Abstract

Aims

To describe patterns of cannabis use, the degree of overlap between medicinal and recreational users, and their differential use patterns, modes of consumption and sources of cannabis.

Design

An ongoing probability-based internet panel maintained by the market research firm GfK Group.

Setting

Households in Colorado, Washington, Oregon and New Mexico, USA.

Participants

2009 individuals from Washington (n=787), Oregon (n=506), Colorado (n=503), and New Mexico (N=213). Post stratification sampling weights were provided so that estimates could be made representative of the household population in each of these states. Respondents were between 18 and 91 years old with a mean age of 53.

Methods

We compare patterns of cannabis consumption for medicinal and recreational users as well as simultaneous use of alcohol and cannabis. We also examine the extent to which patterns of use differ across states that chose to legalize (Washington and Colorado) and those that did not (New Mexico and Oregon).

Findings

Rates of lifetime medical cannabis use are similar in Colorado and Washington (8·8% and 8·2%) but lower in Oregon and New Mexico (6.5% and 1%). Recreational use is considerably higher than medical use across all states (41%) but highest in Oregon and Washington. About 86% of people who report ever using cannabis for medicinal purposes also use it recreationally. Medical users are more likely to vaporize and consume edibles, and report a higher amount (in grams) consumed, and spend more money per month than recreational users. Individuals who use cannabis do not commonly use it with alcohol, irrespective of whether they are consuming cannabis recreationally or medically. Fewer than 1 in 5 recreational users report simultaneous use of alcohol and cannabis most or all of the time and less than 3% of medicinal users report frequent simultaneous use of alcohol and cannabis.

Conclusions

In the USA, the degree of overlap between medicinal and recreational cannabis users is 86%. Medicinal and recreational cannabis users favour different modes and amounts of consumption. Only a small proportion (12%) of cannabis users usually consume cannabis and alcohol simultaneously, while concurrent use is common among recreational users.

Keywords: medical use, cannabis legalization, form of cannabis consumed, personal use

I. Introduction

As a result of recent voter-approved initiatives, the sale of recreational cannabis commenced on January 1, 2014 in Colorado and in July 2014 in Washington. Voters in Alaska, Oregon and the District of Columbia approved similar initiatives in November 2014. Several other states, including California, are expected to legalize recreational cannabis use within the next few years. These legalization initiatives follow on the heels of almost two decades worth of state medical cannabis initiatives. As of May 2015, 24 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws allowing the use of cannabis for medical purposes and seven more states have legislation pending on this issue.

Although many states have passed medical cannabis laws, the recent recreational cannabis initiatives mark a dramatic shift in US cannabis policy from the complete outlaw of recreational sales, if not use, to the explicit sanctioning of it. Of particular interest is how these initiatives will affect future recreational and medical cannabis use.

While many argue that medical cannabis laws amount to de facto legalization,1-3 we have a remarkably limited understanding of consumption patterns among “medical” vs. recreational users in the many states that already allow medical use. Most work focuses on the demographic characteristics of self-identified medicinal users,4-6 stressing differences vis-à-vis recreational users, the conditions for which medicinal users seek recommendations, or the conditions for which they are currently using it medicinally.7-9 A few studies show that a large share of medicinal users also use cannabis recreationally9,10 but most studies have focused on special populations, such as people with HIV/AIDS11-,13 non-cancer pain,14 and multiple sclerosis15,16 and may not be representative of the general population.17 The one study we were able to identify that examined medicinal and recreational use in the general population used a household sample from a single city.4 By looking at households across four states, this work can provide a broader understanding of medical and recreational cannabis use.18 In addition, this paper fills a void in the literature by examining the degree of overlap between medicinal and recreational users, as well as their differential use patterns, modes of consumption, and sources for cannabis. Understanding whether and how patterns of use among self-reported medical users differs from that of recreational users, and whether medical and recreational users access cannabis through the same or different sources should help us better understand the extent to which the legalization of cannabis for recreational purposes, and in particular the opening of (non-medical) retail stores, will further change access and use.

We make use of a new four-state household representative survey that we fielded in October 2013 in Colorado, Washington, Oregon and New Mexico, states that all have established medical cannabis laws. Qualifying medical conditions vary somewhat across the four state medical cannabis laws but all four cover cancer, glaucoma, HIV/AIDS, seizure disorders, cachexia, muscle spasms, severe pain and severe nausea.19-22 Although Washington and Colorado had passed legalization initiatives by October 2013, neither state allowed retail stores for recreational use at that time. As a result, during our survey period only medicinal users had a legitimate source of supply beyond home cultivation. This baseline survey therefore enables us to describe patterns of use and access to cannabis among self-proclaimed medicinal and recreational users before retail stores for recreational cannabis were open in any state. Of particular relevance to the ongoing debate about legalization, we examine self-reported simultaneous use of alcohol and cannabis–defined as use at the same time23, thereby providing unique insights into the nature of the relationship between alcohol and cannabis across different types of users. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to describe detailed medicinal and recreational cannabis use patterns in a representative household survey.

II. Methods. The RAND Marijuana Use in West Coast States Survey

In October 2013, the RAND Corporation, with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, fielded The RAND Marijuana Use West Coast States survey to the KnowledgePanel®, an ongoing probability-based internet panel maintained by the market research firm GfK Group. KnowledgePanel® members are recruited using a published sample frame of residential addresses that covers approximately 97% of U.S. households. Individuals are invited by telephone or mail to participate in the panel, and those that agree are given unique log-in information for accessing surveys online. People who do not have internet access are provided at no cost a laptop with ISP connection so they can participate. Emails are sent throughout the month inviting participants to log-in and partake in monthly surveys that are administered for a variety of research purposes. At present, the full KnowledgePanel® consists of about 50,000 adult members (ages 18 and older) and includes persons living in cell phone only households. We surveyed only panel members living in Colorado, Washington, Oregon and New Mexico.

Our survey targeted English-speaking adults (age 18 years and older), in the four states and consisted of about 1500 regular KnowledgePanel® participants and about 600 new “refresher” participants, for a total of 2,100 targeted interviews. The survey was designed to take 3 minutes on average and consisted of a series of questions regarding lifetime, past year and past month use of cannabis for medicinal and recreational purposes, simultaneous use of cannabis and alcohol, as well as a series of questions regarding where and how cannabis is used and at what price it is obtained. The study was purposefully designed so that respondents would clearly differentiate use for medicinal purposes from use for recreational purposes. For example, we began by asking each respondent “Have you ever used marijuana for medicinal purposes?”1 If the respondent replied yes, we then asked the age at initiation for medicinal purposes, the number of days they used in the past 12 months for medicinal purposes, and the number of times in the past 30 days in which they used cannabis for medicinal purposes. We also inquired about the source of their medical recommendation and their method of medicinal use (smoking, vaporizing, in food, etc). Thus, we can construct lifetime, annual and thirty-day prevalence measures for medicinal use specifically. We did not define medicinal for respondents, leaving them to determine if their own use was medicinal or not. We did, however, ask about reported source of a medical recommendation.

We separately inquired about whether respondents “ever used marijuana for recreational (non-medical) purposes?” and asked the same series of questions about initiation, frequency, and method of recreational use. Finally, respondents were surveyed about how they consumed marijuana, where and whether they consumed marijuana with alcohol. When inquiring about alcohol consumption, we asked individuals who reported use of alcohol in the past month, “When you drank alcohol in the past month, how often did you also use marijuana while drinking.”

We obtained completed surveys from a total of 2009 individuals from Washington (n=787), Oregon (n=506), Colorado (n=503), and New Mexico (N=213) from a total of 2,722 fielded surveys (74% response rate). Post stratification sampling weights were provided so that estimates could be made representative of the household population in each of these states. All analysis was conducting using Stata 12. Respondents were between 18 and 91 years old with a mean age of 53.

Since 15 respondents refused to answer questions pertaining to ever using cannabis (recreationally or medicinally), our final analytic sample consists of 1994 participants (71% of initial fielded group). Those who refused to answer the cannabis questions were primarily white, married, employed as paid employees or retired, owned a one-family house, were household heads, and had some college education but not a bachelor's degree. This group was not statistically different from respondents along any of these key characteristics. The only distinguishing characteristics of non-respondents as compared to those who responded about their cannabis use was that they were more likely to be female (13 of 15) and less likely to be the head of household.

III. Results

III.A. Descriptive Statistics from the Pooled Four States

In Appendix Table 1 (online supporting information) we provide descriptive statistics for our sample, broken out by residency in Colorado, Washington or the (combined) non-legalizing states of Oregon and New Mexico. We combined the non-legalizing state data because of the small sample size in New Mexico (N=210). We break out the Colorado and Washington data separately to see if these two states were unique in 2013, before retail recreational cannabis sales had begun. As in many household surveys, the vast majority of our survey respondents were female (62% female versus 38% male). Given the racial composition of the states we studied, they were also overwhelmingly white (84% white, 8% Hispanic, 2.1% black, 2.2% other, 3.7% two or more races). Over 60% of respondents were older than 40 years of age and only about 15% were younger than 30. Thus, the sample, although representative of the states of interest, may be limited in providing very detailed views of substance abuse behavior among young adults specifically.

Table 1. Patterns of Medicinal and Recreational Use & How Cannabis is Obtained.

| Medical Cannabis | Recreational Cannabisb | P-value of difference (Ho: means are equal) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever used in lifetime | 0.07 | 0.41 | P<.001 |

| Age of 1st Use | 32.07 | 18.64 | P<.001 |

| Past Year Prevalence | 0.06 | 0.12 | P<.001 |

| Days of use in Past Year | 10.93 | 13.17 | 0.267 |

| Past Month Prevalence | 0.05 | 0.09 | P<.001 |

| Days of use in Past Month | 4.42 | 3.5 | 0.61 |

| No MD Recommendation | 0.529 | ||

| Method of use the last time used:c | |||

| Smoking | 0.78 | 0.93 | 0.003 |

| Vaporizing | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Eating | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.006 |

| Drinking | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.34 |

| Other | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.11 |

| How did you obtain MJ last time? | |||

| Grew it | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| Got it for Free | 0.28 | 0.69 | 0.02 |

| Paid a friend | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

| Got it from dispensary | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Obtained from a dealer | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.45 |

| Other | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.87 |

| Where did you consume it? | |||

| At a dispensary/coop | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| In a residence | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.72 |

| At a public park/outside venue | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.21 |

| On the street | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.37 |

| In my car | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| In a bar/restaurant | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.32 |

| Other | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.52 |

| How much spent per month on MJ? | $48.23 | $12.41 | 0.08 |

| Usually/always use alcohol at same time? | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.31 |

Those reporting medical and recreational use can overlap.

These do not add up to 1 because responders could select two or more ways to consume cannabis

In Table 1 we examine patterns of medicinal and recreational cannabis use drawing on the pooled sample from all four states. About 7% of individuals report using medical cannabis in their lifetimes. Almost 53% of these individuals stated that they did not have a physician's recommendation for medical use, suggesting a divergence between a state's legal definition of medical use and a person's self-reported intent. The average age of first medical cannabis use was 32 years old. In contrast, almost 41% of individuals reported ever using cannabis for recreational purposes, with a substantially younger average age of first use (18.6). The older average age at first medical cannabis use may reflect in part the fact that: (1) medical cannabis is a relatively new phenomenon (less than 2 decades old in this sample) while the average age of our respondents is over 40, and (2) medical use is only legal in these states at age 18, whereas recreational use, at the time of the survey, was illegal for all age groups. If we limit the sample to those under age 40, the difference in the age of first medical and first recreational cannabis use remains but was far less stark – 21 versus 17 years old, respectively (not shown).

Past year prevalence rates were half as high for medical (6%) than for recreational cannabis (12%); past month prevalence rates were a bit closer (5% versus 9%). Individuals who reported medicinal use consumed cannabis in a different manner than those who report recreational use. Of those who used medical cannabis, about 78% smoked cannabis, 32% consumed edibles, and 18% vaporized it. Nearly all recreational cannabis users smoked (93%) while only 3% vaporized and 8% consumed edibles. Whereas 68% of recreational cannabis users reported obtaining the drug for free the last time they used, only 28% of medical cannabis users did so. This is reflected in the average monthly dollar amount spent by users. Recreational users reported spending a little over twelve dollars per month on cannabis, while medical cannabis users reported spending about forty eight dollars per month. A majority of medical and recreational users reported consuming cannabis in a residence (80% and 82%, respectively). Finally, simultaneous use of alcohol and cannabis, defined as ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’ using alcohol and cannabis together, was similar (about 12-13%) for both recreational and medicinal users.

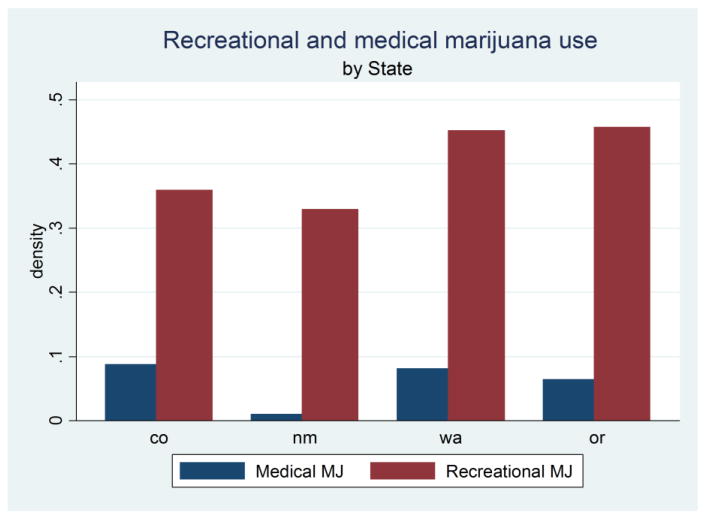

We also consider differences in the patterns of use across our four states prior to the opening of legal stores for recreational sales in any of the four states. As shown in Figure 1, rates of lifetime medical cannabis use were similar in Colorado and Washington, 8.8% and 8.2%, respectively. In contrast, only 6.5% of respondents in Oregon and 1% of respondents in New Mexico ever used medical cannabis. Recreational use was quite similar in the two neighboring states of Washington and Oregon, with 45% of respondents reporting ever using recreationally. The corresponding rates in Colorado and New Mexico are 36% and 32% respectively.

Figure 1. Recreational and Medicinal use of Cannabis in the Past Month by State.

III.B. Findings of Concurrent Medical and Recreational Use

Table 2 shows the breakdown of lifetime (Panel A) and 30-day (Panel B) cannabis use by categories so that we can better understand the degree of overlap in medical and recreational use. Overall, 42% of respondents ever used cannabis, with the vast majority of these lifetime users reporting recreational use only (35.14% of the household population, but 83% of those who reported ever using cannabis). Less than 1% of the household population reported only using cannabis for medicinal purposes in their lifetime (2.3% of all people who reported lifetime use), but in total 7.17% of the entire household population (16.9% of lifetime users) had used cannabis medicinally at some point in their life. Medicinal users represent a relatively small share (less than 1/5th) of lifetime users. Interestingly, most individuals who ever used medically also reported recreational use (86% ). When we restrict the sample to medical users who reported having a physician's recommendation, the share who also used recreationally is reduced but the overlap remains substantial: over 75% of medical users with a recommendation reported any lifetime recreational use (not shown).

Table 2.

Breakdown of Medical and Recreational Cannabis Use

| Any Cannabis Use | Recreational Cannabis Use only | Medical Cannabis Use only | Recreational and Medical MJ Use | Any Recreational Cannabis Use | Any Medical Cannabis Use | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Lifetime Useb (% of people who reported lifetime use) N=1994 | 42.3% (100%) | 35.1% (83%) | 0.97% (2.3%) | 6.2% (14.7%) | 41.3% (97.7%) | 7.1% (16.9%) |

| Panel B: 30-Day Total use prevalence c (% of people who reported lifetime use) N=1993 | 8.8% (100%) | 4.4% (50.1%) | 2.18% (24.6) | 2.23% (25.2%) | 6.67% (74.4%) | 4.41% (49.8%) |

Percentages may not sum to group totals due to rounding

Percentages may not sum to group totals due to rounding

Medicinal cannabis users represented a larger share of those reporting cannabis use in the past month, a common metric for “regular” use. One half (49.8%) of all past month users reported medicinal cannabis use in the past thirty days. However, only half of past month medicinal users (or about 25% of past month users overall) used cannabis for medicinal purposes alone. The other half used cannabis recreationally as well. Thus, reporting use for both recreational and medicinal purposes is much higher among past month than lifetime users (25.2% versus 14.7%).

III. C. Differences in Modes of Consumption between Recreational and Medical Users

Table 3 shows differences in the patterns and modes of consumption among those who used in the past 30 days. We separated recreational consumption among those who use for both medical and recreational purposes and those who use recreationally only (Columns 1-2) and compared differences in the patterns and modes of medicinal consumption among then those who use both medically and recreationally with those who reported only using for medicinal purposes (Columns 4-5). It is interesting to note that 60% of the sample who reported any recreational use, only use cannabis recreationally (n= 67), while just over half of the sample who reported medicinal use report only using medically (46 out of 90).

Table 3. Patterns of Recreational Cannabis Use & How Cannabis is Obtained for recreational only, medical only, and medicinal and recreational users.

| Recreational Cannabis Users Responding about Recreational Use | Medical Cannabis Users Responding about Medicinal Use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical & Recreational MJ (n=44) | Recreational MJ Only (n=67) | P-value of difference (Ho: means are equal) | Medical & Recreational MJ (n=44) | Medical MJ Only(n=46) | P-value of difference (Ho: means are equal) | |

| Near daily use in past month | 70.9% | 21.8% | P<.001 | 44% | 48% | 0.83 |

| Amount last consumed (in grams per day) | 1.1 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 1.2 | 0.84 | 0.43 |

| How much spent per month on MJ? | $50.5 | $24.8 | 0.03 | $52.4 | $57.6 | 0.72 |

| Method of use the last time used:b | ||||||

| Smoking | 92.1% | 95.6% | 0.57 | 87.1% | 82.6% | 0.66 |

| Vaporizing | 10.7% | 1.4% | 0.12 | 36.3% | 16.8% | 0.24 |

| Eating | 1.1% | 12.7% | 0.09 | 32.6% | 24.4% | 0.64 |

| Drinking | 1.1% | 0.0% | 0.33 | 1.1% | 0% | 0.33 |

| How did you obtain MJ last time? | ||||||

| Grew it | 17.5% | 3.2% | 0.19 | 7.2% | 5.1% | 0.71 |

| Got it for Free | 25.1% | 57.8% | 0.03 | 30.7% | 12.6% | 0.23 |

| Paid a friend | 7.3% | 28.7% | 0.02 | 14.9% | 15.5% | 0.95 |

| Got it from dispensary | 6.1% | 2.1% | 0.35 | 6.7% | 31.8% | 0.02 |

| Obtained from a dealer | 23.9% | 4.3% | 0.07 | 20.3% | 23.3% | 0.85 |

| Other | 20.2% | 3.9% | 0.33 | 20.2% | 11.1% | 0.60 |

| Usually/always use alcohol at same time? | 2.9% | 17.4% | 0.08 | 1.1% | 0% | 0.33 |

These do not add up to 1 because responders could select two or more ways to consume cannabis

The first row of Table 3 shows the proportion of users who reported using on 20 or more days in the past month (which we label “near daily”). Column 1 now shows that out of all those who reported using cannabis for recreational purposes, the proportion who used for both medicinal and recreational purposes are far more likely to report using cannabis recreationally on a near daily basis (71%) than those who report only using for recreational purposes (22%). They also consume more on average each day than recreational only users (1.1. gram per day versus 0.35 grams), and spend more per month ($50.50 versus $24.80). In this way, the individuals who consumed for both recreational and medicinal purposes looked much more like those who used cannabis for medicinal purposes only.

Nearly half (48%) of individuals who reported past month use of cannabis for medicinal purposes only reported using cannabis for medicinal purposes near daily, while 44% of those who report using cannabis both recreationally and medicinally also reported using cannabis daily for medicinal purposes. While medical cannabis is commonly smoked, it is far more likely to be consumed in other ways, including vaporizing and eating. In contrast, recreational cannabis is almost always smoked (over 95% of the time).

The source of the cannabis differed according to intended use and type of user. Individuals who used only for medicinal purposes were far more likely to obtain cannabis from a dispensary, and far less likely to get it for free than recreational only users. Individuals who reported only using recreationally were far more likely to report getting it for free or paying a friend to get it for them, than individuals who reported using cannabis both recreationally and medicinally.

Finally, the last row of Table 3 reports the proportion of each group using alcohol “usually” or “always” when they consumed cannabis recreationally (Column 1-2) or medicinally (column 4-5). Individuals who used cannabis only for recreational purposes were much more likely to report using it usually or always with alcohol (17.4%) than those who used only medically. Individuals who used cannabis for both purposes did not commonly use it regularly with alcohol, irrespective of whether they consumed it recreationally or medically.

IV. Discussion

Our review of existing literature showed that previous studies provided a remarkably limited understanding of consumption patterns among “medical” vs. recreational users in the many states that allow medical use. While a few studies show that a large share of medicinal users also use cannabis recreationally, these focused on special populations that may not be representative of the general population.

This paper describes initial baseline survey data on recreational and medicinal cannabis use in four Western states (Colorado, New Mexico, Oregon and Washington) all of which had previously adopted and implemented medicinal cannabis laws and two of which at the time of our baseline interview allowed for legal, recreational use. To our knowledge, this paper fills a void in the literature by examining the degree of overlap between medicinal and recreational users, as well as their differential use patterns, modes of consumption, and sources for cannabis in a representative household population. By looking at households and not special populations, this survey adds value to the existing research because, in the absence of general population data, a household survey like this one will help researchers and policymakers understand the patterns of medicinal and recreational cannabis use prior to changes in legislation and regulation. We identified medical and recreational users in a representative household survey to determine how patterns of use among self-reported medical users differed from that of recreational users. We also considered whether medical and recreational users represent different populations, by evaluating, whether they access cannabis through the same or different sources. This information helps us better understand the extent to which the legalization of cannabis for recreational purposes generates new points of access or just alternative ones, particularly the opening of (non-medical) retail stores.

Our study has some important limitations. In particular, it drew on a household population that was predominantly female, had a very small proportion of young users (age < 21) and there were relatively few self-identified medical cannabis users in New Mexico. The fact that the people interviewed were predominantly female is particularly worrisome given that medicinal users identified in previous studies were predominantly male. Despite these limitations, many of our findings are consistent with those in the literature. For example, we found that while 7% of our four state combined sample reports lifetime use of cannabis for medicinal purpose, the share of the household population reporting lifetime medicinal use of cannabis was only 4.7% when we limited the households to those in NM and OR, our two control states. This lifetime prevalence rate was similar to the 5% lifetime medical cannabis use rate for California reported in a recent study using the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey.6 The higher lifetime prevalence rate in our sample was driven by Colorado and Washington, the two states that recently legalized cannabis for recreational purposes (see Appendix Table 1 supporting information online). We also found, consistent with some prior work,11 that a large majority of self-identified medical users (86% of those who self-identified as medicinal users, 76% of those who self-identified as medical users and reported having a physician recommendation) also reported cannabis use recreationally. Thus, while our sample underrepresented two important populations (males and young users), the weighted results describing general medical use patterns within the household population were broadly consistent with previous studies.

We also found that individuals who repored using cannabis for medicinal purposes were much more likely to vaporize it or consume it in food than individuals who reported using for recreational purposes (who almost exclusively smoked it). Smoking nonetheless remained the predominant method of use for both types of users. It was not clear whether these patterns of consumption reflected real differences in preferences or the fact that patients who have access to dispensaries are exposed to a broader range of products than consumers who do not have access to retail stores. Indeed, an interesting area for consideration was whether these patterns of consumption converge as retail recreational cannabis stores include the same range of cannabis products as medical stores have in Colorado and Washington.

The baseline study findings suggest that only a small share (12%) of cannabis users usually consumed cannabis simultaneously with alcohol, an issue of particular concern for those opposed to legalization. Simultaneous use was most common among those who used cannabis for recreational purposes only: 1 in 5 recreational only cannabis users simultaneously used alcohol and cannabis. This suggests that public health campaigns to discourage about simultaneous use of alcohol and cannabis (which is associated with higher risk of drunk driving, self-harm and other negative outcomes24), should focus on those who self-identify as recreational cannabis users. This finding also suggests that results of analyses of medicinal cannabis laws may not accurately predict alcohol use under legalization, as the behaviour of individuals who use predominantly for medicinal purposes may be quite different from that of those who use recreationally.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This paper was written with support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant Number: 3R01 DA032693-03S1). We are grateful for helpful comments from our colleagues Beau Kilmer, Priscillia Hunt, and two anonymous referees.

Footnotes

Author contributions: All authors contributed significantly to the content, writing, and editing of the document so that it would represent a true synthesis of our combined understanding of the relevant cannabis policy and public health literatures.

In the United States, the term “marijuana” is more commonly used to reference various cannabis material, and hence survey questions (and the name of the survey) reflect the common nomenclature used here.

Declaration of interests: The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. This research was done with support from a NIDA grant. RLP had full access to all survey data and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Contributor Information

Rosalie Pacula, Drug Policy Research Center - RAND, 1776 Main Street, PO Box 2138, Santa Monica, California CA 90407-2138, United States, pacula@rand.org.

Mireille Jacobson, University of California, Irvine - Business School, Irvine, California, United States.

Ervant J Maksabedian, RAND - Pardee RAND Graduate School, Santa Monica, California, United States.

References

- 1.Kleber HD, DuPont RL. Physicians and medical marijuana. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;169(6):564–568. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen PJ. Medical marijuana 2010: it's time to fix the regulatory vacuum. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2010;38(3):654–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2010.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DuPont RL. Examining the debate on the use of medical marijuana. Proceedings of the Association of American Physicians. 1999;111(2):166–172. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1381.1999.09252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogborne AC, Smart RG, Adlaf EM. Self-reported medical use of marijuana: a survey of the general population. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2000;162(12):1685–1686. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware MA, Adams H, Guy GW. The medicinal use of cannabis in the UK: results of a nationwide survey. International journal of clinical practice. 2005;59(3):291–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan-Ibarra S, Induni M, Ewing D. Prevalence of medical marijuana use in California, 2012. Drug and alcohol review. 2014;34(2):141–146. doi: 10.1111/dar.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh Z, Callaway R, Belle-Isle L, Capler R, Kay R, Lucas P, Holtzman S. Cannabis for therapeutic purposes: Patient characteristics, access, and reasons for use. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2013;24(6):511–516. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nunberg H, Kilmer B, Pacula RL, Burgdorf JR. An analysis of applicants presenting to a medical marijuana specialty practice in California. Journal of drug policy analysis. 2011;4(1) doi: 10.2202/1941-2851.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Connell TJ, Bou-Matar CB. Long term marijuana users seeking medical cannabis in California (2001-2007): demographics, social characteristics, patterns of cannabis and other drug use of 4117 applicants. Harm Reduction Journal. 2007;4(16) doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogborne AC, Smart RG, Weber T, Birchmore-Timney C. Who is using cannabis as a medicine and why: an exploratory study. Journal of psychoactive drugs. 2000;32(4):435–443. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furler MD, Einarson TR, Millson M, Walmsley S, Bendayan R. Medicinal and recreational marijuana use by patients infected with HIV. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2004;18(4):215–228. doi: 10.1089/108729104323038892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woolridge E, Barton S, Samuel J, Osorio J, Dougherty A, Holdcroft A. Cannabis use in HIV for pain and other medical symptoms. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2005;29(4):358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prentiss D, Power R, Balmas G, Tzuang G, Israelski DM. Patterns of marijuana use among patients with HIV/AIDS followed in a public health care setting. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;35(1):38–45. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware MA, Doyle CR, Woods R, Lynch ME, Clark AJ. Cannabis use for chronic non-cancer pain: results of a prospective survey. Pain. 2003;102(1):211–216. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00400-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark AJ, Ware MA, Yazer E, Murray TJ, Lynch ME. Patterns of cannabis use among patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62(11):2098–2100. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127707.07621.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page SA, Verhoef MJ. Medicinal marijuana use: experiences of people with multiple sclerosis. Canadian Family Physician. 2006;52(1):64–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hazekamp A, Ware MA, Muller-Vahl KR, Abrams D, Grotenhermen F. The medicinal use of cannabis and cannabinoids—an international cross-sectional survey on administration forms. Journal of psychoactive drugs. 2013;45(3):199–210. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2013.805976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malanick CE, Pebley AR, editors. Data priorities for population and health in developing countries: summary of a workshop. National Academies; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. Debilitating conditions for medical marijuana use. Medical Marijuana Registry. Available at: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/CHEIS_MMJ_Debilitating-Medical-Conditions.pdf.

- 20.Oregon Health Authority. Public Health Division Oregon Medical Marijuana Program (OMMP) P.O. Box 14450 Portland, OR 97293-0450: The Oregon Medical Marijuana Program. Available at: https://public.health.oregon.gov/DiseasesConditions/ChronicDisease/MedicalMarijuanaProgram/Documents/ommpHandbook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Washington State Department of Health. Medical Marijuana Program. P.O. Box 47852, Olympia, WA 98504-7852: Washington State Medical Marijuana Authorization Form. Available at: http://www.doh.wa.gov/Portals/1/Documents/Pubs/630123.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Legislature Of The State Of New Mexico. New Mexico Medical Cannabis Program. New Mexico Department of Health; The Lynn And Erin Compassionate Use Act. Available at: http://nmhealth.org/publication/view/regulation/128/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Earleywine M, Newcomb MD. Concurrent versus simultaneous polydrug use: prevalence, correlates, discriminant validity, and prospective effects on health outcomes. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 1997;5(4):353. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MS, Kerr WC. Simultaneous versus concurrent use of alcohol and cannabis in the National Alcohol Survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:872–879. doi: 10.1111/acer.12698. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acer.12698/epdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.