Abstract

Objective

There is a dearth of empirical studies aimed at examining the impact of differential cultural adaptation of evidence-based clinical and prevention interventions. This prevention study consisted of a randomized controlled trial aimed at comparing the impact of two differentially culturally adapted versions of the evidence-based parenting intervention known as Parent Management Training, the Oregon Model (PMTOR).

Method

The sample consisted of 103 Latina/o immigrant families (190 individual parents). Each family was allocated to one of three conditions: (a) a culturally adapted PMTO (CA), (b) culturally adapted and enhanced PMTO (CE), and (c) a wait-list control. Measurements were implemented at baseline (T1), treatment completion (T2) and 6-month follow up (T3).

Results

Multi-level growth modeling analyses indicated statistically significant improvements on parenting skills for fathers and mothers (main effect) at 6-month follow-up in both adapted interventions, when compared to the control condition. With regards to parent-reported child behaviors, child internalizing behaviors were significantly lower for both parents in the CE intervention (main effect), compared with control at 6-month follow-up. No main effect was found for child externalizing behaviors. However, a Parent x Condition effect was found indicating a significant reduction of child externalizing behaviors for CE fathers compared to CA and control fathers at posttest and 6-month follow-up.

Conclusion

Present findings indicate the value of differential cultural adaptation research designs and the importance of examining effects for both mothers and fathers, particularly when culturally-focused and gender variables are considered for intervention design and implementation.

According to meta-analytic research, interventions informed by Parent Training (PT) principles constitute the gold standard for addressing child externalizing behaviors (Kaminski, Valle, Filene, & Boyle, 2008; Michelson, Davenport, Dretzke, Barlow, & Day, 2013). An increasing body of literature also indicates the positive impact of these interventions for reducing some types of child internalizing problems (Forgatch, Patterson, DeGarmo, & Beldavs, 2009; Perrino et al., 2014).

Relevant programs of prevention research with PT-informed interventions have been implemented with underserved Latina/o populations (Gonzales et al., 2012; Martinez & Eddy, 2005; Prado et al., 2007). However, Latinas/os continue to have limited access to culturally relevant evidence-based mental health interventions (Alegría, Mulvaney-Day, Woo, Virruell-Fuentes, 2012; Baker, Arnold, & Meagher, 2011). Addressing this issue in research and service delivery is imperative. Specifically, when compared to Euro-American populations in the United States (US), Latina/o children and youth exhibit lower rates of mental health service utilization (Institute of Medicine, 2009). Low-income Latina/o immigrants are also at an increased risk for experiencing mental health problems due to the impact of considerable contextual factors such as discrimination, poverty, and cumulative trauma (Alegría et al.).

This investigation constitutes a response to the urgent need to address Latina/o mental health disparities in the US. Specifically, the main objective of this study was to empirically test the implementation feasibility and differential efficacy of two differentially culturally adapted versions of an efficacious PT intervention with at-risk Latina/o immigrant families.

Cultural Adaptation

Cultural adaptation refers to “the systematic modification of an evidence-based treatment or intervention protocol to consider language, culture, and context in such a way that it is compatible with the client’s cultural patterns, meanings, and values” (Bernal, Jimenez-Chafey, & Domenech Rodríguez, 2009, p. 362). Cultural adaptation studies have confirmed that Latina/o populations benefit from adapted PT interventions (Zayas, 2010). However, there is dearth of research designs aimed at examining the extent to which various levels of adaptation have an impact on target populations (Castro, Barrera, & Holleran Steiker, 2010).

Cultural adaptation studies have predominantly compared an adapted intervention against a control condition (Griner & Smith, 2006; Smith, Domenech Rodríguez, & Bernal, 2011). In contrast, differential cultural adaptation designs can compare rates of engagement, retention, and intervention impact according to level of adaptation (Martinez & Eddy, 2005). In this study, hypotheses were stated according to a differential cultural adaptation research design. Thus, we compared two culturally adapted versions of an efficacious parenting intervention to examine differential implementation feasibility and initial efficacy according to level of adaptation.

Impact of culturally adapted parenting interventions

Children and youth from immigrant families are at an increased risk for experiencing internalizing and externalizing problems associated with contextual stressors and parent-child cultural conflicts. For example, developmental studies with Latina/o immigrant families have documented that parenting practices informed by high expectations of the cultural value of respeto (i.e., respect), may put children at risk for increased anxiety due to rigorous expectations placed on children by caregivers (Calzada et al., 2015). However, it is important to highlight that such high expectations correspond to Latina/o parents’ desire to raise children according to cultural values that emphasize personal integrity and a commitment to family (Calzada et al.). Thus, culturally adapted evidence-based interventions represent important alternatives for Latina/o immigrant parents seeking to inform their parenting practices according to relevant cultural values and traditions, while ensuring that such cultural emphasis does not lead to increased risk for child internalizing and externalizing problems (Smokowski, David-Ferdon, & Bacallao, 2009).

Parent Management Training, the Oregon Model

Parent Management Training, the Oregon Model (PMTO®) is a clinical and preventive family intervention that has been evolving over the course of more than 40 years. The PMTO intervention is based on a model of social interaction learning and coercion theory (Forgatch, Patterson, & DeGarmo, 2005). The PMTO intervention has the following main goals: (a) promote parent-child positive involvement, (b) help children develop pro-social skills (c) decrease children’s deviant behavior with effective discipline, (d) enhance parental supervision, and (e) help family members negotiate agreements (i.e., problem solving). The efficacy of the PMTO intervention has been demonstrated in multiple randomized studies, including a 9-year longitudinal investigation with low-income Euro-American families (Forgatch & Kjøbli, 2016).

Cultural adaptation of PMTO for Latina/o populations

PMTO was selected for our program of prevention research based on the cultural fit between the intervention’s core components and salient cultural values and parenting practices of Latina/o immigrant parents. Specifically, Domenech Rodríguez et al. (2011) implemented an exploratory study in Utah with 45 families exposed to the first culturally adapted version of the PMTO intervention for Spanish speaking Latina/o immigrants. This original adaptation was titled “CAPAS: Criando con Amor, Promoviendo Armonía y Superación” (Raising Children with Love, Promoting Harmony and Self-Improvement). Whereas efficacy findings on this investigation have yet to be reported, qualitative reports from parents indicated high participant satisfaction with the adapted intervention (Domenech Rodríguez et al.). In addition to PMTO studies in the US, exploratory investigations in central (Baumann, Domenech Rodríguez, Amador Buenabad, Forgatch, & Parra-Cardona, 2014) and northern Mexico, have also provided qualitative data indicating the acceptability and relevance of the PMTO intervention for Mexican samples.

The CAPAS intervention was adapted following the tenets of the Ecological Validity Model (EVM; Bernal, Bonilla, & Bellido, 1995). The EVM model provides a rigorous guide to researchers to culturally adapt evidence-based interventions according to the following dimensions: (a) language, (b) persons, (c) metaphors, (d) content, (e) concepts, (f) goals, (g) methods, and (h) context. The majority of the original PMTO components were adapted by Domenech Rodríguez and colleagues (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2011), with two additional components adapted by researchers conducting PMTO implementation in Mexico (Baumann et al., 2014). Our research group expanded the CAPAS intervention by adding an increased focus on cultural and contextual issues. This intervention is known as CAPAS-Enhanced. A detailed description of both adapted interventions is presented in the methods section.

The Current Study

This investigation was implemented according to principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR). Thus, after co-developing with community leaders the research design, we collected qualitative data from Latina/o immigrant parents (n = 83) to culturally inform the CAPAS adapted interventions. As a result of this process, community representatives requested us to prioritize a focus on first-generation, Spanish speaking Latina/o immigrants, due to the extremely low availability of prevention interventions available to this population. The focus on this target population also corresponded with findings identified in health disparities research indicating that Latina/o immigrants experience considerable contextual barriers to access high quality mental health services in the US (HHS, 2011). Further, despite the fact that individuals of Mexican descent accounted for 75% of the US Latino population from 2000 to 2010 (Updegraff & Umaña-Taylor, 2015), epidemiological studies indicate that Mexican immigrants and US-born Mexican Americans are at high risk for experiencing a broad range of psychiatric disorders (Orozco, Borges, Medina-Mora, Aguilar-Gaxiola, & Breslau, 2013).

Differential cultural adaptation research design

In this study, parents were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: (a) the CAPAS-original intervention (CA), (b) a culturally enhanced version of the CAPAS intervention (CE), and (c) wait-list control. The overall objective of the investigation was to empirically test the differential implementation feasibility and initial efficacy of the two culturally adapted interventions. The study’s hypotheses were as follows: (a) compared to parents in the CA intervention, parents in the CE intervention would report higher levels of overall satisfaction with the adapted intervention due to the increased focus on culture and context, (b) compared to parents in the control condition, parents assigned to either the CA or CE intervention would report higher statistically significant improvements in their quality of parenting practices and reductions in children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors; (c) all intervention gains on parenting practices for the CA and CE groups would be maintained through the 6-month follow-up; (d) indicators of implementation feasibility for the CE group would be significantly higher than the CA group; and (e) CE participants would report higher statistically significant improvements in parenting practices and reductions of children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors compared to CA parents.

Method

Participants

Specific screening procedures were guided by the prevention focus of this investigation

Thus, one focal child (FC) per family was identified if the following inclusionary criteria were met: (a) between ages 4 and 12, (b) English speaking, Spanish speaking or bilingual, (c) attending kindergarten or elementary school, and (d) no documentation of active sexual abuse. Bird and colleagues’ screening measure (2001) was utilized to categorize potential participating children according to level of severity of behavioral problems. Children were selected for this study only if parents reported symptoms in the mild-to-moderate categories (levels 1 and 2). This study received institutional review board approval.

Eligibility criteria for parents included: (a) living in single or two-parent families at the time of the study, (b) identified themselves as first generation Latina/o or Hispanic, (c) Spanish speaking, (d) 18 years of age or older, and (e) reported financial adversity as confirmed by a family income not higher than 40% of HHS poverty guidelines. If individuals not meeting the full eligibility criteria expressed a need for mental health services, they were referred to the mental health organizations represented by our research partners. The detailed demographic characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic information

| CAPAS (CA) | CAPAS-Enhanced (CE) | Control Group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family Characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Participating Families | 36 | 35 | 32 |

| Annual Family Income | |||

| $10,000–20,000 | 41.7% | 22.9% | 25.0% |

| $21,000–30,000 | 25.0% | 34.3% | 37.5% |

| $31,000–40,000 | 11.1% | 22.9% | 15.6% |

| Greater than $40,000 | 13.9% | 11.4% | 12.5% |

| Average Number of Children in Householda | 2.69 (±0.98) | 2.63 (±1.11) | 3.10 (±1.08) |

| Average Age of Childrena | 9.44 (±3.35) | 8.66 (±2.85) | 9.16 (±3.18) |

| Gender of Children | 66 | 64 | 59 |

|

| |||

| Female | 14 | 18 | 17 |

|

| |||

| Male | 22 | 17 | 15 |

|

| |||

| Individual Characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Participating Individuals | 66 | 64 | 59 |

| Mothers | 36 | 35 | 32 |

| Fathers | 30 | 29 | 27 |

| Country of Origin (Mexico) | 59 | 57 | 55 |

| Average Parent Agea | 35.97 (±4.83) | 36.97 (±6.48) | 36.52 (±5.29) |

| Average Years Living in USa | 15.04 (±4.88) | 14.11 (±5.48) | 14.80 (±5.72) |

| Average Years of Educationa | 9.38 (±3.08) | 8.72 (±3.28) | 7.87 (±2.48) |

Differences in average parent age, parents’ years living in the US, average age of target children, and number of children per household were not statistically significant, F(8, 182) = 0.828, p = .579; Wilk’s Λ = .931, partial η2 = .035. Differences in gender of target child across conditions were not statistically significant, χ2 (df=2) = 2.467, p = .291.

Recruitment

Recruitment strategies targeted key community settings with high Latino presence such as faith-based organizations, health care settings, and mental health offices. Participating parents also provided referrals by word-of-mouth. From initial recruitment, 139 families were screened for eligibility. Thirty six families were excluded from the study; 3 families declined participation (8.3%), 4 families had scheduling conflicts (11.1%), 3 families relocated or could not be reached (8.3%), and 26 (72.2%) families did not meet eligibility criteria. Specifically, 15 families were not eligible due to children exhibiting severe externalizing behaviors. Eleven families were not eligible due to parents’ characteristics (e.g., parents were not Latino immigrants).

Enrolled participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: (a) 36 families to the CAPAS-original intervention (CA), (b) 35 families to the CAPAS-enhanced intervention (CE), or (c) 32 families to the wait-list control group. Computer-generated randomization involved blocking on recruitment cohort (1–4) and age of the target child –younger (5–8) vs older (9 and above). The sample size of 103 families was chosen to provide .80 power to detect medium-sized differences (d = 0.5) at 2-tailed p < .05 comparing the two intervention conditions with the control condition, using 3-level multilevel modeling (3 time points at level 1, parents at level 2, and family at level 3) with randomization at level 3. Power analysis assumed a range of intraclass correlation coefficients at level 1 (time) from .3 to .6. Optimal Design software was used for power estimation (Spybrook et al., 2011). The description of the flow of participants through the study is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participating families through each stage of the randomized trial

Overview of Intervention Procedures

Participants in the CA and CE conditions received 12 weekly sessions, 2 hours in length, including 8 to 12 parents and two facilitators. Equivalency was planned to ensure similar dosage to all participants in both adapted conditions. Participants assigned to the wait-list condition were offered the CA intervention after all follow-up assessments (T3) for both intervention conditions were completed for each cohort of the study. One team of interventionists was assigned to each intervention condition. Each team consisted of one clinical social worker and one professional affiliated with a university extension unit. All data collectors were members of the target community. Parents were offered the parenting interventions at no cost and were compensated $30 at baseline (T1), $40 at intervention completion (T2), and $50 at 6-month follow-up (T3).

Differential culturally adapted versions of PMTO

A pilot study was implemented to test and refine measures, curricula, and intervention delivery procedures associated with the two culturally adapted versions of the PMTO intervention (Author, 2012). All research activities were implemented in close collaboration with a leading mental health services agency and the largest faith-based organization in the area.

The original culturally adapted intervention (i.e., CAPAS-Original, CA) consists exclusively of the culturally adapted PMTO core components (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2011). Our research group expanded the CAPAS intervention by adding an increased focus on cultural and contextual issues identified as salient by participants in the qualitative study. This intervention, known as CAPAS-Enhanced (CE), consists of all the sessions of the CA intervention focused on the core components of the original PMTO intervention. In addition, two culture-specific sessions focus on the ways in which immigration challenges and biculturalism are likely to influence parenting experiences in Latina/o immigrant families. Further, the applied components of the PMTO intervention were carefully tailored according to cultural and contextual experiences reported by parents as having an important impact on their parenting practices. For example, in the session focused on family problem solving, parents were presented with research findings describing how acculturation gaps between parents and children can result in parent-child conflicts. This knowledge helped to normalize the role of culture on this type of family problems. Role plays were also modified according to this approach. For example, CE interventionists would ask participants to engage in limit-setting role plays by pretending they had just arrived home after a long working day in which they had experienced discrimination from non-Latina/o co-workers (e.g., parent being called a ‘wetback’). This level of detailed contextual tailoring was not implemented in the CA intervention, unless a specific situation was reported by a parent with the request to address it in the group.

In addition to the scientific relevance inherent to differential cultural adaptation designs (Barrera, Castro, Strycker, & Toobert, 2013), the increased level of cultural contextual tailoring in the CE intervention constitutes a response to scholars highlighting the need to explicitly address issues of discrimination and contextual adversity in prevention research with underserved ethnic minority populations (Unger, 2015).

Intervention equivalency

Because two culture-specific sessions were added to the original CAPAS curriculum in the CE intervention, two booster practice sessions on parenting skills were added to the CA intervention to ensure equivalency between interventions. Specifically, the first booster practice session in the CA intervention (curriculum session # 6) was offered following the session on skills encouragement, which centers on using motivational approaches and behavior modeling to help children gain mastery of new behaviors (e.g., brushing teeth on their own). The second booster practice session (curriculum session # 9) was offered after parents were exposed to the session on limit setting and discipline. The goal of this booster session focused on problem solving specific challenges that parents experienced when implementing the new parenting skills at home.

Both adapted interventions consisted of 11 sessions and one final gathering that consisted of a celebration dinner followed by a focus group interview to obtain qualitative narratives of the participants’ perceived satisfaction with individual intervention components of both adapted interventions. A total of 8 parenting groups were implemented in 4 cohorts, with each cohort lasting 3 months (12 parenting sessions). A more detailed description of the process of adaptation and content of both adapted interventions can be found in Author et al. (2012).

Intervention Fidelity

Two five-day intensive trainings were led by the first and fourth author, followed by a two-day booster training at the completion of the pilot study. The first author is a certified PMTO specialist and co-facilitated all intervention sessions in the pilot study by providing pre-session coaching and ongoing training.1 For the randomized phase of the study, he also attended all initial sessions, sessions specified for fidelity ratings in PMTO trials, and booster sessions aimed at addressing challenges expressed by parents as they implemented PMTO skills with their children. Live supervision and videos for the remainder of the sessions were reviewed by the first author to ensure fidelity of implementation on key PMTO dimensions (Forgatch et al., 2005). The first author consulted via video-conferencing with one of the original developers of PMTO throughout the implementation of the study to increase fidelity to the model.

Assessment Procedures and Measures

Data were gathered through comprehensive quantitative assessments implemented at T1, T2, and T3. Assessments were administered by university-extension research assistants, who were also residents of the target community. Assessments were completed at the participants’ homes or at a site of their choice (e.g., local church). In the case of two-parent families, each parent completed a separate, confidential survey. One child per family was identified as the focal child (FC) according to eligibility criteria. Parents were given a choice to complete the measures in Spanish or English. All participants chose to complete measures in Spanish.

Quantitative assessment procedures began by obtaining written consent and addressing questions related to intervention goals and assessment procedures. Verbal assent was obtained from children seven years old or older. Parents then separately completed the demographic questionnaire. In the case of literacy limitations, the research assistant invited the parent into a separate room where the instrument was administered verbally and privately. This procedure was used to prevent data contamination. Assessments consisted of self-report questionnaires which measured parental perceptions of the outcomes under study (i.e., parenting skills and child internalizing and externalizing behaviors).

Session satisfaction

Participants completed a weekly session satisfaction questionnaire (Forgatch et al., 2005) that has been used in several PMTO randomized trials. The 5-point questionnaire consists of a Likert-type scale that measures level of satisfaction with each individual intervention session (1= not at all satisfied, 2 = very little, 3 = some, 4 = quite a lot, 5 = very much). The anonymous form does not ask for gender identification by the parent. With the exception of one parenting cohort (α = .67), Cronbach alphas ranged from α = .86 to α = .89.

Child outcomes

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) measures parental perceptions of child behavioral problems and is completed by each parent independently. The instrument has been normed on children 4 to 16 years of age and yields standardized scores on two broad band subscales concerning externalizing and internalizing behavior, and a total problems score. Items describe children’s internalizing/externalizing behaviors on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 = not true to 2 = very true or often true. Scale scores are summed with higher scores indicating more problematic behavior. The CBCL has robust validity and reliability as confirmed by several studies including Latina/o populations. Cronbach alphas for the 38-item internalizing subscale were α = .85 and α = .81 for mothers and fathers, respectively. Reliabilities of the 35-item externalizing subscale were α = .89 and α = .88 for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Parenting outcomes

Five parenting measures that had been used in previous studies with Latina/o populations were administered (Domenech Rodríguez, Franceschi Rivera, Sella Nieves, & Félix Fermín, 2013; Martinez & Eddy, 2005). All measures used a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1= never to 5 = always. For each scale, individual items were averaged to produce a mean score with higher scores indicating higher levels of functional parenting practices. The skills encouragement, limit setting, supervision, and effective discipline scales were adapted from Martinez and Eddy (2005) in a collaborative process between bilingual and bicultural PMTO-trained researchers (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2013). Integrating this expert panel of bilingual parenting researchers was essential to ensure linguistic appropriateness and content validity of the measures.

Skills Encouragement

This measure consists of 24 items to assess active expression of positive reinforcement (e.g., you reward the positive behavior of your child) as well as various forms of parental encouragement (e.g., you help your child to accomplish a difficult task). Cronbach alphas were α = .87 and α = .85 for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Discipline – Limit-setting

Discipline was measured with six items aimed at examining non-coercive limit setting strategies in response to child misbehavior (e.g., you remove a privilege from your child, you give your child a time out). Cronbach alphas were α = .63 and α = .68 for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Supervision

The measure consists of 16 items assessing parental monitoring and supervision (e.g., How often do you ask your child about his/her school activities?). Items also include knowledge of children’s friends and children’s activities (e.g., How often does your child spend time with friends that you do not know?). Cronbach alphas were α = .69 and α = .71 for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Family Problem Solving

This 18-item measure was adapted from the scale developed by Domenech Rodríguez, Villatoro Velázquez, and Gutiérrez López (2007). The scale consists of one sub-scale focused on positive family problem solving behaviors (e.g., When I need to solve a problem with my child, all family members propose potential solutions to the problem). An additional scale consists of reverse-scored items aimed at assessing negative problem solving (e.g., When I have a problem with my child, I avoid talking about it with him/her). Cronbach alphas were α = .88 and α = .87 for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Positive Involvement

This measure was adapted using a Spanish translation of the Involvement Subscale from the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Shelton, Frick, & Wooton, 1996) with Spanish speaking families (Donovick & Domenech Rodríguez, 2008). The measure consists of 10 items focused on examining frequency of involvement with children in a variety of activities (e.g., How often do you volunteer for activities that involve your children?). Cronbach alphas were α = .81 and α = .84 for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Means and standard deviations for all outcome measures are listed in Table 2 by parent, condition, and assessment period. Because the two CBCL child behavior outcomes had substantial positive skew, log-transformations of these variables were used for analysis. Both original and transformed variables are included in Table 2. There were no significant condition differences on outcomes at pre-intervention. The correlation matrix of all outcome variables at all three assessment points are in Table 3.

Table 2.

Outcome variables: Means and standard deviations by condition, parent, and time

| Mothers

|

Fathers

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | 6-Mo FU | Pre | Post | 6-Mo FU | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Skill Encouragement | ||||||||||||

| CAPAS Enhanced | 3.40 | 0.51 | 3.89 | 0.41 | 3.85 | 0.41 | 3.37 | 0.49 | 3.88 | 0.50 | 3.92 | 0.46 |

| CAPAS Adapted | 3.46 | 0.43 | 3.83 | 0.40 | 3.70 | 0.31 | 3.41 | 0.51 | 3.68 | 0.47 | 3.67 | 0.47 |

| Control | 3.45 | 0.47 | 3.44 | 0.36 | 3.57 | 0.32 | 3.32 | 0.42 | 3.36 | 0.43 | 3.40 | 0.36 |

| Supervision | ||||||||||||

| CAPAS Enhanced | 4.01 | 0.36 | 4.25 | 0.31 | 4.29 | 0.28 | 3.83 | 0.46 | 4.12 | 0.37 | 4.22 | 0.38 |

| CAPAS Adapted | 4.07 | 0.40 | 4.20 | 0.30 | 4.20 | 0.32 | 3.98 | 0.33 | 4.14 | 0.37 | 4.11 | 0.43 |

| Control | 4.08 | 0.36 | 4.01 | 0.28 | 3.97 | 0.33 | 3.85 | 0.46 | 3.90 | 0.41 | 3.93 | 0.40 |

| Family Problem Solving | ||||||||||||

| CAPAS Enhanced | 3.39 | 0.49 | 3.87 | 0.54 | 3.91 | 0.53 | 3.42 | 0.64 | 3.91 | 0.47 | 4.09 | 0.51 |

| CAPAS Adapted | 3.50 | 0.64 | 3.84 | 0.44 | 3.87 | 0.38 | 3.45 | 0.59 | 3.86 | 0.60 | 3.76 | 0.58 |

| Control | 3.46 | 0.65 | 3.44 | 0.53 | 3.46 | 0.56 | 3.29 | 0.57 | 3.41 | 0.39 | 3.51 | 0.39 |

| Positive Involvement | ||||||||||||

| CAPAS Enhanced | 3.63 | 0.63 | 3.97 | 0.58 | 4.03 | 0.48 | 3.29 | 0.71 | 3.70 | 0.60 | 3.91 | 0.55 |

| CAPAS Adapted | 3.75 | 0.64 | 4.08 | 0.50 | 4.17 | 0.43 | 3.40 | 0.66 | 3.71 | 0.60 | 3.72 | 0.66 |

| Control | 3.84 | 0.53 | 3.77 | 0.42 | 3.65 | 0.53 | 3.41 | 0.68 | 3.39 | 0.50 | 3.49 | 0.53 |

| Discipline - Limit-setting | ||||||||||||

| CAPAS Enhanced | 3.58 | 0.52 | 3.95 | 0.43 | 3.95 | 0.45 | 3.30 | 0.59 | 3.79 | 0.62 | 3.80 | 0.64 |

| CAPAS Adapted | 3.47 | 0.58 | 3.79 | 0.45 | 3.83 | 0.42 | 3.52 | 0.71 | 3.66 | 0.44 | 3.59 | 0.58 |

| Control | 3.51 | 0.57 | 3.37 | 0.41 | 3.43 | 0.54 | 3.29 | 0.62 | 3.25 | 0.45 | 3.33 | 0.50 |

| CBCL Internalizing | ||||||||||||

| CAPAS Enhanced | 14.14 | 8.53 | 8.46 | 6.83 | 7.32 | 5.92 | 9.93 | 5.82 | 5.97 | 4.75 | 3.75 | 3.69 |

| CAPAS Adapted | 12.06 | 7.54 | 9.36 | 5.71 | 7.92 | 6.69 | 13.33 | 7.95 | 7.83 | 6.53 | 6.97 | 4.70 |

| Control | 13.40 | 7.61 | 10.22 | 6.12 | 9.77 | 7.15 | 11.86 | 6.28 | 10.21 | 6.66 | 9.62 | 11.63 |

| CBCL Externalizing | ||||||||||||

| CAPAS Enhanced | 13.60 | 8.27 | 9.14 | 7.02 | 8.03 | 6.56 | 10.38 | 6.43 | 5.55 | 4.47 | 3.42 | 4.11 |

| CAPAS Adapted | 10.44 | 5.93 | 9.62 | 6.18 | 7.80 | 7.09 | 11.90 | 8.42 | 7.60 | 5.95 | 6.73 | 6.20 |

| Control | 12.53 | 8.23 | 9.13 | 6.11 | 9.74 | 6.87 | 10.68 | 7.39 | 8.50 | 6.57 | 9.44 | 10.31 |

| CBCL Internalizing (log) | ||||||||||||

| CAPAS Enhanced | 2.51 | 0.72 | 1.96 | 0.81 | 1.83 | 0.83 | 2.23 | 0.64 | 1.69 | 0.77 | 1.23 | 0.86 |

| CAPAS Adapted | 2.38 | 0.68 | 2.16 | 0.67 | 1.94 | 0.74 | 2.49 | 0.63 | 1.88 | 0.84 | 1.86 | 0.74 |

| Control | 2.51 | 0.61 | 2.23 | 0.71 | 2.16 | 0.70 | 2.40 | 0.60 | 2.22 | 0.68 | 1.92 | 0.97 |

| CBCL Externalizing (log) | ||||||||||||

| CAPAS Enhanced | 2.47 | 0.77 | 2.06 | 0.77 | 1.85 | 0.95 | 2.19 | 0.83 | 1.62 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 0.92 |

| CAPAS Adapted | 2.24 | 0.75 | 2.17 | 0.66 | 1.86 | 0.85 | 2.32 | 0.80 | 1.86 | 0.88 | 1.73 | 0.86 |

| Control | 2.40 | 0.69 | 2.07 | 0.83 | 2.11 | 0.84 | 2.18 | 0.86 | 1.98 | 0.81 | 1.88 | 1.09 |

N= 103 mothers (35 Capas Enhanced, 36 CAPAS Adapted, 32 Control); 87 fathers (30 CAPAS Enhanced, 29 CAPAS Adapted, 28 Control).

Descriptive statistics were calculated on the full dataset, after EM estimation of missing values; there were no significant differences from statistics calculated on nonmissing data.

No condition differences were found on the set of pre-intervention measures (F(28, 142) = 0.749, p = .579; Wilk’s Λ = .759, partial η2 = .129) or on any individual variable.

Table 3.

Outcome variables : Correlation Matrix

| Sk0 | Su0 | PS0 | Inv0 | Dis0 | Int0 | Ext0 | Sk6 | Su6 | PS6 | Inv6 | Dis6 | Int6 | Ext6 | Sk12 | Su12 | PS12 | Inv12 | Dis12 | Intl12 | Ext12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Sk0 | .39 | .40 | .65 | .66 | .35 | −.16 | −.15 | .35 | .38 | .38 | .37 | .09 | .15 | .02 | .36 | .21 | .36 | .35 | .09 | −.21 | −.22 |

| Su0 | .42 | .12 | .37 | .54 | .27 | −.16 | −.22 | .27 | .48 | .21 | .38 | .03 | −.20 | −.06 | .13 | .41 | .16 | .20 | −.01 | −.18 | −.16 |

| PS0 | .54 | .26 | .28 | .56 | .42 | −.31 | −.18 | .33 | .32 | .52 | .32 | .08 | .09 | .05 | .33 | .24 | .53 | .30 | .13 | −.20 | −.13 |

| Inv0 | .68 | .46 | .59 | .34 | .39 | −.24 | −.18 | .27 | .38 | .33 | .59 | .19 | .07 | −.03 | .17 | .32 | .28 | .40 | .09 | −.20 | −.13 |

| Dis0 | .35 | .38 | .38 | .43 | .08 | .02 | .09 | .17 | .18 | .23 | .16 | .39 | .07 | .09 | .23 | .12 | .27 | .22 | .37 | −.03 | −.02 |

| Int0 | −.22 | −.19 | −.07 | −.14 | .22 | .44 | .67 | −.25 | −.16 | −.23 | −.29 | −.03 | −.09 | .03 | −.18 | −.16 | −.17 | −.19 | .04 | .46 | .27 |

| Ext0 | −.23 | −.23 | −.08 | −.17 | .16 | .68 | .48 | −.18 | −.15 | −.20 | −.16 | .04 | .02 | .21 | −.11 | −.13 | −.13 | −.08 | .14 | .39 | .57 |

| Sk6 | .37 | .20 | .25 | .34 | .25 | −.29 | −.27 | .42 | .65 | .59 | .62 | .46 | −.10 | .01 | .62 | .46 | .56 | .51 | .37 | −.38 | −.30 |

| Sup6 | .19 | .37 | .26 | .32 | .30 | −.08 | −.06 | .37 | .27 | .53 | .68 | .29 | −.15 | −.01 | .55 | .66 | .50 | .55 | .29 | −.24 | −.19 |

| PS6 | .30 | .25 | .45 | .37 | .19 | −.23 | −.25 | .66 | .33 | .38 | .60 | .39 | −.01 | .08 | .49 | .35 | .74 | .52 | .38 | −.38 | −.26 |

| Inv6 | .36 | .27 | .36 | .57 | .28 | −.07 | −.13 | .52 | .47 | .60 | .18 | .38 | −.07 | −.02 | .33 | .47 | .47 | .62 | .24 | −.28 | −.20 |

| Dis6 | −.04 | .04 | −.11 | .01 | .43 | .09 | .13 | .42 | .22 | .15 | .17 | .24 | −.05 | .14 | .27 | .28 | .44 | .43 | .59 | −.21 | −.07 |

| Int6 | −.04 | −.14 | .03 | −.05 | .15 | .14 | .06 | −.07 | −.05 | −.15 | .05 | .10 | .38 | .52 | −.12 | −.10 | −.03 | −.03 | −.12 | .06 | .00 |

| Ext6 | −.03 | −.06 | .10 | −.02 | .17 | .08 | .03 | −.07 | −.03 | −.12 | −.06 | .12 | .72 | .45 | .01 | .01 | .02 | −.10 | .07 | .10 | .26 |

| Sk12 | .30 | .11 | .25 | .20 | .15 | −.20 | −.12 | .65 | .33 | .51 | .41 | .28 | −.07 | −.13 | .23 | .37 | .54 | .47 | .49 | −.30 | −.19 |

| Su12 | .22 | .39 | .22 | .24 | .27 | −.14 | −.12 | .38 | .63 | .40 | .44 | .08 | −.07 | −.14 | .54 | .39 | .50 | .56 | .39 | −.23 | −.20 |

| PS12 | .28 | .11 | .51 | .27 | .13 | −.24 | −.18 | .49 | .31 | .66 | .49 | .04 | −.12 | −.12 | .73 | .55 | .25 | .67 | .53 | −.25 | −.39 |

| Inv12 | .29 | .19 | .34 | .41 | .25 | −.14 | −.13 | .47 | .42 | .53 | .69 | .15 | .05 | −.07 | .68 | .61 | .72 | .29 | .57 | −.32 | −.26 |

| Dis12 | −.12 | .08 | −.10 | .02 | .36 | .02 | .13 | .32 | .25 | .12 | .12 | .65 | −.04 | −.03 | .50 | .29 | .30 | .36 | .10 | −.25 | −.09 |

| Intl12 | −.16 | −.14 | −.03 | −.09 | .04 | .50 | .43 | −.38 | −.20 | −.31 | −.19 | −.06 | .16 | .12 | −.40 | −.33 | −.35 | −.33 | −.24 | .50 | .64 |

| Ext12 | −.07 | −.09 | .09 | .01 | .19 | .41 | .54 | −.34 | −.15 | −.30 | −.17 | −.03 | .07 | .12 | −.39 | −.25 | −.29 | −.30 | −.10 | .77 | .49 |

Note: Correlations between mother-report scores are in the upper right triangle; correlations between father-report scores are in the lower left triangle; the diagonal contains correlations between mother- and father-reported scores; these are underlined for readability.

Sk=Skill Encouragement; Sup=Supervision; PS=Family Problem Solving; Inv=Positive Involvement; Dis=Discipline-Limit Setting; Int=CBCL Internalizing (log); Ext=CBCL Externalizing (log). 0=Pre; 6=Post-intervention; 12= 6-month follow-up.

Correlations of .20 and above are significant at p < .05.

Data Analytic Strategy

Multilevel growth modeling (Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) was the primary analytic approach used to examine the effects of the three intervention conditions on changes in outcomes from pretest to posttest and 6-month follow-up. Family was specified at level 3, with parents (mother and father) nested within family and time of assessment (pretest, posttest, 6-month follow-up) nested within each parent. The majority of families (87 of 103) had two parents, providing sufficient variance for estimation of within-family variance across the sample. As family was the level of randomization, intervention condition (CE, CA, control) was entered as a set of dummy-coded variables at level 3. Time was centered at 6-month follow-up, in order to provide a straightforward estimate of effects at the final assessment point. Secondary analyses centered time at post-intervention to estimate condition differences at this point (Singer & Willett, 2003). Each model contained three random effects, allowing (a) the intercept or level of outcome to differ between parents within each family, (b) average intercepts (levels), and (c) time slopes to vary among families. All other parameters were estimated as fixed effects. In addition to main effects for condition and parent (mother vs father), each model also estimated Condition x Parent interactions for the intercept and time slope, allowing for tests of whether these effects differed between mothers and fathers. Age and sex of the single target child in each family were also included as control variables. To address inflation of Type I errors due to multiple outcome measures, analyses were conducted on overall composite means across parenting practices and child behavior as well as individual scale scores.

HLM7 software (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2011) was used for the analysis, with full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation of parameters. Robust standard errors were used to compute p values and confidence intervals, optimizing accuracy for moderate non-normality. Effect sizes (d) were computed for each effect, using pre-intervention pooled standard deviations in the denominator (Feingold, 2009; Raudenbush & Liu, 2001). Effect sizes were referred to the standard benchmarks of “small,” “medium,” and “large” proposed by Cohen (1988). Confidence intervals around each d were computed using methods developed by Feingold (2015). The significance of interaction effects was tested using likelihood ratio chi square tests to compare nested models. For interaction effects found to significantly improve model fit, simple slopes were computed using methods developed by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006).

All analyses were on the full intent-to-treat sample. Of the total possible 570 interviews, 56 (9.8%) were missing, apparently completely at random (Little’s MCAR χ2 (df = 382) = 153.573, p = 1.0. For outcome analyses, missing values were handled in two ways, through expectation maximization (EM) and FIML estimation (Enders, 2010); results were virtually identical, and EM estimated results are reported.

Results

Intervention Feasibility Outcomes

Intervention participation

Of the 71 families randomly assigned to the CA and CE intervention conditions, all initiated the intervention. One family allocated to the wait list condition dropped out before completing the pre-intervention assessment. Of the CA families that began the intervention, 86.6% completed 7 or more sessions, 2.7% completed 6 sessions, and 11.1% completed 1–3 sessions. Of the CE families that began the intervention, 85.7% completed 7 or more sessions, 2.8% completed 6 sessions, and 11.4% completed 1–3 sessions. Completion of a minimum of 6 sessions was considered a criterion for retention and sufficient exposure to the PMTO core components. Adopting this criterion was informed according to contextual challenges experienced by parents. Specifically, some parents (primarily fathers) reported having trouble getting away from work to attend parenting groups. Thus, they were encouraged to attend every other meeting to receive adequate exposure to the core components without putting at risk their work stability. This approach was effective as 86.6% of fathers in the CA intervention attended 6 or more sessions, compared to 79.3% of fathers in the CE intervention. Although parents who completed only 1–3 sessions were not considered retained cases due to their limited exposure to core PMTO components, these cases were included in the intent-to-treat efficacy calculations. Completion of sessions by sex of participants is reported in Figure 1.

Intervention satisfaction

Session satisfaction data were aggregated from weekly ratings of mothers’ and fathers’ satisfaction with the intervention (n = 118). Contrary to expectations, high satisfaction ratings were observed across all sessions for both intervention conditions and averaged 4.52 (SD = 0.06) in the CA intervention and 4.57 (SD = 0.05) in the CE intervention. No significant differences were found in satisfaction between interventions on any of the individual sessions focused on the PMTO core components. In addition, there was not a statistically significant difference in overall satisfaction between interventions across all four cohorts of the study, t (6) = −.670, p = .528.

Intervention Outcomes

Table 4 contains the results of 3-level multilevel models examining comparisons between the CA and CE interventions with the control group. The first panel of this table presents the gamma coefficients and associated p values at 6-month follow-up, which was defined as the intercept for these analyses. The second panel contains the coefficients for the linear time slopes. The intercept columns show the average intercept and slope levels for the control group, and the CE vs Control and CA vs Control columns show the comparisons between the intercepts and slopes for each of the two intervention conditions and the control group.

Table 4.

3-level multilevel models of parenting and child behavior outcomes regressed on time and experimental condition

| Outcome Variables | Intercept (centered at 6-month FU)

|

Linear Time Slope

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | CE vs Control | CA vs Control | Intercept | CE vs Control | CA vs Control | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| g | p | g | p | g | p | g | p | g | p | g | p | |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Parenting Practices – Overall | 3.029 | <.001 | 0.345 | <.001 | 0.312 | <.001 | 0.001 | 0.93 | 0.028 | <.001 | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Skill Encouragement | 3.675 | <.001 | 0.392 | < .001 | 0.243 | .010 | 0.003 | .840 | 0.028 | .003 | 0.008 | .350 |

| Supervision | 4.055 | < .001 | 0.364 | <.001 | 0.253 | .002 | −0.023 | .018 | 0.034 | < .001 | 0.018 | .003 |

| Family Problem Solving | 3.446 | < .001 | 0.530 | <.001 | 0.450 | <.001 | −0.016 | .370 | 0.043 | <.015 | 0.024 | <.001 |

| Positive Involvement | 3.879 | < .001 | 0.384 | <.001 | 0.522 | <.001 | −0.025 | .160 | 0.048 | <.001 | 0.045 | <.001 |

| Discipline - Limit Setting | 3.382 | <.001 | 0.615 | <.001 | 0.442 | <.001 | −0.030 | .114 | 0.041 | .001 | 0.031 | <.001 |

| Child Behavior (Log) – Overall | 1.774 | <.001 | −.298 | 0.066 | −0.203 | 0.173 | −0.027 | 0.16 | −0.027 | 0.023 | −0.010 | 0.428 |

| CBCL Internalizing (Log) | 2.038 | <.001 | −0.379 | .016 | −0.230 | .154 | −0.015 | .570 | −0.029 | .033 | −0.010 | .503 |

| CBCL Externalizing (Log) | 1.792 | <.001 | −0.217 | .261 | −0.210 | .221 | −0.017 | .569 | −0.023 | .095 | −0.008 | .531 |

| Significant Parent x Condition Interactions

|

||||||||||||

| Parent x CBCL Internalizing (Log) | −0.328 | .350 | −0.346 | .084 | 0.109 | .555 | −0.050 | .168 | −0.013 | .479 | −0.005 | .780 |

| Parent x CBCL Externalizing (Log) | −0.095 | .783 | −0.573 | .011 | 0.039 | .827 | −0.047 | .205 | −0.042 | .039 | −0.008 | .629 |

Experimental condition was specified in two dummy variables for CAPAS Enhanced (CE) and CAPAS Adapted (CA), with Control as the reference category. Models controlled for age and sex of target child. Coefficients significant at p < .05 are bolded. Model fit comparison with and without Parent x Condition interactions: Internalizing, LR chi square(df-4) = 9.488, p <.05; Externalizing, LR chi square(df=4) = 10.981, p =.027.

Table 5 contains effect sizes (d), 95% confidence intervals, and p values for condition comparisons derived from the multilevel models. The table shows condition comparisons calculated at two points of assessment – post-intervention (in the first panel) and 6-month follow-up (in the second). Effect sizes are presented for comparisons of CE vs Control, CA vs Control, and CE vs CA.

Table 5.

Effect sizes from 3-lvl MLM models of parenting and child behavior outcomes -- condition comparisons

| Outcome Variables | Between-condition differences at post intervention

|

Between-condition differences at 6-month FU

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CE vs Control | CA vs Control | CE vs CA | CE vs Control | CA vs Control | CE vs CA | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| d | 95% CI

|

d | 95% CI

|

d | 95% CI

|

d | 95% CI

|

d | 95% CI

|

d | 95% CI

|

|||||||||||||

| LCL | UCL | p | LCL | UCL | p | LCL | UCL | p | LCL | UCL | p | LCL | UCL | p | LCL | UCL | p | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Skill Encouragement | 0.470 | 0.123 | 0.795 | .006 | 0.385 | 0.123 | 0.795 | .023 | 0.085 | −0.282 | 0.486 | .610 | 0.815 | 0.511 | 1.434 | <.001 | 0.505 | 0.141 | 1.065 | .002 | 0.308 | −0.070 | 0.805 | .103 |

| Supervision | 0.422 | 0.025 | 0.895 | .010 | 0.372 | 0.025 | 0.895 | .040 | 0.047 | −0.339 | 0.455 | .774 | 0.948 | 0.682 | 1.659 | <.001 | 0.659 | 0.312 | 1.315 | .002 | 0.286 | −0.106 | 0.814 | .131 |

| Family Problem Solving | 0.432 | 0.125 | 1.022 | .021 | 0.460 | 0.125 | 1.022 | .014 | −0.030 | −0.436 | 0.362 | .857 | 0.832 | 0.536 | 1.538 | <.001 | 0.706 | 0.407 | 1.354 | <.001 | 0.124 | −0.275 | 0.584 | .483 |

| Positive Involvement | 0.139 | 0.070 | 0.833 | .315 | 0.326 | 0.070 | 0.833 | .023 | −0.187 | −0.625 | 0.109 | .169 | 0.520 | 0.288 | 1.150 | .001 | 0.706 | 0.566 | 1.390 | <.001 | 0.187 | −0.622 | 0.105 | .168 |

| Discipline - Limit Setting | 0.682 | 0.121 | 0.964 | <.001 | 0.442 | 0.121 | 0.964 | .013 | 0.241 | −0.078 | 0.670 | .123 | 1.122 | 0.863 | 1.895 | <.001 | 0.807 | 0.507 | 1.475 | <.001 | 0.316 | −0.056 | 0.832 | .089 |

| CBCL Internalizing (Log) | −0.760 | −0.549 | 0.107 | .090 | −0.595 | −0.549 | 0.107 | .188 | −0.164 | −0.370 | 0.248 | .701 | −1.447 | −0.977 | −0.098 | .016 | −0.878 | −0.128 | 0.780 | .154 | −0.573 | −0.634 | 0.211 | .330 |

| CBCL Externalizing (Long) | −0.143 | −0.670 | 0.204 | .627 | −0.260 | −0.670 | 0.204 | .298 | 0.117 | −0.346 | 0.555 | .652 | −0.409 | −1.015 | 0.282 | .261 | −0.396 | −0.932 | 0.223 | .221 | −0.011 | −0.603 | 0.583 | .971 |

| Parent x Condition interactions (Simple slopes)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CBCL Internalizing (Log) -- Mother | −0.283 | −0.620 | 0.054 | .104 | −0.223 | −0.559 | 0.114 | .200 | −0.277 | −0.838 | 0.284 | .720 | −0.538 | −1.019 | −0.057 | .031 | −0.326 | −0.804 | 0.152 | .183 | −0.211 | −0.678 | 0.256 | .378 |

| CBCL Internalizing (Log) -- Father | −0.653 | −1.013 | −0.293 | <.001 | −0.108 | −0.468 | 0.253 | .561 | −0.546 | −0.901 | −0.191 | .003 | −1.028 | −1.537 | −0.520 | <.001 | −0.173 | −0.685 | 0.338 | .511 | −0.855 | −1.359 | −0.352 | .001 |

| CBCL Externalizing (Log) -- Mother | −0.128 | −0.608 | 0.352 | .600 | −0.233 | −0.713 | 0.247 | .346 | 0.104 | −0.366 | 0.574 | .666 | −0.374 | −1.009 | 0.260 | .261 | −0.355 | −0.986 | 0.275 | .273 | −0.011 | −0.630 | 0.608 | .973 |

| CBCL Externalizing (Log) -- Father | −0.659 | −1.169 | −0.149 | .013 | −0.086 | −0.595 | 0.422 | .742 | −0.573 | −1.073 | −0.073 | .028 | −0.603 | −0.172 | 0.066 | .086 | −0.290 | −0.964 | 0.384 | .402 | −1.046 | −1.708 | −0.383. | 003 |

Note: CE = CAPAS-Enhanced; CA = CAPAS Adapted; d=Gamma/sd; sd = observed pooled sd at T1 (Feingold, 2009; Raudenbush & Lui, 2001).

Effects significant at p < .05 and associated confidence intervals are bolded.

Parenting practices

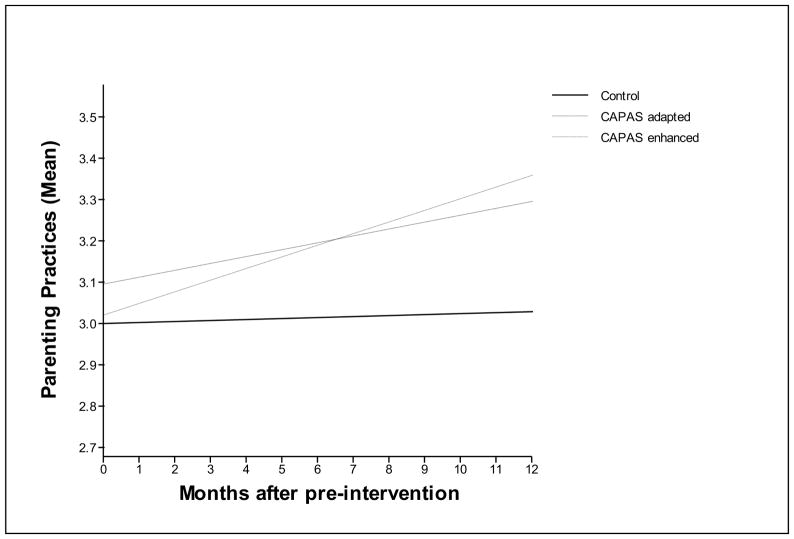

As shown in table 4, both CE and CA were significantly different from the control group at 6-month follow-up on each of the five parenting measures as well as the overall mean across the individual parenting measures. Comparisons of linear slopes showed significant differences between CE and control on the overall mean and on all specific parenting measures and between CA and control on all but skill encouragement. In all cases coefficients were positive, indicating statistically significant increases over time and higher levels at 6-month follow-up for parents in the CE and CA conditions in comparison with those in the control group. Figure 2 contains a model graph of estimated change in overall parenting practices for each of the three groups. No significant Parent x Condition interactions were found for any of the parenting measures, indicating that patterns of change were similar for both mothers and fathers.

Figure 2.

Model graph of estimated change on overall parenting practices in CE, CA, and control groups.

The effect sizes in Table 5 show that, at the post-intervention assessment, differences between CE and control were in the medium range (d = 0.40 to 0.70) and significantly higher than zero for all parenting outcomes except positive involvement. Differences between CA and control were all significant and small-to-medium in size (d = 0.30 to 0.40). Comparisons between CE and CA were very small and none was significantly different from zero.

By 6-month follow-up, differences between CE and control increased, ranging from d = 0.52 to 1.12. For four of the parenting measures – skill encouragement, supervision, family problem solving, and discipline-limit setting, effects were above the d = 0.80 threshold generally considered large. For positive involvement, the effect was a medium-sized d = 0.50. Differences between CA and control ranged from d = 0.50 to 0.80, in the medium-to-large range. Comparisons between CE and CA were in the small range (0.30 and less), and none was statistically significant.

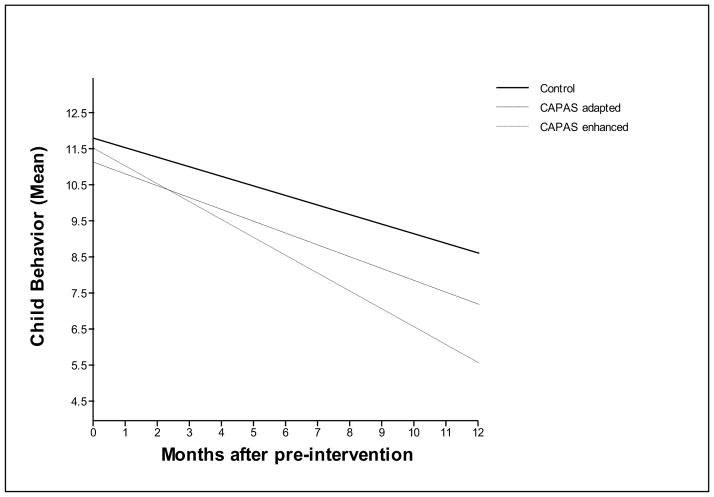

Child internalizing and externalizing behaviors

Table 4 shows a steeper decline in both overall problem behaviors and internalizing behaviors, specifically for CE versus control. By 6-month follow-up, child internalizing behaviors were significantly lower in CE compared with control. No significant differences were found for child externalizing behaviors, and no differences were found for CA versus control. Figure 3 displays a model graph of estimated change in overall child behavior problems for each of the three groups. For both internalizing and externalizing behavior outcomes, there were interactions between parent (mother vs father) and condition that significantly modified these effects according to model comparison tests. The effect sizes for simple slopes computed from these interactions are presented in Table 5.

Figure 3.

Model graph of estimated change on overall child behavior in CE, CA, and control groups.

Note: Model computation used log-transformed child behavior scores due to positive skew. For ease of interpretation, raw scores are displayed in the graph.

Reports of child internalizing behaviors were lower at posttest for CE compared with control for fathers but not mothers. However, by 6-month follow-up, child internalizing behaviors were significantly lower for CE compared with control for both parents. In addition to the CE vs control difference, CE was significantly lower than CA at both posttest (d = −0.50) and 6-month follow-up (d = −0.90) for fathers only. Differences for mothers were smaller (d < 0.30) and non-significant.

For child externalizing behaviors, no significant condition differences were found for mothers at posttest. However, for fathers, CE vs control differences were significant at posttest (d = −0.70) but not 6-month follow-up (d = −0.06). CE vs CA differences were significant at both time points – post (d =−0.60) and follow-up (d =−1.00). CA vs control differences were small (d < −0.40) and not significant for either child behavior outcome reported by mothers or fathers.

Discussion

Parenting Outcomes

In alignment with our expectations, high rates of engagement, retention, and overall participant satisfaction were observed in both adapted interventions. These findings correspond with post-intervention qualitative narratives of participants reporting high satisfaction with the core PMTO parenting components in both adapted interventions (Author, 2016). Furthermore, medium to large effect sizes indicate sustained improvements of parenting skills for participants in both adapted interventions at 6-month follow up. Contrary to our hypotheses, no statistically significant differences between the adapted interventions were observed on any of the parenting outcomes at follow up. Although unexpected, these results are valuable as they correspond with meta-analytical findings corroborating the positive impact of core parent training (PT) components across various target populations, PT interventions, and contexts (Kaminski et al., 2008; Michelson, 2013). Evidence that the specific PT core components under study had a positive impact on participants in both interventions, indicates the potential cross-cultural impact of such components when considering large-scale dissemination with populations affected by health disparities (Institute of Medicine, 2009).

Current results also support the value of conducting adaptations according to comprehensive frameworks (Bernal & Domenech Rodríguez, 2012). That is, although the CA intervention did not include culture-specific sessions, the intervention was developed according to a rigorous model that guided adaptations at multiple levels, which ensured the linguistic appropriateness and cultural relevance of the original PMTO core components. These results suggest the importance of continuing to explore the cross-cultural relevance of the core PMTO components with diverse populations in contrasting contexts. For example, high feasibility in the delivery of culturally adapted PMTO core components has been reported in studies with Mexican parents residing in Mexico (Baumann et al., 2014; Author, 2015) and with Muslim immigrant families living in Norway (Bjørknes, Kjøbli, Manger, & Jakobsen, 2012).

Child Outcomes

Findings on child outcomes partially supported our hypotheses. Specifically, a main effect for child internalizing behaviors was found for both mothers and fathers in the CE intervention. This finding is relevant because although CA parents reported gradual improvements of child internalizing behaviors over time, the slope of change did not reach statistical significance nor was there a significant difference at 6-month follow up. With regards to child externalizing outcomes, a Parent x Condition effect was observed at 6-month follow-up. Specifically, only fathers in the CE intervention reported statistically significant improvements on child externalizing behaviors at follow up.

These results are relevant as the literature indicates that Latina/o immigrant children and youth are at an increased risk for internalizing symptoms associated with immigration-related stressors such as parent-child cultural conflicts (Bámaca-Colbert, Umaña-Taylor, & Gayles, 2012). For example, Calzada and colleagues recently reported that high expectations of Mexican origin parents for children to comply with traditional cultural values such as respeto (respect), associated with authoritarian parenting practices, can place young Latina/o children at high risk for developing internalizing problems (Calzada, Barajas-Gonzalez, Huang, & Brotman, 2015). Thus, current findings are promising as they indicate that the culturally enhanced version of the PMTO intervention can effectively bolster parenting practices of Latina/o parents in culturally relevant ways, while also reducing risk for child internalizing symptomatology.

In addition, results partially supported our hypothesis with regards to child externalizing behaviors as statistically significant improvements were only observed for fathers allocated to the CE intervention. These findings raise questions regarding the role of cultural variables and gender when examining parent perceptions of children’s behaviors. For example, it may be possible that differences in parental ratings were due to contrasting levels of acculturation and parenting expectations between mothers and fathers. That is, research indicates that fathers tend to acculturate faster to US norms, values, and traditions than mothers (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010). In addition, because parenting expectations in US majority groups tend to be skewed toward valuing child independence, differences in child behavior expectations may have influenced parental reports on child externalizing behaviors for mothers and fathers (Schwartz et al.). Thus, the changes in child behaviors observed by fathers may have been sufficient according to their expectations but insufficient for mothers.

Measurement issues may potentially explain contrasting findings on child externalizing outcomes. Specifically, families were eligible to participate only if parents reported mild-to-moderate behavior problems. Thus, alternative measures of problem behaviors for non-clinical samples are likely to be better suited for future cultural adaptation prevention trials with populations resembling the characteristics of participants in this study.

CE Intervention Differential Effect

The current investigation demonstrates the relevance of conducting cultural adaptation differential research. We hypothesize that the incremental effects observed in the CE intervention may be associated with the increased focus on contextual challenges, immigration, and biculturalism. Specifically, the content of the CE intervention and method of intervention delivery were carefully refined to match day-to-day parenting challenges, as influenced by key contextual and cultural stressors. Current quantitative findings correspond with qualitative data from this study, indicating the high relevance that parents attributed to the culture-specific components of the CE intervention (Author, 2016). The results from this investigation also corroborate the approach used in efficacious parenting interventions with Latina/o immigrants, characterized by an explicit focus on immigration-related challenges and biculturalism (Martinez & Eddy, 2005; Gonzales et al., 2014; Smokowski, David-Ferdon, & Bacallao, 2009; Perrino et al., 2014; Updegraff & Umaña-Taylor, 2015). Whereas differential findings indicate an incremental effect in the CE intervention, additional research is needed to reach definitive conclusions about the impact of this level of adaptation.

Clinical Implications

This study provides empirical data with useful clinical implications. First, the similar improvements on parenting skills observed in both adapted interventions, indicate to clinicians that rigorous adaptations of efficacious parent training (PT) interventions have the potential to be perceived as relevant by diverse populations, provided that targeted parenting components are presented to clients within frameworks of contextual and cultural relevance (Bjørknes et al., 2012). With regards to contrasting findings between adapted interventions, an enhanced focus on contextual stressors, immigration, and biculturalism appeared to have an incremental effect for parents in the CE intervention. However, outcome differences were also related to differences in perceptions between fathers and mothers. Thus, clinicians should be cognizant that adapted interventions are likely to be perceived differently by mothers and fathers, as they are likely to be influenced in contrasting ways by specific cultural factors such as level of acculturation (Schwartz et al., 2010).

Study Limitations and Strengths

Findings should be considered in light of a number of study limitations. First, outcome data consisted of parental self-reports, which carry the risk of reporting bias as documented in the parenting research literature. In addition, the small sample sizes in all intervention conditions may have limited the possibility of identifying smaller intervention effects. Furthermore, because initial intervention effects on child outcomes in longitudinal prevention studies in PMTO trials have been observed at 1-year follow-up, there is a possibility that levels of change in the CA and CE interventions could have reached statistical significance with more distal measurements.

Notwithstanding current limitations, this investigation offers important contributions to the cultural adaptation literature. The most relevant refers to the fact that this study compared two differentially culturally adapted parent training interventions. As such, this investigation was subject to the challenges inherent in designs aimed at examining the relative efficacy between two treatments, which tend to produce smaller effect size estimates than traditional tests of absolute efficacy conducted in treatment versus control designs (Wampold, 2015). Thus, the identification of medium-to-large differential effect sizes on parenting and child outcomes according to intervention condition and gender, constitutes an important contribution to the cultural adaptation literature. Furthermore, current findings provide evidence documenting the need to conduct cultural adaptation according to multi-dimensional frameworks, particularly when targeting populations exposed to considerable contextual challenges. A thorough approach to cultural adaptation is likely to result in successful participant engagement and retention, satisfaction with adapted components, and positive impacts on targeted outcomes. Finally, the high retention rates of fathers in this study allowed for the identification of contrasting intervention effects between mothers and fathers. These findings are relevant as fathers continue to be underrepresented in empirical studies focused on PT interventions (Baker et al., 2011). However, it must be noted that the differential effects found for fathers could also be attributed to alternative factors not accounted for in the study design.

Conclusions and Future Directions

This investigation highlights the need for conducting additional differential cultural adaptation studies with alternative parenting interventions and target populations. Such studies should have high measurement precision of relevant cultural and outcomes variables to allow for tests of moderation and mediation effects, as well as associated mechanisms of change. Similarly, it is critical to identify culture-specific themes that are likely to enhance the cross-cultural relevance of adapted interventions when targeting multiple underserved ethnic groups (e.g., racial socialization as a way of coping with racism and discrimination). Current findings also indicate the importance of continuing to investigate the impact of PT interventions on child internalizing problems, as recently stressed by developmental and prevention researchers (Calzada et al., 2015; Perrino et al., 2014). These lines of research are necessary because there is still a need to clarify which specific internalizing child problems are most likely to be positively impacted by PT interventions (Michelson et al., 2013).

Finally, whereas this prevention study offered a contribution by investigating a strategy to address mental health disparities with a diverse sample, a sense of urgency remains when considering the large number of diverse populations that continue to be negatively impacted by widespread mental health disparities throughout the US and the world (Alegría et al., 2012).

Public Health Significance.

This study has important public health implications because it empirically demonstrates the relevance of promoting differential cultural adaptation research as an alternative to maximize the delivery of evidenced-based interventions to underserved Latina/o populations in the US.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Award Number R34MH087678 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. Supplementary funding was provided by the MSU Office of the Vice-President for Research and Graduate Studies (OVPRGS), the MSU College of Social Science, and the MSU Department of Health and Human Development. We would like to express our deep gratitude to Marion Forgatch, ISII Executive Director and Laura Rains, ISII Director of Implementation and Training, for their resolved and continuous support as we have engaged in dissemination efforts with underserved populations in the U.S.

Footnotes

The process of PMTO certification is a lengthy process that can take up to two years. Such a certification must be granted by Implementation Sciences International, Inc, or a certified implementation site. The PMTO intervention disseminated in this study closely adheres to the core components of the original PMTO intervention. However, because none of the main interventionists were certified in the delivery of the intervention, we consider the adapted interventions in this study to be PMTO-Informed.

Contributor Information

J. Rubén Parra-Cardona, Michigan State University.

Deborah Bybee, Michigan State University.

Cris M. Sullivan, Michigan State University

Melanie M. Domenech Rodríguez, Utah State University

Brian Dates, Southwest Solutions.

Lisa Tams, Michigan State University-Extension.

Guillermo Bernal, University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras.

References

- Author (2009).

- Author (2012).

- Author (2015).

- Author (2016).

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, Virruell-Fuentes EA. Psychology of Latino adults: Challenges and an agenda for action. In: Chang EC, Downey CA, editors. Handbook of race and development in mental health. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 279–306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alegría M, Vallas M, Pumariega AJ. Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;19:759–774. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bámaca-Colbert MY, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gayles JG. A developmental contextual model of depressive symptoms in Mexican-origin female adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:406–421. doi: 10.1037/a0025666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG, Strycker LA, Toobert DJ. Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:196–205. doi: 10.1037/a0027085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CN, Arnold DH, Meagher S. Enrollment and attendance in a parent training prevention program for conduct problems. Prevention Science. 2011;12:126–138. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann AA, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Amador Buenabad NG, Forgatch MS, Parra-Cardona JR. Parent Management Training-Oregon model in Mexico City: Expanding the cultural adaptation process model to integrate implementation activities. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2014;21:32–47. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Bonilla J, Bellido C. Ecological validity and cultural sensitivity for outcome research: Issues for the cultural adaptation and development of psychosocial treatments with Hispanics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:67–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01447045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptation in context: Psychotherapy as a historical account of adaptations. In: Bernal G, Domenech Rodríguez MM, editors. Cultural adaptations: Tools for evidence-based practice with diverse populations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 3–22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, Jimenez-Chafey MI, Domenech Rodríguez MM. Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2009;40:361–368. doi: 10.1037/a0016401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bird HR, Canino GJ, Davies M, Zhang H, Ramirez R, Lahey BB. Prevalence and correlates of antisocial behaviors among three ethnic groups. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:465–478. doi: 10.1023/a:1012279707372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjørknes R, Kjøbli J, Manger T, Jakobsen R. Parent training among ethnic minorities: Parenting practices as mediators of change in child conduct problems. Family Relations. 2012;61:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada E, Barajas-Gonzalez G, Huang KY, Brotman L. Early childhood internalizing problems in Mexican- and Dominican-origin children: The role of cultural socialization and parenting practices. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1041593. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Holleran Steiker LK. Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodríguez M, Villatoro Velázquez JA, Gutiérrez López ML. Solución de problemas: Escala para medir el estilo de solución de problemas en familias Mexicanas. [Problem Solving: A scale to measure problem solving style in Mexican families] Revista SESAM: Servicios de Salud Mental. 2007;11:6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodríguez MM, Baumann AA, Schwartz AL. Cultural adaptation of an evidence-based intervention: From theory to practice in a Latina/o community context. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:170–186. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovick MR, Domenech Rodríguez M. An examination of self-reported parenting Practices among first-generation Spanish-speaking Latino families: A Spanish version of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. Graduate Student Journal of Psychology. 2008;10:52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychological Methods. 2009;14:43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0014699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Confidence interval estimation for standardized effect sizes in multilevel and latent growth modeling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83:157–168. doi: 10.1037/a0037721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Kjøbli J. Parent Management Training—Oregon Model: Adapting intervention with rigorous research. Family Process. 2016 doi: 10.1111/famp.12224. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon Model of Parent Management Training. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS, Beldavs ZG. Testing the Oregon delinquency model with 9-year follow-up of the Oregon divorce study. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:637–660. doi: 10.1017/s0954579409000340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Dumka LE, Millsap RE, Gottschall A, McClain DB, Wong JJ, … Kim SY. Randomized trial of a broad preventive intervention for Mexican American adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:1–16. doi: 10.1037/a0026063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health interventions: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43:531–548. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal data analysis. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Focusing on children’s health: Community approaches to addressing health disparities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski JW, Valle LA, Filene JH, Boyle CL. A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:567–589. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Eddy JM. Effects of culturally adapted parent management training on Latino youth behavioral health outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:841–851. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.73.5.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson D, Davenport C, Dretzke J, Barlow J, Day C. Do evidence-based interventions work when tested in the “real world?” A systematic review and meta-analysis of parent management training for the treatment of child disruptive behavior. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2013;16:18–34. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco R, Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Breslau J. A Cross-national study on prevalence of mental disorders, service use, and adequacy of treatment among Mexican and Mexican American populations. 2013 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrino T, Pantin H, Prado G, Huang S, Brincks A, Howe G, Brown H. Preventing internalizing symptoms among Hispanic adolescents: A synthesis across Familias Unidas trials. Prevention Science. 2014;15:917–928. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0448-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Pantin H, Briones E, Schwartz SJ, Feaster D, Huang S, … Szapocznik J. A randomized controlled trial of a parent-centered intervention in preventing substance use and HIV risk behaviors in Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:914–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.75.6.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31(4):437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Byrk A. Hierarchichal linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM 7: Hierarchical linear and nonlinear modeling. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Liu XF. Effects of study duration, frequency of observation, and sample size on power in studies of group differences in polynomial change. Psychological Methods. 2001;6:387–401. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KK, Frick PJ, Wootton J. Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:317–329. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2503_8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Domenech Rodríguez MM, Bernal G. Culture. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2011;67:166–175. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, David-Ferdon C, Bacallao ML. Acculturation and adolescent health: Moving the field forward. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:209–214. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0183-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spybrook J, Bloom H, Congdon R, Hill C, Martinez A, Raudenbush S. Optimal Design Plus Empirical Evidence: Documentation for the “Optimal Design” software” Version 3.0. New York: W. T. Grant Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB. Preventing Substance Use and Misuse Among Racial and Ethnic Minority Adolescents: Why Are We Not Addressing Discrimination in Prevention Programs? Substance Use & Misuse. 2015;50:952–955. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1010903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ. What can we learn from the study of Mexican-origin families in the United States? Family Process. 2015;54:205–216. doi: 10.1111/famp.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]