Abstract

Objective: This article presents the results of complementary research studies on the behaviors of hospital clinicians in asking clinical questions and the relationship between asking of questions, outcome of information searches, and success in problem solving.

Methods: Triangulation in research methods—a combination of mailed questionnaires, interviews, and a randomized controlled study—was employed to provide complementary views of the research problems under study.

Results: The survey and interviews found that clinical problems (concerned mainly with therapy and equipment or technology) were expressed as statements rather than questions (average number of concepts = 1.7), that only slightly more than half (higher for doctors) of problems could be solved, and that the majority of clinical questions were not well formed. An educational workshop however improved clinicians' formulation of questions, but the use of structured prompting was found to improve building of hypotheses in the doctors' group without training. The workshop also improved satisfaction with the obtained information and success in problem solving. Nonetheless, for both the experimental and control groups, more structured and complete questions or statements did not mean higher success rates in problem solving or higher satisfaction with obtained information.

Conclusion: The triangulation methods have gathered complementary evidence to reject the hypothesis that building well-structured clinical questions would mean higher satisfaction with obtained information and higher success in problem solving.

INTRODUCTION

The evidence-based approach in medicine (EBM) advocates learning through problem-based inquiry. The success of the inquiry hinges initially on the clinical questions posed, the information resources used, and the skills used in applying these resources. Articulating or translating the problem or the clinical situation on hand into a well-built clinical question is the first and fundamental step in practicing EBM.

The clinical decision-making process is complex and nonlinear [1]. Early hypothesis generation and verbalization (thinking aloud) in problem solving play crucial roles in medical decision making and partly guide subsequent data collection [2].

According to Richardson [3], a well-built clinical question has a focus and a four-part anatomy: the patient or problem, the intervention (e.g., a drug prescription) or exposure (e.g., a cause for a disease), the comparison intervention or exposure, and the clinical outcomes. Sackett [4] suggests that clinicians having trouble articulating questions the first time can express them out loud or write down explicit components in four columns, one for each element of the question.

Forming the question is closely related to the ability to search for best evidence, as the more focused the question, the more relevant and specific the search will be. Sackett [5] believes that well-formed questions support clinical practice in helping clinicians focus directly on the relevant evidence and the new information that they need. The question will suggest search strategies and the forms that useful answers might take. It also helps in communicating with other colleagues and in teaching.

With the above analogy, it is reasonable to hypothesize that asking well-formed questions would bring about higher satisfaction with obtained information and higher success in problem solving. No definitive studies, however, can demonstrate the aforementioned effects of asking well-structured clinical questions. Only personal cases have been reported [6].

LITERATURE REVIEW

Studies reported in the literature looked at the effectiveness of the information-seeking processes and behaviors of physicians and general practitioners in their work setting: their rate and nature of asking questions, sources used, and success in problem solving.

Asking clinical questions

All studies found that clinical questions arose on a daily basis in the course of patient care. The number of questions generated varied greatly, probably due to the different methodologies and the different settings of the clinical practices. Covell [7] found that the 47 primary care physicians had asked 0.66 questions per patient, while Osheroff found that 24 doctors at a university-based hospital had 5.77 questions per patient encounter [8].

Many questions were about treatment and, specifically, about drugs. About 33% of the questions in Covell's study [9] were about treatment, 25% about diagnosis, and 14% about drugs. Drug-related information was needed most: 38% in a study by Williamson [10] and 64% in Woolf's investigation in an academic center [11]. Drug or therapy queries captured in a study of medical doctors in the National Health Service, United Kingdom [12], amounted to 35% of total reported queries. Doctors' questions tended to be complex and multidimensional, and they related particular patients' history to medical knowledge [13].

Success in solving clinical problems

Only a few studies have produced results about success in problem solving. Many of the clinical questions were never answered. With the 27 general practitioners in Australia, the success rate was 79% [14]. Timpka's study [15] of 84 general practitioners produced a much lower rate of 51%. Gorman [16] found that out of 295 questions generated by 49 doctors, only 33% of the problems were pursued by doctors and the answers to less than 25% were found. Ely's latest study [17] of 103 family doctors showed a similar pattern of deferring the search for information. Of the total of 1,101 questions posed, 67% were not immediately pursued, and, of those that were pursued, 80% were answered.

Research methodology

Widely varying methodologies made comparability and cumulative research difficult. Out of the seventeen original studies on the information needs of physicians that were reviewed, five used questionnaires [18–22], five used interviewing alone or as a supplementary method [23–27], and three used observation [28–30]. The results were not cumulative due to differences in the definitions and categorizations of the needs and different methodologies (observation, interviews, interviews with structured questionnaire).

Observational methods have been demonstrated to elicit needs that doctors do not identify themselves [31]. Of interest to information scientists are the conflicting answers given by doctors during the questionnaire stage and, afterward, during the interview [32]. Combined methodologies of interviews to supplement structured questionnaires seem to have produced more in-depth understanding of doctors' information needs and are the preferred method to date [33].

The generalizability of the research done so far on clinicians in hospitals has been even less certain. The majority of study populations reported on in the literature have been general practitioners and family physicians in the primary care setting, in doctors' offices and clinics. Very few investigations have been carried out in the hospital setting. The only “sizeable” study of clinicians in the hospital setting was conducted in Spain [34] and produced quite different results. Using structured questionnaires and the critical incident technique, researchers found that physicians needed information on a day-to-day basis.

An important factor to consider is the more critical nature of the clinical setting in hospitals. Primary care doctors are more likely to resort to referrals to specialists and deferral of decisions as coping strategies. Secondary care givers might have to either pursue searching or “make do” more frequently, especially when critical decisions have to be made in the emergency room and other departments or specialties of the hospitals. It is doubtful that the findings in reported literature can be universally applied to the secondary care setting in hospitals.

After reviewing the literature, little evidence suggests that the evidence-based approach to these processes actually leads to better evidence and faster search processes and helps solve clinical problems. Research into the area of hypothesis building and success in information seeking by hospital clinicians is the primary focus of this article.

OBJECTIVE

This article presents the results of complementary research studies on the behaviors of hospital clinicians in asking clinical questions and the relationship between asking of questions, outcomes of information searches, and success in problem solving. It intends to show that the evidence-based approach in question formulation is effective in achieving the desired search outcomes: satisfaction with obtained information and success in problem solving.

METHODS

Triangulation in research methods—a combination of mailed questionnaires, interviews, and a randomized controlled study—was employed by the author to provide complementary views of the information-seeking behaviors of hospital clinicians.

Quantitative survey

A quantitative study using the critical incident technique was used to map the information environment and to extract the type of problems or questions asked on a daily basis, the information needed for the problem in hand, and the search outcomes. The survey instrument was developed using terminology derived from the literature and the results of nominal groups conducted prior to the setting of the questionnaire [35]. Stratified random sampling was employed to increase precision [36], to ensure a wide spectrum of users' professions and ranks, and to ensure that the types of hospitals (e.g., acute or rehabilitation) were adequately represented in the sample. The sampling frame was a complete, computerized list of about 30,000 health care professionals employed by 44 public hospitals in Hong Kong, sorted by user group, rank, and type of hospital (probability of selection 5.32%, sampling error 2.4%). A total of 1,565 samples were drawn, and the response rate was 52%. The response rate for question one (to solicit the clinical question) was 31.4%.

Telephone or personal interviews

Subsequent to the survey, structured interviews were conducted to complement the survey. A total of fifty clinicians and three librarians volunteered to be interviewed. Methods were employed to strengthen the validity and reliability. The interviews were conducted by three fellow librarians, not by the investigator. The interviews were taped, translated from Chinese, recorded as questions and answers, and stored in AskSam. The draft interview reports were circulated to the other two interviewers not conducting the interview under review for verification of the translations. The qualitative study gave deeper meaning to the investigation of information seeking and helped explain the survey results. Together, the problems or barriers could be better identified.

The results of the interviews were dovetailed into the quantitative findings and helped explain behaviors and relationships (or the lack of these) between variables. The model depicted low success in information seeking and the lack of a relationship between use of electronic information services (EIS) and success in problem solving. The author assumed that the identified barriers (personal characteristics, information environment, work environment factors) were responsible for the weak correlation between the clinical questions, the search for EIS, and success in problem solving.

Randomized controlled study

An experiment using three-hour educational workshops was designed to address the barriers and enable conditions identified in the survey and interviews. Before the experiment, the information environment was improved with increased availability of online full-text information. The relationships between an educational intervention and the information-seeking skills, knowledge, and attitudes (personal characteristics) of users' success in problem solving and satisfaction with EIS use were explored.

The target population was clinicians who responded to training circulars and wanted to enroll in a searching workshop, ensuring that the target population was homogeneous in characteristics.

To ensure external validity, the “posttest-only control group design” was chosen [37]. Pretests were regarded as unnecessary when random assignment was used. As the experimental group was likely to learn from the pretest and change their answers accordingly, Sproull [38] suggested control of the testing factor by avoiding the pretest.

A total of 800 randomly assigned subjects (stratified randomization by profession) were recruited. Analyses of the evaluation questionnaires were based on comparisons of the experimental group after training and the control group without training. Blinding was implemented for both the subjects and the workshop tutors. Detailed methodology of the experimental design was given in a separate article [39].

RESULTS

Clinical questions help focus the clinical inquiry. Clinical questions reported in the survey were categorized and analyzed by components, according to the evidence-based approach: “background” questions asking general knowledge of a particular disorder and “foreground” questions bringing the patient's diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and so on to the fore. According to Sackett, the proportion of foreground questions over background questions increases with experience and responsibility of the clinician [40].

Background questions have two components: a question root (what, when, etc.) and a disorder or aspects of it. Clinical foreground questions should have a number of components: the patient or problem, the intervention, the comparison intervention, and the clinical outcomes. The more specific the question, the easier it is to focus and effectively track down best evidence to answer day-to-day problems [41].

Results from survey and interviews

The first part of the survey questionnaire focused on studying the question-asking patterns of clinicians by posing an open-ended, free-text question. Altogether, 254 responses (out of 804 responses) specifying clinical questions or problems were returned. The questionnaire asked respondents to describe one occasion (in the form of a statement, question, or topic) in the last 7 days when they needed information for patient care, personal study, research, or teaching. The profiles from respondents who had described a question or problem were compared with those who left it blank. It was found that those describing a question or problem tended to have more experience and higher educational qualifications. Proportionately, more doctors returned a clinical question, and they reported longer reading hours. With this result in view, it could be reasonably assumed that such reported questions had been returned from information users with more experience, higher educational levels, and rank. The following analyses concentrated on the responses that reported a clinical question or problem.

In terms of the absolute number of questions posed, 50% of them originated from nurses, about 25% from doctors, and the remainder from allied health professionals. When responses by rank were considered, it was found that a higher proportion of senior doctors and nurses returned clinical rather than other types of questions. Fifty-seven percent of doctors' questions and 80% nurses' clinical problems originated from senior ranks.

The contents of the questions or problems were analyzed by two coders who were professional librarians. The codes were then counterchecked by the author. The questions were classified according to their content: broadly clinical or managerial in nature. Then the clinical questions or problems were compared with and categorized according to the components (the patient or problem, intervention, outcomes) of the structured clinical question.

Nature of question or problem reported

Seventy-five percent of the reported topics or questions were clinical in nature, 19% were managerial, 3% related to health care, and 3% were for teaching and education. Among the questions or topics posed by doctors, 91% were clinical in nature, compared with 69% by nurses and 82% by allied health professionals. More nurses (25%) than others reported managerial problems.

Professional ranks having higher than average clinical questions were medical officers, pharmacists, senior enrolled nurses or midwives, physiotherapists, and consultant doctors. At subsequent interviews with some respondents, reasons given for the low responses for other groups of staff—including interns, midwives or enrolled nurses, radiographers or radiotherapists, and dispensers—were: “I seldom have the need to search for information for my day-to-day clinical duties” (nurse interviewee no. 6, June 2 1999) and “I have not been looking for information for a long time since graduation because work was really busy and routine” (radiographer interviewee no. 38, June 11 1999).

The form of query (in question or statement form)

The questions or problems presented by respondents were then classified into question or statement form. Even though the actual example in the questionnaire was deliberately provided in the form of a clinical question, about 69% of responses expressed needed information in the form of a statement, instead of a question. Subsequent interviews confirmed that all but a few interviewees expressed their problems spontaneously and verbally in the form of statements rather than in the form of questions, if they were not prompted further.

When broken down by rank and profession, selective groups of staff—radiographers, interns (both 67%), and pharmacists (60%)—had a higher tendency to present their problems as questions, compared with the average of only 31% of responses. Senior doctors had a lower tendency to use question format (18%) than medical officers (50%), interns (67%), and pharmacists (60%). The pattern was similar with nurses: more junior nurses—senior enrolled nurses, enrolled nurses, midwives (46%)—than senior nurses—registered nurses (38%) and chief nursing officers/ward managers (35%)—tended to describe their problem in question form rather than statement form.

Conceptual components of the clinical problem

An analysis and categorization of the content of the clinical problems, topics, or questions cited by respondents showed that the average number of components in the problems posed by respondents was 1.7. Problems with a single concept amounted to 41% of the posed problems. Statements or questions from interns, pharmacists, and consultants had a higher than average number (2.5, 2.0, and 2.0, respectively) of components.

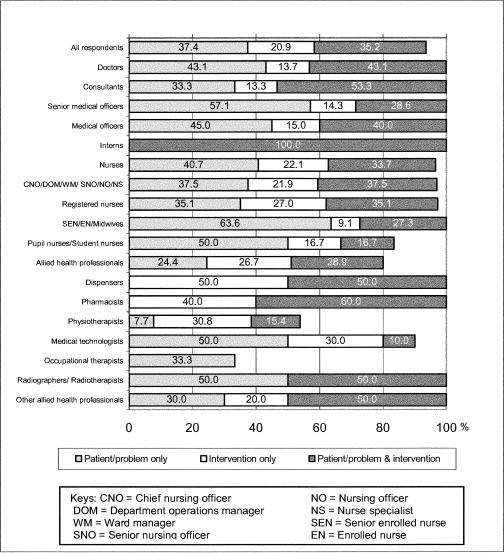

Thirty-seven percent of the problems described only the patient or problem/disease, which were background questions. When analyzed by rank, background questions containing patients' problems/diseases were made by 33% of the consultants, 57% of senior medical officers (SMO), and 45% of medical officers (MO). For nurses, 38% of chief nursing officers or ward managers, as compared with 50% of student nurses, asked background questions. Figure 1 shows that the proportion of foreground questions compared with background questions increased with rank and responsibility. This increase was broadly true for both doctors and nursing groups. Interns were an exception, however, due to limited data (only two questions were returned by them). Very few statements or questions contained the outcomes components (7%), and only 2% contained all the elements of a well-constructed clinical question. No questions or statements in the doctors' group had all of the elements.

Figure 1.

Conceptual components of the clinical problem or question

Representation of a clinical problem is a complex process in which a number of issues—ease of expression of the clinical problem, the language used (Chinese versus English), time in hand, and so on—play a part in affecting the pattern of question formulation and reporting in the survey. The analyses of the clinical questions or problems supplied by respondents showed that: first, the majority of the problems were presented as statements; second, the number of concepts in clinical questions was lower than 2 (average = 1.7); and third, over 40% of the problems represented single concepts, of which 37% were background questions.

These indications showed the clinicians' ability to ask or report well-structured and answerable questions had room for improvement. It was also found during the interviews with librarians that they thought that users had problems breaking the questions into distinct searchable concepts (librarian interviewee no. 53, 30 December 1999).

Types of clinical problems or questions asked

No standard taxonomy of clinicians' information needs had been defined to date. The content of the needed information and the purpose of the information need were analyzed from respondents' answers to questions 2 to 4 of the survey. The question or statement was analyzed in two ways: the medical knowledge organized by types of clinical studies found in the literature, especially those on EBM (i.e., etiology, diagnosis, therapy, prognosis, etc.), and the purpose of raising the problem or question. The latter was established by using the results gathered at the nominal groups conducted before the survey.

It was found that problems with therapy (including both drug therapy and interventions or therapy) occurred most frequently (40% of the problems overall) and in all clinician groups of doctors (46%), nurses (34%), and allied health professionals (50%). The next highest proportion of questions related to equipment or technology and was posed by doctors (34%) and nurses (30%). A lower proportion of doctors (7%) and nurses (6%) needed diagnosis information. Allied health professionals seemed to have required more diagnosis information (18%). Prognosis was needed by doctors alone, and etiology and patient management were needed by nurses.

Among nurses, equipment or technology information was needed most (30% of clinical questions): “I wanted to find out more about signs and symptoms of my stroke patient,” as expressed by a nurse (interviewee no. 9, June 2 1999). For them, patient-management information (28%) was next.

Doctors' most frequent problems or questions related to equipment or technology (34%) and therapy (including drug therapy, 46%). With allied health professionals, the clinical problems related more to drug therapy (32%) and equipment or technology (23%). Pharmacists more than dispensers had to ask clinical questions: “Most clinical problems would be passed to Pharmacists, whereas Dispensers would handle the day-to-day operations and routines in order to avoid conflict of responsibilities” (interviewee no. 15, June 4 1999).

Occasions when and where clinical problems or questions arose

The most frequently occurring occasions when the problem or question arose were when respondents were deciding on treatment options (29%), had been asked by a supervisor or colleague (26%), and were diagnosing patients (19%).

In the majority of cases, the most needed information was clinical research evidence (56%) and clinical guidelines and protocols (51%). They were needed in many clinical situations: while making the ward rounds, diagnosing patients, deciding on treatment options, and planning the discharge of patients. Such types of information were also needed in professional, nonclinical situations: when responding to supervisors, colleagues, or subordinates; preparing lectures; reviewing; and developing services.

The clinical questions arose mostly while the respondents were in their departments or offices (43%) or their wards (42%). On very few occasions, information needs arose at home (6%), and, if they did, the purpose was for doing homework.

Respondents' success in solving the problems or questions that arose

The questionnaire asked if the problem or question that arose in the last seven days was solved. It was found that among the reported questions, the success rate in solving them was not high.

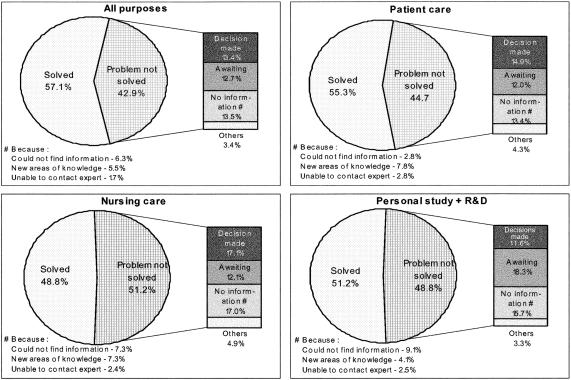

Figure 2 shows that a total of 57% of the respondents could solve the problem or question on hand and the rest could not. Thirteen percent of the respondents did not solve the problem and made a decision anyway due to urgency. Six percent could not find the information, and 4% were awaiting published materials. Six percent said that their problem covered new areas of knowledge, and 8% of respondents felt research was needed for the problem.

Figure 2.

Proportion of problems solved

When broken down by purpose, problem-solving rates were marginally lower for patient care and nursing care. Fifty-five percent (compared with the average of 57%) of the respondents who had a problem for patient care and 49% of those who had a problem for nursing care could not solve their problems in the last 7 days. Fifteen percent and 17%, respectively, made a decision anyway without the information due to urgency. The remaining cases were still awaiting publications (4% and 2%, respectively) or research to be done (6% and 9%, respectively) for the question or problem on hand. Those with nursing-care problems seemed to have more difficulty with finding the information than those with patient-care problems: 7% of respondents with nursing-care problems compared with 3% of respondents with patient-care problems could not find information (Figure 2).

Analysis was then carried out based on groups of doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals for solving problems of patient care. The success rate for doctors in solving the problems as a whole (77%) was higher than that of nurses (52%) and allied health professionals (52%). If only patient-care or nursing-care problems were considered, the success rate for patient-care or nursing-care problem solving was 73% (compared with 48% for nurses and 51% for allied health professionals).

Generally speaking, success rates for problem solving as a whole for doctors (77%) and nurses (52%) were marginally higher than problem solving related to patient-care or nursing-care problems for doctors (73%) and nurses (48%). For doctors, 27% of patient-care problems had not been solved, while nurses and allied health professionals had a higher proportion of unsolved clinical problems (52% and 49%, respectively).

Association between success in problem solving and the question or problem asked

Investigations of the asked question or problem were approached from three aspects: the form of query (statement or question form), the number of concepts in the question, and the presence (or absence) of a four-part anatomy in a clinical question.

When the success in problem solving was compared with the form of query (i.e., whether the problem was presented as a question or statement), no relationship was found. For problems presented in question form, 53% were solved. Of those presented as a statement, 60% were solved. No significant difference was found in problem solving, whether the problem was presented as a question or statement (P = 0.289).

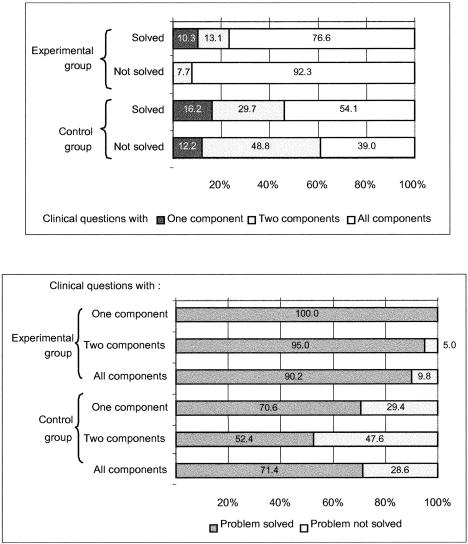

When the number of concepts presented in the question or problem asked by respondents was compared with success or failure in solving the problem, no relationship was found between the two (Figure 3). For single-concept problems, 63% of them had been solved, while, for problems with 2 concepts, only 52% had been solved. For problems with 3 concepts, however, 61% had been solved. There was no significant difference in success rates between problems solved or not solved (P = 0.348). The results showed that the specificity in the question or problem had no relationship with success in problem solving.

Figure 3.

Problem-solving and structure of problem posed

The questions or problems were broken down into components of structured clinical questions as advocated in EBM (i.e., categorizing the elements of a problem into patient or problem component, intervention component, outcomes component, and their combinations). The questions or problems were grouped according to how the respondents presented them. For problems with only a patient or problem component, 55% had been solved (compared with the average of 58%). For problems with an intervention component only, 76% had been solved. For questions with 2 or more components of patient or problem and intervention, 52% had been solved.

The above analyses revealed that the majority of the self-reported clinical questions were not well built. Forty-two percent of the problems or questions had only a single concept, and only 2% of the questions or problems contained all the elements of a well-structured question. Success in problem solving was just over 50%. The significance tests showed no correlation between success in problem solving and specificity of the clinical question. The success rates were better with problems of interventions but were slightly lower than average for background questions and those with both components (intervention and patient or problem). It should be noted that there was only one clinical question on outcome, and the 100% failure rate for outcome problems was due to insufficient data.

Success rates were not associated with the form of query (statement or question), the structure of the problem, or the specificity of the problem (with single or multiple concepts). Problem-based question format, structured questions, or more specific problems did not mean higher success rates in problem solving. The hypothesis that success in problem solving is related to the building of well-structured clinical questions could not be supported in the study population.

Results from the randomized controlled trial

Clinicians were requested to state a clinical problem in an open question in question 2 of the questionnaire before or after the workshop, depending on the group to which they were assigned. Furthermore, clinicians were prompted through the provision of a structured frame in question 3 to input the key elements of the clinical question. The stated clinical problems were then analyzed by coders for their form (question or statement) and the number of concepts contained in each question or problem. Independent, blinded evaluators were recruited for categorizing the clinical questions in the questionnaire by all clinicians in experimental and control groups. They were not aware of who had received training when they analyzed the structure of clinical questions.

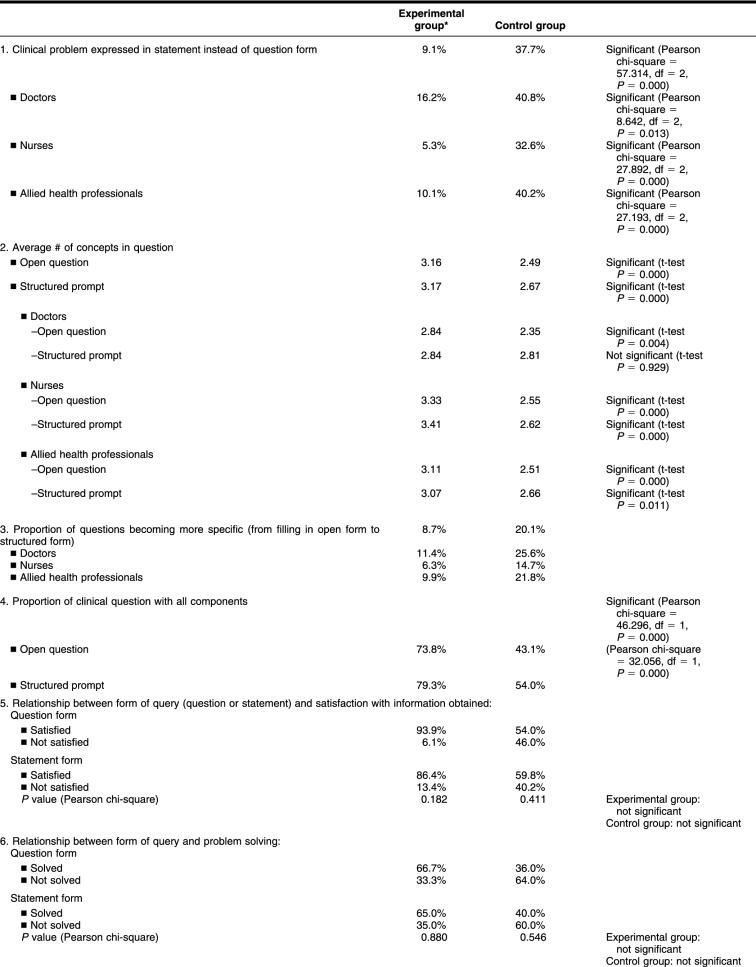

The form of query (statement or question)

As a whole, training was found to improve clinical question formulation. As shown in Table 1, the use of statements to express a clinical problem or topic by the experimental group was significantly lower (9%) than those in the control group without training (38%; P = 0.000). This comparison was true also of doctors (16% of statements in the experimental group compared with 41% in the control group; P = 0.013), nurses (5% compared with 33%; P = 0.000), and allied health professionals (10% compared with 40%; P = 0.000) (Table 1, section 1).

Table 1 Clinical question formulation

Conceptual components in the clinical question

There was also a significant difference (P = 0.000) between the experimental group and the control group in the average number of concepts in their clinical questions. For the experimental group, the average number of concepts in their questions was 3.16 for the open question and 3.17 for the structured frame. For those without training, the average numbers dropped to 2.49 and 2.67, respectively. The differences were significant for individual user groups (Table 1, section 2).

The only case with no significant difference between the experimental group and the control group was when doctors in the control group responded with the same number of concepts as the experimental group (2.81 and 2.84, respectively; P = 0.929) when subject to structured prompting in question 3. This similarity indicated that doctors in the control group were responsive to prompting in the written questionnaire even without training. The increase in the number of concepts when clinicians moved from question 2 to question 3 was more easily seen in the doctors' group who had not attended training, and the average number of concepts for this group improved from 2.35 to 2.81 (Table 1, section 2).

Completeness of the clinical question

Twenty percent of the clinicians who had not received training became more specific in their descriptions of the clinical problem when answering in a prompted frame than they had been in an open-question format. Only 9% of the clinicians in the experimental group had more specific descriptions when prompted by a structured frame in question 3. The questionnaire with the structured frames seemed to have improved specificity of concept breakdown, especially for the group without training. This improvement was true of doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals (Table 1, section 3).

The problems in question 2 and question 3 were then coded according to whether they had all the components of the clinical question. For the open question 2, a higher proportion of clinicians from the experimental group (74%) than the control group (43%, P = 0.000) were able to describe clinical questions with all the three components. This difference was equally true for doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals. Improvement was seen in the experimental group when they answered the structured, framed question (question 3), which prompted for all major components of a clinical question. The performance of the group without training was compared to see when they gave complete clinical questions in question 2 and question 3. A higher percentage of the control group was able to describe a complete clinical question in question 3 (54%) than they could in question 2 (43%) (Table 1, section 4).

Training was found to provide simulated situations and improve clinicians' question formulation. On the other hand, the use of structured prompting was found to improve question formulation (in complete descriptions) even without training.

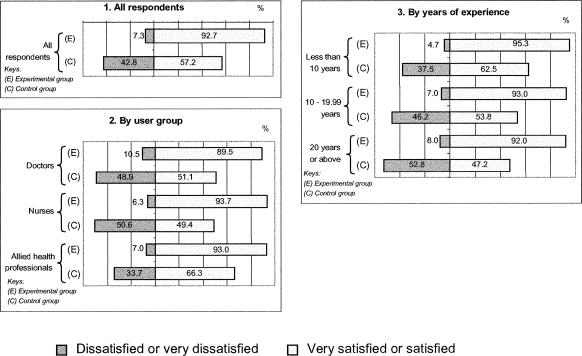

Satisfaction with obtained information

The satisfaction rating with the obtained information for the experimental group was 93%, much higher than for the control group (57%). Clinicians who received training were 9.517 times more likely to be satisfied with the obtained information than those who had not been trained (i.e., odds ratio = 9.517). The number needed to train (NNT) was 3, meaning that 3 users were needed to be trained before 1 additional user was satisfied with the obtained information (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Satisfaction with information obtained from searching

Form of query and satisfaction with obtained information

Although the educational intervention was found to change the form of query from statement to question and to influence satisfaction with obtained information, the change of query from statement to question form did not affect satisfaction with obtained information in both the experimental group (P = 0.182) and the control group (P = 0.411) (Table 1, section 5).

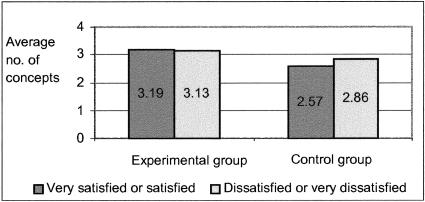

Completeness of clinical question and satisfaction with information search

The author put the relationship between the specificity and completeness of clinical questions and satisfaction with obtained information to the test. It was hypothesized that the higher the number of concepts in the clinical question (the better the focus), the more satisfied a user would be with the information obtained from searching. The number of concepts in the clinical question had no effect on satisfaction. Of those in the experimental group who were satisfied or not satisfied with the information obtained, the number of concepts was 3.19 and 3.13, respectively (P = 0.806). There was no relationship between the specificity and the satisfaction with information obtained. The same was true of the control group in that those who were satisfied or not had similar numbers of concepts in their clinical questions (mean = 2.57, mean = 2.86, respectively, P = 0.108) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Specificity of clinical question with satisfaction with information obtained

The form of query and success in problem solving

The results from the randomized controlled trial showed that the educational workshop reduced the use of statements in formulating a clinical problem. A significance test, however, revealed that success in problem solving was not related to the form (statement or question) in which the clinical problem was expressed for both the experimental group and the control group. In the former case, there was no significant difference (P = 0.880) when 67% of the problems in question form were solved, while 65% of the problems in statement form were solved. The same was true of the control group (P = 0.546) (Table 1, section 6).

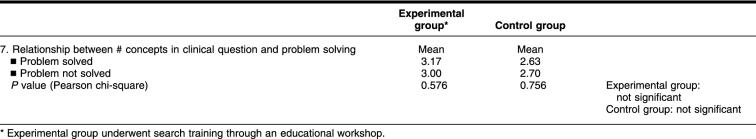

Number of concepts in clinical question and success in problem solving

As shown above, the educational intervention improved specificity of the posed problem. Nonetheless, success in problem solving was not associated with specificity in the clinical question (in terms of number of component concepts). For the experimental group, the number of concepts in the clinical question averaged three or above, while the number of concepts in the control group was more than two. For the experimental group, there was no significant difference (P = 0.576) in the number of concepts between those who could solve the problem (mean = 3.17) and those who could not (mean = 3.00). The control group was found to be the same (P = 0.756), indicating that the specificity of the clinical problem played no part in solving it successfully for either the experimental group or the control group (Table 1, section 7).

Completeness in the clinical question (i.e., question comprising all elements of clinical question) did not lead to higher success rates in problem solving, either. For the experimental group who had solved their clinical problem, 77% expressed problems containing all components of a clinical question, while the rest had only 1 or 2 components. For the experimental group who did not solve their problem, 92% of them had complete questions and the rest did not. This result suggested that complete clinical questions did not bring about higher success rates in problem solving (Figure 3).

The findings from the trial were consistent with the results of the survey research. There was no relationship between problem solving and the specificity and structure of the clinical question. In the same study, respondents attributed the failure to solve problems to their inability to find information.

Success in problem solving

The findings from the experiment confirm or complement those from the survey research. They confirm the earlier rejection of the hypothesis after the survey that success in problem solving was related to the specificity and structure of the posed problem, although the educational workshop was found to improve problem formulation and specificity and structure of clinical questions. Success in problem solving was not the result of expressing the problem in question form, having higher specificity, or having a more complete structure for the clinical problem.

In addition, satisfaction with the obtained information was not related to form of query (question or statement) or the specificity and structure of the clinical problem. The evidence-based approach of treating question formulation as the first essential step in searching the evidence and solving a clinical problem has not been supported by the current study.

Contrary to the findings in the earlier survey, the experiment suggests that success in problem solving was affected by the information sources used (EIS rather than print or expert). Success in problem solving was not related to the skills and knowledge in searching (as represented in search scores), although training raised the awareness of information sources and enhanced the use of primary and secondary resources. The educational effects on the awareness and skills in searching have eroded after twelve months. However, the educational workshop improved the rate of success in problem solving. It could be concluded with a fair degree of certainty that the rate of success in problem solving would be enhanced by reducing the barriers to EIS use through educational intervention and creation of enabling conditions in the information environment [42].

DISCUSSION

Although question building is regarded in the evidence-based approach as an important first step, this study rejects the hypothesis that success in problem solving is related to the form of query and specificity and structure of the posed clinical question. A number of hidden causes could have worked in between forming of the question and final resolution of the problem, including the background and experience of the clinician in verbalizing, identifying, and defining the clinical problem. The study fails to establish any relationship between question structure and success.

The use of a self-administered survey to solicit clinical questions might not be the best research method for busy clinicians at hospitals. The cited questions were derived from memory. Although the published literature had no information at all as to the quantity and frequency of questions generated in hospital care on a daily basis, the low response to the first question (31.4%) on clinical problems partly testified to the weakness of using self-reported questionnaires alone. However, it was considered the only feasible way; observation was tried initially, but clinicians were not amenable to investigative questions in busy clinical areas such as wards. Also, the survey instrument of four pages was fairly long, leading to missing data in some cases.

Using survey research methods, response on clinical questions is low. As the formulation of clinical hypotheses is believed to constitute an important first step in evidence-based practice leading to better evidence and patient care, more research is needed on the best method to elicit and capture the clinical question behavior of clinicians in hospital wards on a day-to-day basis.

It would be interesting to see if the use of the “thinking aloud” method that has been successfully employed in the study of medical decision making by medical students might work in a clinical setting. Another method worthy of further pursuit is the employment of observation followed by interviews, something which the author found futile in hospital wards on initial investigation, yet which has been shown by other authors to yield satisfactory results in the offices of primary care physicians.

Another related finding was that hypotheses for hospital clinicians in Hong Kong were expressed as statements rather than questions. A review of the questionnaire did not show any obvious flaws, because an example of the expected answer form was given in the questionnaire. The author wonders if the pattern in the use of statements for expressing a clinical problem might be due to the syntax of the Chinese language. To what extent this is true of real question-asking behavior and the likely difference it would make in problem solving would be interesting areas for future research.

One interesting and related finding was that, even though clinical question formulation was found to have no association with problem solving or satisfaction with the obtained information, the use of a structured frame in the questionnaire to prompt clinicians when completing the clinical question was successful in improving the specificity and conceptual breakdown of the clinical problems. This improvement was the case regardless of whether clinicians had attended the workshop. Advocates of evidence-based practice regard question formulation as important and useful for focusing thought during critical appraisal and application of evidence. The use of structured prompting before searching would facilitate clinical problem formulation without training and should be considered in system or interface developments.

The research reported here showed that it is feasible in library and information science to carry out triangulation studies and produce definitive findings. The randomized controlled trial method was used to establish cause-and-effect relationships, and it can be said with certainty, despite the low response from the earlier survey research, that structured questions or more specific problems did not lead to higher success rates in problem solving or higher satisfaction with obtained information for both the experimental and the control groups. The educational workshop, however, has been shown to improve clinicians' question formulation, but the use of structured prompting was found to improve hypothesis building regardless of training. The trial attributed success in problem solving to other factors [43], but these factors were beyond the scope of this article.

The conduct of a randomized controlled trial requires resources, especially in the randomized allocation of subjects and in recruiting, coordinating, and communicating with potential subjects. The current trial of 800 subjects held over 1 month affected resources in the library setting. In the future, more cooperation and coordination in library and information science research, such as the use of a multicenter or even a cross-country approach in conducting such trials, may turn out to be a viable alternative, spreading the load and adding reliability to the results.

Despite the negative findings that clinical question formulation did not lead to satisfaction with obtained information or problem solving, the studies on clinical questions (where they arose, clinical or managerial types of questions, etc.) provided useful data for developing information services in the hospital authority that provides over 90% of secondary and tertiary health care in Hong Kong in terms of patient days. The findings led to the development of an electronic knowledge gateway accessible from all 42 public hospitals, 24 hours a day.

CONCLUSION

The study found that the EBM approach in expressing the clinical problem as a question was not universally adopted by all groups of clinicians in hospitals. The triangulation methods have gathered interrelated evidence to reject the hypothesis that building well-structured clinical questions would mean higher satisfaction with obtained information and higher success in problem solving.

Table 1 Continued

Acknowledgments

The author expresses her gratitude to Associate Professor Peter Clayton, University of Canberra, Australia, for his valuable advice on the research. Special thanks are due to Michelle Siu, Christina Chau, Christina Soo, Susanna Li, Donna Hui, and Lewis Choi for their assistance and ardent support. She is indebted to all the librarians and colleagues in the Hong Kong Hospital Authority for their participation in her doctoral research, a part of which is presented in this article.

REFERENCES

- Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, and Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingston, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Elstein AS, Shulman LS, and Sprakfa SA. Medical problem solving: an analysis of clinical reasoning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, and Hayward RSA. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions,. ACP J Club. 1995 Nov/Dec; 123:A12–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, and Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingston, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, and Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingston, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, and Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingston, 2000, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Covell DG, Uman GC, and Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985 Oct; 103(4):596–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osheroff JA, Forsythe DE, Buchanan BG, Bankowitz RA, Blumenfeld BH, and Miller RA. Physicians' information needs: analysis of questions posed during clinical teaching. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Apr 1; 114(7):576–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covell DG, Uman GC, and Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985 Oct; 103(4):596–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson JW, German PS, Weiss R, Skinner EA, and Bowes F. Health science information management and continuing education of physicians: a survey of US primary care practitioners and their opinion leaders. Ann Intern Med. 1989 Jan 15; 110(2):151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SH, Benson DA. The medical information needs of internists and pediatricians at an academic medical center. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1989 Oct; 77(4):372–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart CJ, Hepworth JB. The value to clinical decision making of information supplied by NHS Library and Information Services, British Library R&D Report, no. 6205. Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, UK: The British Library Board, British Library Research and Development Department, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Ash J, and Wykoff L. Can primary care physicians' questions be answered using the medical journal literature? Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994 Apr; 82(2):140–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrie AR, Ward AM. Questioning behaviour in general practice: a pragmatic study. BMJ. 1997 Dec; 315(7121):1512–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpka T, Ekstrom M, and Bjurulf P. Information needs and information seeking behaviour in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1989 Jun; 7(2):105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Ash J, and Wykoff L. Can primary care physicians' questions be answered using the medical journal literature? Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994 Apr; 82(2):140–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, Bergus GR, Levy BT, Chambliss ML, and Evans ER. Analysis of questions asked by family doctors regarding patient care. BMJ. 1999 Aug 7; 319(7206):358–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser TC. The information needs of practicing physicians in Northeastern New York State. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1978 Apr; 66(2):200–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinson ER, Mueller DA. Survey of health professionals' information habits and needs: conducted through personal interviews. JAMA. 1980 Jan; 243(2):140–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpka T, Ekstrom M, and Bjurulf P. Information needs and information seeking behaviour in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1989 Jun; 7(2):105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SH, Benson DA. The medical information needs of internists and pediatricians at an academic medical center. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1989 Oct; 77(4):372–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden VM, Kromer ME, and Tobia RC. Assessment of physicians' information needs in five Texas counties. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994 Apr; 82(2):189–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covell DG, Uman GC, and Manning PR. Information needs in office practice: are they being met? Ann Intern Med. 1985 Oct; 103(4):596–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman PN, Ash J, and Wykoff L. Can primary care physicians' questions be answered using the medical journal literature? Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1994 Apr; 82(2):140–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart CJ, Hepworth JB. The value to clinical decision making of information supplied by NHS Library and Information Services, British Library R&D Report, no. 6205. Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, UK: The British Library Board, British Library Research and Development Department, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barrie AR, Ward AM. Questioning behaviour in general practice: a pragmatic study. BMJ. 1997 Dec; 315(7121):1512–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad-Garcia MF, Gonzalez-Teruel A, and Sanjuan-Nebot L. Information needs of physicians at the University Clinic Hospital in Valencia–Spain. In: Information Seeking in Context (ISIC): An International Conference on Information Needs, Seeking and Use in Different Contexts. Sheffield, UK: ISIC, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Osheroff JA, Forsythe DE, Buchanan BG, Bankowitz RA, Blumenfeld BH, and Miller RA. Physicians' information needs: analysis of questions posed during clinical teaching. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Apr 1; 114(7):576–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely J, Burch R, and Vinson D. The information needs of family physicians: case-specific clinical questions. J Fam Pract. 1992 Sep; 35(3):265–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ely JW, Osheroff JA, Ebell MH, Bergus GR, Levy BT, Chambliss ML, and Evans ER. Analysis of questions asked by family doctors regarding patient care. BMJ. 1999 Aug 7; 319(7206):358–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osheroff JA, Forsythe DE, Buchanan BG, Bankowitz RA, Blumenfeld BH, and Miller RA. Physicians' information needs: analysis of questions posed during clinical teaching. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Apr 1; 114(7):576–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson JW, German PS, Weiss R, Skinner EA, and Bowes F. Health science information management and continuing education of physicians: a survey of US primary care practitioners and their opinion leaders. Ann Intern Med. 1989 Jan 15; 110(2):151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. What clinical information do doctors need? BMJ. 1996 Oct; 313(7064):1062–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad-Garcia MF, Gonzalez-Teruel A, and Sanjuan-Nebot L. Information needs of physicians at the University Clinic Hospital in Valencia–Spain. In: Information Seeking in Context (ISIC): An International Conference on Information Needs, Seeking and Use in Different Contexts. Sheffield, UK: ISIC, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng GYT. Measuring electronic information services: the use of the Information Behavior Model [doctoral dissertation]. Canberra, Australia: University of Canberra, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moser CA, Kalton G. Survey methods in social investigation. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1972:85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1966:25. [Google Scholar]

- Sproull NL. Handbook of research methods: a guide for practitioners and students in the social sciences. 2nd ed. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow, 1995:139. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng GYT. Educational workshop improved information-seeking skills, knowledge, attitudes and the search outcome of hospital clinicians: a randomized controlled trial. Health Info Libr J. 2003 Jun; 20(Suppl 1):22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, and Haynes RB. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingston, 2000, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, and Hayward RSA. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions,. ACP J Club. 1995 Nov/Dec; 123:A12–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng GYT. Educational workshop improved information-seeking skills, knowledge, attitudes and the search outcome of hospital clinicians: a randomized controlled trial. Health Info Libr J. 2003 Jun; 20(Suppl 1):22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng GYT. Educational workshop improved information-seeking skills, knowledge, attitudes and the search outcome of hospital clinicians: a randomized controlled trial. Health Info Libr J. 2003 Jun; 20(Suppl 1):22–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]