Abstract

Background

Mild to moderate depressive symptoms are common during treatment for non-metastatic breast cancer. The goal of this secondary analysis was to determine if depressive symptoms predict clinical outcomes at long-term follow-up.

Methods

From 1998-2005, we interviewed 231 women with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression who were participating in a psychosocial study 2-10 weeks post-surgery for nonmetastatic breast cancer (Stage 0-IIIb). We conducted Kaplan Meier (K-M) curves and Cox proportional hazards (PH) models to examine associations between depressive symptoms, overall survival, and disease-free survival at 8-15 year follow-up.

Results

A total of 95 women (41.1%) scored in the mild-moderately depressed range. Non-depressed women had longer overall survival (M=13.56 years; SE=.26) than those in the mild/moderate depressed group (M=11.45 years; SE=.40), Log-rank χ2(1)=4.41, p=.036. Cox PH models, adjusting for covariates, showed comparable results: mild/moderate depressive symptoms hazard ratio=2.56, [95% CI, 1.11 to 5.91], p=.027. Similar results were observed in a subsample with invasive disease (n=191). Depression category did not predict disease-free survival in the overall or invasive sample.

Conclusions

Screening and referrals for treatment of depressive symptoms, even at subclinical levels, is important early in treatment. A randomized trial is warranted to determine effects of depressive symptoms on clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, survival, depressive symptoms, recurrence, follow-up study

Introduction

For women, breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second highest cause of cancer death [1]. Survival rates for non-metastatic disease are 78% over 15 years [1]. Psychosocial factors such as depression influence mortality in cancer patients [2-7]. Estimates of prevalence of depression in women with breast cancer range as high as 37% [8]. Some individual studies [9-12] and meta-analyses [4,6,7] conclude that depressive symptoms predict higher all-cause mortality, though not breast cancer recurrence [6]. Other studies show no relationship between depressive symptoms and survival among breast cancer patients [13,14].

Discrepancies among results may be attributable to inclusion of patients at different disease stages and points in treatment. Inconsistencies may reflect differences in how depression was operationalized and where in the depression continuum cohorts were distributed. Many women treated for breast cancer report depressive symptoms that are serious but below the threshold for a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) [15]. It is valuable to know whether differences across the subclinical depressive symptom continuum influence health outcomes.

We examined early stage (0-IIIb) breast cancer patients who were free of major psychopathology, including major depressive disorder. We tested whether the magnitude of depressive symptoms reported post-surgery predicted overall survival or disease-free survival at 8-15 year follow-up (11-year median). Given the low risk of mortality and recurrence for women with non-invasive (stage 0) breast cancer, we also tested whether depressive symptoms were associated with disease endpoints in a restricted subsample of women with invasive cancer.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patients

Participants were women 2-10 weeks post-surgery for stage 0-IIIb breast cancer and enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of stress management between 1998-2005. This single center, single blind, randomized, parallel assignment efficacy trial was approved by the University of Miami (UM) Institutional Review Board (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01422551) as described in elsewhere [2]. Briefly, women were recruited via advertising and physician referrals from private practices and the UM Sylvester Cancer Center in South Florida. A total of 106 women were excluded because they were not between the ages of 21-75 years old, were not fluent in English, had stage IV breast cancer or prior cancer (except minor skin cancers), had begun adjuvant treatment, had other major medical conditions, current psychosis, active suicidality, MDD, or panic disorder, or were previously psychiatrically hospitalized.

Procedures

A total of 240 women who met entry criteria signed informed consent, completed baseline psychosocial assessments, and were randomized to either Cognitive-Behavioral Stress Management (CBSM) intervention or a 1-day psychoeducational seminar control group. At the baseline assessment, prior to randomization, 231 participants completed the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) [16], administered by a Masters-level psychologist blinded to study condition. In 2013, 8-15 years post-study enrollment (11-year median), women were re-contacted for participation in a follow-up study for which they self-reported their disease status. Participants’ medical charts were reviewed to confirm breast cancer recurrence or disease-free status. To obtain vital statistics regarding death, cause, and date of death, a linkage study was conducted with the Florida Cancer Data System (FCDS) and approved by the Florida Department of Epidemiology and Institutional Review Board of the Florida Department of Health. We supplemented data from the state registry with national online databases. The current study used data from the baseline HDRS assessment and 11-year survival and recurrence data. Demographic, medical, and treatment-related information was gathered by self-report at baseline and verified with medical chart reviews.

Depressive Symptoms

The interviewer-based 17-item HDRS [16] was administered with a Structured Interview Guide to assess depressive symptom severity over the previous week. Participants rated items on a Likert-type scale with eight items on a 0 (absent) to 4 (severe) scale and nine items on a 0 to 2 scale. Items include presence of depressed mood, anhedonia, psychomotor slowing or agitation, appetite change, and sleep difficulties. Items are summed for a total score (range 0-50). We examined total depressive symptom severity both on a continuous scale and using a clinical cutoff [17] to classify women into a mild/moderate depressive symptom group (HDRS score > 7) vs. a low depressive symptom group (HDRS score ≤ 7). A final categorization[18] sub-divided women in the former group into those with mild (HDRS=8-16) versus moderate (HDRS=17-23) levels. Test reliability was adequate (α = .78).

Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS; version 21.0) was used to conduct time-to-event analyses and investigate differences in baseline HDRS depressive symptoms and time to two clinical disease endpoints at 8-15 year follow-up: all-cause mortality and breast cancer recurrence. Overall survival time and disease-free interval were calculated as the time from randomization (2-10 weeks post-surgery) to event. Data were screened for outliers and non-normality. The Proportionality Hazards Assumption was met for all regressions. Data were censored for women who did not have a death or recurrence at the time of follow-up, were lost to follow-up, or had previously dropped out of the study. Data were right censored and met the assumption of non-informative censoring [19].

Chi-square tests and one-way ANOVAs determined any baseline differences in demographic, medical, and treatment-related variables between mild/moderate versus low depressive subgroups. Kaplan-Meier (K-M) survival curvesa were plotted to determine whether women classified with mild/moderate versus low depressive symptoms differed on clinical disease endpoints at 8-15 years. Significance of log-rank tests were interpreted at a two-sided alpha of 0.05. Next, covariates known to theoretically influence the outcomes were included and multivariate comparisons were conducted with adjusted Cox proportional hazards (PH) models [20] to examine the effects of depressive symptoms on clinical disease outcomes beyond effects of potential confounders. Covariates—age [1], race/ethnicity [21], partner status [22], chemotherapy [23], and study condition (control vs. intervention)– were manually entered into the regression model [24].

Significance of hazard ratios (HR) estimates was based on a two-sided alpha of 0.05, and confidence intervals (at 95%) were obtained for each estimate. Unadjusted KM survival curves and adjusted Cox PH models tested for differences in outcomes by the 3-group categorization of depressive symptoms (none/low, mild, moderate). Cox PH models were repeated using a continuous depressive symptom severity score as a predictor in both unadjusted and adjusted models. Finally, all analyses were repeated in the subgroup of women diagnosed with stage I-IIIb (i.e., invasive subsample), thereby excluding women with stage 0 (lobular or ductal carcinoma in-situ) breast cancer.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Among 240 participants enrolled, 231 completed the HDRS and 9 declined the interview. At enrollment, women were just over one month from surgery (M=40.74 days, SD=23.20). Women were an average of 50.16 (SD=8.97) years old, with 37.7% of an ethnic minority group. The average HDRS score was 7.52 (SD=5.46) with 136 (58.9%) scoring ≤7 (low depressive symptom group) and 95 (41.1%) > 7 (moderate/mild depressive symptom group). Depression severity ranges according to the Zimmerman et al. [17] classification were as follows: none (0-7) = 136 (58.9%); mild (8-16) = 75 (32.5%); moderate (17-23) = 20 (8.7%); severe (≥ 24) = 0 (0%).

At the 8-15 year follow-up, 28 (12.1%) of the 231 had passed away. Cause of death for 21 was specified as breast cancer-related. A total of 44 (19.0%) had experienced a breast cancer recurrence and were alive at follow-up. Participants who were alive or had not experienced a recurrence were censored in the relevant analyses. Low and moderate/mild depressive subgroups significantly differed at baseline on age (p=.014), race/ethnicity (p=.013), and partner status (p=.046). There was a slight difference in receipt of chemotherapyb between groups that did not reach statistical significance (p=.080). These factors were included as covariates in adjusted Cox PH models to control for potential confounding. Low and high depressive symptom subgroups did not differ with regard to demographic, medical (e.g., stage) or other treatment-related (e.g., extent of surgery, radiation, hormonal therapy) characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Demographic, Medical, and Treatment Variables by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale subgroup (N=231)

| Variable | n† | Total Mean (SD/%) | Low Depressive Symptoms | High Depressive Symptoms | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 231 | 50.16 (8.97) | 51.37 (9.19) | 48.43 (8.40) | .014 |

| Race/ethnicity | 230 | .013 | |||

| White non-Hispanic | 143 (62.2%) | 95 (69.9%) | 48 (51.1%) | ||

| Hispanic | 61 (26.5%) | 27 (19.9%) | 34 (36.2%) | ||

| African American | 21 (9.1%) | 10 (7.4%) | 11 (11.7%) | ||

| Asian | 5 (2.2%) | 4 (2.9%) | 1 (1.1%) | ||

| Employment | 231 | .862 | |||

| Not Employed | 57 (24.7%) | 33 (24.3%) | 24 (25.3%) | ||

| Employed | 174 (75.3%) | 103 (75.7%) | 71 (74.7%) | ||

| Education | 231 | .290 | |||

| ≤ High School | 30 (13.0%) | 15 (11.0%) | 15 (15.8%) | ||

| > High School | 201 (87.0%) | 121 (89.0%) | 80 (84.2%) | ||

| Income (thousands) | 206 | 80.56 (67.86) | 85.40 (63.24) | 73.67 (73.79) | .223 |

| Partnered status | 231 | .046 | |||

| Not partnered | 87 (37.7%) | 44 (32.4%) | 43 (45.3%) | ||

| Partnered | 144 (62.3%) | 92 (67.6%) | 52 (54.7%) | ||

| Menopausal status | 231 | .237 | |||

| Premenopausal | 106 (45.9%) | 58 (42.6%) | 48 (50.5%) | ||

| Postmenopasual | 125 (54.1%) | 78 (57.4%) | 47 (49.5%) | ||

| Stage | 230 | .304 | |||

| 0 | 39 (17.0%) | 23 (17.0%) | 16 (16.8%) | ||

| I | 80 (34.8%) | 53 (39.3%) | 27 (28.4%) | ||

| II | 88 (38.3%) | 48 (35.6%) | 40 (42.1% | ||

| III | 23 (10.0%) | 11 (8.1%) | 12 (12.6%) | ||

| Surgery to enrollment (days) | 231 | 40.74 (23.20) | 39.60 (22.42) | 42.37 (24.30) | .374 |

| Positive lymph nodes | 230 | 1.47 (3.27) | 1.63 (3.77) | 1.25 (2.39) | .390 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 119 | 1.83 (1.37) | 1.71 (1.13) | 2.00 (1.68) | .262 |

| ER status | 192 | .814 | |||

| Positive | 151 (78.6%) | 89 (78.1%) | 62 (79.5%) | ||

| Negative | 41 (21.4%) | 25 (21.9%) | 16 (20.5%) | ||

| PR status | 172 | .981 | |||

| Positive | 107 (62.2%) | 64 (62.1%) | 43 (62.3%) | ||

| Negative | 65 (37.8%) | 39 (37.9%) | 26 (37.7%) | ||

| HER2/neu | 114 | .141 | |||

| Positive | 26 (22.8%) | 13 (18.3%) | 13 (30.2%) | ||

| Negative | 88 (77.2%) | 58 (81.7%) | 30 (69.8%) | ||

| Procedure | 231 | .765 | |||

| Lumpectomy | 117 (50.6%) | 70 (51.5%) | 47 (49.5%) | ||

| Mastectomy | 114 (49.4%) | 66 (48.5%) | 48 (50.5%) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 221 | .08 | |||

| Yes | 123 (55.7%) | 66 (50.8%) | 57 (62.6%) | ||

| No | 98 (44.3%) | 64 (49.2%) | 34 (37.4%) | ||

| Radiation therapy | 217 | .981 | |||

| Yes | 130 (59.9%) | 76 (59.8%) | 54 (60.0%) | ||

| No | 87 (40.1%) | 51 (40.2%) | 36 (40.0%) | ||

| Endocrine therapy | 219 | .973 | |||

| Yes | 156 (71.2%) | 92 (71.3%) | 64 (71.1%) | ||

| No | 63 (28.8%) | 37 (28.7%) | 26 (28.9%) | ||

| Antidepressants | 231 | .170 | |||

| Yes | 24 (10.4%) | 11 (8.1%) | 13 (13.7%) | ||

| No | 207 (89.6%) | 125 (91.9%) | 82 (86.35) | ||

| Study group | 231 | .299 | |||

| CBSM | 117 (50.6%) | 65 (47.8%) | 52 (54.7%) | ||

| Control | 114 (49.45%) | 71 (52.2%) | 43 (45.3%) | ||

| Baseline HDRS | 231 | 7.52 (5.46) | 3.79 (2.01) | 12.86 (4.24) | <.001 |

Note: CBSM = Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management; ER = Estrogen Receptor; PR = Progesterone Receptor; HER2/neu = Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor; HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Sample size varies based on availability of information from medical records

Full Sample

Overall survival

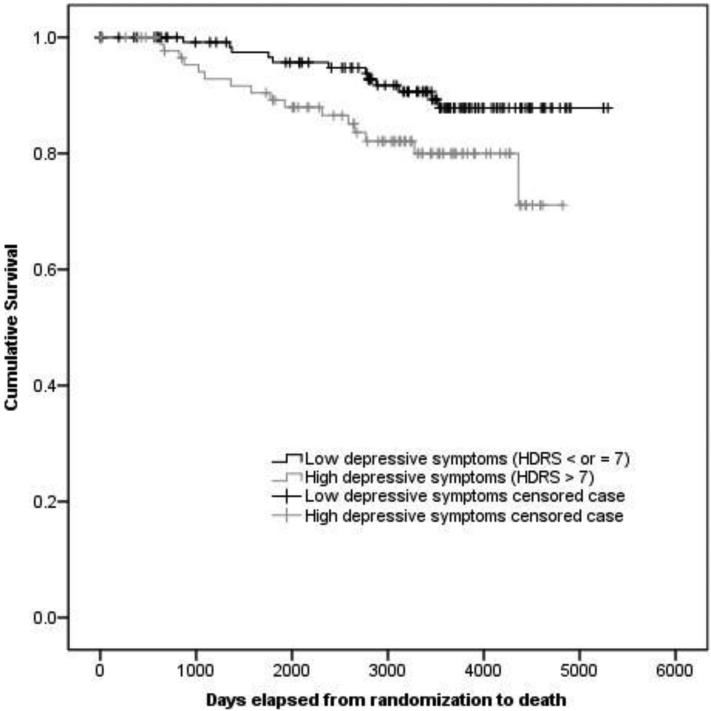

KM survival estimates showed that women in the low depressive group had longer survival (M survival=13.56 years; SE=.26) compared to the moderate/mild depressive group (M survival=11.45 years; SE=.40; Log-rank χ2(1)=4.41, p=.036; see Figure 1). Cox PH models, adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, partner status, chemotherapy, and study condition showed that the low depressive group had longer survival than the moderate/mild group (High depressive Mortality HR: 2.56, 95% CI, 1.11 to 5.91; p=.027; Table 2).

Figure 1.

Full sample: KM survival function for women classified as High (HDRS >7) vs. Low (HDRS ≤7) at study entry

Note: HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Table 2.

Full sample. Adjusted Cox proportional hazards models of depressive symptoms predicting clinical disease outcomes at 11-year follow-up (N=231)

| High (>7) vs. Low (≤ 7) Depressive Symptoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Cause Mortality | Breast Cancer Recurrence | |||

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p |

| High HDRS (vs. low) | 2.56 (1.11-5.91) | .026* | 1.45 (0.77-2.70) | .243 |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.98 (0.94-1.03) | .497 | 0.96 (0.93-1.00) | .055 |

| Race/Ethnicity | - | .124 | - | .340 |

| AA (vs. white) | 1.19 (0.34-4.17) | 1.35 (0.55-3.34) | ||

| Hispanic (vs. white) | 0.46 (0.15-1.45) | 0.53 (0.23-1.21) | ||

| Asian (vs. white) | 4.29 (0.88-20.93) | 0.73 (0.10-5.57) | ||

| Single (vs. partnered) | 1.20 (0.54-2.67) | .652 | 0.97 (0.51-1.85) | .930 |

| No chemotherapy (vs. yes) | 0.46 (0.18-1.8) | .105 | 0.45 (0.21-0.95) | .037* |

| Control (vs. intervention) | 0.92 (0.42-2.02) | .826 | 1.11 (0.60-2.05) | .748 |

| Continuous Depressive Symptoms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-Cause Mortality | Breast Cancer Recurrence | |||

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p |

| Depressive symptoms | 1.08 (1.02-1.16) | .016* | 1.04 (0.99-1.10) | .164 |

| Age at diagnosis | 0.98 (0.94-1.03) | .440 | 0.96 (0.93-1.00) | .047* |

| Race/Ethnicity | - | .146 | - | .330 |

| AA (vs. white) | 1.15 (0.33-4.06) | 1.29 (0.52-3.21) | ||

| Hispanic (vs. white) | 0.44 (0.14-1.38) | 0.52 (0.23-1.18) | ||

| Asian (vs. white) | 3.56 (0.76-16.65) | 0.68 (0.09-5.17) | ||

| Single (vs. partnered) | 1.22 (0.55-2.71) | .621 | 0.98 (0.51-1.85) | .937 |

| No chemotherapy (vs. yes) | 0.46 (0.18-1.19) | .110 | 0.45 (0.21-0.96) | .039* |

| Control (vs. intervention) | 0.90 (0.41-1.98) | .790 | 1.08 (0.58-2.01) | .802 |

Note: HR= Hazard Ratio; CI = Confidence Interval; HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, AA = African American

p<.05.

Depressive symptom severity as three groups (none, mild, moderate) was also associated with survival (Log-rank χ2(2)=7.96, p=.019), such that women with moderate depressive symptoms had the shortest survival (M survival=10.09 years; SE=.25), followed by the mild symptom group (M survival=11.83 years; SE=.41), then women with no depressive symptoms (M survival=13.56 years; SE=.26). Covariate-adjusted Cox PH models (Figure 2) revealed that women with no depressive symptoms had significantly longer survival than those with moderate depressive symptoms (Moderate depressive mortality HR: 4.48, 95% CI, 1.48 to 13.56, p=.008). No significant difference was found between mild and moderate depressive symptom subgroups after inclusion of covariates.

Figure 2.

Full Sample: Cox PH model for overall survival (using 0.6 – 1.0 scaling) for women classified as no/low (0-7), mild (8-16), or moderate (17-23) depressive symptoms at study entry

Note: HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

When examining severity of depressive symptoms on a continuous scale, the unadjusted Cox PH model showed greater HDRS scores associated with shorter survival (HR, 1.08, 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.14; p=.015). Adjusting for covariates yielded similar results; greater depressive symptoms were associated with shorter survival (HR, 1.08, 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.16; p=.016; Table 2).

Disease-free interval

No significant differences were found in disease-free interval for moderate/mild versus low HDRS depressive symptoms, continuous depressive symptoms, or the 3-group categorization of depressive symptoms in KM survival curves or adjusted Cox PH models (Table 2).

Invasive Tumor Subsample

Overall survival

Among cases with invasive but non-metastatic tumors (stage I-IIIb, n=191), all-cause findings were consistent with those for the overall sample. KM survival estimates for moderate/mild (n=79) versus low (n=112) depressive symptom groups showed the low depressive group (M survival=13.45 years; SE=.30) had longer survival than the moderate/mild depressive group (M survival=11.15 years; SE=.46; Log-rank χ2(1)=4.92, p=.027; see Supplemental Fig. 2). Adjusted Cox PH models in this subsample also showed that the low depressive group had longer survival than the moderate/mild group, (High depressive mortality HR 2.59, 95% CI, 1.12 to 5.97; p=.026, Supplemental Table 3).

Depressive symptom severity as three groups was also associated with survival in this subsample (Log-rank χ2(2)=8.81, p=.012). Women with moderate depressive symptoms had the shortest survival (M survival=9.63 years; SE=1.05), followed by the mild symptom group (M survival=11.61 years; SE=.47), then the no depressive symptom group (M survival=13.45 years; SE=.30). Adjusted Cox PH models revealed that women with no depressive symptoms had significantly longer survival than those with moderate symptoms (Moderate HR: 4.60, 95% CI, 1.47 to 14.37, p=.009). No significant difference was found between mild and moderate groups.

Considering severity of depressive symptoms on a continuum, unadjusted Cox PH model showed greater HDRS scores were associated with shorter survival (HR, 1.08, 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.14; p=.015). Adjusting for covariates yielded similar results, with greater depressive symptoms associated with shorter survival (HR, 1.08, 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.16; p=.018, Supplemental Table 3).

Disease-free interval

No significant differences were found in disease-free interval for moderate/mild versus low HDRS depressive symptoms, continuous depressive symptoms, or the 3-group categorization of depressive symptoms in KM survival curves or adjusted Cox PH models invasive tumor subsample (supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

This study found greater postsurgical depressive symptoms in 231 patients with non-metastatic breast cancer were associated with shorter survival (all-cause) at 8-15 year follow-up. Women who report low depressive symptoms before they begin adjuvant treatment have a survival advantage beyond treatment and demographic factors that differed between them and more depressive women. Findings were robust whether depressive symptoms were tested on a severity continuum, as low versus mild/moderate depressive symptoms subgroups, or as no/low versus mild versus moderate depressive symptom subgroups using accepted clinical cut-offs [17,18]. Depressive symptoms were not associated with breast cancer recurrence. Similar results were obtained when examining women with invasive tumors only (stage I-IIIb).

Results are consistent with studies showing that depressive symptoms predict mortality in breast cancer, as demonstrated in samples of non-metastatic [10,11] and metastatic breast cancer [9], and in a study combining all breast cancer stages [12]. Findings are in line with meta- analyses showing that higher levels of depressive symptoms predict elevated mortality in cancer patients [6,7] and in breast cancer patients specifically [4]. As did previous research [6,13], the current study failed to find an association between depressive symptoms and breast cancer recurrence. It is possible that other behavioral and psychosocial factors not measured in this study (e.g., accessibility to or compliance with follow-up care, patient-physician communications) could influence detection of disease recurrence [25].

The average follow-up for studies that show depressive symptoms to predict mortality is 5 years [6]. This study extends these findings by showing a similar association in a longer follow-up of 8-15 years (11-year median). This study is novel in that we observed these associations in women who did not initially have MDD or major psychopathology. This suggests that the findings are generalizable to the majority of women who experience non-psychiatric levels of distress during primary treatment. Over 37% of the sample was of a racial/ethnic minority thereby increasing generalizability of the findings beyond non-Hispanic White women.

Proposed mechanisms by which depressive symptoms predict poorer survival in breast cancer include physiological (i.e., immune and neuroendocrine function) [2,14,26] and behavioral pathways (i.e., treatment non-adherence, maladaptive coping) [25,27,28]. Cortisol dysregulation, frequently observed in depressed patients [29], predicts shorter overall survival in breast cancer [26], and is a potential mediating pathway [14], In breast cancer patients, inflammatory cytokines are associated with degree of depressive symptoms [30], and evidence suggests that elevated inflammation may promote pathophysiologic processes [3]. Alleviating depressive symptoms during primary treatment may help normalize neuroendocrine and inflammatory processes [31], which could provide health benefits.

Breast cancer patients with depressive symptoms may be less likely to adhere to treatments, medical follow-ups, screening, and recommendations for health maintenance [25,32], that may influence survival outcomes. Depressed patients often suffer from a lack of social support [27], have more difficulty handling complex healthcare regimens [7], and may employ maladaptive coping strategies [28], all of which may increase risk for mortality. Given that lower socioeconomic status is a risk factor for depression, it is possible that more depressed patients in our sample had less access to healthcare or resources, though we controlled for education and employment status. Future research should aim to assess mediators of the relationship between depressive symptoms and mortality observed here and elsewhere [7].

Importantly, depressive symptoms in the current study were reported in the days following diagnosis and treatment initiation, which are shown to be stress-inducing [33] and lead to increased risk for a depressive episode. Psychiatric symptoms increase risk for disease-related morbidity and mortality [34]; however, the psychological needs of these patients are largely unmet. Given the amount of patient-provider interaction around the time of diagnosis and treatment initiation, healthcare providers could capitalize on this window of opportunity to provide skills to buffer the effects of stress and downstream potential for a depressive episode.

A limitation of the study is that all participants were included regardless of distress level and depression levels were truncated, in fact, by the exclusion of those diagnosed with MDD. Hence the sample may be representative of newly diagnosed patients with a range of non-severe depressive symptoms, but may not be generalizable to those with clinical levels of depressive symptoms. However, the exclusion of patients with current MDD or prior psychiatric hospitalizations, and the low prevalence of patients taking antidepressants at study entry, suggests the current sample's depressive symptoms reflect their coping with ongoing stress of cancer diagnosis and treatment, rather than pre-morbid mental health issues. To assess whether severe depressive symptoms are related to disease outcomes, studies should consider inclusion of participants with severe levels of depressive symptoms and MDD [6]. Although our study was limited to the use of the HDRS, self-reported measures of depressive symptoms (Affect Balance Scale – depressive subscale and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale) were positively associated with the HDRS in our sample at baseline (r=.461, p <.001), and at 5-year follow-up (r=.313, p <.001), respectively. Generalizability is also limited by the academic study setting, geographical location of the study, and the fact that women were participating in an intervention trial. Although we controlled for major demographic and medical confounding variables, we did not have complete data on other factors (e.g., body mass index, medications, comorbidity index); therefore, these were not included in the model to maximize sample size, and to avoid overfitting the models [24]. Unfortunately, we do not have information on the mental or physical health status of women who did not participate in the study, therefore we cannot determine whether the current sample was more or less depressed than those choosing not to participate in a psychosocial study. Future research should examine longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms and the effect on survival [9]. Finally, studies should examine whether effective psychotherapeutic or pharmacological treatment of depressive symptoms during breast cancer treatment can decrease mortality [7].

Conclusions

In summary, women with non-metastatic breast cancer who report mild to moderate depressive symptoms in the weeks after surgery have approximately 2.5 times greater risk of death 8-15 years later than women who report little or no depressive symptoms post-surgery. Depressive symptoms were not associated with breast cancer recurrence. Although the association between depression and all-cause mortality is well-established in the general population, our findings that depressive symptoms were associated with mortality in women with breast cancer are significant given that they are at higher risk for early mortality than the general population. Findings warrant a randomized trial to truly determine whether subclinical depressive symptoms may affect long-term clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Janny Rodriguez for coordinating this study, and Lynne Hudgins for managing fiscal aspects of the project. We acknowledge the contribution of surgical oncologists at Jackson Memorial Hospital, Sylvester Cancer Center, and private clinical practices in Dade and Broward counties, for help in recruiting participants. Finally we thank the staff, psychology graduate students, and post-doctoral fellows who participated in screening, assessment, and intervention activities.

Funding: This project was funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Contract No. HHSN261200800001E and NCI grant R01-CA-064710. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views of policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Contract No. HHSN261200800001E provided statistical support and interpretation of data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

KM curves were plotted for models with categorical predictors not adjusted for covariates. Cox PH models were used for adjusted models and those with continuous predictors.

The influence of depression on mortality is shown to be independent of disease stage. However, stage of disease was highly correlated with receipt of chemotherapy, [r = 0.63, p < .001] therefore analyses indirectly accounted for disease stage. 7. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 2010; 40: 1797-1810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285

Conflict of Interest:

Dr. Antoni reports publication royalties from a book and training materials on cognitive-behavioral stress management. Dr. Glück reports employment at Celgene Corporation. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2016. 66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antoni MH, Wimberly SR, Lechner SC, et al. Reduction of cancer-specific thought intrusions and anxiety symptoms with a stress management intervention among women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1791–1797. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1791. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Antoni MH. Host factors and cancer progression: biobehavioral signaling pathways and interventions. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28:4094–4099. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nature Clinical Practice: Oncology. 2008;5:466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen L, Cole SW, Sood AK, et al. Depressive symptoms and cortisol rhythmicity predict survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma: role of inflammatory signaling. PloS One. 2012;7:e42324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Cancer. 2009;115:5349–5361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24561. doi: 101002/cncr.24561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1797–1810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kissane D, Maj M, Sartorius N. Depression and Cancer. 1 Ed. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Hoboken, NJ: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, et al. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:413–420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. doi: 101200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hjerl K, Andersen EW, Keiding N, et al. Depression as a prognostic factor for breast cancer mortality. Psychosomatics. 2003;44:24–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.1.24. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson M, Homewood J, Haviland J, Bliss JM. Influence of psychological response on breast cancer survival: 10-year follow-up of a population-based cohort. European Journal of Cancer. 2005;41:1710–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.01.012. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanani R, Davies EA, Hanchett N, Jack RH. The association of mood disorders with breast cancer survival: an investigation of linked cancer registration and hospital admission data for South East England. Psycho-Oncology. 2016;25:19–27. doi: 10.1002/pon.4037. doi: 101002/pon.4037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips KA, Osborne RH, Giles GG, et al. Psychosocial factors and survival of young women with breast cancer: a population-based prospective cohort study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:4666–4671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J. Depression and cancer: mechanisms and disease progression. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:269–282. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00566-3. doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncology. 2011;12:160–174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. doi, PMC495331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmerman M, Posternak MA, Chelminski I. Implications of using different cut-offs on symptom severity scales to define remission from depression. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;19:215–220. doi: 10.1097/01.yic.0000130232.57629.46. doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K. Severity classification on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;150:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.028. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rich JT, Neely JG, Paniello RC, et al. A practical guide to understanding Kaplan-Meier curves. Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery. 2010;143:331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.007. doi: 101016/j.otohns.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox D. Regression models and life-tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1972;34:187–220. doi. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Keefe EB, Meltzer JP, Bethea TN. Health disparities and cancer: racial disparities in cancer mortality in the United States, 2000-2010. Front Public Health. 2015;3:51. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00051. doi: 103389/fpubh.2015.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:3869–3876. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6489. doi: 101200/JCO.2013.49.6489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.EBCTCG Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Babyak MA. What you see may not be what you get: a brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:411–421. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127692.23278.a9. doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sephton SE, Sapolsky RM, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Diurnal cortisol rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:994–1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Epstein R, Street R. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. (Vol. 07-6225) National Cancer Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faller H, Störk S, Gelbrich G, et al. Depressive symptoms in heart failure: Independent prognostic factor or marker of functional status? Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2015;78:569–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.02.015. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sephton SE, Dhabhar FS, Keuroghlian AS, et al. Depression, cortisol, and suppressed cell-mediated immunity in metastatic breast cancer. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23:1148–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.07.007. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouchard LC, Antoni MH, Blomberg BB, et al. Postsurgical Depressive Symptoms and Proinflammatory Cytokine Elevations in Women Undergoing Primary Treatment for Breast Cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2016;78:26–37. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000261. doi: 101097/PSY.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antoni MH, Lutgendorf SK, Blomberg B, et al. Cognitive-behavioral stress management reverses anxiety-related leukocyte transcriptional dynamics. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.007. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raison CL, Miller AH. Depression in cancer: new developments regarding diagnosis and treatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:283–294. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00413-x. doi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blomberg BB, Alvarez JP, Diaz A, et al. Psychosocial adaptation and cellular immunity in breast cancer patients in the weeks after surgery: An exploratory study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.016. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, et al. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:1605–1619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4611. doi: 101200/JCO.2013.52.4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.