Short abstract

An exhibition at the Science Museum, London SW7, from 1 October 2004 until 13 February 2005. Admission free www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/exhibitions/futureface/

Rating: ★★★★

The Science Museum has had to evolve as science and its relationship with the public have become more sophisticated. “Future Face” is a great example of how it has grown up—a blend of art and science that really gets you thinking about what faces are, what they mean, and what they might look like in the future. For the traditionalists there are still some texts and even a few (awesome) buttons to press—just don't expect to go home with all the answers.

The “Future Face” project is the brainchild of Sandra Kemp, director of research at the Royal College of Art, and it has taken her five years to bring together. Unlike many trendy “arts meets science” projects, where the art is simply there to “sex up” the science, this one really works because scientists and artists have been pondering the mysteries of the face in their different ways for thousands of years. Kemp has supplemented her own expertise in literature and the visual arts with material from physiognomy (the study of how facial features and expression relate to character), psychology, anatomy, medicine, and advanced imaging and digital technologies.

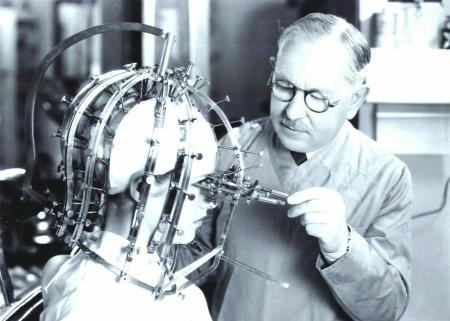

Figure 1.

The Max Factor Beauty Calibrator (1932), said to be able to measure good looks to the hundredth of an inch

Credit: PICSELECT

As you wander into the exhibition, you are confronted by a wall of about 200 mirrors—a neat motif for the entire exhibition—and a series of intricately sculpted heads showing how we think the human skull and face have evolved over millions of years. It is made clear that much of the evolution of the face is still a mystery. The development of individual sense organs, for example, helped to shape the face, but so did the ability of the whole face to convey non-verbal communication. Anatomy fans will not be disappointed—on display are a depiction of Gunter von Hagens' plastinated vascular system of the head, and a Charles Bell 1824 drawing of the muscles of the face. We learn how our thousands of different facial expressions depend on the complex co-ordination of nerves and muscles—and that even the colour, lines, and texture of the skin are a barometer of a person's age, health, and experience. But the relation of the face muscles to expressions is not completely understood—no wonder the face is such a compelling subject for both artist and scientist.

One of the most arresting sections deals with the relationship between facial appearance and thought, feeling, and consciousness. I found myself glued to the spot, gawping at a specially commissioned video installation by Christian Dorley-Brown. The piece consists of two 15-second video portraits of each subject, shown side by side, the first taken when they were age 10, the second age 20. Dorley-Brown asked them to express themselves entirely through facial expression. It was a powerful meditation on the passage of time and the loss of childhood innocence—all told through the face. Although there are many theories about how we interpret and identify faces, I was left with the impression that art has at least as much to say on the subject as science.

Figure 2.

Kaya, one of the world's first digital models

Credit: PICSELECT

Part of the exhibition is devoted to the history and development of face prostheses and facial surgery. There are the predictable portraits and photos of people with facial deformities, but some are strikingly cheerful and beautiful, as if calculated to challenge assumptions and prejudices. You can also see some of the remarkable sketches by the artist Henry Tonks, who in 1916-17 recorded the severe facial injuries of casualties from the Western Front in his work with the plastic surgeon Harold Gillies at Aldershot. Around the same time, the sculptor Francis Derwent Wood was making prosthetic masks at the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department (or “Tin Noses Shop”) at the 3rd London Hospital. We see how plastic (or aesthetic) surgery has moved on—now it is very high tech, but art still plays a big part. And these days we don't just have surgery for severe disfigurement; Britons spend more than £225m ($402m; €327m) a year on cosmetic surgery—one of the most common reasons women give for non-property loans—and 1 in 12 cosmetic surgery patients are men.

Which brings us to the big question—what will our faces look like in the future? Sandra Kemp feels that this will have less to do with genetics and evolution than a blend of modern microsurgical techniques (the first face transplant seems just round the corner) and clever digital technology (we now have digital newsreaders and digital models). But interestingly, the “perfect” and spooky digital faces on display just highlight how our natural, flawed, asymmetrical faces convey so much more about who we are and what we are feeling. In fact my own face, when digitally morphed at the press of a button to show what I would look like as a wrinkled old man, seemed to be a dramatic improvement on the current version. Worth a visit if only to press that button.