Abstract

We examine prevalence of four compensatory strategies (assistive devices, receiving help, changing frequency, or method of performance) and their immediate and long-term relationship to well-being. A total of 319 older adults (>70 years) with functional difficulties at home provided baseline data; 285 (89%) provided 12-month data. For 17 everyday activities, the most frequently used strategy was changing method of performance (M = 10.27 activities), followed by changing frequency (M = 6.17), assistive devices (M = 5.38), and receiving help (M = 3.37; p = .001). Using each strategy type was associated with functional difficulties at baseline (ps < .0001), whereas each strategy type except changing method predicted functional decline 12 months later (ps < .0001). Changing frequency of performing activities was associated with depressed mood (p < .0001) and poor mastery (p < .0001) at both baseline and 12 months (ps < .02). Findings suggest that strategy type may be differentially associated with functional decline and well-being although reciprocal causality and the role of other factors in these outcomes cannot be determined from this study.

Keywords: adaptation, assistive devices, depression, frailty, home care

Older adults overwhelmingly seek to age in their own home and community with quality of life (Gitlin, Szanton, & Hodgson, 2014). Aging in one’s own long-term or preferred residence is associated with lower levels of depression and greater functional independence (Marek et al., 2005). Nevertheless, with age, most older adults experience functional difficulties due to age-associated changes and chronic conditions such as arthritis, vision loss, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, or Parkinson’s disease. These common conditions impinge on an individual’s ability to participate in everyday activities such as shopping, self-care, visiting family and friends, or pursuing discretionary activities. In turn, functional difficulties threaten the ability to remain living at home and are also associated with social isolation, reduced quality of life, and poor health outcomes, including hastened mortality (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] & The Merck Company Foundation, 2007; Gitlin et al., 2009; Gitlin et al., 2006 (Gitlin, Hauck et. al; Gitlin, Winter, Dennis, & Hauck, 2008). Despite the immense impact of functional difficulties on everyday life and well-being, insufficient attention has been expended on the role of physical function in health and human services. Furthermore, little is understood as to the strategies older adults employ to address physical limitations and ameliorate their potential negative consequences.

The small body of research on this topic suggests that older adults respond to functional difficulties by adapting a wide range of strategies to compensate for losses in the ability to carry out desired activities (Gignac, Cott, & Badley, 2000; Kincade-Norburn et al., 1995; Manton, Corder, & Stallard, 1993; Wahl, Oswald, & Zimprich, 1999). Also, it appears that some strategies have positive outcomes while others may have negative consequences for well-being and daily functioning (Agree, Freedman, & Sengupta, 2004; Freund & Baltes, 1998; Gignac et al., 2000). For example, relying on others for help to carry out daily activities has been associated with low self-efficacy (Verbrugge & Sevak, 2002); decreasing one’s frequency of participation in an activity has been linked to depression (Williamson, Shaffer, & Schulz, 1998). In contrast, performing desired activities with the aid of assistive devices has been associated with enhanced perceptions of independence (Mann, Hurren, Tomita, & Charvat, 1995). In visually impaired older adults, use of optical devices has been associated with reduced functional disability and depressive symptoms (Horowitz, Brennan, Reinhardt, & MacMillan, 2006). Use of some compensatory strategies (e.g., seeking help from others) has also been associated with lower levels of suicidal ideation, even after controlling for depressive symptomatology (Fiske, Bamonti, Nadorff, Petts, & Sperry, 2013). Research from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) involving a national probability sample of 8,077 older adults shows that 25% of this sample used devices, 6% reduced their activities, 18% had difficulties although they used accommodations, and 21% received help. Successful strategy use was associated with improved and continued engagement in activities (Freedman et al., 2013).

Our study builds on and extends these previous efforts. Our purpose was twofold. First, we examined the prevalence of the use of common compensatory strategies by older adults 70 years of age or older who were living at home with a range of functional difficulties. We considered four types of strategies categorized as either extraindividual (i.e., external to the person such as using assistive devices or receiving help) or intraindividual or behavioral changes intrinsic to the person (i.e., changing the frequency of engaging in an activity or changing the method of performing an activity such as allowing more time to complete a task or sitting instead of standing; Gignac et al., 2000; Verbrugge & Sevak, 2002). Second, we examined the associations of using each of these strategies to three important indices of well-being—level of functional difficulties, depressive symptoms, and perceived mastery—at baseline and then 12 months later. Understanding the prevalence of compensatory strategy use and their association with well-being can help inform the development of interventions that instruct in the use of effective compensatory strategies to minimize functional losses at home.

To understand compensatory strategy use, we drew on the motivational theory of life-span development (Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010; Schulz & Heckhausen, 1996). This theory suggests that threats to or actual losses in the ability to control important outcomes such as performing self-care activities may motivate individuals to use strategies that offset or buffer threats and real losses to control of environmental contingencies. To the extent that strategies are effective in attaining functional goals, threats to or actual losses of control are minimized resulting in positive affect, a sense of mastery, and better physical health (Gitlin, Hauck, Dennis, & Schulz, 2007; Wrosch, Schulz, & Heckhausen, 2002). The theory also posits the opposite: Negative consequences can result when functional goals are not attained, and perceived or actual threats to control occur. A growing evidence base supports both the psychological and functional advantages of using specific compensatory strategies that enhance personal control (Gitlin et al., 2007; Heckhausen et al., 2010).

Based on previous research and our theoretical framework, we posited several predications. First, although we did not have any a priori predictions concerning the prevalence of the use of the four compensatory strategies of interest, we assumed that use of any one of these would be associated with greater functional difficulties as demonstrated in previous studies. Second, we hypothesized that changes to the frequency of performing activities (either increasing or decreasing frequency) would be associated with negative emotional consequences both initially and over time. As the motivational theory of life-span development suggests, use of strategies that do not support engagement or one’s ability to perform meaningful activities can result in poor mental health outcomes. Disengagement from activities is a known risk factor for depressive symptoms and cognitive (Bassuk, Glass, & Berkman, 1999) and functional (Simonsick et al., 1993) decline. We expected that restricting engagement in potentially valued activities as a compensatory mechanism would interfere with attaining functional goals and thus exacerbate the loss of control, resulting in depressed mood and lower mastery. Similarly, increasing the frequency of an activity, such as having to take more medications, would signal decline. In contrast, we reasoned that using other types of compensatory strategies such as assistive devices or changing the method of performing an activity facilitated continued engagement in desired activities and the realization of functional goals and thus would be associated with better outcomes initially and over time. Third, we expected that reliance on help to accomplish activities would be associated with greater functional decline and also predict further decline over time (incident disability). We reasoned that as relying on help is not a culturally preferred approach in the United States, it may not be used unless other compensatory strategies fail. In turn, reliance on others to perform valued activities may signal decline and increasing dependency, which would be perceived negatively.

Participants for this study were enrolled in a randomized trial of a home intervention (Advancing Better Living for Elders; ABLE), the purpose of which was to provide older adults with a range of compensatory techniques to help them engage in their own self-identified daily activity goals. The results for this trial have been reported previously showing improvement in daily function, self-efficacy, overall well-being, and a reduction in mortality (Gitlin, Winter, Dennis, Corcoran et al., 2006; Gitlin, Hauck, Winter, Dennis, & Schulz, 2006; Gitlin et al., 2008). Our interest in this present study was in the compensatory strategies that were used by study participants at the time of study enrollment and prior to receiving intervention as well as the long-term effects of employing these compensatory strategies using longitudinal analyses and after controlling for intervention effects (i.e., group allocation).

Method

Study Sample and Procedures

Study participants were 70 years or older, recruited between 2000 and 2003 from social services agencies and media announcements in an urban area. Participants were cognitively intact (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score > 23 on a 0 to 30 scale; Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975), English-speaking, and although they reported functional difficulties, were not receiving home care or other services to address activity limitations (Gitlin et al., 2007). Participants were initially interviewed at baseline, then following randomization to the intervention (ABLE) or no-treatment control group, were reinterviewed at 6 and 12 months by trained interviewers who remained masked to group allocation. This study utilized baseline and 12-month data. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at the baseline interview using an approved form by the institutional review board at Thomas Jefferson University.

Measures

Background characteristics included age, sex, race (White, non-White), education (<high school, high school, >high school), living arrangement (alone, with others), and financial difficulty paying for basics (1 = not at all difficult to 4 = very difficult to pay).

We used a standard self-report measure of functional difficulties that included 17 areas: 6 activities of daily living items (ADLs; that is, dressing above and below the waist, grooming, bathing or showering, toileting, and eating), 5 instrumental activities of daily living items (IADLs; that is, light housework, errands/shopping, preparing meals, taking medication, telephone use), and 6 mobility-related activities items (i.e., getting in/out of bed, walking indoors, walking one block, climbing one flight of stairs, moving in/out of chair, moving in/out of bed; Ettinger et al., 1997; Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffee, 1963; Lawton & Brody, 1969). Participants rated their difficulty with each task in the past month on 5-point scales (1 = No difficulty to 5 = Unable to do due to health problems). An overall functional difficulty index score was derived by computing average difficulty level across items, with higher scores indicating greater difficulty (Cronbach’s α = .83 for this sample).

Following Fried et al.’s (1996) approach, for each functional item, regardless of difficulty level (no difficulty to unable to do), participants were asked whether they used each strategy type (yes/no) in this order: assistive devices, help from others, change in frequency of performing the activity, or change in method. Index scores were derived for each strategy type by computing the mean number of activities the adaptation was used within each functional domain and across all items (0 to 17 activities).

The measure of change in frequency was complicated by that fact that change can be either an increase or a decrease. We found that change was mostly in the direction of decreasing frequency (e.g., for housework 62.1% decreased, 1.9% increased). The sole exceptions to this were for toileting and taking medications. For changes in toileting, 29.8% reported greater frequency, 6.6% lower frequency. For taking medications, 16.6% reported greater frequency and 3.4% lower frequency. For analytical purposes, we coded change as any change (increase or decrease).

Depressive symptomatology was measured using the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) that assesses frequency of depressive symptoms during the past week on a scale from 0 (rarely/none of the time) to 3 (most or almost all the time). Total scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater depressive symptomatology (Cronbach’s α = .79 for this sample).

To measure personal mastery, we used a seven-item Mastery Scale (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978). For each item (e.g., “I have little control over the things that happen to me”; “There is really no way I can solve some of the problems I have”), individuals indicate the extent of their agreement, from 1 (disagree a lot) to 4 (agree a lot; Cronbach’s α = .65 for this sample).

Data Analytic Strategy

Frequencies of self-reported use of four compensatory strategies for 17 functional activities were examined. To assess differences in prevalence of strategy type (assistive device use, receiving help, change in frequency, and change in method) by activity type (ADL, IADL, and mobility), a repeated-measures ANCOVA was conducted, with repeated measures on both use of strategies (four levels) and type of activity (three levels). Age, sex, race, years of education, marital status, and financial difficulty were selected a priori as covariates on the basis of their associations with these outcomes, as reported in previous research.

The prevalence of zeros (e.g., strategy not used) in the frequency counts for some strategies within functional domains (e.g., use of assistive devices for ADLs) was a concern for the repeated-measures ANCOVA because of the potential for violating the normality assumption. To address this, type of strategy (assistive device use, receiving help, change in frequency, and change in method) and domain (ADL, IADL, and mobility) were stratified and examined in separate repeated-measures ANCOVAs. In both analyses, frequencies of zeros were very low, reflecting the prevalence of functional limitations in the sample. In each subsequent ANCOVA, age, sex, race, years of education, marital status, and financial difficulty served as covariates, as in the earlier ANCOVA.

To determine the associations of each strategy type to dimensions of well-being (functional difficulties, depressed mood, and personal mastery), multiple regression (MR) analyses were conducted separately for each strategy type by each dependent variable. In separate MRs, baseline functional difficulty, depressed mood, or personal mastery scores served as the dependent variable. In each regression, the independent variable was the number of activities for which each of the four compensatory strategies was used. Covariates for all analyses included age, sex, race, and financial difficulty. Similar analyses were conducted for 12-month outcomes with the addition of treatment assignment (experimental or control), change in functional difficulties (T3-T1), and baseline values of the relevant dependent variable as covariates.

SPSS Version 15.0 was used, with significance level set at .05. All analyses were two-sided.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 319 participants enrolled, 285 (89%) were available for the 12-month follow-up. Of the 34 participants lost to follow-up, 14 died, 1 was hospitalized, 4 reported dissatisfaction with the study, 5 entered nursing homes, 8 could not be located, and 2 could not participate due to deteriorating health. As reported elsewhere, there were no large or statistically significant differences between the 34 participants lost to follow-up and the participants included in the current analyses, except for cognitive status and number of health conditions (Gitlin et al., 2008). Compared with participants who discontinued participation, participants in the follow-up analyses had slightly lower MMSE scores (M = 26.8 vs. 27.8; p = .003) and more health conditions (M = 7.1 vs. 6.0; p = .14).

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most participants were female (81.8%) with slightly more than a third having a higher level of education than high school (36.7% > high school education). Nearly half (45.5%) were African American. At baseline, participants reported mostly having “some” functional difficulties across the 17 activities (M = 47.8, SD = 12.07, range = 21.00-82.00), and moderate levels of mastery (M = 19.1, SD = 4.2, range = 7-28) and mild to moderate depressive symptomatology (M = 14.5, SD = 10.8, range = 0-56). At 12-month follow-up, participants reported a slight decline in functional difficulty (M = 44.6, SD = 11.8, range = 19-80) and similar levels of mastery (M = 19.0, SD = 4.5, range = 7-28) and depressive symptomatology (M = 13.6, SD = 10.6, range = 0-54) as at baseline.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline (N = 319) and Baseline and 12-Month (N = 285) Scores for Dependent Variables.

| M (SD) | Range | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 79.0 (5.9) | 70.0–96.56 | |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 52.7 | ||

| African American | 45.5 | ||

| Other | 1.9 | ||

| Gender (% female) | 81.8 | ||

| Education (% > high school) | 36.7 | ||

| Financial difficulty | |||

| Not at all | 24.1 | ||

| Not very | 18.8 | ||

| Somewhat | 39.5 | ||

| Very | 16.9 | ||

| Marital status (% married) | 18.5 | ||

| Living arrangement (% living alone) | 61.8 | ||

| Baseline | |||

| Functional difficulty | 47.8 (12.07) | 21.00−82.00 | |

| Depression symptoms (CES-D) | 14.5 (10.8) | 0–56 | |

| Mastery | 19.1 (4.2) | 7–28 | |

| 12-month | |||

| Functional difficulty | 44.6 (11.8) | 19–80 | |

| Depressive symptoms | 13.6 (10.6) | 0–54 | |

| Mastery | 19.0 (4.5) | 7–28 |

Note. Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding differences. CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale.

Prevalence of Compensatory Strategies Used by Functional Domain at Baseline

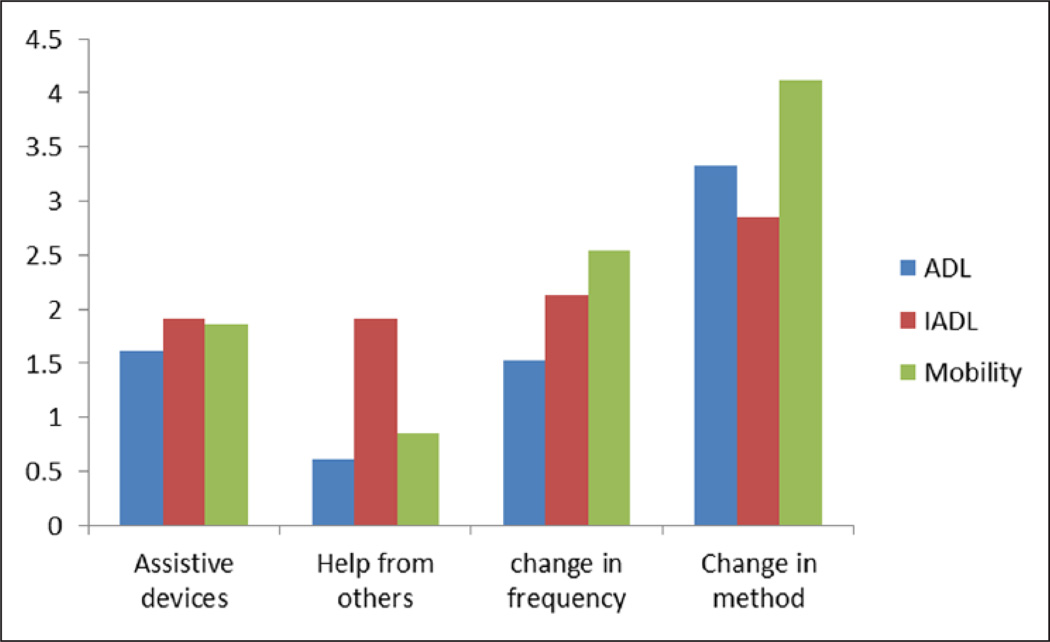

Overall, at baseline, change in the method of performance was the most common type of compensatory strategy used across all functional domains (ADL, IADL, Mobility), followed by the change in frequency of performing activities, device use, and receiving help (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean (SD) Number of Activities for Which Each Compensatory Strategy Type Was Used by Functional Domain and Overall at Baseline (N = 319).

| Assistive devices |

Help from others |

Change in frequency |

Change in method |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADL | 1.62 (0.99) | 0.61 (1.09) | 1.53 (1.57) | 3.33 (1.66) |

| IADL | 1.91 (1.16) | 1.91 (1.67) | 2.13 (1.26) | 2.85 (1.32) |

| Mobility | 1.86 (1.50) | 0.86 (0.86) | 2.54 (1.60) | 4.12 (1.31) |

| Overall number of activities | 5.38 (2.63) | 3.37 (2.45) | 6.17 (3.43) | 10.27 (3.27) |

Note. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

The number and type of compensatory strategies used also varied by the three functional domains assessed (ADL, IADL, mobility) at baseline for this sample. The repeated-measures ANCOVA confirmed these differences in the prevalence of compensatory strategy types by functional domains (ADL, IADL, and mobility), F(2, 311) = 3.24, p = .041, and by strategy type, F(3, 310) = 7.27, p < .0001, and also revealed an interaction (Figure 1) between functional domain and strategy type, F(6, 307) = 2.66, p = .016. Post hoc least significant difference (LSD) tests showed that all pairs were significantly different (p < .0001).

Figure 1.

Use of compensatory strategies by number and type of activities at baseline.

Note. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

The individual repeated-measures ANCOVAs confirmed these main effects. The first ANCOVA revealed a main effect for type of strategy used across all three domains, with the highest frequency reported for the use of change in method (M = 10.27, SD = 3.27), the lowest for help from others (M = 3.37, SD = 2.45), F(3, 302) = 5.34, p = .001. Change in frequency (M = 6.17, SD = 3.43) and assistive device use (M = 5.38, SD = 2.63) were intermediate. The second analysis confirmed a main effect for domain across all strategy types, with more strategies used for IADLs (M = 12.47, SD = 3.86), intermediate for ADL (M = 8.26, SD = 3.84), and the fewest number of strategies used for mobility (M = 4.5, SD = 2.12), F(2, 302) = 4.07, p = .018.

Relationship of Strategy Type to Functional Difficulty, Depressed Mood, and Mastery

At baseline, functional difficulty was associated with the greater use of all strategies—assistive device use (p < .0001), help from others (p < .0001), change in frequency (p < .0001), and change in method (p < .001). Change in 12-month functional difficulty was similarly associated with baseline use of assistive devices (p < .0001), help from others (p < .0001), and change in frequency (p < .0001). Only change in method at baseline was not associated with change in functional difficulty at the 12-month follow-up (p = .270).

Depressed mood was associated with changing the frequency of performance both at baseline (p < .0001) and 12-month follow-up (p = .017), but no other strategy types were associated with mood (Table 3). Similarly, mastery was associated only with changing frequency of performance at both baseline (p < .0001) and 12-month follow-up (p = .018). The more activities for which individuals changed the frequency of their performance, the greater the depressive symptoms, the lower their perceived mastery, and the greater their functional difficulties.

Table 3.

Functional Difficulty, Depression, and Mastery at Baseline (N = 319) and 12 months (N = 285) in Relation to Each Baseline Compensatory Strategy.

| Functional difficulty |

Depression |

Mastery |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

12-month |

Baseline |

12-month |

Baseline |

12-month |

|||||||

| Beta | t(p) | Beta | t(p) | Beta | t(p) | Beta | t(p) | Beta | t(p) | Beta | t(p) | |

| Assistive device use | .21 | 3.94(<.0001) | .205 | 4.103(<.0001) | .014 | 0.25(.803) | .05 | 1.232(.219) | .02 | 0.403(.687) | −.02 | 0.324(.745) |

| Help from others | .40 | 7.96(<.0001) | .320 | 6.633(<.0001) | −.01 | 0.25(.800) | −.01 | 0.270(.787) | −.09 | 1.69(.092) | −.10 | 1.898(.059) |

| Change in frequency | .33 | 6.16(<.0001) | .312 | 6.361(<.0001) | .27 | 5.03(<.0001) | .11 | 2.41(.017) | −.282 | 5.22(<.0001) | −.13 | 2.373(.018) |

| Change in method | .19 | 3.41(<.001) | .06 | 1.106(.270) | .07 | 1.26(.210) | .072 | 1.60(.111) | −.02 | 0.336(.737) | .00 | 0.001(.999) |

Note. At baseline, each regression controlled for age, race, gender, and financial difficulty. At 12 months, each regression controlled for age, race, gender, financial difficulty, treatment assignment, change in function (T3-T1), and baseline values of dependent variable.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies, we found that a large cohort of older adults living at home with functional difficulties reported using two broad categories of compensatory strategies: external (e.g., devices, help from others) and intrinsic (e.g., frequency of performance, change in method) approaches on study entry. The most commonly reported adaptation was changing the method by which activities were performed. In contrast, the strategy least used by this sample was receiving help from others. Overall, adaptations were implemented for IADL-related activities more often than for the other two functional domains considered (ADL and mobility). This most likely reflected the functional status of this group (i.e., a group with incipient disability). However, the types of strategies employed depended on the functional domain (ADL, IADL mobility), as revealed in the significant interaction.

We operationally defined strategy use by counting the number of activities within each domain (ADL, IADL, mobility) for which each strategy type was used. It was not possible to examine the exclusive use of any one strategy type by functional domain or activity as there was no single preferred approach. Use of strategies was not mutually exclusive—Participants used one to four strategies for any one functional domain and specific activity. This suggests that responding to and self-managing functional challenges is complex and appears to involve the use of a combination of strategies depending on the activity and context. The selection of a particular strategy may reflect the confluence of various factors including the person’s capabilities, access to resources (assistive devices or help), preferred approach to performing the activity, and other social (presence of others) and physical environmental contingencies. Future research is warranted to understand the contextual factors influencing the adoption and use of compensatory strategies for the self-management of functional challenges.

Consistent with previous research, we found that use of each compensatory strategy was associated with overall functional difficulty at baseline. Our findings provide further evidence that older adults with even a little or “some” self-reported functional challenges adopt strategies to actively cope (Tabbarah, Silverstein, & Seeman, 2000). Hence, adopting a repertoire of compensatory strategies appears integral to self-management and the process of aging at home with functional challenges.

The number of activities at baseline for which a participant changed frequency, used assistive devices, or received help from others was associated with further functional decline at 12 months, whereas that was not the case for the use of changing the method of performance. As change in functional difficulty level from baseline to 12 months represents incident disability, the number of activities for which a person uses these strategies appears to be a marker of new disability 1 year later. This is consistent with other research showing that some strategies such as requiring help from others are a predictor of functional decline and mortality (Hoenig et al., 2006; Min, Elliott, Wenger, & Saliba, 2006). However, it is unclear why this is the case. One explanation may be that those who rely on help from others or use assistive devices have more functional impairment to begin with, or may have previously tried to change the method of performance but found it ineffective. Also, receiving help, using assistive devices, or changing frequency may inadvertently compromise the level of physical exertion an individual needs to expend in an activity, resulting in reduced physiological capacity over time and further decline.

Our result concerning assistive device use is inconsistent, however, with a previous study that found that device use was associated with greater functional independence over time (Mann et al., 1995). In contrast, we found that only changing one’s method of performing an activity may prevent incident functional difficulties.

Our findings do not completely support motivational theory predictions as it concerns functional outcomes. We cannot know the extent to which reduction in frequency is an adaptive response to losses or an unfortunate consequence of loss in function over time. Similarly, using more assistive devices to attain goals is arguably an adaptive response but it may still not be sufficient to make up for functional losses.

As to poor mental health, only one type of strategy—changing frequency of performing an activity—was associated with both greater depressed mood and lower perceived mastery at baseline. Likewise, this was the only strategy predictive of depressed mood and poor mastery 12 months later, even after controlling for change in function. This finding lends some support to the motivational theory of life-span development as it concerns psychosocial well-being; it suggests that the pathway between functional decline and depressive symptoms may be through the type of compensatory response that individuals adopt (Lenze et al., 2001). As changing the frequency of performance for this sample primarily reflected a reduction in participation in an activity, we speculate that this may represent a form of withdrawal from being able to attain personal function goals. In turn, this may lead to feelings of a loss of control resulting in poor mental health outcomes. In contrast, using other types of compensatory strategies (assistive devices, changing method of performing an activity) may enable older adults to continue some level of participation and hence maintain a sense of well-being. This may be the case even when as discussed above use of assistive devices and receiving help did not change functional outcomes; that is, participants still experienced functional decline despite using compensatory strategies.

It is noteworthy that relying on help did not affect mood, suggesting that continued engagement in daily activities regardless of methodology is paramount to well-being. Our finding is consistent with recent national data from the NHATS showing that adaptations in response to declines in mobility and self-care such as using assistive devices are all associated with increased well-being and activity participation (Freedman, Agree, Cornman, Spillman, & Kasper, 2014).

Of concern is that changing frequency in response to functional difficulties was the second most frequently used compensation technique by this group. Older adults may be using this approach as a natural response to having difficulty performing an activity without understanding that it may place them at risk for disengagement. They may not be aware of other strategies such as assistive devices, help, or other modalities for addressing emerging limitations.

A few study limitations are worthy of notation. First, functional difficulties and compensatory strategy use were self-reported, leaving room for self-report bias. Of interest for future research would be to examine the relationship between objective measures of physical function and strategy use such as direct observation or video-recordings. Also, we examined self-reported strategy use and are therefore unable to confirm actual use or whether strategies were effectively used. A related point is that the four items that query about the compensatory strategies are single items that have not been validated. Nevertheless, as single items, they have face validity and have been used in other studies previously. Second, the sample consisted of older adults reporting some physical limitations. It excluded those with no limitations, those with severe limitations, and those living in assisted living and nursing homes. This may limit the generalizability of the results to both higher and lower functioning older adults. Also, the sample is mostly female and there may be differential use of strategies based on gender. Future research should examine compensatory strategy use among the entire continuum of functional challenges and for different demographic subgroups. Some evidence suggests, for example, that older adults use compensatory strategies early on prior to the onset of functional disability, representing a preclinical disability stage (Wolinsky, Miller, Andresen, Malmstom, & Miller, 2005).

Finally, it should be acknowledged that this is a study of associations, even with the temporal relationships established by using 12-month follow-up data. Counter interpretations of some findings may be possible. Unmeasured constructs like trait coping may be unspecified variables driving some of the observed associations. Also, it is not possible to discern reciprocal causality between strategy use and outcomes. Nevertheless, the theoretical framework provided by the motivational theory of life-span development provides a parsimonious interpretation for study findings. A related point is that we did not measure change in use of strategies—rather our interest was in whether use of strategies at one time point had predictive value 12 months later.

Findings from this study may have important clinical utility for functionally compromised older adults as use of some compensatory strategies appears to indicate risk factors for future deterioration. Early identification of compensatory strategy use as a risk factor for further decline may help to forestall or mitigate deteriorations in quality of life for older adults and promote positive aging in place. Based on these findings, health care providers might want to routinely inquire not only about functional difficulty levels but also about the specific strategies used by older adults to address these difficulties in their homes. Change in the frequency of performing daily activities might signal the need to help older adults adapt different strategies that enable continued participation in activities. Reliance on help and assistive device use may signal the need to attend more closely to health conditions, fall risk, and other factors that may potentially contribute to functional declines and to help older adults prepare for future needs.

Some individuals may need assistance in learning compensatory strategies that support well-being over time. This study lends support to the importance of referring functionally vulnerable older adults to health professionals such as occupational therapists who can instruct in effective methods for performing valued activities differently. Previous research has shown that older adults, including the oldest old, can learn new methods of performing self-care and benefit from professional instruction (Gitlin et al., 2008).

Finally, this study shows that what older adults do on their own to adapt to and self-manage changes in their functional abilities have long-term implications for their well-being. Use of these compensatory strategies is a form of self-management that is rarely considered in clinical and social service settings. It is unclear how older adults choose compensatory strategies and at what point they do so in the experience of functional decline (Slagen-De Kort, Midden, & van Wagenberg, 1998; Wu et al., 2014). There may be a hierarchy of strategy use with older adults adapting a myriad of intraindividual or behavioral approaches (changes in method or frequency) initially, and then augmenting with other extraindividual strategies with further decline (devices or help) or exposure to knowledge and resources (Agree et al., 2004; Verbrugge & Sevak, 2002). Given the clear evidence that certain compensatory strategies optimize well-being and function and others do not, further research in this area should be encouraged and appropriate interventions be designed.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the statistical consultation of Dr. Walter Hauck. They gratefully thank the interviewing staff for their efforts and the study participants for their involvement.

L. N. Gitlin, principal investigator, developed study concept and design, and oversaw scientific integrity and interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. L. Winter served as project codirector, conducted the statistical analyses for this study, prepared statistical tables, and contributed to and edited manuscript drafts. I. H. Stanley assisted with literature reviews and critically edited manuscript drafts.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research reported in this article was supported by funds from the National Institute on Aging (Grant R01 AG13687) and the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant R24 MH074779).

Biographies

Laura N. Gitlin is professor in the Schools of Nursing and Medicine at Johns Hopkins University. She is also the director of the Center for Innovative Care in Aging that serves as a focal point for developing, testing, and implementing novel approaches to improving the health and well-being of older adults in their home and communities.

Laraine Winter is a research psychologist at the Philadelphia VA Medical Center. A social psychologist, she was a postdoctoral fellow in geropsychology at the Philadelphia Geriatric Center. Her research has focused on psychosocial interventions for veterans with traumatic brain injury and their families, families of those with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, and medical decision making concerning end of life care.

Ian H. Stanley is a clinical psychology doctoral student in the Department of Psychology at Florida State University. His research is focused on the scientific understanding and prevention of suicide across the lifespan, with an emphasis on older adults. At the time of the current study, he was a health educator in the Center for Innovative Care in Aging at Johns Hopkins University.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Agree EM, Freedman VA, Sengupta M. Factors influencing the use of mobility technology in community-based long-term care. Journal of Aging and Health. 2004;16:267–307. doi: 10.1177/0898264303262623. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1177/0898264303262623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk SS, Glass TA, Berkman LF. Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999;131:165–173. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00002. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-131-3-199908030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & The Merck Company Foundation. The state of health and aging in American 2007. Whitehouse Station, NJ: The Merck Company Foundation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger WH, Jr, Burns R, Messier SP, Applegate W, Rejeski WJ, Morgan T, Craven T. A randomized trial comparing aerobic exercise and resistance exercise with a health education program in older adults with knee osteoarthritis: The Fitness Arthritis and Seniors Trial (FAST) Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;227:25–31. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540250033028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske A, Bamonti PM, Nadorff MR, Petts RA, Sperry JA. Control strategies and suicidal ideation in older primary care patients with functional limitations. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2013;46:271–289. doi: 10.2190/PM.46.3.c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, Agree EM, Cornman JC, Spillman BC, Kasper JD. Reliability and validity of self-care and mobility accommodations measures in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. The Gerontologist. 2014;54:944–951. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt104. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Spillman BC, Agree EM, Mor V, Wallace RB, Wolf DA. Behavioral adaptation and late-life disability: A new spectrum for assessing public health impacts. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;104(2):e88–e94. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301687. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM, Baltes PB. Selection, optimization, and compensation as strategies of life management: Correlations with subjective indicators of successful aging. Psychology and Aging. 1998;13:531–543. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.4.531. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1037/0882-7974.13.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Bandeen-Roche K, Williamson JD, Prasada-Rao P, Chee E, Tepper S, Rubin GS. Functional decline in older adults: Expanding methods of ascertainment. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 1996;51:M206–M214. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51a.5.m206. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gerona/51A.5.M206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gignac MAM, Cott C, Badley EM. Adaptation to chronic illness and disability and its relationship to perceptions of independence and dependence. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;50:P362–P372. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.6.p362. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/55.6.P362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Hauck WW, Dennis MP, Schulz R. Depressive symptoms in African American and White older adults with functional difficulty: The role of control strategies. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:1023–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01224.x. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Hauck WW, Dennis MP, Winter L, Hodgson N, Schinfeld S. Long-term effect on mortality of a home intervention that reduces functional difficulties in older adults: Results from a randomized trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:476–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02147.x. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Hauck WW, Winter L, Dennis MP, Schulz R. Effect of an in-home occupational and physical therapy intervention on reducing mortality in functionally vulnerable elders: Preliminary findings. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:950–955. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00733.x. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Szanton SL, Hodgson NA. It’s complicated—but doable: The right supports can enable elders with complex conditions to successfully age in community [Special issue on Aging in Community] Generations. 2014;37:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Corcoran M, Schinfeld S, Hauck WW. A randomized trial of a multi-component home intervention to reduce functional difficulties in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:809–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00703.x. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hauck W. Variation in response to a home intervention to support daily function by age, race, sex, and education. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2008;63:745–750. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.7.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J, Wrosch C, Schulz R. A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychological Review. 2010;117:32–60. doi: 10.1037/a0017668. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1037/a0017668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoenig H, Ganesh SP, Taylor DH, Jr, Pieper C, Guralnik J, Fried LP. Lower extremity physical performance and use of compensatory strategies for mobility. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:262–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00588.x. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz A, Brennan M, Reinhardt JP, MacMillan T. The impact of assistive device use on disability and depression among older adults with age-related vision impairments. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2006;61:S274–S280. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.5.s274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffee MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincade-Norburn JE, Bernard SL, Konrad TR, Woomert A, DeFreise GH, Kalsbeek WD, Ory MG. Self-care and assistance from others in coping with functional status limitations among a national sample of older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1995;50:S101–S109. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.2.s101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody E. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenze EJ, Rogers JC, Martire L, Mulsant BH, Rollman BL, Dew MA, Reynolds CF., III The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability: A review of the literature and prospectus for future research. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9:113–135. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00019442-200105000-00004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann WC, Hurren D, Tomita M, Charvat BA. The relationship of functional independence to assistive device use of elderly persons living at home. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1995;14:225–247. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1177/073346489501400206. [Google Scholar]

- Manton KG, Corder LS, Stallard E. Estimates of change in chronic disability and institutional incidence and prevalence rates in the U.S. elder population from the 1982, 1984, and 1989 National Long Term Care Survey. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 1993;48:S153–S166. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.s153. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronj/48.4.S153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek KD, Popejoy L, Petroski G, Mehr D, Rantz M, Lin WC. Clinical outcomes of aging in place. Nursing Research. 2005;54:202–211. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min LC, Elliott MN, Wenger NS, Saliba D. Higher vulnerable elders survey scores predict death and functional decline in vulnerable older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:507–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00615.x. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Schooler C. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:2–21. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2136319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Heckhausen J. A life span model of successful aging. American Psychologist. 1996;51:702–714. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.51.7.702. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.51.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsick EM, Lafferty ME, Phillips CL, Mendes de Leon CF, Kasl SV, Seeman TE, Lemke JH. Risk due to inactivity in physically capable older adults. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:1443–1450. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.10.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slagen-De Kort YAW, Midden CJH, van Wagenberg AF. Predictors of the adaptive problem-solving of older persons in their homes. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 1998;18:187–197. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1006/jevp.1998.0083. [Google Scholar]

- Tabbarah M, Silverstein M, Seeman T. A health and demographic profile of noninstitutionalized older Americans residing in environments with home modifications. Journal of Aging and Health. 2000;12:204–228. doi: 10.1177/089826430001200204. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/089826430001200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, Sevak P. Use, type, and efficacy of assistance for disability. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:S366–S379. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s366. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.6.S366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl HW, Oswald F, Zimprich D. Everyday competence in visually impaired older adults: A case for person-environment perspectives. The Gerontologist. 1999;39:140–149. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.2.140. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geront/39.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, Schulz R. Activity restriction and prior relationship history as contributors to mental health outcomes among middle-aged and older spousal caregivers. Health Psychology. 1998;17:152–162. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.2.152. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.17.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinsky FD, Miller DK, Andresen EM, Malmstom TK, Miller JP. Further evidence for the importance of subclinical functional limitation and subclinical disability assessment in gerontology and geriatrics. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;60:S146–S151. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.s146. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/geronb/60.3.S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrosch C, Schulz R, Heckhausen J. Health stresses and depressive symptomatology in the elderly: The importance of health engagement control strategies. Health Psychology. 2002;21:340–348. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.340. Retrieved from http://dx.doi. org/10.1037/0278-6133.21.4.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y-H, Cristancho-Lacroix V, Fassert C, Faucounau V, de Rotrou J, Rigaud A-S. The attitudes and perceptions of older adults with mild cognitive impairment toward an assistive robot. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0733464813515092. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/0733464813515092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]