Abstract

Rapid antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) would decrease misuse and overuse of antibiotics. The “holy grail” of AST is a phenotype-based test that can be performed within a doctor visit. Such a test requires the ability to determine a pathogen’s susceptibility after only a short antibiotic exposure. Herein, digital PCR (dPCR) was employed to test whether measuring DNA replication of the target pathogen through digital single-molecule counting would shorten the required time of antibiotic exposure. Partitioning bacterial chromosomal DNA into many small volumes during dPCR enabled AST results after short exposure times by 1) precise quantification and 2) a measurement of how antibiotics affect the states of macromolecular assembly of bacterial chromosomes. This digital AST (dAST) determined susceptibility of clinical isolates from urinary tract infections (UTIs) after 15 min of exposure for all four antibiotic classes relevant to UTIs. This work lays the foundation to develop a rapid, point-of-care AST and strengthen global antibiotic stewardship.

Keywords: antibiotics, DNA, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, digital PCR, chromosome segregation

Graphical Abstract

Digital counting reveals antibiotic susceptibility: Single molecule counting detects subtle changes in the amount and the assembly state of bacterial chromosomes after short exposure of live bacteria to antibiotics.

The increasingly liberal use and misuse of antibiotics (ABX) has led to widespread development of antibiotic resistance.[1] To address this crisis, we need rapid and reliable tests of a pathogen’s susceptibility to the drugs available (antimicrobial susceptibility test, AST) to provide correct, life-saving treatment, facilitate antibiotic stewardship[2] and drastically decrease hospital costs.[1a,3] Having a rapid AST that provides results within the period of a doctor visit would lead to improved patient outcomes and reduced spread of antibiotic resistance.[4] Development of a rapid AST is currently the focus of significant research efforts[5] that aim to supplant traditional clinical methods. To reduce the spread of resistance, one urgently needed AST is for urinary tract infections (UTIs), which are among the most common bacterial infections, yet can progress to pyelonephritis or sepsis.[6]

Two types of ASTs are currently used in clinical settings: traditional culture-based methods and genotypic methods. Culture-based tests remain the gold standard for determining antibiotic susceptibility because they detect phenotypic susceptibility to a drug, however these tests require a long period of antibiotic exposure (typically 16–24 h).[7] We[8] and others[5a,5b,5k,9] have proposed using confinement of single, or a small number of, bacterial cells in small volumes to reduce the duration of antibiotic exposure required to read out the phenotype of the target pathogen. However, these methods typically do not differentiate between the pathogen and the potential contamination of the sample with commensal bacteria. Alternative genotypic methods (detecting genes responsible for known mechanisms of resistance) are more rapid than culture-based approaches.[10] However, these resistance genes constitute only a fraction of all possible mechanisms of resistance,[11] and new forms of resistance evolve quickly.[12] Therefore, predicting resistance by analyzing a few known resistance genes is not a general solution.[13]

To develop more rapid and specific phenotypic tests, hybrid approaches have been proposed that use quantification of nucleic acids to determine the susceptibility or resistance phenotype after a short antibiotic exposure. These tests do not rely on detecting specific resistance genes.[5g,5i] For example, quantification of RNA has allowed determination of susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (cip) and rifampin,[5i] which impair transcription, after exposures as short as 15 min. However, these methods require longer incubation times when using antibiotics with different mechanisms of action. Using quantitative PCR (qPCR), quantification of DNA after 2–9 h of antibiotic exposure was used to detect bacterial growth and determine susceptibility,[5d,5e] however an ideal exposure time would be shorter than one cell division.

Here we tested the hypothesis that digital methods of nucleic acid quantification,[14] such as digital PCR (dPCR), would enable use of DNA markers to perform a phenotypic AST after short antibiotic exposure. Digital methods partition bacterial chromosomal DNA into thousands of compartments and then use targeted amplification to determine the number of “positive” compartments containing DNA carrying one or more copies of the target gene. This partitioning should enable more precise and robust measurements of concentrations of bacterial DNA, achieving higher statistical power with fewer replicates relative to qPCR.[14c,15] Further, we hypothesized that this partitioning would provide unique capabilities for AST when analyzing target genes present in a macromolecular assembly, such as a bacterial chromosome during replication. In contrast to qPCR, dPCR results should reflect the state of the macromolecular assembly, providing a different count for a pair of segregated chromosomes (two positives) vs the chromosomal assembly just prior to segregation (one positive). We test our hypotheses in the context of four of the main antibiotics used in UTI treatment: ciprofloxacin (cip), nitrofurantoin (nit), sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (sxt), and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (amc).[6a,7b,16]

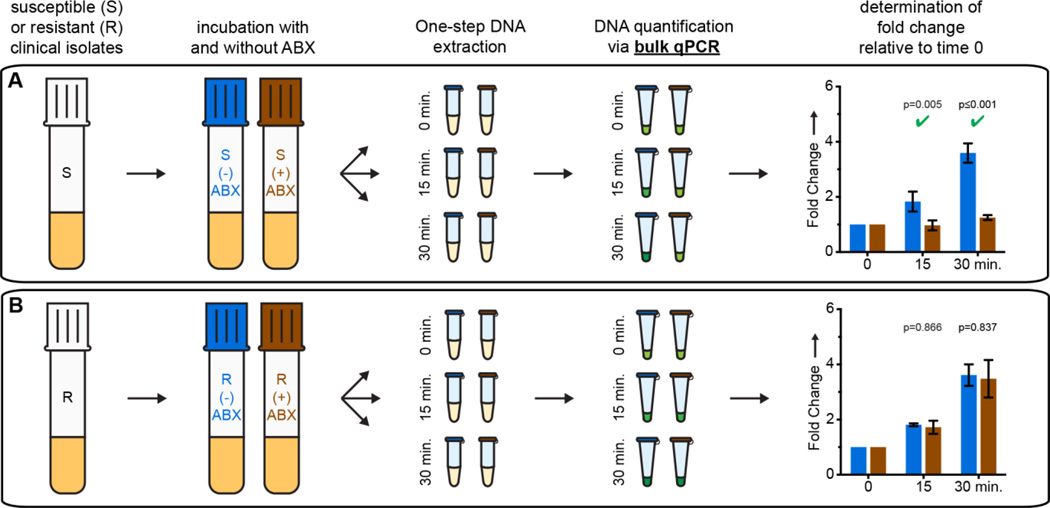

We first determined the minimum antibiotic exposure time necessary to differentiate susceptible and resistant clinical UTI isolates using qPCR analysis of DNA after incubation in the presence (“treated”) or absence (“control”) of antibiotics (see SI). Cycle thresholds were used to calculate the relative fold change in DNA concentration compared to t=0 min (Fig. 1). When treated with cip, DNA replication in susceptible isolates was significantly inhibited, resulting in an increasing difference in fold change between target concentration in treated and control samples. If the isolate was resistant, DNA replication continued regardless of exposure. To align with FDA requirements for very major errors[17] we used a conservative alpha, 0.02 (see SI). Susceptibility to cip could be determined after 15 min of exposure. We obtained similar results using isolates pre-cultured in media and in urine (SI Fig. 1), and chose to conduct all subsequent experiments in media in order to reduce the work with human samples and to ensure reproducibility. The focus of this work is to evaluate the differences in minimum antibiotic exposure time necessary to determine susceptibility when quantification of changes in DNA is performed with qPCR vs dPCR.

Figure 1.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) time course for exposure of A) susceptible (S) and B) resistant (R) UTI E. coli isolates to ciprofloxacin. Fold change values represent changes from t=0 min; error bars represent the upper and lower bounds of the 98% confidence interval (C.I.; see the SI). N=3 where N is the number of technical qPCR replicates. Significant differences (p value ≤ 0.02) are marked with a green check mark.

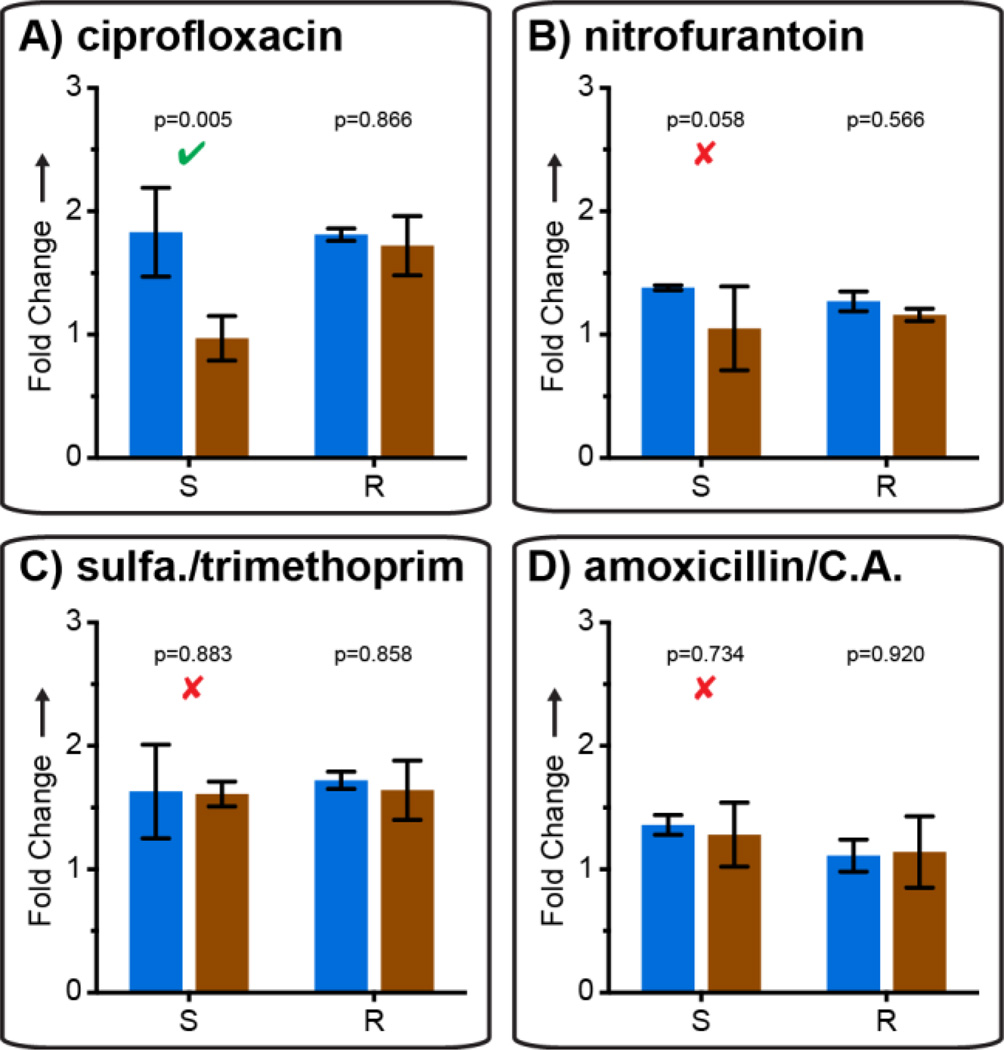

These results are the first evidence of detection of phenotypic susceptibility based on DNA quantification after only 15 min of antibiotic exposure. The rapid effect of cip on DNA replication is logical because the drug’s mechanism of action is to inhibit DNA-gyrase and topoisomerase IV, producing double stranded breaks in DNA and directly inhibiting DNA replication.[18] To test generality, we evaluated AST with three other antibiotics: nit,[19] sxt,[20] and amc (which is not known to specifically affect DNA replication) (see SI). Using qPCR, 15 min of exposure to these three antibiotics was not sufficient to detect a significant difference in DNA replication in susceptible isolates (Fig. 2B–D), while statistically significant differences were detectable with cip treatment (Fig 2A).

Figure 2.

Comparison of susceptible and resistant isolates from UTI samples after a 15 min exposure with each of four antibiotics, analyzed by quantitative PCR. Fold change values represent change from t = 0 min; error bars are 98% C.I. (see SI), N=3. Significant (p-value ≤ 0.02) and nonsignificant differences detected using the susceptible isolate are marked with a green check and red × respectively.

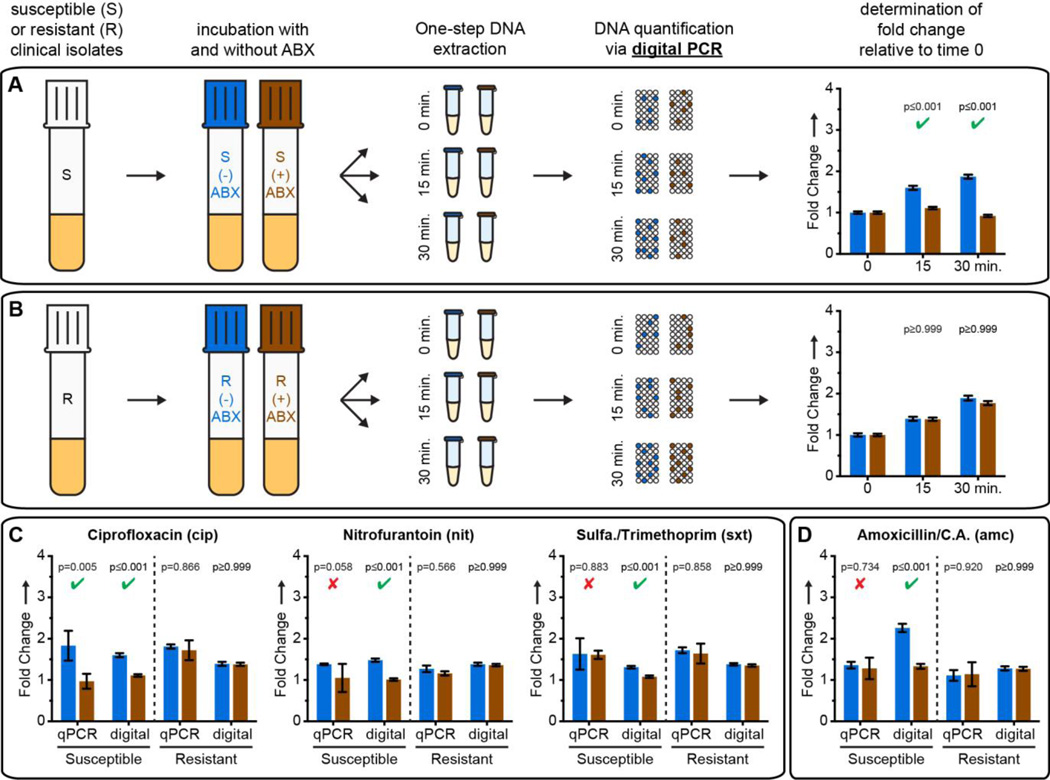

A focus of this work was to evaluate the differences in minimum antibiotic exposure time necessary to determine susceptibility when quantification of changes in DNA is performed with qPCR versus dPCR. Thus, we next tested AST with digital quantification by quantifying the same DNA samples from the qPCR analysis using dPCR (Figure 3). For cip, we detected a more statistically significant difference (smaller p value than in qPCR) between target concentrations in treated and control susceptible isolates (Figure 3A), whereas target concentrations did not differ between treated and control resistant isolates (Figure 3B). A significant difference was also detected after 15 min exposures to nit (Figure 3C) or sxt (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

AST results using dPCR. (A,B) Time course results for exposure of susceptible (A) and resistant (B) UTI E. coli isolates to ciprofloxacin. (C,D) Fold changes after treatment with all four antibiotics tested. Significant (p-value ≤ 0.02) and nonsignificant p-values for susceptible isolates are denoted with a green check and red × respectively. Samples treated with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (D) were extracted using a non-denaturing protocol. Concentrations are calculated using Poisson statistics. Fold change values represent change from t = 0 min; all error bars are 98% C.I. (see SI), N=3 for qPCR, N=2 for dPCR.

Interestingly, neither qPCR or dPCR detected susceptibility after exposure to amc when samples were denatured and treated with protease during extraction (SI Figure 2). This confirmed that genome replication proceeded (resulting in an increase in the total number of amplifiable targets) during incubation with amc regardless of phenotype. We therefore tested the hypothesis that dPCR would be sensitive not only to the total gene copy number, but also to the state of macromolecular assembly of chromosomal DNA. If exposure to amc causes changes in chromosome segregation, even without affecting replication, dPCR should still be able to differentiate susceptible and resistant phenotypes. To preserve chromosome structure and macromolecular complexes, we performed DNA extraction in non-denaturing conditions without protease treatment. Under these conditions, dPCR provided susceptibility phenotype after 15 min of exposure to amc (Figure 3D).

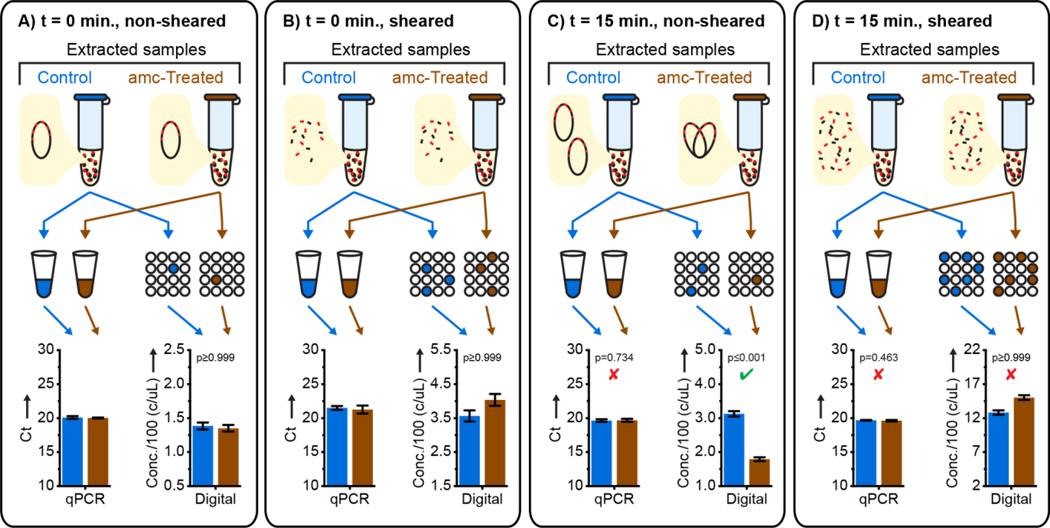

To test whether dPCR differentiated susceptible and resistant isolates via quantifying macromolecular assemblies, we designed control experiments in which all assemblies were sheared into ~1000 bp DNA fragments, much smaller than the average distance between 23S genes within the genome (see SI). As expected, shearing caused an increase in measured target concentration when quantified using dPCR, but not using qPCR (Fig. 4A–B). In samples that were not sheared, dPCR detected the susceptible phenotype after 15 min of amc exposure (Fig. 4C). Shearing these samples to disrupt macromolecular assemblies eliminated the ability to detect susceptibility (Fig. 4D); qPCR measurements confirmed this was not due to loss of DNA. This suggests that in amc-susceptible isolates short exposure to amc does not result in a change of the total number of target gene copies, but does change the macromolecular assembly of these copies.

Figure 4.

A mechanistic investigation of AST by digital PCR (dPCR) after beta lactam exposure and non-denaturing DNA extraction using shearing to disrupt macromolecular assemblies; error bars for qPCR are 2.8 S.D. (see SI), N=3; error bars are 98%C.I. for dPCR (see SI), N=2. Significant (p-value ≤ 0.02) and nonsignificant p-values for susceptible isolates quantified using dPCR are denoted with a green check and red × respectively (see SI).

Our results suggest a previously unknown effect of brief beta-lactam antibiotic exposure: a delay in chromosome segregation. Using dPCR (but not qPCR) this effect can be quantified by counting the number of macromolecular DNA assemblies containing 23S target genes, and used for AST. The high resolution of digital quantification enables measuring small (less than two-fold) changes in chromosome replication and segregation after antibiotic exposure shorter than the average time of cell division. The dAST approach developed here adds chromosome segregation to the list of the phenotypic markers suitable for rapid antibiotic susceptibility detection. The ability to partition macromolecular assemblies allows dAST to be used even when genome replication proceeds on the timescale of antibiotic exposure, while the high precision of digital quantification allows accurate determination of susceptibility after shorter exposure times than would be required using less-precise methods such as qPCR.

These dAST results warrant a follow-up study with a wide range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial isolates from urine, blood, and other sample types, and then a clinical study comparing dAST directly from patient samples to the gold standard culture-based methods. Elucidating the effects of using variable clinical samples with a range of background matrices is a critical next step in the development of a rapid, sample-to-answer AST. Ultimately, a sample-to-answer AST at the point of care must be robust, rapid, and require minimal sample handling and instrumentation. Ideally, such a workflow will integrate sample handling, antibiotic exposure, and quantification into a single device. We anticipate that digital isothermal amplification chemistries will replace dPCR in dAST.[15a,21] When integrated with sample preparation[22] and combined with simple readouts,[23] we envision that digital quantification will establish a new paradigm in rapid point of care AST.

Experimental Section

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by DARPA Cooperative Agreement HR0011-11-2-0006, NIH Grant R01EB012946, and a grant from the Joseph J. Jacobs Institute for Molecular Engineering for Medicine. We thank Janet Hindler and Shelley Miller for advice and experimental assistance. We thank Natasha Shelby for contributions to writing and editing this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Nathan G. Schoepp, Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA, 91125, USA.

Eugenia M. Khorosheva, Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA, 91125, USA.

Travis S. Schlappi, Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA, 91125, USA

Matthew S. Curtis, Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA, 91125, USA

Romney M. Humphries, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, 10888 Le Conte Avenue, Brentwood Annex, Los Angeles, CA, 90095, USA

Janet A. Hindler, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, 10888 Le Conte Avenue, Brentwood Annex, Los Angeles, CA, 90095, USA

Rustem F. Ismagilov, Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA, 91125, USA

References

- 1.a) CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. p. 114. [Google Scholar]; b) Laxminarayan R, et al. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:1057–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White House. National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Washington D.C.: 2015. p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts RR, et al. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1175–1184. doi: 10.1086/605630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spellberg B, et al. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 5):S397–S428. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Besant JD, Sargent EH, Kelley SO. Lab Chip. 2015;15:2799–2807. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00375j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lu Y, Gao J, Zhang DD, Gau V, Liao JC, Wong PK. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:3971–3976. doi: 10.1021/ac4004248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhu C, Yang Q, Liu L, Wang S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50:9607–9610. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Waldeisen JR, Wang T, Mitra D, Lee LP. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28528. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Rolain JM, Mallet MN, Fournier PE, Raoult D. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004;54:538–541. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Mezger A, Gullberg E, Goransson J, Zorzet A, Herthnek D, Tano E, Nilsson M, Andersson DI. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015;53:425–432. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02434-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Mach KE, Mohan R, Baron EJ, Shih MC, Gau V, Wong PK, Liao JC. J. Urol. 2011;185:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Ivančić V, et al. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:1213–1219. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02036-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Halford C, Gonzalez R, Campuzano S, Hu B, Babbitt JT, Liu J, Wang J, Churchill BM, Haake DA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:936–943. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00615-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Barczak AK, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:6217–6222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119540109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Sinn I, Kinnunen P, Albertson T, McNaughton BH, Newton DW, Burns MA, Kopelman R. Lab Chip. 2011;11:2604–2611. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00734j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Mann TS, Mikkelsen SR. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:843–848. doi: 10.1021/ac701829c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m) Tang Y, Zhen L, Liu J, Wu J. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:2787–2794. doi: 10.1021/ac303282j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Hooton TM. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1028–1037. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1104429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wagenlehner FM, Pilatz A, Weidner W. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2011;38 Suppl:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Andrews JM. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001;48(Suppl 1):5–16. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.suppl_1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Seventeenth Informational Supplement. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boedicker JQ, Li L, Kline TR, Ismagilov RF. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1265–1272. doi: 10.1039/b804911d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen CH, Lu Y, Sin ML, Mach KE, Zhang DD, Gau V, Liao JC, Wong PK. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:1012–1019. doi: 10.1021/ac9022764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Beal SG, Ciurca J, Smith G, John J, Lee F, Doern CD, Gander RM. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:3988–3992. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01889-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Altun O, Almuhayawi M, Ullberg M, Özenci V. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:4130–4136. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01835-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Blaschke AJ, et al. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;74:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Spanu T, et al. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:2783–2785. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00284-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Kostic T, Ellis M, Williams MR, Stedtfeld TM, Kaneene JB, Stedtfeld RD, Hashsham SA. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;99:7711–7722. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6774-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Walsh C. Nature. 2000;406:775. doi: 10.1038/35021219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Webber MA, Piddock LJV. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003;51:9–11. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cirz RT, Chin JK, Andes DR, de Crecy-Lagard V, Craig WA, Romesberg FE. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Tuite N, Reddington K, Barry T, Zumla A, Enne V. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014;69:1729–1733. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pulido MR, Garcia-Quintanilla M, Martin-Pena R, Cisneros JM, McConnell MJ. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013;68:2710–2717. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Baker M. Nature Methods. 2012;9:541–544. [Google Scholar]; b) Huggett JF, et al. Clin. Chem. 2013;59:892–902. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.206375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Whale AS, Huggett JF, Cowen S, Speirs V, Shaw J, Ellison S, Foy CA, Scott DJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e82. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Selck DA, Karymov MA, Sun B, Ismagilov RF. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:11129–11136. doi: 10.1021/ac4030413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:9236–9241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Weaver S, Dube S, Mir A, Qin J, Sun G, Ramakrishnan R, Jones RC, Livak KJ. Methods. 2010;50:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta K, et al. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011;52:e103–e120. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.FDA. Class II Special Controls Guidance Document: Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test (AST) Systems. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fàbrega A, Madurga S, Giralt E, Vila J. Microb Biotech. 2009;2:40–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2008.00063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guay DR. Drugs. 2001;61:353–364. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masters PA, O'Bryan TA, Zurlo J, Miller DQ, Joshi N. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003;163:402–410. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Gansen A, Herrick AM, Dimov IK, Lee LP, Chiu DT. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2247–2254. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21247a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jarvius J, Melin J, Goransson J, Stenberg J, Fredriksson S, Gonzalez-Rey C, Bertilsson S, Nilsson M. Nature Methods. 2006;3:725–727. doi: 10.1038/nmeth916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Shen F, Davydova EK, Du W, Kreutz JE, Piepenburg O, Ismagilov RF. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:3533–3540. doi: 10.1021/ac200247e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sun B, Rodriguez-Manzano J, Selck DA, Khorosheva E, Karymov MA, Ismagilov RF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:8088–8092. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buser JR, Wollen A, Heiniger EK, Byrnes SA, Kauffman PC, Ladd PD, Yager P. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1994–1997. doi: 10.1039/c5lc00080g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodriguez-Manzano J, Karymov MA, Begolo S, Selck DA, Zhukov DV, Jue E, Ismagilov RF. ACS Nano. 2016;10:3102–3113. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.