ABSTRACT

One's history of infections can affect the immune response to unrelated pathogens and influence disease outcome through the process of heterologous immunity. This can occur after acute viral infections, such as infections with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) and vaccinia virus, where the pathogens are cleared, but it becomes a more complex issue in the context of persistent infections. In this study, murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) was used as a persistent infection model to study heterologous immunity with LCMV. If mice were previously immune to LCMV and then infected with MCMV (LCMV+MCMV), they had more severe immunopathology, enhanced viral burden in multiple organs, and suppression of MCMV-specific T cell memory inflation. MCMV infection initially reduced the numbers of LCMV-specific memory T cells, but continued MCMV persistence did not further erode memory T cells specific to LCMV. When MCMV infection was given first (MCMV+LCMV), the magnitude of the acute T cell response to LCMV declined with age though this age-dependent decline was not dependent on MCMV. However, some of these MCMV persistently infected mice with acute LCMV infection (7 of 36) developed a robust immunodominant CD8 T cell response apparently cross-reactive between a newly defined putative MCMV epitope sequence, M57727–734, and the normally subdominant LCMV epitope L2062–2069, indicating a profound private specificity effect in heterologous immunity between these two viruses. These results further illustrate how a history of an acute or a persistent virus infection can substantially influence the immune responses and immune pathology associated with acute or persistent infections with an unrelated virus.

IMPORTANCE This study extends our understanding of heterologous immunity in the context of persistent viral infection. The phenomenon has been studied mostly with viruses such as LCMV that are cleared, but the situation can be more complex with a persistent virus such as MCMV. We found that the history of LCMV infection intensifies MCMV immunopathology, enhances MCMV burden in multiple organs, and suppresses MCMV-specific T cell memory inflation. In the reverse infection sequence, we show that some of the long-term MCMV-immune mice mount a robust CD8 T cell cross-reactive response between a newly defined putative MCMV epitope sequence and a normally subdominant LCMV epitope. These results further illustrate how a history of infection can substantially influence the immune responses and immune pathology associated with infections with an unrelated virus.

KEYWORDS: CD8 T cell, memory inflation, heterologous immunity, cross-reactivity, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, murine cytomegalovirus, mouse

INTRODUCTION

Heterologous immunity, that is, the ability of immunological memory specific to one pathogen to contribute to the control of a different pathogen, has been an established immunological phenomenon since Edward Jenner used cowpox virus to immunize against variola virus, the cause of human smallpox. Originally appreciated for its significance among closely related viruses, such as between influenza A virus variants (1), where it has been called heterotypic immunity, or between dengue virus serotypes (2, 3), where the phenomenon of immune enhancement of pathogenesis was originally defined, it has become clear that heterologous immunity can be either beneficial or detrimental to the host. What is less explored yet becoming increasingly clear is that heterologous immunity between completely unrelated pathogens exists. Heterologous immunity can be mediated by T cells or antibodies cross-reactive between unrelated pathogens or possibly by antiviral or immunologically active cytokines in a less specific manner (4).

T cells can mediate heterologous immunity by several mechanisms, including (i) by their propensity to have degenerative specificity and be cross-reactive against peptide epitopes encoded by different pathogens (4), (ii) by their ability to secrete broadly reactive antimicrobial cytokines such as gamma interferon (IFN-γ) when stimulated by a cognate antigen (5, 6), and (iii) by the ability of inflammatory cytokines to relatively nonspecifically activate preformed memory T cells into effector cells (7, 8).

Memory CD8 T cells established after an infection are usually stably maintained by homeostatic proliferation (9–12) and can influence the host's immune response to subsequent infections. During heterologous infections, however, the number of the preexisting memory CD8 T cells specific to previously encountered pathogens is changed in that there is a type I IFN-induced apoptosis and attrition of memory cells that reduce their overall numbers (10, 13–18). An exception to that phenomenon occurs if the second pathogen is a poor type I IFN inducer or if there is T cell cross-reactivity between the two pathogens. In the latter case there can be a substantial increase in the number of cross-reactive T cells, as has been shown clearly in several animal model systems (19–21). Notably, since the memory T cell pools even of genetically identical hosts have wide variations in their T cell receptor (TCR) usage, there can be high variability in the quality and quantity of the cross-reactive responses as well as in the pathogenic outcome. This is referred to as the private specificity of the memory cell response (22–25).

Cytomegaloviruses (CMVs) are ubiquitous host-specific pathogens that have adapted to their hosts through evolution. CMVs from different species have co-opted and mutated host cell genes in ways that resulted in these viruses having much of their genetic machinery devoted to antagonizing immune system function. Further, probably because of the nature of their persistence, CMVs play by different rules in regard to the stability of T cell memory. Instead of maintaining constant or declining levels of memory CD8 T cells, there is memory inflation, where T cell responses against certain epitopes increase in number over time. In humans, monkeys, and mice, CMV-specific T cells can in some cases reach unusually high frequencies, particularly in older individuals (26–31).

Murine CMV (MCMV) causes persistent infections in mice, and this has been a useful model system for studying CMV infections in humans. One of the hallmarks of MCMV infection, like that of human CMV, is T cell memory inflation, beyond the initial expansion and contraction of responding T cell populations (26–28). Heterologous immunity has been studied mostly in the mouse with completely resolving acute viral infections, with little emphasis on what happens during persistent infections. Here, we use the very well-defined lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), strain Armstrong, to probe questions about heterologous T cell-dependent immunity with persistent MCMV infection. This is examined in both directions, with MCMV either as the first virus infection (MCMV+LCMV) or as the second virus infection (LCMV+MCMV). We question whether there is altered memory T cell stability, cross-protective immunity, altered pathogenesis, and evidence of T cell cross-reactivity, and we find many alterations in these phenomena. Notably, there is a very strong private specificity phenomenon whereby some, but not all, mice have a dramatically elevated T cell response apparently cross-reactive between the two viruses.

RESULTS

LCMV+MCMV: MCMV causes an acute reduction of but does not continue to erode numbers of LCMV-specific memory cells.

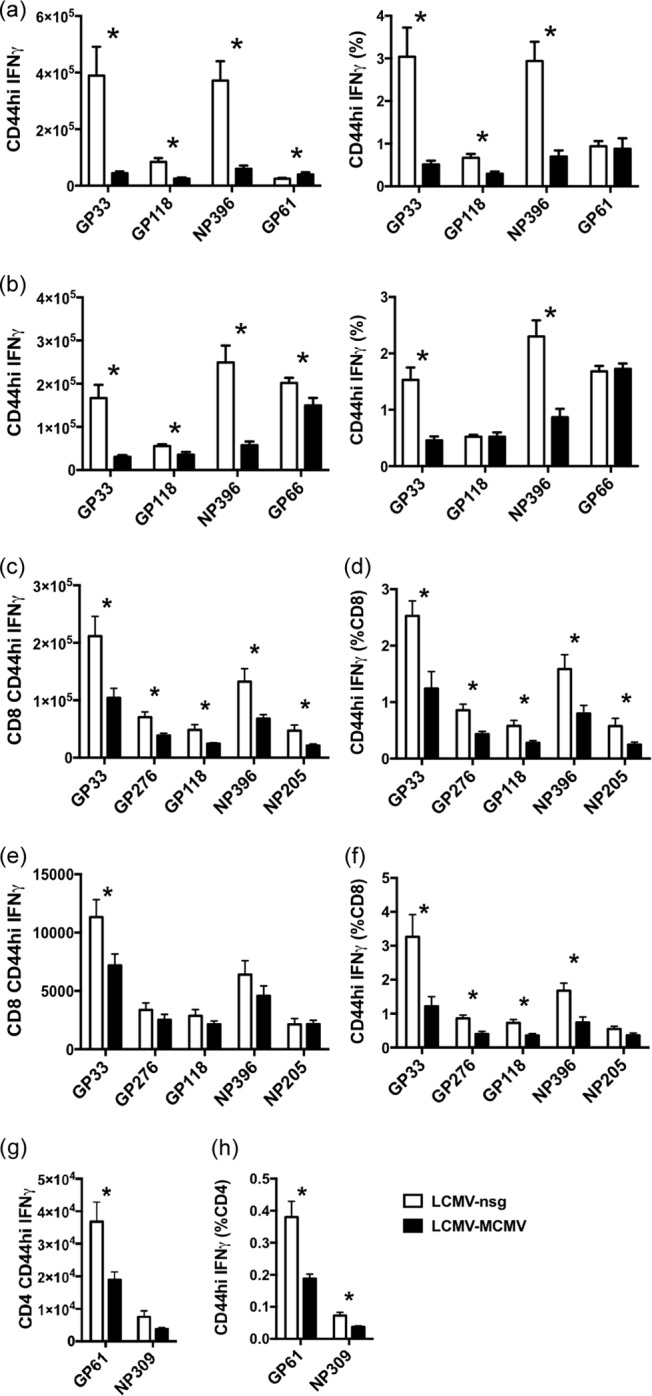

The peak of virus-induced type I IFN levels coincides with the apoptotic attrition of CD44hi CD8 memory T cells early during many viral infections, and other memory cells leave the spleen and lymph nodes to migrate to peripheral tissues (16, 32). MCMV induces an early type I IFN response (33), and a previous study used the older limiting dilution assay technique to show that MCMV infection reduced memory CD8 T cell precursor frequencies to LCMV (10). In the present study, to examine with more quantitative intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assays the effect of MCMV infection on preexisting memory CD8 and CD4 T cells, LCMV-immune C57BL/6 mice were inoculated with 5 × 105 PFU of a diluted MCMV salivary gland stock intraperitoneally (i.p.) or injected with a comparably prepared diluted salivary gland homogenate from naive animals (naive salivary gland [nsg]) as a sham control. We first confirmed the expected result that MCMV would cause an attrition of LCMV-specific memory T cells early (day 4) after acute MCMV infection. Figure 1a shows by ICS that MCMV infection caused a reduction in the total number (left) and percentage (right) of CD8 memory T cells specific to the LCMV class 1 major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-presented epitopes GP33–41, NP396–404, and GP118–125. There also was a less dramatic reduction in CD4 memory T cells specific to the class II MHC-presented epitope, GP61–80. Figure 1b shows nearly identical results using class I and class II MHC tetramers to quantify the memory T cells. The tetramer data show that the loss in memory T cells is real and not a consequence of impaired cytokine production in an ICS assay as a consequence of T cell dysfunction. This expected result showed that, like other virus infections, MCMV infection will cause reductions in memory cell frequencies as measured by both functional and physical approaches.

FIG 1.

MCMV infection significantly reduces the number and frequency of LCMV-specific memory CD8 and CD4 T cells at 4 days (a and b) and 9 weeks (c to h) after MCMV inoculation. LCMV-immune mice were infected i.p. with 5 × 105 PFU of MCMV or given salivary gland homogenate from naive mice (nsg) as controls. Memory CD8 and CD4 T cells from spleens were examined at day 4 post-MCMV infection by ICS (a) and tetramer staining (b). Memory CD8 T cells from spleens (c and d) and bone marrow (e and f) and memory CD4 T cells from spleens (g and h) were examined at 9 weeks post-MCMV infection by ICS. The phenomenon of LCMV-specific memory reduction was observed in two other similarly designed experiments in cells harvested at 6 and 24 weeks after MCMV infection. *, P < 0.05, for results in the MCMV-infected group compared to those in the nsg-treated sham control group (n = 5).

The focus of the recent study, however, was to evaluate the long-term effects of MCMV persistent infection on LCMV memory responses, as well as the effect of immunity to LCMV on long-term MCMV memory responses. Figure 1c to f show in a separate experiment that, compared to the LCMV-immune mice without MCMV infection, splenic memory CD8 T cells specific for LCMV immunodominant epitopes GP33–41 and NP396–404 and subdominant epitopes GP276–286, GP118–125, and NP205–212 were significantly reduced in both the total number and percentage of CD8 T cells at 9 weeks post-MCMV infection (Fig. 1c and d). Some reports have indicated that memory T cells may accumulate in the bone marrow (34, 35), but data in Fig. 1e and f show reductions in the percentage of LCMV-specific memory cells in the bone marrow as well. Due to the low and variable numbers of cells collected and the rarity of T cells in the bone marrow, the reduction in total numbers was statistically significant only for the GP33–41-specific memory CD8 T cells. However, the decreases in the percentages of memory CD8 T cells of other specificities were statistically significant in the bone marrow (Fig. 1f), and these experiments clearly show that the loss of memory T cells from the spleen could not be accounted for by migration to the bone marrow. Long-term persistent MCMV infection also significantly reduced the memory CD4 T cell population in the spleen, resulting in about a 50% reduction in number and in frequency of GP61–80-specific memory CD4 T cells (Fig. 1g and 1 h). The percentage of NP309–328-specific CD4 T cells was also significantly reduced in the spleen (Fig. 1h). In these long-term persistence studies, we primarily relied on the functional ICS assays to monitor memory cells, but the possibility existed that the reduction in memory cell frequencies might have been due to functional exhaustion rather than deletion. However, there was no indication of any cellular exhaustion. Cells undergoing exhaustion would produce lower levels of cytokines and would first lose their abilities to produce tumor necrosis factor (TNF) (36, 37). Using mean fluorescence intensities as a quantitative indicator of cytokine production, we found little difference in the levels of TNF and IFN-γ in LCMV-specific memory cells, whether or not the mice were MCMV infected, and the ratios of TNF to IFN-γ production were high in memory cells from both sets of mice (data not shown). Further, more limited studies with NP396–404, GP33–41, GP118–125, and GP66–77 tetramers at day 4 (Fig. 1a and b) and week 4 postinfection showed similar losses in memory T cell numbers in the spleen whether ICS or tetramer assays were used, even though the efficiencies of the techniques were not identical. In a comparison of LCMV+nsg versus LCMV+MCMV infections at week 4, the percentages of CD8 T cells specific for NP396–404 were 4.8% ± 0.6% versus 1.2% ± 0.2%, by ICS assay and 1.3% ± 0.1% versus 0.32% ± 0.04%, by tetramer staining; the percentages of CD4 T cells specific for GP61–80 were 1.2% ± 0.09% versus 0.57% ± 0.07%, by ICS assay, and 1.2% ± 0.03% versus 0.7% ± 0.05% by GP66–77 tetramer staining (n = 4).

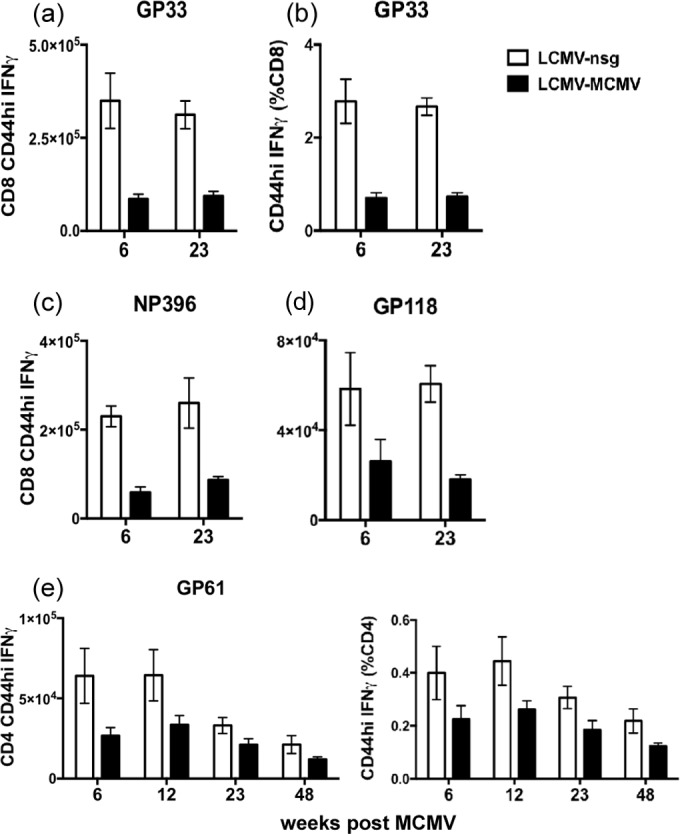

The MCMV persistent infection in mice results in a continual presentation of viral antigen and a sporadic proliferation of CD8 T cells, resulting in inflationary memory T cell responses to certain MCMV epitopes (28, 38–40). In C57BL/6 mice the most vigorous inflation of memory T cells happens between 8 and 12 weeks post-MCMV inoculation (38). We questioned whether this inflation of MCMV-specific T cells would compete with the preexisting LCMV-specific memory T cells for space and cytokines and lead to a passive reduction of preexisting LCMV-specific memory cells. In a separate long-term experiment, LCMV-immune mice inoculated with MCMV or with control salivary gland homogenates were harvested for splenocytes at different time points during the long-term persistent infection to check the number and frequency of LCMV-specific memory T cells as a function of time of persistence (Fig. 2). As shown above in Fig. 1, MCMV infection caused a reduction of both CD8 and CD4 memory T cells. However, apart from the initial attrition that happened early during infection, no further significant reduction of LCMV-specific memory CD8 T cells was found between 6 and 23 weeks post-MCMV infection (Fig. 2a to d). Similarly, memory CD4 T cells were not further eroded by MCMV persistence (Fig. 2e). After the initial period of early attrition of memory cells, the memory LCMV-specific CD4 T cell number tended to gradually erode over time even in non-MCMV-infected mice and started to decline at the same time and in a similar fashion.

FIG 2.

MCMV persistence does not further erode LCMV-specific memory CD8 or CD4 T cells (LCMV+MCMV). LCMV-immune mice were infected i.p. with 5 × 105 PFU of MCMV or given salivary gland homogenate from naive mice as controls. Memory CD8 T cells specific for GP33–41, NP396–404, and GP118–125, (a to d) and memory CD4 T cells specific for GP61–80 from the spleen (e) were examined at weeks 6, 12, 23, and 48 post-MCMV infection by ICS (n = 5). The complete experiment was done once, but a similar observation was made in a separate experiment in cells harvested at weeks 9 and 24 post-MCMV inoculation.

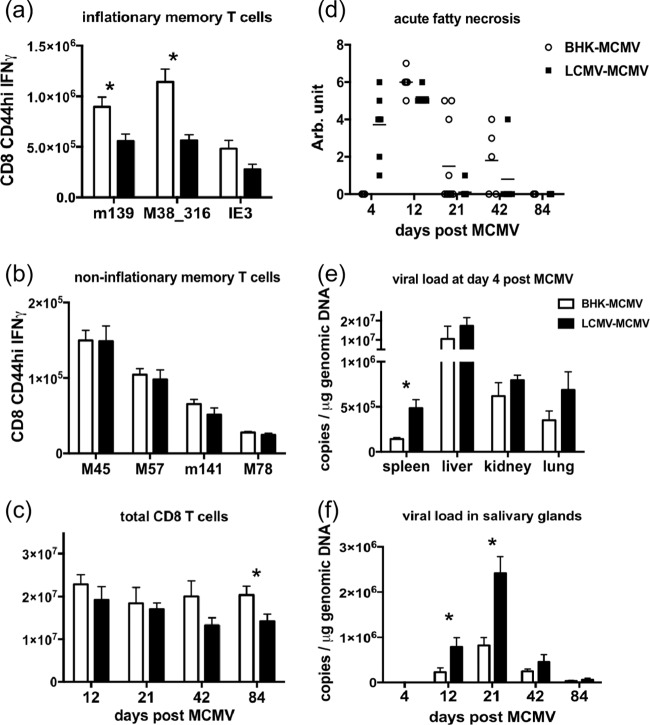

LCMV+MCMV: history of LCMV infection reduces MCMV-specific memory T cell inflation.

MCMV-specific memory CD8 T cells have distinct expansion and contraction patterns, with some of them inflationary and increasing in number from 8 to 12 weeks of MCMV infection (28, 38). To examine the effect of the history of LCMV infection on T cell responses to MCMV infection and the subsequent inflationary T cell memory generation, LCMV-immune mice and control mice inoculated with vehicle (baby hamster kidney [BHK] cell supernatant) were inoculated with MCMV, and then the MCMV-specific CD8 T cells in the spleen were analyzed by ICS after in vitro peptide stimulation. After the period of memory inflation at week 12 post-MCMV infection, the numbers of inflationary memory CD8 T cells specific for the previously defined inflationary epitopes m139419–426, M38316–323, and IE3416–423 were lower in the LCMV-immune mice than in nonimmune controls (Fig. 3a). The number of M38316–323-specific memory CD8 T cells presented with the most consistent inflationary pattern in BHK supernatant-treated control mice across repeated experiments, but this inflation was inhibited in the LCMV-immune mice. No differences were found in the number of noninflationary memory T cells between the LCMV-immune and the BHK control groups at 12 weeks postinfection (Fig. 3b). The suppressed memory inflation was also evident in the total number of CD8 T cells accumulated in the spleen over time. The total number of CD8 T cells was significantly higher in the BHK control group than in the LCMV-immune group at 12 weeks post-MCMV infection (Fig. 3c). Total antigen-experienced CD44hi CD8 T cells (regardless of specificity) also accumulated to higher numbers in the BHK control group than the LCMV-immune group at 12 weeks post-MCMV infection (average, 10 × 106 ± 1.3 × 106 cells in BHK controls versus 7.3 × 106 ± 0.96 × 106 cells in the LCMV-immune group; P = 0.089). Ironically, in the section above we had originally wanted to test whether MCMV memory inflation would compete against LCMV-specific memory T cells, but that question could not be resolved because, paradoxically, the history of LCMV infection prevented MCMV-specific memory inflation.

FIG 3.

A history of LCMV infection suppresses the generation of MCMV-specific inflationary memory T cells, alters immunopathology, and weakens viral control of MCMV infection (LCMV+MCMV). LCMV-immune C57BL/6 mice and BHK supernatant-treated controls were infected with 5 × 105 PFU of MCMV. (a and b) MCMV-specific inflationary and noninflationary memory CD8 T cells in the spleens were examined by ICS after in vitro peptide stimulation at week 12 (day 84) postinfection. (c) Total CD8 T cells were also enumerated at days 12, 21, 42, and 84 postinfection. (d) The necrosis in the fat pad was measured on a scale of 0 to 7 as published previously (6): 1 to 2 indicates mild disease with only a few spots on the lower abdominal fat pad, 3 to 4 indicates moderate disease with larger white patches extending out to the upper quadrant of the fat pad, 5 to 6 indicates more severe disease with infiltration of inflammatory cells throughout the fat pad, and 7 indicates that the organs are sticking together. (e and f) MCMV copy number was measured by qPCR on DNA extracted from snap-frozen spleen, liver, kidney, and lung on day 4 postinfection and from salivary glands on days 4, 12, 21, 42, and 84 postinfection, as indicated. The complete experiment was done once. Viral burden and acute fatty necrosis scores on days 4 and 21 are representative of data in two other separate experiments. The analysis of memory T cells at weeks 3, 6, and 12 (days 21, 42, and 84, respectively) is representative of data in three other separate experiments. *, P < 0.05, for results in the LCMV-immune group compared to those in the BHK control group (n = 5). Arb, arbitrary.

LCMV+MCMV: history of LCMV infection alters the pathology and viral load during MCMV infection.

To study the effect of heterologous immunity on the pathogenesis of MCMV infection, LCMV-immune mice and the BHK supernatant-treated controls were inoculated with MCMV and then examined at days 4, 12, 21, 42, and 84 postinfection. When mice were inoculated intraperitoneally, the proximal fat in the lower abdomen became infected, inflamed, and necrotic. The extent of necrosis can be visually scored based on a previously established scale, as described in Materials and Methods (6). On day 4 post-MCMV inoculation, LCMV-immune mice had severe necrosis in the fat pads while the sham-immune control mice showed no sign of immunopathology (Fig. 3d). In contrast, necrosis was severe in both LCMV-immune and sham-immune control groups at day 12 post-MCMV infection, which is shortly after the peak of the T cell response. By day 21 most of the necrosis was resolved in the LCMV-immune mice, but prolonged necrosis was observed in some of the BHK control animals. Therefore, the history of LCMV infection influences the severity and the duration of immunopathology during MCMV infection by enhancing pathology early and inhibiting it at later stages after MCMV challenge.

MCMV disseminates through mononuclear phagocytes (41) to target organs during the acute phase of infection. Productive infection is cleared quickly except from the salivary glands (42), where viral burden peaks at about day 21 and lasts for weeks. Upon the development of latency, viral DNA can be detected in macrophages and in endothelial cells in various organs (43, 44). To evaluate the effect of the history of LCMV infection on virus control, MCMV viral copy number in DNA extracted from snap-frozen solid organs was measured by quantitative PCR (qPCR) using MCMV glycoprotein B (gB) primers for MCMV and mouse β-actin primers for the mouse genome. At day 4 post-MCMV infection, more MCMV viral copies per microgram of genomic DNA were found in the spleen, liver, kidney, and lung of LCMV-immune mice than in the organs of the nonimmune mice (Fig. 3e). In one experiment where PFU titers were assessed by plaque assay as described previously (45), the liver of LCMV-immune mice had a 0.6-log-higher MCMV PFU titer (average, 4.5 ± 0.15 in LCMV-immune versus 3.9 ± 0.23 in BHK control mice; P = 0.067; n = 5). As expected, MCMV was not detected in the salivary gland for the first few days, and the MCMV copy numbers in salivary glands from both groups peaked on day 21 post-MCMV infection (Fig. 3f). MCMV load in the salivary glands of the LCMV-immune mice was higher than that in the BHK control mice throughout the experiment (Fig. 3f). Therefore, the history of LCMV infection enhanced MCMV viral burden during MCMV infection. This is a common characteristic of heterologous immunity, which can be either beneficial or detrimental and which can result in either inhibition or enhancement of the challenge virus load (4).

MCMV+LCMV: decline in acute LCMV-specific T cell response in aging mice unrelated to the history of MCMV infection.

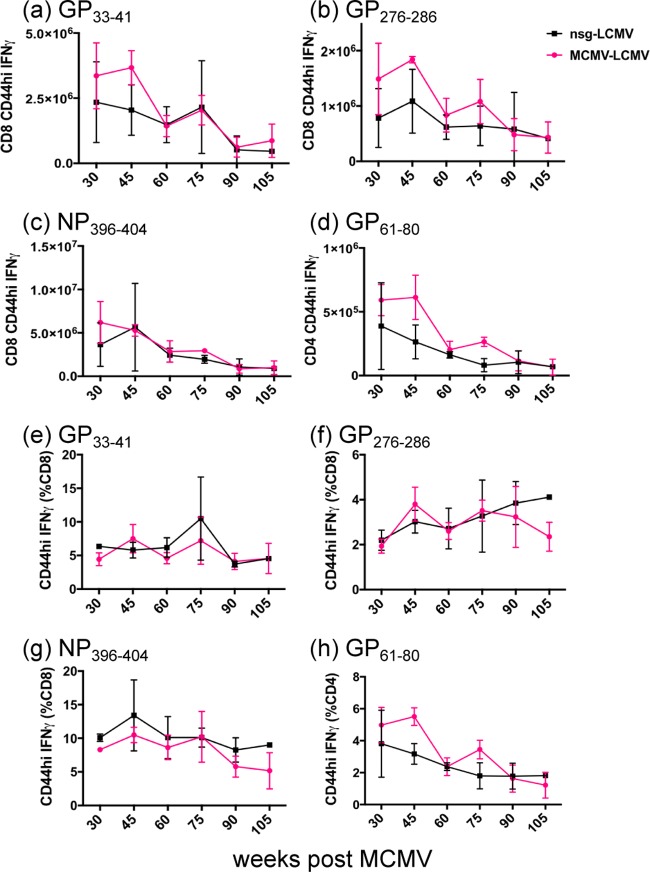

We next reversed the order of the virus inoculations to determine whether a history of MCMV infection may affect the immune response to a subsequently acquired heterologous virus, LCMV. Mice inoculated with MCMV or the nsg-treated sham controls were subsequently infected with LCMV at weeks 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 91, 105, 120, and 130 post-MCMV infection. As expected, the magnitude of the peptide-specific T cell response to LCMV at day 8 post-LCMV infection trended downward with age, especially after week 60 of persistent MCMV infection, presumably due to a well-documented immunosenescence process (46–48). However, the LCMV-specific response was not dramatically different between the long-term MCMV-immune mice and the nsg-treated controls (Fig. 4a to d). Over time the percentages of the responses to CD8 peptides GP33–41, GP276–286, and NP396–404 did not decline as much as the percentages of the response to the CD4 peptide GP61–80 (Fig. 4e to h), but that also was unrelated to the MCMV infection. We conclude that persistent MCMV infection did not contribute to the immunosenescence and reduced immune response to LCMV challenge as the animals aged.

FIG 4.

The magnitude of T cell responses to acute LCMV infection declines with age whether or not mice were previously infected with MCMV (MCMV+LCMV). Mice at 6 weeks of age were inoculated with MCMV or injected with naive salivary gland homogenate. MCMV-immune and nsg-treated control mice were infected with 5 × 104 PFU of LCMV at multiple different time points post-MCMV infection and analyzed at day 8 after LCMV infection by ICS. The total number and frequency of CD8 T cell responses to GP33–41 (a and e), GP276–286 (b and f), and NP396–404 (c and g) and CD4 T cell responses to GP61–80 (d and h) are shown with means and SEM (n = 3). The entire long-term immune experiment was done once, but similar observations were made in experiments with separately inoculated 29-week, 80-week, and 120-week MCMV-immune mice.

Potential cross-reactivity between MCMV and LCMV.

T cells recognizing peptide epitopes encoded by one pathogen sometimes cross-react with epitopes encoded by another unrelated pathogen, and this reactivity can be a cause of heterologous immunity (4). This was examined in infections with the viruses in either order.

LCMV+MCMV.

To examine whether cross-reactive epitopes existed between LCMV and MCMV, splenocytes from LCMV-immune mice and the BHK controls were examined at day 8 post-MCMV infection (LCMV+MCMV) by ICS after in vitro stimulation with 20 different MCMV and LCMV peptides separately (49). Despite some variability between experiments, no substantial and repeatable cross-reactive response was identified with this sequence of infections, as indicated by qualitative changes in responses in MCMV-challenged LCMV-immune hosts. Thus, the history of LCMV infection had no dramatic effect on the magnitude or the hierarchy of the CD8 T cell response to MCMV epitopes on day 8 postinfection (data not shown), despite the fact that the history of LCMV infection seemed to ultimately suppress the MCMV T cell response to inflationary epitopes later on (Fig. 3a). Surprisingly, the higher MCMV burden among LCMV-immune mice did not seem to increase the magnitude of the CD8 T cell response to MCMV.

MCMV+LCMV.

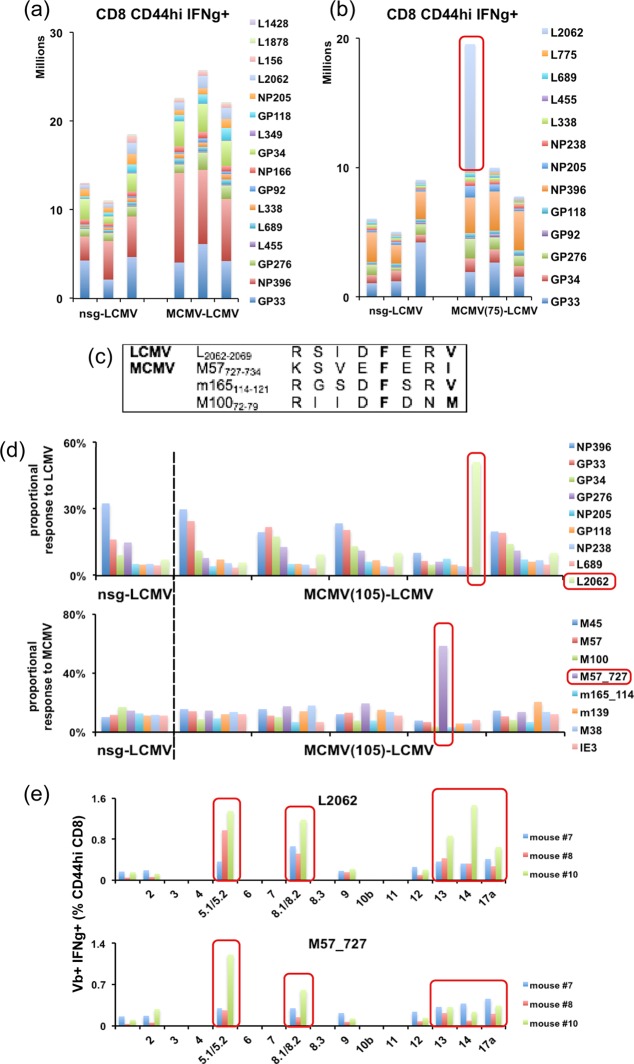

The reciprocal experiment with MCMV-immune and nsg-treated sham control mice challenged with LCMV resulted in a somewhat different outcome. Eight days after infection with LCMV, splenocytes were stimulated with 16 different peptides separately in an ICS assay (50). LCMV infection induced a robust response of a higher overall magnitude in the 6-week MCMV-immune mice (Fig. 5a). The responses to LCMV NP396–404, L689–697, and L338–346 were significantly greater in the MCMV-immune mice than in the nsg-treated controls. A provocative result was found when mice at 30 weeks or longer post-MCMV infection were inoculated with LCMV. Several (7 out of 36) mice displayed a dramatically elevated response to the normally subdominant LCMV-encoded peptide L2062–2069: for the seven mice, 15.7%, 21.4%, 6.9%, 12.4%, 4.4%, 6%, and 2.5% of CD8 T cells were responsive to L2062–2069, compared to normally only 1 to 2% or less responding. In about one in every five MCMV-immune mice, the hierarchy of the epitope response to LCMV was altered, and sometimes nearly half of the LCMV-specific response could be accounted for as specific to L2062–2069 (Fig. 5b). This responsiveness was seen in six completely separate experiments.

FIG 5.

Infecting long-term MCMV-immune mice with LCMV (MCMV+LCMV) identifies a new MCMV epitope, M57727–734, that is probably cross-reactive to LCMV L2062–2069. (a) MCMV-6-week-immune mice and age-matched nsg-treated controls were infected with 5 × 104 PFU LCMV. Splenocytes were analyzed by ICS at day 8 postinfection. Each vertical bar represents one mouse. Data represent one of two similar experiments. (b) MCMV-75-week-immune mice and nsg-treated controls were analyzed at 8 days after LCMV infection by ICS. (c) Three MCMV peptides with sequence homology to L2062–2069 were chosen for experiments. (d) Five 105-week MCMV-immune mice and one nsg-treated control mouse were analyzed at 8 days after LCMV infection by ICS. About 50% of the major LCMV-specific response was found specific for L2062–2069 in the same mouse that showed over 50% of the major MCMV-specific response specific for M57727–734. (e) MCMV-120-week-immune (mouse 8 and 10) and nsg-treated control (mouse 7) mice were analyzed at day 9 post-LCMV infection by ICS. A putative cross-reactive response between L2062–2069 and M57727–734 was observed in mouse 10. The frequencies of IFN-γ- and Vβ-positive T cells (percentage of CD8 CD44hi T cells) were compared by different Vβ chains in each mouse. Cross-reactivity was observed at different time points in the initial long-term experiment, and hence a separate group of long-term MCMV-immune mice was examined at additional time points for cross-reactive responses after LCMV infection.

L2062–2069 is a Kb-restricted epitope (50). Using a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) search against the MCMV protein sequence, 14 MCMV peptide sequences with substantial homology to the original L2062–2069 sequence and 28 sequences with homology to its variations (where the anchor positions p5 and p8 were replaced by structurally similar residues) were identified. Two MCMV peptides not previously defined as epitopes, M57727–734 and m165114–121, with a SYFPEITHI score of 19 and 20, respectively, predictive of good MHC class I binding capacity, were synthesized and tested along with a known MCMV epitope, M10072–79 (Fig. 5c), by ICS at day 8 post-LCMV infection. MCMV-immune mice bearing an elevated response to L2062–2069 responded to M57727–734 with a response of similar magnitude and with an altered proportional response hierarchy (Fig. 5d), suggesting cross-reactivity in the CD8 T cell responses between M57727–734 and L2062–2069 epitopes. In contrast, no response was raised against m165114–121.

To determine if these putative cross-reactive epitopes were recognized by the same subset of TCR clones, TCR Vβ chain usage of L2062–2069- and M57727–734-specific T cells was analyzed in one nsg-treated control mouse (where the response was not amplified) and in two MCMV-immune mice at day 9 of infection with LCMV at week 120 post-MCMV infection in which the putative cross-reactive response was amplified in one mouse (mouse 10). Both M57727–734- and L2062–2069-specific T cells preferentially used the Vβ5.1/5.2 and Vβ8.1/8.2 chains. L2062–2069-specific T cells additionally used Vβ13, Vβ14, and Vβ17a (Fig. 5e). We suggest that the shared Vβ families as seen in mouse 10 may contain cross-reactive TCR clone(s).

DISCUSSION

These studies explored different aspects of heterologous immunity in LCMV-immune mice challenged with MCMV (LCMV+MCMV) and in MCMV-immune mice challenged with LCMV (MCMV+LCMV). Clearly, the history of the previous infection altered the pathogenesis and/or immune response to the subsequent infection. We chose to investigate these two viruses because LCMV (Armstrong strain) induces an acute infection that is completely cleared from the host, whereas MCMV causes a low-grade persistent infection associated with latency and sporadic viral synthesis. The T cell responses to these two pathogens are highly defined yet distinct in their progressions in that LCMV forms stable memory in the absence of subsequent infections (9, 10), but MCMV forms inflationary memory to certain distinct epitopes (28, 38). Although some other studies have explored heterologous immunity between unrelated viruses, the nature of the immune response to the persistent MCMV infection makes this study novel.

A history of LCMV infection altered the pathogenesis of the MCMV infection (LCMV+MCMV) in regard to the kinetics of immune pathology at the site of inoculation and to the elevation of viral load throughout the host. Although there was no dramatic effect on the overall acute MCMV T cell response, the history of LCMV infection surprisingly, especially in light of the increased MCMV titers, inhibited the inflationary CD8 T cell response to MCMV epitopes during the persistent MCMV infection. We have no explanation for that finding, but it was highly reproducible in three separate experiments. As expected, the acute MCMV infection caused a reduction in the frequency and number of LCMV-specific memory T cells, probably as a consequence of the well-defined type I IFN-induced apoptosis of memory cells early during many infections (10, 13–18); indeed, we confirmed that there was a substantial very early loss of memory CD8 T cells in this study (Fig. 1a and b). However, continued MCMV infection caused no further decline in LCMV-specific memory T cells.

A history of persistent MCMV infection usually did not substantially alter the acute T cell response to LCMV (MCMV+LCMV), and although the acute response to LCMV declined with the age of the host, reflecting immune senescence, whether the host was infected with MCMV seemed to play little role in the process. However, about 20% of the time, that is, in 7 of 36 mice, encompassing eight experiments, an immunodominant, presumably cross-reactive T cell response was detected against a normally subdominant LCMV epitope, L2062–2069, and an MCMV peptide sequence, M57727–734, not previously defined as an epitope. These responses were weak in mice infected with either virus alone (with 0.1 to 0.2% CD8 T cells being M57727–734 specific on day 8 post-MCMV infection; n = 3) yet dramatic in a reproducible subset of sequentially infected mice, illustrating the impact of the private specificity of T cell responses in the context of heterologous immunity.

Infection with MCMV resulted in the reduction of preexisting LCMV-specific memory CD8 and CD4 T cells by about 50% (Fig. 1). This is consistent with the published data on memory CD8 T cells and their type I IFN-induced apoptosis that occurs early in infections (10, 13–19, 51). Early on, some of this loss is also due to migration and redistribution of memory T cells, but our data here show that there is still a loss even when the immune system is in more of a steady state during persistent infection. This seems to be part of the normal homeostasis process, and it is unlikely that a 50% reduction in these high frequencies of memory cells would cause a loss in immunity. However, experiments have shown that repeated infections can drive memory cell attrition to a point where resistance to infection is reduced (51). Long-term persistence of MCMV, however, did not continue to erode preexisting T cell memory to LCMV. We originally hypothesized that persistent MCMV infection by way of the constant activation and proliferation of inflationary memory T cells might cause a reduction of preexisting LCMV-specific memory cells due to competition between memory cell populations. Surprisingly, there was very little inflation of MCMV-specific memory cells in LCMV-immune mice, foiling any testing of that original hypothesis. Interestingly, in human studies when two persistent virus infections are present, it has been shown that the CMV responses may inhibit the inflation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific CD8 T cell memory responses (30). The magnitude of the EBV-specific response measured by tetramer staining in CMV-seronegative donors increases with age, but the responses are comparable between the aged and the young CMV-seropositive donors.

Although the acute MCMV challenge initially reduced the numbers of LCMV-specific cells, the history of LCMV infection (LCMV+MCMV) (i) caused more severe panniculitis early during MCMV infection, (ii) enhanced MCMV burden, and (iii) reduced MCMV-specific T cell memory inflation. The more severe panniculitis may not be a surprise early after MCMV infection in LCMV-immune mice since a similar immunopathology has been observed after vaccinia virus infection of LCMV-immune mice (6, 52, 53). The severe panniculitis seen in LCMV-immune mice infected with vaccinia virus has been linked to cross-reactive T cell responses, but the mechanisms here with MCMV have not yet been resolved. Higher MCMV viral DNA loads were observed in the spleen, liver, kidney, lung, and salivary glands in the LCMV-immune mice. Nearly 20 years ago, an examination of heterologous immunoprotection by plaque assay showed that immunity to LCMV was slightly protective against MCMV (6), but the present study used different stocks of MCMV with different virulence properties; and our experience has shown that the outcome of heterologous immunity can sometimes be viral strain, variant, dose, and stock dependent, and also that the pathogenesis of MCMV can change dramatically between different salivary gland stocks.

Higher MCMV titers early during infection were expected to enhance memory inflation because more target cells would have been seeded with latent MCMV, thereby creating a larger reservoir of infected targets presenting antigens to inflationary T cells. However, the number of inflationary MCMV-specific memory CD8 T cells was reduced in the LCMV-immune mice. The percentages of lymphocytes that were CD8 T cells were steadily maintained in both groups at about 20% throughout the study, but the number of CD8 T cells and the number of CD44hi CD8 T cells were lower in the LCMV-immune group. We do not have an explanation for these very reproducible findings.

In this study, the long-term MCMV-immune mice generated CD8 and CD4 T cell responses to LCMV at levels comparable to those of the age-matched nsg-treated control mice. There was a decline in acute T cell responses to LCMV over time in both groups, and this is consistent with the phenomenon of immune senescence (47, 54). A recent study showed that aged mice previously inoculated with the MCMV deletion mutant MCMV-Δ157, which lacks the ligand for NK cell-activating receptor Ly49H, are impaired in the GP33–41- and NP396–404-specific CD8 T cell responses to LCMV infection, resulting in a higher LCMV viral load than that in the aged-matched controls (55). MCMV-Δ157 infection is not as well controlled as wild-type MCMV infection in C57BL/6 mice, resulting in a much higher initial viral burden (56). Perhaps enhanced pathogenesis by this mutant virus resulted in a greater immunosuppressive effect than that seen with the wild-type virus in our study. Furthermore, MCMV did not seem to intensify the effect of immune senescence in aged mice in our study, and this argues against the emerging suggestions that CMV latency contributes to immune senescence (46, 57–59). Two recent transcriptomic studies also find separation between the effects of CMV and aging on the immune system. One study found that only one-fifth of the canonical pathways affected by aging overlap the pathways affected by CMV latent infection (60), and another study using a systems biology approach on expression data from influenza-vaccinated subjects showed negligible effects of CMV latency on the immune system among elderly participants (61).

In the long-term MCMV-immune mice acutely infected with LCMV, a new MCMV epitope sequence, M57727–734, was found to possibly cross-react with LCMV L2062–2069 as T cell frequencies to these two peptides were nearly identical. These two sequences are the first putative cross-reactive epitope pair identified between LCMV and MCMV. M57727–734 shares 50% sequence homology with L2062–2069. The other amino acids are biochemically similar, with a bulky basic residue (Lys versus Arg) in position 1, hydrophobic residues (Val versus Ile) in positions 3 and 8, and an acidic residue (Glu versus Asp) in position 4. Therefore, the MHC-M57727–734 complex could potentially interact with the same TCR that recognizes MHC-L2062–2069 through molecular mimicry (62, 63), and the data in Fig. 5 show a high concordance with TCR Vβ usage, consistent with that idea.

Other studies on heterologous immunity have shown that when T cell cross-reactivity between two pathogens occurs, it may depend on the order of the infection sequence and that it does not necessarily occur in all individuals, due to the private specificity of their TCR repertoires (22, 23, 64). This was dramatically illustrated in this study where the cross-reactivity was detected only in the MCMV+LCMV sequence (not LCMV+MCMV), and when it did occur, it was observed approximately in only one of every five MCMV-immune mice. Experiments suggested that M57727–734 is a subdominant epitope of MCMV, but when the M57727–734-specific T cells were stimulated in the context of LCMV infection, they greatly increased in number and dominated the persistent MCMV-specific memory T cell pool. At the same time, the response to subdominant LCMV epitope L2062–2069 became the major LCMV-specific CD8 T cell response. This alteration of the immunodominance hierarchy is another example of how sequential infections can alter T cell responses (19). Further, very high frequencies of CMV-specific T cells can be found in some humans (65), and it is possible that these high frequencies could be driven by cross-reactivity with another pathogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and viruses.

C57BL/6 male mice 5 to 6 weeks of age were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice received the first inoculum when they reached 6 to 7 weeks of age.

LCMV, Armstrong strain, was propagated in baby hamster kidney BHK21 cells (66). MCMV, Smith strain, was passaged in BALB/c mouse salivary glands (45, 67). Supernatants from uninfected baby hamster kidney (BHK) cell cultures and salivary gland homogenates from uninfected naive mice (naive salivary gland [nsg]) were used as sham controls in some experiments. Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 5 × 104 PFU of LCMV or 5 × 105 PFU of MCMV and were considered immune 6 weeks postinfection. Experiments were done in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the ethical care and use of animals in biomedical research according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS).

Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS).

Spleen leukocytes were stimulated on 96-well U-bottomed plates with 1 μg/ml (1 μM) synthetic peptide, 10 U/ml human recombinant interleukin-2 (IL-2; BD Biosciences) and 1 μl/ml of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences) for 5 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 as described previously (19). Anti-CD3ε (250 ng/ml; clone 145-2C11) was used in place of peptides as a positive control. After cells were washed in staining buffer (1% fetal calf serum [FCS] in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) and blocked against nonspecific binding with anti-CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2; Fc block), they were stained with anti-CD4 (clone RM4-5), anti-CD8α (clone 53-6.7), and anti-CD44 (clone IM7) for 20 min at 4°C. Cells were then fixed and permeabilized with Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD Biosciences) for 20 min at 4°C, washed twice with 1× Perm/Wash buffer, and stained with anti-IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2) for 25 min at 4°C. Resuspended samples were analyzed on an LSRII instrument within 5 days.

Tetramer staining.

As previously described (68, 69), biotinylated murine MHC class I (H-2Kb and H-2Db) heavy chain and human β2-microglobulin were separately expressed as inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli and were folded in vitro in the presence of excess peptide. These folded monomers were purified by fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) and made into tetramers by stepwise addition of fluorochrome-conjugated streptavidin. Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated IAb GP66–77 tetramer was provided by the NIH tetramer core facility. Splenocytes were incubated with purified anti-CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2; Fc block) for 10 min at 4°C, washed once with staining buffer, and then stained with tetramers at the appropriate concentrations for 40 min at room temperature in the dark before surface stains were added in a minimal volume for an additional 20 min. Cells were washed twice before fixation with Cytofix (BD Biosciences) for 5 min. Cells were then washed and resuspended for analysis on an LSRII instrument.

DNA extraction and quantitative PCR (qPCR) of MCMV.

Organs collected in dry 1.5-ml vials were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. A fraction of the snap-frozen organ was minced by glass beads in 10 mM Tris–25 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) buffer and incubated with proteinase K (Sigma) and 0.3% sodium dodecyl sulfate (Sigma) overnight in a 60°C water bath. After phenol extraction, the aqueous phase was treated with 10 to 15 U of RNase (Promega) in a 37°C water bath for 1 to 1.5 h. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform in phase lock gel light tubes, precipitated by the addition of 100% ethanol and 3 M sodium acetate, and rinsed with 75% ethanol. Pelleted DNA was air dried at room temperature before being solvated in distilled water and stored at −20°C.

In a total volume of 25 μl, the PCR mixture contained 125 ng of DNA, 400 nM forward primers, 400 nM reverse primers, and QuantiFast SYBR green PCR master mix (Qiagen). The MCMV glycoprotein B (gB) forward primer sequence was 5′-AGGGCTTGGAGAGGACCTACA-3′, and the reverse primer sequence was 5′-GCCCGTCGGCAGTCTAGTC-3′ (70). The mouse β-actin forward primer sequence was 5′-CGAGGCCCAGAGCAAGAGAG-3′, and the reverse primer sequence was 5′-CGGTTGGCCTTAGGGTTCAG-3′ (71). The PCR was performed on a CFX96 system (Bio-Rad) with an initial incubation at 95°C for 10 min to activate the Taq enzyme, followed by 35 amplification cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10s and annealing and extension at 60°C for 30s. A melting curve was generated from 65°C to 95°C with an increment of 0.5°C every 5 s. Serial dilutions of plasmid containing the gB sequence (109 to 102 copies) were included to generate a standard curve. The β-actin standards contained 375 to 0.17 ng of genomic DNA. MCMV copy number was calculated by the CFX System (Bio-Rad) in duplicates and normalized with the amount of genomic DNA (in micrograms).

Assessment of pathology in adipose tissue.

The extent of necrosis in the proximal fat pads in the lower abdomen was visually evaluated on a scale of 0 to 7 as previously described (6): 1 to 2 indicates mild disease with only a few spots on the lower abdominal fat pad, 3 to 4 indicates moderate disease with larger white patches extending out to the upper quadrant of the fat pad, 5 to 6 indicates more severe disease with infiltration of inflammatory cells throughout the fat pad, and 7 indicates that the organs are sticking together.

Statistical analysis.

Student's t test was calculated using Excel or Prism software. Data are presented as the means and standard errors of the means (SEM).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rabinarayan Mishra and Zu Ting Shen for scientific discussions and Laurie Kenney for technical assistance.

This work was funded by U.S. National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 AI007349 and NIH research grants AI017672, AI046629, AI081675, and AI109858.

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schulman JL, Kilbourne ED. 1965. Induction of partial specific heterotypic immunity in mice by a single infection with influenza A virus. J Bacteriol 89:170–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halstead SB. 1988. Pathogenesis of dengue: challenges to molecular biology. Science 239:476–481. doi: 10.1126/science.3277268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kliks SC, Nisalak A, Brandt WE, Wahl L, Burke DS. 1989. Antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus growth in human monocytes as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg 40:444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welsh RM, Che JW, Brehm MA, Selin LK. 2010. Heterologous immunity between viruses. Immunol Rev 235:244–266. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00897.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen HD, Fraire AE, Joris I, Brehm MA, Welsh RM, Selin LK. 2001. Memory CD8+ T cells in heterologous antiviral immunity and immunopathology in the lung. Nat Immunol 2:1067–1076. doi: 10.1038/ni727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selin LK, Varga SM, Wong IC, Welsh RM. 1998. Protective heterologous antiviral immunity and enhanced immunopathogenesis mediated by memory T cell populations. J Exp Med 188:1705–1715. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berg RE, Crossley E, Murray S, Forman J. 2003. Memory CD8+ T cells provide innate immune protection against Listeria monocytogenes in the absence of cognate antigen. J Exp Med 198:1583–1593. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freeman BE, Hammarlund E, Raué H-P, Slifka MK. 2012. Regulation of innate CD8+ T-cell activation mediated by cytokines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:9971–9976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203543109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Homann D, Teyton L, Oldstone MBA. 2001. Differential regulation of antiviral T-cell immunity results in stable CD8+ but declining CD4+ T-cell memory. Nat Med 7:913–919. doi: 10.1038/90950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selin LK, Vergilis K, Welsh RM, Nahill SR. 1996. Reduction of otherwise remarkably stable virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte memory by heterologous viral infections. J Exp Med 183:2489–2499. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.6.2489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau LL, Jamieson BD, Somasundaram T, Ahmed R. 1994. Cytotoxic T-cell memory without antigen. Nature 369:648–652. doi: 10.1038/369648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmerman C, Brduscha-Riem K, Blaser C, Zinkernagel RM, Pircher H. 1996. Visualization, characterization, and turnover of CD8+ memory T cells in virus-infected hosts. J Exp Med 183:1367–1375. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selin LK, Lin M-Y, Kraemer KA, Pardoll DM, Schneck JP, Varga SM, Santolucito PA, Pinto AK, Welsh RM. 1999. Attrition of T cell memory: selective loss of LCMV epitope-specific memory CD8 T cells following infections with heterologous viruses. Immunity 11:733–742. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu H, Andreansky S, Diaz G, Turner SJ, Wodarz D, Doherty PC. 2003. Quantitative analysis of long-term virus-specific CD8+-T-cell memory in mice challenged with unrelated pathogens. J Virol 77:7756–7763. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.14.7756-7763.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S-K, Welsh RM. 2004. Comprehensive early and lasting loss of memory CD8 T cells and functional memory during acute and persistent viral infections. J Immunol 172:3139–3150. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNally JM, Zarozinski CC, Lin M-Y, Brehm MA, Chen HD, Welsh RM. 2001. Attrition of bystander CD8 T cells during virus-induced T-cell and interferon responses. J Virol 75:5965–5976. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.5965-5976.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang J, Lau LL, Shen H. 2003. Selective depletion of nonspecific T cells during the early stage of immune responses to infection. J Immunol 171:4352–4358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang J, Gross D, Nogusa S, Elbaum P, Murasko DM. 2005. Depletion of T cells by type I interferon: differences between young and aged mice. J Immunol 175:1820–1826. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brehm MA, Pinto AK, Daniels KA, Schneck JP, Welsh RM, Selin LK. 2002. T cell immunodominance and maintenance of memory regulated by unexpectedly cross-reactive pathogens. Nat Immunol 3:627–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornberg M, Clute SC, Watkin LB, Saccoccio FM, Kim S-K, Naumov YN, Brehm MA, Aslan N, Welsh RM, Selin LK. 2010. CD8 T cell cross-reactivity networks mediate heterologous immunity in human EBV and murine vaccinia virus infections. J Immunol 184:2825–2838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wlodarczyk MF, Kraft AR, Chen HD, Kenney LL, Selin LK. 2013. Anti-IFN- and peptide-tolerization therapies inhibit acute lung injury induced by cross-reactive influenza A-specific memory T cells. J Immunol 190:2736–2746. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim S-K, Cornberg M, Wang XZ, Chen HD, Selin LK, Welsh RM. 2005. Private specificities of CD8 T cell responses control patterns of heterologous immunity. J Exp Med 201:523–533. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cornberg M, Chen AT, Wilkinson LA, Brehm MA, Kim S-K, Calcagno C, Ghersi D, Puzone R, Celada F, Welsh RM, Selin LK. 2006. Narrowed TCR repertoire and viral escape as a consequence of heterologous immunity. J Clin Invest 116:1443–1456. doi: 10.1172/JCI27804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh RM. 2006. Private specificities of heterologous immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 18:331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin MY, Welsh RM. 1998. Stability and diversity of T cell receptor repertoire usage during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection of mice. J Exp Med 188:1993–2005. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karrer U, Sierro S, Wagner M, Oxenius A, Hengel H, Koszinowski UH, Phillips RE, Klenerman P. 2003. Memory inflation: continuous accumulation of antiviral CD8+ T cells over time. J Immunol 170:2022–2029. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sierro S, Rothkopf R, Klenerman P. 2005. Evolution of diverse antiviral CD8+ T cell populations after murine cytomegalovirus infection. Eur J Immunol 35:1113–1123. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munks MW, Cho KS, Pinto AK, Sierro S, Klenerman P, Hill AB. 2006. Four distinct patterns of memory CD8 T cell responses to chronic murine cytomegalovirus infection. J Immunol 177:450–458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan N, Shariff N, Cobbold M, Bruton R, Ainsworth JA, Sinclair AJ, Nayak L, Moss PAH. 2002. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity drives the CD8 T cell repertoire toward greater clonality in healthy elderly individuals. J Immunol 169:1984–1992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan N, Hislop A, Gudgeon N, Cobbold M, Khanna R, Nayak L, Rickinson AB, Moss PAH. 2004. Herpesvirus-specific CD8 T cell immunity in old age: cytomegalovirus impairs the response to a coresident EBV infection. J Immunol 173:7481–7489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cicin-Sain L, Sylwester AW, Hagen SI, Siess DC, Currier N, Legasse AW, Fischer MB, Koudelka CW, Axthelm MK, Nikolich-Zugich J, Picker LJ. 2011. Cytomegalovirus-specific T cell immunity is maintained in immunosenescent rhesus macaques. J Immunol 187:1722–1732. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bahl K, Kim S-K, Calcagno C, Ghersi D, Puzone R, Celada F, Selin LK, Welsh RM. 2006. IFN-induced attrition of CD8 T cells in the presence or absence of cognate antigen during the early stages of viral infections. J Immunol 176:4284–4295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider K, Loewendorf A, De Trez C, Fulton J, Rhode A, Shumway H, Ha S, Patterson G, Pfeffer K, Nedospasov SA, Ware CF, Benedict CA. 2008. Lymphotoxin-mediated crosstalk between B cells and splenic stroma promotes the initial type I interferon response to cytomegalovirus. Cell Host Microbe 3:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazo IB, Honczarenko M, Leung H, Cavanagh LL, Bonasio R, Weninger W, Engelke K, Xia L, McEver RP, Koni PA, Silberstein LE, Andrian von UH. 2005. Bone marrow is a major reservoir and site of recruitment for central memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity 22:259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tokoyoda K, Zehentmeier S, Hegazy AN, Albrecht I, Grün JR, Löhning M, Radbruch A. 2009. Professional memory CD4+ T lymphocytes preferentially reside and rest in the bone marrow. Immunity 30:721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wherry EJ. 2011. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol 12:492–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yi JS, Cox MA, Zajac AJ. 2010. T-cell exhaustion: characteristics, causes and conversion. Immunology 129:474–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Snyder CM, Cho KS, Bonnett EL, van Dommelen S, Shellam GR, Hill AB. 2008. Memory inflation during chronic viral infection is maintained by continuous production of short-lived, functional T cells. Immunity 29:650–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torti N, Walton SM, Brocker T, Rülicke T, Oxenius A. 2011. Non-hematopoietic cells in lymph nodes drive memory CD8 T cell inflation during murine cytomegalovirus infection. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002313. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seckert CK, Grießl M, Büttner JK, Scheller S, Simon CO, Kropp KA, Renzaho A, Kühnapfel B, Grzimek NKA, Reddehase MJ. 2012. Viral latency drives “memory inflation”: a unifying hypothesis linking two hallmarks of cytomegalovirus infection. Med Microbiol Immunol 201:551–566. doi: 10.1007/s00430-012-0273-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoddart CA, Cardin RD, Boname JM, Manning WC, Abenes GB, Mocarski ES. 1994. Peripheral blood mononuclear phagocytes mediate dissemination of murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol 68:6243–6253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddehase MJ, Balthesen M, Rapp M, Jonjiæ S, Paviæ I, Koszinowski UH. 1994. The conditions of primary infection define the load of latent viral genome in organs and the risk of recurrent cytomegalovirus disease. J Exp Med 179:185–193. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koffron AJ, Hummel M, Patterson BK, Yan S, Kaufman DB, Fryer JP, Stuart FP, Abecassis MI. 1998. Cellular localization of latent murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol 72:95–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seckert CK, Renzaho A, Tervo H-M, Krause C, Deegen P, Kühnapfel B, Reddehase MJ, Grzimek NKA. 2009. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are a site of murine cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation. J Virol 83:8869–8884. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00870-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bukowski JF, Woda BA, Welsh RM. 1984. Pathogenesis of murine cytomegalovirus infection in natural killer cell-depleted mice. J Virol 52:119–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pawelec G, Larbi A, Derhovanessian E. 2010. Senescence of the human immune system. J Comp Pathol 142(Suppl 1):S39–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.jcpa.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Connor L, Blackman MA, Woodland DL. 2012. Limiting diversity of the CD8+ T cell repertoire and T cell clonal expansions: the repercussions of age on immunity. Open Longev Sci 6:39–46. doi: 10.2174/1876326X01206010039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. 2013. Understanding immunosenescence to improve responses to vaccines. Nat Immunol 14:428–436. doi: 10.1038/ni.2588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munks MW, Gold MC, Zajac AL, Doom CM, Morello CS, Spector DH, Hill AB. 2006. Genome-wide analysis reveals a highly diverse CD8 T cell response to murine cytomegalovirus. J Immunol 176:3760–3766. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kotturi MF, Peters B, Buendia-Laysa F, Sidney J, Oseroff C, Botten J, Grey H, Buchmeier MJ, Sette A. 2007. The CD8+ T-cell response to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus involves the L antigen: uncovering new tricks for an old virus. J Virol 81:4928–4940. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02632-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmidt NW, Harty JT. 2011. Cutting edge: attrition of plasmodium-specific memory CD8 T cells results in decreased protection that is rescued by booster immunization. J Immunol 186:3836–3840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang HY, Joris I, Majno G, Welsh RM. 1985. Necrosis of adipose tissue induced by sequential infections with unrelated viruses. Am J Pathol 120:173–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nie S, Lin S-J, Kim S-K, Welsh RM, Selin LK. 2010. Pathological features of heterologous immunity are regulated by the private specificities of the immune repertoire. Am J Pathol 176:2107–2112. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Agarwal S, Busse PJ. 2010. Innate and adaptive immunosenescence. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 104:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mekker A, Tchang VS, Haeberli L, Oxenius A, Trkola A, Karrer U. 2012. Immune senescence: relative contributions of age and cytomegalovirus infection. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002850. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bubiæ I, Wagner M, Krmpotic A, Saulig T, Kim S, Yokoyama WM, Jonjiæ S, Koszinowski UH. 2004. Gain of virulence caused by loss of a gene in murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol 78:7536–7544. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7536-7544.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koch S, Larbi A, Ozcelik D, Solana R, Gouttefangeas C, Attig S, Wikby A, Strindhall J, Franceschi C, Pawelec G. 2007. Cytomegalovirus infection: a driving force in human T cell immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1114:23–35. doi: 10.1196/annals.1396.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E, Larbi A, Strindhall J, Wikby A. 2009. Cytomegalovirus and human immunosenescence. Rev Med Virol 19:47–56. doi: 10.1002/rmv.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moss P. 2010. The emerging role of cytomegalovirus in driving immune senescence: a novel therapeutic opportunity for improving health in the elderly. Curr Opin Immunol 22:529–534. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuparinen T, Marttila S, Jylhävä J, Tserel L, Peterson P, Jylhä M, Hervonen A, Hurme M. 2013. Cytomegalovirus (CMV)-dependent and -independent changes in the aging of the human immune system: a transcriptomic analysis. Exp Gerontol 48:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Furman D, Jojic V, Sharma S, Shen-Orr SS, Angel CJL, Onengut-Gumuscu S, Kidd BA, Maecker HT, Concannon P, Dekker CL, Thomas PG, Davis MM. 2015. Cytomegalovirus infection enhances the immune response to influenza. Sci Transl Med 7:281ra43. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hagerty DT, Allen PM. 1995. Intramolecular mimicry. Identification and analysis of two cross-reactive T cell epitopes within a single protein. J Immunol 155:2993–3001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Welsh RM, Selin LK. 2002. No one is naive: the significance of heterologous T-cell immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2:417–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Che JW, Selin LK, Welsh RM. 2015. Evaluation of non-reciprocal heterologous immunity between unrelated viruses. Virology 482:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gillespie GM, Wills MR, Appay V, O'Callaghan C, Murphy M, Smith N, Sissons P, Rowland-Jones S, Bell JI, Moss PA. 2000. Functional heterogeneity and high frequencies of cytomegalovirus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes in healthy seropositive donors. J Virol 74:8140–8150. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.17.8140-8150.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Welsh RM, Lampert PW, Burner PA, Oldstone MBA. 1976. Antibody-complement interactions with purified lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virology 73:59–71. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90060-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Selgrade MK, Daniels MJ, Hu PC, Miller FJ, Graham JA. 1982. Effects of immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide on acute murine cytomegalovirus infection and virus-augmented natural killer cell activity. Infect Immun 38:1046–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shen ZT, Brehm MA, Daniels KA, Sigalov AB, Selin LK, Welsh RM, Stern LJ. 2010. Bi-specific MHC heterodimers for characterization of cross-reactive T cells. J Biol Chem 285:33144–33153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.141051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brehm MA, Markees TG, Daniels KA, Greiner DL, Rossini AA, Welsh RM. 2003. Direct visualization of cross-reactive effector and memory allo-specific CD8 T cells generated in response to viral infections. J Immunol 170:4077–4086. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vliegen I, Herngreen S, Grauls G, Bruggeman C, Stassen F. 2003. Improved detection and quantification of mouse cytomegalovirus by real-time PCR. Virus Res 98:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mishra R, Chen AT, Welsh RM, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E. 2010. NK cells and γδ T cells mediate resistance to polyomavirus-induced tumors. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000924. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]