Abstract

The purpose of this study was to estimate the burden of osteoporotic fractures beyond the hospitalization period covering up to the first year after the fracture. This was a prospective, 12-month, observational study including patients aged ≥65 years hospitalized due to a first low-trauma hip fracture, in six Spanish regions. Health resource utilization (HRU), quality of life (QoL) and autonomy were collected and total costs calculated. Four hundred and eighty seven patients (mean ± SD age 83 ± 7 years, 77 % women) were included. Twenty-two percent of patients reported a prior non-hip low-trauma fracture, 16 % were receiving osteoporotic treatment at baseline, and 3 % had densitometry performed (1.8 % T-score ≤−2.5). Sixteen percent of patients died (women 14 %; men 25 %; p = 0.0011) during the first year. Mean hospital stay was 11.8 ± 7.9 days and 95.1 % of patients underwent surgery. Other relevant HRUs were: outpatient visits in 78 % of patients (mean 9.2 ± 9.7); walking aids, 58.7 %; rehabilitation facilities, 35.5 % (28.7 ± 41.2 sessions); and formal and informal home care, 22.2 % (49.6 ± 72.2 days) and 53.4 % (77.1 ± 101.0 h), respectively. Mean direct cost was €9690 (95 % confidence interval: 9184–10,197) in women and €9019 (8079–9958) in men. Main cost drivers were: first hospitalization episode (women €7067 [73 %]; men €7196 [80 %]); outpatient visits (€1323 [14 %]; €997 [11 %]); and home care (€905 [9 %]; €767 [9 %]). QoL and autonomy showed a marked decrease during hospitalization, not entirely recovered at 12 months (p < 0.05 vs. baseline for EQ-5D, Harris hip score and modified Barthel index). In a Spanish setting, osteoporotic hip fractures incur a high societal and economic cost, mainly due to the first hospitalization HRU, but also due to subsequent outpatient visits and home care.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00223-016-0193-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Osteoporosis, Hip fracture, Quality of life, Autonomy, Cost

Introduction

Osteoporosis is characterized by compromised bone strength predisposing to an increased risk of fracture [1]. In the year 2000, there were approximately 9.0 million osteoporotic fractures with the greatest number occurring in Europe (34.8 %) [2]. Osteoporosis and resulting fractures have significant consequences on human health, QoL and societal burden [2]. Hip fractures place a high burden for patients and healthcare systems due to the advanced age of affected patients, the need for complex surgeries and the high impact on patients’ mobility [3]. However, this burden is systematically underestimated since usually only the admission period is considered. Hip fractures are also associated with a high mortality both during hospitalization [3] and following discharge [4].

In Spain, the annual incidence of hip fractures in patients aged ≥65 years has been estimated at 36,000 (90.5 % of all hip fractures) [3], and it is continuously increasing due to an ageing population (increase of 18 % between 1997 and 2008 [5]). There is limited evidence quantifying the burden of hip fractures at the Spanish national and regional levels, taking into account the differences between regional Health Systems, with only three retrospective chart review studies [6–8] and one study extrapolating data from two clinical trials available [9]. Therefore, there is a need for an updated and reliable estimate of the cost of an osteoporotic hip fracture in Spain to help regions in their decision making.

The primary objective of this study was to estimate health resource utilization (HRU) and related costs associated with osteoporotic hip fractures over 12 months in patients of 65 years of age or older in Spain. The secondary objectives were: to describe patients’ characteristics, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), physical functioning and autonomy/dependency from others and the circumstances leading to the hip fracture.

Patients and Methods

The PROA (PRospective Observational study on burden of hip frActures in Spain) was a prospective, 12-month, observational study. Patients ≥65 years admitted to hospital due to a first osteoporotic hip fracture (defined as fracture due to a low impact or falling from a standing height or less or any mild or moderate trauma not resulting from a fall [10]) were included. The exclusion criteria were: hip fracture secondary to severe trauma (defined as a fall from a height higher than that of a stool, chair or first rung of a ladder, or severe trauma other than a fall), concurrent non-hip fracture, malignancy or primary bone disease, and participation in an interventional trial in the last 6 months. The protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee, and all patients gave written informed consent before enrolment. For patients who suffered from cognitive impairment, informed consent was given by a legal representative and patient-reported data were provided by the representative at each visit.

The study was conducted in six regions (Andalusia, Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia, Madrid and Valencia) including small (<200 beds), medium (200–500 beds) and large hospitals (>500 beds). Data were collected at baseline (first admission to hospital), hospital discharge and 4 and 12 months post-fracture. At baseline, the following variables were collected: demographic data, fracture risk factors, comorbidities (Charlson comorbidity index [11, 12]) and circumstances of the fall/event leading to the hip fracture. Fracture-associated HRUs were collected at all visits: inpatient care (length of hospital stay, imaging, type of surgery and/or prosthesis, treatment of complications); re-hospitalizations; ambulatory care (number and type of outpatient visits; physician or nurse), home visits (occupational therapist, physician and nurse) and/or telephone support; rehabilitation (number of physiotherapy sessions); walking aids; visits to emergency departments; and formal (social workers, nursing home stay, rehabilitation facility stay) and/or informal home care (relatives or paid worker). HRQoL (EuroQoL-5 dimensions [EQ-5D] questionnaire [13, 14]) and patient autonomy (modified Barthel index [15] and Harris hip score [16]) were also collected at all visits (retrospectively at baseline, in reference to the status prior to the fracture). HRUs at the time of death were not collected.

Statistical Analysis

The Spanish Healthcare System perspective has been applied, except for the informal home care resources. Unitary costs were obtained from the eSalud database (http://www.oblikue.com/bddcostes) and adjusted to 2012 values. Mean annual costs and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were calculated (using 1000 bootstrap samples). The cost of informal home care was estimated by applying the official national minimum wage in Spain. Data regarding home support (formal or informal) before the fracture were asked to the patient or proxy responder (e.g. caregiver or relative) at the beginning of the study. The cost associated with hip fracture was computed as the difference between that of care provided before and after the fracture, as utilized in previous studies [17].

Descriptive analyses were provided for each variable at all the study visits. Changes in continuous variables over time were analysed using paired T tests. Differences between subgroups of patients were tested using Student’s T tests, Mann–Whitney or Chi-squared tests, as applicable. Time to death was summarized using Kaplan–Meier methodology. Survival differences between men/women were evaluated using a univariate Cox regression model. Statistical analyses were performed with the SAS statistical software package (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Circumstances of the Fall Leading to the Hip Fracture

A total of 487 patients (77 % women) were included in 28 Spanish hospitals between 31 March 2011 and 29 June 2012. Of them, 357 (73.3 %) were followed up during 12 months. Most premature discontinuations (77/130, 59.2 %) were due to death.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of the study cohort. The mean (SD) age of patients with a first osteoporotic hip fracture was similar for both sexes: 83.2 (6.6) and 81.1 (7.0) for women and men, respectively. Around one-third of patients had at least one previous non-hip fracture, of which 59.7 % had been reported as low impact fractures. A total of 15.6 % of patients were receiving osteoporotic treatment at the time of the fracture occurrence, and only 3 % had undergone bone densitometry testing (1.8 % had BMD T-score ≤−2.5).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and osteoporosis risk profile of patients with a first osteoporotic hip fracture in Spain

| Women (N = 375) | Men (N = 112) | Total (N = 487) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 83.2 (6.6) | 83.1 (7.0) | 83.2 (6.7) |

| ≥75 years | 339 (90.4) | 100 (89.3) | 439 (90.1) |

| Sex, woman | – | – | 375 (77.0) |

| Type of centre | |||

| Small | 67 (17.9) | 26 (23.2) | 93 (19.1) |

| Medium | 101 (26.9) | 37 (33.0) | 138 (28.3) |

| Large | 207 (55.2) | 49 (43.8) | 256 (52.6) |

| Alcohol intake | 21 (5.6) | 26 (23.2) | 47 (9.6) |

| Active smoking | 7 (1.9) | 11 (9.8) | 18 (3.7) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| <18.5 | 8 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 8 (1.6) |

| 18.5–<25.0 | 159 (42.4) | 51 (45.5) | 210 (43.1) |

| 25.0–<30.0 | 112 (29.9) | 39 (34.8) | 151 (31.0) |

| ≥30.0 | 58 (15.5) | 12 (10.7) | 70 (14.4) |

| Missing | 38 (10.1) | 10 (8.9) | 48 (9.9) |

| Diagnosis of osteoporosis established by densitometry (T-score ≤−2.5) | 8 (2.1) | 1 (0.9) | 9 (1.8) |

| T-score not available | 362 (96.5) | 110 (98.2) | 472 (96.9) |

| Secondary osteoporosisa | 10 (2.7) | 4 (3.6) | 14 (2.9) |

| Prior non-hip fracture | 144 (38.4) | 37 (33.3) | 181 (37.2) |

| Prior non-hip fracture by low impact trauma | 88 (23.5) | 20 (17.9) | 108 (22.2) |

| Time since last fracture, months, median (Q1, Q3)b | 42.1 (18.7, 109.5) | 75.8 (28.2, 163.7) | 43.0 (20.4, 123.4) |

| Location of previous fracturesc | |||

| Wrist | 50 (13.3) | 10 (8.9) | 60 (12.3) |

| Shoulder | 24 (6.4) | 4 (3.6) | 28 (5.7) |

| Spine | 16 (4.3) | 7 (6.3) | 23 (4.7) |

| Upper arm | 17 (4.5) | 2 (1.8) | 19 (3.9) |

| Other | 67 (17.9) | 16 (14.3) | 87 (17.9) |

| Prior osteoporotic treatment | 70 (18.7) | 6 (5.4) | 76 (15.6) |

| Other risk factors for fracture | |||

| Parental hip fracture | 21 (5.6) | 9 (8.0) | 30 (6.2) |

| Use of glucocorticoids | 22 (5.9) | 5 (4.5) | 27 (5.5) |

| Diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis | 13 (3.5) | 1 (0.9) | 14 (2.9) |

| Main comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 75 (20.0) | 24 (21.4) | 99 (20.3) |

| Dementia | 44 (20.5) | 18 (16.1) | 95 (19.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 54 (14.4) | 28 (25.0) | 82 (16.8) |

| Congestive heart failure | 45 (12.0) | 13 (11.6) | 58 (11.9) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 48 (12.8) | 8 (7.1) | 56 (11.5) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 22 (5.9) | 26 (23.2) | 48 (9.9) |

| Myocardial infarction | 29 (7.7) | 19 (17.0) | 48 (9.9) |

| Any tumour | 13 (3.5) | 8 (7.1) | 21 (4.3) |

| Moderate or severe renal disease | 13 (3.5) | 8 (7.1) | 21 (4.3) |

| Charlson index, mean (SD)d | 1.8 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.7) | 1.9 (1.3) |

| Hip fracture result of a fall | 373 (99.5) | 110 (98.2) | 483 (99.2) |

| Living arrangements prior to the fall | |||

| Alone in own home | 82 (21.9) | 11 (9.8) | 93 (19.1) |

| Partner/family member sharing own home | 219 (58.4) | 79 (70.5) | 298 (61.2) |

| Nursing home | 40 (10.7) | 15 (13.4) | 55 (11.3) |

| Relatives home | 33 (8.8) | 7 (6.3) | 40 (8.2) |

| Patient alone at the time of a fall | 172 (45.9) | 38 (33.9) | 210 (43.1) |

| Where fall happened | |||

| Inside | 294 (78.4) | 84 (75.0) | 378 (77.6) |

| Outside | 79 (21.1) | 26 (23.2) | 105 (21.6) |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.8) | 4 (0.8) |

| If fall happened outside, weather conditions | |||

| Dry | 68 (18.1) | 21 (18.8) | 89 (18.3) |

| Wet | 10 (2.7) | 4 (3.6) | 14 (2.9) |

| Icy | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.4) |

| Season when the fall took place | |||

| Winter | 59 (15.7) | 19 (17.0) | 78 (16.0) |

| Spring | 74 (19.7) | 28 (25.0) | 102 (20.9) |

| Summer | 103 (27.5) | 28 (25.0) | 131 (26.9) |

| Autumn | 137 (36.6) | 35 (31.3) | 172 (35.3) |

| Missing | 2 (0.5) | 2 (1.7) | 4 (0.8) |

| Patient receiving medications that increase the risk of falls | 136 (36.3) | 35 (31.3) | 171 (35.1) |

Data are number of patients (percentage) except when otherwise indicated; a defined as conditions such as type I diabetes, osteogenesis imperfecta, untreated long-standing hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism or premature menopause, chronic malnutrition, or malabsorption and chronic liver disease; b calculated at enrolment in patients with a previous non-hip fracture; c subjects could have multiple previous fractures at different locations; subjects with more than one fracture in the same location were counted only once in that location; d valid N = 256/86/342 for women, men and overall, respectively; Q1 = 25th percentile; Q3 = 75th percentile; SD standard deviation

The majority of patients lived with a partner or family member sharing their own home (61.2 %), with 19.1 % living alone, 11.3 % living in a nursing home and 8.2 % living in a relative’s home. The circumstances of the fall leading to the hip fracture were similar between men and women. Most falls occurred inside, in the morning and in autumn or summer. Approximately one-third (35.1 %) of subjects were receiving medications that increase the risk of falls (Table 1).

During the follow-up, 18 (3.7 %) patients had at least one new fracture (total of 19 fractures, 95 % osteoporotic origin).

Health-Related Quality of Life and Patient Autonomy

The HRQoL results and changes in patient autonomy showed a statistically significant decrease during hospitalization and up to 12 months after (Table 2). Furthermore, patients living independent of caregivers or family members decreased after 12 months compared to baseline (36 vs. 77, respectively) (Online Resource 1).

Table 2.

Changes in health-related quality of life and patient autonomy during the 12-month follow-up

| Baseline (prior to the fracture) | Discharge | 4 months | 12 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D, health state index, mean (SD)a | 0.57 (0.39) | 0.04 (0.39)* | 0.47 (0.41)* | 0.53 (0.41)* |

| Valid N | 454 | 446 | 303 | 318 |

| Change from baseline, mean (95 % CI) | −0.54 (−0.58 to −0.50) | −0.11 (−0.16 to −0.06) | −0.06 (−0.11 to −0.01) | |

| Harris hip score, mean (SD)b | 74.9 (19.6) | 46.6 (14.6)* | 64.7 (17.9)* | 69.1 (18.9)* |

| Valid N | 353 | 341 | 223 | 244 |

| Change from baseline, mean (95 % CI) | −28.3 (−30.4 to −28.3) | −9.9 (−12.6 to −7.2) | −7.1 (−9.7 to −4.5) | |

| Modified Barthel index, mean (SD)c | 77.5 (26.9) | 40.4 (24.3)* | 66.4 (31.4)* | 70.4 (31.1)* |

| Valid N | 441 | 433 | 287 | 306 |

| Change from baseline, mean (95 % CI) | −37.3 (−39.5 to −35.1) | −12.2 (−14.9 to −9.5) | −9.8 (−12.5 to −7.1) |

aThe health state index score ranges between −0.594 and 1.0. A higher score indicates a more preferred health status, b Harris hip score ranges between 0 and 100. A higher score indicates better function, c the modified Barthel index ranges between 0 and 100. A higher score indicates better function

* p < 0.05 versus baseline

Health Resource Utilization

HRU was high, both during the first hospitalization and at 12-month follow-up. The results were similar across genders, except for re-hospitalizations which were more frequent among women versus men (6.4 vs. 3.6 %).

The 95.1 % of patients underwent surgery, mainly intramedullary nail osteosynthesis in women and partial prosthesis in men. Mean length of hospital stay during first hospitalization was 11.8 ± 7.9 days (Tables 3, 4).

Table 3.

Health resource utilization

| Women (N = 375) | Men (N = 112) | Total (N = 487) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First hospitalization | |||

| Hospital stay, days, mean (SD) | 11.8 (7.9) | 11.9 (8.1) | 11.8 (7.9) |

| Median (min–max) | 10.0 (1–69) | 10.0 (2–54) | 10.0 (1–69) |

| Geriatric ward, % | 0.5 | 1.7 | 0.8 |

| Days, mean (SD) | 5.0 (1.4) | 12.0 (2.8) | 8.5 (4.4) |

| Intensive care, % | 26.7 | 22.3 | 25.7 |

| Days, mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.5 (2.0) | 1.1 (0.9) |

| Orthopaedic ward, % | 99.2 | 98.2 | 99.0 |

| Days, mean (SD) | 11.4 (7.7) | 11.4 (8.0) | 11.4 (7.8) |

| Other wards, % | 2.1 | 0.8 | 3.7 |

| Days, mean (SD) | 2.9 (5.3) | 1.7 (1.6) | 2.2 (3.6) |

| Surgical intervention, % | 95.7 | 92.9 | 95.1 |

| Intramedullary nail osteosynthesis | 45.3 | 31.3 | 42.1 |

| Sliding screw osteosynthesis | 17.6 | 17.9 | 17.7 |

| Partial prosthesis | 28.5 | 36.6 | 30.4 |

| Total prosthesis | 4.8 | 8.0 | 5.5 |

| Imaging | 96.8 | 99.1 | 97.3 |

| CT, % | 5.9 | 6.2 | 6.0 |

| Num. times used, mean (SD) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.0 (0) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| Ultrasound, % | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.3 |

| Num. times used, mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.5) |

| X-ray, % | 96.8 | 99.1 | 97.3 |

| Num. times used, mean (SD) | 4.0 (1.8) | 4.2 (1.7) | 4.0 (1.8) |

| Other proceduresa, % | 0.5 | 58.9 | 49.9 |

| Num. times used, mean (SD) | 5.8 (3.5) | 6.4 (5.0) | 5.9 (3.9) |

| Emergency room visit prior to hospitalization, % | 86.9 | 84.8 | 86.4 |

| 12-month follow-up | |||

| Re-hospitalizations, % | 6.4 | 3.6 | 5.7 |

| Hospital stay, days, mean (SD) | 16.2 (13.9) | 5.8 (4.5) | 14.7 (13.4) |

| Median (min–max) | 12.5 (2–56) | 4.5 (2–12) | 10.5 (2–56) |

| Imaging, % | 5.9 | 3.6 | 5.3 |

| Surgical intervention, % | 0.8 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Intramedullary nail osteosynthesis | 0.5 | 0 | 0.4 |

| Partial prosthesis | 0.3 | 0 | 0.2 |

| Other proceduresa, % | 4.3 | 3.6 | 4.1 |

| Ambulatory care | |||

| Outpatient visits, % | 81.3 | 67.0 | 78.0 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 9.1 (9.5) | 9.4 (10.9) | 9.2 (9.7) |

| Median (min–max) | 6.0 (1–75) | 6 (1–58) | 6 (1–75) |

| Nurse at health centre visits, % | 31.7 | 31.2 | 31.6 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 3.2 (4.9) | 1.9 (1.4) | 2.9 (4.4) |

| Nurse’s home visits, % | 39.5 | 33.0 | 38.0 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 5.8 (7.1) | 7.1 (8.5) | 6.0 (7.4) |

| Physician at health centre visits, % | 38.7 | 38.4 | 38.6 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 3.0 (2.4) | 2.8 (2.3) | 3.0 (2.4) |

| Specialist, % | 61.9 | 57.1 | 60.8 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.5) | 2.8 (3.0) | 3.0 (2.6) |

| Physician’s home visits, % | 29.1 | 15.2 | 25.9 |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 3.4 (3.8) | 4.6 (4.3) | 3.6 (3.9) |

| Rehabilitation facility, % | 36.3 | 33.0 | 35.5 |

| Number of sessions, mean (SD) | 28.5 (43.2) | 29.6 (33.5) | 28.7 (41.2) |

| Median (min–max) | 16 (1–320) | 14 (1–128) | 15 (1–320) |

| Health centre, % | 14.7 | 11.6 | 14.0 |

| Number of sessions, mean (SD) | 27.4 (25.3) | 36.8 (38.5) | 29.2 (28.2) |

| Home, % | 24.5 | 25.9 | 24.8 |

| Number of sessions, mean (SD) | 25.7 (41.1) | 21.3 (23.9) | 24.7 (37.6) |

| Imaging, % | 4.0 | 1.8 | 3.5 |

| Num. times used, mean (SD) | 6.5 (4.7) | 6.0 (5.7) | 6.4 (4.6) |

| Other proceduresa, % | 2.4 | 1.8 | 2.3 |

| Num. times used, mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.7) | 2.5 (2.1) | 2.1 (1.6) |

| Ambulance use, % | 53.3 | 37.5 | 49.7 |

| Num. times used, mean (SD) | 5.0 (10.6) | 4.0 (4.4) | 4.8 (9.8) |

| Visits to emergency room, % | 16.0 | 14.3 | 15.6 |

| Num. times used, mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.2) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.8 (2.0) |

| Walking aids, % | 60.3 | 53.6 | 58.7 |

| Walker | 49.9 | 44.6 | 48.7 |

| Wheelchair | 16.5 | 14.3 | 16.0 |

| Home care | |||

| Formal, % | 23.7 | 17.0 | 22.2 |

| Days, mean (SD) | 47.1 (66.7) | 61.6 (95.1) | 49.6 (72.2) |

| Median (min–max) | 26.5 (1–411) | 47.0 (1–618) | 25.1 (1–411) |

| Care from social workers, % | 4.5 | 5.4 | 4.7 |

| Days, mean (SD) | 6.6 (8.2) | 5.8 (2.8) | 6.4 (7.2) |

| Nursing home, % | 8.8 | 4.5 | 7.8 |

| Days, mean (SD) | 56.7 (63.5) | 110.0 (96.9) | 63.7 (69.6) |

| Rehabilitation facility, % | 15.5 | 10.7 | 14.4 |

| Days, mean (SD) | 38.1 (38.0) | 48.7 (45.3) | 39.9 (39.2) |

| Informal, % | 56.5 | 42.9 | 53.4 |

| Hours, mean (SD) | 78.0 (103.7) | 73.1 (89.3) | 77.1 (101.0) |

| Median (min–max) | 35 (1–672) | 38 (2–336) | 35 (1–672) |

| Cared by relatives, % | 49.3 | 39.3 | 47.0 |

| Hours, mean (SD) | 64.7 (81.7) | 61.8 (79.4) | 64.1 (81.1) |

| Paid worker, % | 24.5 | 16.1 | 22.6 |

| Hours, mean (SD) | 49.6 (69.9) | 44.0 (67.3) | 48.7 (69.2) |

Mean (SD) number of each HRU calculated among those patients reporting 1 or more

aMainly blood tests; CT computed tomography, SD standard deviation

Table 4.

Direct medical costs during the first year after a first osteoporotic hip fracture

| Mean € (95 % CI) | Women (N = 375) | Men (N = 112) |

|---|---|---|

| Total direct cost | 9690 (9184, 10,197) | 9019 (8079, 9958) |

| First hospitalization | ||

| First hospitalization | 7067 (6733, 7401) | 7196 (6522, 7870) |

| Hospital stay | 4796 (4469, 5122) | 4856 (4240, 5472) |

| Geriatric ward | 11 (0, 26) | 88 (0, 211) |

| Intensive care | 154 (127, 181) | 184 (66, 301) |

| Orthopaedic ward | 4631 (4311, 4950) | 4584 (3964, 5205) |

| Surgical intervention | 2064 (1997, 2131) | 2128 (1969, 2288) |

| Intramedullary nail osteosynthesis | 795 (706, 884) | 545 (393, 697) |

| Sliding screw osteosynthesis | 401 (312, 490) | 401 (239, 562) |

| Partial prosthesis | 691 (580, 803) | 887 (667, 1106) |

| Total prosthesis | 177 (97, 257) | 296 (108, 484) |

| Imaging | 89 (83, 94) | 96 (87, 106) |

| Computed tomography | 6 (3, 8) | 5 (1, 9) |

| Ultrasound | 4 (2, 5) | 5 (0, 10) |

| X-ray | 80 (76, 84) | 87 (80, 94) |

| Emergency room visit prior to hosp. | 118 (114, 123) | 115 (106, 125) |

| 12-month follow-up | ||

| Re-hospitalizationb | 395 (173, 617) | 59 (0, 120) |

| Ambulatory care | 1323 (1119, 1528) | 997 (753, 1241) |

| Outpatient visits | 329 (291, 367) | 281 (204, 359) |

| Nurse at health centre visits | 16 (11, 21) | 10 (6, 13) |

| Nurse’s home visits | 73 (56, 91) | 75 (40, 110) |

| Physician at health centre visits | 56 (46, 66) | 50 (33, 68) |

| Specialist | 122 (106, 138) | 104 (72, 135) |

| Physician’s home visits | 62 (46, 78) | 43 (16, 70) |

| Rehabilitation facility | 284 (191, 376) | 258 (142, 373) |

| Health centre | 48 (32, 65) | 52 (12, 91) |

| Home | 235 (148, 323) | 206 (100, 313) |

| Imaging | 6 (2, 10) | 3 (0, 8) |

| Ambulance use | 486 (336, 635) | 269 (157, 382) |

| Visits to emergency room | 42 (26, 57) | 29 (14, 44) |

| Walking aids | 177 (148, 207) | 157 (104, 210) |

| Walker | 55 (49, 62) | 49 (37, 60) |

| Wheelchair | 122 (92, 152) | 109 (55, 162) |

| Home care, mean use | 905 (690, 1121) | 767 (285, 1250) |

| Formal | 603 (397, 810) | 563 (116, 1009) |

| Care from social workers | 18 (5, 31) | 18 (3, 35) |

| Nursing home | 258 (129, 387) | 254 (−30, 538) |

| Rehabilitation facility | 327 (213, 441) | 290 (74, 506) |

| Informal | 302 (236, 368) | 205 (114, 296) |

| Cared by relatives | 162 (128, 196) | 123 (68, 178) |

| Paid worker | 140 (93, 188) | 81 (15, 148) |

CI confidence interval, Hosp hospitalization

There was a large number of outpatient visits (median: 6.0, range: 1–75), use of rehabilitation facilities (median: 15 sessions, range: 1–320), walking aids (58.7 % of patients) and home care (22.2 % of patients with formal care [median of 25 days] and 53.4 % with informal care [median of 35 h]) (Table 3). Seventy-seven patients (15.8 %) required both formal and informal home care.

Direct Medical Costs

Mean total cost during the first year was €9690 (95 % CI: 9184–10,197) in women and €9019 (8079–9958) in men, with no significant differences between genders except for the cost of re-hospitalizations (Table 4).

The main cost determinant was first hospitalization (€7067 and €7196 in women and men, respectively), followed by ambulatory care and home care (Table 4).

Subgroup Analyses by Size of Centre

When HRU was analysed by size of centre, large centres showed longer hospital stays (mean of 13.8 days versus 10.2 and 9.0 in small and medium centres, respectively). However, after discharge, patients treated at small centres had more outpatient visits (mean of 10.0 [in all patients] versus 6.3 and 6.5 in medium and large centres), rehabilitation sessions (mean of 17.1 vs. 10.7 and 7.4) and formal home care (mean of 16.6 days vs. 10.5 and 9.3), but less informal care (mean of 29.1 h vs. 48.6 and 41.5 in medium and large centres).

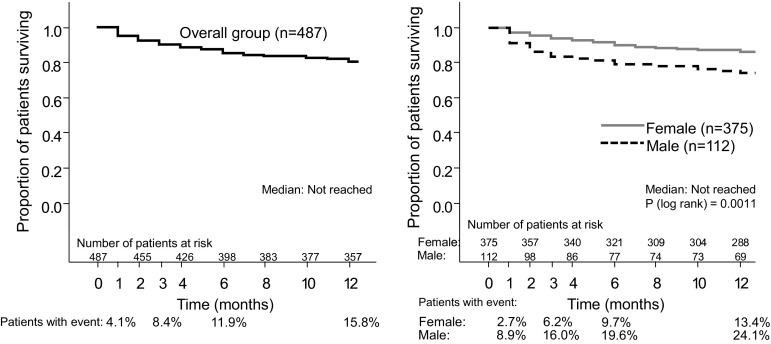

Mortality

During the 12-month follow-up, 15.8 % of patients died, 53 % of them within the first 3 months (Fig. 1). Mortality was significantly higher in men than in women (24.1 vs. 13.4 %, respectively, p = 0.0011).

Fig. 1.

Mortality in the overall group and by gender in the first year after a first osteoporotic hip fracture

Discussion

The PROA constitutes the first large, multicentre, prospective study specifically designed to provide estimates on the cost of osteoporotic hip fractures in Spain. Overall, the socio-demographic characteristics of our cohort were comparable to those from similar studies conducted in Belgium [18], Sweden [19] or the UK [20]. Nevertheless, there were some notable differences between this and other national studies. The mean age of this cohort was similar for both sexes and higher than that reported previously, most likely due to the comparatively higher proportion of patients aged 75 years old or above [3, 21, 22]. Furthermore, while the proportion of patients sharing their own home/living alone was similar to that of the Spanish population, the proportion of patients living in a nursing home was greater in this cohort compared to national averages [23]. Lastly, the prevalence of prior vertebral fractures was extremely low (4.7 %) compared to the estimated 20 % in the Spanish population of similar age, most likely due to the fact that in this study only fractures that were documented in the patient’s medical file were collected as opposed to the acquisition of X-rays of the thoracic and lumbar spine using the Genant method [24, 25]. That being said, the similar prevalence of vertebral fractures previously registered in the patient’s file (1.2–4.3 %) reflects the underdiagnosis of these fractures in the daily practice [24].

Of note, almost all first osteoporotic hip fractures occurred in individuals at high risk of fracture, although only a low percentage were previously diagnosed and treated for osteoporosis. The treatment gap (patients eligible for treatment not receiving any drug) for osteoporosis in 2010 was estimated between 57 % (women) and 59 % (men) in the European Union [1]. In Spain, this gap was 25 and 20 %, but in our cohort it could be >30 %, according to the high prevalence of prior osteoporotic fractures and an important underuse of osteoporotic treatments in the recent years [26].

Similarly to previous studies [18, 19, 27], HRU during hospitalization was high, mainly related to a long hospital stay and to the need for surgery. The mean hospital stay (12 days) was similar than that reported in local studies [7] and in a previous analysis of Minimum Basic Data Set between 1997 and 2008 (13 days) [28], but much lower than the 23-day length reported in 1989 [8]. Health resource utilization in the first year following hospital discharge was similar to the observed in Sweden or Belgium [18, 19, 27]. The proportion of patients with re-hospitalization related to the hip fracture was very low in comparison with previous studies that collected all type of hospitalizations (17–30 %) [29, 30].

The cost obtained for the first hospitalization (~€7000) was consistent with the disease-related groups applicable to hip fracture in Spain (210, 211, 236, 558 and 818, cost: €2684-€14,878) [28]. This cost increased by 70 % between 1997 and 2008 in Spain (€4909 to €8365) [8, 28], probably related to the increase in mean age (2 years) and comorbidities of the patients, and the increase in the number of surgical interventions (86 % in 1997) [28].

The total cost in the first year after the first fracture (~€9000) is higher than that reported in Spain after a non-fatal stroke (€4638) but lower than after a myocardial infarction (€19,277) [31]. Our study suggests that, if only the first hospitalization is considered, one-fourth of the total annual cost of a hip fracture might be underestimated.

Compared to other European countries, the cost seems to be approximately a 25 % lower (€13,470 in Belgium; €14,221 in Sweden). In a UK cohort, the cost was slightly lower (€7536) [20], but in that study the costs associated with rehabilitation services and home care were not taken into account.

Mortality was high, especially in males (24.1 %). In both genders, mortality rates were almost three times higher compared to the annual mortality rate of Spanish general population of a similar age (7.4 and 4.5 %, respectively, in males and females of 80–84 years old) [32].

Prior to the fracture, the HRQoL was similar to that reported in Spanish population aged ≥85 [33], but it showed a marked worsening during the hospital stay and was not entirely resolved after 12 months, highlighting the long-term burden of the hip fracture.

Our study has some limitations. The similarity in age between sexes combined with the high proportion of patients aged 75 years old or above may limit the generalizability of these results to all patients with osteoporotic hip fractures in Spain aged ≥65 years old. The total cost may have been underestimated due to the inability of the study to collect the HRU at the time of death, inherent to the nature of observational design. Patient-reported HRU after hospital discharge, such as visits to the general practitioner, emergency room visits or re-hospitalizations, may have been underestimated due to the inability of the patient to recall information, leading to potential misclassification.

Strengths of our study include the large sample size and the geographically distributed recruitment, which ensures that it represents the regional diversity of Spain. Also, the prospective follow-up allowed a more comprehensive data collection on both the economic and humanistic burden of the condition not routinely included in patients’ medical records.

In conclusion, in a Spanish setting, osteoporotic hip fractures incur a high societal and economic cost, mainly due to the high HRU during the first hospitalization, but also due to subsequent outpatient visits and home care. Hip fractures were also associated with a high mortality of approximately one in six patients during the first year. The high prevalence of known risk factors and the low number of patients receiving prophylactic treatment highlight the undertreatment of this population, typically women older than 75 years with prior fractures, several comorbidities such as diabetes or dementia, and receiving medications that increase the risk of falls. By comparison, men in this study cohort not only received less osteoporosis follow-up prior to the hip fracture, but also exhibited a greater frequency of risk factors such as smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. Together, these results reflect the need for improving the diagnostic and therapeutic management of osteoporosis in Spain.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Writing assistance was supported by Amgen and provided by Neus Valveny, PhD, from TFS Develop. The authors wish to thank Jorge Arellano (MSc, Amgen Inc) for his contribution to the study design, and all the Investigators of the PROA Study (in alphabetical order by hospital name): Complejo Hospitalario Ourense: Dr. Antonio Fernández-Cebrián; Complejo Hospitalario Pontevedra—Hospital Montecelo: Dr. Eduardo Vaquero-Cervino; Complejo Hospitalario Santiago—Hospital Médico Quirúrgico de Conxo: Dr. José Ramón Caeiro; Fundación Jiménez Díaz: Dr. Emilio Calvo; Hospital Alto Deba: Dr. Íñigo Etxebarría-Foronda; Hospital Regional Universitario Carlos Haya: Dr. Manuel Bravo-Bardají; Hospital Comarcal Sant Bernabe de Berga, Dr. Pere Mir-Batlle; Hospital da Costa: Dr. Luís-Ángel Montero-Furelos; Hospital Universitario Donostia: Dr. Gaspar de la Herran-Núñez; Hospital Universitario de la Ribera: Dr. Francisco José Tarazona-Santabalbina; Hospital Txagorritxu: Dr. Rubén Goñi-Robledo, Dra. Naiara Gorostiaga-Perez; Hospital de Vinarós: Dr. Miguel-Angel Valero-Queralt; Hospital El Escorial: Dr. Guillermo Sánchez-Inchausti; Hospital General Universitario de Alicante: Dra. Isabel Serralta-Davia; Hospital General de Vic: Dr. Joaquín Rodríguez-Miralles; Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol: Dr. Xavier Granero-Xiberta; Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor: Dra. Fátima Brañas-Baztán; Hospital Lluís Alcanyís: Dr. Vicente Climent-Peris; Hospital Municipal de Badalona: Dra. Núria Galofré-Álvaro, Dra. Ana Serrado-Iglesias, Dra. Josefa Torres-Martínez; Hospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa: Dr. Agustí Bartra-Ylla; Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal: Dra. Susana Alonso-Güemes; Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía: Dr. Pedro Carpintero-Benítez; Hospital San Agustín de Linares: Dr. Alberto Delgado-Martínez; Hospital Universitario de Getafe: Dr. Leocadio Rodríguez-Mañas, Dra. Cristina Alonso-Bouzón, Dra. Olga Laosa-Zafra; Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón: Dr. Jorge Montejo-Sancho; Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebrón: Dr. Vicente Molero-García; Hospital Valle de los Pedroches: Dr. Manuel Mesa-Ramos; Hospital Virgen de la Macarena: Dr. Luís-Javier Roca-Ruíz.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Amgen, S.A.

Authors’ Contribution

Jose Ramón Caeiro, Manuel Mesa-Ramos, Francesc Sorio, Sonia Gatell and Laura Canals designed the study. Jose Ramón Caeiro, Agustí Bartra, Manuel Mesa-Ramos, Íñigo Etxebarría, Jorge Montejo, Pedro Carpintero and Andrea Farré contributed to the experimental work. All authors were responsible for analysis of the data. All authors revised the paper critically for intellectual content and approved the final version. All authors agree to be accountable for the work and to ensure that any questions relating to the accuracy and integrity of the paper are investigated and properly resolved.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

F Sorio, S Gatell, A Farre and L Canals are employees of Amgen. JR Caeiro has participated as principal investigator and/or collaborator in clinical trials sponsored by Lilly and Amgen and has been speaker at scientific events of Lilly, Merck, Pfizer and Servier. M. Mesa has been principal investigator in a clinical trial sponsored by Nycomed and speaker at scientific events of Procter & Gamble, Lilly and MSD. P Carpintero has participated as principal investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Amgen, MSD, Lilly and Nycomed, has been speaker at scientific events of Amgen, MSD, Lilly and Nycomed and has been advisor of MSD, Lilly y Bayer. A Bartra, I Etxebarría and J Montejo declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Jose Ramón Caeiro, Phone: +34-609458500, Email: jrcaeiro@telefonica.net.

on behalf of the PROA investigators:

Antonio Fernández-Cebrián, Eduardo Vaquero-Cervino, José Ramón Caeiro, Emilio Calvo, Íñigo Etxebarría-Foronda, Manuel Bravo-Bardají, Pere Mir-Batlle, Luís-Ángel Montero-Furelos, Gaspar de la Herran-Núñez, Francisco José Tarazona-Santabalbina, Rubén Goñi-Robledo, Naiara Gorostiaga-Perez, Miguel-Angel Valero-Queralt, Guillermo Sánchez-Inchausti, Isabel Serralta-Davia, Joaquín Rodríguez-Miralles, Xavier Granero-Xiberta, Fátima Brañas-Baztán, Vicente Climent-Peris, Núria Galofré-Álvaro, Ana Serrado-Iglesias, Josefa Torres-Martínez, Agustí Bartra-Ylla, Susana Alonso-Güemes, Pedro Carpintero-Benítez, Alberto Delgado-Martínez, Leocadio Rodríguez-Mañas, Cristina Alonso-Bouzón, Olga Laosa-Zafra, Jorge Montejo-Sancho, Vicente Molero-García, Manuel Mesa-Ramos, and Luís-Javier Roca-Ruíz

References

- 1.Hernlund E, Svedbom A, Ivergård M, et al. Osteoporosis in the European Union: medical management, epidemiology and economic burden. A report prepared in collaboration with the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industry Associations (EFPIA) Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:136. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1726–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez-Nebreda ML, Jiménez AB, Rodríguez P, Serra JA. Epidemiology of hip fracture in the elderly in Spain. Bone. 2008;42:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manzarbeitia J. Las fracturas de cadera suponen un coste de 25.000 millones de euros al año en la UE. Rev Esp Econ Salud. 2005;4:216–217. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad—Portal Estadístico del SNS—Sistema de Información Sanitaria: Portal Estadístico del SNS—Registro de Altas de los Hospitales del Sistema Nacional de Salud. CMBD. http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/cmbdhome.htm. Accessed 8 Jul 2015

- 6.Calvo-Crespo E, Sicras-Mainar A, Larrainzar-Garijo R (2010) Costes relacionados con las fracturas osteoporóticas en España. Jornadas Economía de la Salud P017

- 7.Etxebarria-Foronda I, Mar J, Arrospide A, Ruiz de Eguino J. Cost and mortality associated to the surgical delay of patients with a hip fracture. Spain. Rev Esp Salud Pública. 2013;87:639–649. doi: 10.4321/S1135-57272013000600008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Díez Pérez A, Puig Manresa J, Martínez Izquierdo MT, et al. Estimate of the costs of osteoporotic fractures of the femur in Spain. Med Clin. 1989;92:721–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouee S, Lafuma A, Fagnani F, et al. Estimation of direct unit costs associated with non-vertebral osteoporotic fractures in five European countries. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:1063–1072. doi: 10.1007/s00296-006-0180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackey DC, Lui L, Cawthon PM, et al. High-trauma fractures and low bone mineral density in older women and men. JAMA. 2007;298:2381–2388. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.20.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.EuroQol Group EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy Amst Neth. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badia X, Roset M, Montserrat S, et al. The Spanish version of EuroQol: a description and its applications. European Quality of Life scale. Med Clín. 1999;112(Suppl 1):79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah S, Vanclay F, Cooper B. Improving the sensitivity of the Barthel Index for stroke rehabilitation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42:703–709. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Söderman P, Malchau H (2001) Is the Harris hip score system useful to study the outcome of total hip replacement? Clin Orthop Relat Res (384):189–197 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Zethraeus N, Strömberg L, Jönsson B, et al. The cost of a hip fracture. Estimates for 1,709 patients in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68:13–17. doi: 10.3109/17453679709003968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haentjens P, Autier P, Barette M, et al. The economic cost of hip fractures among elderly women. A one-year, prospective, observational cohort study with matched-pair analysis. Belgian Hip Fracture Study Group. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:493–500. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200104000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borgström F, Zethraeus N, Johnell O, et al. Costs and quality of life associated with osteoporosis-related fractures in Sweden. Osteoporos Int. 2005;17:637–650. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gutiérrez L, Roskell N, Castellsague J, et al. Study of the incremental cost and clinical burden of hip fractures in postmenopausal women in the United Kingdom. J Med Econ. 2011;14:99–107. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.547967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrera A, Martínez AA, Ferrandez L, et al. Epidemiology of osteoporotic hip fractures in Spain. Int Orthop. 2006;30:11–14. doi: 10.1007/s00264-005-0026-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azagra R, López-Expósito F, Martin-Sánchez JC, et al. Incidence of hip fracture in Spain (1997–2010) Med Clín. 2015;145:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.medcli.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social, Instituto de Mayores y Servicios Sociales (IMSERSO) (2010) Encuesta sobre personas mayores 2010

- 24.Sanfélix-Genovés J, Reig-Molla B, Sanfélix-Gimeno G, et al. The population-based prevalence of osteoporotic vertebral fracture and densitometric osteoporosis in postmenopausal women over 50 in Valencia, Spain (the FRAVO study) Bone. 2010;47:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC. Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res Off J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:1137–1148. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanfélix-Gimeno G, Hurtado I, Sanfélix-Genovés J, et al. Overuse and underuse of antiosteoporotic treatments according to highly influential osteoporosis guidelines: a population-based cross-sectional study in Spain. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0135475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanis JA, Borgström F, Compston J, et al. SCOPE: a scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:1–63. doi: 10.1007/s11657-013-0144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Instituto de Información Sanitaria. Estadísticas Comentadas: La atención a la fractura de cadera en los hospitales del SNS. Madrid (Ministerio de Sanidad y Política Social; 2010). http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/docs/Estadisticas_comentadas_01.pdf. Accessed 28 Jul 2015

- 29.Giusti A, Barone A, Razzano M, et al. Predictors of hospital readmission in a cohort of 236 elderly discharged after surgical repair of hip fracture: one-year follow-up. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2013;20:253–259. doi: 10.1007/BF03324779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ottenbacher KJ, Smith PM, Illig SB, et al. Hospital readmission of persons with hip fracture following medical rehabilitation. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;36:15–22. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4943(02)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ray JA, Valentine WJ, Secnik K, et al. Review of the cost of diabetes complications in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy and Spain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1617–1629. doi: 10.1185/030079905X65349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ministerio de Sanidad, servicios sociales e igualdad (2015) Patrones de mortalidad en España, 2012. http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/mortalidad/docs/PatronesMortalidadEspana2012.pdf. Accessed 3 Feb 2016

- 33.Ferrer A, Formiga F, Cunillera O, et al. Predicting factors of health-related quality of life in octogenarians: a 3-year follow-up longitudinal study. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:2701–2711. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.