Abstract

Zika virus (ZIKV) is currently undergoing pandemic emergence. While disease is typically subclinical, severe neurologic manifestations in fetuses and newborns after congenital infection underscore an urgent need for antiviral interventions. The adenosine analog BCX4430 has broad-spectrum activity against a wide range of RNA viruses, including potent in vivo activity against yellow fever, Marburg and Ebola viruses. We tested this compound against African and Asian lineage ZIKV in cytopathic effect inhibition and virus yield reduction assays in various cell lines. To further evaluate the efficacy in a relevant animal model, we developed a mouse model of severe ZIKV infection, which recapitulates various human disease manifestations including peripheral virus replication, conjunctivitis, encephalitis and myelitis. Time-course quantification of viral RNA accumulation demonstrated robust viral replication in several relevant tissues, including high and persistent viral loads observed in the brain and testis. The presence of viral RNA in various tissues was confirmed by an infectious culture assay as well as immunohistochemical staining of tissue sections. Treatment of ZIKV-infected mice with BCX4430 significantly improved outcome even when treatment was initiated during the peak of viremia. The demonstration of potent activity of BCX4430 against ZIKV in a lethal mouse model warrant its continued clinical development.

Keywords: Zika virus, ZIKV, AG129 mice, antiviral, BCX4430, ribavirin, flavivirus

1. Introduction

Zika virus (ZIKV) is an emerging mosquito-borne flavivirus that typically results in either subclinical infection or a mild disease characterized by headache, conjunctivitis, fever, rash and arthralgia (Gatherer and Kohl, 2015; Ramos da Silva and Gao, 2016). ZIKV is rapidly spreading throughout the Americas, infecting millions of people in many different countries. More serious illness, including congenital neurologic syndromes and severe Guillain-Barre syndrome, has been associated with recent ZIKV outbreaks (Araujo et al., 2016; Lazear and Diamond, 2016). Microcephaly appears to be the most dramatic and severe outcome among a spectrum of congenital ZIKV infection neurologic deficits that are associated with ZIKV infection during pregnancy (Costa et al., 2016; de Fatima Vasco Aragao et al., 2016). In cases of congenital microcephaly, ZIKV has been detected in the placenta, amniotic fluid, cerebrospinal fluid and fetal brain tissue (Cordeiro et al., 2016; Driggers et al., 2016; Mlakar et al., 2016; Noronha et al., 2016) and there is little doubt that ZIKV infection during pregnancy can result in profound neurologic damage to the fetus (Rasmussen et al., 2016). The World Health Organization has concluded that ZIKV infections constitute a public health emergency of international concern. Countermeasures for the treatment or prevention of ZIKV disease are desperately needed. Developing an antiviral drug for treatment during pregnancy presents substantial challenges arising from justified concerns for the wellbeing of the mother and her developing fetus. Several precedents exist for treatment during pregnancy in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) field (Brocklehurst and Volmink, 2002). In addition to the obvious desirability of safe and effective treatment of ZIKV infection in pregnant women, men shedding infectious ZIKV in semen have the potential to transmit the virus to their sexual partners and represent another high-priority target population for effective interventions. Patients experiencing Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) are another target group for the development of antiviral interventions (Dirlikov et al., 2016), although virus involvement in GBS remains to be determined.

The small molecule drug candidate BCX4430 is an adenosine nucleoside analog that functions as a selective inhibitor of viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Warren et al., 2014) that is currently in clinical stage development. Broad-spectrum activity against various RNA viruses in cell culture has been reported (Warren et al., 2014). BCX4430 is highly active in a hamster model of yellow fever virus (YFV) disease, with efficacy demonstrated even when administered once viremia and hepatitis were established (Julander et al., 2014). Potent activity has also been reported in a mouse models of Ebola (EBOV) and Marburg virus (MARV) diseases, and a lethal non-human primate model of MARV disease (Warren et al., 2014). Because of its broad-spectrum activity and efficacy against a related flavivirus, YFV, BCX4430 was investigated for antiviral efficacy against ZIKV.

Various mouse models have been developed for the study of ZIKV infection (Aliota et al., 2016; Dowall et al., 2016; Lazear et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Miner et al., 2016; Rossi et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Zmurko et al., 2016). Because wild-type mice typically clear ZIKV rapidly following inoculation and do not develop serious illness, many researchers have employed various mouse strains lacking type 1 interferon (IFN) function. The IFN regulatory system is critical for resistance to ZIKV infection in mice and differential disease severity was observed when IFN receptors were removed or blocked (Lazear et al., 2016; Yockey et al., 2016). The importance of the IFN pathway was further delineated when ZIKV-infected SCID mice, lacking T and B lymphocytes, were shown to have an extended survival time (average of 26 days longer) as compared with IFN-receptor deficient mice (Zmurko et al., 2016). Mice that lack type I and II IFN receptors (AG129 mice) are highly susceptible to ZIKV infection and display relevant signs of disease (Zmurko et al., 2016).

We describe herein the activity of BCX4430 in both cell culture and an AG129 mouse model of ZIKV infection characterized by viral encephalomyelitis. These data provide proof-of-principle for the use of BCX4430 in the treatment of ZIKV and justification for the further development of this nucleoside analog.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Animals

Male and female AG129 mice, lacking IFN-α/β and -μ receptors, were bred under germ-free conditions in an in-house breeding colony. Mice between 8 and 10 weeks with an average weight of 22 g were used. Animals were assigned to groups and individually marked with ear tags.

2.2 Test articles

BCX4430 dihydrochloride was supplied as a powder by BioCryst Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Treatment doses reported herein represent the concentration of the dihydrochloride, which contains 64% BCX4430. Ribavirin was provided by the former ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Compounds were prepared in minimal essential medium (MEM) or sterile saline for cell culture and animal studies, respectively.

2.3 Viruses

The MR-766 isolate of ZIKV was collected from a sentinel rhesus monkey in the Zika forest of Uganda in April 1947 and the P 6-740 strain was collected from mosquitos in Malaysia in July 1966. These two ZIKV strains were provided by Robert B. Tesh (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX). The ZIKV PRVABC-59 strain was isolated in Puerto Rico from the blood of a human patient in December 2015. The virus was provided by Barbara Johnson (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, CO). Virus strains were amplified once or twice in Vero76 cells and had titers of 107.7, 106.7 and 107.5 50% cell culture infectious doses (CCID50)/mL for MR-766, P 6-740 and PRVABC-59, respectively. The Malaysian P 6-740 strain was titrated for lethality in AG129 mice and used for the present animal study.

2.4 In vitro evaluation of compounds

The antiviral activity of BCX4430 and ribavirin were evaluated in vitro by cytopathic effect (CPE) inhibition assays. Various cell lines, including Vero76, Huh7 and RD, were used for evaluation of antiviral effects. Compounds were prepared in MEM just prior to testing. Inhibition of virus replication was determined by microscopic examination of the infected cells for cytopathic effect, increase of neutral red (NR) dye uptake (colorimetric determination), and virus yield reduction. Uninfected cells treated with a compound were assayed as above for cytotoxicity control.

2.5 Real-time RT-PCR for the detection of ZIKV RNA

Fifty to 100 mg of freshly isolated tissue was ground with a pestle in 1 mL TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and total RNA was extracted. For the extraction of viral RNA from serum, QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Spin kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Extracted RNA was eluted with nuclease-free water and was amplified by a quantitative real-time RT-PCR using the Logix Smart Zika Test developed by Co-Diagnostics, Inc. (Bountiful, UT). Five μL of the master mix containing a set of primers and Rapid Probe, labeled with a FAM fluorophore and DABCYL quencher, was mixed with 2-5 μL of RNA and an appropriate volume of water for a final reaction volume of 10 μl. RNA was first reverse transcribed for 10 minutes at 55°C, followed by strand separation by heating to 95°C fo r 20 seconds. The PCR reaction consisted of 40 cycles at 95°C for 1 secon d and 55°C for 20 seconds. A standard curve was generated with a synthetic RNA spanning the region of amplification and it was used to calculate the number of genome equivalents of the unknown samples.

2.6 Infectious assay

Freshly isolated tissues were homogenized in 1:3 (wt/vol) of MEM in a Stomacher bag and stored at −80°C. A 1:10 starting dilution was made and serial dilutions were then prepared and added to a 96-well cell culture dish seeded for 90% confluency with Vero cells. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 5 days and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich). Immunohistochemistry was performed using an anti-flavivirus group antigen antibody (EMD Millipore, Temecula, CA) as described below.

2.7 Immunohistochemistry

Two to 4 pups from each litter were prepared for histology and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Whole pups with placentas were placed in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde. Twenty-four hours later the tissues were rinsed once in phosphate-buffered saline and placed in 70% ethanol. Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned (5-8 μm) and processed for hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining and IHC. Following de-parafinization, the sections were blocked with normal goat serum for 60 minutes at room temperature. Either a rabbit anti-ZIKV polyclonal antibody (IBT Bioservices, Gaithersburg, MD), mouse anti-flavivirus group antigen monoclonal antibody (EMD Millipore), or mouse monoclonal antibody directed against ZIKV E or NS1 protein (Aalto Bio Reagents, Dublin, Ireland) was incubated with the tissues over-night. An Alexa-flour conjugated secondary antibody (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was then added and incubated for 2 hours. For the infectious assay, horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich) were then incubated for 2 hours, followed by reaction development using a peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA). Images were captured using Zeiss microscope, AxioVision 4.0.1 and processed using Adobe Photoshop.

2.8 Experimental design

A mouse model of ZIKV infection and disease was characterized. Male and female AG129 mice between 8 and 10 weeks were infected subcutaneously (s.c.) with ZIKV (P 6-740). A dose titration of virus was performed to determine a suitable challenge dose of virus for model characterization and antiviral/vaccine studies.

A model characterization study was conducted to identify key time-points of virus replication in various tissues. A cohort of animals was included where survival and weight were monitored to demonstrate consistency with these parameters. Two male and two female mice were necropsied 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 and 13 days after virus challenge. Tissues, including spleen, liver, kidney, brain, and testes/uterus were collected from each animal. Part of each tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde or neutral buffered formalin for at least 24 hours prior to paraffin embedding and sectioning for use in immunohistochemistry analysis described above. Serum and urine were sampled on the same days from a cohort of animals that were infected in parallel for analysis of viral RNA. Total RNA was extracted from tissues and ZIKV RNA was quantified as described above.

For ZIKV infection and antiviral treatment studies, mice were randomly assigned to groups of 10 animals each. A 10−3 dilution (104.0 pfu/mL) of the virus was prepared in MEM. Mice were challenged s.c. with 0.1 mL of the diluted virus (~103.0 pfu/animal). All compound dosages were based on an average mouse weight of 22 g. Compounds were prepared in sterile saline less than 18 hours prior to initial administration in mice and stored at 4°C for the duration of the study. BCX4430 was administered i.m., twice daily (bid) at 300 or 150 mg/kg/d. Ribavirin was given i.p., bid at 75 or 50 mg/kg/d. Treatments began 4 hours prior to virus challenge and continued for 8 days. The identity of the treatment groups was blinded to the technician administering treatments. Mortality was observed twice daily for 28 days, and the weight of each mouse was recorded on day 0 and then every other day from 1-19 days post-virus infection (dpi). Mice were humanely euthanized if they could no longer right themselves or were unresponsive to stimuli.

2.9 Facilities

Experiments were conducted in the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC)-accredited and Public Health Service Animal Welfare Assurance-approved Biosafety level-3 animal suite at the Utah State University Laboratory Animal Research Center (LARC). All LARC personnel continually receive special training on blood-borne pathogen handling by the university's Environmental Health and Safety Office.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Survival data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon log-rank test and all other statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA using a Bonferroni correction for multiplicity where needed (Prism 7, GraphPad Software, Inc).

2.11 Ethics statement

This study, including veterinary care and experimental procedures, was conducted in accordance with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Utah State University under the approved protocol #2550.

3. Results

3.1 Evaluation of antiviral compounds in cell culture

In order to determine the activity of the broad-spectrum antiviral agents BCX4430 and ribavirin, activity was initially evaluated using cytopathic effect (CPE) reduction assays and virus yield reduction (VYR) assays. BCX4430 was found to consistently reduce viral CPE induced by Ugandan, Malaysian and Puerto Rican isolates of ZIKV in RD, Huh-7 and Vero76 cell lines with 50% effective concentration (EC50) values in the low μg/ml range and favorable selective index (SI) values (Table 1). Activity was also similar across the three ZIKV strains tested, representing African, Asian and currently circulating American strains. Activity of BCX4430 was confirmed by VYR tests. The 90% effective concentration (EC90) VYR values were slightly higher but similar to the EC50 (Table 1). The VYR concentration-response curves for BCX4430 were similar in the three different cell lines tested (Figure 1).

Table 1.

In vitro efficacy of BCX4430 and Ribavirin against 3 different ZIKV strains in 3 different cell lines.

| BCX4430 | Ribavirin | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZIKV strain | Cell line | CPE red. assay EC50 (μg/ml)a | VYR assay EC90 (μg/ml)b | SI90c | CPE red. assay EC50 (μg/ml)a | VYR assay EC90 (μg/ml)b | SI90 |

| Puerto Rican PRVABC-59 | Vero76 | 3.8 ± 2.5 | 18.2 ± 2.7 | 5.5 | 23.0 ± 16.8 | 281 ± 108 | 1.1 |

| Huh-7 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 1.2 | 14.9 | 3.8 ± 1.6 | 10.4 ± 0.8 | 30.7 | |

| RD | 4.7 ± 2.2 | 10.0 ± 2.2 | 10.0 | 10.0 ± 6.0 | 46.3 ± 8.6 | 4.3 | |

| Malaysian P 6-740 | Vero76 | 11.5 ± 4.4 | 13.8 ± 3.7 | 7.3 | 143 ± 85.0 | 195 ± 63.6 | 1.6 |

| Huh-7 | 5.5 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 20.5 | 7.2 ± 2.8 | 13.1 ± 0.5 | 24.5 | |

| Ugandan MR-766 | Vero76 | 11.7 ± 4.7 | 8.7 | 11.6 | 85 ± 77.9 | 198 ± 172.5 | 1.6 |

| Huh-7 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 6.4 | 15.7 | 8.9 ± 7.9 | 9.52 ± 2.1 | 33.6 | |

| RD | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 5.4 ± 1.1 | 18.5 | 9.3 ± 5.2 | 13.2 ± 1.7 | 23.1 | |

The 50% effective concentration, or the concentration necessary to reduce viral cytopathic effect by 50%, was determined using a CPE reduction assay conducted three separate times.

90% effective concentration, or the concentration necessary to reduce virus yield from cells harvested on 5 dpi by 1 log10 50% cell culture infectious dose (CCID50%) performed in duplicate (where SD is shown) or in a single test (no SD shown).

90% selective index is obtained by dividing the cytotoxic concentration (not shown), obtained by treating control cells in the absence of virus with serial dilutions of compound and recording dose at which 50% inhibition of cells occurs, by the EC90.

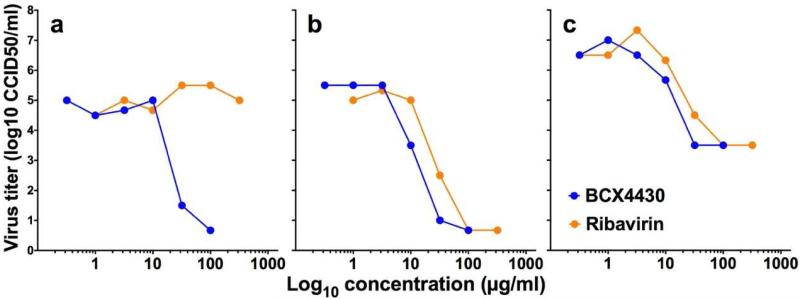

Figure 1.

Reduction of virus yield by BCX4430 or Ribavirin in Vero76 (a), Huh-7 (b) and RD (c) cells as determined using a single test in each cell line.

Ribavirin was also active in cell culture, but with variable results depending on the cell line used (Table 1). Virus yield reduction assays further demonstrated this cell line-dependent variability. Ribavirin was not active against ZIKV infection of Vero76 cells (Figure 1A), despite some activity observed in CPE reduction assays. This was unanticipated as Ribavirin has broad-spectrum activity in this cell line against YFV and West Nile virus (WNV) (Julander et al., 2009; Morrey et al., 2002). Human cell lines, including Huh-7 and RD, confirmed the antiviral activity of Ribavirin (Figures 1B and C, respectively) and provided support for further studies in animal models.

3.2 Establishment of an animal model for ZIKV infection

To further evaluate the effect of BCX4430 and Ribavirin, as well as for use in testing other antivirals and vaccines against ZIKV, we established a model of infection and disease in mice. Wild-type mice typically do not display morbidity or mortality when infected peripherally with ZIKV. For this reason, we selected AG129 mice, which lack type I and type II IFN receptors, due to the susceptible nature of this mouse strain to various viruses (Gowen et al., 2010; Johnson and Roehrig, 1999; Partidos et al., 2011; Thibodeaux et al., 2012).

A Malaysian strain (P 6-740) of ZIKV was titered in mice (data not shown) and a virus challenge dose of 103 pfu/mouse was identified as a suitable dose to cause 100% mortality in AG129 mice after subcutaneous injection (Figure 2a). This challenge dose was used in subsequent experiments. Weight declined rapidly just prior to mortality (Figure 2b) and coincided with disease signs of infected mice, including conjunctivitis, limb weakness or paralysis, excitability, hunching and lying prone (Figure 2c). Infected mice typically displayed one or more symptoms, but the disease signs varied from mouse to mouse.

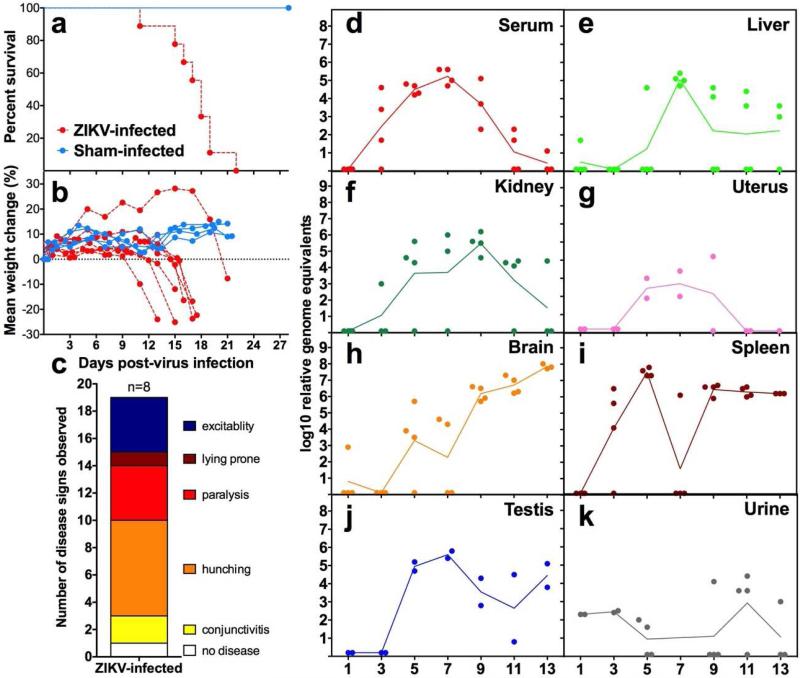

Figure 2.

Survival of ZIKV-infected (n=9) or sham-infected (n=4) AG129 mice (a). Weight change of individual mice measured between 0 and 21 dpi (b) and disease signs (c) of AG129 mice infected with ZIKV. Time-course of ZIKV RNA in serum (d), spleen (e), brain (f), liver (g), kidney (h), urine (i), testis (j) and uterus (k) collected at various times after infection.

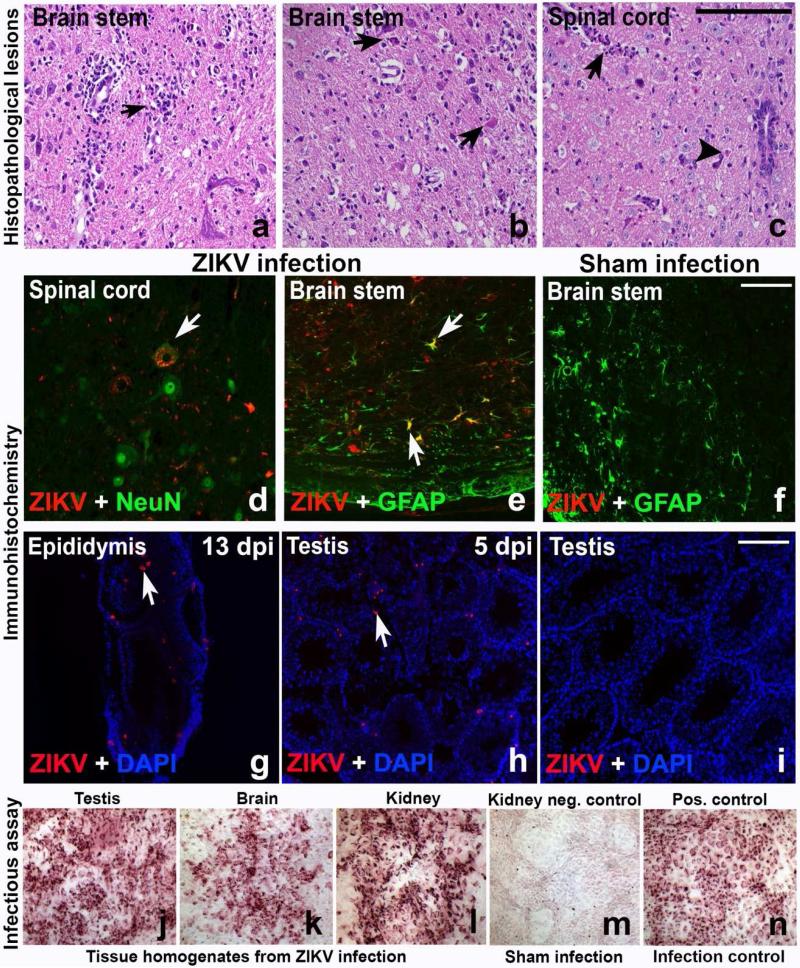

The level of viral RNA accumulation in various tissues was determined by qRT-PCR at various times after infection. Viral RNA levels peaked between 7 and 9 days post-virus inoculation (dpi) and were then cleared from the serum, liver, kidney and uterus (Figure 2d-g). The peak levels of ZIKV RNA present in serum on 5 and 7 dpi (Figure 2d) are useful as an antemortem parameter for use in antiviral studies. Viral RNA in the brain, spleen and testis persisted to 13 dpi at relatively high titers (Figure 2h-j). Viral RNA shedding in the urine was sporadic, although virus was detected as late as 13 dpi (Figure 2k). High viral RNA levels in the brain were consistent with neurological disease signs that were observed just prior to mortality. Neurological signs included locomotor hyperactivity (rapid and uncoordinated running around the cage, either spontaneously or upon disturbance), increased respiratory effort, tremor or seizure, and hunching. Acute multifocal neutrophilic encephalitis with neuronal necrosis was observed in the cerebrum and brain stem (Figures 3a-c, arrows). Similar inflammatory lesions were observed in the cerebellum, but were less severe and mainly focused on the Purkinje cells (data not shown). Multifocal neutrophilic myelitis was also present (Figure 3c, arrowhead). Immunohistochemical staining confirmed ZIKV infection in motor neurons and astrocytes in AG129 adult mice that exhibited hyperactivity (Figures 3d-f). Various areas of the central nervous system had ZIKV-positive cells, including the cerebral cortex, dentate gyrus, hypoglossal nuclei, solitary nucleus, facial nuclei, paragiganto nucleus, entorhinal cortex, brain stem, and pyramid regions, as well as ventral horn motor neurons of the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord, indicating widespread infection in the central nervous system (Figure 3d-e, arrow). ZIKV immunoreactivity was also found in male reproductive tissues, including epididymis and testis, particularly in Leydig cells (Figures 3g-h, arrow). Infectious virus was also detected in various tissues such as testis, brain and kidney (Figures 3j-l) using immunological staining of Vero76 cells after co-cultivation with tissue homogenates. This method, however, was not quantitative so we report the number of samples that were positive using this assay per total samples processed (Table 2). Also reported in Table 2 are the number of samples that contained histological lesions per total observed.

Figure 3.

Histopathologic lesions of ZIKV-infected mice include neutrophilic encephalitis with neuronophagia (a, arrow) and neuronal necrosis (b, arrows) in the brain stem of infected mice. Neutrophilic myelitis (c, arrow) with neuronal necrosis (c, arrowhead) was observed in spinal cord sections. Motor neurons (d, arrow) stained green with NeuN, a neuronal marker, in the ventral horn of spinal cord were infected with ZIKV. Astrocytes in the brainstem (e, arrows), identified by staining with the astrocyte marker GFAP, co-localized with ZIKV. No ZIKV was detected in brain stem sections of a sham control mouse (f) co-stained with anti-ZIKV and anti-GFAP antibodies (scale bar = 50μm). An infectious virus assay was performed using immunohistochemical staining for ZIKV after co-cultivation of tissue homogenates with the indicator Vero 76 cells to verify the presence of ZIKV. Male reproductive tissues, including epididymis (g) and testis (h) were positive for ZIKV, particularly in the Leydig cells (h, arrow). Testis from sham-infected males were included (i). Homogenates from testis (j), brain (k) and kidney (l) were assayed. Kidney homogenates from a sham-infected mouse served as negative controls (m) and ZIKV-infected Vero 76 cells served as a positive control for the assay (n).

Table 2.

Tissue infectious assay and histopathologic diagnoses of adult AG129 mice infected with ZIKV.

| Days post-infection | Tissue infectious assay on indicator Vero 76 cells | Histopathologic lesionsa | ZIKV immunohistochemistryb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney pos./totalc | Liver pos./total | Testis pos./total | Brain pos./total | Brain pos./total | Testis pos./total | Epididymis pos./total | |

| Sham | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

| 3 | 0/4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0/3 | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| 5 | 0/4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0/4 | 2/2 | 0/2 |

| 7 | 3/4 | 2/4 | 0/2 | 2/4 | 0/4 | 2/2 | 2/2 |

| 9 | 0/4 | 1/4 | 2/2 | 3/4 | 4/4d | 0/1 | 0/1 |

| 11 | 2/4 | 0/4 | 2/2 | 2/4 | 4/4d | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| 13 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2/2d | 1/1 | 1/1 |

N/A: Not available.

Histopathologic analysis of kidney, spleen, liver and testis/uterus were also processed and did not have any histopathologic lesions as assessed by a board-certified veterinary pathologist.

Various tissues, including testis and attached epididymis, brain, spleen, liver and kidney were processed. In addition to the results above, spleen also stained positive for ZIKV immunoreactivity after 5 dpi in 2 animals.

Samples that stained positive for ZIKV foci per total number of samples assayed.

Meningoencephalitis was the primary lesion observed in brain sections of ZIKV-infected mice.

3.3 Antiviral efficacy of BCX4430 in vivo

BCX4430 and Ribavirin were evaluated using the AG129 mouse model described above. Each agent was administered for 8 days starting 4 hours prior to virus inoculation. All 16 control mice succumbed, with median survival of 15.5 days. Treatment with 300 mg/kg/d of BCX4430 significantly improved survival (median of >28 days, p<0.001) and protected 7 of 8 mice from mortality (Figure 4a). Mice treated with a lower dose of BCX4430 (150 mg/kg/d) eventually displayed signs of disease and were euthanized; however, there was a significant prolongation of survival (median survival 23 days, p<0.001) (Figure 4a). Ribavirin treatment did not improve outcomes, and at the higher dose of 75 mg/kg/d median survival was 14 days (p<0.01) (Figure 4a).

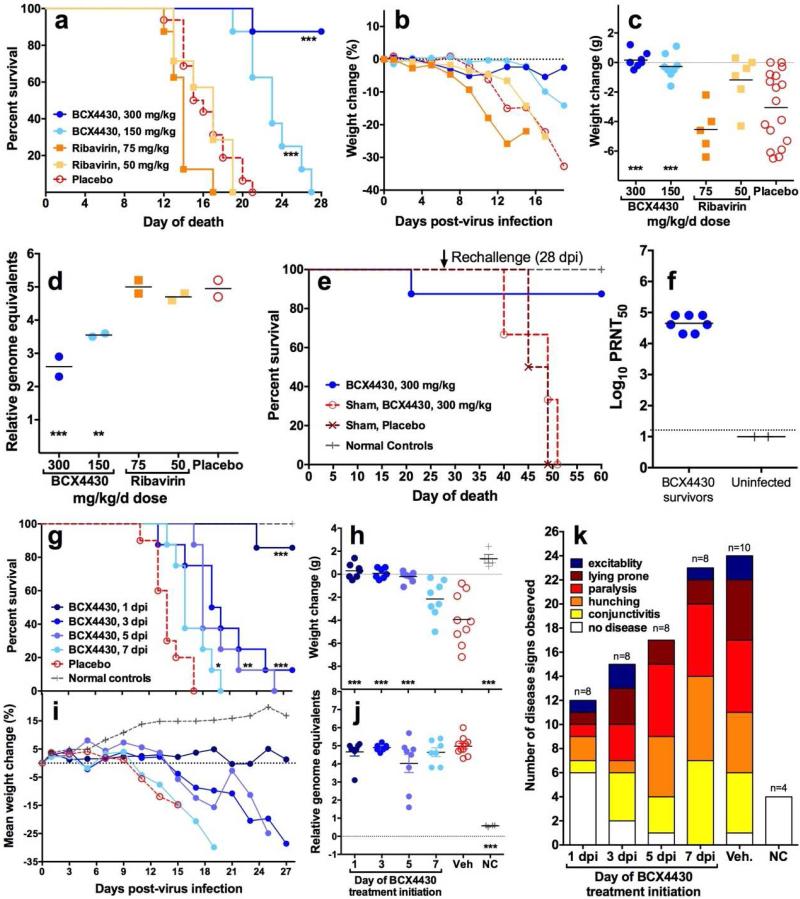

Figure 4.

BCX4430 significantly improved survival (a), time course weight change between 0 and 19 dpi (b), weight change between 7 and 13 dpi (c) and viral RNA in pooled (n=4 per data point) serum on 5 dpi (d) in ZIKV-infected (n=8) or sham-infected (n=3) AG129 mice, while ribavirin treatment did not improve any disease parameter. Surviving mice (n=7) from the initial treatment study with BCX4430 (a) were re-challenged with ZIKV 28 days after the initial viral challenge. Naïve mice that were sham-infected in the first study and treated with either BCX4430 (n=3) or vehicle (n=2) were also challenged. Surviving mice did not succumb to the secondary challenge, while naïve animals had a similar mortality curve to the initial study (e). High neutralizing antibody titers were present just prior to re-challenge in the serum of mice that were treated with BCX4430 (n=7) and survived the initial virus challenge (f). Treatment with BCX4430 was initiated at various times after ZIKV challenge. Survival (g), average weight change between 0 and 28 dpi (h), individual weight change between 7 and 13 dpi (C), mean weight change between 0 and 28 dpi (i), viral RNA from serum on 5 dpi (j) and disease signs (k) observed in BCX4430-treated (n=8) or vehicle treatment controls (n=10) infected mice or uninfected, untreated normal control (n=3) mice were used as disease parameters. Treatment beginning as late as 7 days after virus challenge provided some benefit to ZIKV-infected mice, although survivors were only observed in mice treated beginning 1 or 3 days after ZIKV challenge (***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05, as compared with vehicle control).

Each mouse was weighed serially between 0 and 19 dpi. Weight of animals treated with 300 mg/kg/d of BCX4430 did not decline substantially during that time (Figure 4b) and was similar to sham infected animals treated with the same dose of compound (data not shown). ZIKV-infected vehicle treated animals lost weight rapidly in the days prior to mortality, with a mean change of −3.1 ± 2.4 g from days 7 to 13 (Figure 4c), representing the period between peak weight and just prior to the mean day-to-death in the vehicle group. Mean weight change over the same period in mice treated with BCX4430 300 mg/kg/d or 150 mg/kg/d was +0.2 ± 0.5 and −0.3 ± 0.8 g, respectively (both p<0.001 compared to vehicle). Ribavirin treatment did not protect against weight loss (Figure 4c).

The quantification of viral RNA level in serum isolated from ZIKV-infected mice was performed by real-time qRT-PCR. Comparison of viral RNA level in pooled serum collected on day 5 from ZIKV-infected mice indicated a significant reduction in viremia in groups treated with either dose of BCX4430 (Figure 4d). The reduction in viral load appeared to be dose-dependent. Ribavirin treatment did not improve viral RNA levels in the serum (Figure 4d), which were consistent with survival data.

3.4 Re-challenge of surviving animals

As mentioned above, 7 of 8 mice treated with 300 mg/kg/d of BCX4430 survived ZIKV infection. On day 28 after the initial virus inoculation, these surviving mice were re-challenged with the same challenge dose, route and volume as the initial virus infection. All surviving mice from the initial infection also survived the secondary challenge (Figure 6A). Naïve mice that were used as sham-infection controls during the initial phase of the study were also infected on day 28 and succumbed to ZIKV challenge by 23 days after virus challenge as expected (day 51 on Figure 4e). High neutralizing antibody titers (4-5 log10 PRNT50) were present in serum samples taken just prior to re-challenge from BCX4430-treated mice that survived initial ZIKV challenge (Figure 4f). As expected, mice that were initially uninfected did not have detectable levels of ZIKV-neutralizing antibody prior to infection in the re-challenge study (Figure 4f).

3.5 Therapeutic treatment with BCX4430

A second study was conducted to determine the effect of treatment initiated at various times after ZIKV challenge. A dose of 300 mg/kg/d was given bid for 7 days beginning 1, 3, 5 or 7 dpi. Six of 7 mice were protected from mortality when treatment was initiated 1 day after ZIKV challenge (Figure 4g). Median survival was significantly prolonged in all BCX4430-treated groups, with median survival of >28, 19.5, 18 and 17 days for treatment beginning on days 1, 3, 5 or 7 dpi, respectively (overall p<0.0001 compared with vehicle), although only a single mouse survived in the day 3 treatment initiation group (Figure 4g).

Weights declined as animals became moribund. Significant protection from weight loss between 7 and 13 dpi was observed in mice treated with BCX4430 beginning 1, 3 or 5 dpi, as compared with vehicle control (p<0.001) (Figure 4h). The average percent weight change of animals treated with BCX4430 beginning on 1 dpi remained near baseline, while treatment initiation at progressively later times was associated with earlier declines in weight (Figure 4i). The weight change curve of animals treated beginning 7 dpi was similar to that of the vehicle treatment group. Normal control animals gained weight over the course of the study.

Despite improvement in survival and weight change, viral RNA levels in serum on 5 dpi were not significantly decreased in groups treated with BCX4430 beginning 1 or 3 dpi (Figure 4j). A progressive decrease in the number of disease signs was observed in the groups with treatment initiated at earlier timepoints, an effect that roughly corresponded to delayed mortality and protection from weight loss (Figure 4k).

4. Discussion

Several models of ZIKV infection in mice have been reported over the last year, mainly in immune deficient mouse strains (Aliota et al., 2016; Lazear et al., 2016; Rossi et al., 2016; Zmurko et al., 2016). The AG129 mouse strain was shown to be useful in antiviral studies (Zmurko et al., 2016). These mice are sensitive to ZIKV-induced disease, but do not succumb until 2-3 weeks after virus challenge, which provides an ample window to test different aspects of antiviral therapy, including post-exposure therapy and identification of compounds that could be used to treat severe outcomes such as encephalitis.

Herein, we characterized the course of ZIKV-induced disease in the AG129 mouse model after exposure with an Asian ZIKV strain. Virus replication in various key organs, including the brain, spinal cord and urogenital tract, provides a sensitive in vivo model that can be used to identify effective treatments and vaccines. ZIKV infection of AG129 mice, however, only models certain aspects of disease since the uniformly lethal phenotype is much more severe than natural infection. Due to the extremely aggressive and fatal course of infection, antiviral therapies must possess potent activity to show benefit in this model. Some differences, such as delayed viremia, were observed as compared with other models described in the literature (Aliota et al., 2016), but these could be due to differences in detection methods, virus strain used or source of mice.

Severe neurologic manifestations, including excitability with associated tremors, myoclonic twitching, increased respiratory effort and locomotor hyperactivity, were observed in ZIKV-infected adult AG129 mice. During uncoordinated excitable running events, ataxic circling of the cage was usually followed by tremors, often displayed while lying prone. Mortality generally followed 24-48 hours after first observing these neurologic signs. Hyperactivity is also observed during infection with borna disease virus, a neurotropic non-cytolytic RNA virus (Hornig et al., 1999). The infection pattern of ZIKV in the central nervous system was similar to that of the related flavivirus WNV that also infects motor neurons in the ventral horn of spinal cord (Siddharthan et al., 2009) and the brain stem (Morrey et al., 2010), although ZIKV infected cells generally co-localized with astroglial cells while WNV is more neuron-specific. We have also observed a similar infection of astroglial cells after Venezulan equine encephalitis virus infection in a C3H/HeN mouse model (Julander et al., 2008).

BCX4430 is a broad-spectrum antiviral that is potently active against a wide variety of RNA viruses including YFV, EBOV and MARV in animal models (Julander et al., 2014; Warren et al., 2014). The efficacy of BCX4430 in a lethal ZIKV infection described herein represents the first time that protection from ZIKV-associated mortality has been demonstrated in a mouse model. Treatment with another nucleoside analog significantly prolonged median survival time, but did not result in animals surviving infection (Zmurko et al., 2016). The protective effect of BCX4430 was also observed when treatment was initiated 24 hours after virus challenge and significant (P<0.001) delays in mortality occurred when treatment was delayed as much as 5 dpi, coinciding with peak virus titer in the serum. Ribavirin, another broad-spectrum antiviral that is efficacious in the hamster model of YFV, did not improve outcome from ZIKV infection in AG129 mice. These results further underscore the broad-spectrum efficacy of BCX4430 and provide justification for continued development.

While these studies are important in demonstrating antiviral activity of the compound against ZIKV, the utility of BCX4430 in preventing more serious consequences of ZIKV infection, such as congenital infection and sexual transmission, should be evaluated. There is a precedent in the HIV field for the use of antiviral treatment during pregnancy. Vertical transmission with HIV has been shown to be RNA copy number-dependent, with higher rates occurring with increasing viral loads present in the mother (O'Shea et al., 1998). Treatment of pregnant women has been demonstrated to drastically reduce the incidence of vertical transmission in women undergoing treatment with a combination of antiretroviral compounds (Cooper et al., 2002). Treatment, however, may result in negative outcomes to fetal development and maternal health (Huntington et al., 2015; Papp et al., 2015). Despite the obvious hurdles associated with the treatment of ZIKV infection in pregnant women, we anticipate there could be an important role played by antiviral therapies and are planning additional murine model studies to delineate the activity of BCX4430 for prevention of congenital infection.

Highlights.

Protective efficacy of BCX4430 in various cell lines and in a lethal mouse model, including therapeutic treatment

Treatment with BCX4430 doesn’t preclude antibody response

Time-course detection of viral RNA and infectious virus in various tissues

Pathology in the brain and spinal cord of infected mice

Detection of persistent virus in the testis

Acknoweldgements

We thank Heidi Julander for maintaining the AG129 colonies and Thomas Ditton, Neil Motter, Jared Bennett, Jason Fairborne, Rachelle Stanton, Devin Pfister, John McClatchy, Jean Maxwell, Mitch Stevensen and Sabrina Anderson for their technical assistance in performing animal studies and data analysis. We also thank Jana Kent and Joseph Featherstone of Co-Diagnostics Inc. for generous provision of reagents and assistance with their quantitative qRT-PCR assay for detecting ZIKV RNA. This work was supported by the Virology Branch, NIAID, NIH [HHSN272201000039I, Task Order A90 and HHSN272201100019I/HHSN27200016, Task Order B23].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aliota MT, Caine EA, Walker EC, Larkin KE, Camacho E, Osorio JE. Characterization of Lethal Zika Virus Infection in AG129 Mice. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004682. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo LM, Ferreira ML, Nascimento OJ. Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with the Zika virus outbreak in Brazil. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2016;74:253–255. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20160035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocklehurst P, Volmink J. Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD003510. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ER, Charurat M, Mofenson L, Hanson IC, Pitt J, Diaz C, Hayani K, Handelsman E, Smeriglio V, Hoff R, Blattner W, Women, Infants' Transmission Study, G. Combination antiretroviral strategies for the treatment of pregnant HIV-1-infected women and prevention of perinatal HIV-1 transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:484–494. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro MT, Pena LJ, Brito CA, Gil LH, Marques ET. Positive IgM for Zika virus in the cerebrospinal fluid of 30 neonates with microcephaly in Brazil. Lancet. 2016;387:1811–1812. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30253-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa F, Sarno M, Khouri R, de Paulo Freitas B, Siqueira I, Ribeiro GS, Ribeiro HC, Campos GS, Alcantara LC, Reis MG, Weaver SC, Vasilakis N, Ko AI, Almeida AR. Emergence of Congenital Zika Syndrome: Viewpoint From the Front Lines. Ann Intern Med. 2016 doi: 10.7326/M16-0332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Fatima Vasco Aragao M, van der Linden V, Brainer-Lima AM, Coeli RR, Rocha MA, Sobral da Silva P, Durce Costa Gomes de Carvalho M, van der Linden A, Cesario de Holanda A, Valenca MM. Clinical features and neuroimaging (CT and MRI) findings in presumed Zika virus related congenital infection and microcephaly: retrospective case series study. BMJ. 2016;353:i1901. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirlikov E, Major CG, Mayshack M, Medina N, Matos D, Ryff KR, Torres-Aponte J, Alkis R, Munoz-Jordan J, Colon-Sanchez C, Salinas JL, Pastula DM, Garcia M, Segarra MO, Malave G, Thomas DL, Rodriguez-Vega GM, Luciano CA, Sejvar J, Sharp TM, Rivera-Garcia B. Guillain-Barre Syndrome During Ongoing Zika Virus Transmission -Puerto Rico, January 1-July 31, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:910–914. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6534e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowall SD, Graham VA, Rayner E, Atkinson B, Hall G, Watson RJ, Bosworth A, Bonney LC, Kitchen S, Hewson R. A Susceptible Mouse Model for Zika Virus Infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driggers RW, Ho CY, Korhonen EM, Kuivanen S, Jaaskelainen AJ, Smura T, Rosenberg A, Hill DA, DeBiasi RL, Vezina G, Timofeev J, Rodriguez FJ, Levanov L, Razak J, Iyengar P, Hennenfent A, Kennedy R, Lanciotti R, du Plessis A, Vapalahti O. Zika Virus Infection with Prolonged Maternal Viremia and Fetal Brain Abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2142–2151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatherer D, Kohl A. Zika virus: a previously slow pandemic spreads rapidly through the Americas. J Gen Virol. 2015 doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowen BB, Wong MH, Larson D, Ye W, Jung KH, Sefing EJ, Skirpstunas R, Smee DF, Morrey JD, Schneller SW. Development of a new tacaribe arenavirus infection model and its use to explore antiviral activity of a novel aristeromycin analog. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornig M, Weissenbock H, Horscroft N, Lipkin WI. An infection-based model of neurodevelopmental damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12102–12107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington S, Thorne C, Newell ML, Anderson J, Taylor GP, Pillay D, Hill T, Tookey PA, Sabin C, Study, U.K.C.H.C., Uk, Ireland National Study of, H.I.V.i.P., Childhood Pregnancy is associated with elevation of liver enzymes in HIV-positive women on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2015;29:801–809. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AJ, Roehrig JT. New mouse model for dengue virus vaccine testing. J Virol. 1999;73:783–786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.783-786.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julander JG, Bantia S, Taubenheim BR, Minning DM, Kotian P, Morrey JD, Smee DF, Sheridan WP, Babu YS. BCX4430, a novel nucleoside analog, effectively treats yellow fever in a Hamster model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:6607–6614. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03368-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julander JG, Shafer K, Smee DF, Morrey JD, Furuta Y. Activity of T-705 in a hamster model of yellow fever virus infection in comparison with that of a chemically related compound. T-1106. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:202–209. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01074-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julander JG, Skirpstunas R, Siddharthan V, Shafer K, Hoopes JD, Smee DF, Morrey JD. C3H/HeN mouse model for the evaluation of antiviral agents for the treatment of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2008;78:230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazear HM, Diamond MS. Zika Virus: New Clinical Syndromes and its Emergence in the Western Hemisphere. J Virol. 2016 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00252-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazear HM, Govero J, Smith AM, Platt DJ, Fernandez E, Miner JJ, Diamond MS. A Mouse Model of Zika Virus Pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:720–730. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Xu D, Ye Q, Hong S, Jiang Y, Liu X, Zhang N, Shi L, Qin CF, Xu Z. Zika Virus Disrupts Neural Progenitor Development and Leads to Microcephaly in Mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JJ, Cao B, Govero J, Smith AM, Fernandez E, Cabrera OH, Garber C, Noll M, Klein RS, Noguchi KK, Mysorekar IU, Diamond MS. Zika Virus Infection during Pregnancy in Mice Causes Placental Damage and Fetal Demise. Cell. 2016;165:1081–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, Popovic M, Poljsak-Prijatelj M, Mraz J, Kolenc M, Resman Rus K, Vesnaver Vipotnik T, Fabjan Vodusek V, Vizjak A, Pizem J, Petrovec M, Avsic Zupanc T. Zika Virus Associated with Microcephaly. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:951–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrey JD, Siddharthan V, Wang H, Hall JO, Motter NE, Skinner RD, Skirpstunas RT. Neurological suppression of diaphragm electromyographs in hamsters infected with West Nile virus. J Neurovirol. 2010;16:318–329. doi: 10.3109/13550284.2010.501847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrey JD, Smee DF, Sidwell RW, Tseng C. Identification of active antiviral compounds against a New York isolate of West Nile virus. Antiviral Res. 2002;55:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noronha L, Zanluca C, Azevedo ML, Luz KG, Santos CN. Zika virus damages the human placental barrier and presents marked fetal neurotropism. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2016;111:287–293. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760160085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea S, Newell ML, Dunn DT, Garcia-Rodriguez MC, Bates I, Mullen J, Rostron T, Corbett K, Aiyer S, Butler K, Smith R, Banatvala JE. Maternal viral load, CD4 cell count and vertical transmission of HIV-1. J Med Virol. 1998;54:113–117. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199802)54:2<113::aid-jmv8>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp E, Mohammadi H, Loutfy MR, Yudin MH, Murphy KE, Walmsley SL, Shah R, MacGillivray J, Silverman M, Serghides L. HIV protease inhibitor use during pregnancy is associated with decreased progesterone levels, suggesting a potential mechanism contributing to fetal growth restriction. J Infect Dis. 2015;211:10–18. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partidos CD, Weger J, Brewoo J, Seymour R, Borland EM, Ledermann JP, Powers AM, Weaver SC, Stinchcomb DT, Osorio JE. Probing the attenuation and protective efficacy of a candidate chikungunya virus vaccine in mice with compromised interferon (IFN) signaling. Vaccine. 2011;29:3067–3073. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos da Silva S, Gao SJ. Zika virus: An update on epidemiology, pathology, molecular biology, and animal model. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1291–1296. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SA, Jamieson DJ, Honein MA, Petersen LR. Zika Virus and Birth Defects--Reviewing the Evidence for Causality. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1981–1987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1604338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi SL, Tesh RB, Azar SR, Muruato AE, Hanley KA, Auguste AJ, Langsjoen RM, Paessler S, Vasilakis N, Weaver SC. Characterization of a Novel Murine Model to Study Zika Virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016 doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddharthan V, Wang H, Motter NE, Hall JO, Skinner RD, Skirpstunas RT, Morrey JD. Persistent West Nile virus associated with a neurological sequela in hamsters identified by motor unit number estimation. J Virol. 2009;83:4251–4261. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00017-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibodeaux BA, Garbino NC, Liss NM, Piper J, Blair CD, Roehrig JT. A small animal peripheral challenge model of yellow fever using interferon-receptor deficient mice and the 17D-204 vaccine strain. Vaccine. 2012;30:3180–3187. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren TK, Wells J, Panchal RG, Stuthman KS, Garza NL, Van Tongeren SA, Dong L, Retterer CJ, Eaton BP, Pegoraro G, Honnold S, Bantia S, Kotian P, Chen X, Taubenheim BR, Welch LS, Minning DM, Babu YS, Sheridan WP, Bavari S. Protection against filovirus diseases by a novel broad-spectrum nucleoside analogue BCX4430. Nature. 2014;508:402–405. doi: 10.1038/nature13027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu KY, Zuo GL, Li XF, Ye Q, Deng YQ, Huang XY, Cao WC, Qin CF, Luo ZG. Vertical transmission of Zika virus targeting the radial glial cells affects cortex development of offspring mice. Cell Res. 2016;26:645–654. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yockey LJ, Varela L, Rakib T, Khoury-Hanold W, Fink SL, Stutz B, Szigeti-Buck K, Van den Pol A, Lindenbach BD, Horvath TL, Iwasaki A. Vaginal Exposure to Zika Virus during Pregnancy Leads to Fetal Brain Infection. Cell. 2016;166:1247–1256. e1244. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zmurko J, Marques RE, Schols D, Verbeken E, Kaptein SJ, Neyts J. The Viral Polymerase Inhibitor 7-Deaza-2′-C-Methyladenosine Is a Potent Inhibitor of In Vitro Zika Virus Replication and Delays Disease Progression in a Robust Mouse Infection Model. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]