Abstract

Background

There is an ongoing debate about the value of (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy in high‐ and intermediate‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck.

Methods

All records of patients older than 16 years diagnosed with osteosarcoma of the head and neck in the Netherlands between 1993 and 2013 were reviewed.

Results

We identified a total of 77 patients with an osteosarcoma of the head and neck; the 5‐year overall survival (OS) was 55%. In 50 patients with surgically resected high‐ or intermediate‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck younger than 75 years, univariate and multivariable analysis, adjusting for age and resection margins, showed that patients who had not received chemotherapy had a significantly higher risk of local recurrence (hazard ratio [HR] = 3.78 and 3.66, respectively).

Conclusion

In patients younger than 75 years of age with surgically resected high‐ and intermediate‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck, treatment with (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy resulted in a significantly smaller risk of local recurrence. Therefore, we suggest (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy in patients amenable to chemotherapy. © 2016 The Authors Head & Neck Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Head Neck 39: 140–146, 2017

Keywords: osteosarcoma, head and neck neoplasms, chemotherapy, (neo‐)adjuvant, mandible, maxilla

INTRODUCTION

Osteosarcoma is an aggressive bone tumor characterized by the formation of osteoid by malignant osteoblasts.1 It most commonly occurs in the extremities and mainly effects teenagers and young adults. Osteosarcoma of the head and neck accounts for approximately 6% of all osteosarcomas.2

The current treatment for extremity osteosarcomas is neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. One of the main aims of chemotherapy is early treatment of occult distant metastases. Since the introduction of chemotherapy, the overall survival (OS) improved dramatically with a 5‐year OS of about 60% to 70% currently.3 Osteosarcoma of the head and neck behaves differently from extremity osteosarcoma. First, the median age is at least 2 decades higher.4 Second, although patients with extremity osteosarcoma have a very high risk of metastatic disease of the lungs (44% to 49%),5 pulmonary metastases are less common in patients with osteosarcoma of the head and neck (4% to 43%).6, 7 Furthermore, local recurrences predominate in osteosarcoma of the head and neck with a reported incidence of 17% to 70%2, 8 compared with 5% to 7% in extremity osteosarcoma.5 This could be attributed to the difficulty to obtain tumor‐free margins by surgery in the head and neck region.

In view of these differences, there is an ongoing debate about the value of (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment for osteosarcoma of the head and neck. The opponents of chemotherapy argue that, because pulmonary metastases only occasionally develop, chemotherapy has no role in the primary treatment of osteosarcoma of the head and neck. Because of the rarity of the disease, only small retrospective case series have been described.7, 9, 10 The single meta‐analysis (173 patients) and systematic review (201 patients) show conflicting results about the use of (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy.4, 11

The purpose of this retrospective study — with a review of each individual medical report — was to describe the treatment and outcomes of patients who were diagnosed with osteosarcoma of the head and neck in The Netherlands over the last 2 decades, with special attention to the role of (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in patients diagnosed with osteosarcoma of the head and neck from 1993 until July 2013 within the Dutch Head and Neck Society.

Local pathologists of the 8 participating head and neck centers were asked to provide a search with the term ‘osteosarcoma” in combination with head and neck locations, such as “jaw,” “mandible,” “maxilla,” “larynx,” or “skull.” Patients older than 16 years of age with a histopathological proven diagnosis of osteosarcoma and with a primary location in the head and neck region were included. In the Netherlands, there is a special multidisciplinary expert team available for reviewing cases with bone tumors (Netherlands Committee on Bone Tumors [NCBT]). For all patients in this study, histological evaluation was (also) performed and confirmed by either the NCBT or an experienced pathologist's part of the NCBT in their affiliated hospitals. For all cases in which histological grade was either intermediate or not reported, hematoxylin‐eosin stained slides were retrieved from the archives and revised by 2 experienced musculoskeletal pathologists (J.B. and U.F.).

All medical records were reviewed for patients' characteristics, such as age, sex, and medical history, as well as information concerning diagnosis (location, grading, and subtype), treatment (surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy), occurrence of local recurrence or distant metastases, and survival.

Data analysis

Resection margins were classified by pathological assessment and categorized in 3 categories; intralesional, marginal, or wide, according to Enneking et al.12 Intralesional and unknown resection margins were considered incomplete, whereas marginal and wide resection margins were considered complete. OS was defined as time (in months) from date of diagnosis until date of death of any cause; patients alive at last known follow‐up date were censored. Disease‐free survival (DFS) was defined as time (in months) from surgery until the date of the first event (local recurrence, distant metastases, or death), patients alive without disease at last known follow‐up date were censored. Local recurrence and distant metastases were measured by radiological evaluation and preferably confirmed by pathological assessment. Patients without surgical resection were not included in the DFS calculations or survival figures. Local recurrence‐free interval (LRFI) was defined as time (in months) from surgery until the occurrence of a local recurrence. Patients without a local recurrence were censored at the date of death or last known follow‐up date.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan–Meier method was performed to create survival figures. Log‐rank tests were used to compare the survival curves between groups. The adjustment of the HR for chemotherapy for confounders was restricted to age and resection margins in a Cox regression model because of the limited number of events. The analysis of the effect of chemotherapy on OS, DFS, and LFRI was limited to surgical‐resected patients with high or intermediate grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck and <75 years of age, because (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy for elderly patients is not considered in this setting. The size of the effect of chemotherapy was defined as the ratio between the hazard of the event in the patients who were not treated with chemotherapy and the hazard of the event in the patients treated with chemotherapy. It was calculated using a Cox proportional hazards regression model. HRs are reported with 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A p value of < .05 was considered to be significant. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 20.

RESULTS

Patients' characteristics and treatment of the 77 patients with osteosarcoma of the head and neck

A total of 77 patients with osteosarcoma of the head and neck were identified. Thirty‐six patients (47%) were men and the median age at diagnosis was 46 years (range, 16–95 years). Patients' characteristics are summarized in Table 1. A total of 25 patients (33%) had a previous malignancy. The median age at the time of diagnosis of this first nonosteosarcoma of the head and neck primary tumor was 30 years (range, 1–77 years). Seven patients had multiple primary malignancies. One case of Li‐Fraumeni syndrome was identified. Four patients were treated for retinoblastoma in childhood. Twenty‐two patients (29%) previously received radiotherapy, of which 19 (86%) were in the head and neck region. The median age at the time of the previous radiotherapy of the head and neck was 30 years (range, 1–77 years). The median time between the prior radiotherapy and the presentation of the osteosarcoma of the head and neck was 16 years (range, 7–60 years). The most common tumor location was the jaw (73%; Table 1). Fifty‐eight tumors (75%) were classified as high‐grade, 6 (8%) as intermediate‐grade, and 11 (14%) as low‐grade osteosarcoma. At the time of diagnosis, none of the patients had involvement of the lymph nodes in the neck and only 1 patient presented with pulmonary metastases.

Table 1.

Patients' and tumor characteristics for all patients (n = 77) and for patients with high‐ and intermediate‐grade resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck, age <75 years according to treatment with (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy.

| High‐ and intermediate‐grade resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck, age <75 y | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

All patients No. of patients = 77 No. of patients (%) |

Chemotherapy No. of patients = 29 No. of patients (%) |

No chemotherapy No. of patients = 21 No. of patients (%) |

|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 36 (47) | 16 (55) | 10 (48) |

| Female | 41 (53) | 13 (45) | 11 (52) |

| Age, y | |||

| Median (range) | 46 (16–95) | 41 (16–74) | 57 (19–75) |

| Tumor site | |||

| Maxilla | 24 (31) | 8 (28) | 5 (24) |

| Mandible | 32 (42) | 11 (38) | 11 (52) |

| Paranasal sinuses | 7 (9) | 4 (14) | 0 |

| Skull bone | 4 (5) | 2 (7) | 2 (10) |

| Skull base | 2 (3) | 0 | 1 (5) |

| Orbital bone | 3 (4) | 3 (10) | 0 |

| Ethmoid bone | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 3 (4) | 1 (3) | 2 (10) |

| Osteosarcoma subtype | |||

| Conventional | 51 (66) | 13 (45) | 11 (52) |

| Chondroblastic | 11 (14) | 7 (24) | 6 (29) |

| Osteoblastic | 6 (8) | 6 (21) | 2 (10) |

| Sclerosing | 2 (3) | 2 (7) | 0 |

| Fibroblastic | 7 (9) | 1 (3) | 2 (10) |

| Grade | |||

| Low | 11 (14) | 0 | 0 |

| Intermediate | 6 (8) | 3 (10) | 3 (14) |

| High | 58 (75) | 26 (90) | 18 (86) |

| Unknown | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Resection margins | |||

| Complete, no. (%) | 38 (49) | 13 (45) | 10 (48) |

| Incomplete, no. (%) | 32 (42) | 16 (55) | 11 (52) |

| No surgery, no. (%) | 7 (9) | ||

| Median follow‐up time in mo (range) | 34 (0–223) | 30 (4–181) | 44 (1–223) |

| Local recurrence | 14 | 2 | 8 |

| Local recurrence and distant metastases | 7 | 1 | 5 |

| Distant metastases | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Deaths | 35 | 8 | 13 |

Patients were treated according to the local policy of the multidisciplinary head and neck cancer working group. Seventy patients (91%) underwent surgical resection. In total, 17 patients (22%) received radiotherapy. The median dose was 58 Gy (range, 8–70 Gy). Fourteen patients received postoperative radiotherapy because of irradical resection, 2 other patients received radiotherapy as single treatment, and 1 patient received radiotherapy because of tumor bleeding.

The 5‐year OS was 55% for all 77 patients.

Low grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck

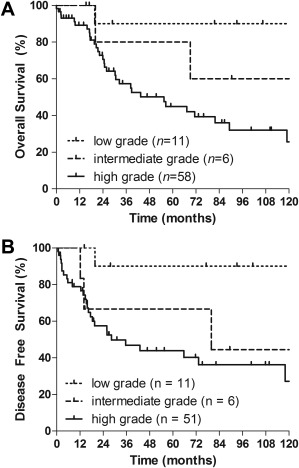

All patients with low‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck (n = 11) underwent surgical resection. Only 1 patient (9%) received postoperative radiotherapy because of an intralesional resection. None of them were treated with chemotherapy. After a median follow‐up time of 106 months (range, 15–198 months), none of the patients developed a local recurrence or distant metastases. One patient had a second primary malignancy. One patient died without evidence of disease. The 5‐year OS and DFS were both 90% (Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Overall survival estimation stratified by the differentiation grade of the tumor of all patients (log‐rank p = .023). Two patients were left out of this figure because of an unknown differentiation grade. (B) Disease‐free survival estimation stratified by the differentiation grade of the tumor of resected patients (log‐rank p = .029). Nine patients were left out of this figure; 2 patients because of an unknown differentiation grade, and 7 patients for not having surgery, and, thus, not being disease‐free at any time.

High‐ or intermediate‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck

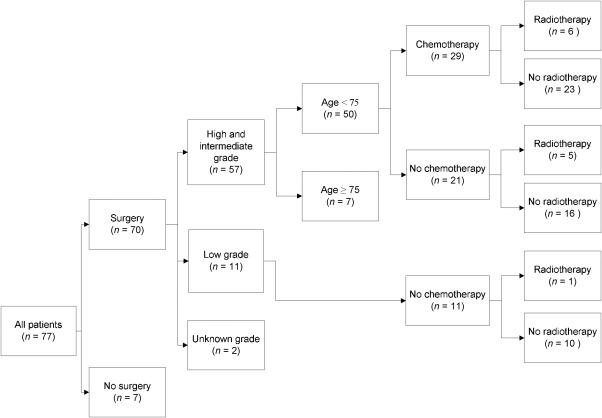

Sixty‐four patients had high‐ or intermediate‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck. Fourteen patients were excluded from further analysis for the effect of chemotherapy because of their age (75 years or older) or because no surgical resection was performed. The characteristics of the remaining 50 patients are displayed in Table 1 according to treatment with (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy. Treatment characteristics are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Treatment algorithm for all patients with special notice to patients with high‐ or intermediate‐grade resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck, aged <75 years.

Treatment

A total of 29 patients (58%) received chemotherapy, of whom 12 patients (41%) received neoadjuvant, 8 (28%) received adjuvant, and 9 (31%) received both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy. The most frequently used chemotherapy consisted of a combination of cisplatin and doxorubicin. The median number of cycles of chemotherapy was 4 (range, 1–6 cycles).

After neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n = 21), the resection specimens showed >90% tumor necrosis in 5 patients (24%). Forty‐five percent of chemotherapy‐treated patients had a complete resection versus 48% in patients who did not receive chemotherapy (Table 1). Six patients (21%) treated with chemotherapy and 5 patients (24%) not treated with chemotherapy received radiotherapy (Figure 2).

Recurrent disease and survival

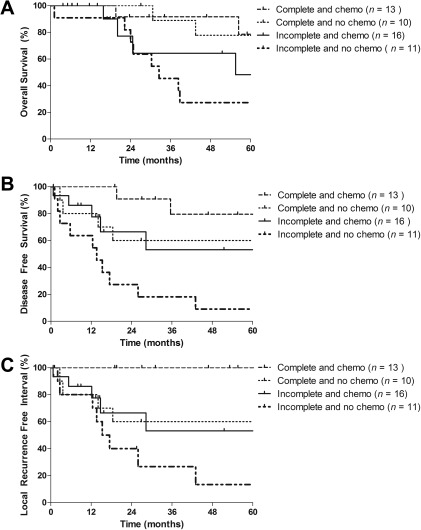

The numbers of local recurrences and/or distant metastases in patients with a high‐ or intermediate‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck and aged <75 years are shown in Table 1. After a median follow‐up time of 30 months (range, 4–181 months) and 44 (range, 1–223 months), respectively, 8 patients in the chemotherapy treated and 13 patients in the non‐chemotherapy treated group had died. The 5‐year OS was 66% versus 51% in the chemotherapy versus non‐chemotherapy treated patients, respectively, and the respective 5‐year DFS was 67% versus 33%.

Prognostic factors

Univariate analysis

In univariate analyses, surgical resected patients with a high‐ or intermediate‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck, aged <75 years, and not treated with (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy had a significantly worse DFS (HR = 2.50; 95% CI = 1.09–5.71; p = .030) and higher risk of local recurrence (HR = 3.78; 95% CI = 1.35–10.62; p = .012). There was no significant difference in OS (HR = 1.60; 95% CI = 0.66–3.86; p = .30). Patients with an incomplete resection had a significantly worse OS (HR = 2.75; 95% CI = 1.13–6.73; p = .026), DFS (HR = 2.56; 95% CI = 1.10–5.93; p = .029), and higher risk of local recurrence (HR = 3.66; 95% CI = 1.29–10.38; p = .015). Male sex, radiotherapy, and age were not significant prognostic factors in a univariate analysis for OS, DFS, and LRFI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariable analysis for high‐ and intermediate‐grade resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck, aged <75 years, for overall survival, disease‐free survival, and local recurrence‐free interval.

| High‐ + intermediate‐grade, resected patients, age <75 y |

OS HR (95% CI) |

p value |

DFS HR (95% CI) |

p value |

LRFI HR (95% CI) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis (No. of patients = 50) | ||||||

| Age, y | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | .072 | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | .16 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | .49 |

| Incomplete resection | 2.75 (1.13–6.73) | .026 | 2.56 (1.10–5.93) | .029 | 3.66 (1.29–10.38) | .015 |

| No chemotherapy | 1.60 (0.66–3.86) | .30 | 2.50 (1.09–5.71) | .030 | 3.78 (1.35–10.62) | .012 |

| Male sex | 0.83 (0.34–2.00) | .67 | 0.88 (0.39–1.99) | .76 | 1.27 (0.50–3.24) | .62 |

| Radiotherapy | 1.76 (0.64–4.89) | .28 | 1.70 (0.66–4.36) | .27 | 1.68 (0.59–4.74) | .33 |

| Multivariable analysis (No. of patients = 50) | ||||||

| Age, y | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | .03 | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | .23 | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | .87 |

| Incomplete resection | 3.72 (1.43–9.69) | .007 | 3.10 (1.28–7.55) | .013 | 3.72 (1.28–10.79) | .016 |

| No chemotherapy | 1.06 (0.40–2.77) | .91 | 2.10 (0.85–5.18) | .11 | 3.66 (1.21–11.08) | .022 |

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; DFS, disease‐free survival; LRFI, local recurrence‐free interval.

Multivariable analysis

In a multivariable analysis, surgical resected patients with a high‐ or intermediate‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck, aged <75 years, and not treated with (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy had a significantly higher risk of a local recurrence when adjusted for age and resection margins (HR = 3.66; 95% CI = 1.21–11.08; p = .022). Chemotherapy had no significant impact on OS and DFS.

Patients with an incomplete surgical resection had a significant worse OS (HR = 3.72; 95% CI = 1.43–9.69; p = .007), DFS (HR = 3.10; 95% CI = 1.28–7.55; p = .013), and higher risk of local recurrence (HR = 3.72; 95% CI = 1.28–10.79; p = .016) when adjusted for age and chemotherapy (Table 2).

In a univariate analysis, there was an indication for age as a prognostic factor for OS (p = .072). In a multivariable analysis, age actually was a significant prognostic factor for OS (HR = 1.03; 95% CI = 1.00–1.06; p = .03), but not for DFS and LRFI (Table 2).

OS, DFS, and LRFI for patients according to both chemotherapy and resection margins are shown in Figure 3A to 3C. Figure 3C gives the probability of local recurrence in the absence of the competing risk of death.

Figure 3.

(A) Overall survival estimation for high‐ and intermediate‐grade resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck aged <75 years according to both resection margins and (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy (log‐rank p = .036). (B) Disease‐free survival estimation for high‐ and intermediate‐grade resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck aged <75 years according to both resection margins and (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy (log‐rank p = .003). (C) Local recurrence‐free interval estimation for high‐ and intermediate‐grade resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck aged <75 years according to both resection margins and (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy (log‐rank p = .003).

DISCUSSION

Because of the rarity of OSHN, conflicting results of in general small case series, and the lack of clinical studies, the role of chemotherapy in the treatment of patients with OSHN is a continuous subject for debate. We performed one of the largest case studies so far, including data of treatment of all individual patients and showed that patients aged <75 years with high or intermediate‐grade resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck and treated with (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy had a significant smaller risk on local recurrence in univariate and multivariable analyses when adjusting for age and resection margins. Although this effect was not shown for OS and DFS in a multivariable analysis, this observation has important implications. A local recurrence in the head and neck region, in general, causes serious problems with hardly any curative options. Often, this palliative phase is dominated by (neuropathic) pain, speech impairment, and swallowing dysfunction with a strongly negative impact on the quality of life. Accordingly, prolonged LRFI is considered beneficial for the patient. We showed that this could be achieved by administration of (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy and, although we cannot present toxicity data of the chemotherapy given, our results suggest that the use of (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy is an advantage for patients aged younger than 75 years with high‐ or intermediate‐grade surgically resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck.

Patients with intermediate‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck were analyzed together with high‐grade patients, because the natural course of disease is more in accordance with high‐grade than with low‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck. This is shown by our own data and by a French cohort of patients with mandibular osteosarcoma.13 Patients with low‐grade disease were excluded because of the less aggressive natural course of disease. Based on expected toxicity, chemotherapy is not considered for patients above a certain age. Therefore, only patients younger than 75 years with surgical resections were included for univariate and multivariable analysis.

As far as we know, this is the first report of an effect of chemotherapy on LRFI in osteosarcoma of the head and neck. A systematic review of 201 patients reported an OS and DFS benefit for chemotherapy‐treated patients in those with a complete as well an incomplete resection.4 An effect of chemotherapy on LRFI was not reported in this study. A recently published large French cohort of 111 patients with mandibular osteosarcomas, in both children and adults, showed improved DFS (HR = 2.87; 95% CI = 1.10–7.51; p = .025) and metastatic‐free survival (HR = 4.40; 95% CI = 1.46–13.28; p = .004) by (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy, but no effect on OS.13 These results are in line with our findings of an HR of 2.50 (95% CI = 1.09–5.71; p = .030) of chemotherapy on DFS in a univariate analysis, and no effect on OS. A meta‐analysis of 173 patients did not find a survival benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy; however, resection margins were not taken into account.11 The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database for 541 patients with osteosarcoma of the jaw did not provide data on chemotherapy.14

Patients with low‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck have a less aggressive natural course of disease. This was also observed in our group in which none of the patients developed local recurrences or distant metastases and long‐term OS and DFS were both 90%. Therefore, these findings do not support the use of (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with low‐grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck.

A history of cancer and/or irradiation is a well‐recognized risk factor for development of osteosarcoma of the head and neck.13 We report a high incidence of previous malignancy (33%). Whether this is due to germ line susceptibility and/or external factors remains to be explored. We had a high percentage of patients (25%) previously irradiated in the head and neck region, which was even more frequent than the reported 15% for mandibular osteosarcomas.13

One of the limitations of this study was its retrospective design. Although care for osteosarcoma of the head and neck is centralized in the 8 centers of the Dutch Head and Neck Society, heterogeneity exists between the centers. However, a multidisciplinary approach is always used in all centers. Because of the small number of patients, only a limited number of events occurred and, thus, only a limited number of prognostic factors could be included in the multivariable analysis. The presence of comorbidity was not taken into account.

One of the strong points of this series was the individual base of data collection, studying all patients' medical records. Histological classification was confirmed by either the NCBT or pathologists from the NCBT in their affiliated hospitals. Furthermore, we have a long median follow‐up time, which leads to meaningful clinical observations.

CONCLUSION

Patients with high‐ and intermediate‐grade surgical resected osteosarcoma of the head and neck aged younger than 75 years treated with (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy had significantly smaller risk on local recurrence in both univariate and multivariable analyses. Despite the limitations of this study, we suggest the use of (neo‐)adjuvant chemotherapy in high‐ or intermediate‐grade tumors in patients younger than 75 years, irrespective of resection margins, because of the large impact on quality of life in case of a local recurrence.

This work was presented at the poster presentation of the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, May 30 to June 3, 2014.

REFERENCES

- 1. Slootweg PJ, Müller H. Osteosarcoma of the jaw bones. Analysis of 18 cases. J Maxillofac Surg 1985;13:158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clark JL, Unni KK, Dahlin DC, Devine KD. Osteosarcoma of the jaw. Cancer 1983;51:2311–2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anninga JK, Gelderblom H, Fiocco M, et al. Chemotherapeutic adjuvant treatment for osteosarcoma: where do we stand? Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2431–2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smeele LE, Kostense PJ, van der Waal I, Snow GB. Effect of chemotherapy on survival of craniofacial osteosarcoma: a systematic review of 201 patients. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:363–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Whelan JS, Jinks RC, McTiernan A, et al. Survival from high‐grade localised extremity osteosarcoma: combined results and prognostic factors from three European Osteosarcoma Intergroup randomised controlled trials. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1607–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garrington GE, Scofield HH, Cornyn J, Hooker SP. Osteosarcoma of the jaws. Analysis of 56 cases. Cancer 1967;20:377–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laskar S, Basu A, Muckaden MA, et al. Osteosarcoma of the head and neck region: lessons learned from a single‐institution experience of 50 patients. Head Neck 2008;30:1020–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ketabchi A, Kalavrezos N, Newman L. Sarcomas of the head and neck: a 10‐year retrospective of 25 patients to evaluate treatment modalities, function and survival. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011;49:116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Es RJ, Keus RB, van der Waal I, Koole R, Vermey A. Osteosarcoma of the jaw bones. Long‐term follow up of 48 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997;26:191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mücke T, Mitchell DA, Tannapfel A, Wolff KD, Loeffelbein DJ, Kanatas A. Effect of neoadjuvant treatment in the management of osteosarcomas of the head and neck. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2014;140:127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kassir RR, Rassekh CH, Kinsella JB, Segas J, Carrau RL, Hokanson JA. Osteosarcoma of the head and neck: meta‐analysis of nonrandomized studies. Laryngoscope 1997;107:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Enneking WF, Spanier SS, Goodman MA. A system for the surgical staging of musculoskeletal sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1980;153:106–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thariat J, Schouman T, Brouchet A, et al. Osteosarcomas of the mandible: multidisciplinary management of a rare tumor of the young adult a cooperative study of the GSF‐GETO, Rare Cancer Network, GETTEC/REFCOR and SFCE. Ann Oncol 2013;24:824–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee RJ, Arshi A, Schwartz HC, Christensen RE. Characteristics and prognostic factors of osteosarcoma of the jaws: a retrospective cohort study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;141:470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]