ABSTRACT

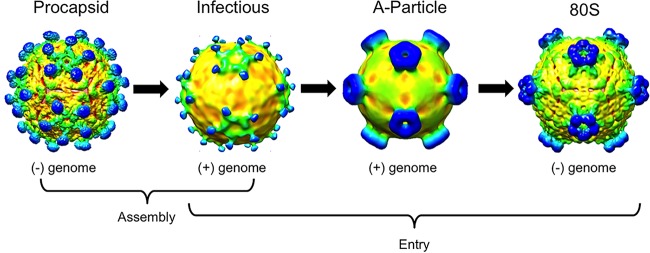

The picornavirus-like deformed wing virus (DWV) has been directly linked to colony collapse; however, little is known about the mechanisms of host attachment or entry for DWV or its molecular and structural details. Here we report the three-dimensional (3-D) structures of DWV capsids isolated from infected honey bees, including the immature procapsid, the genome-filled virion, the putative entry intermediate (A-particle), and the empty capsid that remains after genome release. The capsids are decorated by large spikes around the 5-fold vertices. The 5-fold spikes had an open flower-like conformation for the procapsid and genome-filled capsids, whereas the putative A-particle and empty capsids that had released the genome had a closed tube-like spike conformation. Between the two conformations, the spikes undergo a significant hinge-like movement that we predicted using a Robetta model of the structure comprising the spike. We conclude that the spike structures likely serve a function during host entry, changing conformation to release the genome, and that the genome may escape from a 5-fold vertex to initiate infection. Finally, the structures illustrate that, similarly to picornaviruses, DWV forms alternate particle conformations implicated in assembly, host attachment, and RNA release.

IMPORTANCE Honey bees are critical for global agriculture, but dramatic losses of entire hives have been reported in numerous countries since 2006. Deformed wing virus (DWV) and infestation with the ectoparasitic mite Varroa destructor have been linked to colony collapse disorder. DWV was purified from infected adult worker bees to pursue biochemical and structural studies that allowed the first glimpse into the conformational changes that may be required during transmission and genome release for DWV.

KEYWORDS: 80S, DWV, conformation change, deformed wing virus, 5-fold spikes, honey bee, insect, life cycle, picornavirus, procapsid

INTRODUCTION

The European honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) is a major agricultural resource critical for the pollination of many important food crops (1, 2). There are concerns about the decline in populations of managed honey bees observed since 2006 (3). Often, this decrease in honey bee numbers is attributed to infection with several species of viruses (4) and the wide-spread ectoparasitic mite Varroa destructor (5), which can double as a viral vector. Multiple studies have shown that deformed wing virus (DWV), particularly when associated with high levels of V. destructor infestation, is linked to overwintering losses of colonies and “colony collapse disorder,” where the number of adults bees in a particular hive plummets dramatically as a consequence of unexplained factors (3, 6–9). Transmission of DWV to honeybees can occur horizontally, via consumption of contaminated pollen, and through direct contact between adult bees (8, 10–13). The virus can also be transmitted vertically if an infected drone inseminates a queen and by a DWV-positive queen laying infected eggs (13, 14). Infection with DWV during pupation leads to the hallmark appearance of incompletely developed and crumpled wings, which is lethal, as bees do not live long after emergence from the pupal stage or are directly removed from the hive by other bees (15, 16) (M. C. Pizzorno, personal observation).

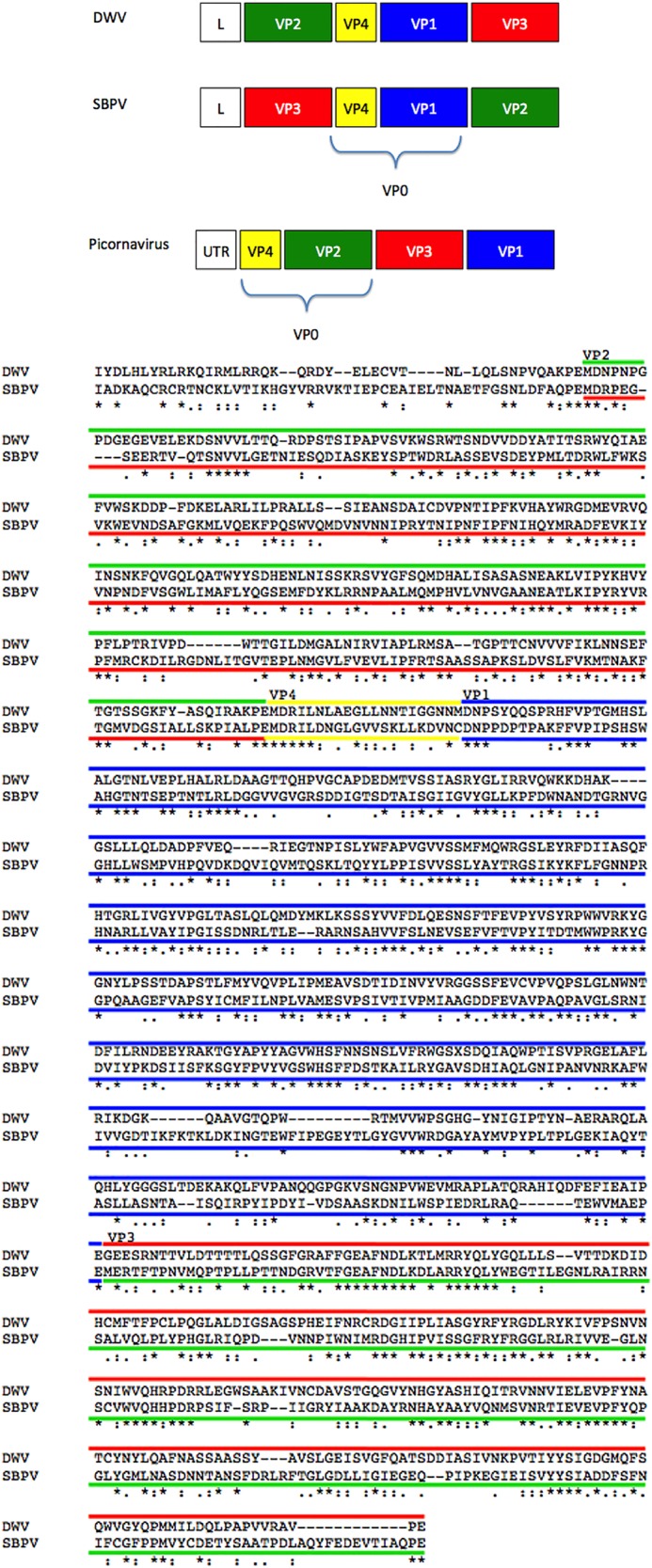

Within the Picornavirales order, DWV belongs to the family Iflaviridae (International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses [ICVT], 9th report). The DWV genome consists of positive-strand RNA organized similarly to RNA of the mammalian picornaviruses (17), with a 5′ untranslated region that likely functions as an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (18) and a single open reading frame (ORF) encoding a 2,893-amino-acid polyprotein, with the structural proteins at the N terminus and the nonstructural proteins at the C terminus (17). Structural proteins are released by cleavage and form a protomer unit comprised of VP1, VP0, and VP3 (17). During picornavirus assembly, 5 copies of the virus protomer form pentameric structures and 12 of these building blocks incorporate a progeny genome to assemble the infectious virion. Many picornaviruses also form an empty capsid of 12 self-assembled pentamers, sometimes called a procapsid, which contains uncleaved VP0. When genomic RNA associates with pentamers, often, VP0 is cleaved to produce VP4 and VP2; however, this cleavage has not yet been established for DWV.

The capsid of DWV is a 30-nm-diameter nonenveloped icosahedron composed of structural proteins VP0 (VP4 plus VP2), VP1, and VP3 (17). The VP1 protein of DWV is the largest (44-kDa) capsid protein of any virus in the Picornavirales order, and sequence alignment indicates a 171-residue C-terminal extension relative to other picornaviruses (17). Structural proteins VP2 and VP3 (32 kDa and 28 kDa, respectively) are more similar in size to other picornavirus capsid proteins. A significant difference between the capsid polyproteins of insect picornaviruses is the location of the VP4 protein, which is located internally and immediately downstream of VP2 rather than at the N terminus as in picornaviruses (17, 19). Due to this location, the VP4 protein is not myristylated in the insect viruses. During picornavirus entry, capsids undergo a conformational change after binding to the entry receptor that includes the release of some VP4 molecules that form a pore in the host membrane for translocation of the RNA genome. DWV VP4 may function by being inserted directly into cellular membranes during viral entry (20).

Many insect viruses share a structural feature called “strand swapping,” which refers to the N terminus of the VP2 protein connecting two protomers by bridging the icosahedral 2-fold. The related Triatoma virus (TrV) also displays a structural feature called a “crown” that is comprised of the VP1 N termini forming spike-like extensions surrounding the 5-fold vertices. These crowns have also been found in Ljungan virus, a related picornavirus (21), and in the insect virus structure that was recently solved for another member of the Iflaviridae family, slow bee paralysis virus (SBPV) (22).

Very little is known about DWV host attachment, entry, and genome release. Based on sequence alignment, the most closely related viruses are Ljungan virus, TrV, and hepatitis A virus (HAV). TrV has several picornavirus-like features, including the production of a procapsid, a naturally occurring empty capsid made during assembly (23). The infectious picornavirus undergoes a conformational change during host entry, forming an altered entry intermediate or A-particle. After release of the genome, an empty capsid remains that sediments at a different buoyant density (80S) than the other forms of the capsid. These picornavirus entry steps can be mimicked in the laboratory setting by heating infectious particles to produce A-particle and 80S. Heating TrV virus particles has also been shown to release the genome, resulting in a stable empty capsid (24).

Here we report the first high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the honey bee virus, DWV, isolated from infected honey bees. The honey bee DWV lysate was infectious, and both RNA-filled and empty capsids were visualized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Upon purification, two structurally distinct empty capsid forms were isolated. Although comprised of the same capsid proteins, the capsids have unique buoyant densities and capsid topologies. The cryo-EM density maps show that DWV capsids have “strand swapping” of the VP2 protein that crosses from one asymmetric unit to the next. Spikes composed of the extended VP1 C terminus decorate the 5-fold vertices; however, these spikes exist in two distinct conformations that we describe as open and closed. Further analysis identified the conformation of the genome-filled capsid and a putative A-particle, suggesting a model for host attachment and entry of DWV. Based on this first structural characterization of an important agricultural pathogen, we propose that DWV shares features with picornaviruses, including the assembly of a procapsid and the formation of an 80S-like empty capsid after genome release that is accompanied by large conformational movements of the VP1 C-terminal spikes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Detection of DWV.

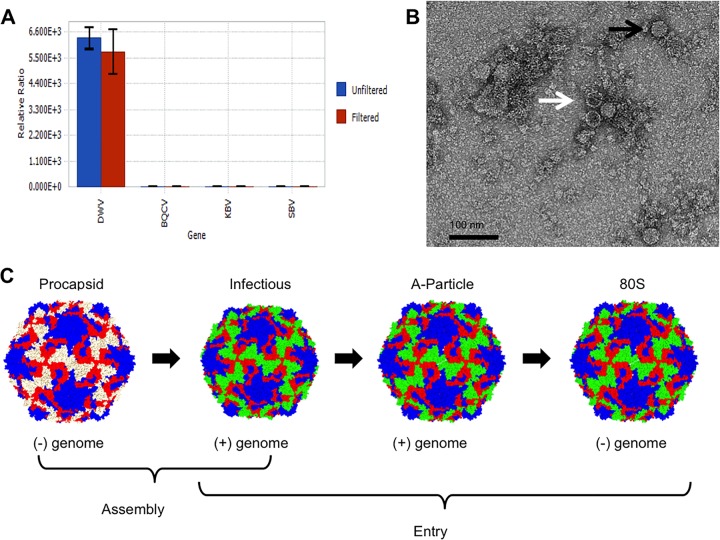

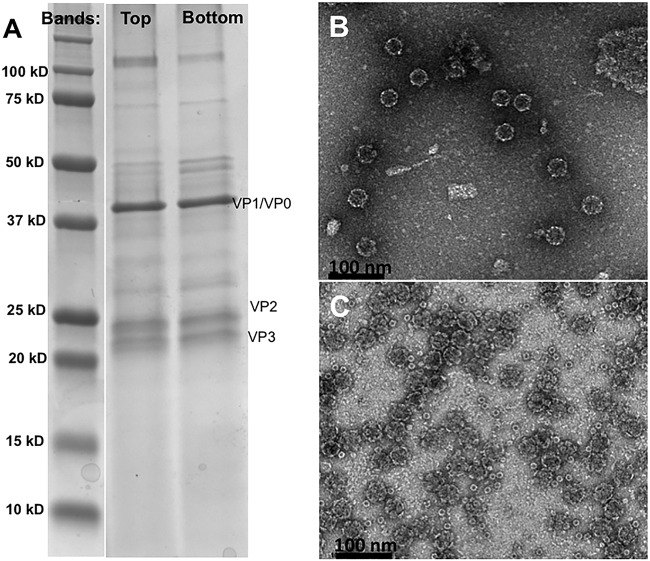

Homogenates made from adult worker honey bees with obvious deformed wings were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) using primers for DWV and other honey bee viruses. The only virus detected in samples was DWV (Fig. 1A). When these infectious bee homogenates were examined by negative-stain transmission electron microscopy (TEM), both RNA-filled and empty virus capsids were seen (Fig. 1B). Since RNA-filled capsids and procapsids are often found in lysates from picornaviruses (21, 25, 26), this finding suggests that DWV makes a procapsid along with the RNA-packaged infectious virus (Fig. 1C). After differential centrifugation of the homogenate, two protein bands were observed, as has been seen previously for large-volume picornavirus preparations where the top band corresponds to the procapsid and the lower band to the genome-packaged infectious virion (27). However, after the bands were collected and incubated overnight at 4°C and the buffer was exchanged for examination by negative-stain TEM (Fig. 2B and C), both bands were found to contain ∼30-nm-diameter empty capsids. Thus, upon further handling of the two virus capsid types, the RNA-packaged virus lost the genome, resulting in an empty capsid. At this point, we could not definitively distinguish between preexisting procapsids and newly formed 80S-like empty capsids (28). SDS-PAGE analysis of the bands confirmed the presence of virus proteins but also did not allow differentiation between the procapsid and the 80S particle (Fig. 2A).

FIG 1.

Detection of DWV in honey bee lysate. (A) Quantitative real-time PCR of DWV-infected honey bee homogenates. Unfiltered and filtered honey bee extracts were subjected to qRT-PCR using primers corresponding to four different common honey bee viruses, including DWV, black queen cell virus (BQCV), Kashmir bee virus (KBV), and sacbrood virus (SBV). The ratio of RNA of each virus to an internal control gene is shown. DWV was the only virus detected, and the amount of virus detected was unaffected by the filtration process. (B) Visualization of DWV capsids. Negatively stained TEM of DWV-infected bee homogenate shows a mixture of full capsids (black arrow) and empty capsids (white arrow). (C) A schematic showing that for picornaviruses, two types of capsids, procapsid and genome-filled virus capsid, are assembled. During host attachment and entry, an entry intermediate, the A-particle, is formed and is then triggered to release genome, leaving an empty capsid, referred to as an 80S capsid.

FIG 2.

(A) SDS-PAGE staining with Coomassie blue shows that proteins corresponding to VP1 and VP0 (VP1/4), VP2, and VP3 can be detected in the top and lower bands. A protein standard (lane 1) is used as a sizing ladder. (B and C) Material from each of the two bands that formed during sucrose gradient purification were negatively stained and imaged by TEM. The top (B) and lower (C) bands both contain empty capsids.

The top and lower bands contain empty virus capsids with different structures.

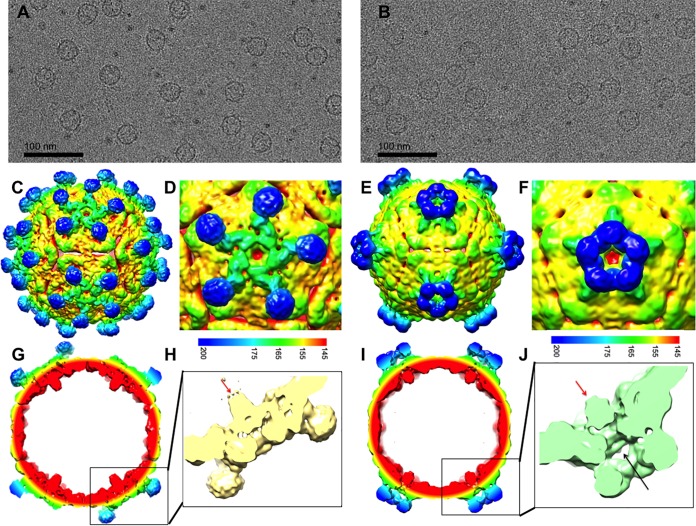

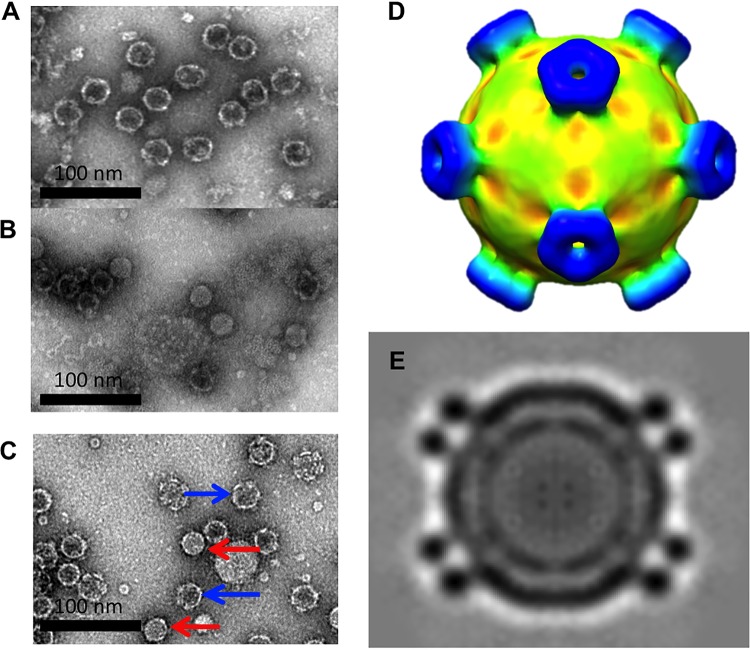

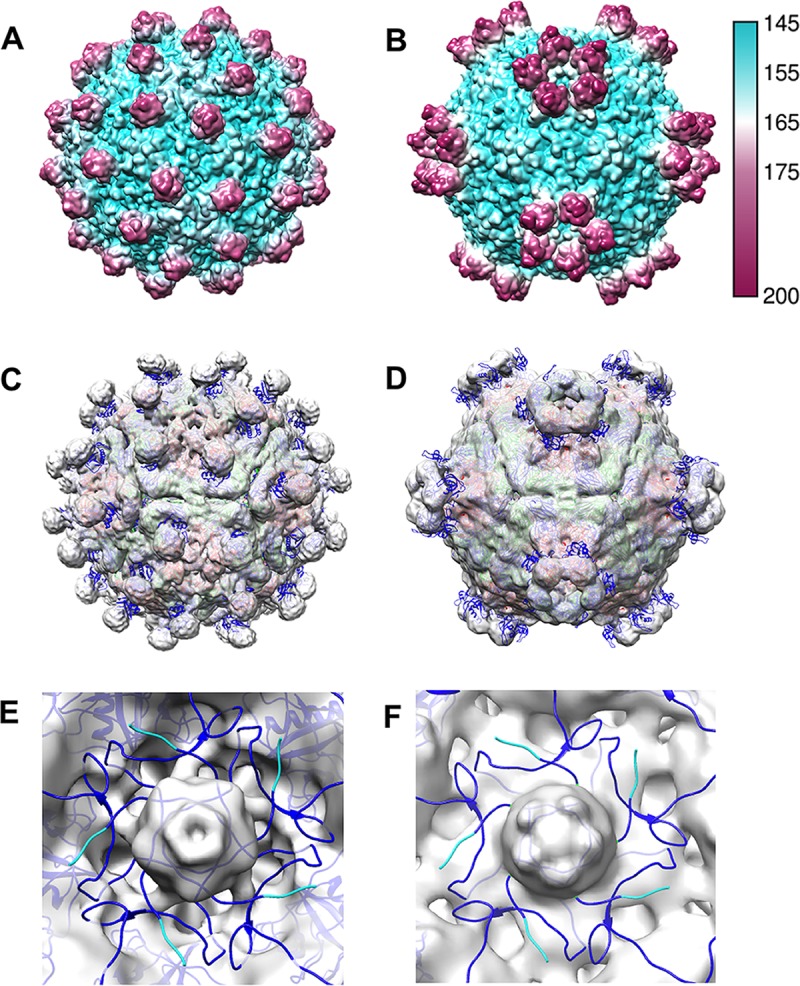

Samples from top and bottom bands were vitrified for cryo-EM data collection and icosahedral image reconstruction (Fig. 3 and Table 1). The 3-D reconstruction of the top band, DWV1, showed capsids with pentameric units joined by minimal contacts at the icosahedral 3-fold axes and more substantial connections at the 2-fold axes. The spikes of density on the external capsid surface around but at some distance from each icosahedral 5-fold vertex and arranged in an open conformation were striking features (Fig. 3C and D; blue spikes). The 5-fold vertex is closed by a strong density plug at the inner capsid surface that has multiple thick connections to the capsid shell (Fig. 3G and H).

FIG 3.

Cryo-EM reconstructions of two different types of empty DWV capsids. (A and B) Micrographs of (A) DWV1 and (B) DWV2 show empty capsids. (C to J) The DWV1 (C, D, G, and H) (6.1-Å) and DWV2 (E, F, I, and J) (7.6-Å) cryo-EM reconstructions are visualized at a contour level of 1σ, surface rendered, and colored radially according to the scale bar. (G to J) Cutaway and closeup views of the virus 5-fold vertices show the different conformations of the density spikes (blue) and the 5-fold density plug (red arrows) that may block access to the capsid interior. (J) Tenuous connections (black arrow) seem to hold a 5-fold density plug (red arrow) at the inner capsid surface, although there is a clear opening through the capsid shell at each 5-fold vertex which is better visualized with a continuous color scheme for DWV1 (yellow) and DVV2 (green) in the zoomed views.

TABLE 1.

Summary of data for 3-D reconstructions

| Capsid type | Microscopea | Method | No. of micrographs | No. of particles | No. of particles used | Defocus range (μm) | Resolution (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DWV1 | Polara 300 | Cryo-EM | 3,357 | 99,938 | 79,958 | 0.74 to 5.58 | 6.09 |

| DWV2 | Polara 300 | Cryo-EM | 2,881 | 18,581 | 13,136 | 0.19 to 5.57 | 7.59 |

| RNA filled | JEM1400 | Negative stain | 101 | 204 | 102 | 0.47 to 4.73 | 23 |

| A-particle | JEM2100 | Cryo-EM | 380 | 1,893 | 1,860 | 0.05 to 5.47 | 18 |

Polara, 300-kV cryo-EM with field emission gun and Falcon II direct electron detector; JEM1400, 160-kV TEM with tungsten filament for negative stain data collection with CCD camera; JEM2100, 200-kV cryo-EM with LaB6 and CCD camera.

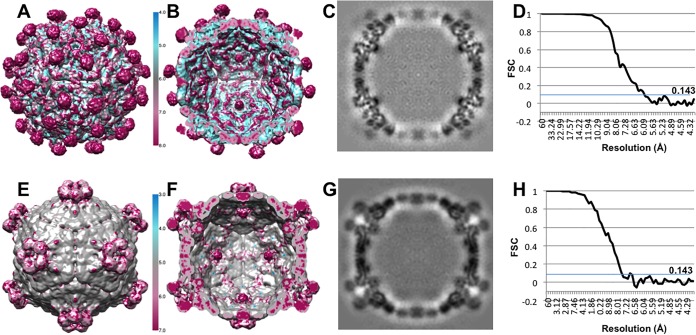

The density map from the lower band, DWV2, was also decorated with spikes at each 5-fold vertex; however, the protrusions were much closer to the axis and formed a closed ring structure (Fig. 3E and F; blue spikes). The interpentamer bridge at the 2-fold axis was present, whereas the connections between pentamers at the 3-fold axis seemed more substantial. There was an open pore through the capsid shell at each 5-fold vertex that, together with the ring structure, forms a tube-like extension (Fig. 3I and J). A plug of density was also present beneath the 5-fold pore but was held in place with only tenuous density connections to the capsid shell (Fig. 3J). The local resolution of the maps shows that the spike density has lower resolution, suggesting flexibility. The density displayed in the central sections attests to the resolutions of 6.1 and 7.6 Å for DWV1 and DWV2, respectively (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Quality and resolution of the DWV cryo-EM reconstructions. DWV1 (A and B) and DWV2 (E and F) are colored according to local-resolution estimations (see scale bars). The capsid shells reach higher resolutions than the flexible 5-fold decorations, with DWV1 spikes at lower resolution than the DWV2 spikes. (C and G) The map central sections (protein is indicated in black) of DWV1 (C) and DWV2 (G) show the quality of the maps. (D and H) Because the data sets were split initially and the halves reconstructed separately, the resolution for each reconstruction was assessed using the gold standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) cutoff value of 0.143, yielding 6.1-Å and 7.6-Å resolutions for DWV1 (D) and DWV2 (H), respectively.

Capsid composition.

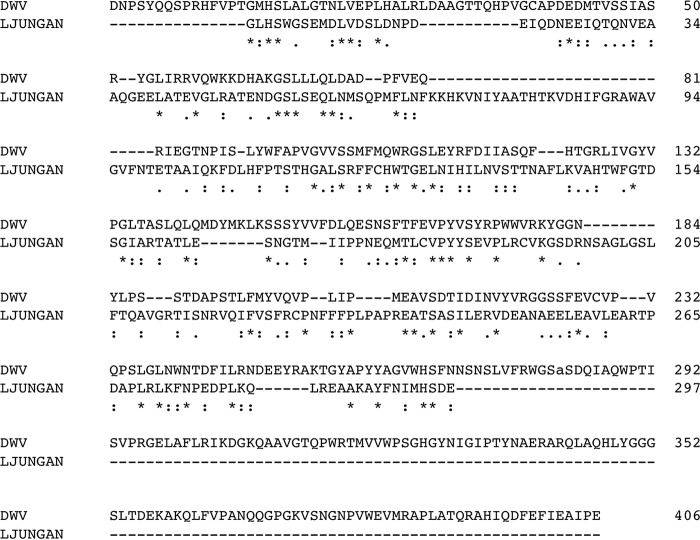

DWV has a VP1 C terminus that is significantly longer that those of related viruses and is 171 residues longer than that of the related Ljungan virus, which has 49% sequence similarity based on alignment of the regions encoding the structural proteins (see Materials and Methods and Fig. 5). The Ljungan virus capsid structure (PDB ID 3JB4) was fitted into the DWV1 (Fig. 6) and DWV2 (21) cryo-EM maps. The last C-terminal residue of Ljungan VP1 mapped to the base of the DWV spike, leaving most of the spike density unfilled (1.22 × 105 Å3 for both DWV1 and DWV2). Apart from the spikes, there was no other DWV density left unfilled from the fitted Ljungan virus structure that might accommodate the DWV VP1 C-terminal extension. The entire DWV VP1 sequence was submitted to the structure prediction server Robetta (http://robetta.bakerlab.org) (29, 30), and the resulting Robetta model was aligned with the Ljungan VP1 structure. The first 221 amino acids of the predicted DWV protein had a structure similar to that of Ljungan VP1. The 171 unique C-terminal residues of DWV model contained two helices (residues 338 to 355 and 358 to 361). The Robetta model was fitted into both DWV1 (Fig. 6B) and DWV2 to predict the movement of the spikes during genome release (see Movie S1 in the supplemental material). The 171 C-terminal spike domain residues of our model appear to rock ∼40° about the hinge at the base, with residues Ser236 to Thr243 appearing to be the pivot point. The large movement of the spikes produces the effect of opening the vertex channel through the capsid shell.

FIG 5.

Alignment of DWV and Ljungan virus VP1 residues shows C-terminal extension of DWV VP1. The two viruses share 49% sequence identity. *, fully conserved residue; :, residues that share similar properties; ., residues that share weakly similar properties.

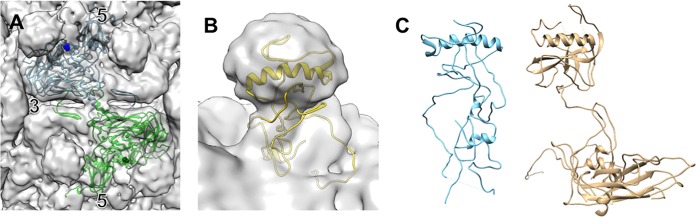

FIG 6.

DWV capsid composition and spike movement. (A) The Ljungan virus structure (PDB ID 3JB4) (blue and green ribbon) fitted into the DWV1 map illustrates that the last C-terminal residue of VP1 maps to the base of the 5-fold spike density (blue sphere). Symmetry axes are indicated, and the strand-swapping mechanism can be seen where VP2 ribbons cross the 2-fold density bridge. (B) The last 171 C-terminal VP1 residues of DWV were predicted to form a helix-loop structure (yellow) that was fitted into the spike density. (C) The predicted model of DWV VP1 C-terminal extension has a structure similar to the VP1 crystal structure of slow bee paralysis virus (PDB ID 5J98) (22).

A defining characteristic of related insect virus capsids is the linking of pentamers by a strand-swapping mechanism that occurs when the N terminus of a VP2 protein extends across the icosahedral 2-fold axis to interact with residues in the neighboring pentamer. This extension creates a density bridge. The pentamer that receives the VP2 N terminus donates a VP2 N terminus back across that same bridge, creating an effective “protein staple” across each 2-fold. Ljungan virus also uses strand swapping to connect pentameric units, as indicated by the fitted Ljungan VP2 that passed through a specific bridge of DWV density located at the 2-fold axis in both DWV maps (Fig. 6A).

Fitting of the Ljungan virus structure aided in interpretation of the DWV capsid composition; however, the structure of a more closely related virus, slow bee paralysis virus (SBPV), was recently solved (22). Although its sequence similarity is lower than that seen with Ljungan virus (33%), the capsid structure of SBPV shares similar characteristics with DWV, including the 5-fold spikes and VP2 strand swapping (Fig. 7). Fitting the SBPV structures (PDB ID 5J98 and 5J96) into DWV1 and DWV2 resulted in relatively poor correlation coefficients (0.35 and 0.59, respectively), likely due to spike and 5-fold-related structures that are out of density (Fig. 7C and D). The fittings did reveal that the N termini of VP1 map to the strong density plugs beneath the 5-fold channel. The VP1 N termini are mostly out of density, wrapping around the 5-fold vertex in an intertwined configuration, much like the placement of VP4 in picornavirus structures. The 5-fold density plug remained unfilled; although the strength of the cryo-EM density (equal to that of the strongest capsid features) suggests it might correspond to RNA or VP4, it cannot yet be interpreted. The exact location of DWV VP4, or even whether it has been cleaved from VP0, remains unknown.

FIG 7.

Comparison of DWV1 and DWV2 to SBPV. (A and B) Two structures of slow bee paralysis virus (PDB ID 5J98 and 5J96) (22) were used to calculate ∼7-Å surface-rendered radially colored (see key) maps to compare gross surface topologies to those of DWV1 and DWV2, respectively. (C and D) The SBPV structures (VP1, -2, and -3 are color coded blue, green, and red according to the gene order presented in Fig. 8) were fitted into the DWV1 and DWV2 cryo-EM maps (transparent gray), and correlation coefficients were obtained that signified a moderately poor fit despite the obvious overall similarities. (E and F) The zoomed view shows the internal surface of DWV1 and DWV2, respectively (gray), at the 5-fold vertex, with SBPV structures fitted to show that the VP1 N termini (blue) surround the 5-fold vertex. If VP0 were not cleaved, the VP4 portion would map to this region, which is similar to the location of VP4 in picornaviruses. The large gray plug of unfilled density was equal in magnitude to the capsid density.

During the DWV and SBPV comparisons, several inconsistencies in nomenclature were found due to the use of different conventions by different researchers. During previous annotations of the DWV and the SBPV genomes, the virus proteins were named according to a molecular weight convention, resulting in a DWV gene order of VP2, -4, -1, and -3 and a SBPV gene order of VP3, -4, -1, and -2 (Fig. 8) (17, 31). However, in the annotations of the recently determined SBPV crystal structure, the virus proteins were labeled according to structural homology with picornaviruses, which resulted in assigning VP1, -2, and -3 as VP3, -1, and -2, respectively. Since SBPV VP1 (46 kDa), -2 (29 kDa), and -3 (27 kDa) had been characterized previously (31), we used the previous assignment here for comparisons to DWV. To provide consistency and clarity, the alignment of DWV with SBPV was color coded (Fig. 8) and the DWV annotation published in 2006 (17) was used throughout.

FIG 8.

The gene order for SBPV, DWV, and picornaviruses is shown with boxes color coded to represent VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4 (blue, green, red, and yellow, respectively). The alignment of the P1 region encoding the structural proteins for DWV and SBPV (33% sequence similarity) has been similarly color coded with lines to indicate viral proteins. For consistency, the DWV published gene order and the picornavirus color code were used throughout this work. *, fully conserved residue; :, residues that share similar properties; ., residues that share weakly similar properties.

DWV1 is the procapsid and DWV2 is an 80S-like empty capsid.

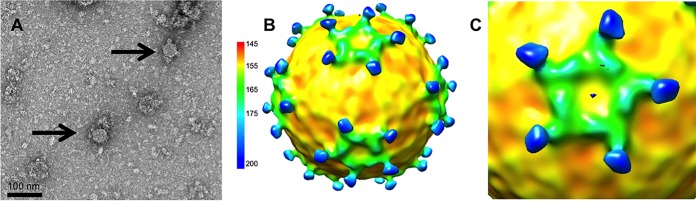

The two different empty capsid forms identified from the top band and lower band are likely a procapsid and an 80S-like particle that resulted from the virion releasing genome upon further handling during the purification. The major structural difference between the two is in the position of the 5-fold spikes, suggesting that the emptied virion has undergone significant conformational changes in order to release the genome. To learn more about the capsid conformational changes of DWV, the preparations of infectious honey bee homogenate were reexamined by negative-stain TEM (Fig. 9A). Approximately 200 RNA-filled virions were selected for reconstruction, and despite the limitation on resolution, the density map clearly revealed 5-fold spikes in the open conformation (Fig. 9B and C) similarly to DWV1. This result suggests that the procapsid (DWV1) and the RNA-containing virus capsid share the same conformation whereas DWV2 is likely an empty 80S-like particle that had undergone a conformational transformation in order to release its RNA.

FIG 9.

The structure of the RNA-filled DWV capsid from infectious bee lysates. (A) Negatively stained micrographs of infected bee homogenate were used to select 102 genome-filled infectious virus capsids for a low resolution (∼25-Å resolution) negative-stain reconstruction to reveal the spike conformation. (B and C) The RNA-filled capsids have spikes in the open conformation, similarly to the DWV1 reconstruction.

RNA-filled virus releases genome upon incubation.

With the aim to stabilize the RNA-filled virus capsids, additional DWV infectious bee homogenate was purified using new purification buffer (pH 7.4). Again, ultracentrifugation resulted in distinct top and lower bands, which were collected, buffer exchanged, and viewed by TEM (Fig. 10A and B). Whereas only empty capsids were seen again in the top band, the lower band was found to contain a mixed population of filled and empty capsids in a ratio of approximately 50:50. The presence of filled and empty capsids suggested that infectious virus might have been releasing RNA. To test this possibility, an aliquot from the lower band was incubated at 37°C overnight and viewed the next day by TEM (Fig. 10C). After the incubation, the population was characterized by slightly filled particles, reminiscent of A-particles (32–34) and empty capsids. The sample was vitrified and a data set collected using the home source cryo-EM (see Materials and Methods), resulting in a cryo-EM map of modest resolution. The density map showed a virus particle with density corresponding to RNA in the interior and the 5-fold spike conformation in the closed ring-like form (Fig. 10D and E).

FIG 10.

Results from the second purification of infectious honey bee lysate. (A and B) Negatively stained TEM images of the (A) top and (B) lower bands. The top band remained empty, as before, whereas the lower band contained approximately 50% genome-filled virus. (C) A negatively stained micrograph of an aliquot from the lower band after incubation at 37°C for 24 h shows different distributions, as most of the filled capsids had lost the genome (blue arrows). The filled viruses that retain the genome appear to have less dense centers than those previous observed (red arrows), consistent with the presence of A-particles. The low-resolution (18-Å) cryo-EM reconstruction (D) and central section (E) of putative A-particle (C) reveal that the spikes had undergone a conformational change into the closed tube-like form after incubation.

Model for necessary conformational changes of DWV.

Bee homogenate is infectious (35–37), and we could detect DWV virions with packaged RNA prior to purification by ultracentrifugation. Currently, it is unknown which step in the purification process triggers infectious DWV to change from the open to the closed conformation that accompanies genome release. Similar conversion of full picornavirus to other intermediate forms of capsid during purification has been seen before (38). Heat, receptor interactions, and pH changes can trigger picornavirus genome release, providing several parameters for modification of the DWV purification protocol.

Ultracentrifugation reproducibly resulted in two distinct bands. Gel electrophoresis analysis demonstrated that VP1 (or VP0), VP2, and VP3 were present in all four bands. As yet, it is not known whether the VP0 protein of DWV cleaves into VP4 and -1 upon RNA incorporation. Further confounding the issue, the DWV VP4 sequence corresponds to a peptide of 2.3 kDa that is undetectable by PAGE and makes VP1 indistinguishable from VP0. In the absence of any antibodies directed to VP4 to probe the identity of protein bands, we could not yet conclusively identify the proteins by electrophoresis.

The two predominate bands that formed during repeated DWV purifications were similar to those seen as a result of purification for many picornaviruses that assemble both procapsid and infectious virus. Furthermore, the appearance of an empty capsid in the top band persisted, whereas changes to the purification protocol allowed us to capture intact virion in the lower band. However, our conditions need further optimization as RNA-packaged virus converted to capsid forms downstream in the virus life cycle, i.e., a putative A-particle and 80S capsid. Nevertheless, we propose a model for DWV that consists of assembly of both a naturally occurring empty capsid (procapsid) and an RNA-filled infectious virion. Furthermore, DWV likely proceeds with infection through an A-particle intermediate before releasing the genome to leave behind an empty 80S-like capsid. The large conformational changes to the 5-fold spikes that accompany the release of genome suggest that the change has function during host interaction or genome release (Fig. 11).

FIG 11.

Similarly to picornavirus, DWV assembles an empty capsid in addition to RNA-filled capsids. This procapsid structure resembles the infectious virus, whereas the putative A-particle resembles the 80S empty capsid. The putative A-particle and 80S-like empty capsid have different conformations for the 5-fold spikes.

Although it seems that DWV capsids undergo changes similar to those seen with picornaviruses, the structures reveal some notable differences. DWV employs strand swapping to maintain capsid structure, a strong structural feature that occurs across the icosahedral 2-fold axis, which is the proposed site of genome release for picornaviruses (32, 39–41). The site for DWV genome release may be the open pore at the 5-fold vertex. There is a plug of density below the 5-fold vertex at the capsid interior in both capsids; for the 80S-like capsid, however, the density is tethered only loosely. Perhaps the plug of density hanging below the opening was missing altogether at the vertex through which the RNA egressed. The use of a 5-fold pore to package and release the virus genome is a known feature of a parvovirus, minute virus of mice (MVM), another small nonenveloped icosahedral virus (42).

The movement of the spikes from open to closed illustrates a major conformational change that may accompany genome release or host attachment. The spikes in the closed conformation may function as a tube at the 5-fold vertex through which to translocate the RNA. Another insect virus, Helicoverpa armigera stunt virus (HaSV), binds asymmetrically and nonspecifically to host cells to create a pore in the cell membrane and allow genome egress, likely through a modified 5-fold vertex (43, 44). Similarly, the DWV spikes may function during attachment and contribute to the remarkably broad tropism observed for this virus, since DWV can infect myriad bee tissues from the gut to the brain, as well as other species, including the Varroa mite and bumble bees (11, 45–47).

Given the importance of honey bees to global agriculture, continuing structural and molecular genetics research will be imperative for characterizing the DWV pathogen. Solving the atomic resolution structure of the RNA-filled virus is a clear objective, as is understanding the proteolytic status of the VP0 protein and the process of RNA packaging. Beyond that, compelling future directions are to understand the function of elements such as the VP1 C-terminal spikes and to explore the effect on tropism and the process of genome release into the host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Processing of infected honey bees.

In August of 2014, adult worker honey bees with obvious wing deformities were collected from brood combs originating from colonies containing an egg-laying queen (queen-right) in the Bucknell University Apiary and immediately stored at −80°C. Approximately 10 bees with deformed wings were homogenized in a 30% (wt/vol) mixture containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The mixture was clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g in a JS-13 rotor for 15 min at 4°C. A portion of the clarified bee homogenate was passed through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter for further purification. Both filtered and unfiltered bee homogenate were stored at −80°C until they were used for RNA and virion purification.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) detection of virus.

Total RNA was purified from a 400-μl aliquot of the filtered and unfiltered bee homogenate using TRIzol (Invitrogen) followed by a Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit and DNase I treatment (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentrations were measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and confirmed using a Qubit RNA BR assay kit (Invitrogen). A 2-μg volume of total RNA was converted to cDNA using a High Capacity RNA to cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems). RT-PCR was carried out on the cDNA samples using a Roche LightCycler 96 instrument. Each 20-μl reaction mixture contained 1× Fast Start Essential DNA Green Supermix (Roche), a 0.25 μM concentration of primers, and 0.2 μl of cDNA sample and was heated to 95°C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 15 s. Primers used to detect levels of DWV and other honey bee viruses were as follows: DWV-F, 5′-AGCATGGGTGAAGGAATGTC-3′; DWV-R, 5′-ATATGAATGTGCCGCAAACA-3′; ABPV-F, 5′-TGAAACGGAACAAATCACCA-3′; ABPV-R, 5′-GGGGCGTTGTAAAAACTGAA-3′; BQCV-F, 5′-CTCTAAGACAGGCGCAGCTT-3′; BQCV-R, 5′-CGCTCCAGATTTGAGGAAAG-3′; KBV-F, 5′-ATGCAGAGACCGGAGAAAAA-3′; KBV-R, 5′-TGGCAGACTCATCTCGACAC-3′; SBV-F, 5′-GATTGGTTGGTTGCGAAGTT-3′; SBV-R, 5′-CGCAAAGATCCTACCTCAGC-3′; Am-rp49-F, 5′-CGTCATATGTTGCCAACTGGT-3′; and Am-rp49-R, 5′-TTGAGCACGTTCAACAATGG-3′. Negative controls consisted of RNA minus reverse transcriptase.

DWV purification and characterization.

For DWV1 and DWV2, 2 ml of unfiltered DWV-infected bee homogenate was applied to 20 ml of 30% (wt/vol) sucrose–PBS in a red-capped Beckman tube. Viral capsids were pelleted through the sucrose cushion in a 50.2 Ti rotor at 48,000 rpm for 2 h at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 2 ml PBS and transferred to 10% to 35% sucrose (wt/vol)–PBS with a 0.1% Tween gradient for ultracentrifugation in a SW41 rotor for 2 h at 4°C and a speed of 36,000 rpm. Two protein bands were purified, and each band was extracted via side puncture. The material from each band was stored overnight and was washed five times with excess PBS in 10-kDa-cutoff centrifugation filters the following day to remove the sucrose and concentrate each sample for transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Material from each band was stained with 1% uranyl formate (UF) on glow-discharged continuous carbon copper EM grids. Stained samples were imaged at 60-kV accelerating voltage in a JEOL 1400 TEM (Peabody, MA) at the Penn State College of Medicine Imaging Core Facility.

From each of the two gradient bands, a 16-μl aliquot was mixed with 4 μl of 5× Laemmli running buffer and incubated at 95°C for 5 min before transfer to a Mini-Protean TGX precast gel (Bio-Rad). The Precision Plus protein standard (Bio-Rad) was added as a size ladder, and electrophoresis was conducted at 200 V and 30 mA for 40 min. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue.

For the second purification protocol that isolated the RNA-filled virus, 1 ml of DWV-infected bee homogenate was purified and imaged as described above, with the exception that transfer to a 10% to 35% (wt/vol) sucrose in PBS gradient for ultracentrifugation was performed, buffer exchange was to PBS (pH 7.4), and the sample was not stored but was imaged immediately by TEM. After imaging, an aliquot was incubated at 37° for 24 h prior to TEM imaging, vitrification, and cryo-EM data collection.

Microscopy for negative-stain TEM.

For all negative-stain TEM experiments, 3 μl of sample was applied to a freshly glow-discharged continuous carbon-coated copper EM grid negatively stained with 3 μl of uranyl formate. The grids were imaged with a JEOL 2100 (JEOL, Peabody, MA) transmission electron microscope housed in the imaging facility at The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine.

Microscopy for first sample preparation conditions.

For cryo-EM, aliquots of DWV capsids from the top band (DWV1) and lower band (DWV2) were applied to freshly glow-discharged holey carbon Quantifoil EM grids (Quantifoil Micro Tools GmbH, Jena, Germany) to which a thin layer of continuous carbon support film was applied. Grids were blotted and plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a CP3 robot (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA). Vitrified grids were screened for ice quality and sample concentration at the Penn State College of Medicine Imaging Core Facility using a JEOL (Peabody, MA) 2100 LaB6 cryo-electron microscope (cryo-EM).

Grids of virus from DWV1 were cryo-shipped to the University of Virginia School of Medicine Molecular Electron Microscopy Core. Low-dose micrographs were recorded using an FEI (Hillsboro, OR) Titan Krios cryo-EM operating at an accelerating voltage of 300 kV and a nominal magnification of 59,000× with defocus values ranging from −0.74 to −5.58 μm. Data were collected under EPU software control using an FEI Falcon II direct electron detector operating in movie mode. The postcolumn magnification of 1.6× yielded a calibrated pixel size at the sample of 1.40 Å.

Grids from DWV2 were transported to the University of Pittsburgh for data collection using an FEI Polara G2 microscope operating at 300 kV and a nominal magnification of 78,000× with defocus values ranging from −0.19 to −5.76 μm using an FEI Falcon II direct electron detector with postcolumn magnification of 1.4×, yielding a calibrated pixel size at the sample of 1.37 Å.

Microscopy for second sample preparation conditions.

Aliquots from the top band and lower band were imaged by negative staining (see above). A 3.5-μl volume of sample from the lower band was applied to freshly glow-discharged holey carbon Quantifoil EM grids (Quantifoil Micro Tools GmbH, Jena, Germany) to which a thin layer of continuous carbon support film was applied. Grids were blotted and plunge frozen in liquid ethane using a CP3 robot (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA). Vitrified grids from the RNA-filled capsids were recorded at the Penn State College of Medicine Imaging Core Facility under low-dose conditions on an Ultrascan 4000 charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, CA). The JEOL 2100 microscope was operating at 200 kV and was equipped with a Gatan 626 cryo-holder.

Image processing and three-dimensional reconstruction.

Reconstructions for the DWV1 and DWV2 from the first purification and the partially RNA-filled viruses that had been incubated overnight at 37°C were initiated separately with drift correction using the DriftCorr program (48). Defocus estimation was performed with CTFFIND4 (49). Particles were automatically selected from each micrograph using the EMAN2.1 program (50). The selected particles were normalized, linearized, and subjected to apodization prior to image reconstruction. AUTO3DEM operating in “gold standard” mode divided each data set into two halves to generate random models, determine particle orientations, calculate the final reconstructions, and assess the resolution at a Fourier shell correlation (FSC) cutoff value of 0.143 (51) (Table 1). The negative-stain particles were also processed similarly except that the contrast was inverted before initiating auto3DEM.

Fitting analysis and density difference map calculations were completed using Situs and Chimera (52, 53). Handedness of the maps was assigned based on the correlation coefficient of the fitting of the structures into flipped and unflipped maps. Local-resolution estimations were calculated with ResMap (54). Sequence alignments for Fig. 5 and 8 were performed using Clustal-Omega (55). Maps of slow bee paralysis virus were generated from the crystal structures (PDB identifiers [ID] 5J96 and 5J98) using pdb2vol from the Situs package with a Gaussian smoothing kernel, a resolution value of 7 Å, and a pixel value of 1.37 Å/pixel (52). The crystal structures (PDB ID 5J96 and 5J98) were fitted into DWV1 and DWV2 using Chimera fit-in-map with icosahedral symmetry operators applied to generate all 60 asymmetric units.

Accession number(s).

The cryo-EM maps for the DWV1 and DWV2 were deposited in the EM data bank (www.emdatabank.org/) under accession numbers EMD-8463 and EMD-8464, respectively.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by Pennsylvania Department of Health CURE funds. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, under awards S10OD019995 and S10OD011986, as well as NIH grants R01AI107121 (S.H.) and T32CA060395 (L.J.O.). The UVA MEMC equipment was partially funded by grants from the NIH for the Titan Krios (S10-RR025067) and the Falcon II direct detector (S10-OD018149).

The content is solely our responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

We declare that we have no potential conflicts of interest.

L.J.O. and K.L.S. prepared all samples for cryo-EM and data collection. K.L.S. and K.D. performed proof-of-principle experiments. R.E.A. collected negative-stain and LaB6 data and analyzed initial data. E.A.C. and M.C.P. provided DWV-infected honey bees and performed molecular biological assays. K.A.D., A.M.M., and J.F.C. acquired and interpreted cryo-EM data. L.J.O. performed cryo-EM and negative-stain image processing and model prediction, S.H. and L.J.O. analyzed the data and interpreted the structures. L.J.O., K.L.S., J.F.C, M.C.P., and S.H. oversaw the project and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01795-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans JD, Schwarz RS. 2011. Bees brought to their knees: microbes affecting honey bee health. Trends Microbiol 19:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potts SG, Biesmeijer JC, Kremen C, Neumann P, Schweiger O, Kunin WE. 2010. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol Evol 25:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Engelsdorp D, Hayes J, Underwood RM, Pettis J. 2008. A survey of honey bee colony losses in the U.S., fall 2007 to spring 2008. PLoS One 3:e4071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Genersch E, Aubert M. 2010. Emerging and re-emerging viruses of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). Vet Res 41:54. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mondet F, de Miranda JR, Kretzschmar A, Le Conte Y, Mercer AR. 2014. On the front line: quantitative virus dynamics in honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies along a new expansion front of the parasite Varroa destructor. PLoS Pathog 10:e1004323. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson RM, Evans JD, Robinson GE, Berenbaum MR. 2009. Changes in transcript abundance relating to colony collapse disorder in honey bees (Apis mellifera). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:14790–14795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906970106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dainat B, Evans JD, Chen YP, Gauthier L, Neumann P. 2012. Predictive markers of honey bee colony collapse. PLoS One 7:e32151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder DC, Martin SJ. 2012. Deformed wing virus: the main suspect in unexplained honeybee deaths worldwide. Virulence 3:589–591. doi: 10.4161/viru.22219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dainat B, Neumann P. 2013. Clinical signs of deformed wing virus infection are predictive markers for honey bee colony losses. J Invertebr Pathol 112:278–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Möckel N, Gisder S, Genersch E. 2011. Horizontal transmission of deformed wing virus: pathological consequences in adult bees (Apis mellifera) depend on the transmission route. J Gen Virol 92:370–377. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.025940-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisder S, Aumeier P, Genersch E. 2009. Deformed wing virus: replication and viral load in mites (Varroa destructor). J Gen Virol 90:463–467. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.005579-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzei M, Carrozza ML, Luisi E, Forzan M, Giusti M, Sagona S, Tolari F, Felicioli A. 2014. Infectivity of DWV associated to flower pollen: experimental evidence of a horizontal transmission route. PLoS One 9:e113448. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen YP, Pettis JS, Collins A, Feldlaufer MF. 2006. Prevalence and transmission of honeybee viruses. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:606–611. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.606-611.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yue C, Schroder M, Gisder S, Genersch E. 2007. Vertical-transmission routes for deformed wing virus of honeybees (Apis mellifera). J Gen Virol 88:2329–2336. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey L, Ball BV. 1991. Honey bee pathology, 2nd ed Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ball BV, Bailey L. Viruses, p 11–31. In Honey bee pests, predators, and diseases, 3rd ed A. I. Root, Medina, OH. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanzi G, de Miranda JR, Boniotti MB, Cameron CE, Lavazza A, Capucci L, Camazine SM, Rossi C. 2006. Molecular and biological characterization of deformed wing virus of honeybees (Apis mellifera L.). J Virol 80:4998–5009. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4998-5009.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ongus JR, Roode EC, Pleij CWA, Vlak JM, van Oers MM. 2006. The 5′ non-translated region of Varroa destructor virus 1 (genus Iflavirus): structure prediction and IRES activity in Lymantria dispar cells. J Gen Virol 87:3397–3407. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liljas L, Tate J, Lin T, Christian P, Johnson JE. 2002. Evolutionary and taxonomic implications of conserved structural motifs between picornaviruses and insect picorna-like viruses. Arch Virol 147:59–84. doi: 10.1007/s705-002-8303-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sánchez-Eugenia R, Goikolea J, Gil-Cartón D, Sánchez-Magraner L, Guérin DMA. 2015. Triatoma virus recombinant VP4 protein induces membrane permeability through dynamic pores. J Virol 89:4645–4654. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00011-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu L, Wang X, Ren J, Porta C, Wenham H, Ekström J-O, Panjwani A, Knowles NJ, Kotecha A, Siebert CA, Lindberg AM, Fry EE, Rao Z, Tuthill TJ, Stuart DI. 2015. Structure of Ljungan virus provides insight into genome packaging of this picornavirus. Nat Commun 6:8316. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalynych S, Přidal A, Pálková L, Levdansky Y, de Miranda JR, Plevka P. 2016. Virion structure of Iflavirus slow bee paralysis virus at 2.6-angstrom resolution. J Virol 90:7444–7455. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00680-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agirre J, Aloria K, Arizmendi JM, Iloro I, Elortza F, Sánchez-Eugenia R, Marti GA, Neumann E, Rey FA, Guérin DMA. 2011. Capsid protein identification and analysis of mature Triatoma virus (TrV) virions and naturally occurring empty particles. Virology 409:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agirre J, Goret G, LeGoff M, Sanchez-Eugenia R, Marti GA, Navaza J, Guerin DMA, Neumann E. 2013. Cryo-electron microscopy reconstructions of triatoma virus particles: a clue to unravel genome delivery and capsid disassembly. J Gen Virol 94:1058–1068. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.048553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cifuente JO, Lee H, Yoder JD, Shingler KL, Carnegie MS, Yoder JL, Ashley RE, Makhov AM, Conway JF, Hafenstein S. 2013. Structures of the procapsid and mature virion of enterovirus 71 strain 1095. J Virol 87:7637–7645. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03519-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips BA, Fennell R. 1973. Polypeptide composition of poliovirions, naturally occurring empty capsids, and 14S precursor particles. J Virol 12:291–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shingler KL, Organtini LJ, Hafenstein S. 2014. Enterovirus 71 virus propagation and purification. Bio-Protoc 4:pii:e1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li C, Wang JC-Y, Taylor MW, Zlotnick A. 2012. In vitro assembly of an empty picornavirus capsid follows a dodecahedral path. J Virol 86:13062–13069. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01033-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simons KT, Kooperberg C, Huang E, Baker D. 1997. Assembly of protein tertiary structures from fragments with similar local sequences using simulated annealing and Bayesian scoring functions. J Mol Biol 268:209–225. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradley P, Misura KMS, Baker D. 2005. Toward high-resolution de novo structure prediction for small proteins. Science 309:1868–1871. doi: 10.1126/science.1113801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Miranda JR, Dainat B, Locke B, Cordoni G, Berthoud H, Gauthier L, Neumann P, Budge GE, Ball BV, Stoltz DB. 2010. Genetic characterization of slow bee paralysis virus of the honeybee (Apis mellifera L.). J Gen Virol 91:2524–2530. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.022434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shingler KL, Yoder JL, Carnegie MS, Ashley RE, Makhov AM, Conway JF, Hafenstein S. 2013. The enterovirus 71 A-particle forms a gateway to allow genome release: a cryoEM study of picornavirus uncoating. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003240. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Organtini LJ, Makhov AM, Conway JF, Hafenstein S, Carson SD. 2014. Kinetic and structural analysis of coxsackievirus B3 receptor interactions and formation of the A-particle. J Virol 88:5755–5765. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00299-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butan C, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2014. Cryo-electron microscopy reconstruction shows poliovirus 135S particles poised for membrane interaction and RNA release. J Virol 88:1758–1770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01949-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujiyuki T, Takeuchi H, Ono M, Ohka S, Sasaki T, Nomoto A, Kubo T. 2004. Novel insect picorna-like virus identified in the brains of aggressive worker honeybees. J Virol 78:1093–1100. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1093-1100.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rortais A, Tentcheva D, Papachristoforou A, Gauthier L, Arnold G, Colin ME, Bergoin M. 2006. Deformed wing virus is not related to honey bees' aggressiveness. Virol J 3:61. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iqbal J, Mueller U. 2007. Virus infection causes specific learning deficits in honeybee foragers. Proc Biol Sci 274:1517–1521. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren J, Wang X, Hu Z, Gao Q, Sun Y, Li X, Porta C, Walter TS, Gilbert RJ, Zhao Y, Axford D, Williams M, McAuley K, Rowlands DJ, Yin W, Wang J, Stuart DI, Rao Z, Fry EE. 2013. Picornavirus uncoating intermediate captured in atomic detail. Nat Commun 4:1929. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bostina M, Levy H, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2011. Poliovirus RNA is released from the capsid near a twofold symmetry axis. J Virol 85:776–783. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00531-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Peng W, Ren J, Hu Z, Xu J, Lou Z, Li X, Yin W, Shen X, Porta C, Walter TS, Evans G, Axford D, Owen R, Rowlands DJ, Wang J, Stuart DI, Fry EE, Rao Z. 2012. A sensor-adaptor mechanism for enterovirus uncoating from structures of EV71. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:424–429. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar M, Blaas D. 2013. Human rhinovirus subviral A particle binds to lipid membranes over a twofold axis of icosahedral symmetry. J Virol 87:11309–11312. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02055-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plevka P, Hafenstein S, Li L, D'Abrgamo A, Cotmore SF, Rossmann MG, Tattersall P. 2011. Structure of a packaging-defective mutant of minute virus of mice indicates that the genome is packaged via a pore at a 5-fold axis. J Virol 85:4822–4827. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02598-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kearney B, Johnson J. 2014. Assembly and maturation of a T = 4 quasi-equivalent virus is guided by electrostatic and mechanical forces. Viruses 6:3348–3362. doi: 10.3390/v6083348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Domitrovic T, Movahed N, Bothner B, Matsui T, Wang Q, Doerschuk PC, Johnson JE. 2013. Virus assembly and maturation: auto-regulation through allosteric molecular switches. J Mol Biol 425:1488–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shah KS, Evans EC, Pizzorno MC. 2009. Localization of deformed wing virus (DWV) in the brains of the honeybee, Apis mellifera Linnaeus. Virol J 6:182. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fürst MA, McMahon DP, Osborne JL, Paxton RJ, Brown MJF. 2014. Disease associations between honeybees and bumblebees as a threat to wild pollinators. Nature 506:364–366. doi: 10.1038/nature12977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fievet J, Tentcheva D, Gauthier L, de Miranda J, Cousserans F, Colin ME, Bergoin M. 2006. Localization of deformed wing virus infection in queen and drone Apis mellifera L. Virol J 3:16. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li X, Mooney P, Zheng S, Booth CR, Braunfeld MB, Gubbens S, Agard DA, Cheng Y. 2013. Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nat Methods 10:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rohou A, Grigorieff N. 2015. CTFFIND4: fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol 192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang G, Peng L, Baldwin PR, Mann DS, Jiang W, Rees I, Ludtke SJ. 2007. EMAN2: an extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J Struct Biol 157:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan X, Sinkovits RS, Baker TS. 2007. AUTO3DEM—an automated and high throughput program for image reconstruction of icosahedral particles. J Struct Biol 157:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wriggers W, Chacón P. 2001. Modeling tricks and fitting techniques for multiresolution structures. Structure 9:779–788. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ, Tagare HD. 2014. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat Methods 11:63–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:539–539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.