Abstract

This study compares trends in work-family context by education level from 1976 to 2011 among U.S. women. The major aim is to assess whether differences in work-family context by education level widened, narrowed, or persisted. We used data from the 1976–2011 March Current Population Surveys on women aged 25–64 (n=1,597,914). We compare trends in four work-family forms by education level within three race/ethnic groups. The work-family forms reflect combinations of marital and employment status among women with children at home. Trends in the four work-family forms exhibited substantial heterogeneity by education and race/ethnicity. Educational differences in the work-family forms widened mainly among white women. Compared with more-educated peers, white women without a high school credential became increasingly less likely to be married, to be employed, to have children at home, and to combine these roles. In contrast, educational differences in the work-family forms generally narrowed among black women and were directionally mixed among Hispanic women. Only one form—unmarried and employed with children at home—became more strongly linked to a woman’s education level within all three race/ethnic groups. This form carries an elevated risk of work-family conflict and its prevalence increased moderately during the 35-year period. Taken together, the trends underscore recent calls to elevate work-family policy on the national agenda.

Keywords: education, women, work-family context, work-family conflict

This study provides a detailed assessment of trends in work-family context by education level from 1976 to 2011 among U.S. women. Although overarching trends in work and family in post-WWII America are well-documented, this study contributes to the literature by investigating: (1) temporal trends in how women combine work and family—that is, work-family context—by education level within three race/ethnic groups, and (2) whether differences in work-family context across education levels widened, narrowed, or persisted during the 35-year period.

We also discuss the potential implications of these demographic trends on work-family conflict, a topic that is important and timely. The challenges of combining paid work and family in contemporary America have been recently spotlighted in the media (Coontz 2013; Sandberg 2013; Slaughter 2012). The attention partly reflects mounting evidence that work-family conflict has increased (Nomaguchi 2009; Winslow 2005) and the fact that 2013 marks both the 50th anniversary of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963)—which helped launch women’s movement into the paid labor force—and the 20th anniversary of the Family and Medical Leave Act, which was intended to alleviate specific episodes of work-family conflict. This study reveals stark differences in how work-family context has changed for women with differing levels of education, and which subgroups of women may consequently bear a disproportionate risk of work-family conflict. The results will also be valuable for designing studies to assess the extent to which the trends help explain growing disparities in women’s health and longevity.

Background

Disparities in several indicators of U.S. women’s health and longevity, such as self-rated health and total and active life expectancy, have widened across education levels in recent decades (Crimmins and Saito 2001; Goesling 2007; Montez et al. 2011; Olshansky et al. 2012). The reasons for the widening disparities remain poorly understood. Studies investigating the reasons have largely focused on behavioral explanations, such as differential trends in smoking and obesity (e.g., Cutler et al. 2010). However, a complete explanation must incorporate contextual factors that are the social and economic drivers of behaviors, health, and longevity (Berkman and O’Donnell 2013; Montez and Zajacova 2013b; National Research Council 2011).

Trends in work-family context—the combination of employment, marital, and parental roles—are a potentially important contextual explanation for the growing disparities in women’s health and longevity. To start, work-family context is a strong predictor of health and longevity (Barnett and Hyde 2001; Crosby 1991; Frech and Damaske 2012; Martikainen 1995; Moen, Dempster-McClain, and Williams 1992; Repetti, Matthews, and Waldron 1989; Thoits 1986; Verbrugge 1983; Waldron, Weiss, and Hughes 1998). Moreover, work-family context changed dramatically in post-WWII America. Women’s labor force participation rates increased sharply, age at first marriage rose, divorce rates increased, the proportion of nonmarital births rose, and single mother households became more common, while fertility rates changed little (Berkman and O’Donnell 2013; Blau 1998; Cherlin 2010; Raley and Bumpass 2003; Spain and Bianchi 1996; Zeng et al. 2012). In addition, as we describe below, work and family life is strongly patterned by education level and this pattern may have changed in recent decades. Finally, few social protection policies, such as universal childcare and paid family leave, to help Americans contend with these demographic changes have been implemented. Thus, many women have been confronted with higher demands from combining employment and parenthood alongside few and shrinking sources of support (e.g., spouse, social protection policies).

Work-Family Context by Education Level and Race/ethnicity

Many aspects of work and family are strongly patterned by socioeconomic status (SES). In this study, we focus on a key dimension of SES, educational attainment. Education is causally and temporally prior to other dimensions of SES, such as income and occupation; it is more stable over the adult life course than other dimensions; and data on education are available for adults regardless of employment status. Furthermore, the time spent acquiring education has implications for the timing of family formation and labor force entry.

Compared to women with fewer years of educational attainment, women with more years of educational attainment are more likely to be married, to be employed full-time, and if raising children, to be doing so in a two-parent household (Blau 1998). Many recent trends in work and family have occurred unevenly by education level. For instance, since the 1960s women without a high school credential have become by far the least likely women to be married (Fry and Cohn 2010). They also experienced the smallest declines in fertility (Rindfuss, Morgan, and Offutt 1996) and largest growth in single-parent households (Blau 1998; Ellwood and Jencks 2004; McLanahan 2004). When employed, they are increasingly likely to have low-wage jobs with little flexibility to manage family demands (Heymann 2000). These women have made few gains into the full-time labor market. The dramatic increase in women’s labor force participation was mainly driven by more-educated women (Spain and Bianchi 1996). While it is well-established that recent trends in work and family have occurred unevenly by education level, it is less clear how trends in work-family context have occurred by education level.

When examining trends in work-family life by education level, it is important to do so within the context of race/ethnicity. It is important first and foremost because these two social factors are highly correlated in the United States. In 1994 (our study’s midpoint), 15% of non-Hispanic white women aged 25 years and older had not graduated high school compared with 26% of black women and 47% of Hispanic women (U.S. Census Bureau n.d.). Thus, stratifying the trends in work-family context by race/ethnicity helps decouple any effects of education from race/ethnicity on the trends. Another reason to stratify the trends by race/ethnicity is that education may have differential consequences for work-family context across race/ethnic groups. Indeed, intersectionality theory (e.g., Jackson and Williams 2006) and empirical evidence implies such a differential. For instance, in 1970 education was a strong predictor of marriage among black women but not among women overall (Fry and Cohn 2010). As another example, a college degree has become a stronger predictor of transitioning to marriage after a nonmarital birth among black women than among white women (Gibson-Davis 2011).

It is also informative to stratify the trends by race/ethnicity because work-family context tends to differ across race/ethnicity due to social, economic, and cultural factors. For example, comparatively low marriage rates among black women partly reflect the disadvantaged economic circumstances of black men (Lichter et al. 1992; Wilson 2012), while comparatively high rates of fertility and married households among Hispanic women may reflect a higher degree of familism (Landale, Oropesa, and Bradatan 2006). The ways in which women combine work, family, and parenthood also vary by race/ethnicity (McLanahan and Casper 1995).

Work-Family Conflict

One consequence of the post-WWII changes in work-family context within the U.S. policy environment is an elevated risk of conflicting demands from paid work and family. Some women have responded to these pressures by reducing their work hours or exiting the labor force (Gornick and Meyers 2005; Williams 2001). This tradeoff has myriad consequences including lower incomes for women and their families. Other women continue to combine these roles, but may experience high levels of role strain as a result.

Work-family conflict appears to have increased in recent decades. Nomaguchi (2009) found a significant increase between 1977 and 1997 in work-family conflict among employed parents. Another study found that the largest increases in work-family conflict were among unmarried, working mothers: in 1977 10% reported that their job and family life interfered with each other a lot versus 21% in 1997 (Winslow 2005). Despite increases in employment, women are more likely than men to be primary caregivers for children and aging parents, and more likely to be employed in low-wage, inflexible jobs. Indeed, a meta-analysis concluded that mothers were more likely than fathers to report work-family conflict (Byron 2005).

The ramifications of work-family conflict are an important economic and public health issue. Williams and Boushey (2010) contend that it has both macroeconomic consequences (e.g., by pushing workers out of the labor force) and microeconomic consequences (e.g., through attrition and lower productivity). In addition, mounting evidence indicates that sustained work-family conflict can damage health. It has been linked with poor health through coping behaviors such as smoking, drinking, and weight gain (Allen and Armstrong 2006; Frone, Barnes, and Farrell 1994; Roos, Lahelma, and Rahkonen 2006), cardiovascular disease risk (Berkman et al. 2010), depressive symptoms (Ertel, Koenen, and Berkman 2008; Frone 2000), sickness absence (Jansen et al. 2006; Väänänen et al. 2008), and overall health (Frone, Russel, and Cooper 1997).

Aims of this Study

Although overarching trends in work and family are well-documented (e.g., Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie 2007; Goldin 2004; Spain and Bianchi 1996), trends by education level have been documented only in broad strokes (great exceptions include Blau 1998; Isen and Stevenson 2010; Martin 2006, 2004; Raley and Bumpass 2003), and trends by education level within race/ethnicity have received scant attention. As we explained above, it is important to assess the trends jointly by education and race/ethnicity. In addition, because work-family context strongly predicts work-family conflict (Winslow 2005), our study responds to a recent review that identified a need to assess the relationship between social class and work-family conflict (Bianchi and Milkie 2010). Filling these gaps is crucial for fully understanding the trends in work-family context and their ramifications for women’s health and longevity.

This study begins to address these gaps by providing a detailed investigation of trends in work-family context by education level among women overall and within three race/ethnic groups. The central questions guiding this study are: To what extent have overarching trends in work-family context occurred across education levels? Have differences in work-family context by education level widened, narrowed, or persisted? Which subgroups experienced the most profound changes in work-family context? Were the changes gradual or discontinuous? While some of these questions have been addressed separately in prior studies, we address them collectively in a single study for three race/ethnic groups using the most recent data.

After addressing our central questions, we discuss the potential implications of our results for work-family conflict. The implications are “potential” because we do not directly measure work-family conflict. Rather, we rely on prior studies documenting that women’s combined employment, marital, and parental roles strongly predict their self-reported level of work-family conflict, and that being unmarried and employed with children under 18 at home carries a particularly high risk of conflict (Bianchi et al. 2007; Winslow 2005).

Data and Methods

Data

We used data from the 1976–2011 March Current Population Surveys (CPS) downloaded from the Minnesota Population Center (2012). The CPS is a monthly household survey of labor market and demographic information. It is nationally-representative of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population 16 years of age and older (U.S. Census Bureau 2006). Households are interviewed monthly for four consecutive months, then again during the same four months one year later. Each March the survey is augmented with additional households and interview questions.

We include all women aged 25–64 years at the time of their March interview to capture the ages at which women were likely to be in the labor force and raising children.1 Setting the lower limit at age 25 also helps ensure that most women had completed their education, at least through a bachelor’s degree. We include all women regardless of race/ethnicity or nativity.

Work, Family, and Work-Family Context

The three work and family characteristics include marital status, employment status, and children in the household. All measures reflect the respondents’ status at the time of interview; therefore, they represent current work-family context, not work-family history. We include binary measures of each characteristic. While more refined measures would paint a detailed portrait of work-family life, the number of work-family forms quickly expands and contains many that are rare and obscure trends in more common forms. Legal marital status was dichotomized into married or unmarried. For consistency across time, the unmarried category includes cohabiting unions because we did not have direct information on cohabitation until 1995.2 Employment status during the preceding week was dichotomized into full-time (35 or more hours per week) versus all other statuses (part-time, unemployed, not in labor force). When data on work hours during the preceding week were unavailable, we used usual work hours during the prior year. We distinguished full-time employment because it reflects a strong attachment to the labor force and the associated time demands. We also included a binary indicator of whether the respondent had at least one child under 18 years of age living in the household. In ancillary analyses we found that using an indicator of two or more children in the household produced similar trends.

The three work and family characteristics were then combined to create eight exhaustive work-family forms. We focus on trends in the four forms that include children at home because these women are most at risk for experiencing work-family conflict (Bianchi and Milkie 2010; Winslow 2005). We refer to these forms as married/not-employed, married/employed, unmarried/not-employed, and unmarried/employed. Trends in the four forms without children at home are available in the online supplement.

Educational Attainment

We used educational attainment to reflect the socioeconomic environment. We assess four education categories: 0–11 years (hereafter “low-educated”); a high school credential (HS); some college; a bachelor’s degree or higher (hereafter “college-educated”).

Race/ethnicity

The CPS collects self-reported information on race and Hispanic ethnicity. The most consistent response categories for race during our study period were white, black, and other. Thus, in addition to trends among women of any race/ethnicity, we also assess trends for non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic women.

Sample Exclusions

Among women aged 25–64 years at interview, we had complete data on age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and children in the household. We excluded 1,705 observations (0.1% of sample) missing information on work hours. We exclude survey years before 1976 when questions about children in the household were not asked in a consistent manner. The final sample contains 1,597,914 observations (71% non-Hispanic white, 11% non-Hispanic black, 12% Hispanic, 6% other).3

Age-Standardized Trends over Time

The prevalence of each work-family characteristic for a given year (or two years) is standardized to the age distribution of the 2011 population within each education stratum. Standardization is critical because the age distribution within education levels has changed over time. To smooth the trends for black and Hispanic women, we estimate prevalence for two-year intervals. All analyses were weighted using the CPS sample weights and conducted with SAS version 9.3.

Results

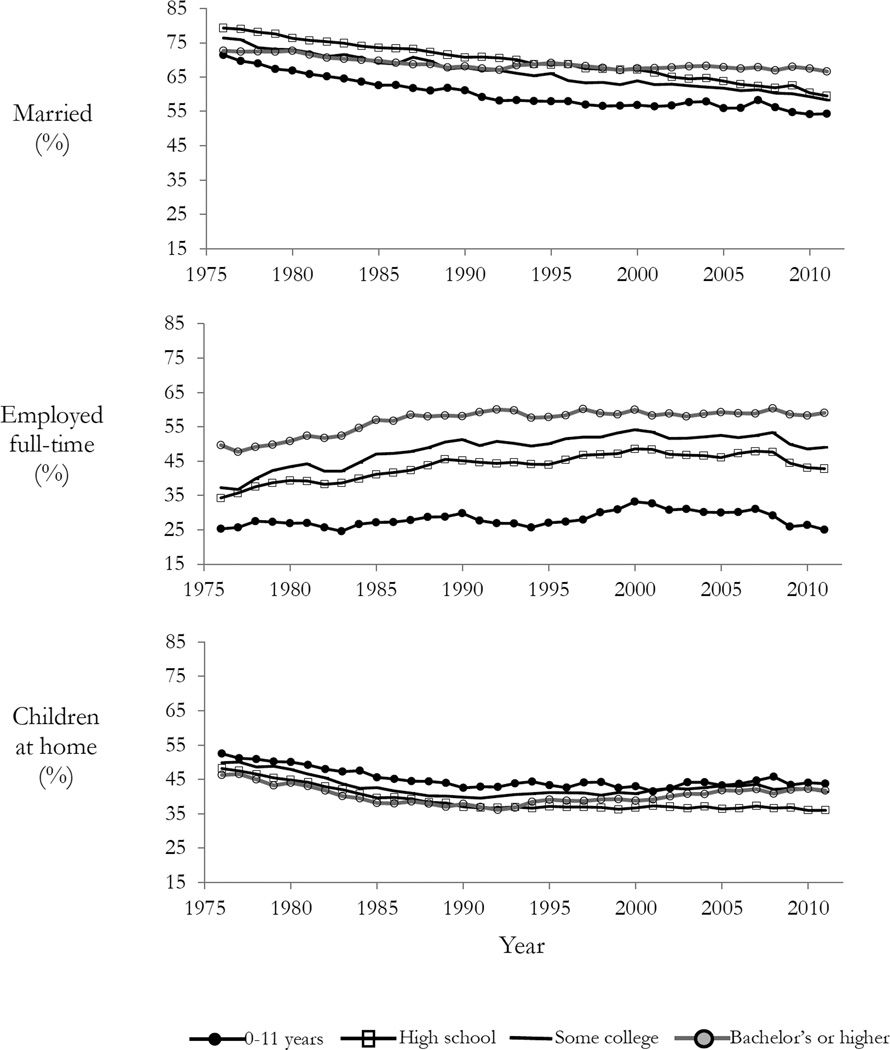

Before examining trends in work-family context, we review trends in the three work and family characteristics. Figure 1 displays trends from 1976 to 2011 in marriage, full-time employment, and children at home by education level for women of any race/ethnicity.

Fig. 1.

Trends in marriage, full-time employment, and children at home by education among women aged 25–64

Marriage

Low-educated women were the least likely group to be married throughout the 35-year period and this difference grew over time. Declines in marriage occurred across all education levels but were relatively shallow among college-educated women, creating a strong educational gradient in marriage by the late 1990s. In 2011 54.3% of low-educated women were married compared with 66.6% of college-educated women, a gap of 12.3%. The marriage gap between these two education levels was just 1.2% in 1976.

Full-time Employment

Low-educated women made few gains into the full-time labor force. Between 1976 and 2011, full-time employment remained fairly stable among the low-educated (from 25.3% to 25.1%) but rose from 49.7% to 59.0% among the college-educated. Increases in employment leveled off in the early 1990s for the college-educated and roughly a decade later for women with a HS credential or some college. Among the three work and family characteristics, the educational gradient in employment was largest and widened the most.

Children Under 18 at Home

Low-educated women were the most likely group to have children at home throughout the study period (analyses below will reveal that this reflects a high proportion of Hispanic women with low education). Educational variation in having children at home was smaller than educational variation in marriage and employment, and it changed little during the 35-year period. The decline in the prevalence of children at home slowed for all women in the early 1990s and gradually reversed for the college-educated.

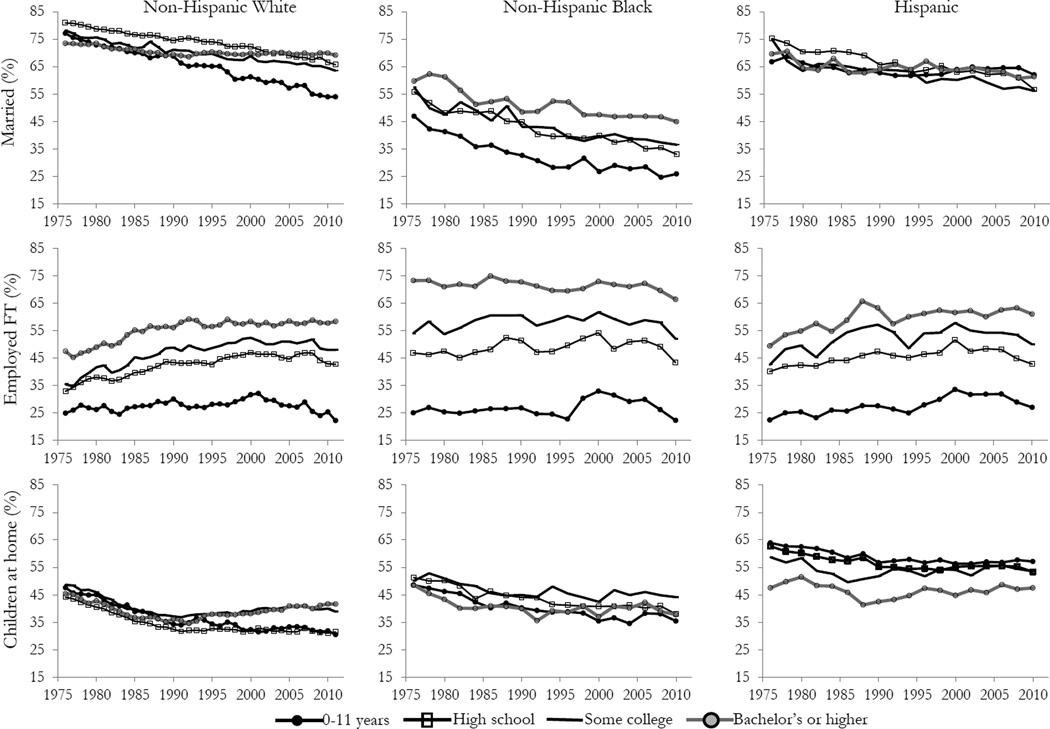

Trends by Race/ethnicity

Figure 2 shows trends in marriage, full-time employment, and children at home by race/ethnicity. To test whether differences across education levels in the prevalence of these roles widened, narrowed, or persisted, we estimated OLS models in Table 1 where×= year and y = the annual difference in the prevalence of a role between college-educated and low-educated women. Among white women the differences between the college-educated and low-educated in the prevalence of marriage, employment, and children at home widened significantly (p<0.001). They widened largely because low-educated white women were increasingly less likely to engage in these roles compared with their better-educated peers. Among black women, the educational gradient in marriage changed little (p<0.10) because marriage declined similarly across education levels. The educational gradient in employment narrowed (p<0.001) mainly because employment declined among the college-educated while holding steady or rising for other education levels. The association between education and children is more complex. Before the early 1980s low-educated black women were marginally more likely to have children at home than their college-educated peers but afterwards this difference reversed. Among Hispanic women, educational differences in marriage (p>0.10) and employment (p>0.10) changed little because declines in marriage and increases in employment were similar across education levels; while the educational gradient in having children at home narrowed (p<0.001).

Fig. 2.

Trends in marriage, full-time (FT) employment, and children at home by education and race/ethnicity among women aged 25–64

Table 1.

OLS regression coefficients predicting the annual difference across education levels in the prevalence of work, family, and work-family forms among women aged 25–64 years, 1976 to 2011a

| Work-family forms with children at home | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Employed full-time |

Children at home |

Married and not employed full-time |

Married and employed full-time |

Unmarried and not employed full-time |

Unmarried and employed full-timeb |

|

| White women | |||||||

| Intercept | −3.97*** | 22.54*** | −4.32*** | −3.91*** | 3.21*** | −4.09*** | −0.61*** |

| Year | 0.53*** | 0.30*** | 0.40*** | 0.26*** | 0.26*** | −0.09*** | −0.05*** |

| R2 | 0.95 | 0.62 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.65 | 0.51 |

| Black women | |||||||

| Intercept | 16.79*** | 47.92*** | −3.13*** | −6.54*** | 19.93*** | −18.35*** | −5.58*** |

| Year | 0.10† | −0.19*** | 0.19*** | 0.27*** | −0.21*** | 0.08* | −0.06* |

| R2 | 0.11 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| Hispanic women | |||||||

| Intercept | 1.87* | 31.01*** | −14.88*** | −10.76*** | 6.46*** | −11.62*** | −1.27** |

| Year | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.15*** | −0.06 | 0.09** | 0.15*** | −0.08*** |

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.56 | 0.29 |

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.10 (two-tailed tests)

Annual difference in prevalence = prevalence of a work-family characteristic among college-educated women in a given year minus the prevalence among women without a high school credential. The intercept is the predicted prevalence gap during in 1976. The slope is the predicted annual change in the prevalence gap. For instance, in 1976 the prevalence of employment among college-educated white women was estimated to be 22.54 percentage points higher than the prevalence among low-educated women; from 1976 to 2011 the prevalence gap increased annually by 0.30 percentage points.

Because there was no educational gradient for this work-family form, we compared education groups that had the lowest and highest prevalence of this form. For white and Hispanic women the models compare the college-educated and some college groups, and for black women the models compare the low-educated and some college groups.

Work-Family Context

Figure 3 displays trends in the prevalence of the four work-family forms that include women with children at home. Note that the denominators for the prevalence include all women, not just women with children at home. The top left panel shows the expected steep decline in the married/not-employed with children form. The decline slowed for all education levels in the early 1990s and then gradually reversed among the low- and college-educated. By 2011 the prevalence of this form ranged from 14.2% among women with a high school (HS) credential to 21.0% among low-educated women.

Fig. 3.

Trends in work-family forms with children at home by education among women aged 25–64. The percentages reflect the prevalence of each work-family form among all women, not just among women with children at home.

The top right panel reveals a strong and growing educational gradient in the prevalence of the married/employed with children form. For instance, between 1976 and 2011, the prevalence of this form declined among low-educated women from 9.5% to 6.9% but grew among college-educated women from 14.5% to 18.5%, more than doubling the educational gap between these women from 5.0% to 11.6%. Among the middle education levels, the prevalence of this form rose until around 2000 when it stalled and began a gradual decline.

The bottom left panel reveals a small rise in the unmarried/not-employed with children form. The increase occurred mainly among women without a college degree, increasing the educational gradient in this work-family form. Between 1976 and 2011, the prevalence increased from 8.8% to 11.3% among low-educated women, from 2.9% to 6.6% among women with a HS credential or some college, and 1.4% to 1.9% among the college-educated. The gap between low- and college-educated women grew 2 percentage points, from 7.4% in 1976 to 9.4% in 2011.

The bottom right panel shows a small increase in the unmarried/employed with children form across all education levels. It is noteworthy that the prevalence of this form did not exhibit an educational gradient throughout the entire study period. For instance, women with some college were more likely to combine full-time employment and childrearing without a spouse than other women, while their college-educated peers were the least likely. It is also noteworthy that educational differences in this form were relatively small. For example, in 1976 the prevalence gap across education levels was just 1.0%. By 2011 the prevalence ranged from 4.1% among college-educated women to 6.4% among women with some college, a 2.3% gap.

Figure 4 displays trends in the four work-family forms by education level within three race/ethnic groups. In Table 1 we test whether the difference between college-educated and low-educated women in the prevalence of each work-family form significantly widened, narrowed, or persisted. Several findings are noteworthy. First, work-family context has historically been more tightly linked to one’s education level among black and Hispanic women than among white women. Second, this is becoming less true. It has become less true largely because educational differences in the four work-family forms have grown for white women but generally narrowed or held steady for black and Hispanic women. For example, in 1976 education was a fairly weak predictor of whether a white woman was married and employed with children at home, ranging from 8.9% of the low-educated and 12.7% of the college-educated, a 3.8% gap. This is in stark contrast to the 23.0% gap among black women. Educational differences in this work-family form subsequently grew among white women (p<0.001) but narrowed among black women (p<0.001) so that by 2011 the educational gaps were 14.0% and 12.7%, respectively. Third, the widening differences in work-family context across education levels shown previously in Figure 3 mainly occurred among white women. In contrast, educational differences in the four work-family forms narrowed for all but one form—unmarried/employed—among black women while the trends were directionally mixed among Hispanic women (statistical tests in Table 1). Fourth, among women with children at home, only the unmarried/employed form became more strongly linked to education level within all three race/ethnic groups.4 This work-family form is unique in that it did not exhibit an educational gradient throughout the 1976–2011 period. Rather, women with some college were more likely to be living in this form across race/ethnic groups.

Fig. 4.

Trends in work-family forms with children at home by education and race/ethnicity among women aged 25–64. The percentages reflect the prevalence of each work-family form among all women, not just among women with children at home.

Discussion

This study reveals several new and important findings about how work-family context has differentially changed by education level among working-age U.S. women during 1976 to 2011. We focused on four work-family forms that include women with children at home: married/not-employed, married/employed, unmarried/not-employed, and unmarried/employed. We found that trends in the four work-family forms exhibited substantial heterogeneity by education level and race/ethnicity. First, while differences across education levels in the prevalence of the four work-family forms widened at the population level, the differences did not widen for all race/ethnic groups. Rather, the widening primarily occurred among white women. In contrast, educational differences in the four work-family forms generally narrowed among black women and were directionally mixed among Hispanic women. These findings highlight that assessing trends in work-family context by education level without considering how education intersects with race/ethnicity can obscure meaningful differences in women’s lives.

A second important finding is that the widening differences in work-family context across education levels among white women largely reflected unique trends among the low-educated. For instance, compared with their better-educated peers, low-educated white women became increasingly less likely to be married, to be employed, to have children at home, and to combine these three roles. Although speculative, these patterns may shed light on why diverging trends in mortality since the mid-1980s are most pronounced for white women (Meara, Richards, and Cutler 2008; Montez et al. 2011). While educational disparities in work-family context among black women generally narrowed, the trends should not be interpreted as unequivocally favorable. For example, narrowing educational differences in the prevalence of the married/employed with children form (which generally predicts good health) among black women reflected a declining prevalence of this form among the college-educated rather than an increase among the low-educated.

Third, work-family context has historically been more tightly tied to one’s education level among black and Hispanic women than among white women. However, this is becoming less true. Educational differences in the four work-family forms have been growing for white women but generally shrinking or holding steady among black and Hispanic women. The reasons are unclear. One speculation is that the Civil Rights legislation of the mid-to-late 1960s may have softened the importance of education for accessing social and economic opportunities among black and Hispanic women while elevating its importance among white women.

Fourth, with one exception, when we found widening educational differences in work-family life, they reflected trends that were directionally similar among education groups but varying in magnitude. The one exception concerned married/employed white women with children at home. The prevalence of this form increased among the college-educated but decreased among the low-educated. It is intriguing that the diverging trends in this work-family form mirror trends in death rates of white women during 1986–2006 (Montez and Zajacova 2013a). Future studies should investigate whether the two trends are related.

Fifth, among women with children at home, only the unmarried/employed form became more strongly patterned by education level within all three race/ethnic groups. Interestingly, educational differences in this work-family form were not defined by the conventional educational gradient. Rather, women with a high school or some college education were most likely to be unmarried and employed full-time with children at home. One implication is that these trends—while potentially important for women’s health and mortality—are unlikely to have contributed to the widening educational gradient in these outcomes. It also serves as a reminder that, while many individual dimensions in work-family life are patterned by education, the ways that women combine these roles may not be so neatly patterned.

Work-Family Conflict

Although we did not have direct measures of work-family conflict, the findings nonetheless provide insights into work-family conflict because certain work-family forms carry heightened risks of role interference. This is particularly true for the unmarried/employed with children form (Winslow 2005). During 1976–2011 the prevalence of the unmarried/employed with children at home form marginally increased. The prevalence tended to be highest among women with some college education, regardless of race/ethnicity. Women with some college or a high school credential—who represented 57% of the female population in 2011—were more likely to be juggling full-time employment and childrearing without a spouse than any other education level. These patterns support Theda Skocpol’s (2000) contention that the “missing middle” is most in need of social policies to assist working parents. The moderately increasing prevalence of the unmarried/employed with children form and its concentration among the majority middle underscore the need for work-family policies on the national agenda.

Among women with children at home, the married/employed form also carries a risk of work-family conflict, although generally lower than the unmarried/employed form (Winslow 2005) partly due to the buffering effects of marriage. Nonetheless, being married and employed with children at home generally predicts the best health outcomes among the four forms we studied (Martikainen 1995; Verbrugge 1983; Waldron et al. 1998). To the extent that this form promotes good health (e.g., Waldron et al. 1998 find support for a causal effect, net of health selection into work-family roles), it is disconcerting that its prevalence declined among black women and low-educated white women. The reasons for the decline are unclear. Some scholars assert that combining employment and marriage has become incompatible for disadvantaged mothers due to provisions of welfare-to-work policies (Cherlin and Fomby 2005).

Limitations and Next Steps

One potential limitation is that we did not have consistent data on cohabitation across the period so we relied on marital status as our sole indicator of partnership status and we focused on heterosexual couples. Also, we used a binary indicator of parental status instead of number of children. As we mentioned in the methods section, in ancillary analyses we found that using an indicator of two or more children produced similar trends. Extant studies have found that using parental status or number of children gives similar results when predicting work-family conflict (Nomaguchi 2009; Winslow 2005). We did not have information about children living outside the home but that data is not central to our concern about the daily demands of work-family life. Also, we did not examine the trends by immigration and generational status. That issue deserves a separate study given the complex relationship between these factors and work-family life (see Brown, Hook, and Glick 2008). Nonetheless, our trends for Hispanic women should be interpreted cautiously. We also stress that the link between trends in work-family life and work-family conflict are only suggestive, as the latter reflects a host of structural and psychological aspects not measured here (Voydanoff 2004). One final note concerns compositional changes. As average education levels have risen across time, the low-education group may comprise increasingly disadvantaged women. However, compositional changes do not appear to fully account for trends in women’s work-family context, at least from 1970 to 1995 (Blau 1998).

Future research documenting work-family trends and testing associations between such trends and health outcomes should integrate the qualitative dimensions of work-family life (see Voydanoff 2004). For example, temporal trends in psychosocial demands and control over work time (Karasek and Theorell 1990) should be taken into account as well as potentially changing benefits of marriage due to rising educational homogamy (Schwartz and Mare 2005). Future research should also investigate the factors driving the differential trends by education level. Some potentially important factors include the bifurcation of the labor market along human capital lines, the deterrent effect of financial uncertainty on decisions to marry (Smock, Manning, and Porter 2005), and the availability and affordability of child care. For instance, low-income women and women employed in nonstandard schedules face disproportionate constraints in securing child care (Gornick and Meyers 2003). We also propose conducting parallel analyses on work-family dynamics in European countries that have experienced similar trends in work-family life but have implemented generous social protection policies.

Conclusion

Trends in work-family context among U.S. women with children at home exhibited substantial heterogeneity by education level during the last 35 years. Educational differences in work-family context widened among white women, with low-educated women diverging from their more-educated peers. In contrast, educational differences in work-family context generally narrowed among black women and were directionally mixed among Hispanic women. Among women with children at home, only the unmarried and employed work-family form—which carries an elevated risk of work-family conflict—became more strongly linked to one’s education level within all three race/ethnic groups that we studied. This work-family form was most common among women with a HS credential or some college education (who were the majority) and its prevalence increased moderately during the study period. Taken together, these trends underscore recent calls (Damaske 2011; Heymann 2000; Williams and Boushey 2010) to elevate work-family policy on the national agenda.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

In ancillary analyses, we assessed the sensitivity of the trends to using a narrower age range, 25–54 years. The results were similar to the 25–64 group.

Starting in 1995 respondents could select “unmarried partner” as their relationship to the household head. Direct estimates of cohabiting unions based on this information tend to undercount them (Kreider 2008). Indirect estimates of cohabiting unions using the CPS household rosters have been proposed (see Casper and Cohen 2000). In 2007 the CPS added questions to better identify cohabitating unions. In ancillary analyses (available on request), we assessed trends from 1995 in the prevalence of unions that were either marital or cohabiting. Trends among the combined group were similar to trends among the married group. Thus, we focus on legal marital status in this study. We also separately assessed trends in cohabiting unions starting in 1995. Cohabitation increased at a fairly similar pace across education levels for the three race/ethnic groups, but especially so among low-educated white women.

Respondents may be interviewed in two consecutive March surveys due to the rolling sample design of the CPS. Thus, “n” is the number of observations, not the number of women.

We did not find this type of diverging trend in any other work-family form, including the four forms without children in the household as shown in Table A in the online supplement.

References

- Allen TD, Armstrong J. Further examination of the link between work-family conflict and physical health: The role of health-related behaviors. American Behavioral Scientist. 2006;49(9):1204–1221. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett RC, Hyde JS. Women, men, work, and family. American Psychologist. 2001;56(10):781–796. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.10.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Buxton O, Ertel KA, Okechukwu C. Managers' practices related to work-family balance predict employee cardiovascular risk and sleep duration in extended care settings. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2010;15:316–329. doi: 10.1037/a0019721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, O’Donnell EM. The Pro-family Workplace: Social and Economic Policies and Practices and Their Impacts on Child and Family Health. In: Landale NS, McHale SM, Booth A, editors. Families and Child Health. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 157–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Milkie MA. Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:705–725. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Robinson JP, Milkie MA. Changing rhythms of American family life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blau FD. Trends in the well-being of American women, 1970–1995. Journal of Economic Literature. 1998;36:112–165. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Hook JV, Glick JE. Generational differences in cohabitation and marriage in the U.S. Population Research and Policy Review. 2008;27(5):531–550. doi: 10.1007/s11113-008-9088-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byron K. A meta-analytic review of work family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2005;67:169–198. [Google Scholar]

- Casper LM, Cohen PN. How does POSSLQ measure up? Historical estimates of cohabitation. Demography. 2000;37(2):237–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. Demographic trends in the United States: A review of research in the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:403–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Fomby P. Welfare, work, and changes in mothers’ living arrangements in low-income families. Population Research and Policy Review. 2005;23(5):543–565. [Google Scholar]

- Coontz S. Why gender equality stalled. The New York Times. 2013 Feb 17;:SR1. [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM, Saito Y. Trends in healthy life expectancy in the United States, 1970–1990: gender, racial, and educational differences. Social Science and Medicine. 2001;52(11):1629–1641. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby FJ. Juggling: The unexpected advantages of balancing career and home for women and their families. New York: The Free Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Lange F, Meara E, Richards S, Ruhm CJ. Explaining the rise in educational gradients in mortality. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2010. NBER Working Paper 15678. [Google Scholar]

- Damaske S. For the family? How class and gender shape women's work. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood DT, Jencks C. The uneven spread of single-parent families: What do we know? Where do we look for answers? In: Neckerman KM, editor. Social inequality. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. pp. 3–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ertel KA, Koenen KC, Berkman LF. Incorporating home demands into models of job strain: Findings from the Work, Family & Health Network. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2008;50(11):1244–1252. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31818c308d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frech A, Damaske S. The relationships between mothers’ work pathways and physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2012;53(4):396–412. doi: 10.1177/0022146512453929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedan B. The feminine mystique. New York: Norton; 1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frone MR. Work-family conflict and employee psychiatric disorders: The National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2000;85(6):888–895. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frone MR, Barnes GM, Farrell MP. Relationship of work-family conflict to substance use among employed mothers: The role of negative affect. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1994;56(4):1019–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Frone MR, Russel M, Cooper ML. Relation of work-family conflict to health outcomes: A four-year longitudinal study of employed parents. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 1997;70(4):325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Fry R, Cohn DV. Women, men and the new economics of marriage. Pew Research Center; 2010. [Cited 1 July 2012]. Available via http://www.nd.edu/~bruce/Statistics/economics-of-marriage.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis C. Mothers but not wives: The increasing lag between nonmarital births and marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(1):264–278. [Google Scholar]

- Goesling B. The rising significance of education for health. Social Forces. 2007;85(4):1621–1644. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C. The long road to the fast track: Career and family. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2004;596:20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gornick JC, Meyers MK. Families that work: Policies for reconciling parenthood and employment. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Heymann J. The widening gap: Why America's working families are in jeopardy and what can be done about it. New York: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Isen A, Stevenson B. [Cited June 2012];Women's education and family behavior: Trends in marriage, divorce, and fertility. 2010 NBER Working Paper 15725. Available via http://www.nber.org/papers/w15725. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PB, Williams DR. The intersection of race, gender, and SES: Health paradoxes. In: Schulz AJ, Mullings L, editors. Gender, race, class, & health: Intersectional approaches. San Francisco, CA, US: Jossey-Bass; 2006. pp. 131–162. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen NWH, Kant IJ, van Amelsvoort LGPM, Kristensen TS, Swaen GMH, Nijhuis FJN. Work-family conflict as a risk factor for sickness absence. Occupational and Environmental Medcine. 2006;63(7):488–494. doi: 10.1136/oem.2005.024943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy work. New York: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM. Improvements to demographic household data in the Current Population Survey: 2007 working paper. Housing and Household Economic Statistics Division: U.S. Bureau of the Census; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS, Bradatan C. Hispanic families in the United States: Family structure and process in an era of family change. In: Tienda M, Mitchell F, editors. Hispanics and the Future of America. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, McLaughlin DK, Kephart G, Landry DJ. Race and the retreat from marriage: A shortage of marriageable men? American Sociological Review. 1992;57(6):781–799. [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen P. Women's employment, marriage, motherhood and mortality: A test of the multiple role and role accumulation hypotheses. Social Science & Medicine. 1995;40(2):199–212. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)e0065-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP. Women’s education and family timing: Outcomes and trends associated with age at marriage and first birth. In: Neckerman KM, editor. Social inequality. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. pp. 79–118. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP. Trends in marital dissolution by women’s education in the United States. Demographic Research. 2006;15:537–560. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography. 2004;41:607–628. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Casper L. Growing diversity and inequality in the American family. In: Farley R, editor. State of the Union. Vol. 2. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Meara ER, Richards S, Cutler DM. The gap gets bigger: Changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981–2000. Health Affairs. 2008;27(2):350–360. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Population Center. Minnesota Population Center and State Health Access Data Assistance Center, Integrated Health Interview Series: Version 5.0. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2012. Available via http://www.ihis.us. [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, Dempster-McClain D, Williams RM. Successful aging: A life-course perspective on women's multiple roles and health. American Journal of Sociology. 1992;97(6):1612–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Montez JK, Hummer RA, Hayward MD, Woo H, Rogers RG. Trends in the educational gradient of U.S. adult mortality from 1986 through 2006 by race, gender, and age group. Research on Aging. 2011;33(2):145–171. doi: 10.1177/0164027510392388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montez JK, Zajacova A. Trends in mortality risk by education level and cause of death among US white women from 1986 to 2006. American Journal of Public Health. 2013a;103(3):473–479. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montez JK, Zajacova A. Why has the eductional gradient of U.S. mortality increased among white women? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013b;54(2):165–181. doi: 10.1177/0022146513491066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Explaining divergent levels of longevity in high-income countries. Washington D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2011. Panel on understanding divergent trends in longevity in high-income countries. Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi KM. Change in work-family conflict among employed parents between 1977 and 1997. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, Binstock RH, Boersch-Supan A, Cacioppo JT, Carnes BA, Carstensen LL, Fried LP, Goldman DP, Jackson J, Kohli M, Rother J, Zheng Y. Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening and may not catch up. Health Affairs. 2012;31(8):1803–1813. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Bumpass LL. The topography of the divorce plateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research. 2003;8:245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Repetti RL, Matthews KA, Waldron I. Employment and women's health: Effects of paid employment on women's mental and physical health. American Psychologist. 1989;44(11):1394–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, Morgan P, Offutt K. Education and the changing age pattern of American fertility: 1963–1989. Demography. 1996;33(3):277–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos E, Lahelma E, Rahkonen O. Work-family conflicts and drinking behaviours among employed women and men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg S. Why I want women to lean in. Time Magazine. 2013;181:44–45. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CR, Mare RD. Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography. 2005;42(4):621–646. doi: 10.1353/dem.2005.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skocpol T. The missing middle. New York: W.W. Norton & Company; 2000. A Century Foundation Book. [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter A-M. Why women still can't have it all. The Atlantic Magazine. 2012;310:84–102. [Google Scholar]

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, Porter M. "Everything's There Except Money": How Money Shapes Decisions to Marry Among Cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:680–696. [Google Scholar]

- Spain D, Bianchi SM. Balancing act: Motherhood, marriage, and employment among American women. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Multiple identities: Examining gender and marital status differences in distress. American Sociological Review. 1986;51(2):259–272. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey Design and Methodology, Technical Paper. 2006;66 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. CPS Historical Time Series Tables. Table A-2. Percent of people 25 years and over who have completed high school or college, by race, Hispanic origin and sex: Selected years 1940 to 2012. [Accessed September 5, 2013]; (n.d.). at http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/historical/

- Väänänen A, Kumpulainen R, Kevin MV, Ala-Mursula L, Kouvonen A, Kivimaki M, Toivanen M, Linna A, Vahtera J. Work-family characteristics as determinants of sickness absence: A large-scale cohort study of three occupational grades. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2008;13(2):181–196. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.13.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM. Multiple roles and physical health of women and men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(1):16–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P. The effects of work demands and resources on work-to-family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66:398–412. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron I, Weiss CC, Hughes ME. Interacting effects of multiple roles on women's health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1998;39(3):216–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JC. Unbending gender: Why family and work conflict and what to do about it. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JC, Boushey H. The three faces of work-family conflict. The poor, the professionals, and the missing middle. 2010 Available at: http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2010/01/pdf/threefaces.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy, Second Edition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow S. Work-family conflict, gender, and parenthood, 1977–1997. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:727–755. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Morgan SP, Wang Z, Gu D, Yang C. A multistate life table analysis of union regimes in the United States: Trends and racial differentials, 1970–2002. Population Research and Policy Review. 2012;31(2):207–234. doi: 10.1007/s11113-011-9217-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.