Abstract

Background

Non-adherence to immunosuppressant medication is prevalent in kidney transplant recipients and has been associated with increased risk for graft failure and economic burden. The aim of this pilot study was to test whether a culturally sensitive cognitive-behavioral adherence promotion program could significantly improve medication adherence to tacrolimus prescription as measured by telephone pill counts among kidney transplant recipients.

Methods

Thirty-three adult transplant recipients were less than 98% adherent to tacrolimus prescription based on three telephone pill counts, were randomized to either the two-session cognitive-behavioral adherence promotion program or standard care. The curriculum was developed from an iterative process with transplant recipients into a 2-session group program that provided psychoeducation, addressed barriers to adherence, fostered motivation to improve adherence behavior, and discussed cultural messages on adherence behavior.

Results

The intervention group displayed significantly higher levels of adherence when compared to the control group (t=2.2, p=.04) and. similarly, when the amount of change was compared between the groups, the intervention group showed more change than the control condition (F (22,1) = 12.005, p=.003). Tacrolimus trough concentration levels were used as secondary measure of adherence and while, there were no significant between-group differences for mean trough concentration levels, the variability in the trough levels did significantly decrease over time indicating more consistent pill taking behavior in the intervention group.

Conclusions

There is preliminary support for the pilot program as a successful intervention in helping patients their immunosuppressant medication.

Keywords: Kidney transplant, immunosuppressive therapy, randomized clinical trial

Introduction

Poor adherence to medication regimens accounts for substantial worsening of disease, death, and increased health care costs in the United States [1–3]. Lower adherence to immunosuppressant drugs has been associated with increased cost [4], decreased graft survival [5–6] and higher rates of mortality [7–8]. Kidney graft recipients who are non-adherent to their immunosuppressive medications are at an increased risk of infection, acute rejection episodes, chronic rejection, and ultimately graft failure [9–10]. Despite increased risk for negative consequences, non-adherence is more common in kidney transplant recipients [11], with reported rates of non-adherence ranging from 5% to 68% [12–13].

Several studies have identified patient characteristics associated with non-adherence to immunosuppressant medications in transplant recipients, with mixed evidence indicating racial/ethnic minority groups are less adherent [14–26]. The reasons for these racial disparities in renal transplant recipients are unclear, but are probably multifaceted [27].

Patient's perception of the perceived risks and benefits of following medical advice has been posited as a key factor in predicting behavior by the Health Belief Model (HBM). The HBM has been used in a variety of contexts, including adherence to medical prescription [28]. Perceived barriers and benefits are consistently the strongest predictors of the broad array of health behaviors in a variety of medical populations [29] and specifically adherence behaviors [30]. Resnicow's model of cultural sensitivity similarly emphasizes the importance of understanding how members of a target population perceive their illnesses in order to modify health behaviors and has been used to guide the development of various health promoting interventions [31, 32]. Therefore, the identification of salient barriers to medication adherence in a particular population, is vital to the development of targeted adherence interventions.

Several barriers to taking immunosuppressant medication in renal transplant patients have been previously identified [33]. In our previous work [34], we found that there were different pathways to non-adherence, with some people acknowledging that they deliberately chose to not take their medication (e.g. because of side effects) and others identifying barriers that were beyond their control (e.g. inadequate finances). Both types of barriers were associated with increased non-adherence. We have also demonstrated an association between depression and survival and posited that this relationship may be mediated by various psychological and physiological factors, with treatment nonadherence representing one potential pathway. Depressive symptoms of low motivation, impaired concentration, and apathy may well significantly interfere with patients' adherence to treatment for ESRD [35].

In reviews of medication adherence promotion interventions in mixed medical populations, the most successful methods include combinations of behavioral interventions and reinforcements in addition to providing educational information about the patient's condition and the treatment [36–38]. Few studies have systematically tested behavioral interventions in renal transplant patients. In a study of adult renal transplant recipients, medication non-adherence was higher for participants in the control group compared to those who received an education/counseling intervention [39]. In a small pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT), investigators tested the efficacy of an educational and behavioral group intervention in the reduction of non-adherence as measured by MEMs caps. While the intervention group had greater improvement in adherence at the end of the intervention as compared to a standard care group, these effects did not reach statistical significance and both groups returned to pre-intervention non-adherence levels at the end of the 6-month follow-up [40]. In a more recent study, 15 adult renal transplant patients were randomly assigned to either a continuous self-improvement intervention or to an attention control group. At study conclusion participants receiving the self-improvement intervention had significantly higher electronically monitored medication adherence scores as compared to the control group [41].

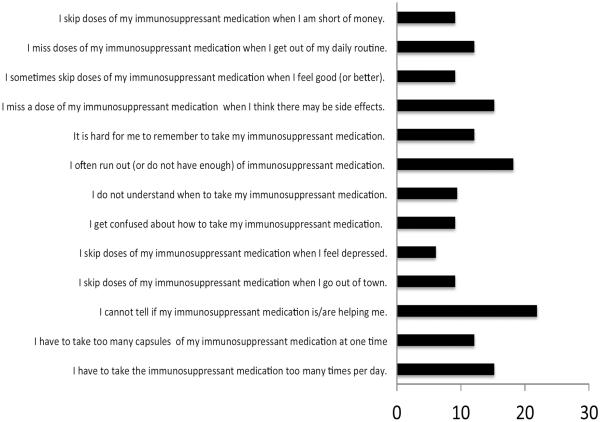

As suggested by Russell (2006) [42] there is a need for cultural adaptation of transplant intervention in minority populations, so in preliminary work for this study, we gathered survey data and held focus groups to better understand Black kidney transplant recipients' and health care providers' perceptions of the most salient motivations and barriers to immunosuppressant adherence. Fifty patients over the age of 18 who underwent kidney transplantation not less than 6 months prior were asked to complete a survey (Immunosuppressant Therapy Barriers Scale: ITBS) [43] (see Figure 1) and some (n=10) were available to further answer questions about the key benefits and barriers to adherence. Similarly a group of health care professionals (n=5) (transplant nephrologists, transplant coordinators) also provided input around their perception of key barriers to immunosuppressant adherence and parameters for the intervention programs. The development of the current adherence promotion study was informed by the feedback obtained. As an example, based upon patient feedback, the decision was made not to include conditions that require any form of deception, as there were high levels of mistrust in clinical research. Consequently, the study assessments were blinded, but participants would not be subjected to placebo treatment.

Figure 1.

Percent of sample endorsing as a substantive barrier

The primary aim of this study was to pilot a culturally sensitive adherence promotion program for kidney transplant recipients who were less than ideally adherent to immunosuppressant prescription. We sought to examine whether exposure to an adherence promotion program would result in improved medication adherence (specifically, taking and persistence [44]) as compared to standard care provided by the nephrology treatment team.

Methods

This randomized controlled trial was designed to pilot the culturally sensitive adherence promotion program that was developed using information gathered from our preliminary surveys and focus groups with transplant patients and providers. Inclusion criteria for the study included kidney transplant patients with a current prescription of daily tacrolimus, over the age of 25, and less than 98% adherence to medication prescription, as determined by three baseline pill counts (described below). Tacrolimus (FK506, Prograf®) is an immunosuppressant drug that has emerged as the gold standard for the prevention of graft rejection following kidney transplantation. Exclusion criteria were lack of telephone to complete pill counts and lack of English proficiency to participate in adherence promotion sessions. English proficiency was assessed based on participant's ability to answer screening questions and questionnaires administered in English.

Measures

Adherence Measurement

Primary - Phone Pill Counts

While there are a variety of direct [45] and indirect techniques [1] available to measure medication adherence, there are relative advantages and disadvantages to the various assessment types, balancing accuracy, cost, and burden [46]. Ultimately, it was decided not to rely on the commonly used electronic monitoring caps, as there is evidence that they can alter medication taking behaviors [47]. An alternative strategy to measuring adherence is in-person pill counts. However, the burden of this type of measurement is high [48]. Telephone-pill counts have been examined as an alternative to in-person pill counts in a variety of medical populations [45, 49–52]. Kalichman and colleagues [50–51] found that unannounced telephone pill counts paralleled the ability of office-based and home-based pill counts to measure adherence to antiretroviral medication (with an interclass correlation coefficient between phone and home pill counts of .997, P<.001) while also mitigating the logistical challenges that encumber office- and home-based visits. Thus, we selected this method of adherence measurement as the pill count methodology is not specific to the type of pill or disease being studied.

Participants were contacted for three pre- and post-intervention telephone pill counts. At each call, the research assistant (RA) instructed the participant to count all of their Tacrolimus pills over the phone using a pill tray that was provided by the study. The count was repeated a second time to ensure accuracy. If there was discrepancy, pills were recounted until 2 consecutive counts agreed. The RA recorded the current pill count, prior pill count and number of prescriptions filled. This allowed the RA to inquire about any possible change in medication regimen. Using this information, an adherence percentage was calculated for each pill count. Due to the possible emergent consequences of extreme non-adherence, if the participant reported skipping 3 consecutive days, the treating physician would be contacted for follow-up and study participation ended.

Adherence percentage was determined by calculating the difference in two pill phone counts over the expected numbers of pills to be taken given the length of time between the counts (pill count 2 – pill count 1/expected number of pills). Two adherence percentages were averaged to form a baseline measure of adherence. Similarly, three additional pill counts at follow-up were conducted, yielding two adherence percentage scores, that were then averaged.

Secondary - Tacrolimus Trough Concentration Levels

Tacrolimus whole -blood samples, used for the determination of 12h tacrolimus trough concentrations, were collected as part of the patient's usual clinical care. Trough concentrations have been found to correlate well with area under the concentration–time curve measurements in kidney transplant recipients (r=0.91–0.99) [53]. Thus trough concentrations are a good index of overall drug exposure, and are currently used for routine monitoring as part of patient care post-transplantation. Blood for trough concentration measurements was collected before the morning dose. Tacrolimus concentrations were determined by high performance liquid chromatographic method.

Psychological Functioning Measurement

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II)

The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report instrument with high scores (range = 0 to 63) reflecting the presence and severity of depressed mood [54]. Depressed mood was assessed to measure psychological functioning of our sample.

Study Procedures

This study was approved by the SUNY Downstate IRB and informed consent was documented for all participants. Patients were approached in the waiting room of the transplant clinic and asked to complete a 10-minute screen for potential eligibility. This assessment included measures of self-reported adherence, depression and sociodemographics. Patients were approached consecutively until desired recruitment was reached.

Within one week after completing the in-office baseline measures eligible participants were contacted for an initial telephone pill count. Participants were then contacted twice within four weeks to complete a second and third unannounced telephone pill count. The three pill counts were used to calculate a baseline medication adherence percentage, which was used to determine eligibility for the intervention phase of the study. If the participant demonstrated an average of less than 98% adherence across calls, they were considered eligible for the intervention and were randomly assigned, using a 1:1 random number allocation strategy, to either the treatment condition or the standard care condition. Randomization was done through random number sequences generated (no blocks) before the study began. The person doing the randomization kept the information concealed from the independent assessor and participants were instructed not to share their group assignment with the assessor.

This stringent adherence cutoff was selected based on the input from focus groups. It has been demonstrated that even minor non-adherence to immunosuppressant medication can affect maintenance of a transplant organ [55]. Specifically, there is evidence from previous research that shows that minimal deviations from the prescribed regimen were associated with increased risk of graft rejection in renal transplant recipients [55–58]. Beginning 6 weeks after randomization, all participants were contacted biweekly to complete three additional follow-up telephone pill counts. During the final telephone call participants were asked to complete a brief post-treatment assessment. Participants received $5 for completing the baseline assessment, post-treatment assessment and for each completed telephone pill count. Participants were not compensated for their time at the adherence promotion sessions but lunch and transportation costs were provided.

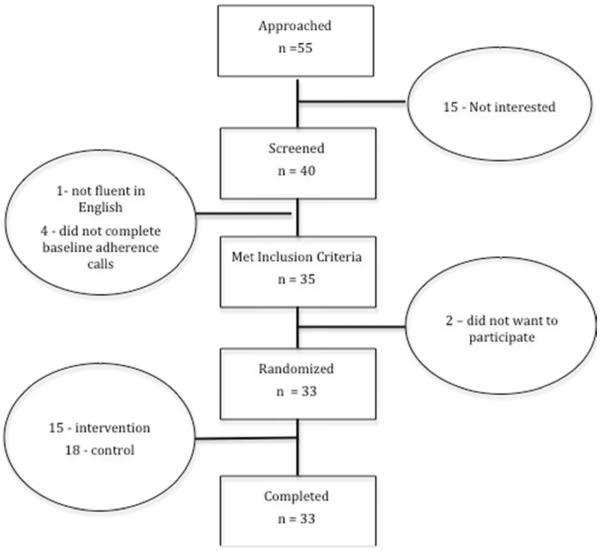

In total, 55 kidney transplant recipients were approached for participation while waiting for their medical appointments. Forty individuals agreed to undergo the phone pill count to determine eligibility. No information was collected on those who did not participate. Of these, baseline adherence level was collected on 35 (i.e., participated in phone counts). All of them were eligible to participate (adherence <98%), and 33 agreed to be randomized (see Figure 2). All randomized participants completed the study. No participants in either condition reported 3 consecutive days of skipped doses, and consequently, no one's participation was terminated early. Data was collected from 1/11 – 12/11. There were no changes to study procedure during the course of the study.

Figure 2.

Participant Flow

Treatment Arms

Intervention Condition

The treatment condition consisted of a two-session group intervention that was initiated within two weeks of randomization. Between four and six participants were invited to participate in a group. The sessions were each 2 hours long and were held in an outpatient office suite. Three separate groups of participants completed the two-session intervention and sessions were held between one and two weeks apart.

Intervention

Our adherence promotion intervention incorporated techniques derived from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and Motivational Interviewing (MI) techniques. CBT is a short-term, focused psychotherapy for a wide range of psychological and behavioral issues. The focus of the intervention is on how one thinks, behaves, and communicates in present time, as opposed to a focus on one's early childhood experiences. The intervention is action-oriented, practical, rational, and helps the patient gain independence and effectiveness in dealing with real-life issues [59–61]. MI is a client-centered, semi-directive method of engaging intrinsic motivation to change behavior by developing discrepancy as well as exploring and resolving ambivalence [62–64]. MI is non-confrontational and attempts to increase the patient's awareness of the potential problems caused, consequences experienced, and risks faced as a result of the behavior in question and seeks to help patients consider what might be gained through change.

Standard CBT interventions for non-adherence were modified and adapted for 1) the particular challenges associated with being a transplant patient, and 2) the cultural needs and African American patients receiving transplant services.

Information gathered from preliminary focus groups was integrated and resulted in a small-group intervention that included the components described in Table 1. The intervention was administered by doctoral level psychologists (DC and NVH).

Table 1.

Small Group Intervention Components

| Component | Description | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Psychoeducation | Addresses the difference between compliance and adherence, the role of side effects in choosing not to take medication, physician mistrust, over-prescription of medication, and safety of medication – targets HBM's constructs of perceived susceptibility and perceived severity | Week 1 |

| Barriers | Identification of specific barriers to adherence with particular emphasis on maintaining adherence despite limited resources - targets HBM's constructs of perceived barriers | Week 1 |

| Motivational Interviewing | Exploring readiness for change and motivation to improve adherence behavior-targets HBM's constructs of perceived barriers and benefits | Week 1 |

| Behavior Modification | Utilizing behavioral modification to develop strategies to address personal barriers- directly targets HBM's construct of health behavior activity | Week 2 |

| Affect Awareness | Increasing awareness of impact of mood on adherence behavior -targets HBM's constructs of cues to action | Week 2 |

| Cultural Tailoring | Impact of group and cultural messages on adherence attitudes and behaviors - targets HBM's constructs of perceived threat | Week 2 |

Control Condition

Participants in the control condition completed the same number of unannounced telephone pill counts at the same intervals as participants in the intervention condition. They did not receive any additional information or intervention regarding their adherence behavior outside of standard care, which involved monthly appointments with the nephrology transplant treatment team to assess kidney functioning and address any issues presented by the provider or the patient. This treatment as usual plus monitoring condition was selected as the appropriate control for several reasons. Due the pilot nature of the trial, patient feedback about the undesirability of sham placebo conditions, and the limited sample size, having two active treatments would have surpassed our power estimates [65]. Furthermore, there has been scant evidence that behavioral intervention is effective in this population and any attention-matched control, would in essence be another active treatment arm. Finally, while there is increased threat to internal validity by using a treatment as usual condition, there is greater ecological validity in that this represents standard clinical practice.

Statistical Analyses

We used the Statistical Software Package of Social Science (SPSS, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) version 21.3 to conduct analyses. Demographic and clinical variables were expressed, as appropriate, in frequencies, mean and standard deviations. We used Intention-to-Treat principles for analysis. To test whether adherence levels differed between the study groups at baseline and outcome, we created an adherence score by averaging the 3 baseline pill count data and then the 3 follow-up pill count data. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

We used chi-square analyses to assess differences between groups in all categorical variables and t-tests were used to compare differences between groups on continuous variables. Outcome data was similarly compared using t-tests to evaluate mean differences between groups. Linear regression modeling was used to determine within group changes for both the intervention and control conditions.

Results

Baseline differences between those assigned to the treatment group and those assigned to the control group were evaluated (Table 2). There were no significant between-group baseline differences in demographic, medical, or psychological variables (p > 0.05, all cases). The sample's pre-treatment mean adherence score was 93% adherent (range .83–.98).

Table 2.

Sample Descriptive Characteristics (mean (SD) range)

| Total Sample | Control Condition (n=18) | Intervention Condition (n-15) | Inferential statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52.1 (11.9) 35–74 | 49.1 (12.3) 35–74 | 55.6 (10.7) 38–72 | t=1.6, p>.05 |

| Gender | 60% female | 55% female | 67% female | Chi2 = .29, p>.05 |

| Race | 88% Black | 89% Black | 88% Black | Chi2 = .34, p>.05 |

| Months since transplant | 37.6 (13.4) 8–71 | 31.4 (12.8) 18–71 | 39 .4 (14.8) 8–66 | t=96, p>.05 |

| Diabetic | 48% | 42% | 52% | Chi2 = .47, p>.05 |

| Depression (BDI) | 11.1(9.3) 6–38 | 10.5(10.2) 8–38 | 11.8(8.4) 6–32 | t=.39, p>.05 |

The group scores on the self-report of depression (BDI) reflect a slight elevation of depressive affect, and are consistent with our earlier work with kidney transplant recipients [33]. No adverse events were detected in either group over the course of the study.

Adherence – Phone Pill Counts

Based upon phone pill counts, there was a significant change in the intervention group mean adherence, which improved from 92% to 98%, while there was no observable improvement in the control group (94% to 94%) (Table 3). At study completion, the intervention group displayed significantly higher levels of adherence when compared to the control group (t=2.2, p=.04) and. similarly, when the amount of change was compared between the groups, the intervention group showed more change than the control condition (F (22,1) = 12.005, p=.003).

Table 3.

Group Changes in Adherence as measured by phone pill count and trough Tacrolimus levels

| Group | Baseline | Outcome | % change from baseline | Group change Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pill Count | ||||

|

| ||||

| Control | 94(.05) | 94 (.05) | 0% | |

| t=1.1, p>.05 | F (22,1) = 12.005, p=.003* | |||

|

| ||||

| Intervention | 92(.05) | 98(.03) | 6.5% | |

| t=2.2, p=.04* | ||||

|

| ||||

| Tacrolimus Trough Levels | ||||

|

| ||||

| Control | 7.3 (3.5) | 6.4 (3.5) | 12.3% | |

| − t=1.5, p>.05 | F (22,1) = 1.4, p>.05 | |||

|

| ||||

| Intervention | 5.4 (2.8) | 5.7 (1.8) | 5.5% | |

| t= .56, p>.05 | ||||

Significantly Different (p<.05)

Adherence Change – Tacrolimus levels

Mean Tacrolimus trough levels did not differ significantly between groups either at baseline (t = 1.5, p>.05) or at study completion (t=.56, p>.05). Neither group's mean Tacrolimus trough levels changed significantly from baseline. Mean group levels were within target range (5–15 ug/L) at both measurement points. However, there was a substantive change in the standard deviation of the trough levels when post-intervention were compared to pre-intervention values. This change in the amount of statistical variability has been used as a measurement of adherence. In a study of pediatric liver transplant patients [66], a 1-point increase in the standard deviation was associated with a 1.58 increase in hazard of graft loss. In this trial, the control group standard deviation remained constant and the intervention group displayed a significant standard deviation change (Levine's test, <.05) with a full one point reduction.

Discussion

This study piloted the effectiveness of a group CBT/MI intervention on improving adherence to immunosuppressant medication in kidney transplant recipients. Significant improvement in our primary outcome measure, percent of pills taken, was demonstrated in our intervention group but not in our control condition, suggesting that this pilot adherence promotion program was successful at helping patients overcome barriers to non-adherence. The 6% increase in adherence not only has clinical significance, as it translates to about 2 doses in a two-week period (depending on the exact prescription), but also represents crossing the threshold to our a priori definition of `adherent'. Furthermore, there was indication that the amount of variance in Tacrolimus trough levels was decreased by the intervention. While there was no significant change in mean levels across treatment groups, as the means were within target range at all time points, the variability within that window decreased, suggesting more consistent medication taking.

These results are of particular note because a primary focus of the transplant nephrology team is to promote the taking of prescribed medication as directed. Despite this high level of care and attention there remains a substantive minority of patients that are non-adherent to their prescription. The clinical significance of this relatively low degree of non-adherence cannot be overestimated as renal transplant patients who are not appropriately immunosuppressed run a substantial risk of rejection. While this trial was underpowered to examine the relationship between adherence and graft rejection, the magnitude of the improvement in percent of pills taken (6% increase from baseline to follow-up in the intervention group) is also of true clinical significance. This intervention holds promise as a strategy to supplement standard care even for patients for whom traditional efforts have been unsuccessful.

The assessment of medication adherence is fraught with methodological challenges. In this pilot study we demonstrate the feasibility and possible utility of unannounced phone pill counts as an alternative technique for measuring adherence. While it is possible that participants could adjust the numbers of pills counted to conceal missed doses, we had no indication that participants were attempting to guess the numbers of pills left from missed doses or any other mental calculation required for adjusting pill counts. Additionally, while it is possible that the phone assessments are, in and of themselves, an intervention, this does not seem to be the case. The lack of change in our control condition suggests that the measurement of medication adherence in this way does not interfere with regular medication taking behavior, allowing the unannounced phone calls to serve as an unbiased assessment strategy.

While we believe these preliminary results to be meaningful, the study was conducted with a small sample from a single center, was of limited duration and because of these factors, we were unable to relate the change in medication taking to health changes or rejection markers. An additional limitation of the study is that we only partially described the psychosocial functioning of the participants. While we measured their baseline rates of depression, which were not clinically elevated or different across groups, we did not measure other potentially significant and influential psychosocial domains (e.g., coping strategies, rates of anxiety, health-related quality of life) [67–69].

The success of the intervention must also be appreciated in the context of the patient population. In this urban predominantly Black population, the reasons for non-compliance are complex and may well span systemic, social and individual parameters. However, in our preliminary work, 2 of the 3 most endorsed reasons for non-adherence were volitional. This both highlights the need for further health education in this population as well as the potential benefit of further adherence promotion activities. Future research should explore the relevant psychosocial and behavioral factors in adherence behaviors, the overall utility of unannounced phone calls as an assessment strategy, and continue to focus resources on sub-populations most in need of support services.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was partially supported by an NIDDK grant (DK089149) to Dr. Cukor, as well as NIMHD funding to Drs. Salifu and Cukor (MD006875).

Abbreviations

- (BDI)

Beck Depression Inventory

- (CBT)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- (DSM)

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- (ITBS)

Immunosuppressant Therapy Barrier Scale

- (MI)

Motivational Interviewing

- (RA)

Research Assistant

Footnotes

Disclosure:

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

D.C. and N.V.H. contributed to the study development, collected the data, performed statistical analysis, and prepared and reviewed the article. M.P., F.T. and M.S. consulted on study design and contributed to the preparation and review of the article.

References

- 1.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senst BL, Achusim LE, Genest RP, Cosentino LA, Ford CC, Little JA, Raybon SJ, Bates DW. Practical approach to determining costs and frequency of adverse drug events in a health care network. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001 Jun 1;58(12):1126–32. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.12.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiff GD, Fung S, Speroff T, McNutt RA. Decompensated heart failure: symptoms, patterns of onset, and contributing factors. Am J Med. 2003;114:625–30. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00132-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yen EF, Hardinger K, Brennan DC, Woodward RS, Desai NM, Crippin JS, Gage BF, Schnitzler MA. Cost-effectiveness of extending Medicare coverage of immunosuppressive medications to the life of a kidney transplant. Am J Transplant. 2004 Oct 1;4(10):1703–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matas AJ, Humar A, Gillingham KJ, Payne WD, Gruessner RW, Kandaswamy R, Dunn DL, Najarian JS, Sutherland DE. Five preventable causes of kidney graft loss in the 1990s: A single-center analysis1. Kidney Int. 2002 Aug 1;62(2):704–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaston RS, Hudson SL, Ward M, Jones P, Macon R. Late renal allograft loss: noncompliance masquerading as chronic rejection. Transplant Proc. 1999 Jun 30;31(4):21S–23S. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(99)00118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dobbels F, De Geest S, Van Cleemput J, Droogne W, Vanhaecke J. Effect of late medication non-compliance on outcome after heart transplantation: a 5-year follow-up. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004 Nov 30;23(11):1245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, Ojo AO, Ettenger RE, Agodoa LY, Held PJ, Port FK. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999 Dec 2;341(23):1725–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912023412303. Old 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jindel RM, Joseph JT, Morris MC, Santella RN, Baines LS. Noncompliance after kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Transplant Proc. 2003;35(8):2868–2872. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler JA, Peveler RC, Roderick P, Horne R, Mason JC. Measuring compliance with drug regimens after renal transplantation: comparison of self-report and clinician rating with electronic monitoring. Transplantation. 2004 Mar 15;77(5):786–9. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000110412.20050.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dew MA, DiMartini AF, Dabbs AD, Myaskovsky L, Steel J, Unruh M, Switzer GE, Zomak R, Kormos RL, Greenhouse JB. Rates and risk factors for nonadherence to the medical regimen after adult solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2007 Apr 15;83(7):858–73. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000258599.65257.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Didlake RH, Dreyfus K, Kerman RH, Van Buren CT, Kahanet BD. Patient noncompliance: a major cause of late graft failure in cyclosporine-treated renal transplants. Transplant Proc. 1988;20:63–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chisholm MA, Mulloy LL, Jagadeesan M, DiPiro JT. Impact of clinical pharmacy services on renal transplant patients' compliance with immunosuppressive medications. Clin Transplant. 2001;15:330–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2001.150505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butkus DE, Meydrech EF, Raju SS. Racial differences in the survival of cadaveric renal allografts: overriding effects of HLA matching socioeconomic factors. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:840–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209173271203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chisholm MA, Kwong WJ, Spivey CA. Associations of characteristics of renal transplant recipients with clinicians' perceptions of adherence to immunosuppressant therapy. Transplantation. 2007;84:1145–50. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000287189.33074.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denhaerynck K, Steiger J, Bock A, Schäfer-Keller P, Köfer S, Thannberger N, De Geest S. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Non-Adherence with Immunosuppressive Medication in Kidney Transplant Patients. Am J Transplantation. 2007 Jan 1;7(1):108–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiley DJ, Lam CS, Pollak R. A study of treatment compliance following kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 1993;55:51–56. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberger J, Geckova AM, Dijk JP, Nagyova I, Roland R, Heuvel WJ, Groothoff JW. Prevalence and characteristics of noncompliant behaviour and its risk factors in kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Int. 2005 Sep 1;18(9):1072–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schweizer RT, Rovelli M, Palmeri D, Vossler E, Hull D, Bartus Sl. Noncompliance in organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1990;49:374–377. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199002000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegal BR, Greenstein SM. Postrenal transplant compliance from the perspective of the African-Americans, Hispanic- Americans, Anglo-Americans. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1997;4:46–54. doi: 10.1016/s1073-4449(97)70016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weng FL, Israni AK, Joffe MM, Hoy T, Gaughan CA, Newman M, Abrams JD, Kamoun M, Rosas SE, Mange KC, Strom BL. Race and electronically measured adherence to immunosuppressive medications after deceased donor renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephr. 2005 Jun 1;16(6):1839–48. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeGeest S, Borgermans L, Gemoets H, Abraham I, Vlaminck H, Evers G, Vanrenterghem Y. Incidence, determinants, and consequences of subclinical noncompliance with immunosuppressive therapy in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1995;59:340–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frazier P, Davis-Ali S, Dahl K. Correlates of noncompliance among renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 1994;8:550–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenstein S, Siegal B. Compliance and noncompliance in patients with functioning renal transplant: a multicenter study. Transplantation. 1998;66:1718–1726. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199812270-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chisholm MA, Lance CE, Mulloy LL. Patient factors associated with adherence to immunosuppressant therapy in renal transplant recipients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2005;62:1775–1781. doi: 10.2146/ajhp040541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chisholm MA, Lance CE, Williamson GM, Mulloy LL. Development and validation of the immunosuppressant therapy adherence instrument (ITAS) Patient ed and counseling. 2005 Oct 31;59(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saha S, Freeman M, Toure J, Tippens KM, Weeks C. Racial and ethnic disparities in the VA healthcare system: A systematic review. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); Washington (DC): 2007. pp. 423–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker MH, Radius SM, Rosenstock IM. Compliance with a medical regimen for asthma: a test of the health belief model. Public Health Rep. 1978;93:268–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpenter CJ. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Comm. 2010;25(8):661–669. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.521906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones CJ, Smith H, Llewellyn C. Evaluating the effectiveness of health belief model interventions in improving adherence: a systematic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2014;8(3):253–269. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2013.802623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Wang T, De AK, McCarty F, Dudley WN, Baranowski T. A motivational interviewing intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake through Black churches: results of the Eat for Life trial. Am J Pub Health. 2001 Oct;91(10):1686–93. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.10.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethnicity & disease. 1998 Dec;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon EJ, Gallant M, Sehgal AR, Conti D, Siminoff LA. Medication-taking among adult renal transplant recipients: barriers and strategies. Transplant Int. 2009 May 1;22(5):534. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Constantiner M, Cukor D. Barriers to immunosuppressive medication adherence in high-risk adult renal transplant recipients. Dial and Transplantation. 2011;40:60–66. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenthal Asher D, Ver Halen N, Cukor D. Depression and nonadherence predict mortality in hemodialysis treated end-tage renal disease patients. Hemo Int. 2012 Jul 1;16(3):387–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2012.00688.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008;(Issue 2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3. Art. No.: CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Bleser L, Matteson M, Dobbels F, Russell C, De Geest S. Interventions to improve medication-adherence after transplantation: a systematic review. Transplant Int. 2009;22:780–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Low JK, Williams A, Manias E, Crawford K. Interventions to improve medication adherence in adult kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review. Nephrol Dialy Transplantat. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu204. gfu204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia MFFM, Bravin AM, Garcia PD, Contti MM, Nga HS, Takase HM, de Andrade LGM. Behavioral measures to reduce non-adherence in renal transplant recipients: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Int Urology and Nephrology. 2015:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-015-1104-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Geest S, Schäfer-Keller P, Denhaerynck K, Thannberger N, Köfer S, Bock A, Steiger J. Supporting medication adherence in renal transplantation (SMART): a pilot RCT to improve adherence to immunosuppressive regimens. Clin Transplant. 2006;20(3):359–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2006.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Russell C, Conn V, Ashbaugh C, Madsen R, Wakefield M, Webb A, Coffey D, Peace L. Taking immunosuppressive medications effectively (TIMELink): a pilot randomized controlled trial in adult kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2011;25(6):864–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2010.01358.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Russell C. Culturally responsive interventions to enhance immunosuppressive medication adherence in older African American kidney transplant recipients. Progress in Transplantation. 2006;16(3):187–195. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chisholm MA, Lance CE, Williamson GM, Mulloy LL. Development and validation of an immunosuppressant therapy adherence barrier instrument. Nephr Dialys Transplant. 2005;20:181–18. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, Dobbels F, Fargher E, Morrison V, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M. A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012 May 1;73(5):691–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson N, Nazir N, Cox LS. Unannounced telephone pill counts for assessing varenicline adherence in a pilot clinical trial. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:475–482. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S24023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bangsberg DR. Monitoring adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy in routine clinical practice: the past, the present, and the future. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):249–51. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loghman-Adham Mahmoud. Medication noncompliance in patients with chronic disease: issues in dialysis and renal transplantation. Am J Managed Care. 2003;9(2):155–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rudd P, Byny RL, Zachary V, et al. Pill count measures of compliance in a drug trial: Variability and suitability. Am J Hypertens. 1988;1:309–312. doi: 10.1093/ajh/1.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Onzenoort HAW, Verberk WJ, Kessels AGH, et al. Assessing medication adherence simultaneously by electronic monitoring and pill count in patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2009;23(2):149–154. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, Stearns H, White D, Flanagan J, Pope H, Cherry C, Cain D, Eaton L, Kalichman MO. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy assessed by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1003–1006. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0171-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalichman SC, Amaral C, Cherry C, Flanagan J, Pope H, Eaton L, White D, Kalichman M, Cain D, Detorio M, Caliendo A, Schinazi RF. Monitoring Antiretroviral Adherence by Unannounced Pill Counts Conducted by Telephone: Reliability and Criterion-Related Validity. HIV Clin Trials. 2008 Sep-Oct;9(5):298–308. doi: 10.1310/hct0905-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Chesney M, Moss A. Comparing objective measures of adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: Electronic medication monitors and unannounced pill counts. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5(3):275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ihara H, Shinkuma D, Ichikawa Y, Nojima M, Nagano S, Ikoma F. Intra - and inter-individual variations in the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus (FK506) in kidney transplant recipients—Importance of trough levels as a practical indicator. Int J Urol. 1995;2:151–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.1995.tb00444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psy Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pinsky BW, Takemoto SK, Lentine KL, Burroughs TE, Schnitzler MA, Salvalaggio PR. Transplant outcomes and economic costs associated with patient noncompliance to immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2597–2606. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nevins TE, Kruse L, Skeans MA, Thomas W. The natural history of azathioprine compliance after renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2001;60:1565–1570. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takemoto SK, Pinsky BW, Schnitzler MA, et al. A retrospective analysis of immunosuppression compliance, dose reduction and discontinuation in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2704–2711. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schäfer-Keller P, Steiger J, Bock A, Denhaerynck K, De Geest S. Diagnostic accuracy of measurement methods to assess non-adherence to immunosuppressive drugs in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:616–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychia. 2005;62:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meichenbaum D. Cognitive behaviour modification. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 1977;6(4):185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC, Aloia MS. Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behavior. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rubak S, Sandbæk A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consulting and Clinical Psychol. 2003;71(5):843. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Carney RM, Freedland KE, Steinmeyer B, Blumenthal JA, Berkman LF, Watkins LL, Freedland KE, Mohr DC, Davidson KW, Schwartz JE. Usual and unusual care: existing practice control groups in randomized controlled trials of behavioral interventions. Psychosom Med. 2011 May;73(4):323–35. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318218e1fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pollock-BarZiv SM, Finkelstein Y, Manlhiot C, Dipchand AI, Hebert D, Ng VL, Solomon M, McCrindle BW, Grant D. Variability in tacrolimus blood levels increases the risk of late rejection and graft loss after solid organ transplantation in older children. Ped Trans. 2010;14:968–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chisholm M. Enhancing transplant patients' adherence to medication therapy. Clin Transpla. 2002;16(1):30–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2002.00104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Muehrer R, Becker B. Life after Transplantation: New transitions in quality of life and psychological distress. Seminars Dial. 2005;18(2):124–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wainwright S, Fallon M, Gould D. Psychosocial recovery from adult kidney transplantation: a literature review. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8(3):233–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.1999.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]