshon et al., 1985; Albright and Stoner, 1995).

Figure 2.

Stimuli and partial correlation analysis. A, Symmetric (type I) additive square-wave plaids (Adelson and Movshon, 1982; Albright and Stoner, 1995; Guo et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2005). The direction of motion of the global plaid pattern (solid arrow) bisects the angle between the directions of motion of the individual component gratings (dotted arrows). B, Partial correlation model. Middle, Tuning curve elicited by moving gratings (solid black line). Left, Predicted tuning curve for the 120° CA plaid in case of PM-selectivity (dotted black line). Right, Predicted tuning curve for the 120° CA plaid in case of component-motion selectivity (CM-selectivity, dotted black line).

Materials and Methods

Methods summary.

We used C57BL/6 mice, expressing Td-Tomato in Dlx5/6-positive interneurons (Madisen et al., 2010; Miyoshi et al., 2010) in an Oregon-Green-Bapta-1-AM (OGB) set of experiments, and C57BL/6 mice expressing GCaMP6s in cortical neurons for an interlayer comparison set of experiments (Tronche et al., 1999; Madisen et al., 2015). All animals were male. Windows, 3 mm in diameter, were placed over V1. OGB with SR-101 (Stosiek et al., 2003) were injected 2.5–3 mm lateral from midline and 1–1.5 mm anterior to the transverse sinus (Fig. 1A). Layer 2/3 (L2/3) cells 120–200 μm below the pia were imaged at 3.5–7.5 Hz using a Prairie Ultima-IV two-photon microscope fed by a Chameleon Ti:sapphire laser [820 nm, 20×, 0.95 numerical aperture (NA) objective, Olympus; maximum intensity at sample, <50 mW). Isoflurane 0.6% was used for anesthesia. We presented visual stimuli monocularly on an LCD monitor (Dell) covering 60° × 80° of the contralateral visual field. Visual stimuli consisted of drifting square-wave gratings (2 Hz, 0.05 cycles/°) and additive plaid patterns, which were constructed by summing two component gratings at 60° or 120° CA and normalizing for contrast (Smith et al., 2005). Stimulus presentation trials lasted 5 s (2 s, stimulation; 3 s, uniform illumination; 180–360 trials were acquired per stimulus type; grating, 60° CA plaid or 120° CA plaid). The mean luminance was constant throughout. We covered the nonstimulated eye with black foil. Image analysis used custom MATLAB routines and ImageJ (Abràmoff et al., 2004). Following xy-plane motion correction, we defined cell regions of interest (ROIs) and expressed calcium signals as relative fluorescence changes (dF/F) corresponding to mean fluorescence from all pixels inside specific ROIs. Responses were measured either as the integral of calcium events with amplitude >3 SDs above noise, or as relative spike rates after deconvolution (Vogelstein et al., 2010). Either choice produced similar tuning curves (Fig. 1D,E; see Fig. 3). We calculated the direction selectivity index (DSI; Rochefort et al., 2011) for grating stimulation. To classify directionally selective (DSI, >0.5) cells as PM- or CM-selective, we used partial correlation analysis followed by the Fisher z-transform (Smith et al., 2005; see Figs. 4A,B, 5A,B). Current-clamp recordings were obtained with a Heka EPC-10 USB amplifier following the study by Margrie et al. (2002). We recorded optokinetic responses to gratings and plaids in eight head-posted mice (60° CA plaid, n = 8; 120° CA plaid, n = 8) with an infrared camera (model GC660, Allied Vision Technologies) and histogrammed the distribution of optokinetic nystagmus (OKN) directions.

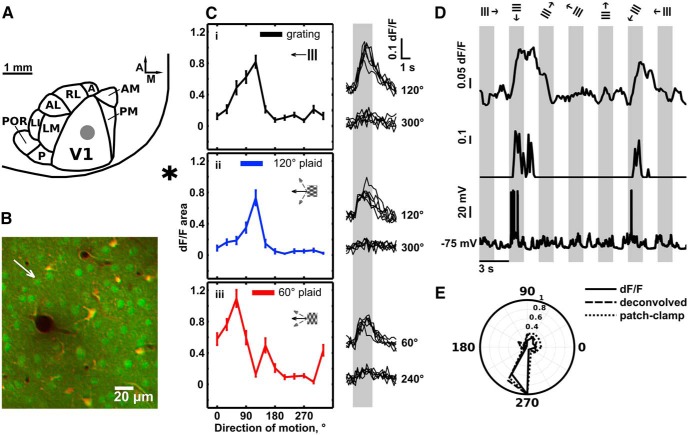

Figure 1.

Direction selectivity of pyramidal cells in mouse V1. A, Position of OGB injection and imaged area in the V1 of the left hemisphere. Typical range of dye injections is denoted by gray circle (2.5–3 mm lateral from midline, 1–1.5 mm anterior to transverse sinus). Position and average layout of area V1 and belt visual areas are adapted from Wang and Burkhalter (2007) and Marshel et al. (2011). A, Anterior; M, medial. We targeted injections to central V1. Star denotes the position of midline (medial) and the location of transverse sinus (posterior to V1). Scale bar, 1 mm. B, Typical in vivo two-photon image of L2/3 neurons in area V1. Green, OGB-filled cells; orange, astrocytes and Td-Tomato-expressing interneurons. White arrow denotes the cell body of the neuron from C. C, Example tuning curves (left) and responses (right) of the directionally selective pyramidal cell in response to drifting gratings and plaid patterns. We obtained tuning curves shown by calculating the mean area under the calcium transients evoked by stimuli with different directions of motion. Gray box in right panels signifies the stimulus presentation time. Ci, Tuning curve elicited by moving gratings. Right, Single-trial responses to the preferred stimulus (120°, top curves), and to a stimulus moving in the opposite direction (300°, bottom curves). Cii, Tuning curve (blue) elicited by a moving plaid with 120° CA. Right, Single-trial responses to the preferred plaid stimulus (120°), and a plaid stimulus moving in the opposite direction (300°, bottom curves). Ciii, Tuning curve (red) elicited by a moving plaid with 60° CA. Right, Single-trial responses to the preferred plaid stimulus (60°, top curves), and stimulus moving in the opposite direction (240°, bottom curves). Inset calibration: 0.1 (10%) dF/F, 1 s. Error bars: mean ± SEM. D, Deconvolution of calcium dF/F signals to compute relative firing rates (Vogelstein et al., 2010). Top, dF/F computed from OGB-1 signals. Middle, Corresponding deconvolved (Vogelstein et al., 2010) normalized mean firing rates. Bottom, corresponding current-clamp recording of spiking activity of the patched neuron. E, Tuning curves normalized to peak response, obtained from dF/F data (solid black line), current-clamp data (dotted black line) and deconvolved data (broken black line) from the cell in D. Note the high degree of correspondence between the tuning curves of each measure. The high correspondence between the OBG-based tuning curves and action potential-based tuning curves is expected, as calcium signals do not reach saturation for the range of recorded action potentials, which were generated in response to the stimuli that we used.

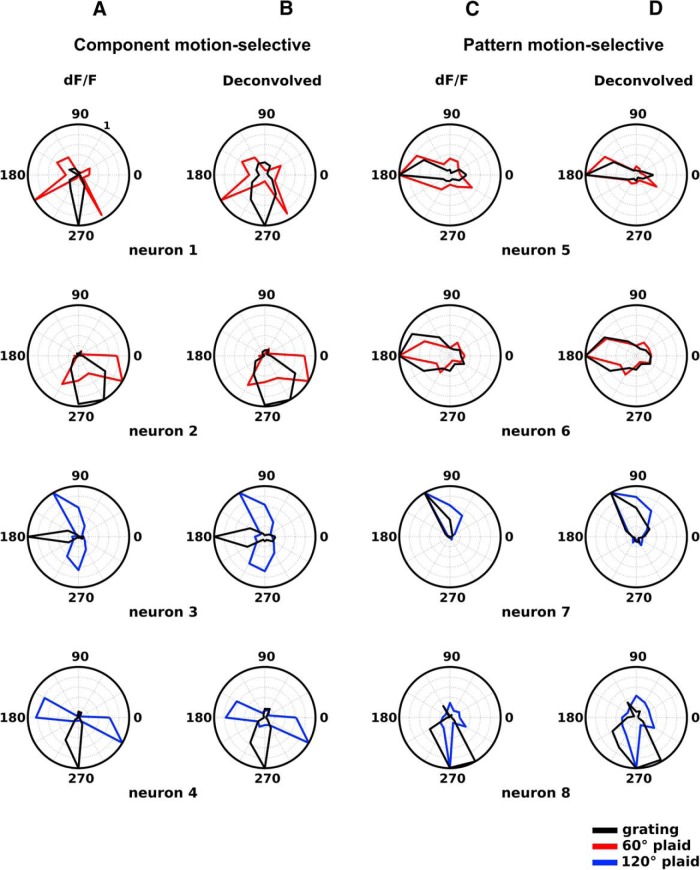

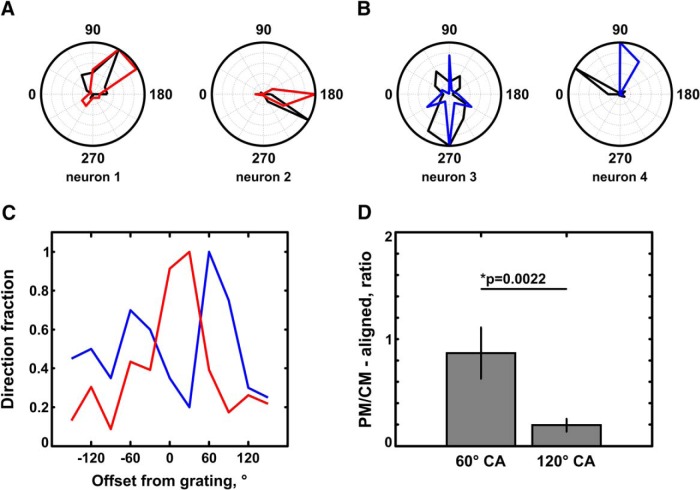

Figure 3.

Examples of component-motion-selective and pattern-motion-selective pyramidal cells: dF/F data vs deconvolved calcium data. A, B, CM-selective cells. C, D, PM-selective cells. A, C, Normalized tuning curves, obtained from dF/F calcium data. B, D, Normalized tuning curves, obtained from deconvolved calcium data. Note the close correspondence between tuning curves obtained from dF/F data and deconvolved data. Black, Tuning curves obtained with moving gratings; red, tuning curves obtained with 60° CA plaids; blue, tuning curves obtained with 120° CA plaids. Neurons 1–4 (A, B) are CM-selective. Note that the bilobed tuning curves generated by plaids have peaks offset from the direction of pattern motion by approximately half of the CA of the plaid (30° for neurons 1 and 2; 60° for neurons 3 and 4). Neurons 5–8 (C, D) are PM-selective and have unimodal direction of motion-tuning functions that match closely for gratings and for plaids.

Animals and surgery.

All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with institutional and federal animal welfare guidelines, and were approved by the Baylor College of Medicine institutional animal care and use committee. For OGB experiments, we used C57BL/6 mice expressing Td-Tomato in Dlx5/6-positive interneurons (Madisen et al., 2010; Miyoshi et al., 2010). The mice were produced by crossing the Ai9 mice, carrying a targeted insertion into the Gt(ROSA)26Sor locus with a loxP-flanked STOP cassette preventing transcription of a CAG promoter-driven red fluorescent protein variant (td-tomato; Madisen et al., 2010), and Dlx5/6-Cre mice, carrying a Cre-recombinase gene, expressed under the Dlx5/6 promoter (The Jackson Laboratory; Miyoshi et al., 2010). Offspring mice, carrying both the flox-stopped td-tomato and Cre, express Td-Tomato in ∼65% of interneurons originating from the lateral geniculate eminence.

Mice for GCaMP6s experiments were produced by crossing Ai96 GCaMP6s reporter mice (Madisen et al., 2015) to Nestin-Cre mice, expressing Cre-recombinase under nestin promoter (Tronche et al., 1999); both mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. Offspring mice, carrying both the flox-stopped GCaMP6s and Cre, express GCaMP6s in cortical and peripheral neurons. Mice were reared in a 12 h dark/light cycle until 2–3 months of age and subsequently were used for recordings. During surgery, mice where anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, which was delivered in pure oxygen via tubing near the nose of the animal. Local anesthesia with lidocaine (2%) was given under the skin and on the skull. We placed a 3 mm round craniotomy above V1 (Fig. 1A), and, for OGB experiments, pressure injected 1 mm OGB with 100 μm SR-101 dissolved in Pluronic via a glass pipette 200 μm below the dura (Stosiek et al., 2003). All injection sites were located 2.5–3 mm lateral from midline and 1–1.5 mm frontal to the transverse sinus, placing them squarely in the central area V1 (Wang and Burkhalter, 2007; Marshel et al., 2011; Fig. 1A). After injection, we fixed a glass coverslip above V1 with Vetbond glue. We kept eyes moisturized using a topical eye ointment (polydimethylsiloxane-200, Sigma-Aldrich). One hour after injection, we reduced the isoflurane level to 0.6% and performed two-photon calcium imaging.

Visual stimulation for the two-photon experiments.

We constructed visual stimuli using the MATLAB Psychophysics Toolbox (www.psychtoolbox.org). We used drifting square-wave gratings with a temporal frequency of 2 Hz and a spatial frequency of 0.05 cycles/°. These parameters were selected because they were previously demonstrated to be optimal for the larger portion of neurons in rodent V1 (Ohki et al., 2005; Niell and Stryker, 2008; Gao et al., 2010). Additive plaid patterns were constructed by summing up component gratings of 50% contrast (Smith et al., 2005). We used plaid patterns for which the cross-angle between gratings was 60° or 120°. Each visual presentation trial lasted 5 s: 2 s of visual stimulus presentation, followed by 3 s of spatially uniform illumination. We kept mean luminance constant throughout both the background and the stimulation periods. We presented stimuli on a flat LCD monitor (Dell), which was located 27 cm from the mouse eye, and covering 60° × 80° in the contralateral monocular visual field. Presentation was monocular. We covered the nonstimulated eye with black foil during the experiment.

Two-photon imaging.

We used a Prairie Ultima-IV two-photon microscope with custom modifications, fed by a Chameleon Ti:sapphire Ultra-II laser and equipped with two Hamamatsu photomultiplier tubes. PrairieView software (version 4.1.1.4) was used to control the laser and collect images (Prairie Technologies). We imaged cells 120–200 μm below the pia, in layer 2/3 of mouse V1. The laser was set at a wavelength of 820 nm. At this wavelength, red fluorescing cells were either Td-Tomato-expressing interneurons or SR-101-stained astrocytes. We selected cells that did not display red fluorescence and, therefore, were identified as pyramidal neurons. We selected an ROI containing 50–320 cells for imaging and acquired images using a 20× objective lens (0.95 NA water-immersion, Olympus) at acquisition speeds ranging from ∼3.5 to 7.5 Hz, depending on ROI size. For GCaMP6s imaging, we used a 16× water-immersion objective, the laser wavelength was set to 920 nm, and the acquisition speed was set at 6.5–7.5 Hz. Typically, we collected six to eight 15-min-long movies from each region of interest. Each movie was followed by a rest period of 15–30 min, during which the monitor remained at uniform illumination to maintain mean light level adaptation.

Patch-clamp recordings.

Whole-cell and loose-patch recordings were obtained with a Heka EPC-10 USB amplifier in current-clamp mode using standard techniques (Margrie et al., 2002). Briefly, 6–8 MΩ glass pipettes filled with an intracellular solution (in mm: 105 K-gluconate, 30 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 phosphocreatine, 4 ATP-Mg, and 0.3 GTP, adjusted to 290 mOsm and pH 7.3 with KOH, containing 10 μm Alexa Fluor-594 or tetramethylrhodamine dextran; Invitrogen) were advanced under two-photon visual guidance, initially with ∼100 mbar pressure, then ∼40 mbar when ∼50 μm under the dura. We reduced pressure to ∼20 mbar when approaching a cell. Once resistance increased to ∼150% of the initial value, laser scanning was stopped and up to 200 mbar negative pressure was applied, until the resistance increased up to 200 MΩ. When successful, a gigaohm seal was typically formed within 2 min. The pipette was retracted carefully by a few micrometers to avoid penetration of the interior compartments of the cell during break-in. Then ∼200 ms pulses of negative pressure (starting at −10 psi and increasing gradually) were applied via a Picospritzer with a vacuum module until the patch of membrane was broken. Fast pipette capacitance was neutralized before break-in, and slow capacitance was neutralized afterward.

Calcium imaging data analysis.

We performed image analysis off-line in several steps, using custom-written MATLAB routines and ImageJ (Abràmoff et al., 2004). For OGB-1 data, we first applied motion correction to remove slow drifts on the x–y-plane, using cross-correlation between subsequent frames of the movies, containing red (Td-Tomato- and SR-101-based) fluorescent signals. After motion correction, we used ImageJ software to draw the ROIs of cells around cell body centers, staying 1–2 pixels from the margin of a cell to avoid contamination from neuropil signals. We then averaged the signals of cell ROI pixels and converted them into dF/F. For GCaMP6s data, we used custom-written MATLAB software obtained from Tsai-Wen Chen (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Janelia Research Campus, Ashburn, VA) to perform image segmentation and extract signals from doughnut-shaped cell bodies frame by frame (since GCaMP6s is excluded from the nucleus of the cells, at low expression levels the cell bodies appear doughnut shaped). We also used this software to extract signals from dendritic sections. Cell and dendritic ROI transients were accepted as firing events when their amplitude exceeded 2 SDs of prestimulus activity, which was calculated over a period of 1 s immediately before the stimulus onset. We estimated the response of each cell to the stimulus by the integral of the dF/F calcium transients evoked during the stimulus presentation period (from 0 to 2 s after stimulus onset) and averaged across similar stimulus trials (dF/F area; mean of 15–30 trials). In a separate analysis, we deconvolved dF/F signal time courses using the algorithm of Vogelstein et al. (2010), thereby converting the calcium signal from each neuron to inferred, relative spike rates. These were then compared between visual stimulation and uniform illumination periods. Similar tuning curves were obtained when using either dF/F signal or the deconvolved data to estimate the response of the neurons (Fig. 1D,E; see Fig. 3).

Direction selectivity index.

We evaluated the selectivity of each cell for the direction of motion using the DSI, as follows:

where Dpreferred is the response to motion in the preferred direction of the cell, and Dopposite is the response to motion in the opposite direction. Highly selective cells have a DSI value near 1, while a 3:1 response difference would result in a DSI value of 0.5. Neurons with DSI of >0.5 when stimulated with moving gratings and responsive to at least one of the plaids were selected for partial correlation analysis. Tuning width was estimated by fitting the dominant peak with a Gaussian and estimating the half-width of the fitted curve at half-height.

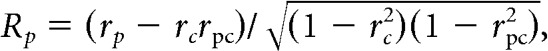

Partial correlation analysis for classifying cells as PM-selective versus CM-selective.

Cells that were responsive for at least one of the plaids and showed direction selectivity for the drifting gratings were subjected to partial correlation analysis (Smith et al., 2005) to determine whether their responses were more consistent with CM-selectivity or with PM-selectivity. Following the findings of Smith et al. (2005), we used the grating tuning curve of each cell to construct two extreme-case predictions for the response of the cell to a drifting plaid, as follows: (1) a prediction corresponding to an exclusively CM-selective cell; and (2) a prediction corresponding to an exclusively PM-selective cell (Fig. 2B). The prediction for PM-selectivity corresponds to the tuning curve obtained with gratings (Fig. 2B, left and middle). The prediction for CM-selectivity is built by averaging the tuning curve of the cell for grating rotated left and right by the offset angle of the plaid components (Fig. 2B, right). Next, we calculated the linear Pearson correlation coefficient between the actual tuning curve of each cell obtained with a plaid and the PM- and CM-selective tuning curve predictions for the cell (rp and rc, respectively) for the same plaid. Then we calculated partial correlation coefficients (PM-selective response (Rp) and CM-selective response (Rc), respectively) by adjusting for the correlation between predictions, as follows:

|

|

where rc is the linear Pearson correlation coefficient between the CM-selective prediction and the actual plaid tuning function, rp is the linear Pearson correlation coefficient between the PM-selective prediction and the actual plaid tuning function, and rpc is the linear Pearson correlation between the PM- and CM-selective predictions. To rate the selectivity for pattern versus component motion of each cell, we applied a version of the Fisher z-transform (Smith et al., 2005) to calculate the associated z-scores, as follows:

where n (12 in our case) is the number of points in the correlation (i.e., the number of different directions used to measure direction-of-motion tuning curves), and (n − 3) is the number of degrees of freedom. We adopted a 95% confidence threshold, corresponding to a z-score difference of 1.645 as a measure of significant difference between pattern z-score (Zp) and component z-score (Zc) values. If the Zp value of a cell was greater than Zc value of the cell or 0 (whichever is greater) by 1.645, we classified the response of the cell as PM-selective. Analogously, if the Zc value of a cell was greater than the Zp value or 0 (whichever is greater) by 1.645, the response of the cell was classified as CM-selective. Cells that did not meet these criteria remained unclassified. To compare with prior studies in cats and primates (Gizzi et al., 1990; Movshon and Newsome, 1996; Smith et al., 2005), we repeated the classification with the 90% confidence threshold (significant z-score difference, 1.28) used there. This threshold did not affect the general conclusions of our study.

Unimodal unclassified cells.

To identify unimodal unclassified cells for further analysis, we selected cells that satisfied all of the following criteria: (1) the cell showed direction selectivity for drifting gratings (single peak tuning curve; DSI = >0.5; as defined in Materials and Methods, Direction selectivity index) and also generated above-noise responses for the plaids of the specific cross-angle (60° and/or 120°); (2) the responses for the plaids are either single peaked or double peaked with opposite peaks, and the monodirectional cells were evaluated by plaid DSI (pDSI), which is computed in the same way as the direction-selectivity index for the gratings, as follows:

where Dpreferred is the response for motion to the preferred plaid direction of the cell, and Dopposite is the response for motion to the opposite direction. Highly selective cells have a pDSI value near 1, while a 3:1 response difference would result in a pDSI value of 0.5.

Bidirectional responses to plaids were evaluated by the bi-DSI (bDSI), which is computed the same way that the orientation selectivity index is computed for the gratings, as follows:

where Dpeak is the direction axis along which peak responses occur, while Dorth is the direction axis orthogonal to the peak response axis.

If the cell had both bDSI and pDSI values of >0.5, it was accepted as monodirectional, and if cell had only a bDSI value of >0.5, it was accepted as bidirectional.

Next, we looked at how the peak or peaks of the tuning curve of the cell for the plaid related to the tuning curve peak of the grating. A monodirectional cell was considered to be pattern-motion aligned if its tuning curve peak of the plaid exactly coincided or was exactly opposite to the tuning curve peak of the grating. A bidirectional cell was considered to be pattern-motion aligned if either one of its peaks for the tuning curve of the plaid was aligned with the peak of the grating. A cell was considered to be component-motion aligned if its tuning curve for the plaid had a peak rotated in relation to the grating tuning curve peak by half of the cross-angle of the plaid (i.e., pointing along one of the plaid components).

Optokinetic nystagmus.

We recorded nystagmoid responses to drifting gratings and plaids in 8 C57BL/6 head-posted mice. The stimulus was presented on three screens, positioned around the mouse to cover ∼270° of the visual field of the mouse (see Fig. 8A,B). The center of each screen was located at ∼27 cm from the mouse. Stimulus parameters were identical to the ones used for two-photon experiments. We used an infrared camera (model GC660, Allied Vision Technologies) to record the movements of the right eye at 60 Hz. We analyzed 10- to 20-min-long movies off-line with custom MATLAB code to determine the position (center of mass) of the pupil relative to the position (center of mass) of the reflection of the infrared light source on the surface of the cornea (see Fig. 8C). Optokinetic eye movement (EM) is composed of smooth pursuit following stimulus drift, followed by rapid saccade in the direction opposite to the direction of global stimulus drift. This pattern of movements [slow pursuit phase plus rapid saccade phase repeats as long as the stimulus (drifting grating or plaid) is present]. For relatively small EMs, the distance between the center of the pupil and the corneal reflection is proportional to the frontal projection of the angular deflection of the eye (Sakatani and Isa, 2004; Cahill and Nathans, 2008). We analyzed both vertical and horizontal EM components. Periods containing eye-blink artifacts were removed. EMs consisting of slow pursuit movement in the direction of the drift of the global stimulus ±89° and preceded by a saccade in a direction opposite to the drift of the global stimulus ±89° were selected for further analysis. We applied linear fit to the slow-pursuit phase of each EM, and EMs with r2 > 0.5 were accepted for further analysis. We determined the direction of each accepted EM by comparing the amplitude of horizontal and vertical saccade projections of components. We compensated for the inherent difference in gain between vertical and horizontal OKN by measuring the relative mean saccade amplitude for horizontal versus vertical drifting gratings. Typically, the vertical OKN amplitudes were, on average, smaller than the horizontal OKN amplitudes by a factor of ∼1.5. Then we used the ratio of horizontal to vertical saccade amplitude to adjust the amplitude of the vertical component of OKN elicited by plaid stimuli. We then histogrammed the directions of EMs from [−89°, 89°], where 0° corresponds to the horizontal direction (which is also the direction of the drift of the global stimulus; see Fig. 8J). For the plaid-induced OKN, we classified each EM as component or pattern aligned. For this, we first determined the width of the distribution of EM angles evoked by horizontally drifting gratings. We used 1 SD from the mean (typically located at 0) as the threshold for pattern-aligned EM angles. Thus, any EM whose angle exceeded this threshold was classified as component aligned, while EMs with angles inside the [−STD, +STD] interval are pattern aligned. To study the dynamics of OKN alternation between following the global pattern drift or component motion, we cut out the periods of the stable OKN (at least three saccade–pursuit pairs, occurring without break between the pairs; e.g., saccadic movement is immediately followed by the pursuit phase of the next pair). In each period, we determined the duration that was occupied by the persistent tracking of global pattern versus the duration that was occupied by the persistent tracking of component gratings before the alternation occurred, or the OKN period ended. Then we determined the durations of “coherent” and “transparent” OKN phases and their fraction out of the total duration of OKN.

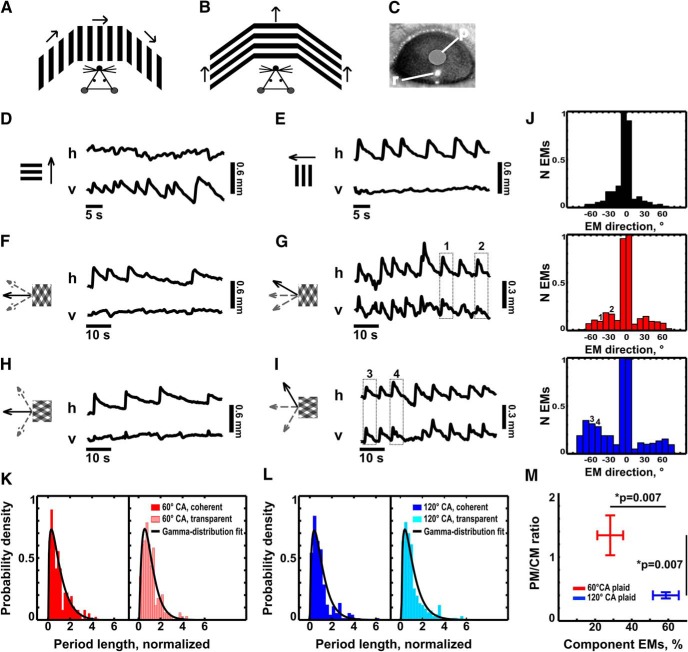

Figure 8.

Mice exhibit bistable OKN responses. A, B, Experimental setup. We presented the stimulus on three screens positioned at equal distances around the mouse head to cover ∼270° of the mouse visual field. We headposted the mouse to hold its head still and monitored EMs with an infrared camera (see Materials and Methods). Arrows, Direction of the drift of the stimulus. A, Setup for the recording of horizontal OKN. B, Setup for the recording of vertical OKN. C, Infrared image of a mouse eye. r, Reflection; p, pupil. D, Example of OKN elicited by a horizontally oriented grating drifting in the vertical direction (upward), as shown in B. v, Vertical eye position; h, horizontal eye position. As expected, OKN movements contain a clear vertical component, with no consistent horizontal deflections. E, Example of OKN elicited by a vertically oriented grating drifting in the horizontal direction, as shown in A. v, Vertical eye position; h, horizontal eye position. As expected, OKN movements contain solely a horizontal component, with no consistent vertical deflections. F, Example of OKN elicited by a 60° CA plaid whose global pattern is drifting in the horizontal direction. In this case, the eyes of the mouse follow the direction of motion of the global plaid pattern (horizontal), as is evident from the absence of a vertical OKN component. G, OKN elicited by the same 60° CA plaid as in F. In this case, the eyes of the mouse follow the direction of one of the component gratings of the plaid (the one moving toward 150°), as is evident from the combination of appropriate vertical and horizontal OKN movements. H, Example of OKN elicited by a 120° CA plaid whose global pattern is drifting in the horizontal direction. As in F, the mouse eye movements show purely horizontal OKN aligned with the direction of motion of the global plaid pattern. I, Example of component OKN, elicited by the same 120° CA plaid, as in H. In this case, the eye of the mouse follows one of the component gratings of the plaid (the one moving toward 120°). J, Normalized histograms of the direction of nystagmoid EMs elicited by gratings and plaid stimuli, which are expressed as offsets from the horizontal OKN elicited by the vertically moving grating described in C. Black histogram (top, data from eight animals), EMs elicited by the vertically oriented horizontally moving grating; red histogram (middle, data from eight animals), EMs elicited by the 60° CA plaid, whose global pattern is moving in the horizontal direction; blue histogram (bottom, data from 8 eight animals), EMs elicited by the 120° CA plaid, whose global pattern is moving in the horizontal direction. Note that, as the cross-angle of the plaid increases, the histogram becomes trimodal, with one peak corresponding to the pattern motion, and the other two peaks to motion of the components of the plaid. When there is only a grating stimulus (top) the directions of OKN are clustered tightly around 0° (mean ± SD = −3.2 ± 19.5°; median = 0). In contrast, for the 60° CA plaid a considerable fraction (∼28%) of nystagmoid EMs lie beyond 1 SD from the central peak (at 0°), corresponding to OKN elicited by either one or the other of the plaid components. For the 120° CA plaid, component perception becomes more pronounced as ∼58% of nystagmoid EMs belong to the secondary modes (±1 SD from the central peak at 0°). These modes have peaks at 49 ± 17.9° and −54.5 ± 15.7° (mean ± SD), respectively, approximately corresponding to the directions of drift of the 120° CA components of the plaid. K, Distribution of durations of the periods of coherent (red histogram) versus transparent (pale-red histogram) motion perception induced by the 60° plaid (eight mice; 175 transparent periods and 181 coherent periods). Before pooling, the dataset of each animal was normalized by its mean duration. Coherent, Red; transparent, pale red. The distributions were fit with gamma distribution (coherent, p = 0.017; transparent, p = 0.031; χ2 test). L, Distribution of durations of the periods of coherent (blue histogram) vs transparent (cyan histogram) motion perception induced by the 120° plaid (eight mice; 264 transparent periods and 258 coherent periods). Before pooling, the dataset of each animal was normalized by its mean duration. Coherent, Blue; transparent, cyan. The distributions were fit with gamma distribution (coherent, p = 0.000018; transparent, p = 0.00005; χ2 test). M, The increase in angle between the plaid components correlates with an increase in the relative fraction of transparent OKN, and with a shift in the ratio between PM-selective and CM-selective neuronal responses in favor of CM-selectivity. Error bars represent the SEM. Red, 60° CA plaid data; blue, 120° CA plaid data. Two-photon data, n = 6 animals; EM analysis, n = 8 animals. Significance testing across animals: Wilcoxon rank-sum test: p = 0.007 for PM/CM ratio shift and component EM fraction change.

Optokinetic nystagmus under V1 lesions.

Unilateral V1 lesions were made in seven Dlx 5/6-Cre mice, expressing Td-Tomato in a subset of interneurons. The lesions (lesion size: coronal plane, 0.8–1.8 mm; sagittal plane, 1.5–1.8 mm; located approximately in the center of the V1) were induced by photocoagulation under visual two-photon guidance, using a laser with a wavelength of 810 nm. The location and extent of the lesions within the V1 were verified by Nissl staining of brain sections (60 μm thick) after the experiment in three animals (see Fig. 9A,B). Optokinetic responses were measured before and after the lesion in both the contralateral (lesion-affected) and ipsilateral eye (see Fig. 9C). Ipsilateral eye measurements served as an internal control for the contralateral eye. OKN in mice is asymmetric, and responses are driven by the eye receiving the temporonasal stimulation. Because of this, we adjusted the global direction of the stimulus so that the recorded eye was always receiving temporonasal stimulation (see Fig. 9C). Four animals received monocular stimulation, with stimulus running on two screens covering 180° of visual space (see Fig. 9C). Three animals received binocular stimulation, as shown in Figure 8A. The monocular and the binocular results were pooled together for statistical assessment, as the general direction of change did not differ between the two conditions.

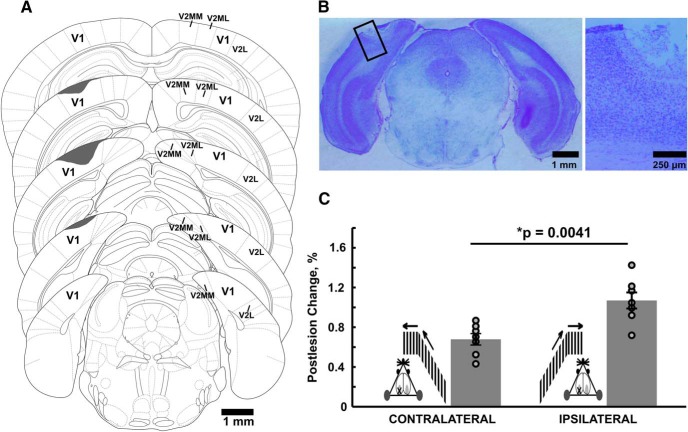

Figure 9.

V1 lesions alter bistable optokinetic responses. A, Lesion location in the V1 (shaded areas, one mouse). The slice schematics are adapted from the atlas of the mouse brain by Paxinos and Franklin (2001), and lesion position is derived from Nissl-stained brain sections. Lesioned areas are shaded in gray. The 60 μm slices are shown at ∼600 μm intervals from each other. Across mice, the maximal lateral width of the lesion in V1 was between 0.8 and 1.8 mm. Sagittally, the lesions extended between 2.7 and 4.5 mm caudal to the bregma. B, Left, Nissl-stained coronal section of the mouse brain (∼4 mm caudal to the bregma), showing the lesion in V1. Box, Lesioned area, shown on the right; right, lesion position in the cortical thickness. C, The effect of the unilateral V1 lesion on the OKN responses recorded from contralateral versus ipsilateral eyes (to the lesion). The percentage of component-aligned eye movements recorded from each eye before and 3–25 d after the lesions were compared. Insets show the stimulus arrangement for monocular stimulation (see also Materials and Methods). Crosses mark the V1 containing the lesion. Left column, Contralateral eye stimulation and recording; right column, ipsilateral eye stimulation and recording. Dots stand for individual data points. After the lesion, when the contralateral eye was driving the OKN, the percentage of component-aligned eye movements decreased consistently in all examined animals. If ipsilateral eye stimulation was driving the OKN, the percentage of component-aligned eye movements mostly showed small changes, and the direction of those changes was inconsistent across the animals. Bars, Relative change of the fraction of component-aligned eye movements for ipsilaterally and contralaterally driven OKN after the lesion, with data from across seven animals (mean ± SEM); ipsilateral OKN, 1.07 ± 0.09; contralateral OKN, 0.68 ± 0.06. While there was a significant overall decrease in the fraction of component-aligned movements in contralaterally driven OKN, the ipsilaterally driven OKN properties on average did not change across seven animals (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p = 0.0041, n = 7).

Statistical tests.

For comparisons of the ratio of PM-selective/CM-selective responses and the fraction of component EMS, we used the two-tailed paired t test and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to account for the small sample size (six to eight animals). A paired Wilcoxon rank-sum test was also applied to assess the changes in OKN properties after the V1 lesion. To estimate the goodness of fit for the gamma distribution fitting of OKN bistability periods, we used a χ2 test. The statistical significance of cell classification as pattern-motion selective or component-motion selective was ascertained by applying bootstrapping to the existing tuning curves. To do this, we constructed 1000–2000 surrogate tuning curve pairs (grating–plaid) by randomly drawing and averaging 10–15 single-trial responses from the pool of single-trial responses for each condition and for each direction drift (two conditions, 12 directions/condition, 15–30 trials/direction). The resulting surrogate tuning curve pairs were then assigned a z-score difference value by partial correlation analysis and Fisher transform, just like real tuning curve pairs (see Materials and Methods, Partial correlation analysis). This resulted in the distribution of the z-score difference values for each cell (1000–2000 values/distribution). We then determined whether the real z-score value of each cell fell within the 0.95 confidence interval of the distribution. If the real z-score value of the cell was found to be outside of the 0.95 confidence interval, such a cell was removed from analysis. In addition, we determined whether a significant number of z-scores in the bootstrapped distribution of the cell (>5%) fell into the category opposite to the one assigned at the classification of real tuning curves (i.e., if the cell was classified as PM-selective, we determined whether >5% of the bootstrapped z-score differences were in fact indicative of CM-selectivity; z < −1.28). Cells meeting this criterion were also removed from the analysis.

Results

Pyramidal neurons show direction-selective responses for both drifting gratings and two-dimensional moving plaids

We tested 1119 pyramidal neurons from six animals in L2/3 of mouse V1 using square-wave gratings and plaid stimuli with 60° and 120° CAs. We used standard stereotaxic coordinates to place cranial windows over mouse V1 (Fig. 1A) and used two-photon imaging with OGB to record neuronal responses under light (0.6%) isoflurane anesthesia (see Materials and Methods; Fig. 1B). A total of 60.6% of recorded pyramidal cells (678) were visually responsive [i.e., generated above-noise (>3 SDs) responses for at least one visual stimulus]. Figure 1C illustrates a representative example of stimulus-driven dF/F calcium responses, and tuning curves elicited with gratings (black), 60° CA plaids (red), and 120° CA plaids (blue). Relative firing rates were extracted from the calcium signal using a well validated deconvolution algorithm by Vogelstein et al. (2010; Fig. 1D). Figure 1E and Figure 3 illustrate the excellent correspondence between tuning functions calculated from dF/F calcium data, deconvolved firing rates, and actual firing rates recorded via whole-cell patch clamp (Fig. 1E). This is expected, since the OGB-based calcium signal does not saturate for the range of action potential responses observed in our experiments. For the analysis in the rest of the manuscript, tuning functions are calculated from deconvolved calcium data (Vogelstein et al., 2010). Using the dF/F calcium data to measure tuning functions (Fig. 3A,C) does not change the results presented.

Three hundred and seventeen pyramidal neurons (∼47% of all visually responsive pyramidal cells, and 28% of all recorded cells) showed direction of motion selectivity (DSI, >0.5) in response to drifting gratings (Andermann et al., 2011; Rochefort et al., 2011). The median width of direction tuning was estimated at 28°, which is in line with previous data on the direction selectivity of V1 units from the mouse (Niell and Stryker, 2008; see Materials and Methods). Of those direction-selective cells, 235 (∼74%) were also responsive to drifting plaid stimuli (the 60° plaid, the 120° CA plaid, or both). We classified these neurons as CM-selective versus PM-selective, depending on how they responded to plaid stimuli, following the study by Smith et al. (2005). Figure 3, A and B, illustrates the tuning functions of four CM-selective example neurons, calculated from dF/F (Fig. 3A) and deconvolved calcium data (Fig. 3B). Neurons 1 and 2 showed CM-selective responses when tested with the 60° CA plaid, while neurons 3 and 4 showed CM-selective responses when tested with the 120° CA plaid. These neurons showed unimodal direction-of-motion tuning for grating stimuli (Fig. 3A,B, black curves) but bimodal tuning for plaids (60°, red; 120°, blue), with peaks offset by ∼30° for the 60° CA plaid (neurons 1 and 2) and by ∼60° for the 120° CA plaid (neurons 3 and 4). They are, therefore, selective for the direction of motion of component gratings, but not for the direction of motion of the resulting plaid texture (Figs. 3A,B, 4A,B, CM-selective neurons). Neurons 5–8 (Fig. 3C,D) had matching single peaks under either the plaid or the grating condition and were classified as PM-selective (Figs. 3C,D, 4A,B, PM-selective neurons). In addition, mouse V1 contains a substantial percentage of cells that are not responsive to gratings or show responses that are not tuned to gratings, which do generate directionally tuned responses for full-field plaids. Approximately 32% of visually responsive pyramidal cells (217 of 678) showed such properties. This finding stands in contrast with cats or primates, for which we can find no such reports in the literature describing V1. However, a small percentage of cells with similar properties (directionally tuned for the plaid patterns, but poorly responsive to gratings) were reported in marmoset MT (Solomon et al., 2011).

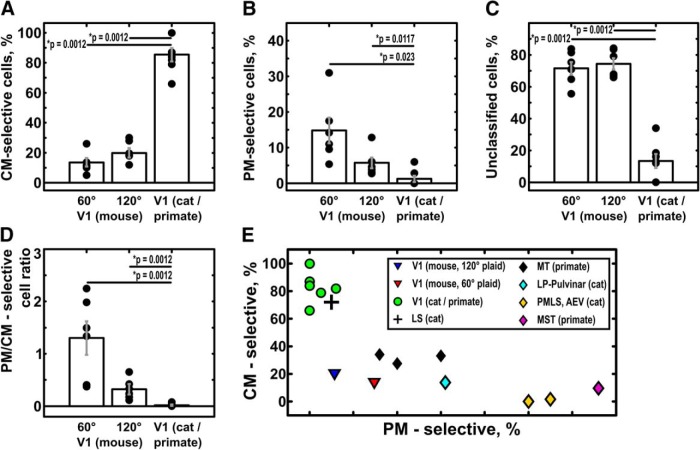

Pattern- and component-motion-selective responses in mouse V1 differ from cat and primate V1

To classify the responses of neurons as CM- or PM-selective, we computed the partial correlation coefficients of the plaid tuning function of each cell with the prediction for rp or rc (Fig. 2), taking into account the correlation between the two predictions (rpc; see Materials and Methods). Using the Fisher z-transform, we then converted the correlation measures (Rp, Rc) into z-scores (Zp, Zc) to assess significance (see Materials and Methods; Smith et al., 2005). Figure 4A shows population results obtained with the 60° CA plaid stimulus condition (Fig. 5A, corresponding z-score plot). The solid black line corresponds to confidence level p = 0.95. At this confidence level, 12.1 ± 2.5% of direction-selective L2/3 V1 cells generated PM-selective responses and 10.0 ± 2.0% generated CM-selective responses in the 60° CA plaid stimulus condition (mean ± SEM; error computed across animals, n = 6 animals). A lower percentage of PM-selective cells (4.4 ± 0.5%) was detected under the 120° CA plaid stimulus condition (Figs. 4B, 5B), while the percentage of CM-selective cells increased slightly (12.8 ± 2.6%). To compare our results with the literature, we also used the less selective criterion (p = 0.9) adopted by prior investigators (Gizzi et al., 1990; Smith et al., 2005). Using this criterion, 14.8 ± 3.6% of direction-of-motion-selective mouse V1 neurons were classified as PM-selective, and 13.6 ± 2.8% as CM-selective under the 60° CA plaid condition (mean ± SEM; n = 6 animals; Fig. 6A,B). For the 120° CA plaid, we found 5.7 ± 1.5% of PM-selective neurons and 19.9 ± 3.2% CM-selective neurons, respectively (mean ± SEM; n = 6 animals; Fig. 6A,B). These observations suggest that mouse V1 behaves differently from primate and cat V1, which seem to contain almost exclusively CM-selective neurons (Figs. 4C, 5C, 6A,E; Table 1). Under the same classification criterion, ∼84% of direction-of-motion-selective units recorded in cat and primate V1 under anesthesia are CM-selective (mean across seven studies using plaids with cross-angles ranging from 90° to 150°; Table 1; Fig. 6A). In contrast, the maximum average number of component neurons we obtained in the mouse V1 was ∼20% under the 120° cross-angle plaid (the maximum percentage of component cells obtained with the 120° plaid in an individual animal was 30%). The opposite trend is true for PM-selective units: essentially no PM-selective units are found in most cat and primate studies (∼1.3%, average over seven studies; a total of 3 PM-selective neurons were identified of 229 neurons in seven studies; Table 1; Fig. 6B,E), whereas mouse V1 on average has ∼6–15% PM-selective neurons, depending on the cross-angle of the plaid (Figs. 4A,B, 5A,B).

Figure 6.

Comparison of complex motion properties of mouse V1 and visual areas of primates and cats. WRS, Wilcoxon rank-sum test; 60°, mouse area V1, 60° plaid stimulation (n = 6 animals); 120°, mouse area V1, 120° plaid stimulation (n = 6 animals); V1 (cat/primate), primate or cat area V1 (n = 7 studies); LS, lateral suprasylvian area; PMLS, posteromedial lateral suprasylvian area; AEV, anterior ectosylvian visual area. Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM. Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to access the difference between groups. A, The percentage of component-motion-selective neurons in mouse V1 is considerably smaller than in primate and cat V1 [V1(p)] for both 60° and 120° plaids (p = 0.0012, WRS). B, The percentage of neurons showing pattern-motion selectivity in mouse V1 is significantly larger than in primate V1 for both 120° plaid (p = 0.0117, WRS) and 60° plaid (p = 0.0023, WRS). C, Mouse V1 shows a high percentage of cells that are direction selective but cannot be classified as either CM- or PM-selective. The content of unclassified cells in mouse V1 is significantly higher than in primate and cat V1 (120° plaid, p = 0.0012, WRS; 60° plaid, p = 0.0012, WRS). D, The ratio between PM-selective and CM-selective responses in mouse V1 significantly decreases with increasing cross-angle of the plaid (120° vs 60° plaid, p = 0.007, WRS) and is significantly different form near-zero values, found in primate V1 (primate V1 vs mouse V1, p = 0.0012, WRS; either cross-angle). E, The relationship between PM-selective and CM-selective responses in mouse V1 (60° plaid, red triangles; 120° plaid, blue triangles,), primate/cat V1 (green circles), thalamic nuclei (cyan rhomboids), and extrastriate visual areas of primates and cats (cross, cat area LS; yellow rhomboids, cat PMLS and AEV; black rhomboids, primate MT; violet rhomboids, primate MST). The ratio of PM- and CM-selective responses places mouse V1 in between primate/cat V1 and primate/cat extrastriate areas [apart from cat area LS (cross), which shows properties close to cat area V1].

Table 1.

Breakdown of pattern-motion-selective and component-motion-selective units in cat and primate visual areas under anesthesia

| Area, species | Pattern cells, % | Component cells, % | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| V1, cat | 0 | 87 | Gizzi et al. (1990) |

| V1, cat | 0 | 100 | Merabet et al. (1998) |

| V1, cat | 0 | 100 | Scannell et al. (1996) |

| V1 (layers 5, 6), monkey | 2.6 | 79 | Movshon and Newsome (1996) |

| V1, monkey | 6 | 82 | Khawaja et al. (2009) |

| V1 (layers 4C, 6), monkey | 0 | 66 | Guo et al. (2004) |

| V1 (cat and monkey) | 0 | 84 | Movshon et al. (1985) |

| Extrastriate | |||

| LS, cat | 5 | 72.5 | Gizzi et al. (1990) |

| PMLS, cat | 50 | 0 | Merabet et al. (1998) |

| AEV, cat | 55 | 1.6 | Scannell et al. (1996) |

| Pulvinar-LP, cat | 31 | 13.70 | Merabet et al. (1998) |

| MT, monkey | 20 | 27.4 | Movshon and Newsome (1996) |

| MT, monkey | 30 | 33 | Rodman and Albright (1989) |

| MT, monkey | 16 | 34 | Movshon et al. (1985) |

| MST, monkey | 66 | 9.6 | Khawaja et al. (2009) |

Generally, CM-selective units prevail in area V1 of anesthetized cats and monkeys. On average, 84% of directionally selective V1 cells are classified as CM-selective (66–100% depending on the study; see also Figs. 4C, 5C). Note that essentially no PM-selective cells are identified in V1 of anesthetized cats and monkeys (∼1.3% on average; none in most studies). To be exact, 1 of 38 V1 units was found to be PM-selective in one study (Movshon and Newsome, 1996) and 2 of 33 in another (Khawaja et al., 2009), and none were found in the rest of the studies (Movshon et al., 1985; Gizzi et al., 1990; Scannell et al., 1996; Merabet et al., 1998; Guo et al., 2004). Extrastriate areas and high-order thalamic nuclei contain a variable percentage of PM-selective units (5–55%) and CM-selective units (0–72.5%). LS, lateral suprasylvian area; PMLS, posteromedial lateral suprasylvian area; AEV, anterior ectosylvian area; LP, lateral posterior nucleus of thalamus.

The difference is made immediately evident if one considers the distribution of responses in the partial correlation space or z-score space (Figs. 4, 5). Note that there is a markedly different spread of neuronal responses elicited from mouse V1 (Figs. 4A,B, 5A,B) compared with the V1 of cats or primates (Figs. 4C, 5C). In fact, the distribution of partial correlations and associated z-scores is more similar between mouse V1 and cat/primate extrastriate cortex than cat/primate V1. Note that we mention this to stress the difference in area V1 complex motion processing across the species considered, and not to claim that motion processing in mouse V1 is equivalent to motion processing in cat/primate extrastriate cortex. In fact, the percentages of PM- and CM-selective units are lower in mouse V1 compared with cat/primate extrastriate areas.

One concern that arises, especially in the case of 60° cross-angle plaids, is whether PM versus CM classification can be performed accurately, given the width of the tuning functions. To ensure that our results are not artifactual, we used a bootstrap strategy and confirmed that we analyzed neurons for whom classification remained consistent across different subgroups of trials (see Materials and Methods). In any event, it is important to note that our basic conclusions hold true, even if we consider only results obtained with 120° cross-angle plaids (Fig. 6, summary).

Another possible confound arises because our data were collected using square-wave plaids and gratings versus the sine wave gratings used in the majority of prior studies. It has been argued before that components with different frequencies in these stimuli may alter cell characterization as CM- versus PM-selective. To ensure that this did not factor into the reported differences, we performed additional measurements for the dataset based on sine-wave gratings and 120° CA plaids (Figs. 4B, 5B, 60 direction-selective plaid-responsive from two animals are marked with gray dots), using the same procedures as for the square-wave data. In this dataset, ∼5% of cells showed PM-selectivity, and ∼13% were classified as CM-selective. Again, a major portion of the direction-selective cells (∼82%) could not be classified. The point spread of both z-scores and R values essentially corresponded to the respective spreads for the square-wave data (Figs. 4B, 5B). We conclude that using sine-wave versus square-wave stimuli does not alter our basic conclusions, and both classes of stimuli are similarly capable of eliciting CM- and PM-selective responses from mouse V1 neurons.

One important factor that can potentially affect the representation of CM- and PM-selective responses in visual cortex is recording depth (Movshon et al., 1985). In monkeys, the majority of the data on PM- and CM-selectivity of V1 neurons comes from deep layers of V1 (layer 4, layer 5 and 6 border, and layer 6; Movshon and Newsome, 1996; Guo et al., 2004). These studies in V1 found no apparent differences with respect to PM/CM selectivity in layers 4 through 6, finding that the overwhelming majority of the cells were CM-selective. The study by Solomon et al. (2011), collecting MT neurons throughout cortical thickness from layer 2 to 6, found no apparent functional difference between the layers in MT. Our OGB-1 data, on the other hand, come from layer 2/3, because imaging deeper layers with OGB-1 and other injectable calcium dyes in deeper layers required high laser power levels, which can result in photodamage. However, recently it became possible to also image deeper layers of the cortex using transgenic mice whose pyramidal neurons express the more efficient calcium-sensitive dye GCaMP6s (Madisen et al., 2015). We crossed Ai96 GCaMP6s reporter mice with mice expressing Cre-recombinase under nestin promoter (Tronche et al., 1999; Madisen et al., 2015). The offspring mice express fluorophore GCaMP6s in all cortical neurons. We used the resulting mice, expressing GCaMP6s in cortical neurons, to record data from layer 4 neurons and compare them to layer 2/3 neurons. We collected data from five layer 4 FOVs (four mice; depth, 360–460 μm below the pia; 190 direction-selective neurons) and four L2/3 FOVs (four mice; depth, 130–230 μm; 236 direction-selective neurons). Figure 7A shows all direction-selective L2/3 neurons recorded with GCaMP6s, and Figure 7B shows all recorded L4 direction-selective cells (black dots) plotted along the axes of component-motion and pattern-motion selectivity. The fraction of L4 pattern-motion-selective cells was commensurate with those in L2/3 (L4-GCaMP6s: PM, ∼8%; vs L2/3-GCaMP6s: PM, ∼10%; L2/3-OGB-1: PM, ∼6%). Layer 4 also has a smaller percentage of component-motion-selective cells than L2/3, whether measured with OGB-1 or GCaMP6s (L4-GCaMP6s: CM, ∼7%; vs L2/3-GCaMP6s: CM, ∼17%; L2/3-OGB-1: CM, ∼20%). In conclusion, L4, like L2/3, has the following: (1) a much lower proportion of component-motion-selective cells than would be expected in cat or monkey V1 (7% vs 84%); and (2) a higher proportion of pattern-motion-selective cells than would be expected in cat or monkey V1 (∼8% vs ∼1.3%; Table 1; Fig. 6).

Figure 7.

Component-motion and pattern-motion selectivity in layer 2/3 vs layer 4 of mouse V1. A, B, Scatter plot of component and pattern partial correlation coefficients calculated for each direction-of-motion-selective pyramidal neuron recorded in layer 2/3 of mouse V1 (A) vs layer 4 of mouse V1 (B), following the study by Smith et al. (2005). The x-axis plots the Rc value for each cell. The y-axis plots the Rp value for each cell. Dotted black line boundaries demarcate statistical significance levels calculated from the Fisher transform (see Materials and Methods; Smith et al., 2005) at p = 0.9. We use the p = 0.9 value here, since this is the value that has generally been used by previous investigators (Movshon and Newsome, 1996; Smith et al., 2005). Direction-tuning data were obtained using the fluorophore GCaMP6s and a stimulation protocol similar to the one used for OGB-1 data collection. A, Results for the layer 2/3 of V1, using 120° CA plaid (square-wave-gratings). The shape of the Rp–Rc distribution and the fraction of cells displaying pattern and component selectivity are essentially similar to the layer 2/3 data obtained using OGB-1 staining (Fig. 4B). Data were collected from four fields of view located at a depth of 130–230 μm. Of 236 cells that displayed direction-of-motion selectivity for the gratings, 23 cells were also pattern-motion selective (∼10%) and 41 cells were also component-motion selective (∼17%). B, Pattern-motion and component-motion selectivity in deep layers of mouse V1. Black filled dots, Results for layer 4 of mouse V1 obtained using the 120° CA plaid. Data were collected from five fields of view located at a depth of between 360 and 460 μm. Of 190 cells that displayed direction-of-motion selectivity for the gratings, 16 cells were also pattern-motion selective (∼8%), and 13 cells were component-motion selective (∼7%). Gray dots show results from 52 putative apical L5/6 dendrites recorded in L4 of mouse V1 (three FOVs, 400–460 μm deep) using the 120° CA plaid. Overall, the percentage of pattern-motion-selective responses detected in deeper layers (6–9%) is commensurate to that seen in L2/3 (9% in the GCaMP6s experiments; 6% in the OGB-1 experiments reported in the text).

To investigate the properties of cells in layers deeper than 4, we analyzed calcium signals arising from apical dendrites that traversed the plane of the image in the lower half of layer 4 (in the three deepest FOVs; depth, 400–460 μm; located at deep layer 4 or layer 4–layer 5 border) but did not connect to neuronal bodies located in the plane of imaging. These likely represent cross sections (2–4 μm in diameter) of apical dendrites arising in deeper layers (layers 5 and 6). Tuning properties of apical dendrites are thought to reflect closely those of the cell soma as they are dominated by back-propagating action potentials (Spruston, 2008). In total, we identified 52 such putative layer 5/6 apical dendrites that showed direction-of-motion selectivity for gratings. They are plotted as gray dots in Figure 7B and again mimic L2/3 data closely, as follows: ∼6% of putative L5/6 dendrites were PM-selective and ∼15% were CM-selective (Fig. 7B, gray dots). This is very different than aggregate reports in cat/monkey V1, which find ∼84% of CM-selective cells and ∼1.3% of PM-selective cells (Table 1). In summary, we show that the fraction of cells classified as PM- or CM-selective does not differ drastically between L2/3 and deeper cortical layers in mouse V1. In fact, plotting the cells along the axes of CM-selectivity and PM-selectivity (Fig. 7) yields very similar distributions in L2/3 (Fig. 7A), L4 (Fig. 7B, black dots), and putative L5/6 (Fig. 7B, gray dots). These distributions are broad and contain a small percentage of pattern-motion-selective cells (6–10%), with the majority of cells (∼73–85%) being unclassified.

Unclassified direction-selective responses in layer 2/3 of mouse V1

In the mouse, unlike in cats or primates, the vast majority of cells (∼74%) showing direction selectivity for drifting gratings generate responses for the plaid pattern that are not classifiable by the standard partial correlation analysis (Movshon and Newsome, 1996; Smith et al., 2005). However, these cells often have reasonable tuning functions when tested with the plaid stimuli. It is therefore interesting to examine the relationship between the peak of the tuning function elicited by plaids with that elicited by a drifting grating. First, we selected for analysis unclassified cells that have either (1) plaid-elicited tuning curves with a single peak (unidirection selective); or (2) plaid-elicited tuning curves that have two peaks in opposite directions (bidirection selective). We found that unidirection- and bidirection-selective cells constituted ∼60% of all unclassified cells (116 of 171 for the 60° CA plaid, and 96 of 167 for the 120° CA plaid). We next checked whether the preferred direction of the cell, when tested with a plaid, coincided with the preferred direction when tested using the grating or was offset from it (in 30° steps). Cells whose preferred direction when tested with plaids coincided with that elicited by gratings (pattern-motion aligned) constituted ∼21% of the unclassified unimodal cells for the 60° CA plaid data versus ∼6% for the 120° CA plaid data (see Fig. 10A, neuron 1, B, neuron 3). In contrast, ∼31% of the tuning curves of unclassified unimodal cells had peaks that coincided with the direction of drift of one of the two plaid components. Similar percentages of such component-sensitive cells were detected for the 60° and the 120° CA conditions (see Fig. 10A, neuron 2, B, neuron 4). Figure 10C shows the distribution of the offsets between the preferred direction of tuning curves elicited by plaids versus the tuning curves elicited by a single grating. While the distribution for the 60° plaid data was unimodal and centered at 0° (∼21% cells having no offset; i.e., pattern-motion aligned), the distribution for the 120° data had two peaks centering approximately at ±60° offsets (component-motion aligned), with only a small fraction (∼6%) of unclassified cells having no offset. As expected, the ratio of pattern-motion-aligned responses to component-motion-aligned responses was shifted in favor of component-motion sensitivity with increasing plaid cross-angle (see Fig. 10D). Overall, ∼52% of all unclassified cells show sensitivity for either pattern or component motion in the sense described above. These results suggest that even though unclassified cells have reduced selectivity for component versus pattern motion on a cell-by-cell basis, they may still contribute to motion processing and motion-based perceptual phenomena, like bistable perception, at the level of population responses.

Figure 10.

Unclassified direction-selective cells may contribute to population coding for pattern and component motion. A, B, Examples of plaid tuning found among direction-selective unclassified cells. A, Responses elicited with the 60° CA plaid (red) vs a drifting grating (black). B, Responses elicited with the 120° CA plaid (blue) vs a drifting grating (black). When tested with plaid stimuli, ∼60% of unclassified cells show unidirectional tuning or bidirectional tuning with opposite peaks. The peak of the tuning curves of the cells for plaids have variable offsets in relation to the peak of their tuning curves for gratings. This is the main reason that these cells failed to classify as clear component-motion or pattern-motion cells. We define neuron 2 and neuron 4 as being component-motion sensitive, since the peaks of the respective plaid tuning curves shift from the grating tuning curve peaks by half of the cross-angle of the plaid. Neuron 1 and neuron 3 are pattern-motion sensitive, since the dominant peaks for the plaid tuning curve are exactly aligned. C, Distribution of tuning curve peak offsets for the population of unimodal unclassified cells for 60° plaids (red, n = 116) and 120° plaids (blue, n = 96). The tuning curve peaks elicited by the drifting grating are set at 0° offset. While a considerable fraction of 60° plaid tuning curves share their peak with the grating tuning curve (∼21%), most tuning curves for 120° plaids deviate significantly: only 6% are exactly aligned with the peak of the tuning curve of the grating, while a significant proportion (∼31%) are offset by 60°. D, The ratio of pattern-motion-sensitive (PM-aligned) unclassified responses to component-motion-sensitive (CM-aligned) unclassified responses is significantly shifted in favor of component-motion-sensitive unclassified responses for the large-angle plaids (120° cross-angle; p = 0.0022, Wilcoxon rank-sum test). 60°, 0.87 ± 0.24 (n = 6 animals); 120°, 0.195 ± 0.07 (n = 6 animals). Error bars: mean ± SEM.

Origins of pattern-motion selectivity in mouse V1

Existing models of pattern-motion selectivity in MT (Rust et al., 2006) assume that pattern-motion-selective units pool the outputs of narrowly tuned component-motion-selective cells whose direction of motion preferences are spread over a wide range of directions. Indeed, it was shown that the main source of such component-motion-selective units is the deep layers of area V1 (Movshon and Newsome, 1996). Pattern-motion-selective cells in mouse area V1 could similarly obtain their properties from local V1 component-selective and unclassified direction-selective units. Alternatively, they could inherit their direction selectivity from subcortical targets, such as the pathway described by Cruz-Martin et al. (2014) originating in direction-selective retinal ganglion cells (Cruz-Martin et al., 2014) and supplying the direction information into the top layers of V1 through the orientation- and direction-selective units found in a mouse LGN shell (Piscopo et al., 2013; Marshel et al., 2011), bypassing layer 4. If the PM-selective cells in mouse V1 inherited their properties from local V1 direction-selective neurons, or LGN direction-selective neurons via a process analogous to the monkey MT pooling of V1 inputs as described in cascade models (Rust et al., 2006), one would expect them to show broader direction-tuning bandwidth for gratings compared with component and unclassified cells in V1, strong opponent motion inhibition, and cross-angle invariance of PM-selectivity (Rust et al., 2006; Solomon et al., 2011). Our experiments were not optimally designed to measure motion opponency. However, we were able to assess the width of direction tuning, the cross-angle invariance of PM-selectivity, and the difference in response strength between i) a single grating moving in the preferred direction, versus ii) the same grating moving in the preferred direction when it is presented as part of a plaid.

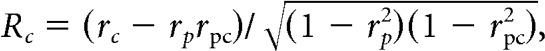

In our dataset, the tuning width of the PM-selective neurons was not significantly different from the tuning width of either unclassified or CM-selective cells. In fact, if anything, it was smaller: the median tuning bandwidth for PM-selective cells was ∼22°, compared with ∼30° for CM-selective cells and ∼28° for unclassified cells (data from 225 cells that were direction selective for the gratings and displayed responses also for the 120° cross-angle plaid; 11 PM-selective, 28 CM-selective, and 186 unclassified cells derived from six animals). PM-selective neurons in mouse V1 did show pronounced cross-component suppression: the responses of a cell to plaids containing a grating moving in its preferred direction were reduced compared to responses elicited by the grating presented alone. On average, the suppression was stronger for PM-selective versus CM-selective and unclassified cells [suppression index (R(plaid)/R(grating)): PM-selective cells, 0.13 (n = 11); other direction-selective cells, 0.28 (n = 214); p = 0.0082, Wilcoxon rank-sum test]. However, PM selectivity in mouse V1 is not cross-angle invariant, as PM-selective cell responses are generated for a narrower range of plaid cross-angles than would be typical for most units in monkey area MT. Once the cross-angle changes significantly, the responses become unclassified in the mouse (see Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Pattern-motion and component-motion selectivity in mouse V1 depends on the cross-angle of the plaid. Each graph plots the shift in the difference between pattern motion and component motion z-scores (i.e., Zp − Zc) for the 60° CA (narrow) plaid and the 120° CA (wide) plaid. If the cell lost tuning or became unresponsive as a result of change in the cross-angle of the plaid, (Zp − Zc) was set to 0. Areas of the plot that contain PM-selective (Zp − Zc > 1.28) or CM-selective responses (Zp − Zc < −1.28) are marked with PM and CM, respectively. Space between dotted red borders contains unclassified responses. A, Neurons that are pattern-motion selective for the 60° CA plaid; 63% of neurons that produced pattern-motion-selective responses for the 60° plaid (left column) had unclassified responses when tested with the 120° CA plaid. A minority (37%) of the neurons became CM-selective when tested with 120° CA plaid. B, Neurons that are PM-selective for the 120° CA plaid; 75% of neurons that produced pattern-motion-selective responses for the 120° plaid (left column) became unclassified when tested with the 60° CA plaid. Another 25% of these neurons showed CM-selective responses for the 60° CA plaid. C, Neurons that are component-motion selective for the 60° CA plaid; 55% of neurons that produced component-motion-selective responses for the 60° plaid (left column) became unclassified when tested with the 120° CA plaid. Another 26% of these neurons stayed CM-selective, while 19% showed PM-selective responses for the 120° CA plaid. D, Neurons that are component-motion selective for the 120° CA plaid; 55% of neurons that produced component-motion-selective responses for the 120° plaid (left column) became unclassified when tested with the 60° CA plaid. Another 35% of these neurons stayed CM-selective, while 10% showed PM-selective responses for the 60° CA plaid.

These observations together suggest that a cascade model like the one described by Rust et al. (2006), will need to be significantly modified from its current form in order to apply in mouse V1. Direction-selective cells in retina and LGN have considerably broader tuning than direction-selective cells in the V1, including PM-selective cells (Chen et al., 2009; Marshel et al., 2011), suggesting a different mechanism may be operating. The sensitivity of the PM responses to the cross-angle of the plaid suggests that PM-selectivity may rather rely on the geometry of the receptive field of the cell and whether local contrasts (“blobs”) exactly fit the on/off-subfields. This is akin to a process described by Tinsley et al. (2003) in a subset of unclassified marmoset V1 neurons that generated strong unidirectional responses to plaids. A change in cross-angle is thought to lead to the loss of size correspondence between local contrast blobs and the on/off-subfields, thereby engaging end-stopping mechanisms that suppress the response for certain directions (Tinsley et al., 2003). Overall, a more detailed study of receptive field properties and grating/plaid direction tuning functions is needed across various areas in the mouse visual system to pinpoint the precise mechanism of our observations.

Bistable perception of two-dimensional drifting patterns in mice and the role of V1