Abstract

Introduction

Periadnexal adhesions are known to contribute to subfertility. The restoration of the tubo-ovarian anatomy is one the key principles in reproductive surgery, and this involves adhesiolysis. However, adhesion formation/reformation is very common after periovarian adhesiolysis. It is not known if the application of Hyalobarrier®, an anti-adhesion gel, around the adnexal region postsurgery influences ovulatory status. The study is a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) randomizing women into the application of Hyalobarrier® versus no Hyalobarrier® at the time of laparoscopy, where postsurgical ovulatory status and pregnancy rates were evaluated.

Methods

This was a pilot RCT where women were recruited from the gynecological and subfertility clinic who were deemed to require an operative laparoscopy. If intraoperatively they were found to have periovarian adhesions, they were randomized into having adhesiolysis with and without usage of Hyalobarrier®. Demographic details and intraoperative details including the severity, extent, and the ease of use of Hyalobarrier® were recorded. Prior to the surgery and postoperatively, the participants had their serum hormonal status (day 2 FSH, LH and day 21 progesterone) evaluated. Postoperatively, they underwent a follicular tracking cycle at 3 months.

Results

Fifteen women were randomized into use of Hyalobarrier® (study group) and 15 into the no Hyalobarrier® group (control group) between December 2011 and January 2014. There was no difference in the patient characteristics in terms of age, BMI, the number of previous pregnancies, or the extent, site, and severity of adhesions between the two groups. There was no significant difference between the study versus control groups in terms of the hormonal profile (day 2 FSH and day 21 progesterone) before or after surgery. The 3-month postoperative day 10–12 follicular tracking findings and endometrial thickness were similar between the study and control groups. Four women were pregnant in the study group (24%) and one in the control group (7%) cumulatively over 2 years.

Conclusion

The use of Hyalobarrier® post salpingo-ovariolysis did not influence follicular development as inferred from the results of the day 21 progesterone and folliculogram on day 10–12 3-month postsurgery.

Trial Registration

ISRCTN number, ISRCTN1833588.

Funding

Nordic Pharma.

Keywords: Adhesiolysis, Fertility, Hyalobarrier, Ovary, Adhesion prevention

Introduction

Periadnexal adhesions are adhesions which envelop the fimbriae ends, the Fallopian tubes, and/or ovaries. These adhesions can develop postsurgically, after infection and inflammation secondary to pelvic inflammatory disease or as a consequence of other intra-abdominal infective sources. Periadnexal adhesions contribute to subfertility by a combination of ways, namely by the mechanical distortion of the tubo-ovarian anatomy thereby interfering with the transport of the ovum into the Fallopian tube or the disruption of blood supply to the ovary and its follicular development [1–4]. Indeed, it has been observed that women with periovarian adhesions are significantly more prone to have unruptured follicles [5].

The restoration of the tubo-ovarian anatomy is one of the key principles in reproductive surgery, and this involves adhesiolysis. However, adhesion formation/reformation is very common after periovarian adhesiolysis (40%) [6]. The natural anatomical position and density of ovaries preclude the hydrofloatation mechanism as an effective adhesion prevention strategy after adnexal surgery [7]. Hence, consideration is required for the application of other forms of adhesion prevention agents such as hyaluronic gel-based products.

Hyalobarrier® Gel Endo is a sterile, transparent, and highly viscous gel that forms a barrier to prevent or reduce postsurgical adhesions. A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining if the intrauterine instillation of Hyalobarrier® after the evacuation of products of conception showed a significant reduction in the formation of intrauterine adhesions postoperatively at second-look hysteroscopy [8]. The gel is composed of highly purified, auto-crosslinked polymers of hyaluronic acid. Hyaluronic acid is a main component of the connective tissue in the human body. When applied between tissue surfaces, it ensures that adhesive surfaces of the peritoneum in the ovarian fossae are separated and thus is theoretically effective in periovarian postoperative adhesion prevention. Within the peritoneum, this gel-based product is required to be placed on and adjacent to the ovaries and Fallopian tubes, and the immediate impact on ovulatory function and subsequent reproductive outcome is unclear.

The study is a pilot RCT randomizing women into the application of Hyalobarrier® versus no Hyalobarrier® at the time of laparoscopy once the surgeon confirmed the presence of salpingo-ovarian adhesions and proceeded to perform salpingo-ovariolysis. The ovarian function of women with periovarian adhesiolysis who had Hyalobarrier® as an anti-adhesion barrier instilled and those who did not was compared. The clinical pregnancy rates of the two groups of women were also evaluated at 2 years postoperatively.

Methods

This was a pilot RCT where women were recruited from the gynecological and subfertility clinic who were deemed to require an operative laparoscopy. If intraoperatively they were found to have periovarian adhesions, they were randomized into having adhesiolysis with Hyalobarrier® (study group) and without usage of Hyalobarrier® (control group).

The inclusion criteria were (1) age 18–38 years; (2) women undergoing operative laparoscopy for gynecological pathology, with possible periovarian adhesions. The exclusion criteria were the (1) presence of malignancies or a history of malignancies; (2) women on medications that affected ovulation; and (3) women with known conditions that resulted in anovulation (PCOS, pituitary causes).

The method of conduct of this RCT is similar to studies previously conducted by our group [9]. Randomization was performed using computer-generated random numbers and the concealed, opaque, unlabeled envelope was opened after it had been determined that the patient met the intraoperative criteria. The patients were blinded to the allocation of treatment, and the assessor during follow-up was blinded to the treatment. The assessor who administered the questionnaires and recruited the patients was the research nurse who did not have prior knowledge of what type of surgery the patients underwent. Consent was obtained prior to any baseline assessments. The operation notes were stored in a sealed envelope within the patient notes and not accessed except during an emergency. In the latter case, the data would be used to the point of unblinding. The randomization code was broken at the end of the follow-up period, and patients who wished to know were informed of their treatment groups.

Laparoscopic surgeons who were skilled in advanced laparoscopy performed the surgery. Entry into the abdomen was either via the traditional Veress needle or a modified Hasson’s technique of open entry. CO2 was used for creating a pneumoperitoneum of 20 mmHg before a 10-mm trocar was inserted into the intraumbilical incision. Two or three more lateral ports were inserted depending on the site and extent of surgery. During surgery, the principles of microsurgery were followed, including meticulous hemostatic control and usage of constant irrigation to prevent tissue desiccation. Hyalobarrier® was applied to women randomized intraoperatively to the study group, and no Hyalobarrier® was applied to the group randomized to the control group. Ten milliliters of Hyalobarrier® Gel Endo was applied using the standard applicator in the commercial pack over the operative site(s). A short questionnaire on the ease of use of the Hyalobarrier® was completed by the surgeon postoperatively. The questions included were (1) if the gel was applied, (2) the ease of application during surgery (range from very poor, poor, fair, good, and very good), (3) if the surgeons would use the gel again in the next appropriate surgery, and (4) any other general feedback.

The patients’ histories, clinical examination, and operative findings were documented on standard proforma. The extent, severity, and site of adhesions were noted and the completeness of adhesiolysis was documented. The extent of the adhesions was defined as no adhesions, mild (adhesions covering less than 26% of total area), moderate (adhesions covering 26–50% of total area), and severe (adhesions covering at least 51% of total area). The severity of adhesions was defined as no adhesions, mild (filmy and avascular adhesions), moderate (some vascularity and/or dense adhesions), and severe (cohesive) adhesions. All patients’ data and including hormonal and follicular tracking results were entered into a computerized database. Complications during and after the surgery were documented on standard proforma sheets.

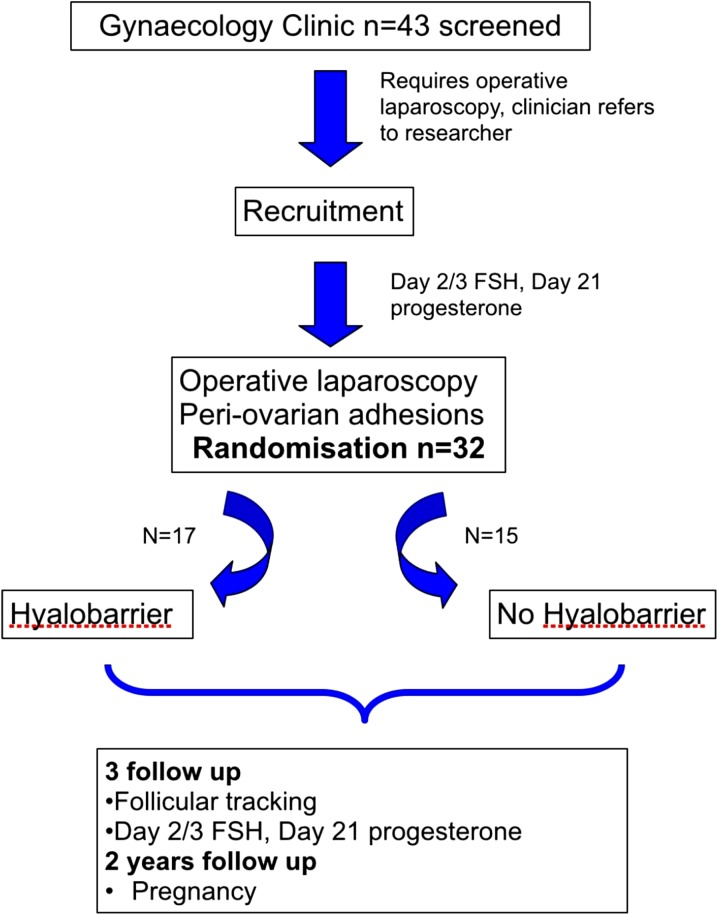

Prior to the surgery, and postoperatively, the participants had their serum hormonal status (day 2 FSH, LH and day 21 progesterone) evaluated. Postoperatively, they underwent a follicular tracking cycle at 3 months. Ovulation was compared as a continuous outcome of day 21 progesterone levels with follicular scan performed on day 10–12 used as supportive evidence. The patient flow of this trial is as per Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the patient flow of the trial

Statistical Analysis

Given that adhesion reformation is significant after adnexal surgery (up to 90%), taking the mean of day 21 progesterone (±SD) for the control group to be 33 (7) nmol/l and the study group to be 51 (15.7) [5], the sample size for each group required to show a statistical significance at the p = 0.05 level between the study and control groups was calculated to be n = 15 (total sample size = 30).

The outcome measures were postoperative day 2/3 FSH, LH, day 21 progesterone, evidence of follicular development during follicular tracking at day 10–14, and clinical pregnancy defined as the presence of a fetal heart at the 6-week scan.

The data analysis was performed using SPSS. T test comparisons will be used for continuous variables, and Chi2 for discrete variables.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The ethics number of this study was 11/H0504/6 and the ISRCTN number was ISRCTN1833588. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

This research conformed to the CONSORT guidelines.

Results

A total of 43 women were screened and 15 were randomized into the study group and 15 into the control group between December 2011 and January 2014. There was no difference in the patient characteristics (Tables 1, 2, 3) in terms of age, BMI, the number of previous pregnancies, or the extent, site, and severity of adhesions between the two groups. None of the patients had endometriosis.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics of patients between the study (Hyalobarrier®) and control (no Hyalobarrier®) groups

| Patient characteristics | Hyalobarrier® (n = 15) | No Hyalobarrier® (n = 15) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 32.7 ± 4.7 | 31.5 ± 3.8 | NS |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 23.4 ± 2.8 | 24.0 ± 3.9 | NS |

| Number of previous surgeries (mean ± range) | 0.8 (0–5) | 0.8 (0–4) | NS |

| Number of previous pregnancies (mean ± range) | 0.9 (0–4) | 1.1 (0–9) | NS |

NS not significant

Table 2.

Number of patients with adhesions at the various sites within the pelvis

| Adhesion sites | Hyalobarrier® (n = 15) | No Hyalobarrier® (n = 15) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | 2 | 2 | NS |

| Posterior uterus | 3 | 2 | NS |

| Adnexal adhesions | 51 | 53 | NS |

NS not significant

Table 3.

Severity and extent of adhesions in the comparison groups

| Adhesion severity and extent | Hyalobarrier® (n = 15) | No Hyalobarrier® (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 12 | 7 |

| Moderate | 1 | 8 |

| Severe | 2 | 0 |

There was no significant difference in the mean ± SD between the study versus control groups in terms of the hormonal profile (day 2 FSH and day 21 progesterone) before or after surgery (Table 3). The 3-month postoperative day 10–12 follicular scan showed similar development of mature follicles in the study group (mean diameter of follicle 18.1 ± 3.9 mm) and the control group (mean diameter of follicle 19.8 ± 5.6 mm). There was also no difference in the endometrial thickness in the study (10.4 ± 2.2 mm) versus the control group (8.7 ± 0.6 mm) at the 3-month scan postoperatively (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Hormonal and ultrasound results in the Hyalobarrier® and no Hyalobarrier® groups

| Patient characteristics | Hyalobarrier® | No Hyalobarrier® | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presurgery day 2 FSH | 7.2 ± 2.4 | 6.24 ± 1.5 | 0.22 |

| Presurgery day 21 progesterone | 27.3 ± 14.8 | 32.2 ± 17.5 | 0.31 |

| Postsurgery FSH | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 0.19 |

| Postsurgery day 21 progesterone | 17.4 ± 13.3 | 24.1 ± 11.3 | 0.37 |

| Postsurgery day 10–12 follicular scan | 18.1 ± 3.9 | 19.8 ± 5.6 | 0.78 |

| Postsurgery endometrial thickness | 10.4 ± 2.2 | 8.7 ± 0.6 | 0.28 |

Four women were pregnant in the study group (24%) and one in the control group (7%) cumulatively over 2 years. Amongst the pregnant patients in the study group, there were three spontaneous pregnancies within 18 months postsurgery and one pregnancy following an in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment. In the control group, one woman was spontaneously pregnant within 12 months of surgery.

The majority of surgeons reported that the Hyalobarrier® Gel Endo was easy to apply. There was one questionnaire which was not returned.

Discussion

The use of Hyalobarrier® post salpingo-ovariolysis did not influence follicular development as inferred from the results of the day 21 progesterone and folliculogram on day 10–12 3-month postsurgery. This finding will need to be confirmed in larger studies; however, preliminary data suggests that the application of the Hyalobarrier® is not detrimental to follicular development as denoted by follicular scan and hormonal evaluation postoperatively.

Reproductive surgeons and gynecologists are often confronted with the conundrum of whether or not to remove adhesions around the adnexal area involving the Fallopian tubes and ovaries, in the presence of apparently patent Fallopian tubes. This dilemma is in part resolved with the advent of IVF technology, where fully functional Fallopian tubes are not required for conception, and hence intraoperatively, if IVF was thought to be a viable option for the patient, that their adnexal adhesions are often left unlysed to save operative time and unnecessary operative complications. Unfortunately, whilst IVF offers a real and tangible option for a successful conception, the pregnancy rate per cycle is stagnated at around 30% per cycle (Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, HFEA). The UK National Health Service (NHS) publicly funds limited numbers of IVF cycles. The cost of a private cycle of IVF often prohibits a significant number of patients accessing this treatment for conception. This means that in real terms, about two-thirds of patients who did not manage to achieve a pregnancy after their IVF treatment will continue to suffer from infertility. The latter further emphasizes the complementary nature of surgery to IVF.

Traditionally in reproductive surgery, adnexal adhesions can be managed by adhesiolysis. It has been reported that the cumulative pregnancy rate 1 year after adhesiolysis can be as high as 67%, although a substantial number of patients were observed to have adhesion reformation at second-look laparoscopy [10]; but the increased risk of ectopic pregnancy remains high, especially if salpingostomy was also performed [11].

However, there are few data on the effects of these agents on fertility and pregnancy outcomes whether when applied intra-abdominally or intrauterine [12]. Very often, RCTs on these agents evaluate end points pertaining to adhesion reformation rather than pregnancy outcomes [13]. No studies have examined the postsurgical ovulatory status, endometrial thickness, and the clinical pregnancy rates after application of the anti-adhesion gel around the adnexal region(s). Our study suggests that there is no difference between the ovulatory status and endometrial development of women who had the Hyalobarrier® gel applied intraoperatively versus those who had not, as observed from day 21 progesterone hormonal profile and follicular tracking scans performed at 3 months postoperatively.

Whilst this study did not provide second-look adhesion formation data, adhesion formation post application of the Hyalobarrier® gel has been evaluated after other forms of gynecological surgery [8, 14] with some evidence of benefit. As the anti-adhesion gel is easy to use, surgeons should consider the application of anti-adhesion treatment around the adnexal region after salpingo-ovariolysis and adhesiolysis in relation to adhesive pelvic disorders [15, 16] to reduce the incidence of postoperative adhesions.

The limitations of this study include the small sample size. Future larger RCTs powered to assess pregnancy rates and time to pregnancy as the primary endpoint will be important to further evaluate the fertility aspects of using anti-adhesion barriers following salpingo-ovariolysis and adhesiolysis in relation to adhesive pelvic disorders.

Conclusion

Preliminary data suggests that the application of the Hyalobarrier® is not detrimental to follicular development as denoted by follicular scan and hormonal evaluation postoperatively. Surgeons should consider the application of anti-adhesion treatment around the adnexal region after salpingo-ovariolysis and adhesiolysis in relation to adhesive pelvic disorders to reduce the incidence of postoperative adhesions.

Acknowledgements

This study was an investigator-led study funded by Nordic Pharma. Sponsorship for this study, article processing charges, and the open access fee were funded by Nordic Pharma. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. YC conceived the idea, design the study, analyzed the data, wrote the manuscript. SB and JF conducted the study, wrote and edited the manuscript.

Disclosures

Ying Cheong is the recipient of the Nordic grant for this study. This study was an investigator-led study with the support of an education grant from Nordic Pharma. Sarah Bailey and Jane Forbes has nothing to disclose.

Compliance to Ethics Guidelines

The ethics number of this study was 11/H0504/6 and the ISRCTN number was ISRCTN1833588. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. This research conformed to the CONSORT guidelines.

Data Availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/D527F06018B08E8F.

References

- 1.Caspi E, Halperin Y. Surgical management of periadnexal adhesions. Int J Fertil. 1981;26(1):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahadevan MM, et al. The effects of ovarian adhesive disease upon follicular development in cycles of controlled stimulation for in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1985;44(4):489–492. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)48917-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman MC, Cooke ID, Lenton EA. Investigation of impaired ovarian function as a contributing factor to infertility in women with pelvic adhesions. Hum Reprod. 1993;8(10):1654–1656. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagata Y, et al. Peri-ovarian adhesions interfere with the diffusion of gonadotrophin into the follicular fluid. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(8):2072–2076. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.8.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilton CJ, Evers JL, Hoogland HJ. Ovulatory disorders and inflammatory adnexal damage: a neglected cause of the failure of fertility microsurgery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;93(3):282–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1986.tb07909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alborzi S, Motazedian S, Parsanezhad ME. Chance of adhesion formation after laparoscopic salpingo-ovariolysis: is there a place for second-look laparoscopy? J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(2):172–176. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter TT, Kent A. Ovaries do not float. Gynecol Surg. 2004;1(4):263–264. doi: 10.1007/s10397-004-0066-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooker A, et al. Prevention of adhesions post (spontaneous) abortion (PAPA study); a randomized controlled trial evaluating application of hyaluronic acid (HA) Hum Reprod. 2016;31(Supp 1):39. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheong YC, et al. Should women with chronic pelvic pain have adhesiolysis? BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):36. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tulandi T, Falcone T, Kafka I. Second-look operative laparoscopy 1 year following reproductive surgery. Fertil Steril. 1989;52(3):421–424. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)60911-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomel V. Salpingo-ovariolysis by laparoscopy in infertility. Fertil Steril. 1983;40(5):607–611. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)47418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bosteels J, et al. Anti-adhesion barrier gels following operative hysteroscopy for treating female infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2014;11:113–127. doi: 10.1007/s10397-014-0832-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad G, et al. Barrier agents for adhesion prevention after gynaecological surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(4):CD000475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Metwally M, Cheong Y, Li TC. A review of techniques for adhesion prevention after gynaecological surgery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20(4):345–352. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283073a6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Wilde RL, et al. Adhesions and endometriosis: challenges in subfertility management: (an expert opinion of the ANGEL-The ANti-Adhesions in Gynaecology Expert PaneL-group) Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294(2):299–301. doi: 10.1007/s00404-016-4049-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.RCOG. The use of adhesion prevention agents in obstetrics and gynaecology (Scientific Impact Paper no. 39). London: Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists; 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.