Leishmaniasis is caused by protozoan parasites belonging to the genus Leishmania.1,2 The infection is transmitted by phlebotomine sandflies, and a wide range of domestic and wild vertebrates and humans serve as reservoirs of infection. Leishmaniasis is endemic throughout the Middle East, north Africa, parts of Europe, and central and South America.1,2 The worldwide prevalence is 12 million, with a tenth of the world's population at risk.

The infecting Leishmania species determines the clinical presentation of disease, of which there are three dominant clinical forms: cutaneous leishmaniasis, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL), and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Mucocutaneous disease is a chronic inflammatory process involving the nasal, pharyngeal, and laryngeal mucosa, which can lead to extensive tissue destruction. MCL develops as a complication of cutaneous leishmaniasis, parasites disseminating from the primary cutaneous lesion via lymphatic vessels and blood to reach the upper respiratory tract mucosa. Such metastatic spread more commonly occurs with species belonging to the L viannia subgenus (formerly known as the L braziliensis complex), which are present in tropical forested areas of central and South America.1,2 MCL is estimated to develop as a complication of L viannia cutaneous leishmaniasis in 5-20% of untreated patients living in areas where leishmaniasis is endemic.3

Over the past 20 years, “exotic” foreign travel from the United Kingdom has increased, resulting in more cases of imported tropical infections. Increased awareness of such diseases is important as early recognition and treatment may improve outcome. Here we describe three healthy British travellers who developed MCL after travelling to Latin America. Each was managed jointly at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in London by tropical medicine physicians and otorhinolaryngologists. We emphasise the importance of a history of travel to Latin America in patients presenting with unusual skin lesions or chronic nasopharyngeal symptoms and describe the diagnostic process.

Case reports

Case 1

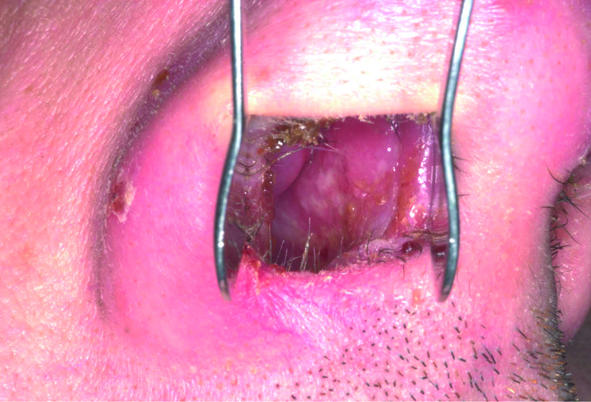

A month after a holiday in South America, a 38 year old man was investigated at a regional centre for infectious and tropical diseases for a persistent cutaneous ulcer on his buttock and associated inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsies failed to establish a diagnosis, and, as the lesion was healing, the patient was discharged. Nine months later, however, the patient developed nasal congestion that persisted for six months until he developed lesions on the exterior of his nose (fig 1, left). Examination of the nasal mucosa showed a granulomatous lesion of the septum (fig 1, centre), and mucosal biopsies were obtained under topical anaesthesia. No parasites were found on microscopy or culture, but DNA of L viannia parasites was detected using polymerase chain reaction, confirming a diagnosis of MCL. He was treated with intravenous sodium stibogluconate and made a full recovery (fig 1, right).

Fig 1.

Patient with mucocutaneous leishmaniasis showing granulomatous lesion of septum (left); lesions on nasal alae (centre); nasal alae after treatment (right)

Case 2

A month after a school trip to Belize, a 17 year old woman developed persistent erythema and swelling of the nasal tip and rhinorrhoea. She was treated as an inpatient at her local hospital with intravenous antibiotics for suspected low grade bacterial cellulitis. After referral to the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, cutaneous and mucosal biopsies were negative on microscopy and culture but polymerase chain reaction was positive for L viannia DNA, establishing a diagnosis of MCL. She was successfully treated with sodium stibogluconate.

Case 3

A 19 year old woman consulted her general practitioner shortly after returning from extensive travels in rural South America, complaining of persistent skin ulcers and nasal congestion. Her doctor contacted the Hospital for Tropical Diseases immediately concerned that her patient might have MCL. A differential diagnosis of Wegener's granulomatosis was considered as the patient was known to have serum antinuclear antibodies. Clinical examination showed florid inflammation of the nasal and oropharyngeal mucosa and five cutaneous ulcers with raised margins. Diagnoses of cutaneous leishmaniasis and MCL were established by positive culture and polymerase chain reaction of mucosal and cutaneous biopsies. She was successfully treated with intravenous sodium stibogluconate.

Discussion

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is reported infrequently among travellers returning from Latin America to countries where the disease is not endemic.4-9 The cases described here were all young healthy travellers who had spent time in tropical forest areas of Latin America; none had any risk factors for HIV infection. MCL is endemic in such areas between southern Mexico and the northern tip of Argentina.2 The trend towards “adventure travel” to Latin America may lead to MCL being more often imported to the United Kingdom. Patients with MCL may present to a wide variety of clinicians, including general practitioners, all of whom should be aware of the potential significance of a history of rural travel in Latin America. Familiarity with the manifestations of cutaneous leishmaniasis and MCL may speed diagnosis and limit disease progression.

Recognition of cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions may help to prevent development of MCL or facilitate diagnosis of established MCL. The disease can be prevented by treating L viannia cutaneous leishmaniasis before mucosal involvement. Alternatively, in patients with established mucosal disease, the presence of cutaneous leishmaniasis (or a history suggestive of a previous self healing cutaneous leishmaniasis lesion) may provide a strong clue to a diagnosis of mucocutaneous disease.

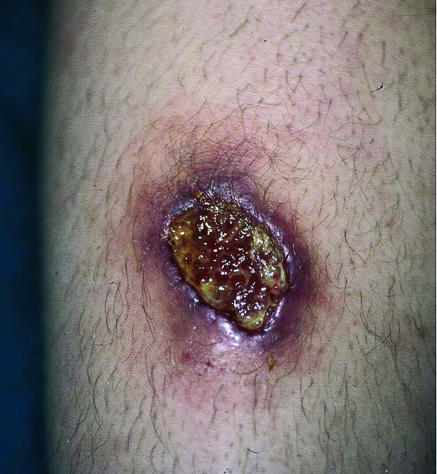

Cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions often develop on exposed parts of the body within a few weeks of exposure to infected sandfly bites. Single or multiple ulcers typically have a raised, indurated margin and a sloughy base (fig 2). There may be satellite lesions (sporotrichoid spread) and cord-like infiltration of proximal lymphatic vessels and local lymphadenopathy.

Fig 2.

A 4 cm diameter cutaneous leishmaniasis ulcer on lower leg caused by L viannia subgenus species showing the typical raised, indurated margin

Box 1: Differential diagnosis for nasal congestion

Rhinitis (allergy)

Anatomical cause (septal deviation, hypertrophic turbinates)

Hormonal disorder (puberty, pregnancy, hypothyroidism, acromegaly)

Granulomatous disease (sarcoidosis, Wegener's granulomatosis)

Drug induced cause (rhinitis medicamentosa, prazosin, cocaine)

Impaction (crusts, foreign body)

Mass (adenoids, nasal polyps, nasopharyngeal carcinoma)

Infection (leishmaniasis, tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, rhinoscleroma, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis)

The differential diagnosis for cutaneous leishmaniasis includes secondary infected insect bites, sporotrichosis (a fungal infection implanted into the skin by a thorn or other penetrating injury), or more rarely cutaneous tuberculosis. Appropriate drug treatment promotes rapid healing of cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions, but the great majority will heal spontaneously over several months; such healing, however, does not preclude the later development of MCL, as illustrated by case 1.

The most common symptom of MCL is persistent nasal congestion, for which the differential diagnosis is broad (box 1). Anterior nasal septal granulomas may be visible with a light source and Thudicum's speculum, whereas posteriorly located granulomas require nasendoscopy to be seen. Progressive MCL lesions destroy upper respiratory tract mucosa over months and years. Common sites are the turbinates and nasal septum,7,9 where erosion of underlying tissue and cartilage may result in perforation. Progressive tissue destruction at the nasal mucocutaneous junction in advanced disease may cause marked disfigurement, requiring reconstructive surgery. Lesions may also affect the palate, pharynx, and larynx, causing palatal dysfunction, dysphagia, dysphonia, and aspiration.1,2 Bony structures are not involved.

Diagnoses of cutaneous leishmaniasis and MCL are established by demonstrating the presence of Leishmania parasites in infected tissues. Serology is rarely helpful except in advanced MCL. Punch biopsies should be taken from the raised, indurated edge of cutaneous leishmaniasis lesions and sent fresh for microbiological and parasitological examination and in formalin for histopathological assessment. Examination of Giemsa stained impression smears for the presence of the intracellular form of the parasites (amastigotes) may quickly yield a diagnosis in some patients. Amastigotes may also be seen in histopathological sections. The flagellate form of the parasite (promastigote) may be cultured from biopsies on modified Novy-McNeal-Nicolle medium incubated for up to three weeks.

Polymerase chain reaction is the most sensitive diagnostic test, however, and is also used to differentiate L viannia subgenus infections, which are associated with the greatest risk of MCL.10,11 Similarly, in patients with suspected MCL, biopsies of mucosal lesions are required for diagnosis, and additional biopsies may be taken from the turbinates even if these are not overtly involved. Histopathology of mucosal biopsies shows granulomatous changes for which the differential diagnosis is broad (box 2). Compared with cutaneous leishmaniasis, Leishmania parasites are less readily visualised or cultured from MCL lesions because the vigorous host response limits the tissue parasite burden. In recent years, however, polymerase chain reaction has proved to be a sensitive tool.11

Box 2: Differential diagnosis for nasal granulomas

Bacterial infection (tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, rhinoscleroma)

Fungal infection (coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, rhinosporidiosis)

Parasitic infection (leishmaniasis)

Autoimmune (Wegener's granulomatosis, systemic lupus erythematosis)

Sarcoidosis

Lymphoma

Foreign body

Heavy metals (beryllium, nickel)

Idiopathic cause

MCL requires prolonged parenteral treatment with pentavalent antimonials (treatment of choice) or amphotericin preparations. Such treatment is associated with toxicity and risk of relapse.1,2 Patients require joint management from infectious or tropical diseases physicians plus otorhinolaryngologists who have clinical experience of MCL and access to the necessary specialist laboratory investigations. Expeditious and appropriate care, however, can be given only after the diagnosis has been suspected.

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis may be acquired by travellers to central and South America

Contributors: SA helped to collect patients' data and to write the manuscript. SDL provided medical care for the patients, collected patients' data, and wrote the manuscript. JK and HG provided otorhinolaryngology assessments and contributed to the manuscript. DNJL was responsible for the care of the patients and contributed to the manuscript. DNJL is the guarantor.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Herwaldt BL. Leishmaniasis. Lancet 1999;354: 1191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dedet JP, Pratlong F. Leishmaniasis. In: Cook GC, Zumla A, eds. Manson's tropical diseases. 21st ed. London: Saunders, 2003: 1339-64.

- 3.David C, Dimier-David L, Vargas F, Torrez M, Dedet JP. Fifteen years of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in Bolivia: a retrospective study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1993;87: 7-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosbotham JL, Corbett EL, Grant HR, Hay RJ, Bryceson AD. Imported mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996;21: 288-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scope A, Trau H, Bakon M, Yarom N, Nasereddin A, Schwartz E. Imported mucosal leishmaniasis in a traveler. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37: e83-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa JW Jr, Milner DA Jr, Maguire JH. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in a US citizen. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2003;96: 573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lohuis PJ, Lipovsky MM, Hoepelman AI, Hordijk GJ, Huizing EH. Leishmania braziliensis presenting as a granulomatous lesion of the nasal septum mucosa. J Laryngol Otol 1997;111: 973-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singer C, Armstrong D, Jones TC, Spiro RH. Imported mucocutaneous leishmaniasis in New York city. Report of a patient treated with amphotericin B. Am J Med 1975;59: 444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galioto P, Fornaro V. A case of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Ear Nose Throat J 2002;81: 46-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Bruijin MHL, Barker DC. Diagnosis of New World leishmaniasis: specific detection of species of the Leishmania braziliensis complex by amplification of kinetoplast DNA. Acta Tropica 1992;52: 45-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pirmez C, da Silva Trajano V, Paes-Oliveira Neto M, da-Cruz AM, Goncalves-da-Costa SC, Catanho M, et al. Use of PCR in diagnosis of human American tegumentary leishmaniasis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Clin Microbiol 1999;37: 1819-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]