ABSTRACT

Marburg virus (MARV) is a highly pathogenic filovirus that is classified in a genus distinct from that of Ebola virus (EBOV) (genera Marburgvirus and Ebolavirus, respectively). Both viruses produce a multifunctional protein termed VP35, which acts as a polymerase cofactor, a viral protein chaperone, and an antagonist of the innate immune response. VP35 contains a central oligomerization domain with a predicted coiled-coil motif. This domain has been shown to be essential for RNA polymerase function. Here we present crystal structures of the MARV VP35 oligomerization domain. These structures and accompanying biophysical characterization suggest that MARV VP35 is a trimer. In contrast, EBOV VP35 is likely a tetramer in solution. Differences in the oligomeric state of this protein may explain mechanistic differences in replication and immune evasion observed for MARV and EBOV.

IMPORTANCE Marburg virus can cause severe disease, with up to 90% human lethality. Its genome is concise, only producing seven proteins. One of the proteins, VP35, is essential for replication of the viral genome and for evasion of host immune responses. VP35 oligomerizes (self-assembles) in order to function, yet the structure by which it assembles has not been visualized. Here we present two crystal structures of this oligomerization domain. In both structures, three copies of VP35 twist about each other to form a coiled coil. This trimeric assembly is in contrast to tetrameric predictions for VP35 of Ebola virus and to known structures of homologous proteins in the measles, mumps, and Nipah viruses. Distinct oligomeric states of the Marburg and Ebola virus VP35 proteins may explain differences between them in polymerase function and immune evasion. These findings may provide a more accurate understanding of the mechanisms governing VP35's functions and inform the design of therapeutics.

KEYWORDS: VP35, filovirus, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, phosphoprotein, coiled coil, oligomerization, Marburg virus, Ebola virus, X-ray crystallography

INTRODUCTION

Marburg virus (MARV) can cause severe hemorrhagic fever in humans with high case fatality rates. Though less well known than its relative Ebola virus (EBOV), MARV was the first filovirus identified. MARV has caused sporadic outbreaks since its identification in 1968, including the 1998 to 2000 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which occurred with 83% lethality, and the 2004 to 2005 outbreak in Angola, which occurred with 90% lethality (1). Currently, there are no approved vaccines or therapeutics available to treat individuals infected with MARV. Despite sharing ∼50% nucleotide sequence identity, MARV and EBOV have several striking functional differences. MARV does not produce sGP or ssGP protein and does not require VP30 for transcription. MARV and EBOV also exhibit differences in their immune evasion strategies (2).

MARV and EBOV are both members of the Filoviridae family, which is a member of the Mononegavirales order. Other members of this order important for human health include the measles, mumps, Nipah, and rabies viruses. Mononegaviruses are nonsegmented, negative-strand RNA viruses (NNSVs). NNSVs encode a viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) to transcribe their mRNAs and replicate their genomes. The filovirus RdRp is composed of two viral proteins: large protein (L) and VP35. L contains all of the enzymatic activity required for RNA transcription and replication. Filovirus VP35 is an essential polymerase cofactor homologous to the phosphoprotein (P) of other mononegaviruses. Interestingly, filovirus VP35 proteins are not highly phosphorylated like other phosphoprotein homologs (3, 4). The genomes of NNSVs are never found as naked RNAs in virions or infected cells (5–7). Instead, they are completely encapsidated by the viral nucleoprotein (5–7), termed NP in the case of filoviruses and N in other NNSVs. In filoviruses, this NP-encapsidated RNA scaffolds three other viral proteins, VP30, VP35, and L, to form a ribonucleoprotein complex termed the nucleocapsid (NC). The NC acts as the template for the viral polymerase (5–7). The polymerase cofactor, VP35, is required for recruitment of L to this structure (8) and for the efficient synthesis of RNA (4, 9). Mühlberger et al. found that L, NP, and VP35 could not support RNA synthesis when one of these proteins was exchanged between MARV and EBOV (4, 9). The specific requirement for each virus's own proteins emphasizes the specificity of the MARV and EBOV replication strategies and implies physical differences in the replication machinery.

The mononegavirus polymerase cofactor (VP35 for filoviruses) is composed of three modular domains: an N-terminal chaperoning peptide, a central oligomerization domain, and a C-terminal domain (CTD) (Fig. 1A). In addition to their role as polymerase cofactors, these proteins have several other functions in the viral life cycle. The first is chaperoning newly synthesized nucleoproteins to ensure that they only oligomerize on and encapsidate viral genomic or antigenomic RNA. This chaperoning function is accomplished through the N-terminal peptide of VP35 or P. Structures of this peptide bound to RNA-free NP or N have been determined for many mononegaviruses, including EBOV (10, 11). VP35 has an additional binding site for NP located in its CTD, which likely facilitates the tethering of L to the helical nucleocapsid (12).

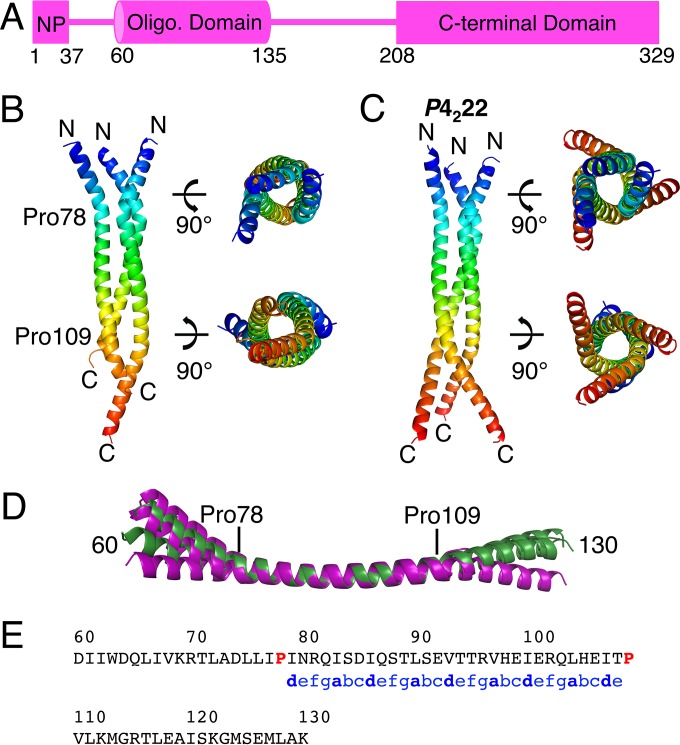

FIG 1.

Structure of the MARV VP35 oligomerization domain. (A) MARV VP35 is composed of modular domains (boxes) connected by disordered linkers (lines). The N-terminal region (residues 1 to 24 and 32 to 44) is likely involved in the chaperoning of NP based on homology to EBOV VP35 (10, 11). Residues 60 to 135 make up the oligomerization domain, and residues 208 to 329 make up the CTD. (B) The crystal structure of the MARV VP35 oligomerization domain derived from the I2 space group is shown in cartoon form, colored as a rainbow transitioning from blue (N termini) to red (C termini). Residue numbers and the prolines flanking the traditional coiled coil are indicated. (C) A second crystal structure of the oligomerization domain derived from the P4222 space group is depicted here. (D) Each unique chain from the two crystal structures is aligned in this panel. The three chains from the I2 space group are purple, and the three chains from the P4222 space group are green. Residue numbers are indicated. Note that only one of the chains in the I2 structure (purple) has an ordered C terminus; the others are disordered. (E) The amino acid sequence of the oligomerization domain is shown. The heptad repeat is annotated with lowercase letters, and knob positions (a and d) are in bold. The flanking prolines (residues 78 and 109) are red.

VP35 and P are also potent inhibitors of the innate immune response, although evasion mechanisms vary across Mononegavirales. In the case of filoviruses, VP35 blocks the production of α/β interferon by antagonizing retinoic acid-inducible gene 1 (RIG-I)-like receptor signaling (13). The CTD of VP35 binds double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), a potent activator of the innate immune response that is produced during the replication of RNA viruses (13). By binding dsRNA, VP35 blocks viral detection by cellular immune sensors such as RIG-I. Several crystal structures of the CTD, alone and in complex with dsRNA, have been solved (14–21). Though the folds of the CTDs of the Marburgvirus and Ebolavirus VP35 proteins are nearly identical, there are clear differences in the RNA-binding preferences of the two VP35 proteins. Ebolavirus VP35 proteins initiate binding by forming a dimer to cap the ends of dsRNA before coating the dsRNA backbone (14, 17, 19–21). No such dimer has been observed in any of the MARV VP35 structures solved to date, and MARV VP35 does not require capping in order to coat dsRNA (14, 16).

VP35 of both pathogenic (EBOV) and nonpathogenic (Reston virus) EBOVs potently inhibit interferon production in cells, and oligomerization of VP35 is required for potent interferon antagonism in all of the EBOVs studied (16, 22). In contrast, MARV VP35 is a much less potent antagonist of interferon production and oligomerization of MARV VP35 does not provide enhancement of potency as it does for EBOVs (16, 22).

Oligomerization is, however, essential for the function of both the MARV and EBOV VP35 proteins as polymerase cofactors. Filovirus VP35 proteins contain a predicted coiled-coil domain, and homo-oligomers of MARV VP35 are essential for proper recruitment of L to the NC (23). The oligomeric state of EBOV VP35 is thought to be tetrameric, based on light scattering data collected on either the isolated oligomerization domain of EBOV VP35 or full-length EBOV VP35 fused to maltose-binding protein (MBP) (22, 24). The oligomeric state of MARV VP35 has been suggested to also be a tetramer in solution based on light scattering data of full-length VP35 similarly fused to MBP (22). However, no VP35 oligomerization domain of any filovirus has yet been structurally characterized.

Here we describe two crystal structures of the MARV VP35 oligomerization domain, in different space groups and with distinct crystal packing arrangements. Both structures reveal a trimeric coiled coil, in contrast to the previous tetrameric predictions. These structures and accompanying biochemical analysis suggest that MARV and EBOV may indeed oligomerize differently: MARV as a trimer and EBOV as a tetramer. This work may provide clarity to the differences in replication strategies and dsRNA-binding properties of these two proteins and provides a template for exploration of the role of oligomerization in the multiple functions of VP35 in viral life cycles.

RESULTS

Trimeric structure of the MARV VP35 oligomerization domain.

The oligomerization domain of MARV VP35 forms an elongated, trimeric coiled coil in two different crystal structures (Fig. 1B and C). In the I2 space group, three chains are visible in the asymmetric unit, though these chains differ in the number of residues visible in the electron density (Fig. 1B). In chain B, most of the residues (60 to 128) are resolved. In chains A and C, density is missing for amino acids C terminal to residues 110 and 115, respectively, suggesting disorder/flexibility of these termini or degradation of the protein in the crystallization experiment. In a P4222 space group, this domain also crystallizes as a long, trimeric coiled coil. The P4222 crystal structure is also composed of one trimer in the asymmetric unit, and the majority of residues are resolved in all chains (Fig. 1C). These two structures are highly similar (Fig. 1D). The root mean square deviation (RMSD) for all atoms between any two single chains falls between 0.5 and 2 Å, while the trimer from the I2 space group superimposed on the trimer from the P4222 space group has an RMSD of 2.4 Å. The largest differences are observed in the N and C termini: before proline 78 and after proline 109 (Fig. 1D), while the central trimeric coiled coil is quite similar.

This region, between residues 79 and 108 of MARV VP35, forms a classical trimeric coiled coil according to analysis by coiled-coil Crick parameterization (25) and SOCKET (26) (Fig. 1E). The helical properties of this coil are typical of trimeric coiled coils, and all “knob” residues are leucines, isoleucines, or valines, as expected (25). Two prolines (78 and 109) flank the coiled coil, and these prolines are conserved among strains of MARV. Most VP35 proteins of the ebolaviruses (Ebola, Sudan, Bundibugyo, Taï Forest, and Reston viruses) display a similar pattern of prolines (residues 77 and 120 in EBOV) that flank a predicted coiled-coil region, although very little sequence identity exists within that coiled coil (18% compared to 33% for the entire protein). The predicted coiled coil of the EBOVs is also 12 residues longer than that of MARV (27).

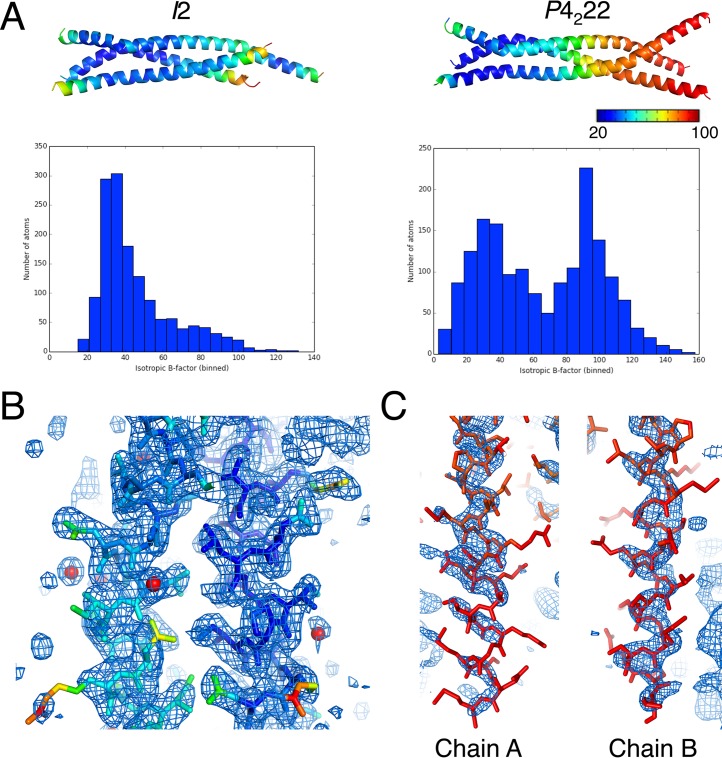

The resolution and quality of the electron density map vary greatly across the P4222 structure, with residues 60 to 109 being generally better ordered than residues 110 to 130. The overall average B factor of this structure is 66 Å2. However, the spread of B factors exhibits a bimodal distribution, with the first peak around 30 Å2 and a second peak around 90 Å2. Solvent molecules, with an average B factor of 41 Å2, were only modeled in regions with lower protein B factors. B factors and selected images of electron density maps are shown in Fig. 2.

FIG 2.

Variation in order throughout the VP35 structures. (A) The two structures of the MARV VP35 oligomerization domain are colored by B factor along with graphs representing the distributions of B factors for each structure. The P4222 structure contains a bimodal distribution of B factors, with the C termini generally being more disordered than the coiled-coil core of the protein. (B) Representative image of the electron density (2mFo-DFc map, σ = 1.0) from the P4222 structure in the more ordered N-terminal region. Water molecules are shown as red spheres. (C) Images of the poor electron density (2mFo-DFc map, σ = 1.0) observed for the C termini of this domain in the P4222 structure. Two chains (A and B) with various degrees of map quality are displayed.

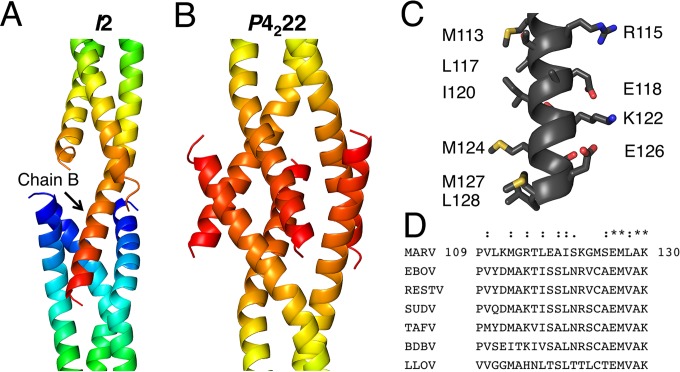

The VP35 crystal lattices derived from the I2 and P4222 space groups are built from unusually intimate but distinct crystal contacts. The N-terminal ends of the coiled coils pack against one another with similar contacts in both space groups (contacts not shown), while the C-terminal ends make distinct contacts. In the I2 space group, the C-terminal peptide from chain B inserts itself into the N-terminal helical bundle from an adjacent trimer in the crystal lattice (Fig. 3A). The inserting C-terminal helix and the adjacent trimer together form an intimate four-helix bundle. In the P4222 space group, the corresponding C-terminal helix instead mediates contacts with the C-terminal helices of a second trimer in the crystal lattice. These C-terminal helices from two different trimers interdigitate with one another, forming a hollow structure (Fig. 3B). This C-terminal helix (residues 109 to 130) is amphipathic in nature, with a charged/polar face and a hydrophobic face (Fig. 3C). The sequence conservation for this peptide is quite high across Filoviridae (Fig. 3D). These crystal-packing motifs allow for the burial of the highly hydrophobic face of this peptide and are likely entropically favored.

FIG 3.

Intimate crystal contacts mediated by an amphipathic C-terminal peptide. (A) In the I2 space group, extensive crystal packing contacts are mediated by the C terminus of chain B inserting itself into the N-terminal helical bundle of the next trimer in the crystal lattice. This creates a four-helix bundle. The A and C chain C termini are not observed in the electron density maps. (B) In the P4222 space group, the C-terminal peptide also forms intimate crystal contacts with a symmetry-related trimer. However, in the case of the P4222 structure, these C-terminal peptides interdigitate with one another, forming a hollow structure that is different from the packing seen in the I2 space group. (C) The side chains in the C-terminal peptide are shown as sticks in this panel, and selected hydrophobic and charged residues are labeled to emphasize the amphipathic nature of this peptide. (D) Sequence alignment of this VP35 peptide across the members of the family Filoviridae.

Confirmation that EBOV VP35 is a tetramer in solution.

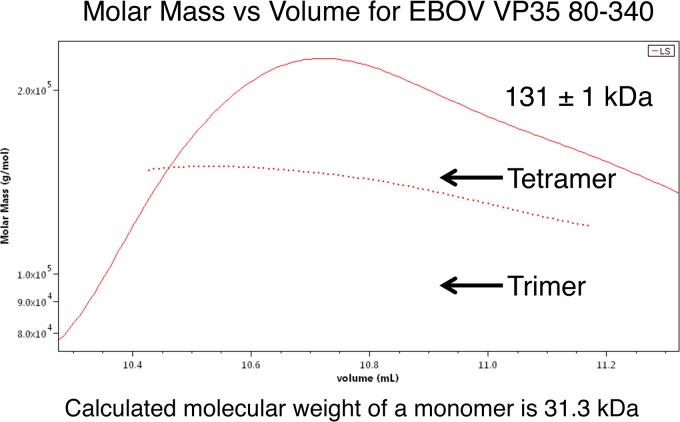

The oligomeric state of EBOV VP35 residues 80 to 340 was determined by size exclusion chromatography coupled with multiangle light scattering (SEC/MALS) (Fig. 4). This protein was found to have a molecular mass of 131 ± 1 kDa. The calculated molecular mass of a monomer is 31.3 kDa, and therefore, the theoretical molecular mass of a trimer is 94 kDa and that of a tetramer is 125 kDa. The experimentally observed molecular mass is most consistent with a tetrameric oligomeric state.

FIG 4.

EBOV VP35 is a tetramer in solution. SEC/MALS data for EBOV VP35 residues 80 to 340 are shown. The molecular mass of this protein was observed to be 131 ± 1 kDa, which is consistent with a tetramer.

The oligomerization domain of MARV VP35 is highly thermostable.

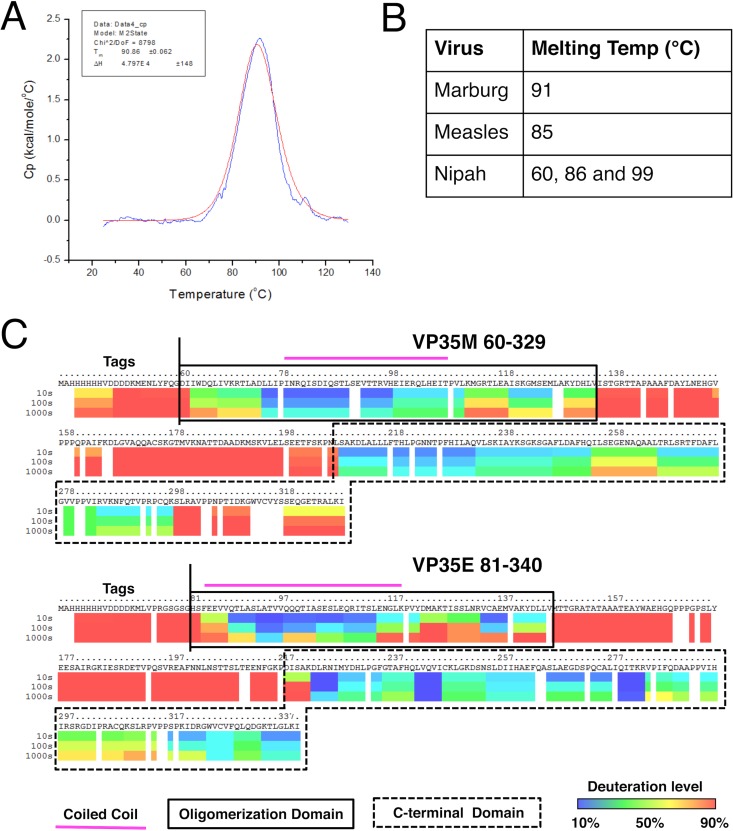

The melting temperature of MARV VP35's oligomerization domain (residues 60 to 130) was determined by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). This protein unfolded with a single transition at 90.86 ± 0.06°C (Fig. 5A). This temperature is comparable to the melting temperatures of the oligomerization domains of other mononegaviruses (Fig. 5B).

FIG 5.

Stability and organization of VP35. (A) The thermal stability of the oligomerization domain of MARV VP35 was assessed by DSC. Normalized molar heat capacity (Cp) is plotted over a range of 25 to 130°C. The raw data are blue, and the two-state transition fit (folded to unfolded) is red. (B) Melting temperature of the MARV VP35 oligomerization domain compared to those of the measles virus (29) and Nipah virus (28) phosphoprotein oligomerization domains. (C) The extent of secondary structure found in VP35 was assessed by DXMS. The oligomerization domains of MARV and EBOV are defined on the basis of these data, showing that residues 60 to 135 and 83 to 145, respectively, are protected from backbone amide exchange. The coiled-coil regions of the oligomerization domains, as observed in the MARV crystal structures and predicted for EBOV VP35 (27), are indicated by the magenta bar. The MARV and EBOV VP35 CTDs, as observed in crystal structures (residues 209 to 329 and 218 to 340, respectively), are denoted by boxes.

The modular organization of VP35 proteins is conserved across filoviruses.

The organization and extent of secondary structure present in VP35 were assessed by hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (DXMS). Backbone amide hydrogens in protein regions forming secondary structure are protected from exchange with solvent and therefore show less deuteration. The constructs used in this assay lack the N termini of VP35 (residues 1 to 59 of MARV and 1 to 80 of EBOV) to aid in the production of nonaggregated recombinant protein. Although the oligomeric states appear to differ, both proteins show a similar modular organization of ordered domains with an internal oligomerization domain and a CTD separated by a long disordered region. MARV VP35 is protected from extensive solvent exchange between residues 60 and 135 and between residues 209 and 298, and EBOV VP35 is protected from extensive solvent exchange between residues 83 and 145 and between residues 208 and 340 (Fig. 5C). These DXMS data suggest that there are five additional ordered residues in the oligomerization domain of MARV VP35 that extend past those included in the crystallized protein construct. Unexpectedly, the DXMS data indicate rapid exchange in the ultimate C terminus (residues 299 to 329) of MARV VP35 but not that of EBOV VP35. This is surprising, given that ordered density is observed in this region of all of the MARV CTD crystal structures solved to date, including RNA-bound and unbound structures (15, 16).

DISCUSSION

VP35 is a multifunctional protein that is essential for the propagation of both MARV and EBOV. These viruses are related, but a growing body of evidence suggests that they have important differences, especially with regard to the roles of VP35 in the virus life cycle. This study provides structural and biophysical evidence of the differences and similarities between the MARV and EBOV VP35 proteins in an effort to better understand the virus-specific functions of the multifunctional VP35 protein.

The crystal structures of the MARV VP35 oligomerization domain reveal a long, trimeric coiled coil (Fig. 1B and C). Two independent structures, from unrelated crystal lattices, display the same tertiary organization, suggesting that this trimer represents the biological assembly of this domain. The extremely high melting temperature, 91°C, of the oligomerization domain of MARV VP35 and the fact that when heated, this domain only undergoes a single transition (folded to unfolded) suggest that this trimer is stable in solution (Fig. 5A). A lower melting temperature would be expected if this domain exchanged between oligomeric states in solution. This observation is in agreement with paramyxovirus P oligomerization domains, which also form long coiled coils and are highly thermally stable (Fig. 5B) (28, 29).

Despite some differences in function and oligomerization between the MARV and EBOV VP35 proteins, the DXMS data suggest that these proteins have similar domain architectures. Both proteins contain a stable coiled-coil oligomerization domain and a folded CTD connected by a long, disordered linker (Fig. 5C). The linker connecting the oligomerization domain and the CTD rapidly exchanges with the solvent for both viruses, suggesting that this region is disordered in solution and that these domains are independent of one another. These data are in good agreement with previous DXMS studies of EBOV VP35 (20) and the ordered regions visible in available crystal structures. The lack of ordered residues connecting the oligomerization domain to the CTD in full-length VP35 suggests that these two domains are independent in nature and that the oligomerization domain likely dictates the overall oligomeric state of full-length VP35.

The trimeric organization of MARV VP35 was unexpected, given the predicted tetrameric organization of EBOV VP35 (22, 24). In light of this discrepancy, we sought to investigate the oligomeric state of EBOV VP35. Our light scattering data collected from EBOV VP35 residues 80 to 340 (Fig. 4) indicates that this protein forms a tetramer in solution, in agreement with earlier studies (22, 24). Thus, these data suggest that the VP35 proteins from MARV and EBOV indeed have different oligomeric states. It is possible that these differences in oligomeric state contribute to the previously observed inability of these proteins to be exchanged in minigenome experiments (9). These polymerase complexes may require a specific oligomeric state of VP35 (trimer versus tetramer), making them incompatible for substitution. Further, differences in the oligomeric states of the MARV and EBOV VP35 proteins may contribute to the observed variations in RNA binding preferences. EBOV VP35 binds RNA in a cooperative manner, utilizing an asymmetric dimer of CTDs to cap blunt-ended RNA termini (20, 21), but MARV VP35 has not been shown to form these dimers in crystal structures (15, 16). It is possible that a tetrameric VP35 is better adapted to form these CTD dimers because of the slightly increased avidity that would be facilitated by the higher oligomeric state of the overall protein.

The oligomerization domains of both the MARV and EBOV VP35 proteins are composed of coiled coils flanked at both ends by proline residues and additional helical secondary structures. In the MARV structure, the long α-helix bends at both of these two prolines, with a large variability in the bend angle among all of the chains observed (Fig. 1D). These coiled-coil flanking prolines are conserved across MARVs and most of the EBOVs, suggesting that these hinge points may be functionally important.

The MARV VP35 oligomerization domain structure also reveals an amphipathic helix at the C terminus of this domain (residues 109 to 130) (Fig. 3C). The burial of the hydrophobic face of this peptide is likely entropically favored but not satisfied in the context of a free trimerization domain, thus leading to the intimate interactions observed in both crystal lattices (Fig. 3A and B). Further, this helical peptide is likely mobile in solution, as it is disordered in two of the three chains in the I2 crystal structure (Fig. 1B). The angle between this peptide and the ridged coiled-coil region varies by 14° between individual chains in these crystal structures, with proline 109 acting as a hinge point (Fig. 1D). This conserved (Fig. 3D), mobile peptide may therefore be a site of protein-protein interactions for an unknown binding partner.

In conclusion, we present the first structure of the trimeric oligomerization domain of MARV VP35 and suggest that full-length MARV VP35 is likely a trimer in solution. This sets MARV apart from the likely tetrameric EBOV VP35 protein and may explain some of the observed functional differences between these two viruses. Despite these differences, the overall domain architecture of this protein appears to be conserved across the filoviruses and NNSVs. These two proteins are capable of performing the same functions in the virus life cycle, but data presented here may better clarify mechanistic differences between the MARV and EBOV VP35 proteins.

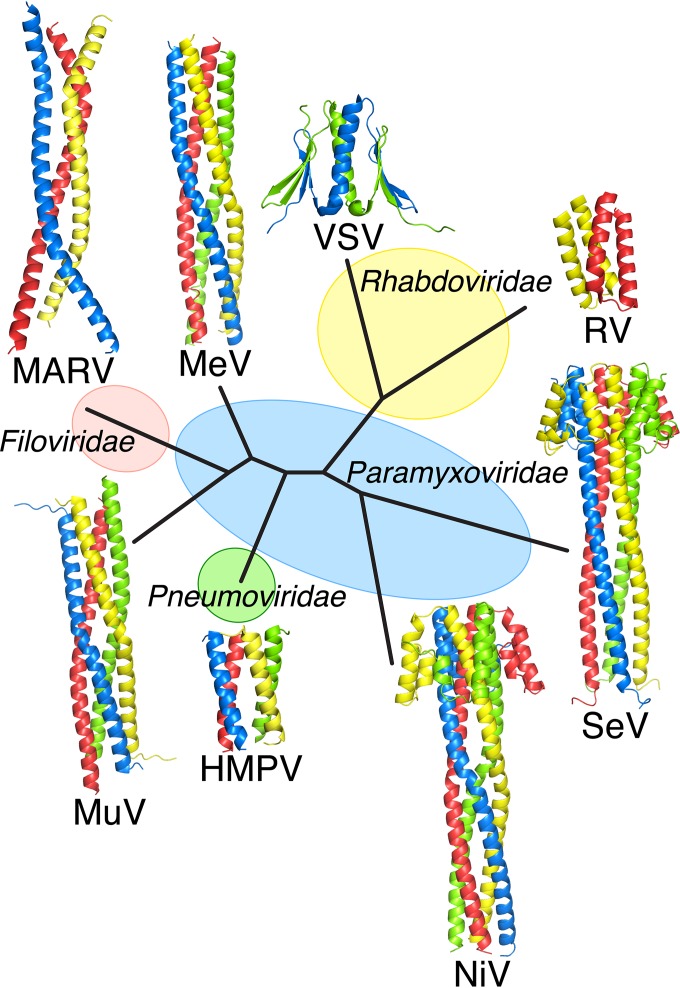

Although all of the oligomerization domains of mononegaviruses solved to date involve helical interactions, they differ in the oligomeric state and the type of interactions observed (Fig. 6). The rhabdovirus P proteins form dimers, although the nature of these dimers is quite variable in that rabies virus P dimerizes by using a simple helical hairpin while vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) dimerizes via a strand swap dimer containing both α-helices and β-strands. In contrast, paramyxovirus P proteins have thus far been observed to form tetramers, although they differ in their orientation (parallel or antiparallel) and whether or not they contain a cap structure. MARV VP35 represents the first NNSV that forms a trimeric polymerase cofactor.

FIG 6.

Structure-based phylogenetic tree of mononegavirus phosphoprotein oligomerization domains. The available experimentally determined structures of mononegavirus phosphoprotein/VP35 oligomerization domains were used to generate a structure-based phylogenetic tree. The structures of the rhabdoviruses rabies virus (RV; PDB code 3L32) and VSV (PDB code 2FQM); the paramyxoviruses measles virus (MeV; PDB code 3ZDO), Sendai virus (SeV), (PDB code 1EZJ), Nipah virus (NiV; PDB code 4N5B), and mumps virus (MuV; PDB code 4EIJ); the pneumovirus human metapneumovirus (HMPV; PDB code 4BXT); and the filovirus MARV (PDB code 5TOI) were used to generate this tree. Alignments and evolutionary distances were derived with the Structure Homology Program (49) and plotted with PHYLIP (50).

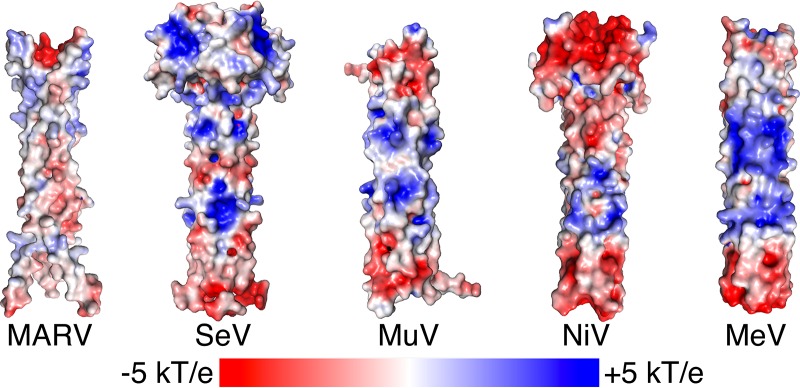

Though filoviruses are thought to be closely related to paramyxoviruses, MARV VP35 further deviates from paramyxovirus structures in its lack of a central basic patch (Fig. 7). This conserved basic patch has been shown to be essential for polymerase function in Sendai (30) and mumps (31) viruses, suggesting that filoviruses and paramyxoviruses have distinct replication strategies. Though the structural nature of the polymerase cofactor oligomerization domain has diverged across evolutionary time, the need for this protein to be oligomeric remains the same.

FIG 7.

Electrostatic analysis of MARV VP35 and paramyxovirus P structures showing the lack of a central basic patch in MARV. Electrostatic surface potentials (kT/e, with k being the Boltzmann constant, T being temperature, and e being the charge of an electron) were calculated for structures of the oligomerization domain of MARV VP35 (PDB code 5TOI) and four paramyxoviruses, Sendai virus (SeV; PDB code 1EZJ), mumps virus (MuV; PDB code 4EIJ), Nipah virus (NiV; PDB code 4N5B), and measles virus (MeV; PDB code 3ZDO) (51). Note that all of the paramyxovirus structures contain a central basic patch that is conserved despite the low sequence conservation among these viruses. MARV VP35 deviates from these structures by lacking a basic patch and instead has an acidic central patch.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant protein expression and purification.

Proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli by using the pET46 vector (Novagen). For crystallization and DSC experiments, MARV (variant Musoke) VP35 residues 60 to 130 were cloned into pET46 with an N-terminal 6×His tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) cleavage site. This construct was designed by using structure predictions from the PSIPRED server (32). For DXMS, MARV VP35 residues 60 to 329 were cloned into pET46 with an N-terminal 6×His tag followed by a TEV cleavage site. EBOV (variant Mayinga) VP35 residues 81 to 340 were similarly cloned with an N-terminal 6×His tag followed by a thrombin cleavage site. Predicted disordered residues upstream of the oligomerization domain of both VP35 proteins were excluded in these constructs to aid in the production of nonaggregated protein.

Plasmids were transformed into Rosetta2 pLysS E. coli cells (Novagen), and overnight starter cultures were used to inoculate 1-liter cultures of Luria broth with 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin. These cultures were grown at 37°C until they reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4 to 0.6, at which time protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Protein expression was carried out at 25°C for 16 to 20 h (overnight), and cells were harvested by centrifugation. Cells expressing MARV VP35 residues 60 to 130 were lysed on ice in 80 ml of a mixture of 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 8), 30 mM imidazole, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 3.125 U/ml Benzonase (Sigma-Aldrich), and 25 μg/ml RNase. These cells were lysed with a Microfluidizer (Microfluidics), and lysates were clarified by centrifugation. MARV VP35 residues 60 to 130 were purified with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) agarose beads (Qiagen) in batch mode. The beads were washed three times with a mixture of 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 8), and 30 mM imidazole and then eluted in a mixture of 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 8), and 250 mM imidazole. The 6×His tag was then removed by treatment with 0.5% (wt/wt) TEV overnight with concurrent dialysis into wash buffer. The cleaved protein was then passed back over Ni-NTA to remove remaining uncleaved protein, cleaved 6×His tags, and the TEV protease. This protein was then concentrated and run over a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Life Sciences) in 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0). Sample purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE analysis and Coomassie staining.

MARV VP35 residues 60 to 329 and EBOV VP35 residues 81 to 340 were purified in a similar manner. Cells were lysed in a mixture of 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 30 mM imidazole, 15% glycerol, 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM PMSF, 3.125 U/ml Benzonase, and 25 μg/ml RNase. Similar batch Ni-NTA purification was carried out with a wash buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 30 mM imidazole, 15% glycerol, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and an elution buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 300 mM imidazole, 15% glycerol, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Next, these proteins were run over a HiTrap Heparin HP 5 ML column (GE Life Sciences) to remove bound RNA. A binding buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 15% glycerol, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol was used, followed by linear gradient elution with an elution buffer consisting of 2 M NaCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 15% glycerol, and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol. EBOV VP35 residues 81 to 340 were further purified by size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 10/300 GL column) in a buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Material for DXMS analysis of MARV VP35 was taken directly from the heparin column elution. Nucleic acid contamination was assessed by analyzing the UV absorption spectra of these purified proteins. Both the MARV and EBOV VP35 proteins were found to be RNA free, with A260/A280 ratios of ≤0.6.

Crystallization and structure determination.

X-ray diffraction data were collected from two different crystal forms of MARV VP35 residues 60 to 130. The first crystal form (space group I2) was grown at room temperature by vapor diffusion from a sitting drop containing 100 mM sodium cacodylate (pH 6.5), 100 mM Mg acetate, and 18% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (MPD) mixed 1:1 with 2.4 mg/ml protein. These crystals were cryoprotected by the addition of 25% ethylene glycol to a solution of mother liquor and then cryocooled in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at Advanced Photon Source beamline 23ID-D. A second crystal form (space group P4222) was grown at room temperature by vapor diffusion from a sitting drop of 0.2 M K/Na tartrate and 40% MPD mixed 1:1 with 13 mg/ml protein. These crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and diffraction data were collected at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource beamline 12-2.

The I2 data set was integrated with XDS (33), scaled, and then merged with AIMLESS (34). This data set displayed strong anisotropy in its diffraction limits. It was therefore submitted to the UCLA-DOE Diffraction Anisotropy Server (35), which yielded an ellipsoidal resolution boundary with limits of 2.9, 3.1, and 2.8 Å along the a*, b*, and c* axes, respectively. The completeness of anisotropic data is naturally reduced by ellipsoidal truncation, but this does not necessitate the exclusion of available high-resolution data for model building and refinement (36). Expecting a tetrameric solution, initial molecular placement (MR) phasing attempts were performed with models based on the tetrameric coiled coils from paramyxovirus phosphoproteins and initial ab initio phasing attempts were performed with tetrameric models generated in Rosetta for use in the CCsolve pipeline (37). Successful ab initio phasing, however, was ultimately performed in Phenix (38) with MR-Rosetta (39) by using the trimeric coiled coil from PDB entry 2YNY as a starting model. As the trimeric nature of the coiled coil in this construct is the major structural conclusion of this study, it seems worth noting that none of the initial attempts with tetrameric models were successful. The successful MR-Rosetta run received monomeric, dimeric, trimeric, tetrameric, and hexameric search models; only the trimeric model led to a successful solution. The 2YNY-derived solution was rebuilt in Coot (40) and refined with Phenix.refine (38) and BUSTER-TNT (41) with final rounds of refinement in Refmac5 (42).

As anisotropy in low-symmetry space groups such as I2 can affect diffraction limits with principal directions not necessarily coincident with individual crystallographic axes (as is assumed by the UCLA server), we chose to revisit the I2 data set with the STARANISO software (43) currently deployed on the Web server at http://staraniso.globalphasing.org. The three main computational steps in STARANISO are as follows. In the first step, an analysis of the anisotropy of decay of the mean intensities (I) is performed, constrained only by the symmetry of the crystal (i.e., here, for space group I2, allowing the two principal directions of anisotropy in the a*,c* plane to be any pair of orthogonal directions in that plane). In the second step, this anisotropy is taken into account in a modification of the TRUNCATE procedure that is applied to small or negative intensities (44). In the third and final step, the decay of the local average of I/σ⟨I⟩ in different directions is analyzed and provides the basis for an anisotropic resolution cutoff. We used here a STARANISO version under development (to be described elsewhere) in which the procedure was extended upstream toward unmerged data in order to prevent the very noisy measurements in the weakly diffracting directions from adversely affecting the scaling and error-model estimation at the final scaling/merging step. Reprocessing of the I2 diffraction images with autoPROC/XDS (45) and applying this unmerged STARANISO protocol produced a best-resolution limit of 2.01 Å and a worst-resolution limit of 4.15 Å at a cutoff level of 1.2 for the local I/σ⟨I⟩ (note that STARANISO does not employ ellipsoidal truncations coincident with the crystal axes). The previously obtained model was then rerefined against these data with BUSTER-TNT (41).

The diffraction data from the P4222 crystal form were initially processed in a manner similar to that used for the I2 crystal form. The data were similarly corrected by the UCLA anisotropy server with ellipsoidal truncation limits of 3.3, 3.3, and 2.4 Å along the a*, b*, and c* axes, respectively. This structure was successfully solved by molecular replacement by using the model from the I2 crystal form, but the refinement statistics remained stubbornly poor, with an Rwork and Rfree values of approximately 0.37 and 0.43, respectively. This led us to suspect an incorrect space group assignment and/or the presence of twinning, but both possibilities were ruled out upon further analysis. We then reprocessed the raw diffraction data with autoPROC/XDS (33, 44), followed by the unmerged STARANISO protocol, which produced a best-resolution limit of 2.19Å and a worst-resolution limit of 4.16 Å at the same cutoff level of 1.2 for the local I/σ⟨I⟩ as used with the I2 form. The MR-derived model was then rerefined against these data with BUSTER-TNT (41). The refinement statistics, although improved (Rwork and Rfree values of approximately 0.316 and 0.333, respectively), were still rather high. Subsequent examination of the map and the refined model revealed a structure with a well-ordered region (average B factor of ∼30 Å2) and a less ordered region (average B factor of ∼90 Å2). The poorly ordered region consists of individual helices that extend from the well-ordered central coiled coil to form extensive but fairly flexible crystal contacts with neighboring protein copies. This is a type of disorder for which no adequate modeling technique is available, which explains the still suboptimal refinement statistics. All data processing and model refinement statistics are shown in Table 1. It should be noted that hydrogens were included during refinement but removed prior to deposition. The structures, although they form anisotropic and challenging data, agree on the trimeric coiled-coil organization.

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameter | Value(s) for MARV VP35 residues 60–135 | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection statistics | ||

| Space group | I121 | P4222 |

| Unit cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 75.69, 35.00, 105.24 | 46.49, 46.49, 310.93 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 105.28, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Resolution range (Å) | 53.02–2.01 (2.12–2.01) | 46.49–2.19 (2.31–2.19) |

| Ellipsoidala resolution (Å) (direction)b | 2.06 (0.98 a* − 0.22 c*) | 3.42 (a*) |

| 2.82 (0.93 b* − 0.38 c*) | 3.42 (b*) | |

| 2.88 (−0.08 a* + 0.05 b* + c*) | 2.22 (c*) | |

| Total no. of reflections (ellipsoidala)c | 17,030 (139) | 76,521 (108) |

| No. of unique reflections (ellipsoidala)c | 7,658 (65) | 6,946 (36) |

| Avg multiplicityc | 2.2 (2.1) | 11.0 (3.0) |

| % Completenessc | 85.0 (47.1) | 85.4 (52.9) |

| % Completeness (ellipsoidala)c,d | 42.1 (2.4) | 34.7 (1.0) |

| I/σ〈I〉 (ellipsoidala)c | 8.3 (1.0) | 12.1 (0.9) |

| Rmeasc,e | 0.18 (1.28) | 0.51 (0.78) |

| Rpimc,f | 0.11 (0.78) | 0.15 (0.42) |

| CC½g | 0.98 (0.12) | 0.99 (0.37) |

| Wilson B factor | 41.6 | 46.9 |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 53.02–2.01 (2.25–2.01) | 42.42–2.19 (2.45–2.19) |

| No. of reflections used | 7,657 (207) | 6,945 (200) |

| Rworkh | 0.24 (0.24) | 0.31 (0.33) |

| Rfreei | 0.27 (0.24) | 0.34 (0.36) |

| No. of atoms | ||

| Protein | 1,417 | 1,662 |

| Water | 26 | 14 |

| Mean B factor (Å2) | ||

| All protein residues | 45.8 | 66.4 |

| Protein residues 59–93 | 39.0 | 37.9 |

| Protein residues 94–128 | 55.6 | 95.1 |

| Water molecules | 39.7 | 18.2 |

| RMSD | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.009 | 0.009 |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.99 | 1.06 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | ||

| Favored regions | 98.2 | 98.5 |

| Allowed regions | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| Outliers | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| MolProbity score | 0.76 | 0.64 |

These statistics are for data that were truncated by STARANISO to remove poorly measured reflections affected by anisotropy.

The resolution limits for three directions in reciprocal space are indicated here. To accomplish this, STARANISO computed an ellipsoid postfitted by least squares to the cutoff surface, removing points where the fit was poor. Note that the cutoff surface is unlikely to be perfectly ellipsoidal, so this is only an estimate.

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell. Note that data collection and refinement statistics have different highest-resolution shells.

The anisotropic completeness was obtained by least squares fitting an ellipsoid to the reciprocal lattice points at the cutoff surface defined by a local mean I/σ〈I〉 threshold of 1.2, rejecting outliers in the fit due to spurious deviations (including any cusp), and calculating the fraction of observed data lying inside the ellipsoid so defined. Note that the cutoff surface is unlikely to be perfectly ellipsoidal, so this is only an estimate.

Rmeas = Σhkl{N(hkl)/[N(hkl) − 1]}1/2 × Σi|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/Σhkl Σi Ii(hkl).

Rpim = Σhkl{1/[N(hkl) − 1]}1/2 × Σi|Ii(hkl) − 〈I(hkl)〉|/Σhkl Σi Ii(hkl).

CC1/2 = Σ(x − 〈x〉)(y − 〈x〉)/[Σ(x − 〈x〉)2Σ(y − 〈y〉)2]1/2.

Rwork = (Σhkl||Fobs| − k |Fcalc||)/(Σhkl |Fobs|).

Rfree is the same as Rwork with 5% of reflections chosen at random and omitted from refinement.

SEC/MALS.

Purified EBOV VP35 residues 80 to 340 was separated on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL gel filtration column (GE Life Sciences) pre-equilibrated with buffer (300 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) coupled in line with a miniDAWN TREOS followed by an Optilab T-rEX refractometer (Wyatt Technologies). Data processing and absolute molecular mass calculations were performed with ASTRA software (Wyatt Technologies).

DSC.

Thermal denaturation was probed with a MicroCal VP-Capillary differential scanning calorimeter (Malvern Instruments). MARV VP35 residues 60 to 130 were concentrated to 2 mg/ml in 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM Tris (pH 8) for thermal denaturation measurements. After the protein sample was loaded into the cell, thermal denaturation was probed at a scan rate of 90°C/h from 25 to 130°C. Buffer correction, normalization, and baseline subtraction procedures were applied before the data were analyzed using Origin 7.0 software. The data were fitted by using a two-state model.

DXMS.

Prior to hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiments, the optimal concentration of guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl) for protein fragmentation with pepsin was determined as previously described (46–48). Final GuHCl concentrations of 1.0 and 2.0 M were found to produce the best fragmentation maps of EBOV VP35 residues 81 to 340 and MARV VP35 residues 60 to 329, respectively. Functional deuteration studies were initiated by diluting 3 μl of a stock protein solution (EBOV VP35 residues 81 to 340 at 1.18 mg/ml or MARV VP35 residues 60 to 329 at 1.78 mg/ml) with 9 μl of D2O buffer (8.3 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl in D2O, pDread 7.2) at 0°C. At 10, 100, and 1,000 s, the exchange reaction was quenched by adding 18 μl of ice-cold optimal quench solution (1.6 M GuHCl for EBOV or 3.2 M GuHCl for MARV, 16.6% glycerol, 0.8% formic acid). Quenched samples were then immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C. The equilibrium-deuterated back-exchange control samples were also prepared by diluting protein with D2O buffer containing 0.8% formic acid and incubating them overnight at 25°C. The frozen samples were then thawed at 4°C and passed over an in-house immobilized pepsin column (PROS AL-20; 1 by 20 mm) at a flow rate of 20 μl/min, and digested peptides were collected on a C18 trap for desalting and separated by a Magic C18 AQ reverse-phase column (Michrom; 0.2 by 50 mm) with a linear gradient of 8 to 48% solvent B (80% acetonitrile and 0.01% trifluoroacetic acid) over 30 min. MS analysis was performed with an Orbitrap Elite Mass Spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific), with a capillary temperature of 200°C. Data were acquired in both data-dependent tandem mass spectrometry mode and MS1 profile mode, and the data were analyzed by Proteome Discoverer software and DXMS explorer (Sierra Analytics Inc., Modesto, CA).

Accession number(s).

The coordinates and structure factors for the MARV VP35 oligomerization domain structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/) and assigned PDB codes 5TOH for the I2 structure and 5TOI for the P4222 structure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the beamline staff of GM/CA at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) for the use of 23ID-D. GM/CA at the APS has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) (AGM-12006). This research used resources of the APS, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by the Argonne National Laboratory under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. We also thank the BeamlineXpress program at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource for facilitating data collection time on beamline 12-2. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. DOE Office of Science Office of Basic Energy Sciences under contract DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the NIGMS, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (including P41GM103393). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS or the NIH. J.F.B. was supported by NIH training grant T32 AI007606 to The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) Department of Immunology and Microbial Science, the Delia and Donald Baxter Fellowship program, and the Roche/Achievement Rewards for College Scientists (ARCS) program. E.O.S. is supported by an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, and NIH/NIAID grant R01 AI118016. Additional funding for S.L. was provided by NIH grants 1U19 AI117905, R01 GM020501, and R01 AI101436. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

We thank Robyn Stanfield at TSRI and Kay Diederichs at the University of Constance for advice on structure refinement. We also thank Arthur Olson for discussions about the asymmetric trimer and intimate crystal contacts observed in these structures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brauburger K, Hume AJ, Mühlberger E, Olejnik J. 2012. Forty-five years of Marburg virus research. Viruses 4:1878–1927. doi: 10.3390/v4101878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Messaoudi I, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. 2015. Filovirus pathogenesis and immune evasion: insights from Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Nat Rev Microbiol 13:663–676. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott LH, Kiley MP, McCormick JB. 1985. Descriptive analysis of Ebola virus proteins. Virology 147:169–176. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mühlberger E, Lotfering B, Klenk HD, Becker S. 1998. Three of the four nucleocapsid proteins of Marburg virus, NP, VP35, and L, are sufficient to mediate replication and transcription of Marburg virus-specific monocistronic minigenomes. J Virol 72:8756–8764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivanov I, Yabukarski F, Ruigrok RWH, Jamin M. 2011. Structural insights into the rhabdovirus transcription/replication complex. Virus Res 162:126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mühlberger E. 2007. Filovirus replication and transcription. Future Virol 2:205–215. doi: 10.2217/17460794.2.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ortín J, Martin-Benito J. 2015. The RNA synthesis machinery of negative-stranded RNA viruses. Virology 479-480:532–544. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker S, Rinne C, Hofsass U, Klenk HD, Mühlberger E. 1998. Interactions of Marburg virus nucleocapsid proteins. Virology 249:406–417. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mühlberger E, Weik M, Volchkov VE, Klenk HD, Becker S. 1999. Comparison of the transcription and replication strategies of Marburg virus and Ebola virus by using artificial replication systems. J Virol 73:2333–2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirchdoerfer RN, Abelson DM, Li S, Wood MR, Saphire EO. 2015. Assembly of the Ebola virus nucleoprotein from a chaperoned VP35 complex. Cell Rep 12:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung DW, Borek D, Luthra P, Binning JM, Anantpadma M, Liu G, Harvey IB, Su Z, Endlich-Frazier A, Pan J, Shabman RS, Chiu W, Davey RA, Otwinowski Z, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2015. An intrinsically disordered peptide from Ebola virus VP35 controls viral RNA synthesis by modulating nucleoprotein-RNA interactions. Cell Rep 11:376–389. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prins KC, Binning JM, Shabman RS, Leung DW, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. 2010. Basic residues within the ebolavirus VP35 protein are required for its viral polymerase cofactor function. J Virol 84:10581–10591. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00925-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cárdenas WB, Loo YM, Gale M Jr, Hartman AL, Kimberlin CR, Martinez-Sobrido L, Saphire EO, Basler CF. 2006. Ebola virus VP35 protein binds double-stranded RNA and inhibits α/β interferon production induced by RIG-I signaling. J Virol 80:5168–5178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02199-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bale S, Julien JP, Bornholdt ZA, Krois AS, Wilson IA, Saphire EO. 2013. Ebolavirus VP35 coats the backbone of double-stranded RNA for interferon antagonism. J Virol 87:10385–10388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01452-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramanan P, Edwards MR, Shabman RS, Leung DW, Endlich-Frazier AC, Borek DM, Otwinowski Z, Liu G, Huh J, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2012. Structural basis for Marburg virus VP35-mediated immune evasion mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:20661–20666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213559109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bale S, Julien JP, Bornholdt ZA, Kimberlin CR, Halfmann P, Zandonatti MA, Kunert J, Kroon GJ, Kawaoka Y, MacRae IJ, Wilson IA, Saphire EO. 2012. Marburg virus VP35 can both fully coat the backbone and cap the ends of dsRNA for interferon antagonism. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002916. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung DW, Shabman RS, Farahbakhsh M, Prins KC, Borek DM, Wang T, Mühlberger E, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2010. Structural and functional characterization of Reston Ebola virus VP35 interferon inhibitory domain. J Mol Biol 399:347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prins KC, Delpeut S, Leung DW, Reynard O, Volchkova VA, Reid SP, Ramanan P, Cárdenas WB, Amarasinghe GK, Volchkov VE, Basler CF. 2010. Mutations abrogating VP35 interaction with double-stranded RNA render Ebola virus avirulent in guinea pigs. J Virol 84:3004–3015. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02459-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung DW, Prins KC, Borek DM, Farahbakhsh M, Tufariello JM, Ramanan P, Nix JC, Helgeson LA, Otwinowski Z, Honzatko RB, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. 2010. Structural basis for dsRNA recognition and interferon antagonism by Ebola VP35. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17:165–172. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimberlin CR, Bornholdt ZA, Li S, Woods VL Jr, MacRae IJ, Saphire EO. 2010. Ebolavirus VP35 uses a bimodal strategy to bind dsRNA for innate immune suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:314–319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910547107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung DW, Ginder ND, Fulton DB, Nix J, Basler CF, Honzatko RB, Amarasinghe GK. 2009. Structure of the Ebola VP35 interferon inhibitory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:411–416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807854106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards MR, Liu G, Mire CE, Sureshchandra S, Luthra P, Yen B, Shabman RS, Leung DW, Messaoudi I, Geisbert TW, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. 2016. Differential regulation of interferon responses by Ebola and Marburg virus VP35 proteins. Cell Rep 14:1632–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Möller P, Pariente N, Klenk HD, Becker S. 2005. Homo-oligomerization of Marburgvirus VP35 is essential for its function in replication and transcription. J Virol 79:14876–14886. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14876-14886.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luthra P, Jordan DS, Leung DW, Amarasinghe GK, Basler CF. 2015. Ebola virus VP35 interaction with dynein LC8 regulates viral RNA synthesis. J Virol 89:5148–5153. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03652-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grigoryan G, Degrado WF. 2011. Probing designability via a generalized model of helical bundle geometry. J Mol Biol 405:1079–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walshaw J, Woolfson DN. 2001. Socket: a program for identifying and analysing coiled-coil motifs within protein structures. J Mol Biol 307:1427–1450. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. 1991. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252:1162–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruhn JF, Barnett KC, Bibby J, Thomas JM, Keegan RM, Rigden DJ, Bornholdt ZA, Saphire EO. 2014. Crystal structure of the Nipah virus phosphoprotein tetramerization domain. J Virol 88:758–762. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02294-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Communie G, Crepin T, Maurin D, Jensen MR, Blackledge M, Ruigrok RW. 2013. Structure of the tetramerization domain of measles virus phosphoprotein. J Virol 87:7166–7169. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00487-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowman MC, Smallwood S, Moyer SA. 1999. Dissection of individual functions of the Sendai virus phosphoprotein in transcription. J Virol 73:6474–6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickar A, Elson A, Yang Y, Xu P, Luo M, He B. 2015. Oligomerization of mumps virus phosphoprotein. J Virol 89:11002–11010. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01719-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchan DW, Minneci F, Nugent TC, Bryson K, Jones DT. 2013. Scalable web services for the PSIPRED Protein Analysis Workbench. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W349–W357. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabsch W. 2010. Integration, scaling, space-group assignment and post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66(Pt 2):133–144. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans PR, Murshudov GN. 2013. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69:1204–1214. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strong M, Sawaya MR, Wang S, Phillips M, Cascio D, Eisenberg D. 2006. Toward the structural genomics of complexes: crystal structure of a PE/PPE protein complex from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:8060–8065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602606103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawaya MR. 2014. Methods to refine macromolecular structures in cases of severe diffraction anisotropy. Methods Mol Biol 1091:205–214. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-691-7_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rämisch S, Lizatovic R, Andre I. 2015. Automated de novo phasing and model building of coiled-coil proteins. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 71(Pt 3):606–614. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714028247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terwilliger TC, Dimaio F, Read RJ, Baker D, Bunkoczi G, Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Afonine PV, Echols N. 2012. phenix.mr_rosetta: molecular replacement and model rebuilding with Phenix and Rosetta. J Struct Funct Genomics 13:81–90. doi: 10.1007/s10969-012-9129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanc E, Roversi P, Vonrhein C, Flensburg C, Lea SM, Bricogne G. 2004. Refinement of severely incomplete structures with maximum likelihood in BUSTER-TNT. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:2210–2221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904016427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. 2011. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tickle IJ, Bricogne G, Flensburg C, Keller P, Paciorek W, Sharff A, Vonrhein C. 2016. STARANISO. Global Phasing Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom: http://staraniso.globalphasing.org/cgi-bin/staraniso.cgi. [Google Scholar]

- 44.French S, Wilson K. 1978. On the treatment of negative intensity observations. Acta Crystallogr A 34:517–525. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vonrhein C, Flensburg C, Keller P, Sharff A, Smart O, Paciorek W, Womack T, Bricogne G. 2011. Data processing and analysis with the autoPROC toolbox. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67:293–302. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911007773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li S, Tsalkova T, White MA, Mei FC, Liu T, Wang D, Woods VL Jr, Cheng X. 2011. Mechanism of intracellular cAMP sensor Epac2 activation: cAMP-induced conformational changes identified by amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (DXMS). J Biol Chem 286:17889–17897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.224535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bale S, Liu T, Li S, Wang Y, Abelson D, Fusco M, Woods VL Jr, Saphire EO. 2011. Ebola virus glycoprotein needs an additional trigger, beyond proteolytic priming for membrane fusion. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5:e1395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olal D, Dick A, Woods VL Jr, Liu T, Li S, Devignot S, Weber F, Saphire EO, Daumke O. 2014. Structural insights into RNA encapsidation and helical assembly of the Toscana virus nucleoprotein. Nucleic Acids Res 42:6025–6037. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stuart DI, Levine M, Muirhead H, Stammers DK. 1979. Crystal structure of cat muscle pyruvate kinase at a resolution of 2.6 Å. J Mol Biol 134:109–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90416-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Retief JD. 2000. Phylogenetic analysis using PHYLIP. Methods Mol Biol 132:243–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Unni S, Huang Y, Hanson RM, Tobias M, Krishnan S, Li WW, Nielsen JE, Baker NA. 2011. Web servers and services for electrostatics calculations with APBS and PDB2PQR. J Comput Chem 32:1488–1491. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]