Abstract

Objective:

Although remarkable progress in the pharmacological components of the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and liver cancer has been achieved, HBV-related stigma is recognized as a major barrier to HBV management. The purpose of this Revised Social Network Model (rSNM)-guided review was to examine the existing research literature about HBV-related stigma among Asians and Asian immigrants residing in other countries.

Methods:

A scoping review of literature was conducted to determine the depth and breadth of literature. Totally, 21 publications were identified. The review findings were linked with the concepts of rSNM to demonstrate how individual factors and sociocultural contexts shape and affect the experience of HBV-related stigma.

Results:

Most studies were quantitative cross-sectional surveys or qualitative methods research that had been conducted among Chinese in China and in the USA. The three concepts in rSNM that have been identified as important to stigma experience are individual factors, sociocultural factors, and health behaviors. The major factors of most studies were on knowledge and attitudes toward HBV; only three studies focused on stigma as the primary purpose of the research. Few studies focused on the measurement of stigma, conceptual aspects of stigma, or interventions to alleviate the experience of being stigmatized.

Conclusions:

The scoping review revealed the existing depth and breadth of literature about HBV-related stigma. Gaps in the literature include lack of research address group-specific HBV-related stigma instruments and linkages between stigma and stigma-related factors.

Keywords: Asian, barriers to health services, hepatitis B virus, Revised Social Network Model, scoping review, socioculture, stigma

Introduction

Although Asian Americans are at lower risk for the most prevalent cancers, such as breast, lung, and colon cancers, experienced by most non-Asian Americans, they experience a significantly higher prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and the subsequent development of hepatocellular cancer.[1,2] Asian people with the HBV infection usually become infected during birth or from close family contact during early childhood and are at greater risk of developing long-term complications from the infection approximately 20 years earlier than people who become infected during adulthood.[3,4,5] Findings from studies of Asian Americans indicate that the prevalence of chronic HBV infection ranges from 4% to 15%,[1,2,6,7] which is more than 30 times the rate of 0.11% for non-Hispanic Whites.[8] Furthermore, HBV is responsible for 75%–90% of primary hepatocellular carcinoma cases worldwide.[8,9]

Due to the remarkable progress of the pharmacological prevention and treatment of HBV and liver cancer, great strides have been made in HBV and liver cancer management in the last three decades.[2,3] However, results of studies of HBV and other infectious diseases point to the fact that the health-related stigma associated with these diseases has a direct negative impact on quality of life as well as the process of health-care delivery and medical decision-making.[10,11,12,13] There is a long history of social discrimination against patients with such infectious diseases as leprosy, tuberculosis, and HIV.[10,11,12,13] Research findings have revealed that people living with infectious diseases frequently are marginalized and experience considerable stigmatization.[10,11,12] Hepatitis carriers have been described as modern-day “lepers”[14] or “AIDS,”[15] and individuals with HBV as well as their families have felt ashamed about having HBV.[14]

In his seminal work, Goffman initially defined stigma as “the situation of the individual who is disqualified from full social acceptance” (p. 9).[16] As the work about the concept of stigma has evolved, theorists and researchers have concluded that stigmatization not only applies to the stigmatized person but also manifests in the social context that defines an attribute as devaluating[17] and discriminating.[18] The devaluation of one's social identity can be a major cause of the individual's low self-esteem, particularly in his or her family.[14,15,18] Moreover, health-related stigmatization often results in social and financial marginalization and withholding of treatment or denial of services,[10,19] thereby violating the human rights of people with the HBV infection. HBV-related stigmatization may occur at family, community, or institutional level and may be perceived or expressed visibly or invisibly. Research that informs our understanding of the attributes and the consequences of HBV-related stigma is important. However, there are no literature reviews evaluating the effect of stigmatization related to HBV infection among Asians. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to report the results of a Revised Social Network Model (rSNM)-guided scoping review designed to examine the existing research literature about HBV-related stigma among Asians and Asian immigrants residing in other countries.

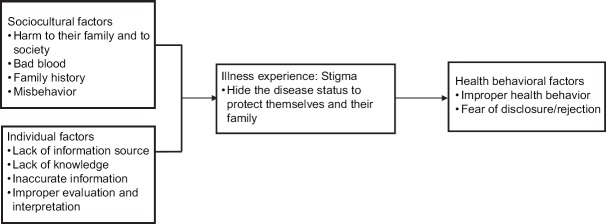

Conceptual model

The rSNM was selected to guide our understanding of how different sociocultural contexts shape and affect HBV-related stigma experiences. The concepts of this conceptual model are individual factors, sociocultural factors, health behavioral factor, and illness experiences. Individual factors account for person-centered influences such as knowledge, attitudes, or health belief. Sociocultural factors refer to characteristics including demographic, social, and cultural settings that form the background for people's lives. Health-related behaviors are action taken by a person which affect his or her health status.[20,21] Illness experience refers to the individual's experience of HBV infection, and HBV-related stigma is considered a part of the HBV illness experience. Stigmatization and stigma-related factors were extracted from the studies, and the findings were categorized as stigma experiences (such as social exclusion or discrimination) that caused from individual and sociocultural factors and resulted in health behavioral changes. These linkages are found in the results section of this paper.

Methods

A scoping review of literature was conducted to determine the depth and breadth of literature about HBV-related stigma. A scoping review is based on iterative, conceptual, and interpretative approaches that encompass both empirical and conceptual literature about broadly framed questions. A scoping review emphasizes the importance of developing a critique based on the relevance, credibility, and contribution of evidence rather than by rigidly determined methodological considerations of analysis and synthesis that is a hallmark of other types of systematic reviews of literature.[22,23] We identified two research questions for our scoping review: (1) What is HBV-related stigmatization? And (2) What are the correlates of HBV-related stigmatization among Asians?

Identifying relevant studies

To identify studies as comprehensively as possible, we searched for research evidence not only from electronic databases but also from the reference lists of all retrieved articles. Furthermore, a Google Scholar search and a search of the websites of several HBV-related organizations, including the WHO and the Hepatitis B Foundation were conducted.

Our electronic searches encompassed literature published between 1988 and 2016 and were conducted using PubMed, Medline, the Cochrane Library, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, PsycINFO, SocINDEX, and the Educational Resources Information Centre. The search terms were “stigma* or stigmatization or marginalization or shame AND hepatitis B AND Asia,” “stigma* or stigmatization or marginalization or shame or discrimination AND hepatitis B AND (various Asian countries).”

Inclusion criteria in search of both qualitative and quantitative studies were: (1) published as full text in the English language; (2) included Asian Americans or people from various Asian countries; (3) all age groups; (4) focused on HBV patients, families, communities, and health care providers; (5) focused on HBV-specific stigma.

Study selection

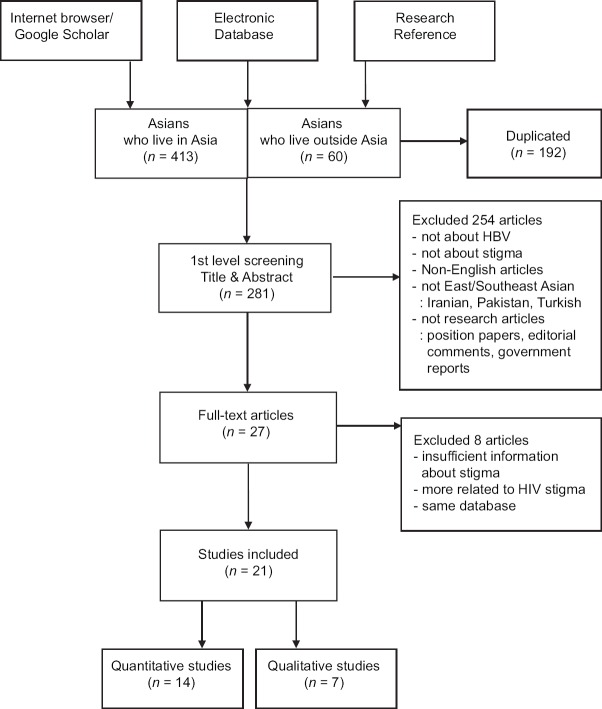

Figure 1 is a flow diagram of the search and selection of papers for the review. Although scoping review methodology does neither limit the reviews to research trials nor require quality assessment, we decided to carefully develop a selection process. Our initial perusal of the citations indicated that our search strategy yielded a large number of irrelevant studies. For example, we found many search results for HIV and HCV infections-related stigma. However, we did not want to filter out these articles in case, some of the articles focused on coinfections of HBV. Titles and abstracts were reviewed by two independent reviewers (Haeok Lee and Deogwoon Kim) to determine eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. Duplicated papers and papers that were commentaries, summary reports, or media reports were excluded. Full-text articles were obtained for 21 papers and were read in full by three authors (Haeok Lee, Jin Yang, and Deogwoon Kim).

Figure 1.

Scoping review flow diagram

Process of scoping: Narrative review and charting data

Based on preliminary trial charting and sorting according to key concepts/factors and themes, the literature was categorized according to the aims of the study, the type of study design, the study population, stigma definition, and stigma-related findings.

Collecting and summarization

The findings of the scoping review of literature are documented in Tables 1 and 2 and in the narrative text. A descriptive-analytical method was utilized to present a narrative account of the existing literature. The tables include the distribution of studies geographically, research methods, definition and measures used, participants, and dimensions of stigma or stigma-related factors; the studies are listed in the chronological order of publication date, from the most recent publication to the earliest. Categorization of findings was performed by the authors (Haeok Lee, Jin Yang, and Deogwoon Kim) and checked, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion among the three authors (Haeok Lee, Jin Yang, and Deogwoon Kim). Data charting tables [Tables 1 and 2] were developed to sort the extracted data and included charting of key features, and literature review was organized based on rSNM. For example, recording information about the dimension or definition of stigma or correlates of stigma or the impact of stigma on health or stigma intervention so that the findings were more contextualized and more understandable to readers.[22] Moreover, the findings of the literature review were organized and are depicted in Figure 2 based on rSNM to help better understanding of HBV-related stigma phenomenon.

Table 1.

Summary of quantitative studies

| Authors/Year/Geographic region | Study design | Sample | Stigma definition | Stigma-related variables/Other constructs | Stigma-related consequences/Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maglalang et al., 2015 CA, USA | Evaluation of San Francisco Hep B Free (SFHBV) intervention | Cantonese or English-speaking community dwellers (Asian) 40 in 2013 | “Saving face” | A cultural norm of maintaining a positive reputation that is seen as imperative for social acceptance and economic mobility | To increase awareness and to motivate people to seek treatment or screening for HBV Participants’ awareness of HBV was impacted by SFHBV campaign. |

| Yu et al., 2015 China | Survey design | Community dwellers 6,538 from 42 villages | Yes: negatively judging and unfairly treating. A part of attitude toward HBV patients and carriers |

Fear of infection Knowledge about transmission HBV vaccination status |

Tried to avoid: accepting gift hugging/shaking hands having dinner together children playing together children marrying with HBV infected person |

| Carabez et al., 2014 CA, USA | Descriptive survey design | HBV infected patients 60 Chinese 27 Japanese 17 Korean 11 Vietnamese 9 Filipino 10 mixed Asian |

No | Knowledge Fears of liver cancer |

Stigma is not a main purpose. Fears of transmission to loved ones and social stigma |

| Dahl et al., 2014 Australia | Prospective design | 55 HBV patients 13 Chinese 5 Malaysian 4 Vietnamese 3 Filippino 2 Burman Others |

No A part of knowledge |

Knowledge | 95% felt comfortable to tell a family member. 35% felt comfortable to tell friends and coworkers. |

| Shi et al., 2013 China | Survey design | 724 College students | Yes: Link & Phelan's definition. | HBV blood test results HBV-infected family member or friend |

Labeling Stereotyping Separating Discrimination |

| Eguchi & Wada, 2013 Japan | Cross-sectional design | 3,129 workers | No A part of attitude 2 items to measure |

Attitudes toward HBV- and HCV-infected colleagues | Had prejudiced opinions Avoided contact with infected colleagues Knowledge was associated attitudes. |

| Cotler et al., 2012 IL, USA | Survey Design | 201 Chinese HBV carriers 16% HBV vaccinated 36% 11/32 had family history of HBV |

Yes: 5 domains; negative perception, social isolation, fear of contagion, healthcare neglect, workplace/school stigma | HBV stigma: HBV carriers bring trouble to their families and harm others | 70% believed that HBV carriers put others at risk. 62% agreed that HBV carriers should subsequently avoid contacting with others. |

| Li et al., 2012 Canada | Survey Design | 343 Chinese | Yes: Goffman's definition and the Toronto Chinese HBV Stigma Scale (20 items) | Knowledge | Fears of the consequences and contagiousness of HBV play a role in the development and perception of HBV stigma. |

| Maxwell et al., 2012 CA, WA, DC, USA | Correlational Design | 653 Vietnamese 260 Homing 493 Korean 329 Cambodian |

No 1 item to measure | Knowledge Awareness Susceptibility Severity |

38% Vietnamese, 55% Hmong, 47% Korean, and 70% Cambodian believed that people avoid people with HBV (stigma). Respondents with higher knowledge scores were more likely to agree that people avoid people with HBV (stigma). |

| Yoo et al., 2012 CA, USA | Community intervention | 23 individuals of Asian American community (community members, health care providers, community leaders) | No | HBV associating with “bad people” and “bad behavior” | |

| Guirgis et al., 2011 Australia | Descriptive study | 60 HBV patients 24 Chinese 3 Hong Kong 33 Others |

No 1 item to measure | Perception of HBV | 53% reported fear of discrimination/stigma. |

| Mohamed et al., 2012 Malaysia | Cross-sectional design | 483 chronic HBV patients 353 Chinese 109 Malaysian 12 Indian 9 Others |

No A part of attitude |

Knowledge Attitude toward HBV |

69% worried about spreading virus to family members and friends. 34% felt embarrassed to disclose their disease status. 34% were against having HBV patients work in food industry. |

| Wang et al., 2009 Taiwan | Cross-sectional design | 328 college students 106 chronic HBV 113 susceptible 109 immuned |

No | Knowledge Health belief Self-efficacy of HBV prevention |

Afraid to disclose infection status to friends Afraid to acquire infection from infected friends |

| Lai & Salili, 1999 China | Cross-sectional and comparison design | 90 mothers 30 with healthy children 60 with HBV-infected children |

No A part of attitude |

Parenting stress Attitudes toward HBV children |

Mothers of healthy children disagreed with the idea of integrating HBV children into ordinary schools. They thought that HBV would be transmitted and HBV infected children are inferior having low self-esteem. |

Table 2.

Summary of qualitative studies

| Authors/Year/Geographic regiosn | Design | Sample | Purpose | Categories or factors | Stigma-linked themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al., 2014 CO, Northeast,& MA, USA | Individual interview/Focus group interview | Community health leaders: 9 Koreans 14 Khmers |

To explore factors influencing HBV and liver cancer prevention health behavior within the sociocultural contexts of CAs and KAs | Sociocultural Socio-medical Socio-linguistic Socio-resource Individual Health-related behavioral |

Individual factor: perceived transmission of HBV as a “contagious” or “contaminant.” KAs tend to emphasize sanguinity and family history, whereas CAs blame the unhealthy environment during Khmer rouge era and in refuges campus |

| Ng et al., 2013 Malaysia | Focus group interview | 44 HBV-infected patients from an outpatient clinic | To capture the experience of people with chronic HBV when they were first diagnosed | Patients’ feelings, reactions, and coping strategy Patients’ needs |

Individual factor: fear of being discriminated by or causing anxiety to their social contacts. “I didn’t dare to let anyone know. I was afraid that people will be scared of me. I only let my family know. Not even my friends know.” Health bevavioral factor: “I can drink yours but you cannot drink mine.” “So we kept separate bowls, spoons, everything also separate.” |

| Philbin et al., 2012 MD, USA | Focus group interview | 58 Asian immigrants 20 Chinese 19 Korean 19 Vietnamese |

To explore knowledge, awareness, and perceived barriers toward HBV screening and vaccination | Stigma Knowledge Awareness; Susceptibility Factors affecting screening and vaccination Cultural barriers to prevention Health care system |

Stigma theme was repeatedly raised across groups as a barrier to liver cancer prevention. Health behavioral factor: accessing care was a potential problem from the perspective of stigma since it can make it more difficult to keep one's status secret. Sociocultural factor: there were relatively high levels of discrimination from community. For example, afraid of having a pamphlet in their possession would make others think they were HBV carriers. |

| Russ et al., 2012 CA, USA | Semi-structured interview | 23 providers 17 HIV positive patients with HBV or HCV co-infection 7 Filipino 6 Chinese 3 Vietnamese 1 Indonesian |

To identify barriers to care and treatment in API with HIV and without hepatitis co-infection | Stigma Individual and structural barriers to care | For both patients and providers, stigma was the most commonly recognized barrier to care. Stigma can create additional barriers for clients seeking ethnically/linguistically specific care and for providers within the Asian American community interested in filling this gap in care. Individaul factor: co-infected patients may be willing to talk about their HIV status but tend to compartmentalize their conditions and avoid disclosing their hepatitis infection. Sociocultural factor: stigma associated with HIV and hepatitis co-infection in Asian community extends to the stigmatization of physicians who provide HIV services. Health behavioral factor: providers indicate that not only clients avoid providers who might be able to identify them but these clients also avoid places where they might be identified by members of their community. |

| Lee et al., 2011 CO & Northeast, USA | Semi-structured face-to-face interview | 18 Korean with HBV infection | To seek real-world data about factors influencing the recognition and management of HBV infection | Sociocultural meaning Layman's construction of the cause Misunderstanding and cultural learning styles Personal and environmental barriers |

The socio-cultural meaning of disease: the patients reported many negative perceptions and experiences in living with the virus since stigma related to HBV infection status is commonly found in Asian communities due to misunderstandings about the transmission route of HBV. Thus, patients hid the disease. Individual factors: perceived not just a blood-transmitted disease but a blood-borne disease; reluctant to share their condition with others who were not family. Sociocultural factor: HBV was socially perceived as “causing harm to family and to society.” People think HBV is a contagious disease. It is bad blood like AIDs. Afraid that if people know their conditions, they would not eat with them. |

| Wallace et al, 2011 Australia | Face-to-face semi-structured interview/focus group discussion | 40 community health workers 20 HBV patients 6 Vietnamese 5 Chinese 3 Khmer 6 Others |

To develop a comprehensive public health response to hepatitis B in Australia | Disclosure Clinical management Participants’ beliefs and concerns about HBV infections |

Selective disclosure: disclosure was not easy for all people that we spoke with. Some respondents talked of complex rules about disclosure for different friends and family members in different situations. The fear of rejection or stigma at a personal and community level was identified as an important issue that restricted individual disclosure. Sociocultural factor: the impact of chronic HBV diagnosis and subsequent disclosure of this information within some communities can lead to exclusion from family and community life. Health behavioral life: HCP noted less stigma related to HBV in comparison to other sexually transmitted diseases. |

| Lee et al., 2010 Korea | Face-to-face interview | 9 Koreans with HBV infection | To explore infected Korean's perspective's, knowledge, and experiences of living with a HBV diagnosis | I am just a carrier, no harm Experience of living with an invisible virus Misunderstanding and its impact on health and social life Management of chronic HBV |

Misunderstanding and its impact on health and social life: the participants linked their infection to family history by identifying family members who were diagnosed with liver disease and died from liver cirrhosis or liver cancer. Sociocultural factor: “People think HBV is a contagious disease. It is transmitted through food, a cup of alcohol, or other things. Like AIDs, people misunderstand and have a wrong view about HBV infection.” “I am not at the stage I need to reveal my infection condition to others. I feel bad when sharing food with friends.” |

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for HBV-Related stigma

Results

Research methods

Table 1 presents the quantitative studies and Table 2 presents qualitative studies. As can be seen by reviewing both tables, most studies were cross-sectional surveys that had been conducted in China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, USA, Canada, and Australia; the majority of the studies was conducted outside Asia. As shown in Table 2, various qualitative methods were used, including open-ended interviews, focus groups, grounded theory, semi-structured and in-depth interviews, and ethnography. Most studies focused on knowledge of and attitudes about HBV. Only three studies[24,25,26] focused on stigma as the primary purpose of the research. In the cross-sectional surveys reviewed, only three studies[24,26,27] included dimensions of stigma. The other studies did not include an explicit definition of stigma or a theoretical frameworks that might have guided the research, including the way in which stigma was measured. HIV- or HCV-related stigma, rather than, HBV-related stigma, was the main focus of the studies that included the coinfections of HIV, HCV, and HBV. Only two articles report of experimental research of the effects of interventions on overall management of HBV; both studies were conducted in the USA and by the same research group.

Participants

Participants were convenience samples of patients utilizing Asian-serving clinics, people who were members of Asian serving community organizations, or people attending community events. Chinese people in China and in the USA were the most studied groups.[24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] The participants were HBV-infected patients, members of the general community, health-care providers, or community leaders [Tables 1 and 2]. All participants were adults. Only seven studies[24,26,27,28,31,34,36] included a report of the response rate and one study[34] included a report of response rates below 40%. None of the researchers used online recruitment methods.

Stigma experiences

Literature revealed that HBV-related stigma is subjective and internalized, perceived, or experienced by individuals, in interpersonal interactions (or face-to-face) or in the larger society. A general consensus exists about the definition of stigma as a negative perception with fear of rejection at both personal and family levels and which cause harm to both the family and the society. Stigma prevented both individuals and their family members to disclose the presence of HBV infection because they feared discrimination from the society.[15,25,28,31,32,33,34,37,38] Reports of indicators of stigma ranged from 24%[36] to 70%.[39] In most studies, stigma was regarded as a dimension of knowledge of and/or attitude about HBV. Community members, community leaders, health care providers, and college students were identified as groups who stigmatize the HPV-infected persons. Only two studies[24,26] included multidimensional measures of stigma and only one study[26] was a report of the development of stigma measures, including psychometric properties but only for Chinese Americans.

Public or societal stigma related to HBV infection status is commonly found in Asian countries and Asian communities in the US and has been perceived and/or experienced as social exclusion or discrimination. Stigma may be experienced when family or social norms are internalized. For example, in some qualitative studies, the participants perceived themselves as being referred to in terms such as having “bad blood” or having “bad gene” or “being contaminated” or “misconductedness.”[15,37,40,41] This self-devalued quality of one's social identity inflicts damage on one's self-esteem.[15] Interpersonal or face-to-face stigma may be experienced through encounters with the family or through interpretation of family experiences. Despite the heterogeneity of Asian ethnicities, most Asian cultures have common several cultural values such as interdependence, collectivism, and family centeredness.[15,42] Given the collective nature of Asian cultures, having HBV is a reflection on the family rather than the individuals, and families with an HBV-infected member may perceive or encounter public stigma or losing family face.[15] The threat of social stigma may prevent people living with HBV from revealing their status to others.

The definition of HBV-related stigma found in the literature was varied reflecting the different perspectives of the stigma found in different sociocultural contexts and/or with different populations that were the focus of the particular study. HBV-related stigma was reported by patients, community members, and health-care professionals. Based on the literature review, HBV-related stigma has been defined as a multidimensional concept including social, interpersonal, and personal stigma. It is a perceived and experienced (enacted) phenomenon and results from a perception of how others (including family members) view the stigmatized person and can result from and it related to poor health behavior.

The causes of stigma

The causes of stigma were attributed to both individual and sociocultural factors in various studies [Tables 1 and 2]. Maxwell et al. found that knowledge and awareness levels of HBV infection were associated with stigma across 4 community-based surveys from 38% to 70%.[39] Fear of HBV infection is the most common cause of HBV stigma.[24,27,33,35,38,43] A lack of knowledge and awareness of HBV often resulted in a misunderstanding of the disease and results in the stigmatization of one's own self or stigmatization of people infected with HBV.[15,24,27,28,29,32,41] The findings of both quantitative and qualitative studies revealed that most Asian or Asian Americans including health-care providers stated that sharing of contaminated food and eating utensils was the most common route of HBV transmission.[15,27,31,32,33,34,37] Between 38% and 70% respondents believed that HBV carriers put others at risk, expressed their intention to avoid them, and supported their isolation.[24,39] Similarly, HBV-infected participants expressed fears of transmitting the virus to loved ones through casual contact.[43]

Furthermore, culture influences the meaning or beliefs that individuals attach to HBV and can cause stigma experiences.[29,33,41] In Asian sociocultural context, HBV is often viewed as harmful to society or to the family, and HBV-positive status wrongly stigmatizes family members and increases the fear of “loss of face.”[15] A person who “loses face” can no longer function well in his or her social network and, for example, can influence other's beliefs about the social acceptance of an individual or his/her family for marriage or employment.[35,38]

Health outcome of stigma

Participants in both qualitative and quantitative studies experienced HBV-related stigma both personally and socioeconomically. The stigma affected admission to certain schools or parental rejection at schools and resulted at a time in loss of employment.[30,43] Another outcome is that HBV-related stigma on both personal and family levels acts as an impediment to marriage and having children.[15,35] The findings of qualitative studies indicated that HBV-related stigma is a serious barrier to accessing services.[25,33] It was found that HBV-positive individuals were more likely to disclose to the family but reluctant to disclose their condition to friends and coworkers.[28,32] Two studies reported that the individuals who did not disclose their HBV status to others reported higher perception of stigma.[38,39] Only two quantitative studies included examination of the relation between HBV stigma and health care including blood screening and other health behaviors.[26,27]

In summary, the review suggests that HBV-related stigma is a part of the illness experiences resulting from a perception of how others (including family members) view them. Stigma can also negatively affect the health and health behaviors [Figure 2]. The three concepts in rSNM that have been identified as important to the stigma experience are individual factors, sociocultural factors, and health behaviors and confirms that the way people perceive or respond to HBV is as much as a sociocultural process as it is a result of individual actions.

Discussion

Our findings point to the fact that stigmatization is caused by individual and sociocultural factors, and that stigmatization not only occurs for the HBV-infected person but also is manifested in a social context in which discrimination against or devaluation of both patients and family occurs. In addition, institutional disadvantages caused by societal stigmatization are placed on stigmatized persons creating barriers to their receiving HBV blood screening and HBV management. The studies in China confirmed that HBV-infected individuals are regarded by the society as having a disgraced moral status and are banned from the society including workplaces and schools.[26,30,35] Clearly, we need to examine the experience of stigma not only among individuals with HBV infection but also among HBV-infected families and health-care professionals within their sociocultural contexts.

The outcomes of stigma for HBV-infected people are important to understand because they will become not only obstacles for liver cancer prevention and treatment of infected individuals but also risks for others. If infected individuals are not aware of their infection or misunderstand how HBV is transmitted, they will unintentionally infect others as well as not receive appropriate health management. The loss of family, friends, community, and health care and the loss of employment result in infected individuals feeling rejection, marginalization, and discrimination. For example, in China and Korea, there is pervasive discrimination against people who suffer from chronic HBV infection. HBV-infected children are frequently expelled from schools and adults fired from jobs.[2] They are shunned by other community members despite recent national antidiscrimination efforts.[44,45] In a 2007 survey covering 10 major cities in China, hepatitis B was cited as one of the top three reasons for job discrimination.[46]

The scoping review is a novel approach to provide a rigorous and transparent method for mapping areas of research including the volume, nature, and characteristics of the primary research. It allows us to identify the gaps in the evidence, summarizing and disseminating findings as Arksey and O’Mally claimed.[22] The results of our scoping review of literature suggest that there is a great need for more research to increase our understanding of the phenomenon of stigma among Asian HBV-infected people and their family members. For example, the correlational and longitudinal evidence is now needed to establish linkage and causality between stigma and HBV and liver cancer management behaviors. This will open a new line of research in liver cancer prevention and HBV management that will benefit the substantially underserved and understudied Asians in both Asian countries and where Asian immigrants reside more broadly. Since HBV requires a relatively long course of treatment and regular screening, stigma constitutes an obstacle to continuing or remaining in treatment.[33] Quantitative measures used in studies are largely attitude or knowledge scales or contain one item measuring the broad and general negative feeling toward HBV-positive people. Thus, to more accurately explore the sources and consequences of HBV stigma, it is imperative to develop a culture-specific multidimensional HBV stigma instrument. Data collected from the use of this instrument will prepare the way for effective HBV stigma interventions.

Both individual and community-level interventions to reduce the burden of HBV-related stigma are necessary in both Asian countries and where Asian immigrants reside. Given the deeply ingrained HBV-related stigma among many Asians in Asia, it is not surprising that many Asian immigrants remain reluctant to undergo testing or to seek medical attention for a positive test result even after moving to the USA or another Western country.[33] Because avoidance of HBV testing and management is due largely to a lack of knowledge about the routes of HBV transmission and means of prevention as well as social stigmatization of the disease,[15,33,40] it is imperative to develop and implement targeted group-specific public health educational interventions.

Conclusion

HBV-related stigma presents as a part of the HBV illness experience and is a perceived and experienced multidimensional phenomenon and is a complex social process. It is likely to impede participation in health care. There are significant gaps in the literature. The majority of the studies included in our review were descriptive or cross-sectional. Studies of stigma from other infectious diseases revealed that different sociocultural contexts contribute substantial variation in the construction of stigma. However, only one study to date has focused on studying the HBV-stigma from the perspective of the Chinese subgroup of Asians.[24] Future longitudinal and multi-Asian subgroup level research is needed and should be based on target-group-specific stigma definitions and measures as well as relevant theory. Thus, the development of a culturally relevant and acceptable psychometric instrument that measures HBV-related stigma and stigma-related factors among other Asians is a critical step for understanding the mechanisms that underlie relation between HBV-related stigma, culture, and health behavior.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services. Combating the Silent Epidemic of Viral Hepatitis: Action Plan for the Prevention, Care & Treatment of Viral Hepatitis. 2014. [Last cited on 2016 Oct 11]. Available from: https://www.aids.gov/pdf/viral-hepatitis-action-plan.pdf .

- 2.Institute of Medicine [IOM]. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. 2010. [Last cited on 2016 Oct 11]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/pdfs/iom-hepatitisandlivercancerreport.pdf .

- 3.Chae HB, Hann HW. Time for an active antiviral therapy for hepatitis B: An update on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3:605–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim CY, Kim JO, Lee HS, Yoon YB, Song IS. Natural course and survival of chronic hepatitis B and liver cirrhosis in Korea: Observation of 20 years. Korean J Med. 1994;46:217–29. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin X, Robinson NJ, Thursz M, Rosenberg DM, Weild A, Pimenta JM, et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the Asia-Pacific region and Africa: Review of disease progression. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:833–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kowdley KV, Wang CC, Welch S, Roberts H, Brosgart CL. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology. 2012;56:422–33. doi: 10.1002/hep.24804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H, Levin MJ, Kim F, Warner A, Park W. Hepatitis B virus infection among Korean Americans in Colorado: Evidence of the need for serologic testing and vaccination. Hepat Mon. 2008;8:91–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ioannou GN. Hepatitis B virus in the United States: Infection, exposure, and immunity rates in a nationally representative survey. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:319–28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization [WHO]. Cancer. (Fact Sheet No. 297) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Last updated on 2016 Oct 11]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: Systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18640. doi: 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieber E, Li L, Wu Z, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Guan J National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Collaborative HIV Prevention Trial Group. HIV/STD stigmatization fears as health-seeking barriers in China. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:463–71. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9047-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mak WW, Mo PK, Cheung RY, Woo J, Cheung FM, Lee D. Comparative stigma of HIV/AIDS, SARS, and tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:1912–22. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J, Somma D. Health-related stigma: Rethinking concepts and interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:277–87. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zickmund S, Ho EY, Masuda M, Ippolito L, LaBrecque DR. “They treated me like a leper”. Stigmatization and the quality of life of patients with hepatitis C. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:835–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H, Hann HW, Yang JH, Fawcett J. Recognition and management of HBV infection in a social context. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:516–21. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goffman E. Stigma and social identity. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. 1. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1963. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. In: Social stigma. The Handbook of Social Psychology. Gilber DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. Vol. 2. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1998. p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rintamaki LS, Davis TC, Skripkauskas S, Bennett CL, Wolf MS. Social stigma concerns and HIV medication adherence. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:359–68. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee H, Fawcett J, Yang JH, Hann HW. Correlates of hepatitis B virus health-related behaviors of Korean Americans: A situation-specific nursing theory. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2012;44:315–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2012.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pescosolido BA. Illness careers and network ties: A conceptual model of utilization and compliance. Adv Med Sociol. 1991;2:161–84. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arksey H, O’Mally L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies. A review of the nursing literature? Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:1386–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cotler SJ, Cotler S, Xie H, Luc BJ, Layden TJ, Wong SS. Characterizing hepatitis B stigma in Chinese immigrants. J Viral Hepat. 2012;19:147–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2011.01462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russ LW, Meyer AC, Takahashi LM, Ou S, Tran J, Cruz P, et al. Examining barriers to care: Provider and client perspectives on the stigmatization of HIV-positive Asian Americans with and without viral hepatitis co-infection. AIDS Care. 2012;24:1302–7. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.658756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi J, Chyun DA, Sun Z, Zhou L. Assessing the stigma toward chronic carriers of hepatitis B virus: Development and validation of a Chinese college students’ stigma scale. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;43:E46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li D, Tang T, Patterson M, Ho M, Heathcote J, Shah H. The impact of hepatitis B knowledge and stigma on screening in Canadian Chinese persons. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:597–602. doi: 10.1155/2012/705094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dahl TF, Cowie BC, Biggs BA, Leder K, MacLachlan JH, Marshall C. Health literacy in patients with chronic hepatitis B attending a tertiary hospital in Melbourne: A questionnaire based survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:537. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guirgis M, Nusair F, Bu YM, Yan K, Zekry AT. Barriers faced by migrants in accessing healthcare for viral hepatitis infection. Intern Med J. 2012;42:491–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai AC, Salili F. Parental attitudes toward their parenting styles and children's competence in families whose children are hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers in Guangzhou China. J Comp Fam Stud. 1999;30:281–95. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohamed R, Ng CJ, Tong WT, Abidin SZ, Wong LP, Low WY. Knowledge, attitudes and practices among people with chronic hepatitis B attending a hepatology clinic in Malaysia: A cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:601. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng CJ, Low WY, Wong LP, Sudin MR, Mohamed R. Uncovering the experiences and needs of patients with chronic hepatitis B infection at diagnosis: A qualitative study. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2013;25:32–40. doi: 10.1177/1010539511413258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philbin MM, Erby LA, Lee S, Juon HS. Hepatitis B and liver cancer among three Asian American sub-groups: A focus group inquiry. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14:858–68. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9523-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wallace J, McNally S, Richmond J, Hajarizadeh B, Pitts M. Managing chronic hepatitis B: A qualitative study exploring the perspectives of people living with chronic hepatitis B in Australia. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:45. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu L, Wang J, Zhu D, Leng A, Wangen KR. Hepatitis B-related knowledge and vaccination in association with discrimination against Hepatitis B in rural China. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:70–6. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1069932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eguchi H, Wada K. Knowledge of HBV and HCV and individuals’ attitudes toward HBV- and HCV-infected colleagues: A national cross-sectional study among a working population in Japan. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee H, Yang JH, Cho MO, Fawcett J. Complexity and uncertainty of living with an invisible virus of hepatitis B in Korea. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25:337–42. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang WL, Wang CJ, Tseng HF. Comparing knowledge, health beliefs, and self-efficacy toward hepatitis B prevention among university students with different hepatitis B virus infectious statuses. J Nurs Res. 2009;17:10–9. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0b013e3181999ca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maxwell AE, Stewart SL, Glenn BA, Wong WK, Yasui Y, Chang LC, et al. Theoretically informed correlates of hepatitis B knowledge among four Asian groups: The health behavior framework. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:1687–92. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.4.1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee H, Kiang P, Chea P, Peou S, Tang SS, Yang J, et al. HBV-related health behaviors in a socio-cultural context: Perspectives from Khmers and Koreans. Appl Nurs Res. 2014;27:127–32. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoo GJ, Fang T, Zola J, Dariotis WM. Destigmatizing hepatitis B in the Asian American community: Lessons learned from the San Francisco Hep B Free Campaign. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:138–44. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang LH, Kleinman A. ‘Face’ and the embodiment of stigma in China: The cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carabez RM, Swanner JA, Yoo GJ, Ho M. Knowledge and fears among Asian Americans chronically infected with hepatitis B. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:522–8. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0585-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.China Digital Times. China News Tagged with: Hepatitis B. [Last updated on 2009 Jul 29; Last cited on 2016 Jun 10]. Available from: http://www.chinadigitaltimes.net/china/hepatitis-b/

- 45.Jung EJ. Is Cheolsoo an Inferior to Others Because he is a HBV Carrier? [Last cited on 2016 Jun 10]. Available from: http://www.h21.hani.co.kr/arti/special/special_general/33067.html .

- 46.Weifeng L. Discrimination in Job Market Common: Survey. China Daily. 2007. Jun 14, [Last cited on 2016 Jun 10]. Available from: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2007-06/14/content_893811.htm .