BACKGROUND

Overall error avoidance and analysis of errors, with the intent of learning from mistakes and preventing future occurrences, are critical issues for persons involved in all aspects of health care. Launched in 1999 by the release of the Institute of Medicine's report “To Err Is Human” [1], a dialogue in health care has been continually nurtured by the reports of that organization [2–4]; new organizations devoted to patient safety, such as the National Patient Safety Foundation† and the National Quality Forum‡; and state initiatives seeking ways to improve the situation, such as the Massachusetts Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors§ or Virginians Improving Patient Care and Safety (VIPCS).**

Surveys have been used by the patient safety community to not only glean information from the patient community about their awareness of patient safety issues [5], but to gauge individuals' comfort with the culture of safety at their health care organization [6] and to assess the quality of processes in place to assure safe medication delivery [7]. Yet none of these surveys, to the authors' knowledge, have reached out specifically to the community of library and information professionals to seek knowledge about their involvement in safety efforts. The medical library community collects benchmark data from its members on various resources, populations served, and traffic data but does not specifically include queries about medical librarians' contributions to safety from a distinct systems or safety perspective [8].

To begin filling this gap, an exploratory survey was undertaken to assess whether or not information professionals were directly involved in patient safety initiatives and how much they believed they could positively affect patient safety in the organizations in which they worked. One anticipated outcome of the survey was documentation of whether or not information professionals saw themselves as substantively contributing to safety initiatives by aligning themselves with this leadership-valued issue. Questions were developed by two information professionals with backgrounds in (a) patient safety and medical information and (b) strategic planning for information centers, including analysis of return on investment (ROI) and content selection and evaluation. Prior to posting, the questions were reviewed by five information professionals representing a variety of clinical environments.

It should be noted that the terms “librarians” and “information professionals” are used interchangeably in this paper as a number of persons working in information and knowledge management in health care environments have transitioned to such roles from information technology, clinical work, or other areas and are not specifically trained as librarians.

METHODOLOGY

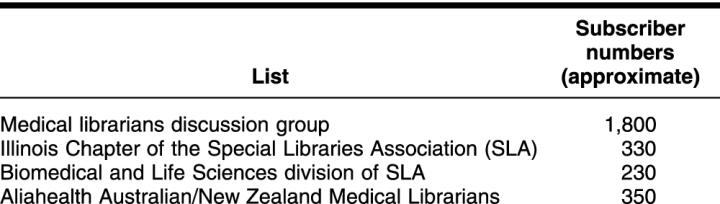

The survey was announced in May 2003 on discussion lists for information professionals in the health care, medical, and pharmaceutical sectors. Table 1 presents the queried lists. The total number of subscribers on these lists was approximately 2,700, and some interested parties forwarded announcements of the survey to colleagues on other discussion lists and in other countries; the extent of the circulation is not definitely known.

Table 1 Queried email discussion lists

The sampling of 142 responses collected from health care information professionals provides early and limited insights into the extent to which patient safety initiatives are an explicit concern for them. The low response rate is an indicator in itself. Individuals typically respond to a survey when they are interested in the topical area and when they have something to contribute. Members of any community ignore requests to participate in a survey if they are not interested in the topic, are not involved with the area being studied, have nothing to contribute, are simply too busy, or are not interested in the incentive [9]. Based on some of the responses, there is a need for a much greater level of awareness about the topic and guidance in how information professionals can become involved with patient safety efforts.

KEY FINDINGS

The culture of safety has not permeated the library community in the sense of leaders and administrators seeing librarians as having a crucial role in improving safety.

Leadership in health care organizations is not proactive about recruiting librarians to take part in the safety work of their organizations.

Information professionals and librarians responding to the survey are aware of the importance of patient safety initiatives.

Some information professionals are proactively becoming involved with safety initiatives—particularly promoting the role of evidence-based medical decisions.

Information professionals have interesting opportunities to define their roles in and contributions to this vitally important area.

Of the survey participants, 47.4% worked in teaching hospitals, 21.4% in nonteaching hospitals, 11.6% in academic medical centers, 6.4% in health care–related organizations (such as pharmaceutical companies), and 5.8% in other health care environments (such as a not-for-profit organization). Thirteen persons (7.5%) selected “Other” and identified work places such as medical professional associations and law firms.

Current activities by librarians related to safety were explored. Only 4 of the 142 respondents believed they had no role in patient safety initiatives. Of the respondents, 83.1% responded to ad hoc inquiries on patient safety. A significant number—48% and 46%, respectively—created resource guides (e.g., Websites, brochures, and guides to articles or books) for patients and practitioners and provided training for practitioners who wished to increase their skills.

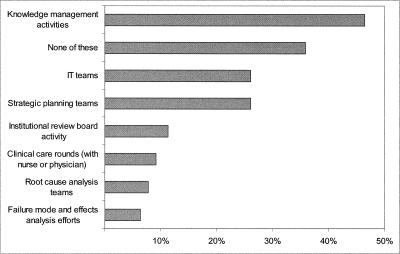

Only twenty persons (14% of persons responding) created and maintained knowledgebases of incidents and institutional responses. While they might still be sensitive about dealing with errors and incidents, information professionals could use their skills in organizing information, making it easy for the information to be analyzed and shared. This true knowledge-management effort has profound implications for organizational learning (Figure 1). The last five activities in Figure 1 are proactive roles for information professionals in minimizing error and promoting safety.

Figure 1.

Activities in which information professionals are included

Responses indicated that opportunities for information professionals to learn about safety were not robust. Of the survey participants, 58.5% indicated that the library staff did not participate in organization-sponsored events designed to increase understanding of patient safety practices or in meetings outside of the workplace on this topic. Sixty-four percent of survey participants indicated that their supervisor did not talk with them about their work in the context of safety.

However, the authors find that the library community seems to have made inroads into a major issue that is difficult for many departments—that of openly discussing errors. The impact of the errors considered by this set of respondents might be less than catastrophic, and hence broaching the subject is easier. However, the openness to learning from mistakes is a key attribute of a culture of safety [10]. It is encouraging that the library community has accepted this review-and-improvement process as a normal way of working.

A parallel point is that 67% of respondents indicate that weaknesses in library services and products are openly discussed with a goal of making improvements. In a microcosm, information centers have organized themselves to be learning organizations. Stringent and ongoing process review with a goal of continuous learning and improvement is a hallmark of the learning organization.

Six areas percolate to the top when reviewing the narrative answers to the question asking librarians about “what keeps them up at night?” regarding safety and the information transfer process at their institutions. Whereas the results might not be fully representative of the profession as a whole, the authors believe that the results can provide a snapshot of areas of concern for librarians and their roles in safety.

The six general areas of concern relate to:

Culture: inbred notions, norms, and philosophies of the organization that affect how work is done

Leadership: relationships between leaders and administrators in the librarian's organization and the library staff

Process: the ways certain tasks are accomplished and the defined ways of doing them

Research skills: the impact of real or perceived expertise by clinicians in online and Web-based research on the process of information identification and use

Individual responsibilities and skills: the individual professional's competencies and the ways they affect the professional's safety role

Resources/access issues and time factors: blunt end factors such as budget, technology, personnel, and collection items

DISCUSSION

Librarians and information professionals should have an integral role in patient safety efforts. Results of this exploratory study indicate a level of comfort with discussing errors with an eye toward improvement. An innovative and proactive relationship between librarians and those responsible for patient safety initiatives should be nurtured to most effectively identify, acquire, and disseminate information to support system improvements, learning organization behaviors, and clinical decisions, so that the information dimensions of patient safety are fully integrated and leveraged (Figure 2). Such a relationship will also encourage the creative thinking, feedback loops, and constructive dialogue needed to alter the status quo and mental models about the library profession that inhibit change. Value and ROI for such initiatives will ultimately be measured by a reduction in the number of days patients are hospitalized, fewer legal actions, and improved diagnostic and treatment strategies as a result of access to accurate and timely information.

Figure 2.

- Involvement with instituting a personal digital assistant (PDA) program to assist in answering questions at the point of care

- Updates to hospital policy and procedures to reflect current thinking

- Role on the clinical team for information professionals by proactively providing point-to-point dissemination of patient safety information

- Active clinical librarianship program that affects how clinicians find and utilize relevant evidence

- Literature search activity for patient safety initiatives, practice guidelines review, and root cause analysis

- Personal relationships with patient safety officers, risk management, and other quality personnel to establish an effective information exchange relationship

- Involvement in root cause analysis efforts

- Participation on the medication errors reduction team

- Effort to make library resources available to the clinical team, 24/7

Further study is required for a deeper understanding of the actual role of information professionals with respect to patient safety and perceptions regarding the interplay among information professionals, organization leadership, and patients. More probing about how librarians view the value of their experience and training in contributing to patient safety programs would be beneficial. For communicating best practices, it is important to learn about initiatives that are led by the library versus those which the library has been invited to participate in, and it is important to describe the culture of those organizations, documenting what the library has done that helped the parent institution perceive the library's value in a patient safety initiative. This activity would help to draw a clear connection between information work and patient safety improvements. It would also provide the industry with models to expand upon in recruiting the information sector and to assist in identifying metrics from which to measure the impact of these activities on the outcomes of safety initiatives.

Footnotes

* Presented as a poster session at the Fifth Annual Wisconsin Patient Safety Forum Meeting; Oconomowoc, Wisconsin; November 12–13, 2003.

† The National Patient Safety Foundation Website may be viewed at http://www.npsf.org.

‡ The National Quality Forum Website may be viewed at http://www.qualityforum.org.

§ The Massachusetts Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors may be viewed at http://www.macoalition.org.

** The Virginians Improving Patient Care and Safety (VIPCS) may be viewed at http://www.vipcs.org.

Contributor Information

Lorri Zipperer, Email: lorri@zpm1.com.

Jan Sykes, Email: jansykes@ameritech.net.

REFERENCES

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, and Donaldson MS. eds.To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine. Keeping patients safe: transforming the work environment of nurses. Washington, DC: The Institute, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Data Standards for Patient Safety, Institute of Medicine. Achieving a new standard of care. Washington, DC: The Institute, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Patient Safety Foundation. Public opinion of patient safety issues: research findings. [Web document]. Chicago, IL: National Patient Safety Foundation, 1997. [cited 17 Jun 2004]. <http://www.npsf.org/download/1997survey.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton JA, Helmreich R, Provanost PJ, and Thomas E. Safety climate survey. 2003. Austin, TX: The Center of Excellence for Patient Safety Research & Practice, University of Texas. [cited 17 Jun 2004]. <http://www.qualityhealthcare.org/IHI/Topics/PatientSafety/MedicationSystems/Tools/Safety+Climate+Survey+%28IHI+Tool%29.htm>. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Safe Medication Practice. 2004 ISMP medication safety self-assessment for hospitals. [Web document]. Huntingdon Valley, PA: The Institute, May 2004. [cited 17 Jun 2004]. <http://www.ismp.org/Survey/>. [Google Scholar]

- Benchmarking Network, Medical Library Association. Single institution profile data. [Web document]. Chicago, IL: The Association. [cited 17 Jun 2004]. <http://www.mlanet.org/members/benchmark/worksheet_2003–04.html#3>. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DJ, Hodgett RA. Why executives don't respond to your survey. Adelaide, Australia: School of Accounting & Information Systems, University of South Australia, 1999. [cited 17 Jun 2004]. <http://www.vuw.ac.nz/acis99/Papers/PaperHodgett-060.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Gawande A. When doctors make mistakes. In: Gawande A. Complications: a surgeon's notes on an imperfect science. New York, NY: Henry Holt, 2002:47–74. [Google Scholar]