ABSTRACT

T Lymphocytes face pathologically low O2 tensions within the tumor bed at which they will have to function in order to impact on the malignancy. Recent studies highlighting the importance of O2 and hypoxia-inducible factors for CD8+ T-cell function and fate must now be integrated into tumor immunology concepts if immunotherapies are to progress. Here, we discuss, reinterpret, and reconcile the many apparent contradictions in these data and we propose that O2 is a master regulator of the CD8+ T-cell response. Certain T cell functions are enhanced, others suppressed, but on balance, hypoxia is globally detrimental to the antitumor response.

KEYWORDS: Cancer, CD8+ T cell, CTL, hypoxia, normoxia, oxygen, physioxia, tumor

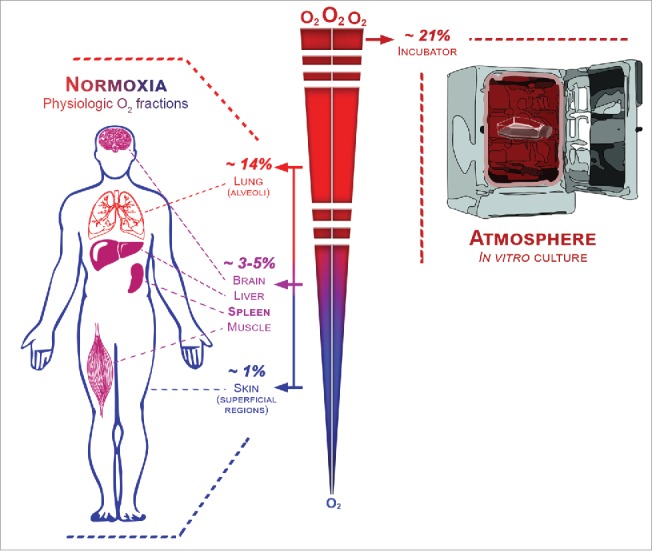

Oxygen levels and hypoxia

Oxygen availability has led to an important step in the evolution of life: aerobic respiration, an extremely efficient energy-producing process. Despite evolutionary pressure to provide O2 to most organs and cells in sufficient quantities, mammalian tissue vascularization is variable, with wide differences in proximity to the main source of O2 (i.e., blood from the aorta artery). As a consequence, the physiological O2 fractions (i.e., normoxic values of O2) found in the body significantly vary between tissues and within the same tissue (Fig. 1).1-3 Indeed, whereas the maximum value of O2 found in the body reaches 14.5% in pulmonary alveoli, only around 1% O2 is found in superficial region of the skin. Migratory immune cells clearly cope with such physiological variation in O2 supply, but in pathological conditions of inflammation, infection, and malignancy,4-7 O2 fractions are far below normoxic values, which represent the so-called hypoxic status.

Figure 1.

The range of physiological oxygen fractions found in the body.

Hypoxia, tumors, and the antitumor immune response

Hypoxic areas can often be found within solid tumors and were described to be negatively correlated with patient survival.8 Hypoxia has been shown to have a broad impact on tumor cells and on different actors of the antitumor response: It promotes tumor cell stemness, migration, metastasis, and resistance to radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and to CTL- and NK-mediated lysis.9-12 Direct effects on antitumor immunity have been widely studied for innate immune cells, with a major impact noted on tumor-associated macrophage polarization, DC modulation, and myeloid-derived suppressor cell -mediated immunosuppression.2,4,13,14 For T cells, the promotion of Treg accumulation and the Treg/Th17 balance have been intensively studied.2,13,15 However, for CD8+ CTL, our understanding of the impact of hypoxia is less comprehensive and has been gathered through very indirect methodology. Here, we focus on these critical cells for antitumor function and we discuss issues that may help to reconcile certain contradictory results.

The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway, more than a simple hypoxia story

The hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway has been described to be the main regulator in the cell response to hypoxia.16 HIFs are heterodimers composed of a constitutive β subunit (usually HIF-1β) together with an inducible α subunit (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, or HIF-3α). Under normoxia, prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing (PHD) enzymes, which need O2 as a cofactor, will hydroxylate the α subunit, leading to its degradation after VHL-dependent ubiquitylation, or its inactivation through FIH-dependent ubiquitylation. Conversely, under hypoxia, the α subunit is stabilized and complexes together with the β subunit. Subsequently, it translocates into the nucleus and transcribes various genes that have a hypoxia-responsive element sequence in their promoter. Under limiting O2 tensions, the main targets are genes involved in angiogenesis (to increase O2 supply) and glycolysis (cells can no longer rely on O2-dependent oxidative phosphorylation for energy production).

One approach that has been used to indirectly investigate the impact of hypoxia on the cellular response is to stabilize HIF (e.g., through drug targeting or genetic engineering). However, it is not clear whether strategies that aim at modulating expression of VHL or PHD are HIF-specific, as these enzymes were described to play a role in other pathways.17,18 Another consideration when modulating HIF is that T cells, which have a complex signaling machinery associated with metabolic reprogramming, were shown to stabilize HIF even under atmospheric O2 fractions (i.e., ∼21% O2) after TCR stimulation in vitro.19-21 Of interest, even if this observation might be an artifact of in vitro culture, it could also result from the characteristic clustering of T cells observed after activation and the generation of localized areas of low O2 tensions in the cluster, due to increased O2 consumption in a confined space. Thus, localized decrease in O2 availability and HIF activity could directly link two typical features of activated T cells: clustering after activation and switching from oxidative phosphorylation toward aerobic glycolysis.22,23

In addition to the complexities of trying to infer the impact of hypoxia through HIF pathway modulation, certain cellular responses to hypoxia were shown to be HIF independent.18,24,25 Therefore, we consider that solely modulating the HIF pathway cannot fully decipher the overall impact of hypoxia. However, combining HIF modulation together with oxygen level manipulation is an important approach to identify any hypoxia effect mediated by HIF.

Manipulating oxygen levels in vitro: Normoxia matters

Direct manipulation of O2 levels in vitro has the advantage of recapitulating the predicted in vivo O2 deprivation, leading to both HIF-dependent and HIF-independent mechanisms. In order to study the impact of hypoxia by modulating O2 fractions in vitro, one needs to compare a hypoxic condition to a normoxic control.

In most studies that manipulate O2 levels in vitro, a comparison is made between cells cultured at ≤1% of O2, as hypoxia, to cells cultured in a classical incubator where O2 fractions are close to the atmospheric value (i.e., ∼21%), as normoxia. However, the atmospheric O2 fraction is not physiologically relevant as a normoxic control, since normoxia found in the body is far below this value (Fig. 1).1-3 In order to make hypoxia studies more physiologically valid, we consider that the physiological normoxic O2 fraction used for comparison should correspond to the healthy tissue for the cell type being studied. This O2 fraction is often termed “physioxia,”3,21 in order to differentiate this condition from the 21% value that is erroneously considered as normoxia. Indeed, several key studies have clearly demonstrated that the conventional culture of T cells in vitro under atmospheric O2 fractions poorly reflected in vivo function, as compared to physiological normoxia.26-28 This choice of normoxic reference point is also critical for interpreting whether a cellular response is truly a hypoxia response, or a normal physiologic response. Many T cell functions in the healthy body occur at a physiologic O2 fraction of 5%; such a response could be falsely interpreted as a hypoxia response if compared to culture under 21% O2.

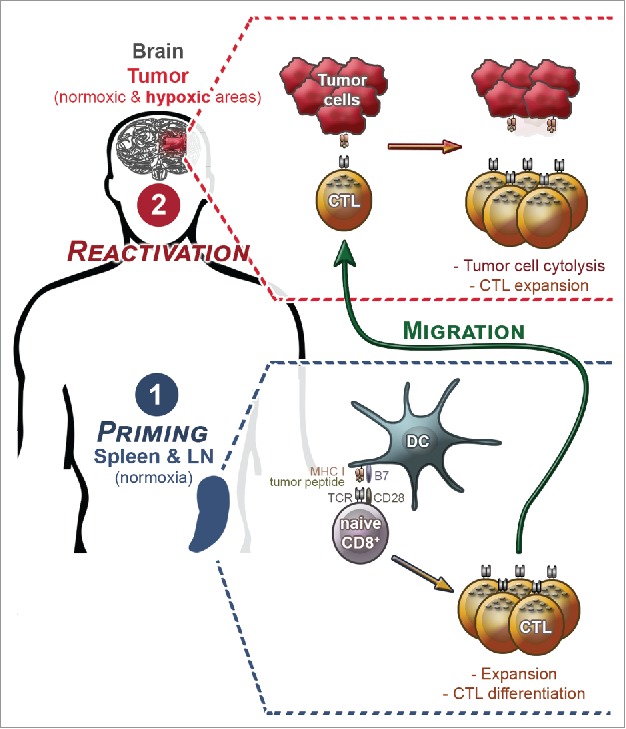

The importance of the CD8+ T-cell differentiation stage

A major consideration in understanding CD8+ T cell function under hypoxia is the differentiation state of the cell. Antigen-experienced CD8+ T cells (i.e., effector and memory CD8+ T cells) will experience the widest range of O2 tensions, including extreme hypoxia as they migrate and infiltrate hypoxic zones within the tumor site. In contrast, the priming of naïve CD8+ T cells will occur principally in non-hypoxic secondary lymphoid organs (Fig. 2). This aspect must be considered when interpreting in vitro studies in which naive T cells are primed under hypoxia: This condition would be rarely encountered in vivo. Moreover, already primed CD8+ T cells have distinct requirements for activation and possess their own metabolic programs,29,30 underlining the importance of distinguishing T differentiation state rather than generalizing the consequences of hypoxia for CD8+ T cells. Notwithstanding these aspects, it is highly relevant to study the priming of CD8+ T cells under low O2 fractions (e.g., ∼5% O2), which are routinely found in secondary lymphoid organs.

Figure 2.

The two main steps in a CD8+ T-cell response against a solid tumor (illustrated here for a brain tumor): priming and reactivation. In secondary lymphoid organs, where oxygen fraction is normoxic, naive CD8+ T cells are primed after recognition of a MHC class I/ tumor peptide complex presented by dendritic cells. This leads to expansion and differentiation into CTLs. After migration to the tumor site, CTLs recognize tumor cell leading to tumor cell cytolysis and CTL expansion. At this reactivation step, CTL will face normoxia and hypoxia.

Low oxygen fractions and T-cell priming

Different consequences of lowering O2 fractions below atmospheric have been observed at the priming stage of naïve T cells; a few studies found that this was beneficial or had no impact on T-cell expansion,31-36 but most reports showed that lowering O2 fractions in vitro decreases cell proliferation and increases cell death;26-28,37-42 the responsible mechanisms will be discussed in the next section. Similarly, analyses of the cytokine secretion pattern gave different results according to the study, with either increased IFNγ, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, MCP-1, and TNF-α secretion under lowered O2 fractions, or a decrease of some of the same cytokines (IFNγ, IL-2, IL-10, and TNF-α) in other studies.28,31-33,35,36,39,40 These inconsistencies could be explained by differences in the methodology such as the source and type of cells (e.g., human/mouse, primary/cell line, PBMC, spleen, CD4+, and CD8+), the timing for analysis after activation, the activation stimulus, and the percentage of O2 used. Species differences (mouse/human) remain to be fully elucidated, with different alternative isoforms of HIF-1α present in T cells from mouse (exon I.1) and human (exon I.3).43,44 The presence or absence of APCs (and other third-party cells) in the assay can modify the impact of O2 on T cell, since it was shown that O2 can impact DC maturation status and cytokine secretion profile.14 Another aspect is the timing after activation, since it has been described that HIF-1α is mainly stabilized in an acute manner, whereas HIF-2α is reported to be stabilized in a chronic manner;8,45 this could lead to distinct effects because of the different targets of these isoforms.46,47 Furthermore, HIF-1α or HIF-2α usage is dependent on the O2 fraction utilized, since lower O2 concentrations promote stabilization of HIF-1α as compared to HIF-2α. Indeed, very low concentrations of O2 (favoring HIF-1α stabilization) are less likely to be encountered in secondary lymphoid organs where T-cell priming occurs. Finally, although both TCR-independent and TCR-dependent stimuli are used for in vitro studies, the impact of O2 is likely to be linked to TCR signaling modulations. In the case of antitumor immune responses in vivo, tumor antigen-specific T-cell responses (i.e., TCR-dependent) will be the most important to study.

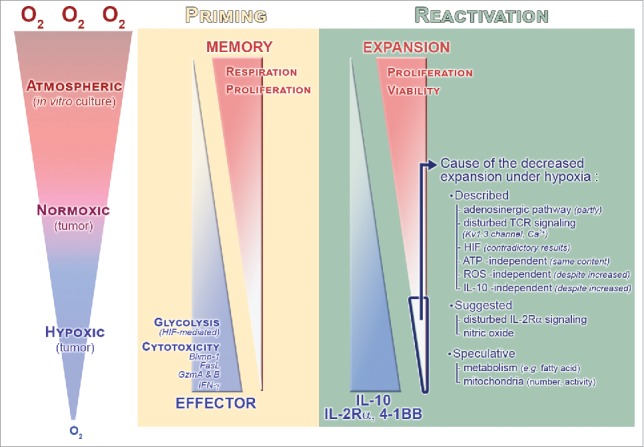

Several studies have shown that T cell priming under low O2 fractions can increase differentiation of CD8+ T cells toward more lytic effector cells, even if these may be fewer in number because of reduced expansion.21,28,42,48 Specifically, granzyme A and B were upregulated when CTLs were generated under physiological normoxia, as were FasL and Blimp-1, with capacity to secrete higher amounts of IFNγ.21,49 The metabolic profile of the cells was also described to switch from an oxidative phosphorylation metabolism toward a more glycolytic one when O2 availability was lowered.38 Indeed, several lines of evidence suggest that the increase in effector differentiation observed under low O2 tensions would be a result of increased glycolysis (usually associated with effector differentiation,30 as opposed to memory differentiation that relies on oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid oxidation), due to increased HIF activity.19,38 Interestingly, the killing capacity of CD8+ T cells previously primed under atmospheric O2 fraction can be enhanced by conditioning them under low O2 fractions for a few days via a mechanism independent of granzyme B induction.21,42 In line with this effector differentiation modulation, it has been shown that HIF activity negatively controls the expression of CD62L and CCR7, but also, intriguingly, of S1P1, CCR5, CXCR3, and CXCR4; these key molecules clearly impact on T cell trafficking, but the capacity of homing to tumor has not been assessed.19

Taken together, these results suggest that CD8+ T cells primed in vivo under physiological normoxia differentiate toward effector cells with higher killing capacities, at the expense of their overall expansion; this is in contrast to conclusions that would be reached if extrapolating from in vitro priming under atmospheric O2 tension. This raises the possibility of exploring the generation of T cells under low O2 fractions for adoptive cell transfer therapy of cancer, even if use of naive T cells would be clinically challenging. Moreover, the advantages of increased effector capacities to kill tumor cells in the short term would have to be balanced against the well-documented advantages of controlling tumor growth in the long term by transfer of less differentiated CD8+ T cells (stem-cell memory and memory stage), with their better persistence and capacity to self-renew.50-52

Hypoxia and reactivation of CD8+ T cells

Once primed, CD8+ T cells differentiate, and a fraction of them (i.e., CTLs) egress from lymphoid organs to enter the tumor site where they will face hypoxia (Fig. 2; example of a brain tumor that often presents hypoxic areas). For antitumor function, it is of critical importance to decipher the impact of hypoxia on the fate and function of these effector cells, including cytolytic capacities, proliferation and survival.

Hypoxia does not impact CTL cytolytic capacities

In vitro, CD8+ T-cell priming under atmospheric oxygen fraction gives rise to higher cytolytic capacities of the resulting CTLs when preconditioned under hypoxia for a few days before the killing assay.21 However, this result can be confusing since it has been shown that hypoxia has no impact on CTL cytolytic capacities when comparing to physiological normoxia,21,48 further emphasizing how important it is to use physiologically relevant oxygen fractions to infer hypoxia impact. Moreover, tumor cell cytolysis mediated by CTLs is, at least, a bipartite integrative response resulting from CTL cytolytic capacities together with tumor susceptibility to cell lysis. Even if hypoxia does not impact directly CTL cytolytic capacities, seminal studies from Chouaib et al. have shown that hypoxia induces resistance of tumor cells to CTL-mediated cytotoxicity, as recently reviewed.12 Indeed, hypoxia promotes autophagy in tumor cells through a mechanism involving STAT3 activation and miR-210 upregulation, leading to selective degradation of granzyme B.53-56 Consequently, in situ hypoxia would inhibit tumor cell cytolysis through its impact on tumor cells rather than on CTLs.

Hypoxia decreases CTL proliferation and viability after reactivation

An important feature of CD8+ T cells is whether they can proliferate after reactivation at the hypoxic tumor site to maintain sufficient numbers to eradicate or control tumor cells. It is now becoming clear that expansion of reactivated CTLs is positively correlated with oxygen levels,21 as previously described for CD8+ T cells during priming. Hypoxia prevents CD8+ T cell expansion by decreasing both cell proliferation rate and viability (at least partly through apoptosis induction). Importantly, T cells left in culture without reactivation are not impacted by hypoxia, thus showing that hypoxia as a detrimental impact on T cells only when combined with activation/TCR signaling.38 Whether longer term persistence of tissue resident memory cells (TRM) under low O2 fractions in vivo would be impacted has yet to be addressed.57-59 The exact mechanisms impacting expansion are still not clear, but several possible mechanisms have been proposed; these are likely to be common to both naive and antigen-experienced T cells. A decrease in ATP levels has been logically envisaged, since cells rely more on glycolysis (which is less efficient at producing energy) than on the impaired oxidative phosphorylation under hypoxia. However, this has been refuted since T cells were able to maintain the same intracellular levels of ATP under hypoxia.36,39,41 Whether HIF-1α stabilization is directly responsible for the decrease in cell expansion is not clear for mature T cells,19,34,60 although in thymocytes it leads to disrupted TCR signal transduction (via an altered Ca2+ response).61 Nonetheless, a hypoxia-induced disturbance in TCR signal transduction might be involved, as TCR-independent stimulation (i.e., PMA and ionomycin) was shown to have no impact on cell proliferation of human PBMCs under hypoxia (as opposed to TCR-dependent stimulation, for which expansion defects were linked to Kv1.3 potassium channels activity and Ca2+ homeostasis).37,62 Interestingly, under hypoxia there is often reduced secretion of IL-2, whereas IL-2Rα is upregulated.21,28,31,39 However, reduced IL-2 secretion may not be a key factor, but rather a result of the decreased cell number, as adding exogenous IL-2 does not reverse the decreased proliferation observed under hypoxia.21,63 Signaling through IL-2Rα may warrant further investigation, since dysregulation was noted under hypoxia, with increased STAT5 phosphorylation.39 Importantly, in vitro generated CTLs and ex vivo CD8+ TILs (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes) reactivated under hypoxia have been shown to produce the cytokine IL-10 (also noted for Th1 CD4+ T cells in an HIF-1α-dependent manner),64 although this autocrine production was not responsible for impaired CD8+ T cells proliferation.21 Intriguingly, IL-10 secretion was also promoted under physiological normoxia, thus implying that IL-10 would be commonly produced by CD8+ T cells in vivo under physiological oxygen fractions. In vivo, adenosine is accumulating in hypoxic areas leading to A2AR-dependent immunosuppression.65 This raises the possibility that the hypoxia-induced decrease in T-cell proliferation would be linked to this pathway, but a recent report suggested that it was mostly A2AR-independent.40 Another possibility that has been explored is the hypoxia-promoted production of ROS,27,39 with important roles in T-cell activation,66,67 and a capacity to stabilize HIFs.68 However, adding the exogenous antioxidant N-acetylcysteine did not show any improvement in T cell proliferation.27 Overall, the decreased T-cell expansion under hypoxia is still not fully elucidated, but is an important issue to address; identification of the pathway involved could provide therapeutic targets of importance for cancer immunotherapy.

A beneficial role of hypoxia for antitumor CTLs?

Recently, two studies challenged the aforementioned paradigm that hypoxia would be a negative regulator of antitumor CD8+ T cells. In an elegant mouse model, Doedens et al. claimed that HIF activity was important for sustained CTL function, either in a chronic infection or in a tumor context.20 However, since VHL-deficient CTLs were utilized, the effect may not be purely HIF dependent. Furthermore, as CTLs generated under low oxygen fractions have increased killing capacities, the observed improvement in CTL activity might have been due to an increase in HIF activity during priming, rather than during the CTL reactivation. Finally, as HIF activity might not be the primary cause of the effect observed under hypoxia, and as it is involved in CD8+ T-cell physiology even in non-hypoxic conditions, we consider that the impact of hypoxia on CTLs should not be inferred only from increased HIF activity without directly studying hypoxic O2 levels. In the second study, Xu et al. compared how different subsets of human CD8+ T cells were impacted by hypoxia.42 Hypoxia negatively impacted proliferation of naive and central memory T cells after activation, whereas, surprisingly, it enhanced effector memory T cell proliferation, through an increased HIF-1α/glycolysis positive loop. This effect was described to be linked to the dual role of GAPDH. Indeed, as glycolysis is more active in effector memory cells, under hypoxia GAPDH becomes devoted to glycolysis at the expense of its HIF-1α translational repressing abilities. Indeed, it makes sense that effector memory cells, which rely on glycolysis rather than on oxidative phosphorylation, would be more adapted to face oxygen deprivation than naive and central memory cells. However, one caveat of this study is that hypoxia impact was compared with atmospheric O2; effector memory cells may have proliferated to the same extent under physiological normoxic oxygen fraction. Nevertheless, these important results warrant further studies and confirmation.

CTLs reactivated under hypoxia show enhanced IL-10, IL-2Rα, and 4-1BB expression

In an effort to recapitulate maximally in vitro what happens in vivo, our group generated CTLs under 5% O2 to mimic priming in secondary lymphoid organs and reactivated them either under 5% O2 or 1% O2 to mimic reactivation in a normoxic or hypoxic tumor, respectively.21 We consider that these culture conditions avoid some experimental artifacts resulting from the dramatic decrease in O2 availability during CTL reactivation (e.g., from 21% to 1%) that would not occur in vivo. Indeed, we observed that as compared to the classical comparison 1% O2 vs 21% O2, comparing 1% O2 vs 5% O2 led to significantly less transcriptional modulation. We suggest that the far greater number of genes that would be differentially transcribed when making a 1% O2 to 21% O2 comparison should be considered as false positives. Using this more physiologically relevant approach, we found that IL-10, IL-2Rα (CD25), and 4-1BB (CD137) were upregulated when cells were reactivated under hypoxia. Upregulation of 4-1BB has already been described in endothelial cells and T cells under hypoxia (via HIF-1α activity) and represents a promising strategy to reinvigorate the immune response to cancer.69-71 Interestingly, we observed that though HIF-1α was not modulated at the RNA level, HIF-2α was upregulated under hypoxia. This result emphasizes that HIF-2α, which has been scarcely studied in T cell reactivated under hypoxia (as opposed to the extensively studied HIF-1α),20 warrants further investigation. Nevertheless, a limitation in our approach is that we analyzed the response of reactivated CTL to relatively chronic hypoxia (i.e., 2–4 d). Indeed, because hypoxia promotes a delay in cell proliferation, long-term analyses of markers and RNA profiling of cells that are not synchronized in their division cycle, and/or that divided differently, might bias the interpretation.

Concluding remarks

Hypoxia studies highlight the critical role of O2 in immune responses and T-cell physiology and allow a more comprehensive view of the most likely functions and fate of T cells in vivo (Fig. 3). However, we propose that a better understanding and consensus of the impact of hypoxia on T cells can be reached if more attention is paid to normoxic/hypoxic terminologies and values, the uncoupling of solely HIF-based results and hypoxia impact, and definition of the stage of T-cell differentiation.

Figure 3.

Direct and specific impact of atmospheric, normoxic, and hypoxic oxygen fractions during CD8+ T-cell priming and reactivation. Oxygen fraction during the priming impacts CD8+ T-cell effector/memory differentiation. Associated parameters are shown in the diagram. Importantly, during reactivation where CD8+ T cells face hypoxia, expansion correlates positively with oxygen levels, whereas it is the opposite trend for IL-10, IL-2Rα, and 4-1BB. The cause of the decreased expansion of CTL reactivated under hypoxia is still not clear: Mechanisms that were previously described or suggested (from studies investigating the hypoxia impact) are shown.

Tumors present a hostile microenvironment for immune cells, with many immunosuppressive features; hypoxia-regulated CTL proliferation and survival is likely to be one of these. One strategy to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy would be to improve tumor oxygenation. To this end, modulating tumor vascularization could represent an attractive approach. In fact, despite the highly vascularized characteristic of tumors, tumor vessels are regularly leaky and malfunctional. Consequently, the use of anti-angiogenic drugs has shown to be useful for vessel normalization but often leads to hypoxia enhancement.72 Development of these approaches considered principally the tumor cell; our current understanding of the importance of antitumor immunity now forces us to also consider the consequences for immune cells.73 Alternatively, Hatfield et al. recently used respiratory hyperoxia (i.e., atmosphere supplemented with O2 up to 60%) in mouse tumor models; this promoted an NK- and T-cell-dependant tumor regression.74 The study reported that hypoxic areas were decreased and CD8+ T-cell infiltration was enhanced (via the hypoxia-adenosine pathway). As CD8+ T cells were less present in hypoxic areas, it was claimed that they avoid hypoxic areas. However, this could also be interpreted as being due to their diminished capacity to expand under hypoxia. Whatever the exact mechanisms involved, these important results corroborate previous findings describing a negative impact of hypoxia on CD8+ T cells in in vitro studies and demonstrate that hypoxia negatively impacts the global antitumor immune response in vivo. This hypoxia impact may also function via other immune cells, which can indirectly affect the antitumor CD8+ T-cell response and the efficacy of current therapeutic treatments.2,4,10-12,14

The success or failure of all cell-based cancer immunotherapies is ultimately determined at the tumor site that is frequently oxygen-deprived. Therefore, reaching a better understanding of the O2-dependence of CD8+ T-cell responses and determining the molecular pathways involved will undoubtedly open new therapeutic opportunities to manipulate T cell metabolism, survival, and antitumor effector function.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported by the “Fondation pour les recherches médico-biologiques” and the “Recherche Suisse contre le cancer.”

References

- 1.Ivanovic Z. Hypoxia or in situ normoxia: The stem cell paradigm. J Cell Physiol 2009; 219:271-5; PMID:19160417; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.21690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNamee EN, Korns Johnson D, Homann D, Clambey ET. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factors as regulators of T cell development, differentiation, and function. Immunol Res 2013; 55:58-70; PMID:22961658; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12026-012-8349-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carreau A, El Hafny-Rahbi B, Matejuk A, Grillon C, Kieda C. Why is the partial oxygen pressure of human tissues a crucial parameter? Small molecules and hypoxia. J Cell Mol Med 2011; 15:1239-53; PMID:21251211; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01258.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:656-65; PMID:21323543; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMra0910283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tatum JL, Kelloff GJ, Gillies RJ, Arbeit JM, Brown JM, Chao KS, Chapman JD, Eckelman WC, Fyles AW, Giaccia AJ et al.. Hypoxia: importance in tumor biology, noninvasive measurement by imaging, and value of its measurement in the management of cancer therapy. Int J Radiat Biol 2006; 82:699-757; PMID:17118889; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/09553000601002324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zagzag D, Zhong H, Scalzitti JM, Laughner E, Simons JW, Semenza GL. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in brain tumors: association with angiogenesis, invasion, and progression. Cancer 2000; 88:2606-18; PMID:10861440; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/1097-0142(20000601)88:11%3c2606::AID-CNCR25%3e3.0.CO;2-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholz CC, Taylor CT. Targeting the HIF pathway in inflammation and immunity. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2013; 13:646-53; PMID:23660374; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coph.2013.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Z, Bao S, Wu Q, Wang H, Eyler C, Sathornsumetee S, Shi Q, Cao Y, Lathia J, McLendon RE et al.. Hypoxia-inducible factors regulate tumorigenic capacity of glioma stem cells. Cancer Cell 2009; 15:501-13; PMID:19477429; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris AL. Hypoxia–a key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat Rev Cancer 2002; 2:38-47; PMID:11902584; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semenza GL. Defining the role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in cancer biology and therapeutics. Oncogene 2010; 29:625-34; PMID:19946328; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2009.441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noman MZ, Hasmim M, Messai Y, Terry S, Kieda C, Janji B, Chouaib S. Hypoxia: a key player in antitumor immune response. A review in the theme: Cellular responses to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2015; 309:C569-79; PMID:26310815; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajpcell.00207.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chouaib S, Noman MZ, Kosmatopoulos K, Curran MA. Hypoxic stress: obstacles and opportunities for innovative immunotherapy of cancer. Oncogene 2016; PMID:27345407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2016.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar V, Gabrilovich DI. Hypoxia-inducible factors in regulation of immune responses in tumour microenvironment. Immunology 2014; 143:512-9; PMID:25196648; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/imm.12380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winning S, Fandrey J. Dendritic cells under hypoxia: How oxygen shortage affects the linkage between innate and adaptive immunity. J Immunol Res 2016; 2016:5134329; PMID:26966693; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1155/2016/5134329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, Jinasena D, Yu H, Zheng Y, Bordman Z, Fu J, Kim Y, Yen HR et al.. Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell 2011; 146:772-84; PMID:21871655; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2003; 3:721-32; PMID:13130303; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lolkema MP, Gervais ML, Snijckers CM, Hill RP, Giles RH, Voest EE, Ohh M. Tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein requires phosphorylation of the acidic domain. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:22205-11; PMID:15824109; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M503220200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cummins EP, Berra E, Comerford KM, Ginouves A, Fitzgerald KT, Seeballuck F, Godson C, Nielsen JE, Moynagh P, Pouyssegur J et al.. Prolyl hydroxylase-1 negatively regulates IkappaB kinase-beta, giving insight into hypoxia-induced NFkappaB activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:18154-9; PMID:17114296; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0602235103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finlay DK, Rosenzweig E, Sinclair LV, Feijoo-Carnero C, Hukelmann JL, Rolf J, Panteleyev AA, Okkenhaug K, Cantrell DA. PDK1 regulation of mTOR and hypoxia-inducible factor 1 integrate metabolism and migration of CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med 2012; 209:2441-53; PMID:23183047; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20112607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doedens AL, Phan AT, Stradner MH, Fujimoto JK, Nguyen JV, Yang E, Johnson RS, Goldrath AW. Hypoxia-inducible factors enhance the effector responses of CD8(+) T cells to persistent antigen. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:1173-82; PMID:24076634; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ni.2714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vuillefroy de Silly R, Ducimetiere L, Yacoub Maroun C, Dietrich PY, Derouazi M, Walker PR. Phenotypic switch of CD8(+) T cells reactivated under hypoxia toward IL-10 secreting, poorly proliferative effector cells. Eur J Immunol 2015; 45:2263-75; PMID:25929785; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/eji.201445284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang CH, Curtis JD, Maggi LB Jr., Faubert B, Villarino AV, O'Sullivan D, Huang SC, van der Windt GJ, Blagih J, Qiu J et al.. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell 2013; 153:1239-51; PMID:23746840; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zumwalde NA, Domae E, Mescher MF, Shimizu Y. ICAM-1-dependent homotypic aggregates regulate CD8 T cell effector function and differentiation during T cell activation. J Immunol 2013; 191:3681-93; PMID:23997225; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1201954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arsham AM, Howell JJ, Simon MC. A novel hypoxia-inducible factor-independent hypoxic response regulating mammalian target of rapamycin and its targets. J Biol Chem 2003; 278:29655-60; PMID:12777372; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M212770200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park EC, Ghose P, Shao Z, Ye Q, Kang L, Xu XZ, Powell-Coffman JA, Rongo C. Hypoxia regulates glutamate receptor trafficking through an HIF-independent mechanism. EMBO J 2012; 31:1379-93; PMID:22252129; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2011.499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atkuri KR, Herzenberg LA. Culturing at atmospheric oxygen levels impacts lymphocyte function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:3756-9; PMID:15738407; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0409910102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Atkuri KR, Herzenberg LA, Niemi AK, Cowan T. Importance of culturing primary lymphocytes at physiological oxygen levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104:4547-52; PMID:17360561; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0611732104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caldwell CC, Kojima H, Lukashev D, Armstrong J, Farber M, Apasov SG, Sitkovsky MV. Differential effects of physiologically relevant hypoxic conditions on T lymphocyte development and effector functions. J Immunol 2001; 167:6140-9; PMID:11714773; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dutton RW, Bradley LM, Swain SL. T cell memory. Annu Rev Immunol 1998; 16:201-23; PMID:9597129; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buck MD, O'Sullivan D, Pearce EL. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J Exp Med 2015; 212:1345-60; PMID:26261266; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20151159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuckerberg AL, Goldberg LI, Lederman HM. Effects of hypoxia on interleukin-2 mRNA expression by T lymphocytes. Crit Care Med 1994; 22:197-203; PMID:8306676; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/00003246-199402000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krieger JA, Landsiedel JC, Lawrence DA. Differential in vitro effects of physiological and atmospheric oxygen tension on normal human peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferation, cytokine and immunoglobulin production. Int J Immunopharmacol 1996; 18:545-52; PMID:9080248; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0192-0561(96)00057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naldini A, Carraro F, Silvestri S, Bocci V. Hypoxia affects cytokine production and proliferative responses by human peripheral mononuclear cells. J Cell Physiol 1997; 173:335-42; PMID:9369946; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199712)173:3%3c335::AID-JCP5%3e3.0.CO;2-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makino Y, Nakamura H, Ikeda E, Ohnuma K, Yamauchi K, Yabe Y, Poellinger L, Okada Y, Morimoto C, Tanaka H. Hypoxia-inducible factor regulates survival of antigen receptor-driven T cells. J Immunol 2003; 171:6534-40; PMID:14662854; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roman J, Rangasamy T, Guo J, Sugunan S, Meednu N, Packirisamy G, Shimoda LA, Golding A, Semenza G, Georas SN. T-cell activation under hypoxic conditions enhances IFN-gamma secretion. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2010; 42:123-8; PMID:19372249; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0139OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dziurla R, Gaber T, Fangradt M, Hahne M, Tripmacher R, Kolar P, Spies CM, Burmester GR, Buttgereit F. Effects of hypoxia and/or lack of glucose on cellular energy metabolism and cytokine production in stimulated human CD4+ T lymphocytes. Immunol Lett 2010; 131:97-105; PMID:20206208; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conforti L, Petrovic M, Mohammad D, Lee S, Ma Q, Barone S, Filipovich AH. Hypoxia regulates expression and activity of Kv1.3 channels in T lymphocytes: a possible role in T cell proliferation. J Immunol 2003; 170:695-702; PMID:12517930; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larbi A, Zelba H, Goldeck D, Pawelec G. Induction of HIF-1alpha and the glycolytic pathway alters apoptotic and differentiation profiles of activated human T cells. J Leukoc Biol 2010; 87:265-73; PMID:19892848; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1189/jlb.0509304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gaber T, Tran CL, Schellmann S, Hahne M, Strehl C, Hoff P, Radbruch A, Burmester GR, Buttgereit F. Pathophysiological hypoxia affects the redox state and IL-2 signalling of human CD4+ T cells and concomitantly impairs survival and proliferation. Eur J Immunol 2013; 43:1588-97; PMID:23519896; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/eji.201242754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohta A, Madasu M, Subramanian M, Kini R, Jones G, Chouker A, Sitkovsky M. Hypoxia-induced and A2A adenosine receptor-independent T-cell suppression is short lived and easily reversible. Int Immunol 2014; 26:83-91; PMID:24150242; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/intimm/dxt045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dimeloe S, Mehling M, Frick C, Loeliger J, Bantug GR, Sauder U, Fischer M, Belle R, Develioglu L, Tay S et al.. The immune-metabolic basis of effector memory CD4+ T cell function under hypoxic conditions. J Immunol 2016; 196:106-14; PMID:26621861; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1501766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu Y, Chaudhury A, Zhang M, Savoldo B, Metelitsa LS, Rodgers J, Yustein JT, Neilson JR, Dotti G. Glycolysis determines dichotomous regulation of T cell subsets in hypoxia. J Clin Invest 2016; 126(7):2678-2688; PMID:27294526; http://dx.doi.org/17015677 10.1172/JCI85834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukashev D, Klebanov B, Kojima H, Grinberg A, Ohta A, Berenfeld L, Wenger RH, Sitkovsky M. Cutting edge: hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and its activation-inducible short isoform I.1 negatively regulate functions of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol 2006; 177:4962-5; PMID:17015677; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.4962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lukashev D, Sitkovsky M. Preferential expression of the novel alternative isoform I.3 of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha in activated human T lymphocytes. Human immunology 2008; 69:421-5; PMID:18638657; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holmquist-Mengelbier L, Fredlund E, Lofstedt T, Noguera R, Navarro S, Nilsson H, Pietras A, Vallon-Christersson J, Borg A, Gradin K et al.. Recruitment of HIF-1alpha and HIF-2alpha to common target genes is differentially regulated in neuroblastoma: HIF-2alpha promotes an aggressive phenotype. Cancer Cell 2006; 10:413-23; PMID:17097563; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC. HIF1alpha and HIF2alpha: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12:9-22; PMID:22169972; http://dx.doi.org/23563312 10.1038/nrc3183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanna SC, Krishnan B, Bailey ST, Moschos SJ, Kuan PF, Shimamura T, Osborne LD, Siegel MB, Duncan LM, O'Brien ET 3rd et al.. HIF1alpha and HIF2alpha independently activate SRC to promote melanoma metastases. J Clin Invest 2013; 123:2078-93; PMID:23563312; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI66715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakagawa Y, Negishi Y, Shimizu M, Takahashi M, Ichikawa M, Takahashi H. Effects of extracellular pH and hypoxia on the function and development of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunol Lett 2015; 167:72-86; PMID:26209187; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haddad H, Windgassen D, Ramsborg CG, Paredes CJ, Papoutsakis ET. Molecular understanding of oxygen-tension and patient-variability effects on ex vivo expanded T cells. Biotechnol Bioeng 2004; 87:437-50; PMID:15286980; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bit.20166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Palmer DC, Wrzesinski C, Kerstann K, Yu Z, Finkelstein SE, Theoret MR, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest 2005; 115:1616-26; PMID:15931392; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI24480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gattinoni L, Lugli E, Ji Y, Pos Z, Paulos CM, Quigley MF, Almeida JR, Gostick E, Yu Z, Carpenito C et al.. A human memory T cell subset with stem cell-like properties. Nat Med 2011; 17:1290-7; PMID:21926977; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.2446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sukumar M, Liu J, Mehta GU, Patel SJ, Roychoudhuri R, Crompton JG, Klebanoff CA, Ji Y, Li P, Yu Z et al.. Mitochondrial membrane potential identifies cells with enhanced stemness for cellular therapy. Cell Metabolism 2016; 23:63-76; PMID:26674251; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Noman MZ, Buart S, Van Pelt J, Richon C, Hasmim M, Leleu N, Suchorska WM, Jalil A, Lecluse Y, El Hage F et al.. The cooperative induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha and STAT3 during hypoxia induced an impairment of tumor susceptibility to CTL-mediated cell lysis. J Immunol 2009; 182:3510-21; PMID:19265129; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.0800854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noman MZ, Janji B, Kaminska B, Van Moer K, Pierson S, Przanowski P, Buart S, Berchem G, Romero P, Mami-Chouaib F et al.. Blocking hypoxia-induced autophagy in tumors restores cytotoxic T-cell activity and promotes regression. Cancer Res 2011; 71:5976-86; PMID:21810913; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noman MZ, Buart S, Romero P, Ketari S, Janji B, Mari B, Mami-Chouaib F, Chouaib S. Hypoxia-inducible miR-210 regulates the susceptibility of tumor cells to lysis by cytotoxic T cells. Cancer Res 2012; 72:4629-41; PMID:22962263; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baginska J, Viry E, Berchem G, Poli A, Noman MZ, van Moer K, Medves S, Zimmer J, Oudin A, Niclou SP et al.. Granzyme B degradation by autophagy decreases tumor cell susceptibility to natural killer-mediated lysis under hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:17450-5; PMID:24101526; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1304790110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Masson F, Calzascia T, Di Berardino-Besson W, de Tribolet N, Dietrich PY, Walker PR. Brain microenvironment promotes the final functional maturation of tumor-specific effector CD8+ T cells. J Immunol 2007; 179:845-53; PMID:17617575; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Djenidi F, Adam J, Goubar A, Durgeau A, Meurice G, de Montpreville V, Validire P, Besse B, Mami-Chouaib F. CD8+CD103+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are tumor-specific tissue-resident memory T cells and a prognostic factor for survival in lung cancer patients. J Immunol 2015; 194:3475-86; PMID:25725111; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1402711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steinbach K, Vincenti I, Kreutzfeldt M, Page N, Muschaweckh A, Wagner I, Drexler I, Pinschewer D, Korn T, Merkler D. Brain-resident memory T cells represent an autonomous cytotoxic barrier to viral infection. J Exp Med 2016; PMID:27377586; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1084/jem.20151916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thiel M, Caldwell CC, Kreth S, Kuboki S, Chen P, Smith P, Ohta A, Lentsch AB, Lukashev D, Sitkovsky MV. Targeted deletion of HIF-1alpha gene in T cells prevents their inhibition in hypoxic inflamed tissues and improves septic mice survival. PLoS One 2007; 2:e853; PMID:17786224; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0000853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neumann AK, Yang J, Biju MP, Joseph SK, Johnson RS, Haase VH, Freedman BD, Turka LA. Hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha regulates T cell receptor signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102:17071-6; PMID:16286658; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0506070102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Robbins JR, Lee SM, Filipovich AH, Szigligeti P, Neumeier L, Petrovic M, Conforti L. Hypoxia modulates early events in T cell receptor-mediated activation in human T lymphocytes via Kv1.3 channels. J Physiol 2005; 564:131-43; PMID:15677684; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.081893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Clambey ET, McNamee EN, Westrich JA, Glover LE, Campbell EL, Jedlicka P, de Zoeten EF, Cambier JC, Stenmark KR, Colgan SP et al.. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha-dependent induction of FoxP3 drives regulatory T-cell abundance and function during inflammatory hypoxia of the mucosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109:E2784-93; PMID:22988108; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1202366109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shehade H, Acolty V, Moser M, Oldenhove G. Cutting edge: Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 negatively regulates Th1 function. J Immunol 2015; 195:1372-6; PMID:26179900; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.1402552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sitkovsky MV, Lukashev D, Apasov S, Kojima H, Koshiba M, Caldwell C, Ohta A, Thiel M. Physiological control of immune response and inflammatory tissue damage by hypoxia-inducible factors and adenosine A2A receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 2004; 22:657-82; PMID:15032592; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sena LA, Li S, Jairaman A, Prakriya M, Ezponda T, Hildeman DA, Wang CR, Schumacker PT, Licht JD, Perlman H et al.. Mitochondria are required for antigen-specific T cell activation through reactive oxygen species signaling. Immunity 2013; 38:225-36; PMID:23415911; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kesarwani P, Murali AK, Al-Khami AA, Mehrotra S. Redox regulation of T-cell function: from molecular mechanisms to significance in human health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013; 18:1497-534; PMID:22938635; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/ars.2011.4073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bell EL, Klimova TA, Eisenbart J, Moraes CT, Murphy MP, Budinger GR, Chandel NS. The Qo site of the mitochondrial complex III is required for the transduction of hypoxic signaling via reactive oxygen species production. J Cell Biol 2007; 177:1029-36; PMID:17562787; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200609074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Palazon A, Teijeira A, Martinez-Forero I, Hervas-Stubbs S, Roncal C, Penuelas I, Dubrot J, Morales-Kastresana A, Perez-Gracia JL, Ochoa MC et al.. Agonist anti-CD137 mAb act on tumor endothelial cells to enhance recruitment of activated T lymphocytes. Cancer Res 2011; 71:801-11; PMID:21266358; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palazon A, Martinez-Forero I, Teijeira A, Morales-Kastresana A, Alfaro C, Sanmamed MF, Perez-Gracia JL, Penuelas I, Hervas-Stubbs S, Rouzaut A et al.. The HIF-1alpha hypoxia response in tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes induces functional CD137 (4-1BB) for immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 2012; 2:608-23; PMID:22719018; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yonezawa A, Dutt S, Chester C, Kim J, Kohrt HE. Boosting Cancer Immunotherapy with anti-CD137 Antibody Therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2015; 21:3113-20; PMID:25908780; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McIntyre A, Harris AL. Metabolic and hypoxic adaptation to anti-angiogenic therapy: a target for induced essentiality. EMBO Mol Med 2015; 7:368-79; PMID:25700172; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.15252/emmm.201404271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vanneman M, Dranoff G. Combining immunotherapy and targeted therapies in cancer treatment. Nat Rev Cancer 2012; 12:237-51; PMID:22437869; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nrc3237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hatfield SM, Kjaergaard J, Lukashev D, Schreiber TH, Belikoff B, Abbott R, Sethumadhavan S, Philbrook P, Ko K, Cannici R et al.. Immunological mechanisms of the antitumor effects of supplemental oxygenation. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7:277ra30; PMID:25739764; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]