Abstract

Introduction:

Although indoor tanning causes cancer, it remains relatively common among adolescents. Little is known about indoor tanning prevalence and habits in Canada, and even less about associated behaviours. This study explores the prevalence of adolescent indoor tanning in Manitoba and its association with other demographic characteristics and health behaviours.

Methods:

We conducted secondary analyses of the 2012/13 Manitoba Youth Health Survey data collected from Grade 7 to 12 students (n = 64 174) and examined associations between indoor tanning (whether participants had ever used artificial tanning equipment) and 25 variables. Variables with statistically significant associations to indoor tanning were tested for collinearity and grouped based on strong associations. For each group of highly associated variables, the variable with the greatest effect upon indoor tanning was placed into the final logistic regression model. Separate analyses were conducted for males and females to better understand sex-based differences, and analyses were adjusted for age.

Results:

Overall, 4% of male and 9% of female students reported indoor tanning, and prevalence increased with age. Relationships between indoor tanning and other variables were similar for male and female students. Binary logistic regression models indicated that several variables significantly predicted indoor tanning, including having part-time work, being physically active, engaging in various risk behaviours such as driving after drinking for males and unplanned sex after alcohol/drugs for females, experiencing someone say something bad about one’s body shape/size/appearance, identifying as trans or with another gender, consuming creatine/other supplements and, for females only, never/rarely using sun protection.

Conclusion:

Indoor tanning among adolescents was associated with age, part-time work, physical activity and many consumption behaviours and lifestyle risk factors. Though legislation prohibiting adolescent indoor tanning is critical, health promotion to discourage indoor tanning may be most beneficial if it also addresses these associated factors.

Keywords: indoor tanning, UV exposure, risk factors, skin cancer, youth, adolescents, students, Canada

Highlights

This study explores the prevalence of adolescent indoor tanning in Manitoba and its association with various demographic characteristics and health behaviours, for male and female students separately.

A greater proportion of older and female students have used indoor tanning equipment.

Most variables demonstrated significant associations through binary logistic regression.

Several variables significantly predict indoor tanning: part-time work, being physically active, risk behaviours such as drinking and driving (males) and unplanned sex after using alcohol/drugs (females), body-related bullying, gender identity, consuming creatine or other supplements and never/rarely using sun protection (females).

Though legislation prohibiting adolescent indoor tanning is critical, health promotion to discourage indoor tanning may be most beneficial if it also addresses these associated factors.

Introduction

Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer in Canada.1 In 2015, an estimated 6800 Canadians were diagnosed with melanoma, which accounts for about 80% of skin cancer deaths.2-3 While mortality is rare, the treatment-related costs of this disease are substantial and are projected to increase from about $466 million in 2004 to $922 million in 2031.3-4

Many skin cancers and the associated treatment costs are avoidable as up to 90% of skin cancers are due to ultraviolet (UV) exposure.5

Indoor tanning involves exposure to a concentrated source of UV light. On average, the radiation from indoor tanning equipment corresponds to a UV index of 13, which is considerably higher than the UV index of 8.5 associated with the noon summer sun at intermediate latitudes.6 Tanning beds’ UV emissions vary depending upon the design and power of the equipment, operator knowledge and compliance with federal guidelines.7 Furthermore, because the UV radiation emitted by indoor tanning equipment can vary across the effective area, and radiation in some areas can be 30% greater than the average, overexposure inevitably occurs.6 “Ever use” of tanning beds before the age of 25 was found to significantly increase melanoma risk,8-9 and correlations have also been found between indoor tanning and basal and squamous cell carcinoma.9-11

The National Sun Survey II1 (NSS2) estimated that 10.5% of the Canadians surveyed in 2006 tanned indoors in the past year, an increase from 7.7% in 1996, which suggests a growth in popularity. The NSS2 also found that indoor tanning is more common among females, particularly young women, a finding echoed by research conducted elsewhere.12-22 Fewer studies, however, have explored the sex differences in behaviours to do with indoor tanning.16-18,21,24 Robust cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys about indoor tanning behaviours are rare, no less so than in Canada.

Research and public health promotion efforts should target adolescents as they are at a critical age to prevent risk behaviours from developing. In fact, adolescents are less likely to try indoor tanning if they have not done so by a certain age.20 Exploring sex-based differences in behaviours to do with indoor tanning can help focus preventative strategies.24 Furthermore, the impacts of gender identity and sexual orientation on indoor tanning have not been investigated.

Poor self-image and low self-esteem are associated with indoor tanning among adolescents.12,22,25 Among male adolescents in the United States, a correlation between indoor tanning and a perception of being very overweight or very underweight and being a victim of bullying suggests that bullying and peer relationships also play a role.25

Indoor tanning is also correlated with smoking and susceptibility to smoking, binge drinking and drug use.12,13,16,18,20-22,24,26 It may be that adolescents who tan indoors are more susceptible to engage in risk behaviours despite the risks being well documented. The association between indoor tanning and risk behaviours that are unrelated to appearance enhancement suggests that some engage in these behaviours for other purposes, such as to cope with anxiety. For instance, a significant proportion of indoor tanners report that tanning lifts their spirits and is relaxing.20

While the literature examining the relationship between indoor tanning and the use of sunscreen outdoors is inconsistent,14,15,17,18 the relationship between indoor tanning and physical activity is also unclear. Several studies have found that adolescents who play on a sports team are more likely to tan indoors.18,27 Conversely, Demko et al.16 found that physical activity among female adolescents is associated with a lower likelihood of indoor tanning. Controlling for size of peer group and sun exposure through outdoor physical activity may shed some light on these conflicting findings.

Adolescents’ proximity to indoor tanning facilities also impacts their use. In the United States, shorter distances to indoor tanning facilities were correlated with greater use.23

The purpose of this secondary analysis of the 2012/13 Manitoba Youth Health Survey (YHS) is to

determine the prevalence of indoor tanning among Manitoba adolescents,

explore relationships between indoor tanning and an extensive set of variables to confirm or challenge findings in a Canadian setting and

generate new hypotheses around reasons for indoor tanning.

We hypothesize that indoor tanning will be positively associated with various risk behaviours (such as substance use), consumption behaviours related to bolstering appearance (i.e. indicative of weight control efforts), poorer mental well-being and being bullied.

Applying a social ecological model28 to this research helps us examine associated behaviours and risk factors and consider individual characteristics, social influences, communities, institutions, structures, policies and systems. In terms of institutional factors, legislation on indoor tanning came into force in June 2012 in Manitoba (before the Youth Health Survey was conducted). The legislation that was in effect at the time of this study required youth younger than 18 years to have written permission to tan indoors and those under 16 years to be accompanied by their parent or guardian. As this research is limited to individuals’ survey responses about varied health behaviours, and as all participants are residents of Manitoba (and are exposed to similar institutions, structures, policies and systems), we focus upon individual characteristics and social influence, where possible.

Methods

The Youth Health Survey and sampling procedures

The Manitoba YHS, a self-reported paper survey completed in school that includes questions about physical activity, eating behaviours, sun safety, mental well-being, bullying, school connectedness, tobacco use, drug and alcohol use, healthy sexuality and injury prevention, was designed and implemented by Partners in Planning for Healthy Living, a network of health and research partners from across Manitoba.29

All Manitoba schools, including independent, Francophone, Hutterite and First Nations schools, were invited to participate in the survey in the 2012/13 school year. Overall, 476 schools (73% of all eligible schools) conducted the 2012/13 survey, and 64 174 Grade 7 to 12 students (67% of all the students enrolled in the eligible grades in Manitoba) completed it.

Measures

The dependent variable used in this secondary analysis study is history of indoor tanning. Indoor tanning use was measured using responses to the question “Have you ever used any artificial tanning equipment such as a tanning bed, sunlamp or tanning light?” (possible responses were “Yes” or “No”). Only students with a valid answer to this question and who reported their sex (“male” or “female”) were included in analyses (n = 60 648; 95% of the entire Manitoba dataset). Each independent variable was analyzed independently, and missing answers were removed from each analysis if the student did not have a valid answer for the dependent and independent variables; as a result, the denominator is different for each independent variable.

For the urban/rural variable, schools were categorized as urban (schools in Winnipeg and Brandon) or rural (all other schools).

The descriptive characteristics and binary logistic regression included 25 independent variables (most with collapsed response categories for simplicity). These independent variables were selected based on previous research; some, such as smoking, were found to be significant in other research, whereas others, such as consumption behaviours and self-esteem, were related to a cluster of variables examined in other research. Descriptions of the independent variables and how they were derived are available on request from the authors.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed male and female students separately as a number of studies have found sex differences in the prevalence of indoor tanning, but few have explored whether the behaviours associated with indoor tanning differ.

We calculated the prevalence of indoor tanning and the frequencies of all variables. All variables were included in binary logistic regression models to determine the direction, significance and size of effect of all associations with indoor tanning. The binary logistic regression models also enabled investigating unique associations between similar variables and indoor tanning (e.g. if perceiving oneself as overweight was associated with indoor tanning whereas experiencing someone say something bad about one’s body shape/size/appearance was not). Binary logistic regression models were adjusted for age to observe the impacts of health behaviours independently of their relationship with age. Since the independent and dependent variables are categorical measures, we used chi-square analysis to examine the associated behaviours of students who have tanned indoors and those who have not, with an alpha level set at 0.05. Confidence intervals (CI) were set to 95%.

The binary logistic regression models explored the relationship between independent variables and indoor tanning, and demonstrated significant positive or negative associations for most variables. In other words, there were too many significant variables to include in the final logistic regression models. To reduce the number of variables for the final logistic regression models, we tested for collinearity between significant variables for each sex. This involved analyzing two-by-two tables of all combinations of independent variables and examining relationships between the two independent variables. Independent variables that had skewed distributions were indicative of correlations. Testing for collinearity revealed several groups of highly correlated variables that differed slightly for male and female adolescents. We used the variable with the greatest effect in the final logistic regression model as a proxy for the group of highly correlated variables. Significant variables from the initial binary logistic regression that were not highly correlated to any other variables were also placed in the final logistic regression models. The final logistic regression model explored the significance of variables’ relationship to indoor tanning once all variables were included in the model.

We used forward selection to determine the significance of independent variables within the final logistic regression models. These models were adjusted for age. Analyses were completed using statistical package SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) in the Department of Epidemiology and Cancer Registry at CancerCare Manitoba.

Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba.

Results

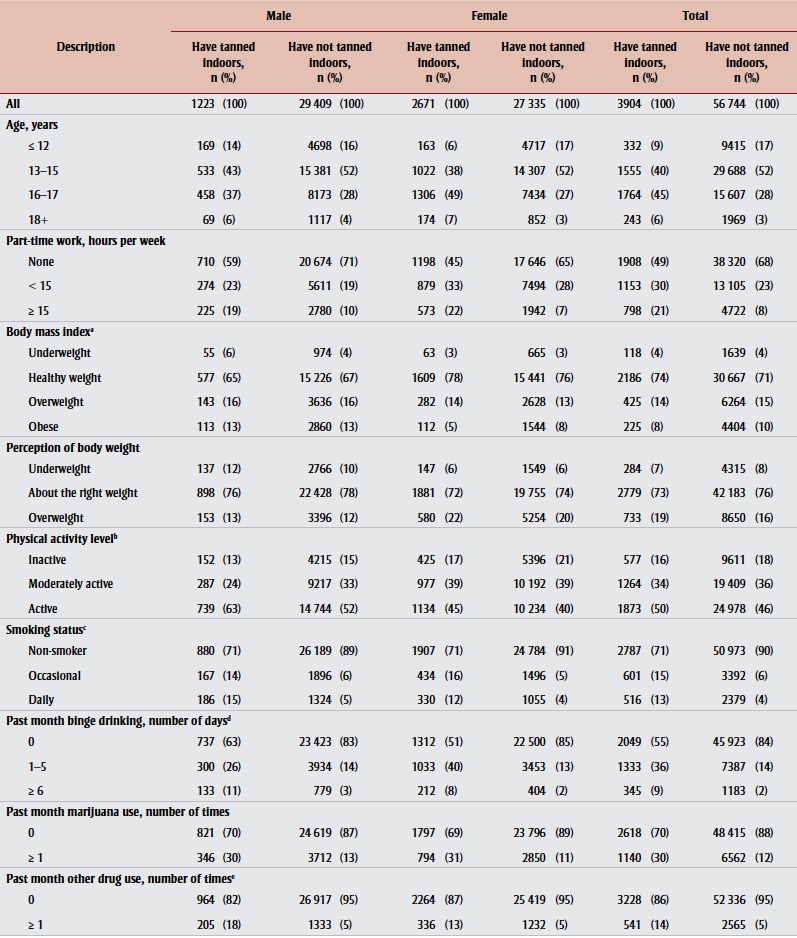

Overall, 4% (1223/30 642) of male and 9% (2671/30 006) of female students had used indoor tanning equipment in their lifetime. Table 1 shows that students who use indoor tanning equipment, and particularly girls, tend to be older than those who do not (56% of girls who tanned indoors were 15 years and older compared to 30% of girls who had not tanned indoors).

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of Grades 7 to 12 students by indoor tanning status and by sex, Manitoba, 2012.

|

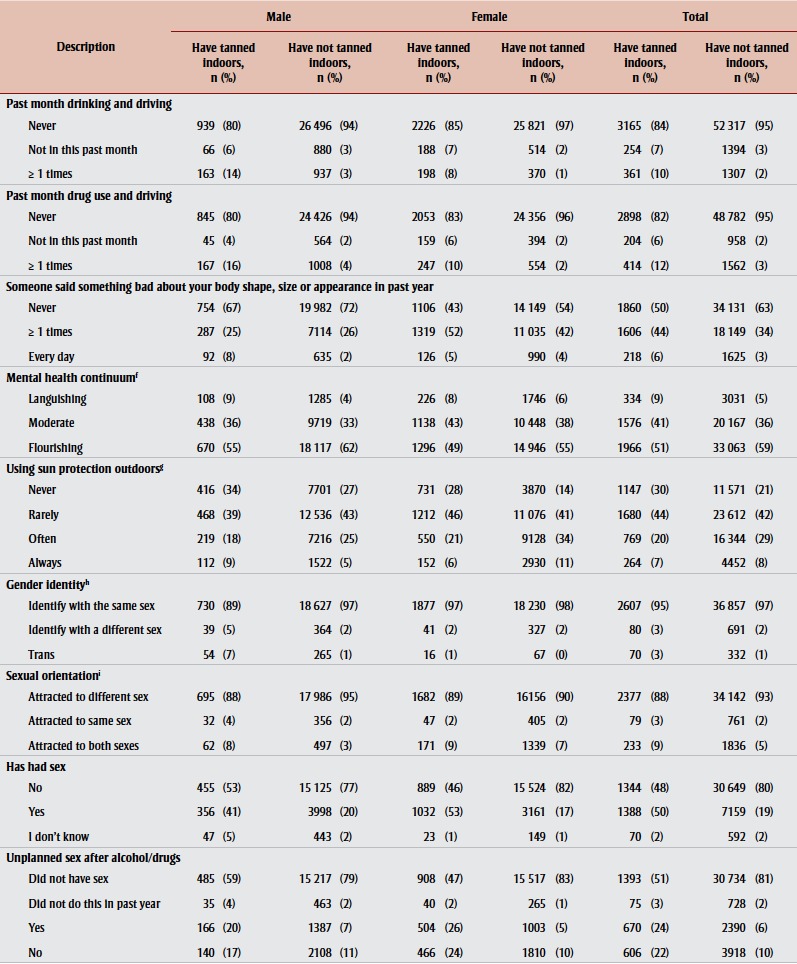

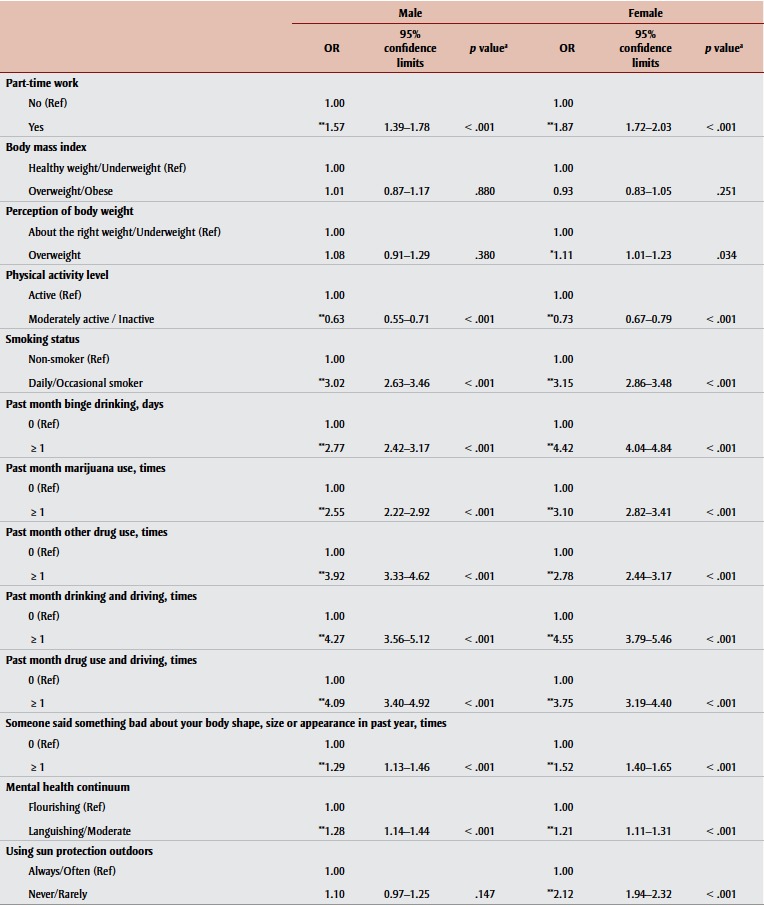

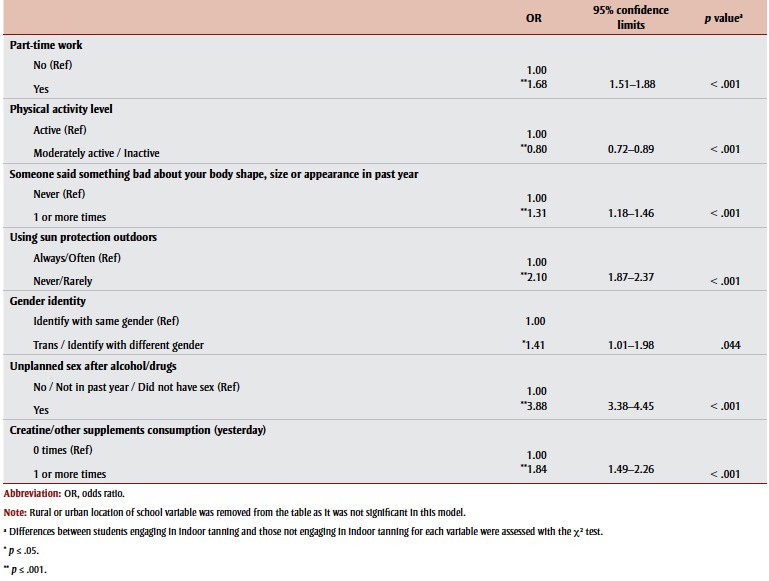

The unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) of having used indoor tanning equipment are shown in Table 2. We examined separate datasets for male and female students and adjusted the results for age. Response categories were collapsed so that each independent variable had two categories.

Table 2. Indoor tanning among male and female Grade 7-12 students, by demographic characteristics and health behaviours, adjusted for age, Manitoba, 2012.

|

The binary logistic regression of students’ behaviours (Table 2) found that indoor tanning was significantly associated with having part-time work; being physically active; smoking; binge drinking; marijuana and other drug use; drinking or drug use and driving; experiencing someone say something bad about one’s body shape/size/appearance; having poorer mental well-being; identifying as trans or with a different gender; having had sex; having unplanned sex after alcohol/drugs; drinking soft drinks and diet soft drinks; taking creatine/other supplements; consuming meal replacement bars or shakes; and eating fast food.

In addition, female students’ indoor tanning was also associated with perceiving oneself as overweight, never/ rarely using sun protection and attending a rural school, while male students’ indoor tanning was also associated with being attracted to the same sex or both sexes and eating vegetables/fruit four or more times in a day.

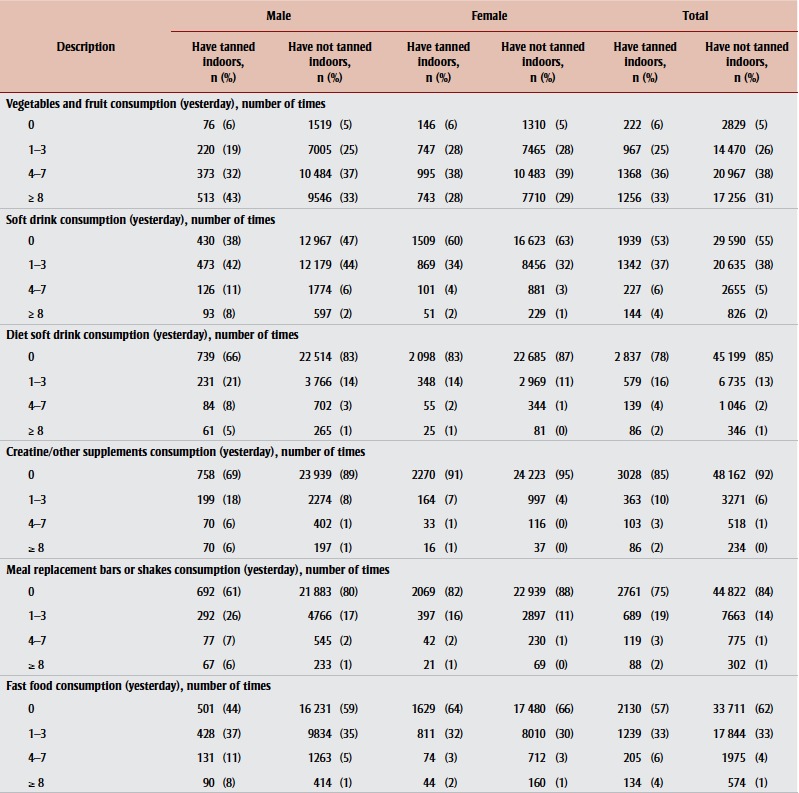

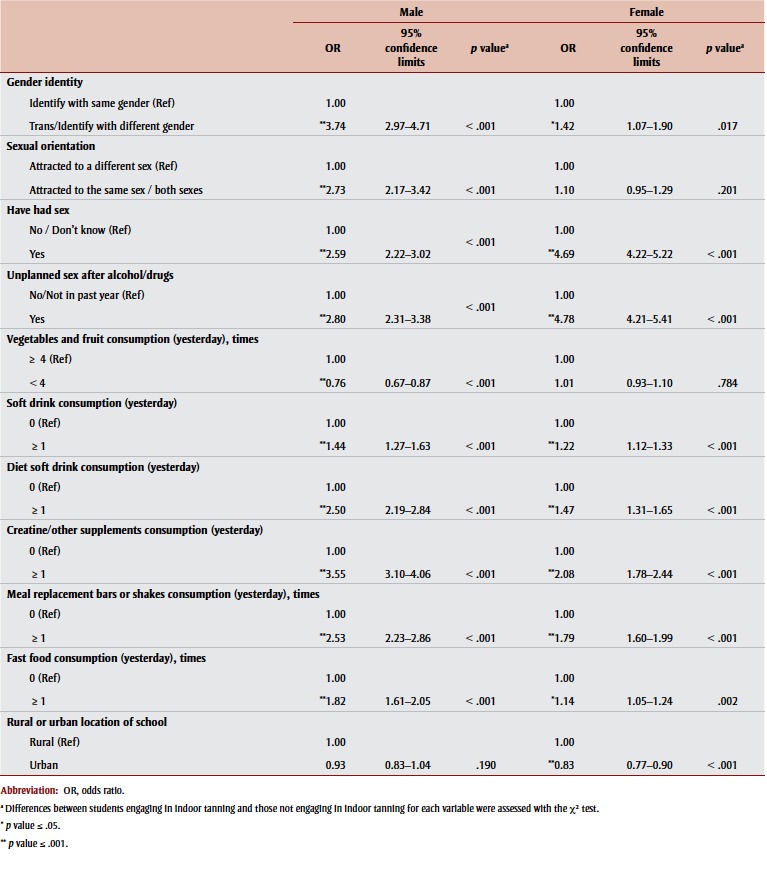

We found a strong correlation between several groupings of variables among male students: physical activity level and fruit and vegetable consumption (of these, physical activity had the greater effect related to indoor tanning); smoking, binge drinking, marijuana use, other drug use, drinking and driving, drug use and driving, having had sex and having had unplanned sex after using alcohol/drugs (of these, drinking and driving had the greatest effect related to indoor tanning); experiencing someone say something bad about one’s body shape/size/appearance and having poorer mental well-being (of these, the former had the greater effect related to indoor tanning); identifying as trans or with a different gender and being attracted to the same sex or both sexes (of these, identifying as trans or with a different gender had the greater effect related to indoor tanning); and consuming soft drinks, diet soft drinks, creatine/other supplements, meal replacement bars/ shakes and fast food (of these, creatine/ other supplements consumption had the greatest effect related to indoor tanning). For male students, having part-time work was not strongly associated with any other variables, but we nevertheless added it to the final logistic regression model.

The results for the final logistic regression model for male students are shown in Table 3. Having part-time work; being physically active; drinking and driving; experiencing someone say something bad about one’s body shape/size/appearance; identifying as trans or with a different gender; and consuming creatine/other supplements all maintained their significant associations with indoor tanning.

Table 3. Indoor tanning behaviours among male Grade 7-12 students by demographic characteristics and health behaviours, adjusted for age, Manitoba, 2012.

|

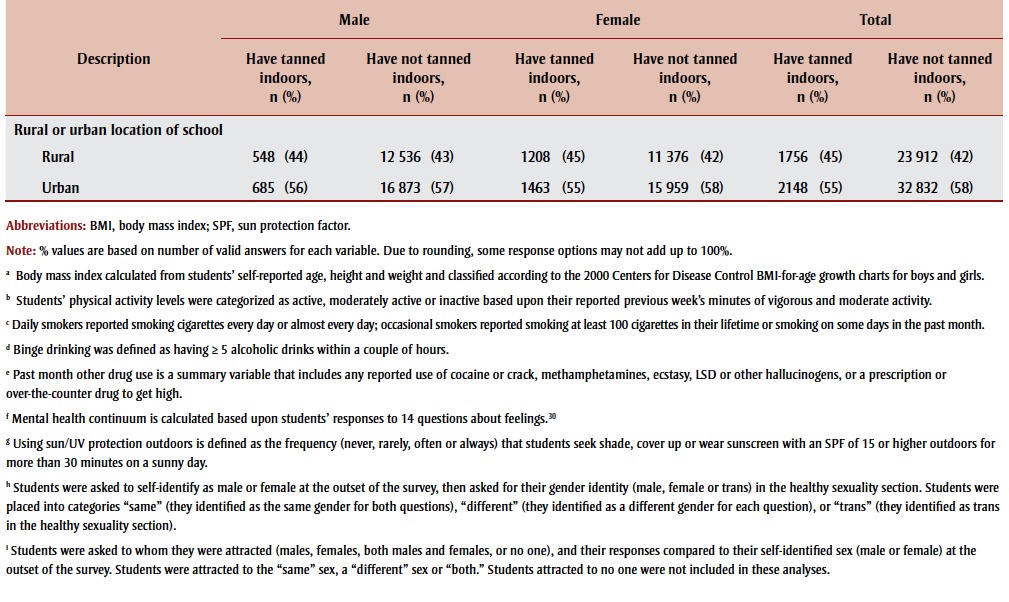

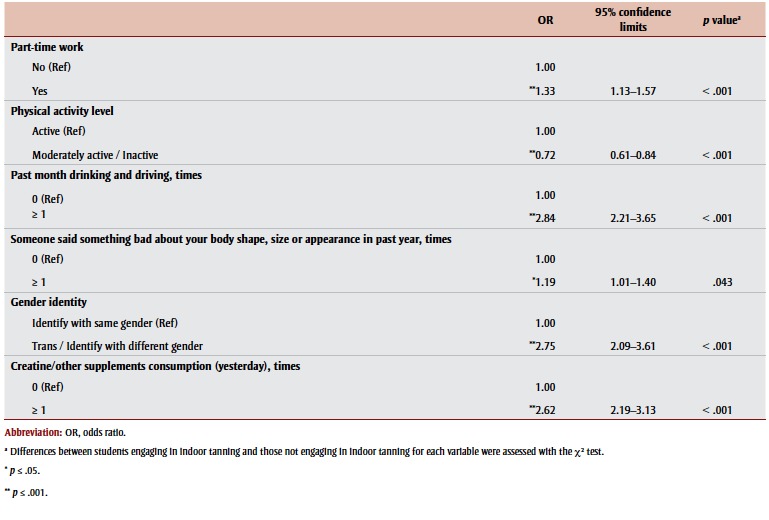

When testing for collinearity among significant variables of female students, we found a strong correlation between several groupings of variables: smoking, binge drinking, marijuana use, other drug use, drinking and driving, drug use and driving, having had sex, and having had unplanned sex after alcohol/drugs (of these, unplanned sex after alcohol/ drugs had the greatest effect related to indoor tanning); experiencing someone say something bad about one’s body shape/size/appearance, perceiving oneself as overweight and having poorer mental well-being (of these, experiencing someone say something bad about one’s body shape/size/appearance had the greater effect related to indoor tanning); and consuming soft drinks, diet soft drinks, creatine/other supplements, meal replacement bars/shakes and fast food (of these, creatine/other supplements consumption had the greatest effect related to indoor tanning). For female students, having part-time work, being physically active, using sun protection, gender identity and rural location of school were not strongly associated with any other variables. These were added to the final logistic regression model as well.

The results for the final logistic regression model for female students are shown in Table 4. Having part-time work, being physically active, experiencing someone say something bad about one’s body shape/size/appearance, never/rarely using sun protection, identifying as trans or with a different gender, having had unplanned sex after alcohol/drugs and consuming creatine/other supplements all maintained their significant associations with indoor tanning. Going to a rural school lost its significant association with indoor tanning in the final logistic regression model.

Table 4. Indoor tanning behaviours among female Grade 7-12 students by demographic characteristics and health behaviours, adjusted for age, Manitoba, 2012.

|

Discussion

Our research expands upon worldwide examinations of indoor tanning and associated behaviours among adolescents. This is also the first large-scale study of indoor tanning and associated behaviours exclusively among Canadian adolescents.

Our results suggest that several groupings of factors are associated with adolescents’ indoor tanning. A combination of individual characteristics, social influences and community factors are likely at the root of these relationships. Many associations were similar for male and female students.

For both male and female students, part-time work played a significant role in indoor tanning behaviour. This association with part-time work may indicate that people who use indoor tanning equipment are more likely to have spending money than non-users. This is consistent with a study by Mayer et al.23 that found that having a larger allowance was predictive of indoor tanning. It is possible that some associated behaviours are partly explained by adolescents’ spending patterns.

The association between indoor tanning and fast food and soft drink consumption was unexpected as most other consumption behaviours associated with indoor tanning relate more closely to appearance and weight control (creatine/other supplements and meal replacement bars).

Positive attitudes towards indoor tanning and a tanned appearance more often lead to adolescents’ indoor tanning.14,20,26 For female students, indoor tanning was associated with perceiving oneself as overweight and someone saying something bad about their body shape, size or appearance, but not with body mass index itself. This suggests that indoor tanning is used as a tool to improve one’s appearance and is linked to greater self-consciousness about one’s body. Alternately, as other studies suggest, being bullied may be related to indoor tanning independently of body image.20,26

For both male and female students, experiencing someone say something bad about their body shape, size or appearance had a stronger association (greater significance and size of effect) with indoor tanning than their perceiving themselves overweight. This suggests that indoor tanning may function as a coping mechanism, at least in part. This is confirmed by the associations between indoor tanning and poorer mental well-being, suggesting that indoor tanning is the product of the interaction between body-related insecurity and efforts to cope.

Furthermore, the consistent association between indoor tanning and behaviours not related to appearance—smoking, binge drinking, marijuana use, other drug use, drinking and driving, drug use and driving, having had sex and having had unplanned sex after alcohol/drugs—may indicate that indoor tanning is one of a number of risk behaviours used for coping. This association may also indicate that these individuals do not prioritize health behaviours despite knowing their benefits. Mayer et al.23 found that adolescents who tan indoors have greater knowledge of the risks surrounding indoor tanning, likely due to greater exposure to health warnings while at indoor tanning facilities. Further education on the dangers of UV exposure and benefits of protective behaviours alone is therefore unlikely to reduce their use of indoor tanning; interventions targeting attitudes in relation to appearance have been found to be more effective.30 Other cultural factors that could be determined through a focus group or in interview setting may be at play. Open-ended questions about the reasons for and attitudes towards indoor tanning could better address this gap in the research.

We should also consider the implications of social influence upon indoor tanning. Adolescents who tan indoors may be more likely to justify risk behaviours due to the risk behaviours of their peer group. The attitudes and behaviours of peers and parents, and adolescents’ perception of these, have been found to significantly impact adolescents’ indoor tanning.17,19,20,22

As many adolescents are accompanied by their parents when they initiate indoor tanning, legislation requiring that adolescents have signed parental consent (legislation in effect at the time of the survey) may do little to curb this behaviour. An indoor tanning ban for people younger than 18 years came into effect in Manitoba on January 1, 2016. This then limits indoor tanning to youth with a prescription from a health professional, youth with access to home indoor tanning equipment and youth who use indoor tanning facilities that do not adhere to legislation.

While social influence may be at root of the relationships between indoor tanning and various risk behaviours, the association between indoor tanning and physical activity (a healthy behaviour) for both male and female students may also be attributed to social influence. Guy et al.18 and Miyamoto et al.27 found that sports team membership is associated with indoor tanning. Unfortunately these studies did not control for size and variety of peer group (which may bolster an adolescent’s exposure to more diverse attitudes and behaviours) or unprotected outdoor UV exposure (which may contribute to skin darkening). However, these analyses also find that female students who never or rarely use sun protection are almost twice as likely to tan indoors, suggesting a relationship between purposefully seeking UV exposure via indoor tanning and neglecting to protect against outdoor UV exposure.

Another sex-based difference was the relationships between indoor tanning and gender identity for male students, and between indoor tanning and sexual activity for female students. While all of these associations were significant for both male and female students, the size of the effect varied between the sexes. The final logistic regression model found that male students who identify as trans or with a different gender are nearly three times as likely to have used indoor tanning equipment, compared to 1.41 times as likely for female students. Similarly, binary logistic regression found that sexual orientation is significantly associated with indoor tanning for male students, but not for female students. The association between indoor tanning and identifying as trans or with a different gender among male students may be indicative of a lesser adherence to traditionally perceived gender norms. Alternately, the size of effect of sexual activities (having had sex, having had unplanned sex after alcohol/drugs) upon indoor tanning for female students was greater than that for male. There may be a greater sense of body consciousness and concern about appearance among sexually active female adolescents. A more in-depth investigation into adolescents’ attitudes and reasons for indoor tanning could investigate these relationships.

Finally, the association between indoor tanning and a student’s school being in a rural area was significant only for female students. This may suggest that the culture of risk behaviours or appearance enhancement differs subtly between rural and urban settings for female adolescents only. However, this association lost significance in the final logistic regression model when adjusting for other variables.

Given the complex interaction of individual characteristics and social influences contributing to adolescents’ indoor tanning, identifying opportune areas for preventive strategies is challenging. However, a consistent theme through much of this study is that indoor tanning is indicative of body self-consciousness and/or efforts to enhance one’s appearance. This underlying reason may contribute to the association of indoor tanning with consumption of creatine or other supplements and meal replacement bars or shakes (particularly for male students); physical activity; sexual activity (particularly for female students); identifying as trans or with another gender (particularly for male students); experiencing someone say something bad about one’s body shape/ size/appearance; and even using sun protection (for female students). Interventions or campaigns that address healthy body image and highlight indoor tanning’s detrimental effects upon appearance, especially at this critical age, could have a significant impact.

The association between indoor tanning and a number of risk behaviours that are unrelated to appearance enhancement were more challenging to address. These risk behaviours may be indicative of poorer mental well-being, coping efforts, peer pressure or feelings of invincibility despite knowledge of the negative outcomes. Continued efforts targeting mental health and encouraging healthy behaviours may have positive effects regarding indoor tanning as well.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this research is that the extensive list of variables included in analyses allowed us to explore the associations between many behaviours and indoor tanning that have not been previously explored simultaneously. The test for collinearity enabled grouping of variables related to indoor tanning and each other, and highlighted variables that are not associated with each other but are independently associated with indoor tanning. The final logistic regression model allowed for the examination of the strength of the association between variables (or groups of variables) and indoor tanning when interacting.

A limitation of this study is that the YHS was not completed by 27% of eligible schools and 33% of Grade 7 to 12 Manitoba students. Most of the schools not represented were independent schools (not within a school division), Hutterite schools and First Nations schools. Many of these are within very small communities likely without access to indoor tanning equipment. However, many of these schools did participate. We examined the extent of similarity between schools by applying the logistic generalized estimating equation GEE model to the student data. The intra-class correlation within schools was very low (< 0.01 for male students and 0.03 for female students), suggesting that multilevel modelling was not necessary.

An additional limitation was that the YHS was not completed by adolescents who were not enrolled in school or in attendance when the questionnaire was implemented. It is likely that adolescents who were absent are more likely to be older and more likely to engage in risk behaviours. As older age and risk behaviours are associated with indoor tanning, the non-participation of these students would actually suppress indoor tanning prevalence. It is impossible to know the exact effect of this limitation upon the results.

As the YHS relies on self-reporting, the findings may be subject to recall bias and response bias.

Finally, the YHS’s time and space constraints led to the omission of questions that contribute to a greater understanding of who and why adolescents are tanning indoors, such as skin tone, attitudes or beliefs. Only one question determined the prevalence of indoor tanning (ever use of indoor tanning equipment) and there were no measures of the frequency of indoor tanning. Similarly, all questions about food and drink consumption were based on “yesterday’s” consumption, substance use was based on behaviours from the “past month (30 days)” and physical activity was based on the “past week.” These time spans are used as a proxy for regular habits. There is a risk that participants’ behaviours reported are not representative of their regular habits.

Conclusion

This research highlights the significance of appearance enhancement and risk behaviours, and suggests that both individual characteristics and social influence contribute to indoor tanning.

Since these indoor tanning data were collected, most provinces, including Manitoba, have put into force legislation prohibiting the sale of indoor tanning to adolescents younger than 18 years. This legislation should limit access during a critical time, reducing the likelihood of initiating indoor tanning later in life. However, this research can be applied to design interventions targeting adults who choose to use indoor tanning equipment.

With a greater knowledge of adolescents’ behaviours, policy makers, health practitioners, health promotion staff, parents and educators are better equipped to identify and discuss opportunities to improve adolescent and overall health. Although the landscape of indoor tanning is changing with current shifts in policy and awareness, continued work is needed to address positive attitudes towards a tanned appearance and the underlying reasons for adolescents’ risk behaviours.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by CancerCare Manitoba and CancerCare Manitoba Foundation. We owe thanks to Partners in Planning for Healthy Living, particularly Manitoba’s regional health authorities, for collecting the 2012/13 YHS; to the school divisions and schools across Manitoba for their participation; and to the students who responded to the survey with enthusiasm, honesty and willingness.

The authors have no financial disclosures to report.

References

- National Skin Cancer Prevention Committee. Canadian Partnership Against Cancer, Toronto (ON): 2010. Exposure to and protection from the sun in Canada: a report based on the 2006 Second National Sun Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Toronto (ON):: 2015 [cited 2015 Aug 14]. Canadian cancer statistics 2015. Special topic: predictions of the future burden of cancer in Canada [Internet]. . Available from: http://tinyurl.com/obd2tus. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger H, Williams D, Chomiak M, Trenaman L. Toronto (ON):: 2010 [cited 2015 Aug 14]. The economic burden of skin cancer in Canada: current and projected [Internet]. . Available from: http:// www.cancercare.ns.ca/site-cc/media/ cancercare/Economic%20Burden%20 of%2 0Skin%2 0Cancer%2 0in%2 0 Canada%20Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JA, Quantz SD, Ashbury ED, Sauvé JK. 101(4) 2010: The Skin Cancer Prevention Framework: a comprehensive tool for population-level efforts in skin cancer. Can J Public Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health consequences of excessive solar UV radiation [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2006 [cited 2016 May 27] . Available from: http://www.who.int/ mediacentre/news/notes/2006/np16/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Gerber B, Mathys P, Moser M, Bressoud D, Braun-Fahrlander C. Ultraviolet emission spectra of sunbeds. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;76((6)):664–8. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)076<0664:uesos>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HW, James WD, Rigel DS, Maloney ME, Spencer JM, Bhushan R. Adverse effects of ultraviolet radiation from the use of indoor tanning equipment: time to ban the tan. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.032. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. jaad.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio S, Bracken MB, Beecker J. The association of indoor tanning and melanoma in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70((5)):847–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.050. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. jaad.2013.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on Artificial Ultraviolet (UV) Light and Skin Cancer. The association of use of sunbeds with cutaneous malignant melanoma and other skin cancers: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2007;120((5)):1116–22. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehner MR, Shive ML, Chren MM, Han J, Qureshi AA, Linos E. Indoor tanning and non-melanoma skin cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5909. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Qureshi AA, Geller AC, Frazier L, Hunter DJ, Han J. Use of tanning beds and incidence of skin cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30((14)):1588–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.3652. http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/ JCO.2011.39.3652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldeman C, Jansson B, Nilsson B, Ullén H. Sunbed use in Swedish urban adolescents related to behavioural characteristics. Prev Med. 1997;26((1)):114–9. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.9986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldeman C, Jansson B, Dal H, Ullén H. Sunbed use in Swedish adolescents in the 1990s: a decline with an unchanged relationship to health risk behaviours. Scand J Public Health. 2003;31((3)):233–7. doi: 10.1080/14034940310001208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides V, Weinstock M, Lazovich D, Ward E, Thun M. Indoor tanning use among adolescents in the U.S., 1998 to 2004. Cancer. 2009;115((1)):190–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokkinides VE, Bandi P, Weinstock MA, Ward E. Use of sunless tanning products among U.S. adolescents aged 11 to 18 years. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146((9)):987–92. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archdermatol.2010.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demko CA, Borawski EA, Debanne SM, Cooper KD, Stange KC. Use of indoor tanning facilities by white adolescents in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolescent Med. 2003;157((9)):854–60. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.9.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller AC, Colditz G, Oliveria S, et al. Use of sunscreen, sunburning rates, and tanning bed use among more than 10 000 US children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2002;109((6)):1009–14. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy GP, Jr, Berkowitz Z, Tai E, Holman DM, Everett Jones S, Richardson LC. Indoor tanning among high school students in the United States, 2009 and 2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150((5)):501–11. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerster KD, Mayer JA, Woodruff SI, Malcarne V, Roesch SC, Clapp E. The influence of parents and peers on adolescent indoor tanning behaviour: findings from a multi-city sample. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57((6)):990–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazovich D, Forster J, Sorensen G, et al. Characteristics associated with use or intention to use indoor tanning among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158((9)):918–24. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay H, Lowe D, Edwards D, Rogers SN. A survey of 14 to 16 year olds as to their attitude toward and use of sunbeds. Health Educ J. 2007;66((2)):141–52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0017896907076753. [Google Scholar]

- O’Riordan DL, Field AE, Geller AC, et al. Frequent tanning bed use, weight concerns, and other health risk behaviours in adolescent females (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17((5)):679–86. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer JA, Woodruff SI, Slymen DJ, Sallis JF, Forster JL, Clapp EJ et al. Adolescents’ use of indoor tanning: a large-scale evaluation of psychosocial, environmental, and policy-level correlates. Am J Public Health. 2011;101((5)):930–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300079. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher CE, Danoff-Burg S. Indoor tanning, mental health and substance use among college students: the significance of gender. J Health Psychol. 2010;15((6)):819–27. doi: 10.1177/1359105309357091. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359105309357091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blashill AJ, Traeger L. Indoor tanning use among adolescent males: the role of perceived weight and bullying. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46((2)):232–6. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9491-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s12160-013-9491-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagdasarov Z, Banerjee S, Greene K, Campo S. Indoor tanning and problem behaviour. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56((5)):555–62. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.555-562. http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/ JACH.56.5.555-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto J, Berkowitz Z, Jones SE, Saraiya M. Indoor tanning device use among male high school students in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50((3)):308–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D. Establishing and maintaining healthy environments. Toward a social ecology of health promotion. Am Psychol. 1992;47((1)):6–22. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partners in Planning for Healthy Living. Winnipeg (MB):: 2014 [cited 2014 Dec 15]. Manitoba Youth Health Survey [Internet]. . Available from: http://partners.healthincommon.ca/tools-and-resources/youth-health-survey/ [Google Scholar]

- Hillhouse JJ, Turrisi R, Kastner M. Modeling tanning salon behavioral tendencies using appearance motivation, self-monitoring and the theory of planned behaviour. Health Educ Res. 2000;15((4)):405–14. doi: 10.1093/her/15.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brief description of the mental health continuum short form (MHC-SF) [Internet]. Keyes CL. Atlanta (GA): 2009. [cited 2015 Aug 4] . Available from: https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/MHC-SFEnglish.pdf. [Google Scholar]