Abstract

Objective

To investigate relapse rates after the successful treatment of patients with non‐atypical endometrial hyperplasia who were randomised to either a levonorgestrel‐impregnated intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS; Mirena®) or two regimens of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) after primary histological response.

Design

A multicentre randomised trial.

Setting

Ten different outpatient clinics localised in hospitals and seven gynaecological private practices in Norway.

Population

One hundred and fifty‐three women aged 30–70 years with low‐ or medium‐risk endometrial hyperplasia met the inclusion criteria, and 153 completed the therapy.

Methods

Patients were randomly assigned to one of the following three treatment arms: LNG‐IUS; 10 mg of oral MPA administered for 10 days per cycle for 6 months; or 10 mg of oral MPA administered daily for 6 months. The women were followed for 24 months after ending therapy.

Main outcome measures

Histological relapse of endometrial hyperplasia.

Results

Histological relapse was observed in 55/135 (41%) women who had an initial complete treatment response. The relapse rates were similar in the three therapy groups (P = 0.66). In the multivariable analyses relapse was dependent on menopausal status (P = 0.0005) and estrogen level (P = 0.0007).

Conclusions

The risk of histological relapse of non‐atypical endometrial hyperplasia is high within 24 months of ceasing therapy with either the LNG‐IUS or oral MPA. Continued endometrial surveillance and prolonging progestogen therapy should be considered.

Tweetable abstract

Relapse of endometrial hyperplasia after successful treatment is independent of therapy regime.

Keywords: Endometrial hyperplasia, levonorgestrel‐impregnated intrauterine system, medroxyprogesterone acetate relapse of endometrial hyperplasia, recurrence of endometrial hyperplasia

Tweetable abstract

Relapse of endometrial hyperplasia after successful treatment is independent of therapy regime.

Introduction

Endometrial cancer develops from precursor lesions, but the risk of progression varies from <1% for simple endometrial hyperplasia (SH) and 3% for complex endometrial hyperplasia (CH) to 29% for atypical hyperplasia (AH).1 Surgery is considered the therapy of choice for AH, whereas oral progestogen therapy is more widely used for non‐atypical disease, in light of the lower risk of developing malignancy. The treatment response to oral progestogen has been shown to vary, however, with an average regression rate of 66%.2 Compared with oral therapy, some recent studies have shown that the levonorgestrel‐impregnated intrauterine system (LNG‐IUS) is superior as a primary therapy for non‐atypical endometrial hyperplasia (SH and CH).2, 3, 4, 5, 6 In a prior study, we found a complete treatment response after intrauterine therapy for all of the included women with non‐atypical endometrial hyperplasia, compared with a 54% response rate in the oral treatment group.5 Regression of endometrial hyperplasia was achieved in 94.8% of patients with the LNG‐IUS and in 84.0% of patients treated with oral progestogen.3 Our recently published randomised multicentre controlled trial (RCT) comparing the therapeutic effects of the LNG‐IUS and oral progestogen supported these earlier observational findings. We found a 100% therapeutic response for the LNG‐IUS compared with 69% for the low‐dose oral progestogen regimen after 6 months of treatment.7

Thus, sufficient knowledge exists to recommend the LNG‐IUS as a safe and effective therapy for medium‐ and low‐risk endometrial hyperplasia; however, it is known that histological relapse of endometrial hyperplasia after the initial therapeutic response is common. It remains uncertain whether the LNG‐IUS results in fewer relapses compared with oral therapy, and very few studies have investigated the time to relapse after completing therapy.5, 8, 9, 10 In a recent follow‐up investigation, Gallos and collaborators found that relapse occurred less often following treatment with the LNG‐IUS compared with oral therapy.9 Long‐term relapse rates were lower for complex non‐atypical hyperplasia compared with AH for both LNG‐IUS and oral progestogen treatment.9 In contrast, a cohort study with long‐term follow‐up showed no difference between the two therapy regimens. Relapse of hyperplasia occurred in 43% of women treated with LNG‐IUS compared with 40% of women who used oral progestogen in a study that included women with non‐atypical hyperplasia as well as AH.5

In light of the uncertainty around the risk of disease relapse after discontinuing currently recommended hormonal treatments, we followed up participants in our RCT for 24 months after ceasing treatment for endometrial hyperplasia to investigate whether the relapse rate and disease‐free interval differ according to therapy regime, progestogen dose, or route of administration.7 In addition, we explored the association between relapse rate and patient characteristics.

Methods

Trial design

This study was organised as a national, randomised, multicentre, follow‐up trial, with three parallel, equally sized arms that compared different progestogen therapy regimes for endometrial hyperplasia. A total of 153 of the 170 women who were originally randomised completed therapy in one of the following three treatment arms: LNG‐IUS (20 μg of levonorgestrel per 24 hours; Mirena®, Bayer); 10 mg of oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), administered for 10 days per cycle; or a continuous regimen of 10 mg of oral MPA, administered daily.7 After 6 months of treatment, all therapy was withdrawn, and each woman was followed at 6‐month intervals with a clinical examination and endometrial biopsy. The total follow‐up period for each woman was 24 months from the end of therapy. The study was designed according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement.11 No changes in design took place after the commencement of the trial.7 Women who were diagnosed with relapse of endometrial hyperplasia were censored in the analysis, but some of these women received additional therapy provided by their own gynaecologist, and these women were also followed for 24 months. The 18 women who failed to respond to the primary therapy were not included in the present study;7 however, the histological results regarding the presence or absence of hyperplasia after 24 months have been reported in the present article.

Participants

Women between 30 and 70 years of age with histologically confirmed endometrial hyperplasia, according to the WHO 94 classification,7 were eligible to participate in this trial. Women with hypersensitivity to progestogen, active genital infection, history of genital or mammary cancer, undiagnosed vaginal bleeding, liver disease, serious thrombophlebitis, or pregnancy were excluded.

Study setting, enrolment, and allocation

The study setting, enrolment, and allocation have been described in detail in a recent article.7 The study inclusion period was from 1 November 2011 to 1 January 2005. The treatment period was completed on 1 May 2012. The 24‐month follow‐up period for all of the women was completed on 1 May 2014. The treatment and follow‐up for all of the participating women was performed by gynaecologists in ten different outpatient clinics in hospitals and seven gynaecological private practices in Norway. All of the endometrial biopsies during the treatment and follow‐up periods were sent for histological evaluation at the Department of Clinical Pathology, University Hospital of North Norway.

Follow‐up

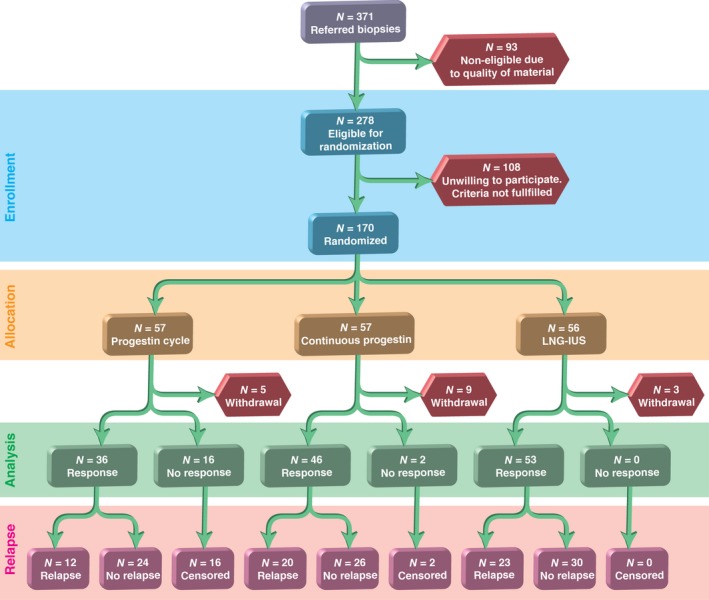

The regular control visits included a clinical consultation and endometrial biopsy performed by the gynaecologists at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. Secondary therapy for women with relapse was not described in the study protocol, but some of the women received additional progestogen therapy from their own gynaecologist (Figure 1). At each visit, the gynaecologist completed a separate information form that was sent to the Clinical Research Centre, University Hospital of North Norway, for electronic recording. The endometrial biopsies taken at each consultation were immediately soaked in a separate 10‐ml specimen jar in 10% formaldehyde. All of the biopsies were sent for investigation by light microscopy based on the modified WHO 94 classification.1

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the enrolment, allocation, results of the initial therapy, and relapses during the 24‐month follow‐up period.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome during follow‐up was relapse of endometrial hyperplasia, as assessed by light microscopy.7 Regular cycling endometrium or atrophic endometrium was considered to represent a persistent therapeutic effect. All of the clinical information (study form copies) from the study was sent by the gynaecologists to the Clinical Research Centre, University Hospital of North Norway, to be stored and blinded to the main investigators (AØ, ABV, MA, and BS). This information was concealed from the main investigators until the follow‐up period was completed, according to the principle of single blinding. Histological slides obtained during follow‐up were kept in the treatment database in the Department of Clinical Pathology, University Hospital North Norway. For the investigation of the endometrial biopsies, the pathologists and the engineers were always blinded to the patients’ treatment group. The treatment effect, i.e. the presence or absence of hyperplasia, was verified following consensus between two pathologists (AØ, who is a gynaecologic pathologist, and one routine pathologist).

Statistical methods

Standard parametric statistical tests, the Student's t‐test, and the chi‐square test were applied. Among the successfully treated patients, we compared the relapsing and non‐relapsing groups using time‐to‐failure methods such as Kaplan–Meier plots and log‐rank tests. Finally, a multivariable analysis was performed using ordinary proportional hazard regression. We examined models with the randomised groups as the first variable and the putative predictive variables added one by one; their contribution was evaluated as the difference in −2 log likelihood of the models with and without the respective variable. As a result of the non‐linearity of the continuous variables, dummy variables for categories were used in the regression models. stata 13.1 was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

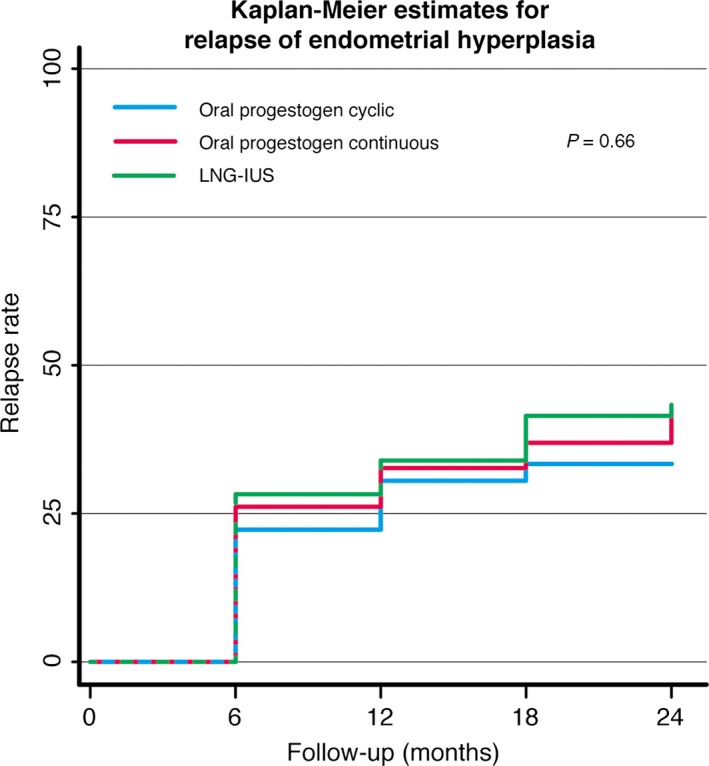

Of the 170 women recruited into the RCT, 153 completed 6 months of therapy with cyclic MPA (10 mg), continuous MPA (10 mg), or LNG‐IUS.7 Among these women, 135 were responders, whereas 18 women had persistent hyperplasia after 6 months of therapy.7 The 135 women who responded to therapy were followed and examined every 6 months during the 24‐month follow‐up period. No secondary therapy was given until relapse occurred. Fifty‐five of the 135 women (41%) relapsed histologically, but no differences were observed in the time to relapse according to therapeutic regimen (P = 0.66). Most relapses occurred during the first 6 months (63.6%), but relapses were observed during the entire 24‐month observation period (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve for relapse of hyperplasia during 24 months in women with initial regression treated with either the LNG‐IUS or oral progestogen.

Table 1 presents the baseline demographic data and the clinical variables that were included in the analysis of predictors of relapse. Age was significantly different between the two groups, but when taking the non‐linear relationship with the relapse rate into account, the significance vanished. In the multivariable analyses (Table 2), only menopausal status and estrogen level contributed significantly to the models. As a result of their high biological correlation, a model including both was not interpretable. Relapse was independent of parity and body mass index (BMI). Complex hyperplasia was the most frequent histopathological diagnosis in both groups. There appeared to be more relapses in the group with AH, although the difference was not significant.

Table 1.

Follow‐up for relapse over 24 months in 135 women after successful treatment of endometrial hyperplasia by the LNG‐IUS or by oral progestogen in an RCT

| Variable characteristics | Recurrence (n = 55) | No recurrence (n = 80) | Univariate test | Kaplan–Meier LogRank test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapy regimen | ||||

| MPA cyclic | 12 | 24 | ||

| MPA continuous | 20 | 26 | ||

| LNG‐IUS | 23 | 30 | P = 0.572 | P = 0.62 |

| Age (mean) | 45.8 | 48.5 | P = 0.014 | |

| ≤43 years | 17 | 16 | ||

| 44–48 years | 16 | 18 | ||

| 49–51 years | 15 | 21 | ||

| ≥52 years | 7 | 25 | P = 0.076 | P = 0.088 |

| WHO a | ||||

| SH | 6 | 13 | ||

| CH | 39 | 61 | ||

| AH | 10 | 6 | P = 0.14 | P = 0.12 |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 6 | 11 | ||

| 1 | 3 | 13 | ||

| 2 | 28 | 24 | ||

| 3+ | 18 | 32 | P = 0.056 | P = 0.066 |

| BMI (n = 133) | 27.0 | 26.5 | P = 0.59 | |

| ≤22 | 12 | 26 | ||

| 23–25 | 15 | 14 | ||

| 26–30 | 15 | 16 | ||

| ≥30 | 13 | 22 | P = 0.30 | P = 0.28 |

| Menopausal status b | ||||

| Premenopausal | 46 | 40 | ||

| Perimenopausal | 7 | 29 | ||

| Postmenopausal | 1 | 7 | P = 001 | P = 0.0007 |

| Estrogen level (mean) (n = 129) | 0.56 | 0.39 | P = 0.066 | |

| 0.0–0.13 | 5 | 27 | ||

| 0.13–0.28 | 11 | 20 | ||

| 0.28–0.58 | 21 | 12 | ||

| ≥0.58 | 17 | 16 | P = 0.001 | P = 0.0005 |

Results according to primary treatment and potential predictors, including univariate and Kaplan–Meier analysis of failure in subgroups. Means/numbers and significance levels in univariate Student's t‐test, chi‐square test, and LogRank test in Kaplan–Meier analysis of survival in subgroups. Analyses of continuous variables are presented in italics.

WHO classification for endometrial hyperplasia is modified and defined as three different groups: SH, simple hyperplasia; CH, complex hyperplasia; AH, atypical hyperplasia.1, 12

Menopausal status is defined according to levels of estradiol and follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH), assessed before the start of therapy.

Table 2.

Proportional hazard regression analysis evaluating independent variables added to the therapy regimen, with model significance and significance of the added variable

| Independent variable | Hazard ratio | Confidence interval | Model significance | Added variable significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapy regimen | ||||

| LNG‐IUS | Ref. | |||

| MPA cyclic | 0.75 | 0.37–1.50 | ||

| MPA continuous | 0.99 | 0.54–1.80 | P = 0.66 | |

| Age | ||||

| ≤43 years | Ref. | |||

| 44–48 years | 0.92 | 0.47–1.83 | ||

| 49–51 years | 0.80 | 0.40–1.62 | ||

| ≥52 years | 0.36 | 0.15–0.87 | P = 0.18 | P = 0.08 |

| WHO a | ||||

| SH | Ref. | |||

| CH | 1.22 | 0.52–2.89 | ||

| AH | 2.17 | 0.79–6.01 | P = 0.46 | P = 0.25 |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | Ref. | |||

| 1 | 0.51 | 0.13–2.05 | ||

| 2 | 1.69 | 0.70–4.09 | ||

| 3+ | 1.03 | 0.41–2.59 | P = 0.20 | P = 0.09 |

| BMI (n = 133) | ||||

| ≤22 | Ref. | |||

| 23–25 | 1.80 | 0.84–3.87 | ||

| 26–30 | 1.69 | 0.79–3.63 | ||

| ≥30 | 1.27 | 0.57–2.82 | P = 0.56 | P = 0.40 |

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Premenopausal | Ref. | |||

| Perimenopausal | 0.29 | 0.13–0.65 | ||

| Postmenopausal | 0.19 | 0.026–1.37 | P = 0030 | P = 0.0005 |

| Estrogen level (n = 129) | ||||

| 0.0–0.13 | Ref. | |||

| 0.13–0.28 | 2.36 | 0.87–6.40 | ||

| 0.28–0.58 | 4.97 | 2.0–12.4 | ||

| ≥0.58+ | 3.98 | 1.56–10.1 | P = 0.0033 | P = 0.0007 |

Secondary therapy for relapse was not described in the protocol, and such treatment decisions were left to the participating gynaecologists. Ultimately, nine of these women were treated with the LNG‐IUS and three were treated with cyclic MPA (10 mg per cycle for 3 months). The control investigation performed after 24 months showed normal proliferative or atrophic endometrium on microscopy. Among the 36 women who had no further therapy after relapse, 20 had normal proliferative or atrophic endometrium by control investigation performed after 24 months, and 16 women had persistent hyperplasia (CH or SH). Hysterectomy was performed in seven of these women. In the hysterectomy specimens, five of these women had CH and two had AH. No carcinomas were diagnosed in any of the women during the 2 years of follow‐up.

The 18 women who did not respond to the primary therapy after 6 months were also followed up as a separate group over 24 months.7 Ten of these 18 women were treated (six with the LNG‐IUS and four with cyclic MPA), and at 24 months all 10 women had histologically normal endometrium. Five of the 18 women without a response to the primary therapy had persistent hyperplasia after 24 months of follow‐up; three of these women underwent hysterectomy, two had CH, and one had AH. None of the women developed endometrial cancer during the 2 years of follow‐up. Three of the 18 women had spontaneous regression without having received further therapy.

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first randomised multicentre study to report the relapse rate of endometrial hyperplasia after an initial therapy response with complete regression of disease. Although the LNG‐IUS proved to be superior to oral therapy for women with endometrial hyperplasia without atypia,7 no difference existed between the three therapy groups with regard to the risk of relapse after the discontinuation of primary therapy.

Thus, in the present study of 135 women with a response to primary therapy, relapse occurred in 41% of women during the 24‐month follow‐up period. Correspondingly, a recent cohort study with 5 years of follow‐up reported that 30.7% of women with hyperplasia had relapse after oral progestogen was given for 3–12 months.3 Relapse occurred sooner after oral therapy, compared with LNG‐IUS therapy, and only 13.7% of women treated with LNG‐IUS had a relapse;3 however, in that study the LNG‐IUS was left in situ for 5 years,3 contrasting with our RCT where the LNG‐IUS was removed at 6 months. Thus, the sustained dose of progestogen over a longer treatment time may explain their more favourable results.3 A pooled relapse rate of 26% after initial regression has also been estimated in meta‐analyses comparing all existing high‐quality studies of oral and LNG‐IUS therapy. This meta‐analysis included 13 different studies with a total of 126 women.2

The optimal follow‐up time is not well described in the literature, and strategies and guidelines for clinical management after successful therapy for endometrial hyperplasia are scarce. Among women with relapse in the present study, 64% of relapses occurred during the first 6 months of the follow‐up period, although further relapses were diagnosed every 6 months during the follow‐up period (Figures 1 and 2). Gallos and colleagues reported relapses that occurred up to 48 months after oral therapy.3 In LNG‐IUS users, relapses were also diagnosed up to 5 years after therapy withdrawal.3 Even higher relapse rates after the initial response were described in a cohort study from northern Norway that reported a 40% relapse rate after oral therapy and a 27% relapse rate after using the LNG‐IUS, occurring 58–107 months after the cessation of treatment.5 Thus, endometrial surveillance should be continued after the initial regression of the disease, but for which patients and for how long remains unclear.

Few studies have considered predictive factors for the relapse of endometrial hyperplasia after therapy. Our study demonstrated that menopausal status was an independent prognostic factor for relapse in a multivariable analysis, and that estrogen level was also of importance. In a recent cohort study, a body mass index (BMI) of 35 or higher was shown to be an independent prognostic factor that was strongly associated with the failure of endometrial hyperplasia to regress, and it was also associated with an increased tendency to relapse.9 The connection between obesity, elevated estrogen levels, and increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer is well known.12 Approximately half of the women in our study were slightly overweight, but BMI was not a significant prognostic factor for relapse.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include its design: a multicentre RCT comparing relapse after withdrawal of LNG‐IUS and oral progestogen performed according to the standards of the CONSORT criteria. Furthermore, no women were lost to follow‐up. The three initial treatment groups were equally sized and well balanced, and the variables investigated were evenly distributed among the participants. Investigators and pathologists were blinded to treatment allocation. Our RCT was powered on histological regression of endometrial hyperplasia according to the WHO 94 classification after 6 months of progestogen treatment, and not according to rates of disease relapse. Thus our follow‐up study is underpowered: a simplified calculation based upon our sample size shows that a difference in relapse rate of about 30% between the two treatment groups would reach a power of about 80%.

One main weakness of our study was the long inclusion period of the patients, which lasted for nearly 6 years and was partly the result of strict inclusion criteria. As shown in Figure 1, many patients were not eligible for the study, most often because of the poor quality of endometrial biopsy material, which was unsuitable for light microscopy or morphometry. The high number of participating centres recruiting patients may have resulted in differences in the questioning of the patients and in the routine reporting of adverse effects, although the study procedures were described in detail in the protocol. It is open to discussion whether such variations might have impaired the validity of the results. The different age distributions is another limitation of this study.7 The data demonstrate that a proportionally low fraction of the patients were older than 52 years or were postmenopausal, and differences in the response linked with hormonal status were not considered. No interim analyses were performed during the inclusion period to avoid bias because the first patients included in the study had completed their treatment before the last patients were included.

Interpretation

To our knowledge this is the first multicentre RCT to compare histological relapse between the initial 6 months of therapy with the LNG‐IUS and oral progestogen for endometrial hyperplasia. Our trial showed that the LNG‐IUS is superior for inducing histological regression after 6 months of therapy;7 however, the current follow‐up study has shown that when therapy was withdrawn, no differences in the rates of relapse between treatment groups were observed, but overall relapse rates were high, at 41%. Most relapses occurred during the first 6 months after withdrawal of therapy, but relapses were observed during the entire 24‐month observational period.

Conclusion

The risk of histological relapse of non‐atypical endometrial hyperplasia is high within 24 months of ceasing therapy with either the LNG‐IUS or oral MPA. Continued endometrial surveillance and prolonging progestogen therapy should be considered.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests available to view online as supporting information.

Contributions to authorship

All of the authors were involved in the planning and design of the study. All of the authors contributed to the writing of the report and can confirm the accuracy and completeness of the data reported. After completion of the study, all of the authors had full access to all of the results.

Details of ethics approval

The trial was conducted in accordance with national law and local regulations. We had permission from The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics (P REK NORD 25/2004). Permission from the Medicines Agency (Statens Legemiddelverk, SLV) was granted on 13 May 2005. Permission from the National Privacy Protection Committee was granted on 18 March 2004. The Norwegian System of Compensation to Patients also insured each participating woman.

Funding

We are grateful to the institutions who financed the present study. From 2005 to 2011, a research grant given by the Norwegian Cancer Association, the Regional Research Board of Northern Norway (Helse Nord), and the Bank of North Norway funded the study. Annual funding was also granted from the University of Tromsø.

Supporting information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following gynaecologists who contributed patients to this study: Senior Resident Christine Hancke, MD, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, University Hospital North Norway, Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway; Chief Physician Hans Krogstad, MD, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, University Hospital North Norway, Harstad, Norway; Chief Physician Kristen Olav Lind, MD, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Hospital of Nordland, Stokmarknes Hospital, Stokmarknes, Norway; Chief Physician Kevin Sunde Oppegaard, MD, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Hospital of Finnmark, Hammerfest, Hammerfest, Norway; Chief Physician Hemma Hegnauer, MD, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Hospital of Nordland, Bodø, Norway; Researcher Louise Reinertsen, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, St Olavs Hospital, Trondheim, Norway; Chief Physician Gunn Fallås Dahl, MD, Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Oslo, University Hospital‐Ullevål and Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; Chief Physician Hans Skjelle, MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Akershus University Hospital, Lørenskog, Norway; Chief Physician Jacob Nakling, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Innlandet Hospital HF, Lillehammer, Lillehammer, Norway. We are also grateful to the following specialists in private practice: Gynaecologist Kari Anne Trosterud, Elverum, Norway; Gynaecologist Louise Silfverskiöld, Oslo, Norway; Gynaecologist Fredrik Hancke, Oslo, Norway; Gynaecologist Randi Akerøy Lundgren, Lillestrøm, Norway; Gynaecologist Grete Riis‐Johannessen, Kolbotn, Norway; Gynaecologist Finn Forsdahl and Gynaecologist Nils Sørheim, Tromsø, Norway; Gynaecologist Pia Christina Sillanpââ, Moelv, Norway; Gynaecologist Berit Aune, Tromsø, Norway. We are also grateful to the engineers who performed the D–score analyses: Inger Pettersen, Karin Hanssen, Bjørn TG Moe, and Kurt Larsen in the Laboratory of Morphometry at the Department of Clinical Pathology, University Hospital of North Norway. We thank Advisor Dag Grønvoll, Clinical Research Centre and University Hospital of North Norway, who thoroughly monitored all of the data for this study. We thank Roy A. Lysaa, MSc, PhD, for producing the artwork.

Ørbo A, Arnes M, Vereide AB, Straume B. Relapse risk of endometrial hyperplasia after treatment with the levonorgestrel‐impregnated intrauterine system or oral progestogens. BJOG 2016;123:1512–1519.

Linked article This article is commented on by ID Gallos. To view this mini commentary visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13966.

The copyright line for this article was changed on 19 December 2016 after original online publication.

References

- 1. Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long‐term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer 1985;56:403–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gallos ID, Shehmar M, Thangaratinam S, Papapostolou TK, Coomarasamy A, Gupta JK. Oral progestogens vs levonorgestrel‐releasing intrauterine system for endometrial hyperplasia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:547.e1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gallos ID, Krishan P, Shehmar M, Ganesan R, Gupta JK. LNG‐IUS versus oral progestogen treatment for endometrial hyperplasia: a long‐term comparative cohort study. Hum Reprod 2013;28:2966–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vereide AB, Arnes M, Straume B, Maltau JM, Ørbo A. Nuclear morphometric changes and therapy monitoring in patients with endometrial hyperplasia: a study comparing effects of intrauterine levonorgestrel and systemic medroxyprogesterone. Gynecol Oncol 2003;91:526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ørbo A, Arnes M, Hancke C, Vereide AB, Pettersen I, Larsen K. Treatment results of endometrial hyperplasia after prospective D‐score classification: a follow‐up study comparing effect of LNG‐IUD and oral progestins versus observation only. Gynecol Oncol 2008;111:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abu Hashim H, Zayed A, Ghayaty E, El Rakhawy M. LNG‐IUS treatment of non‐atypical endometrial hyperplasia in perimenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. J Gynecol Oncol 2013;24:128–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Orbo A, Vereide A, Arnes M, Pettersen I, Straume B. Levonorgestrel‐impregnated intrauterine device as treatment for endometrial hyperplasia: a national multicentre randomised trial. BJOG 2014;121:477–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferenczy A, Gelfand M. The biologic significance of cytologic atypia in progestogen‐treated endometrial hyperplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;160:126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gallos ID, Ganesan R, Gupta JK. Prediction of regression and relapse of endometrial hyperplasia with conservative therapy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:1165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park JY, Lee SH, Seong SJ, Kim DY, Kim TJ, Kim JW, et al. Progestin re‐treatment in patients with recurrent endometrial adenocarcinoma after successful fertility‐sparing management using progestin. Gynecol Oncol 2013;129:7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Med 2010;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1741‐7015‐8‐18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Webb PM. Obesity and gynecologic cancer etiology and survival. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2013;33:e22–e28. doi: 10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials