Summary

BRAF inhibitors have revolutionized treatment of mutant BRAF metastatic melanomas. However, resistance develops rapidly following BRAF inhibitor treatment. We have found that BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines are more sensitive than wild-type BRAF cells to the small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor dovitinib. Sensitivity is associated with inhibition of a series of known dovitinib targets. Dovitinib in combination with several agents inhibits growth more effectively than either agent alone. These combinations inhibit BRAF-mutant melanoma and colorectal carcinoma cell lines, including cell lines with intrinsic or selected BRAF inhibitor resistance. Hence, combinations of dovitinib with second agents are potentially effective therapies for BRAF-mutant melanomas, regardless of their sensitivity to BRAF inhibitors.

Keywords: Dovitinib, Mutant BRAF, Combination therapy, Vemurafenib resistance, MEK inhibitor

Introduction

Incidence of melanoma is increasing faster than that of other solid tumors (Eggermont et al., 2014). With distant metastatic dissemination, survival rates for melanoma are a median of six to nine month, with 85% mortality within three years of diagnosis (Eggermont et al., 2014). Activating mutations in the protein kinase BRAF occur in approximately one half of melanomas (Flaherty and Fisher, 2011). Inhibitors of activated BRAF are US FDA-approved for treatment of mutant BRAF melanomas; concomitant inhibition of BRAF and the downstream protein kinase MEK is also US FDA-approved for mutant BRAF melanomas (Chapman et al., 2011; Flaherty et al., 2012). However, resistance to both compounds, either alone or in combination, persists (Bucheit and Davies, 2014; Long et al., 2014; Wagle et al., 2014). Additional treatment strategies, such as using additional combination therapies, will need to be uncovered in order to treat these patients refractory to combined BRAF and MEK inhibition.

Combinatorial screens to combat BRAF and MEK inhibitor resistance have identified actionable combinations that do not include MEK inhibitors (Held et al., 2013; Roller et al., 2012). The combination of an AKT inhibitor (MK-2206) and EGFR/HER2 (lapatinib) inhibitor was preferentially active against mutant BRAF melanomas; the triple combination of vemurafenib, MK-2206, and lapatinib was the most effective at inhibiting the growth of both vemurafenib-sensitive and resistant cell lines (Held et al., 2013). Deregulated receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling is a common mechanism of intrinsic or adaptive resistance to vemurafenib (Girotti et al., 2013; Held et al., 2013; Nazarian et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2012; Yadav et al., 2012). Several RTKs contribute to survival of mutant BRAF melanoma (Easty et al., 2011; Tworkoski et al., 2011), including KIT, FGFR, PDGFRs, and members of the ERBB family (Abel et al., 2013; Metzner et al., 2011; Nazarian et al., 2010; Sabbatino et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2013). Our earlier combinatorial screen revealed that the RTK inhibitor dovitinib is a particularly effective agent in growth inhibition of BRAF-driven melanomas (Held et al., 2013). Dovitinib (CHIR-258/TKI-258) is a multiple RTK inhibitor that is in clinical trials for several cancers (Escudier et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2013; Milowsky et al., 2014; Motzer et al., 2014; Trudel et al., 2005). Here, we investigate the nature and activity of potential dovitinib targets in BRAF-driven melanoma. The results may facilitate optimal selection of melanoma patients for treatment with dovitinib and other multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors in combination with other agents, and identify ways to enhance impact of BRAF/MEK dual inhibitor treatment.

Results

Dovitinib inhibits mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines growth independent of BRAF kinase activity

In our screen of 150 anti-cancer agents against twenty-seven melanoma cell lines (Held et al., 2013), mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines were selectively sensitive to BRAF inhibitors (PLX-4032, PLX-4720, GDC-0879) and MEK inhibitor U0126 (Fig. 1A). Mutant BRAF melanomas were also sensitive to the green tea polyphenol EGCG (epigallocatechin-3-gallate), which induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in melanomas (Fig. 1A) (Nihal et al., 2005). The broad spectrum RTK inhibitor dovitinib ranked just below EGCG, BRAF inhibitors, and MEK inhibitor, in selectivity for BRAF-mutated melanomas (Figs. 1A, 1B, 1C). There was no correlation between sensitivity to dovitinib and either vemurafenib or MEK inhibitors CIP-1374 and U0126 (Figs. 1D and S1), suggesting that dovitinib acts somewhat differently from agents that target RAF or MEK.

Figure 1. Mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines are more sensitive to dovitinib than those without BRAF mutations.

(A) Difference in average GI50 values (in µM) between 12 wild-type BRAF melanoma and 14 mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines (Held et al., 2013). The highest drug concentration tested (usually 10µM) was used for cell lines that did not reach 50% growth inhibition. (B) Comparison of dovitinib GI50 values between mutant (BRAF*) and wild-type BRAF cell lines * p = 0.0328, Mann-Whitney test. (C) Maximum percent growth inhibition by dovitinib in BRAF-mutant, RAS-mutant, or BRAF,RAS wild-type. One-way ANOVA. P = 0.0642. (D) Scatter plot of dovitinib GI50 versus vemurafenib GI50 of mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines. Spearman’s ρ = 0.3103, P = 0.2773. (E) Phosphorylation of GST-MEK fusion protein by recombinant BRAF incubated with 25 µM PLX-4720 or 25 µM dovitinib. (F) Immune complex kinase assays of BRAF immunoprecipitated from BRAF-mutant lines 501 MEL and YUSIK incubated with 10 µM PLX-4720 or 10 µM dovitinib.

As dovitinib is a protein kinase inhibitor, we determined if dovitinib directly inhibits BRAF kinase activity (Fig. 1E). Dovitinib (25 µM) only weakly suppressed phosphorylation of a GST-MEK peptide by recombinant WT BRAF in comparison to BRAF inhibitor PLX-4720 (Fig. 1E). Moreover, 10 µM dovitinib only weakly inhibited the kinase activity of BRAF immune complexes isolated from cells with BRAF mutations relative to DMSO vehicle control (Fig. 1F). These results are consistent with kinase inhibitor selectivity profiling (Davis et al., 2011).

Type III, IV, and V RTK Targets of Dovitinib in Melanoma

As dovitinib had only modest effects on BRAF activity, we sought to identify other targets. Dovitinib inhibits Type III, IV, and V RTKs (Trudel et al., 2005). RNA profiling of BRAF-driven melanoma lines showed that, among the sensitive kinases, KIT, CSF-1R, FGFR1, and FGFR3 mRNAs are expressed at high levels (Fig. 2A). Expression of PDGFRβ, FGFR3, and KIT was confirmed by immunoblotting with some differences in rank order (Fig. 2B and (Tworkoski et al., 2011)).

Figure 2. Type III, IV, and V receptor tyrosine kinases are expressed in mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines.

(A) Expression of RTK targets of dovitinib in BRAF mutant melanoma cell lines. RTKs are ordered from left to right by KD values as reported in (Trudel et al., 2005). (B) Immunoblots of different dovitinib RTK targets in mutant BRAF melanoma cells. (C and D) Summary of RTK phosphorylation determined using receptor capture arrays to analyze lysates from BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines, either without (C) or with (D) pervanadate pre-treatment. Activation scores are derived from visual inspection of each phospho-RTK array and assigned a value on a scale between 0 (no phosphorylation intensity) and 5 (very high phosphorylation intensity). Adapted from data reported in (Tworkoski et al., 2011). (E) Scatter plot of KIT phosphorylation (Tworkoski et al., 2011) versus dovitinib GI50 values (Held et al., 2013) in mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines that were pre-treated with pervanadate. Spearman ρ = −0.2958, not significant (P = 0.3214).

We surveyed endogenous and pervanadate-stimulated Tyr phosphorylation of potential dovitinib RTK targets in several BRAF-mutant lines with RTK capture arrays (Tworkoski et al., 2011). Among the known dovitinib RTK targets (Trudel et al., 2005), FGFR3 was the most frequently active RTK in our panel of mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines (Fig. 2A and 2C). Activation of VEGFR3, FLT3, KIT, and other dovitinib targets was more evident after tyrosine phosphatase inhibition with pervanadate (Fig. 2D). Among those RTKs, phosphorylation of KIT correlated best, but not significantly, with low dovitinib GI50 (Figs. 2E and S2A–B). YUSTE and YUKSI cells (cell lines without active KIT) may instead respond through inhibition of dovitinib targets FGFR3, FLT3, and/or VEGFR3 (Fig. 2D). There are some discrepancies between immunoblotting, which is generally more accurate, and receptor capture array analysis, as we have noted earlier (Tworkoski et al., 2011).

Reverse-phase protein analysis (RPPA) was used to determine if there was an association between expression or phosphorylation of other signaling proteins and dovitinib response (Fig. 3A). KIT protein expression was most tightly associated with dovitinib response, but the association was not statistically significant (Figs. 3B and 3C). The KIT-low, dovitinib-responsive cell line YUKSI had high protein expression of PDGFRβ (Fig. 3A). Baseline expression of other proteins and phosphopeptides significantly correlated with dovitinib response. These included positive associations with P-Thr345 NDRG1, caspase-8, Tyro3, and P-Tyr705 STAT3 and negative associations with Twist and P-Ser1981 ATM (Fig. 3D). However, dovitinib did not affect P-Tyr705 STAT3 (data not shown). Overall, multiple RTK targets of dovitinib are expressed and active in melanoma cell lines, and no single RTK is uniquely associated with dovitinib response.

Figure 3. RPPA analysis of BRAF-mutant melanoma lines.

(A) Heatmap of (log(2)) expression. (B) Scatter plot of KIT protein expression determined by RPPA versus dovitinib GI50. (C) Spearman ρ and P values for correlation of all RTKs analyzed by RPPA with dovitinib GI50 response. (D) Spearman ρ and P values for proteins analyzed by RPPA that correlated significantly with dovitinib GI50.

RTK capture array analysis was used to identify receptors inhibited by dovitinib in three mutant BRAF lines with different patterns of active receptors (Fig. 4A). For greatest sensitivity in identifying candidates, cells were pretreated with pervanadate, and incubated with 5 µM dovitinib. TYRO3, MERTK, ERBB3, KIT, ALK, EPHA10, and RYK were each inhibited in at least two lines. We directly evaluated the impact of dovitinib on Tyr phosphorylation of candidate receptors and/or associated proteins by anti-PTyr immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting for specific RTKs. Dovitinib reduced immunoprecipitation of phosphorylated KIT and TYRO3 (Figs. 4B and S3). Similar experiments with ERBB3 and MERTK yielded variable and inconclusive results (data not shown).

Figure 4. Dovitinib inhibits multiple RTKs in mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines.

(A) RTK capture arrays of BRAF-mutant melanoma cell lines that were incubated with pervanadate (20 min.) and 5 µM dovitinib or 0.1% DMSO for three hours and probed with anti-PTyr. (B and C) Anti-PTyr immunoprecipitates of cells incubated with or without 1 µM dovitinib for three hours and pervanadate for 20 min were immunoblotted (“WB”) with the indicated antibodies.

Dovitinib at a lower concentration (1 µM) also reduced recovery of KIT in anti-PTyr immune complexes (Fig. 4B). Since only a subset of melanoma cells express high protein levels of KIT (Fig. 3A), we investigated other potential dovitinib targets in KIT-low YUKSI cells (Figs. 2B, 3A). Dovitinib (1 µM) inhibited phosphorylation of PDGFRβ and phosphorylated FGFR1 (Fig. 4C). Taken together, dovitinib inhibits signaling from several RTKs active in melanoma cell lines.

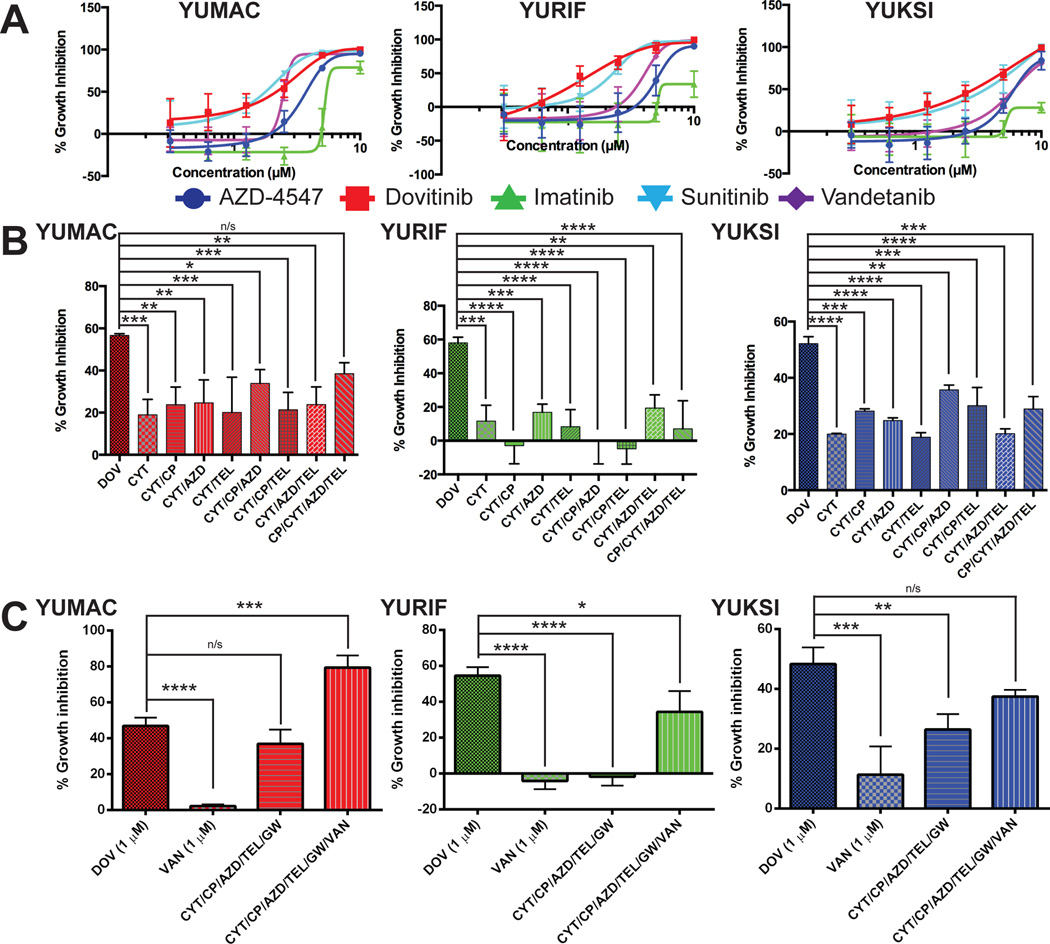

We next compared dovitinib to other RTK inhibitors imatinib, AZD-4547, and vandetanib, that inhibit overlapping sets of RTK targets (Fig. 5A, Table S2). Dovitinib was more effective than more specific RTK inhibitors at inhibiting growth of melanoma cells. Dovitinib response of YUMAC and YUKSI cells closely paralleled the growth inhibitory effect of sunitinib. Sunitinib has an even broader kinase target range than dovitinib, but shares several potential targets (Davis et al., 2011). As dovitinib acts by inhibiting multiple targets, we investigated if combinations of more specific inhibitors would mimic dovitinib response. CP-673451 (PDGFRβ), telatinib (KIT), CYT-387 (JAK2 and TBK1 (Zhu et al., 2014)), and AZD-4547 were tested singly and in combination in YURIF, YUMAC (both KIT, FGFR3 active), and YUKSI cells (FGFR1, PDGFRβ). Four-way combinations of these agents (1 µM each agent) were less effective than 1 µM dovitinib (Fig. 5B). A five-way combination, including the CSF-1R inhibitor GW-2580, was only able to match the dovitinib response in YUMAC cells (Fig. 5C). The dovitinib response was only matched in YUKSI cells following the addition of vandetanib to the five-agent combination. YURIF were significantly more sensitive to dovitinib than the RTK inhibitor combinations tested (Fig. 5C). Overall, concomitant treatment with several specific RTK inhibitors is necessary to equal the dovitinib response.

Figure 5. Inhibition of several RTKs is necessary for dovitinib to inhibit growth.

(A) Dose-response of growth inhibition with 72 hours of treatment of indicated cell lines with dovitinib, sunitinib, AZD-4547, imatinib, or vandetanib. Four parameter logic curve fits were generated with Prism software. (B) Growth inhibition by single agent and combination treatments over three days. All compounds were 1 µM in (B) and (C). DOV, dovitinib; CYT, CYT-387; CP, CP-673451; TEL, telatinib; AZD, AZD-4547; GW, GW-2580; VAN, vandetanib. One-way ANOVA – YUMAC p < 0.01, YURIF p < 0.0001, YUKSI p < 0.0001. Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test – p * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001, n/s is not significant. (C) One-way ANOVA – p < 0.0001 for all three cell lines.

Dovitinib Combines Effectively with Several Other Small Molecule Inhibitors Regardless of Vemurafenib Sensitivity

BRAF mutant melanomas are commonly treated with BRAF inhibitors, alone or in combination with MEK inhibitors (Chapman et al., 2011; Flaherty et al., 2012). AKT inhibitors also combine effectively with several kinase inhibitors to inhibit tumor growth (Atefi et al., 2011; Held et al., 2013; Lassen et al., 2014). We determined if the combination of dovitinib with BRAF, MEK, or AKT inhibitors improves efficacy. Indeed, in a combinatorial growth screen (Held et al., 2013), we found that dovitinib in combination with vemurafenib, CIP-1374 (MEK inhibitor), or MK-2206 (AKT inhibitor) was more effective than either single agent for a number of vemurafenib-sensitive BRAF mutant cell lines (Figs. 6A, 6B, 6C). This interaction was confirmed for vemurafenib, selumetinib (MEK inhibitor), and MK-2206 (Figs. S4A, S4B). Dovitinib plus vemurafenib, selumetinib, or MK-2206 inhibited clonogenicity more than either agent in mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines (Fig. 6D, 6E). Dovitinib in combination with other inhibitors of the PI3K/AKT pathway also inhibited growth more than either agent alone (Fig. 6F). Therefore, dovitinib may be an effective partner agent with several inhibitors of the MAPK and AKT pathways.

Figure 6. Effect of dovitinib combinations on vemurafenib-sensitive BRAF-mutant melanoma cells.

(A–C) Drug interaction maps of dovitinib in combination with (A) vemurafenib, (B) CIP-1374, or (C) MK-2206. Red indicates observed combination values for superadditive interaction based on Bliss independence model (Borisy et al., 2003). Green indicates calculated Bliss additive value for combinations that are subadditive. Yellow indicates calculated Bliss independence value (if red in bar) or observed growth inhibition value (if green in bar). Compound concentrations: (High (H), Medium (M), and Low (L)): dovitinib (2.74 µM, 1 µM, and 386 nM), vemurafenib (680 nM, 66 nM, 36 nM), CIP-1374 (122 nM, 32 nM, 9 nM), and MK-2206 (5.48 µM, 1.98 µM, 475 nM). (D). Representative clonogenicity assays of dovitinib, vemurafenib, and the combination. Dovitinib concentration is 375 nM and vemurafenib is 300 nM, except YUMAC where dovitinib and vemurafenib were 200 nM and 100 nM, respectively. (E) Representative clonogenicity assays of YURIF cell line treated with 375 nM dovitinib with or without selumetinib or MK-2206. (F) Growth inhibition of dovitinib in combination with inhibitors of different components of PI3K/AKT pathway. Rapamycin, 18 nM; GDC-0941, 1 µM; MK-2206, 1.5 µM; GSK2334470, 5 µM; BYL-719, 1 µM. Paired t-test – p * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001.

Approximately 20–40% of melanoma patients with BRAF mutations are intrinsically resistant to vemurafenib, and one fourth do not respond to the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib (Acquaviva et al., 2014; Girotti et al., 2013). Since dovitinib effectively partnered with several small molecule inhibitors in vemurafenib-sensitive lines (Fig. 6), we evaluated whether these combinations would affect melanomas intrinsically resistant to vemurafenib. The YUKSI cell line was used as a model of both intrinsic activated BRAF and MEK inhibitor resistance (Held et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2012; Thumar et al., 2014). In our previous combination analyses with YUKSI (Held et al., 2013), the vemurafenib/dovitinib combination was superior to either single-agent (Fig. 7A). The effectiveness of the combination (with lower dovitinib concentrations (375 nM)) over each single agent was further confirmed with clonogenicity experiments (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Effect of dovitinib combinations on vemurafenib-resistant YUKSI cells.

(A) Drug interaction maps of dovitinib and vemurafenib, as in the legend to Fig. 6. (B) Representative clonogenicity assays for cells treated with vemurafenib, dovitinib, or both. (C) Drug interaction maps of dovitinib and MK-2206 or CIP-1374. (D) Growth inhibition by single agents and combinations of dovitinib, vemurafenib (VEM), selumetinib (SEL), and MK-2206.

Combinatorial screening also revealed that dovitinib in combination with CIP-1374 or MK-2206 is superior to either alone. Follow-up CellTiterGlo growth experiments confirmed these interactions (Fig. 7C). In multiple intrinsically vemurafenib-resistant lines, triple combinations of dovitinib, vemurafenib, and MK-2206/selumetinib inhibited growth more than any double combination (Figs. 7D and Fig. S5A). However, in one cell line (YUKOLI), selumetinib did not further enhance the effects of dovitinib and vemurafenib (Fig. S5A).

In contrast to BRAF-driven melanomas, most colorectal carcinoma patients with BRAFV600E mutations do not respond to vemurafenib; this is due to adaptive activation of RTKs such as EGFR (Corcoran et al., 2012; Prahallad et al., 2012). The dovitinib-vemurafenib combination inhibits the growth of the vemurafenib-resistant colorectal cancer cell line RKO (Fig. S5B). Immunoblots reveal that RKO has phosphorylated FGFR (Fig. S5C). No total KIT or PDGFRβ protein was observed (data not shown). Together, this data suggests that intrinsically-vemurafenib resistant melanoma and colon cancer cell lines are responsive to dovitinib in combination with MEK and AKT pathway inhibitors.

We selected a vemurafenib resistant cell line (YUMAC XR5MC8) resistant to 5µM vemurafenib to model tumors with acquired vemurafenib resistance (Fig. 8A). Dovitinib plus maintenance vemurafenib treatment was more effective on these cells than either single agent (Fig. 8B). Dovitinib increased the effectiveness of MK-2206 on these cells, and the triple combination of dovitinib, vemurafenib, and MK-2206 yielded an even greater growth inhibitory response (Fig. 8B). YUMAC XR5MC8 cells are sensitive to the combination of the two agents, although they are resistant to vemurafenib and selumetinib as single-agents, (Fig. 8C). Dovitinib further enhanced the growth inhibition of combined vemurafenib and selumetinib treatment at low selumetinib concentrations (Fig. 8C). Hence, dovitinib is an effective partner agent in double or triple combinations with AKT and MAPK pathway inhibitors. These treatments work best in the continued presence of vemurafenib.

Figure 8. Dovitinib combinations in cell lines with acquired vemurafenib or dual vemurafenib and selumetinib resistance.

(A) Generation of vemurafenib-resistant (XR5MC8) and vemurafenib-and-selumetinib resistant (YUMAC DualR) lines from YUMAC parental cells. (B) Growth inhibition by single agents and combinations of dovitinib (1 µM), vemurafenib (5 µM), and MK-2206 (1.5 µM). (C) Growth inhibition by single agents and combinations of dovitinib (1 µM), vemurafenib (5 µM), selumetinib (noted in Figure), or both. (D and F) Immunoblots following 3 hr (D) or 24 hr (F) of treatment of YUMAC XR5MC8 cells with indicated inhibitors. (E) Final percent tumor volume change over two weeks of treatment with either control chow and vehicle gavage (CTRL/VEH), control chow with dovitinib gavage (CTRL/DOV), PLX-4720 chow with vehicle gavage (PLX/VEH), or PLX-4720 chow and dovitinib gavage (PLX/DOV). All of the control chow and gavage animals and one PLX-4720 chow, control gavage mouse were sacrificed one day prior to the end of the experiment due to large tumor size. Final measurements taken at time of sacrifice were used to determine change from baseline. One-way ANOVA p = 0.0162. Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test p < 0.05. (G) Growth inhibition of YUMAC DualR by single agents and combinations of dovitinib, vemurafenib, and selumetinib.

YUMAC XR5MC8 cells have high levels of P-ERK (Figs. 8D, 8F). Single agent dovitinib did not affect P-ERK levels, and slightly enhanced P-AKT. As expected, vemurafenib reduced P-ERK, and P-ERK levels were reduced even further in the presence of dovitinib. Likewise, MEK inhibitor selumetinib alone reduced P-ERK, and these levels were further reduced in the presence of dovitinib (3 hours only, Fig. 8D). Triple combinations of dovitinib, vemurafenib, and selumetinib reduced P-ERK levels even further. Interactions in the AKT pathway were more complex, and efficacy of dovitinib in combination with AKT inhibitor MK-2206 may work through a different mechanism (Fig. 8D, 8F). YUMAC XR5MC8 cells have moderate levels of baseline P-Ser473. P-AKT is reduced by vemurafenib and by selumetinib, suggesting that AKT pathway activation is mediated through cross-talk with the RAF/MAPK pathway. In contrast, dovitinib actually enhances P-Ser473 AKT, which is reduced to baseline levels in combination with either vemurafenib or selumetinib. P-AKT in the double combinations of dovitinib with in vemurafenib or selumetinib, is similar to P-AKT in the triple combination, so this moderate difference in P-AKT does not explain the greater efficacy of triple combinations. Rather, the major incremental impact for the triple combination appears to be the severe suppression of MAPK signaling.

Results with the AKT inhibitor MK-2206 are somewhat different. MK-2206 suppressed P-AKT as a single agent and in all combinations. Over 24 hours (Fig. 8F), MK-2206 increases P-ERK, either alone or in combination with dovitinib, and P-ERK level in the dovitinib/ MK-2206/vemurafenib triple combination is similar to P-ERK in the dovitinib/vemurafenib combination, which is less effective at growth inhibition (Fig. 8B). Hence the improved growth inhibition by dovitinib/MK-2206 and dovitinib/MK-2206/vemurafenib combinations (Fig. 8B) is not explained by impact on P-ERK. Instead, MK-2206 evidently cooperates with dovitinib and vemurafenib through its direct impact on PI3K pathway signaling, in a context of greater residual P-ERK than in the dovitinib, vemurafenib, selumetinib combination. Both of the triple combinations promote greater apoptotic signaling, as indicated by increased accumulation of proapoptotic BIM (Fig. 8F).

The dovitinib/vemurafenib combination significantly inhibited growth of YUMAC XR5MC8 cells as mouse xenografts (Fig. 8E and S6). Combination-treated mice reduced tumor growth compared to each single-agent treated cohort and control cohort (Fig. 8E and S6), without overt toxicity.

Although use of combinations of BRAF and MEK inhibitors prolongs progression-free survival, resistance to these combinations still occurs (Wagle et al., 2014). To model this problem, YUMAC XR5MC8 was further selected with 150 nM selumetinib to produce a monoclonal dual BRAF-MEK inhibitor resistant line (YUMAC DualR) (Fig. 8A). The triple combination of dovitinib, vemurafenib, and selumetinib was superior at inhibiting growth of these cells to double combinations (Fig. 8G). Interestingly, all three lines responded similarly to dovitinib treatment, so dovitinib cross-resistance was not selected in this model (Fig. 8G). In another doubly resistant model we produced, (Fig. S7A), progressive selection for dovitinib resistance was observed, but the triple combination of dovitinib, vemurafenib, and selumetinib was still the most effective at inhibiting in vitro growth (Fig. S7B). Therefore, dovitinib in combination with vemurafenib and selumetinib effectively inhibits growth in melanoma cells that have acquired resistance to combined vemurafenib and selumetinib treatment.

Discussion

Although targeted therapy has improved survival of patients with BRAF mutant melanoma, resistance to these therapies remains a significant clinical hurdle. We found that the multi-RTK inhibitor dovitinib selectively inhibits the growth of melanoma cultures with BRAF mutations. Dovitinib inhibits phosphorylation of multiple RTK targets that are frequently expressed and active in melanoma cells, including KIT, PDGFRβ, and FGFR. Concomitant treatment with multiple inhibitors with greater specificity is required to mimic effects of dovitinib in vitro. Combinations of dovitinib with inhibitors of the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways, including vemurafenib, selumetinib, and MK-2206, reduce growth and colony formation in BRAF mutant cell lines substantially more than either agent alone, regardless of vemurafenib sensitivity. Triple dovitinib/vemurafenib/selumetinib or dovitinib/vemurafenib/MK-2206 combinations are more effective than the single agents or pairwise combinations.

BRAF mutant melanoma cells were more sensitive to dovitinib than were lines with WT BRAF. This may explain the variable performance of dovitinib in earlier studies and clinical trials that did not stratify melanoma by genotype (Kim et al., 2011; Sarker et al., 2008; Zipser et al., 2011). RAS mutant melanomas are insensitive to many agents (Held et al., 2013). Blockade of RTKs activated through BRAF-induced autocrine circuits, or activated by independent mechanisms as resistance to BRAF inhibition develops, may have major impact on mutant BRAF melanoma growth (Abel et al., 2013; Schlegel et al., 2013; Tworkoski et al., 2011).

We found that KIT is a common dovitinib target in KIT-expressing melanomas. In other cell lines, dovitinib inhibits FGFRs and PDGFRs. Increased kinase activity of PDGFRβ leads to acquired vemurafenib resistance (Nazarian et al., 2010; Yadav et al., 2012). PDGFRβ is also highly expressed in the intrinsically vemurafenib resistant cell line YUKSI. So, dovitinib may be useful in both ab initio and acquired vemurafenib refractory settings, especially as 20–40% of BRAF mutant melanoma patients are initially refractory to BRAF or MEK inhibitors (Acquaviva et al., 2014; Girotti et al., 2013).

FGF signaling is critical for melanoma biology. FGF2 (basic fibroblast growth factor, bFGF), in conjunction with cyclic AMP stimulators promotes growth in a minimal medium for melanocyte cell cultures (Halaban et al., 1987). Transducing FGF2 into melanocytes induces transformation, and the expression of dominant-negative FGFRs inhibits the growth of melanoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo (Metzner et al., 2011; Nesbit et al., 1999). Antisense suppression of either FGFR1 or bFGF inhibits the in vitro or in vivo growth of melanoma tumors (Becker et al., 1992; Becker et al., 1989; Wang and Becker, 1997). Many melanoma cell lines have active FGFRs (Easty et al., 2011; Tworkoski et al., 2011), and increased activity of FGFRs leads to BRAF inhibitor resistance (Yadav et al., 2012).

Dovitinib was more effective than combinations of more specific inhibitors. Indeed, combinations with up to six kinase inhibitors with greater specificity within the dovitinib target spectrum were necessary to mimic effects of dovitinib treatment. In this context, dovitinib most closely resembles the multi-RTK inhibitor sunitinib. Dovitinib is more effective than sunitinib on clear cell renal cell carcinoma tumorgrafts (Sivanand et al., 2012), and in our screen, sunitinib was not selectively effective on BRAF-mutant melanoma. The strong impact of both dovitinib and sunitinib presumably reflects both the concomitant activity of multiple RTK targets in BRAF-driven melanomas (Tworkoski et al., 2011) and the need to block one or more secondary resiliency circuits that are activated following primary target inhibition.

Combination therapies will be necessary to fully capitalize on the utility of signaling-targeted therapy. Combinatorial screening indicated that dovitinib combinations with inhibitors of the MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways outperformed either single agent. Dovitinib enhanced the effects of several PI3K/AKT/PDK1 pathway inhibitors in mutant BRAF cells. Dovitinib combined with PI3K/AKT/PDK1 pathway inhibitors may interfere with the ability of the cells to circumvent vemurafenib treatment, as activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway is a common vemurafenib resistance mechanism. Interestingly, these combinations are active without direct MAPK pathway inhibition, and impact of the double combinations on MAPK signaling can be moderate (Fig. 8). Suppression of the PI3K pathway combined with upstream blockade of RTKs may mitigate the effects of the driving mutation by removing the support roles of these pathways necessary for survival of the mutant BRAF cells (Held et al., 2013).

In our single agent studies, dovitinib inhibits BRAF-driven melanoma through interference with tonically active RTKs. Baseline activation of non-mutated receptor kinases commonly occurs in melanoma (and other solid tumors), and represents a therapeutic opportunity that is largely unexploited. Adaptive activation of RTKs in response to BRAF inhibitors is a common mechanism of resistance. RTKs that cause adaptive resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors include AXL, EGFR, ERBB3, and PDGFRβ (Abel et al., 2013; Kugel and Aplin, 2014; Muller et al., 2014; Rebecca et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2014). Secreted growth factors including EGF, HGF, and FGF, can also re-activate MAPK signaling following BRAF inhibitor treatment, leading to BRAF inhibitor resistance (Lito et al., 2012; Straussman et al., 2012; Wilson et al., 2012). RTKs can also be activated following AKT inhibitor treatment and re-activate the MAPK pathway (Chandarlapaty et al., 2011; Held et al., 2013). The potential of dovitinib to inhibit adaptively-activated receptors will likely be important in treatment settings. as RTKs serve as crucial adaptive nodes through which cancer cells re-activate non-inhibited pathways. Combinations of dovitinib with vemurafenib and selumetinib or various PI3K pathway inhibitors may achieve greater effect by eliminating tumor escape routes.

Clinical resistance to combination BRAF and MEK inhibitor treatment affects many patients (Wagle et al., 2014), so there is a pressing need to establish therapeutic options for this dual refractory population. We developed two doubly-resistant cell lines to determine if dovitinib would be useful for prevention or treatment of resistance to BRAF/MEK-targeted combination therapy. Triple combinations of dovitinib, vemurafenib, and either MK-2206 or selumetinib are effective at inhibiting growth of these models. Finally, dovitinib combinations are effective on BRAF-driven colorectal carcinoma cells, which are intrinsically resistant to vemurafenib (Corcoran et al., 2012; Prahallad et al., 2012), and suggests broad utility in BRAF-driven cancers. Dovitinib is generally well tolerated in patients suggesting that this could be potentially useful as a combination partner agent (Escudier et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2013; Milowsky et al., 2014; Motzer et al., 2014). Overall, this work supports the promise of dovitinib and similar RTK inhibitors with multiple targets for the treatment of BRAF mutant melanoma, especially in the context of combination therapies, and to forestall or manage BRAF and MEK inhibitor resistance.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Reagents, and Antibodies

See Supporting Information for complete cell culture, reagent, and antibody information.

Drug screening

Single- and combination-agent screens have been described (Held et al., 2013). See Supporting Information for brief explanation.

Kinase assays

Chemiluminescent BRAF kinase assays (Millipore, B-RAF kinase assay KIT) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For BRAF immune complex kinase assays, cells were lysed and 1 mg of total protein was immunoprecipitated with 1–2 µg of BRAF antibody overnight with rocking, at 4°C, with kinase assays performed subsequently. Dovitinib and PLX-4720 were added to the kinase assays. Samples were transferred to PVDF after gel electrophoresis, blocked, and incubated overnight with a phospho-MEK antibody

RTK capture arrays

Cells were incubated with 5 µM dovitinib for 3 hours at 37°C, with 50 µM pervanadate added for the final twenty minutes. Cells were lysed and analyzed with the Proteome Profiler™ Human Phospho-RTK Array Kit (R&D Systems) as described (Tworkoski et al., 2011).

Reverse phase protein arrays

Cell lysates were analyzed by the RPPA Core Facility at the MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX). Heatmaps of log(2) transformed array expression values were generated using GENE-E heatmap generating software (Broad Institute).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

For complete protocols, see Supporting Information.

Cell growth

For non-automated assays, cells were manually plated into 96-well black-bottom plates at a density of 1,500 cells/well in 100 µL of medium. The next day, cells were incubated with test agents, vehicle control, or kill control (20% (v/v) DMSO). Three days later, 60 µL of CellTiterGlo was added to each well and luminescence was measured.

Colony formation assays

Cells were seeded at a density of 500–1,000 cells/well in six-well plates. Test agents were added the next day and once again three days later. After six days of drug treatment, cells were washed twice with medium, then maintained in medium for an additional four to six days. Cells were washed once with 1X PBS and then fixed for 10 min with ice cold methanol. Cells were stained for 30 min with 0.01% crystal violet and rinsed twice with water.

Xenografts

Six-week old, male, NCr nude mice (Taconic) were fed chow containing 417 mg/kg PLX-4720 (Research Diets, Inc., provided by Plexxikon) or control chow without inhibitor. After two days, the mice were injected in both rear flanks and upper shoulder with 106 YUMAC XR5MC8 cells. Small tumors were established in 15 days. The mice were then divided into four cohorts with five mice per cohort. Treatment groups consisted of control chow, no dovitinib; control chow, dovitinib; PLX-4720 chow, no dovitinib, and PLX-4720 chow, dovitinib. Dovitinib-treated mice were given 0.1 mL of dovitinib (30 mg/kg) in 1% methylcellulose via oral gavage. Mice not treated with dovitinib were given 0.1 mL of 1% methylcellulose via oral gavage. Mice were treated for 14 days and tumors were measured with a digital caliper. Tumor volume was calculated using V = 0.5233 × length × width × height.

Statistics

Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 or 6. Tests used for each figure are indicated in the Figure legend.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Scatter plots of dovitinib GI50 vs. CIP-1374 GI50 or U0126 GI50. CIP-1374 - Spearman ρ = 0.3505 and P = 0.2174. U0126 - Spearman ρ = 0.04464 and P = 0.8802.

Figure S2. (A) Scatter plots of RTK activation scores (scored 0 (least) to 5 (most active)) from phospho-RTK arrays, adapted from (Tworkoski et al., 2011), vs. dovitinib GI50 values for BRAF- mutant melanoma cell lines. Spearman ρ = 0.3474 (FLT3), 0.2152 (FGFR3), and 0.08452 (VEGFR3). P = 0.4214 (FLT3), 0.6036 (FGFR3), and 0.9286 (VEGFR3). (B) Scatter plot of sum of activation scores for each published target of dovitinib (Trudel et al., 2005), adapted from (Tworkoski et al., 2011), vs. dovitinib GI50 values for BRAF- mutant melanoma cell lines. Spearman ρ = −0.1509. P = 0.6179. Scores in both (A) and (B) are from pervanadate-treated samples.

Figure S3. Immunoblots for TYRO3 or KIT in anti-PTyr immunoprecipitates from indicated cell lines.

Figure S4. (A) Percent growth inhibition of indicated cell lines by dovitinib and vemurafenib following 72 hours of treatment. (B) Percent growth inhibition of indicated cell lines by dovitinib and vemurafenib following 72 hours of treatment. Confirmation of growth inhibition following seventy-two hours of treatment with dovitinib, MK-2206, and/or MEK inhibitor selumetinib.

Figure S5. (A and B) Percent growth inhibition of the indicated cell lines by dovitinib plus indicated agents after seventy-two hours of treatment. (C) Immunoblotting of pan-Phospho-FGFR in RKO protein lysates, in biological triplicate. 100 kDa and 150 kDa molecular weight markers indicated on right.

Figure S6. Change in percent tumor volume of YUMAC XR5MC8 xenografts from baseline (day 15) until sacrifice day 28 or day 29. Arrow indicates start of treatment (day 16) with dovitinib, PLX-4720, or controls. “X” indicates the number of mice sacrificed day 28. All five of the dual control treated mice (red) were sacrificed one day prior to the end of treatment due to large tumor volumes. One of the PLX-4720-only control mice was also sacrificed early due to large tumor burden.

Figure S7. (A) Development of polyclonal vemurafenib- and vemurafenib/selumetinib-dual resistant cell lines from YUSIT1 parental cells. (B) Percent growth inhibition of the three YUSIT1 cell lines after seventy-two hours of treatment with dovitinib plus indicated agents.

Significance.

Both initial and acquired resistance of melanoma to BRAF inhibitors is a major clinical problem. Targeted drug screening revealed that BRAF-mutant melanoma cells are relatively sensitive to dovitinib, a multi-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Dovitinib inhibits the growth and clonogenicity of several mutant BRAF melanoma cell lines, including vemurafenib-resistant cell lines. Vemurafenib-resistant xenografts were sensitive to the combination of dovitinib and vemurafenib. Additionally, cell cultures selected for dual BRAF inhibitor and MEK inhibitor resistance were sensitive to the triple combination of dovitinib, vemurafenib, and selumetinib. These data support the utility of dovitinib for combination therapy of BRAF-driven melanomas.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ruth Halaban for her ongoing leadership of the Yale SPORE in Skin Cancer and generously providing materials for this study, and to Antonella Bacchiocchi for developing and managing the SPORE cell cultures. We also thank Nicholas Theodosakis for helping with development of vemurafenib-resistant cell lines. This work was supported by a gift from an anonymous foundation (to MWB and DFS). CGL was supported by training grant T32GM007324, and MAH by a Leslie H. Warner postdoctoral fellowship awarded by the Yale Cancer Center. This manuscript has been used to fulfill in part the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Yale University.

References

- Abel EV, Basile KJ, Kugel CH, 3rd, Witkiewicz AK, Le K, Amaravadi RK, Karakousis GC, Xu X, Xu W, Schuchter LM, et al. Melanoma adapts to RAF/MEK inhibitors through FOXD3-mediated upregulation of ERBB3. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:2155–2168. doi: 10.1172/JCI65780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acquaviva J, Smith DL, Jimenez JP, Zhang C, Sequeira M, He S, Sang J, Bates RC, Proia DA. Overcoming acquired BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma via targeted inhibition of Hsp90 with ganetespib. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2014;13:353–363. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atefi M, Von Euw E, Attar N, Ng C, Chu C, Guo D, Nazarian R, Chmielowski B, Glaspy JA, Comin-Anduix B, et al. Reversing melanoma cross-resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors by co-targeting the AKT/mTOR pathway. PloS one. 2011;6:e28973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Lee PL, Rodeck U, Herlyn M. Inhibition of the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR-1) gene in human melanocytes and malignant melanomas leads to inhibition of proliferation and signs indicative of differentiation. Oncogene. 1992;7:2303–2313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Meier CB, Herlyn M. Proliferation of human malignant melanomas is inhibited by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides targeted against basic fibroblast growth factor. The EMBO journal. 1989;8:3685–3691. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borisy AA, Elliott PJ, Hurst NW, Lee MS, Lehar J, Price ER, Serbedzija G, Zimmermann GR, Foley MA, Stockwell BR, et al. Systematic discovery of multicomponent therapeutics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:7977–7982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1337088100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucheit AD, Davies MA. Emerging insights into resistance to BRAF inhibitors in melanoma. Biochemical pharmacology. 2014;87:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandarlapaty S, Sawai A, Scaltriti M, Rodrik-Outmezguine V, Grbovic-Huezo O, Serra V, Majumder PK, Baselga J, Rosen N. AKT inhibition relieves feedback suppression of receptor tyrosine kinase expression and activity. Cancer cell. 2011;19:58–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, Dummer R, Garbe C, Testori A, Maio M, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran RB, Ebi H, Turke AB, Coffee EM, Nishino M, Cogdill AP, Brown RD, Della Pelle P, Dias-Santagata D, Hung KE, et al. EGFR-mediated re-activation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:227–235. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MI, Hunt JP, Herrgard S, Ciceri P, Wodicka LM, Pallares G, Hocker M, Treiber DK, Zarrinkar PP. Comprehensive analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nature biotechnology. 2011;29:1046–1051. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easty DJ, Gray SG, O'byrne KJ, O'donnell D, Bennett DC. Receptor tyrosine kinases and their activation in melanoma. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2011;24:446–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2011.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont AM, Spatz A, Robert C. Cutaneous melanoma. Lancet. 2014;383:816–827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60802-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudier B, Grunwald V, Ravaud A, Ou YC, Castellano D, Lin CC, Gschwend JE, Harzstark A, Beall S, Pirotta N, et al. Phase II results of Dovitinib (TKI258) in patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20:3012–3022. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty KT, Fisher DE. New strategies in metastatic melanoma: oncogene-defined taxonomy leads to therapeutic advances. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:4922–4928. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A, Gonzalez R, Kefford RF, Sosman J, Hamid O, Schuchter L, Cebon J, Ibrahim N, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:1694–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girotti MR, Pedersen M, Sanchez-Laorden B, Viros A, Turajlic S, Niculescu-Duvaz D, Zambon A, Sinclair J, Hayes A, Gore M, et al. Inhibiting EGF receptor or SRC family kinase signaling overcomes BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma. Cancer discovery. 2013;3:158–167. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaban R, Ghosh S, Baird A. bFGF is the putative natural growth factor for human melanocytes. In vitro cellular & developmental biology : journal of the Tissue Culture Association. 1987;23:47–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02623492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held MA, Langdon CG, Platt JT, Graham-Steed T, Liu Z, Chakraborty A, Bacchiocchi A, Koo A, Haskins JW, Bosenberg MW, et al. Genotype-selective combination therapies for melanoma identified by high-throughput drug screening. Cancer discovery. 2013;3:52–67. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang YK, Yoo C, Ryoo BY, Lee JJ, Tan E, Park I, Park JH, Choi YJ, Jo J, Ryu JS, et al. Phase II study of dovitinib in patients with metastatic and/or unresectable gastrointestinal stromal tumours after failure of imatinib and sunitinib. British journal of cancer. 2013;109:2309–2315. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KB, Chesney J, Robinson D, Gardner H, Shi MM, Kirkwood JM. Phase I/II and pharmacodynamic study of dovitinib (TKI258), an inhibitor of fibroblast growth factor receptors and VEGF receptors, in patients with advanced melanoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:7451–7461. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kugel CH, 3rd, Aplin AE. Adaptive resistance to RAF inhibitors in melanoma. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2014;27:1032–1038. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassen A, Atefi M, Robert L, Wong DJ, Cerniglia M, Comin-Anduix B, Ribas A. Effects of AKT inhibitor therapy in response and resistance to BRAF inhibition in melanoma. Molecular cancer. 2014;13:83. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lito P, Pratilas CA, Joseph EW, Tadi M, Halilovic E, Zubrowski M, Huang A, Wong WL, Callahan MK, Merghoub T, et al. Relief of profound feedback inhibition of mitogenic signaling by RAF inhibitors attenuates their activity in BRAFV600E melanomas. Cancer cell. 2012;22:668–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long GV, Fung C, Menzies AM, Pupo GM, Carlino MS, Hyman J, Shahheydari H, Tembe V, Thompson JF, Saw RP, et al. Increased MAPK reactivation in early resistance to dabrafenib/trametinib combination therapy of BRAF-mutant metastatic melanoma. Nature communications. 2014;5:5694. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzner T, Bedeir A, Held G, Peter-Vorosmarty B, Ghassemi S, Heinzle C, Spiegl-Kreinecker S, Marian B, Holzmann K, Grasl-Kraupp B, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptors as therapeutic targets in human melanoma: synergism with BRAF inhibition. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2011;131:2087–2095. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milowsky MI, Dittrich C, Duran I, Jagdev S, Millard FE, Sweeney CJ, Bajorin D, Cerbone L, Quinn DI, Stadler WM, et al. Phase 2 trial of dovitinib in patients with progressive FGFR3-mutated or FGFR3 wild-type advanced urothelial carcinoma. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2014;50:3145–3152. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzer RJ, Porta C, Vogelzang NJ, Sternberg CN, Szczylik C, Zolnierek J, Kollmannsberger C, Rha SY, Bjarnason GA, Melichar B, et al. Dovitinib versus sorafenib for third-line targeted treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. The lancet oncology. 2014;15:286–296. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J, Krijgsman O, Tsoi J, Robert L, Hugo W, Song C, Kong X, Possik PA, Cornelissen-Steijger PD, Foppen MH, et al. Low MITF/AXL ratio predicts early resistance to multiple targeted drugs in melanoma. Nature communications. 2014;5:5712. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarian R, Shi H, Wang Q, Kong X, Koya RC, Lee H, Chen Z, Lee MK, Attar N, Sazegar H, et al. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature. 2010;468:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbit M, Nesbit HK, Bennett J, Andl T, Hsu MY, Dejesus E, Mcbrian M, Gupta AR, Eck SL, Herlyn M. Basic fibroblast growth factor induces a transformed phenotype in normal human melanocytes. Oncogene. 1999;18:6469–6476. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nihal M, Ahmad N, Mukhtar H, Wood GS. Anti-proliferative and proapoptotic effects of (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate on human melanoma: possible implications for the chemoprevention of melanoma. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:513–521. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, Beijersbergen RL, Bardelli A, Bernards R. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–103. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebecca VW, Wood E, Fedorenko IV, Paraiso KH, Haarberg HE, Chen Y, Xiang Y, Sarnaik A, Gibney GT, Sondak VK, et al. Evaluating melanoma drug response and therapeutic escape with quantitative proteomics. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2014;13:1844–1854. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.037424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roller DG, Axelrod M, Capaldo BJ, Jensen K, Mackey A, Weber MJ, Gioeli D. Synthetic lethal screening with small-molecule inhibitors provides a pathway to rational combination therapies for melanoma. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2012;11:2505–2515. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbatino F, Wang Y, Wang X, Flaherty KT, Yu L, Pepin D, Scognamiglio G, Pepe S, Kirkwood JM, Cooper ZA, et al. PDGFRalpha up-regulation mediated by sonic hedgehog pathway activation leads to BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma cells with BRAF mutation. Oncotarget. 2014;5:1926–1941. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarker D, Molife R, Evans TR, Hardie M, Marriott C, Butzberger-Zimmerli P, Morrison R, Fox JA, Heise C, Louie S, et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of TKI258, an oral, multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2008;14:2075–2081. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel J, Sambade MJ, Sather S, Moschos SJ, Tan AC, Winges A, Deryckere D, Carson CC, Trembath DG, Tentler JJ, et al. MERTK receptor tyrosine kinase is a therapeutic target in melanoma. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:2257–2267. doi: 10.1172/JCI67816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Kong X, Ribas A, Lo RS. Combinatorial treatments that overcome PDGFRbeta-driven resistance of melanoma cells to V600EB-RAF inhibition. Cancer research. 2011;71:5067–5074. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Moriceau G, Kong X, Koya RC, Nazarian R, Pupo GM, Bacchiocchi A, Dahlman KB, Chmielowski B, Sosman JA, et al. Preexisting MEK1 exon 3 mutations in V600E/KBRAF melanomas do not confer resistance to BRAF inhibitors. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:414–424. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivanand S, Pena-Llopis S, Zhao H, Kucejova B, Spence P, Pavia-Jimenez A, Yamasaki T, Mcbride DJ, Gillen J, Wolff NC, et al. A validated tumorgraft model reveals activity of dovitinib against renal cell carcinoma. Science translational medicine. 2012;4:137ra75. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, Davis A, Mongare MM, Gould J, Frederick DT, et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature. 2012;487:500–504. doi: 10.1038/nature11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Wang L, Huang S, Heynen GJ, Prahallad A, Robert C, Haanen J, Blank C, Wesseling J, Willems SM, et al. Reversible and adaptive resistance to BRAF(V600E) inhibition in melanoma. Nature. 2014;508:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumar J, Shahbazian D, Aziz SA, Jilaveanu LB, Kluger HM. MEK targeting in N-RAS mutated metastatic melanoma. Molecular cancer. 2014;13:45. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudel S, Li ZH, Wei E, Wiesmann M, Chang H, Chen C, Reece D, Heise C, Stewart AK. CHIR-258, a novel, multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the potential treatment of t(4;14) multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005;105:2941–2948. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tworkoski K, Singhal G, Szpakowski S, Zito CI, Bacchiocchi A, Muthusamy V, Bosenberg M, Krauthammer M, Halaban R, Stern DF. Phosphoproteomic screen identifies potential therapeutic targets in melanoma. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2011;9:801–812. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagle N, Van Allen EM, Treacy DJ, Frederick DT, Cooper ZA, Taylor-Weiner A, Rosenberg M, Goetz EM, Sullivan RJ, Farlow DN, et al. MAP kinase pathway alterations in BRAF-mutant melanoma patients with acquired resistance to combined RAF/MEK inhibition. Cancer discovery. 2014;4:61–68. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Becker D. Antisense targeting of basic fibroblast growth factor and fibroblast growth factor receptor-1 in human melanomas blocks intratumoral angiogenesis and tumor growth. Nature medicine. 1997;3:887–893. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TR, Fridlyand J, Yan Y, Penuel E, Burton L, Chan E, Peng J, Lin E, Wang Y, Sosman J, et al. Widespread potential for growth-factor-driven resistance to anticancer kinase inhibitors. Nature. 2012;487:505–509. doi: 10.1038/nature11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav V, Zhang X, Liu J, Estrem S, Li S, Gong XQ, Buchanan S, Henry JR, Starling JJ, Peng SB. Reactivation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway by FGF receptor 3 (FGFR3)/Ras mediates resistance to vemurafenib in human B-RAF V600E mutant melanoma. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:28087–28098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.377218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Wong P, Duan J, Jacobs B, Borden EC, Bedogni B. An ERBB3/ERBB2 oncogenic unit plays a key role in NRG1 signaling and melanoma cell growth and survival. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2013;26:408–414. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z, Aref AR, Cohoon TJ, Barbie TU, Imamura Y, Yang S, Moody SE, Shen RR, Schinzel AC, Thai TC, et al. Inhibition of KRAS-driven tumorigenicity by interruption of an autocrine cytokine circuit. Cancer discovery. 2014;4:452–465. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipser MC, Eichhoff OM, Widmer DS, Schlegel NC, Schoenewolf NL, Stuart D, Liu W, Gardner H, Smith PD, Nuciforo P, et al. A proliferative melanoma cell phenotype is responsive to RAF/MEK inhibition independent of BRAF mutation status. Pigment cell & melanoma research. 2011;24:326–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Scatter plots of dovitinib GI50 vs. CIP-1374 GI50 or U0126 GI50. CIP-1374 - Spearman ρ = 0.3505 and P = 0.2174. U0126 - Spearman ρ = 0.04464 and P = 0.8802.

Figure S2. (A) Scatter plots of RTK activation scores (scored 0 (least) to 5 (most active)) from phospho-RTK arrays, adapted from (Tworkoski et al., 2011), vs. dovitinib GI50 values for BRAF- mutant melanoma cell lines. Spearman ρ = 0.3474 (FLT3), 0.2152 (FGFR3), and 0.08452 (VEGFR3). P = 0.4214 (FLT3), 0.6036 (FGFR3), and 0.9286 (VEGFR3). (B) Scatter plot of sum of activation scores for each published target of dovitinib (Trudel et al., 2005), adapted from (Tworkoski et al., 2011), vs. dovitinib GI50 values for BRAF- mutant melanoma cell lines. Spearman ρ = −0.1509. P = 0.6179. Scores in both (A) and (B) are from pervanadate-treated samples.

Figure S3. Immunoblots for TYRO3 or KIT in anti-PTyr immunoprecipitates from indicated cell lines.

Figure S4. (A) Percent growth inhibition of indicated cell lines by dovitinib and vemurafenib following 72 hours of treatment. (B) Percent growth inhibition of indicated cell lines by dovitinib and vemurafenib following 72 hours of treatment. Confirmation of growth inhibition following seventy-two hours of treatment with dovitinib, MK-2206, and/or MEK inhibitor selumetinib.

Figure S5. (A and B) Percent growth inhibition of the indicated cell lines by dovitinib plus indicated agents after seventy-two hours of treatment. (C) Immunoblotting of pan-Phospho-FGFR in RKO protein lysates, in biological triplicate. 100 kDa and 150 kDa molecular weight markers indicated on right.

Figure S6. Change in percent tumor volume of YUMAC XR5MC8 xenografts from baseline (day 15) until sacrifice day 28 or day 29. Arrow indicates start of treatment (day 16) with dovitinib, PLX-4720, or controls. “X” indicates the number of mice sacrificed day 28. All five of the dual control treated mice (red) were sacrificed one day prior to the end of treatment due to large tumor volumes. One of the PLX-4720-only control mice was also sacrificed early due to large tumor burden.

Figure S7. (A) Development of polyclonal vemurafenib- and vemurafenib/selumetinib-dual resistant cell lines from YUSIT1 parental cells. (B) Percent growth inhibition of the three YUSIT1 cell lines after seventy-two hours of treatment with dovitinib plus indicated agents.