Abstract

Introduction

Regulatory requirements mandate that new drugs for treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), such as dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, are evaluated to show that they do not increase cardiovascular (CV) risk.

Methods

A systematic review was undertaken to evaluate the association between DPP-4 inhibitor and GLP-1 receptor agonist use and major adverse cardiac events (MACE). The National Institutes of Health Medline database was searched for pooled analyses, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists that included CV endpoints.

Results

Thirty-six articles met the inclusion criteria encompassing 11 pooled analyses, 17 meta-analyses, and eight RCTs (including secondary analyses). Over the short term (up to 4 years), patients with T2DM exposed to a DPP-4 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist were not at increased risk for MACE (or its component endpoints) compared with those who received comparator agents. Two meta-analyses showed a significant reduction in the incidence of MACE associated with DPP-4 inhibitor therapy as a drug class, but this beneficial effect was not observed in other meta-analyses that included large RCT CV outcome studies. In four RCTs that evaluated alogliptin, saxagliptin, sitagliptin, or lixisenatide, there was no overall increased risk for MACE relative to placebo in T2DM patients at high risk for CV events or with established CV disease, although there was an increased rate of hospitalization for heart failure associated with saxagliptin. A fifth RCT showed that liraglutide reduced MACE risk by 13% versus placebo.

Conclusion

Overall, incretin therapy does not appear to increase risk for MACE in the short term.

Keywords: Cardiovascular risk, Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, MACE, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) significantly increases risk for cardiovascular (CV) disease [1]. Strategies for the management of CV risk factors are therefore essential to reduce CV morbidity and mortality associated with T2DM [1, 2].

While clinical trials have provided some evidence that intensive glucose control in patients with T2DM may reduce risk for myocardial infarction (MI) and other major adverse cardiac events (MACE), this is not the case for all-cause mortality [3, 4]. The attendant heightened risk for severe hypoglycemia with intensive glucose-lowering treatment has been postulated to be a significant counterbalance to CV benefit [5]. Indeed, hypoglycemia and other undesired adverse events (AEs) associated with glucose-lowering drugs may be especially deleterious in older, more frail patients with multiple comorbidities [4]. Therefore, while stringent glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) targets may be appropriate in some patients with T2DM, comprehensive care is increasingly regarded as requiring an individualized approach that includes treatment of all CV risk factors, not just hyperglycemia [1]. Drugs with a good tolerability profile that do not induce hypoglycemia may be compatible with strict glycemic targets even in frail patients.

The two classes of incretin-based therapies, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, can achieve reductions in HbA1c without substantive risk for hypoglycemia [1]. As the use of these drugs in the management of T2DM has increased [1], so too has interest in their potential capacity to modify CV risk, either detrimentally or beneficially.

Following concerns over the cardiac safety of rosiglitazone and other antidiabetic drugs in 2008 [6], current regulatory guidance now requires that new drugs for the treatment of patients with T2DM must withstand long-term and large-scale assessment of CV safety [7]. The United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) may approve an antidiabetic agent if integrated analysis of completed studies demonstrates that its upper 95% confidence interval (CI) limit for the estimated risk ratio (RR) for MACE is less than 1.3 versus comparator. If, however, the upper bound is between 1.3 and 1.8, sponsors must subsequently demonstrate CV safety in post-marketing CV outcomes trials [7].

Preclinical data and mechanistic studies of DPP-4 inhibitors suggest possible additional nonglycemic beneficial actions on blood vessels and the heart, via both GLP-1-dependent and GLP-1-independent effects [8, 9]. Positive effects of DPP-4 inhibitors on the myocardium have also been described in patients with ischemic heart disease [8]. In patients with T2DM, DPP-4 inhibitors may improve total cholesterol and triglyceride levels [10], reduce inflammatory markers, oxidative stress, and platelet aggregation, improve endothelial function [8, 9], and increase circulating endothelial progenitor cells possibly promoting vascular repair [11]. In addition, DPP-4 inhibitors are weight neutral [8].

Likewise, GLP‐1 receptor agonists exert pleiotropic effects on the CV system beyond glycemic control. Overall, GLP‐1 receptor agonists have a beneficial effect on traditional CV risk factors [12], and reduce body weight in overweight or obese patients [13, 14]. Treatment with GLP‐1 receptor agonists in patients with T2DM is associated with a reduction in blood pressure, which precedes weight loss [15]. Furthermore, longer-term studies have also reported some improvements in lipid profile [16], which could be the consequence of body weight reduction. It has been suggested that the direct stimulation of GLP‐1 receptors in the vasculature and myocardium could produce further benefits on CV risk [17]. Conversely, some clinical trial data indicate that treatment with GLP‐1 receptor agonists can produce a modest increase in heart rate [18], which may potentially be associated with a higher CV risk [19].

By conducting a systematic literature review of integrated analyses and randomized controlled studies specifically designed to assess MACE, we have further examined the relationship between incretin therapies and CV risk in patients with T2DM.

Methods

This systematic review is reported in line with the criteria stipulated in the PRISMA statement [20]. To identify published clinical data on the CV safety of incretin-based therapies in T2DM, we conducted searches of the US National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health Medline database as of the June 21, 2016.

First, we searched for meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists that reported CV events, and pooled analyses of patient-level data from randomized controlled trials of individual DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists that reported CV events. Delimited by English language, the search terms and Boolean strategy were as follows: ((alogliptin OR linagliptin OR saxagliptin OR sitagliptin OR vildagliptin OR “dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors” OR “DPP-4 inhibitors” OR gliptins) OR (exenatide OR liraglutide OR albiglutide OR taspoglutide OR dulaglutide OR lixisenatide OR semaglutide OR “glucagon-like peptide‐1 receptor agonists” OR GLP-1)) AND cardiovascular AND (“pooled analysis” OR “comprehensive analysis” OR “meta-analysis” OR “integrated analysis” OR “systematic review” OR “systematic assessment” OR “indirect comparison”). The authors screened the title and abstract of each retrieved article for relevance following which full-text articles were obtained and reviewed qualitatively for final inclusion and assessment. Articles solely reporting data on surrogate CV endpoints (e.g., plasma lipids and blood pressure) were excluded. Articles reporting analyses with significant overlap (e.g., updated meta-analyses including the same randomized controlled trials) were excluded. In the case of overlap, the paper reporting the largest dataset was included. For the purpose of this review, a pooled analysis was defined as analysis of combined study data without weighting (i.e., as if the data were derived from a single sample) and a meta-analysis was defined as an analysis of combined study data after data from each study had undergone weighting.

Second, we searched for randomized controlled trials using Boolean logic and the aforementioned drug terms combined with the term “cardiovascular” and the terms “randomized OR randomised OR randomly”. Returned articles were reviewed qualitatively. To qualify for inclusion, only randomized controlled trials reporting CV outcomes as the primary endpoint were selected. Duplicate articles (i.e., articles reporting the same trial) were excluded.

This systematic review was undertaken to assess the effects of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists on MACE with emphasis on MI, stroke, CV death, and hospitalizations for acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and heart failure (HF) (or ACS and HF reported as severe AEs). For each analysis, the total number of MACE reported for individual incretins and comparator therapy is reported, from which exposure-adjusted incidence rates per 100 patient-years have been compiled. Our primary objective was to report on the base-case RR of patients having a CV-related event whilst receiving a DPP-4 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist versus all comparator therapies. The RR estimates calculated by use of other statistical methods and via sensitivity analyses are reported on an individual study-by-study basis, as they complement base-case analyses. Time to MACE represents an additional level of safety data and is reported when possible. A secondary objective of our review was to explore via subgroup analysis the possibility that various factors influence MACE RR. Finally, to identify possible reasons for discrepancies in results between the integrated analyses and CV outcome studies, extracted baseline patient data for relevant articles have been compared.

This article is based on previously conducted studies, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Literature Review

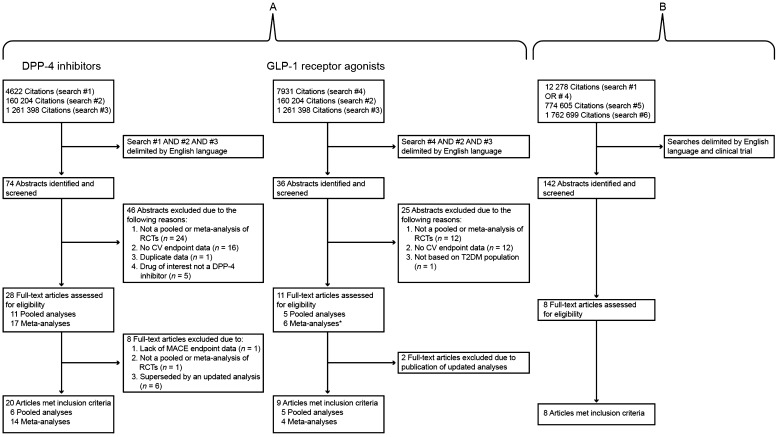

Regarding meta-analyses of trial-level data and pooled analyses of patient-level data, searches yielded 109 articles, consisting of 74 articles concerning DPP-4 inhibitors and 36 articles concerning GLP-1 receptor agonists (one meta-analysis of trial-level incretin therapy data was identified in both searches) (Fig. 1a). On the basis of the article abstracts, 71 articles were dismissed primarily because an integrated analysis of randomized controlled trial data or CV endpoint data was not reported. Thus, 38 full-text articles were retrieved and further reviewed for eligibility (Table 1), after which 28 articles met inclusion criteria and were assessed further (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Individual flow diagrams of included studies. Search #1 = alogliptin OR linagliptin OR saxagliptin OR sitagliptin OR vildagliptin OR “dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors” OR “DPP-4 inhibitors” OR gliptins; Search #2 = “pooled analysis” OR “comprehensive analysis” OR “meta-analysis” OR “integrated analysis” OR “systematic review” OR “systematic assessment” OR “indirect comparison”; Search #3 = cardiovascular; Search #4 = exenatide OR liraglutide OR albiglutide OR taspoglutide OR dulaglutide OR lixisenatide OR semaglutide OR “glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists” OR GLP-1; Search #5 = randomized OR randomised OR randomly; Search #6 = cardiovascular or heart [field: Title/abstract]. *Included one pairwise and network meta-analysis. CV cardiovascular, DPP-4 dipeptidyl peptidase-4, GLP-1 glucagon-like peptide-1, RCTs randomized controlled trials, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

Table 1.

Search results: pooled analyses of patient-level data and meta-analyses of trial-level data from studies investigating DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists

| First author, year of publication | References | Drug(s) assessed | Publication type | Met inclusion criteriaa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPP-4 inhibitors | ||||

| Abbas, 2016 | [42] | Alogliptin, saxagliptin, and sitagliptin | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Agarwal, 2014 | [33] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Cobble, 2012 | [66] | Saxagliptin | Narrative review | No |

| Engel, 2013 | [23] | Sitagliptin | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Frederich, 2010 | [67] | Saxagliptin | Pooled analysis | No |

| Iqbal, 2014 | [24] | Saxagliptin | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Johansen, 2012 | [68] | Linagliptin | Pooled analysis | No |

| Kongwatcharapong, 2016 | [38] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Kundu, 2016 | [39] | Alogliptin, sitagliptin, and saxagliptin | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Lehrke, 2014 | [22] | Linagliptin | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Li, 2016 | [40] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| McInnes, 2015 | [25] | Vildagliptin | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Monami, 2011 | [69] | Allb | Meta-analysis | No |

| Monami, 2012 | [10] | Allb | Meta-analysis | No |

| Monami, 2013 | [29] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Monami, 2014 | [34] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Patil, 2012 | [30] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Rosenstock, 2015 | [21] | Linagliptin | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Savarese, 2015 | [36] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Schweizer, 2010 | [64] | Vildagliptin | Pooled analysis | No |

| Udell, 2015 | [37] | Alogliptin and saxagliptin | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| von Eynatten, 2013 | [70] | Linagliptin | Pooled analysis | No |

| Wang, 2016 | [41] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| White, 2013 | [26] | Alogliptin | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Williams-Herman, 2010 | [71] | Sitagliptin | Pooled analysis | No |

| Wu, 2013 | [31] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Wu, 2014 | [35] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Zhang, 2014 | [32] | Allb | Meta-analysis | Yesc |

| GLP-1 receptor agonists | ||||

| Ferdinand, 2016 | [54] | Dulaglutide | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Fisher, 2015 | [53] | Albiglutide | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Li, 2016 | [56] | Alld | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Marso, 2011 | [50] | Liraglutide | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Monami, 2009 | [72] | Alld | Meta-analysis | No |

| Monami, 2011 | [73] | Alld | Meta-analysis | No |

| Monami, 2013 | [12] | Alld | Meta-analysis | Yes |

| Ratner, 2011 | [51] | Exenatide | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Seshasai, 2015 | [52] | Taspoglutide | Pooled analysis | Yes |

| Sun, 2012 | [55] | Alld | Pairwise and network meta-analysis | Yes |

| Wang, 2016 | [41] | Albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide | Meta-analysis | Yes |

aPooled analyses and meta-analyses meeting inclusion criteria were those that reported CV events as a primary objective. All excluded papers were rejected on the basis that CV events were not explicitly reported (including papers containing no analysis of adverse events), or were rendered redundant because of updated analyses

bAlogliptin, linagliptin, saxagliptin, sitagliptin, vildagliptin ± dutogliptin

cDescribed CV events in general, which included MACE

dExenatide, liraglutide, albiglutide, taspoglutide, dulaglutide, lixisenatide ± semaglutide

Table 2.

Study-level features of the integrated analyses describing the CV safety of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists trialled in randomized controlled studies

| References | Incretin (dosage regimen) | No. of studies | Minimum trial duration (weeks) | Mean trial duration (weeks) | Analysis design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbas, 2016 [42] |

Alogliptin 6.25–25 mg/daya; sitagliptin 100 mg/dayb; saxagliptin 2.5–5 mg/dayc |

3 | – | 130d | Post hoc |

| Engel, 2013 [23]e | Sitagliptin (100 mg/day) | 25 | 12 | 34 | Post hoc |

| Iqbal, 2014 [24]f | Saxagliptin (2.5, 5, and 10 mg/day)g | 20 | 4 | 59 |

Post hoc (8 studies) Prespecified (12 studies) |

| Kundu, 2016 [39] |

Alogliptin 6.25–25 mg/daya; sitagliptin 100 mg/dayb; saxagliptin 2.5–5 mg/dayc |

3 | – | – | Post hoc |

| Lehrke, 2014 [22] | Linagliptin 5 mg/dayh | 22 | <2i | 22 | Post hoc |

| McInnes, 2015 [25] | Vildagliptin (50 mg od and bd) | 37 | 12 | 50.3 versus 48.7j | Post hoc |

| Rosenstock, 2015 [21] | Linagliptin (≥5 mg/day) | 19 | 12 | 35 | Prespecified |

| White, 2013 [26]k | Alogliptin (≥12.5 mg/day) | 11 | 12 | 29 | Prespecified |

| Udell, 2015 [37] | Alogliptin 6.25–25 mg/daya; saxagliptin 2.5–5 mg/dayc | 2 | – | 93 | Post hoc |

| Agarwal, 2014 [33] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 82 | 24 | 44 | Post hoc |

| Kongwatcharapong, 2016 [38] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 54 | 12 | 59 | Post hoc |

| Li, 2016 [40] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 43 | 12 | 61 | Post hoc |

| Monami, 2013 [29] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 63 | 24 | 46 | Post hoc |

| Monami, 2014 [34] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 82 | 24 | 47 | Post hoc |

| Patil, 2012 [30] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 18 | 24 | 52 | Post hoc |

| Savarese, 2015 [36] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 94 | 12 | 29d | Post hoc |

| Wang, 2016 [41] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 68 | 24 | 24–52l | Post hoc |

| Wu, 2013 [31] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 8 | 18 | 43 | Post hoc |

| Wu, 2014 [35] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 50 | 24 | 45 | Post hoc |

| Zhang, 2014 [32] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 12 | 18 | NR | Post hoc |

| Fisher, 2015 [53] | Albiglutide (15–50 mg/week or 30 mg biweekly) | 9 | 16 | 104 | Prespecified |

| Ferdinand, 2016 [54] | Dulaglutide (0.1–1.5 mg/week) | 9 | 12 | 45 | Prespecified |

| Ratner, 2011 [51] | Exenatide (2.5, 5, and 10 µg bd) | 12 | 12 | 23 | Post hoc |

| Marso, 2011 [50]m | Liraglutide (0.045–3.0 mg/day) | 15 | 26 | NR | Post hoc |

| Seshasai, 2015 [52] | Taspoglutide 20 mg/week | 9 | 24 | 52 | Prespecified |

| Li, 2016 [56] | GLP-1 receptor agonists | 21 | 16 | 78 | Post hoc |

| Monami, 2013 [12] | GLP-1 receptor agonists | 25 | 24 | 42 | Post hoc |

| Sun, 2012 [55] | GLP-1 receptor agonists | 45 | 8 | 27 | Post hoc |

| Wang, 2016 [41]m | Albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, liraglutide, lixisenatide | 35 | 24 | 24–156 l | Post hoc |

bd twice daily, od once daily, NR not reported

a25 mg in patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 of body surface area; 12.5 mg in patients with an eGFR of 30 to <60 mL/min/1.73 m2; and 6.25 mg in patients with an eGFR of <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 [28]

bOr 50 mg daily if the baseline eGFR was ≥30 and <50 mL/min/1.73 m2 [44]

c2.5 mg daily in patients with an eGFR ≤ 50 mL/min/1.73 m2 [43]

dMedian

eDid not include data from TECOS [44]

fDid not include data from SAVOR-TIMI 53 [43]

g20, 40, or 100 mg/day was administered in one phase 2b study

hOne of the 22 studies tested linagliptin 2.5 mg/day

iNearly two-thirds of patients received treatment for at least 24 weeks [22]

jMean duration of exposure for vildagliptin versus comparators [25]

kDid not include data from EXAMINE [28]

lRange of medians for studies of each DPP-4 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist

mDid not include data from LEADER [57]

Eight of 142 citations were identified in relation to randomized controlled trials reporting CV outcomes as a primary endpoint, four of which concerned DPP-4 inhibitors and one which concerned a GLP-1 receptor agonist (Fig. 1b).

CV Risk of DPP-4 Inhibitors

Pooled Analyses

Features

Of 11 pooled analyses of individual gliptins that were assessed for eligibility, six were assessed further, including two analyses of linagliptin [21, 22], and one each for sitagliptin [23], saxagliptin [24], vildagliptin [25], and alogliptin [26]. Numbers, incidences, and RRs of MACE associated with linagliptin and sitagliptin were compared versus placebo, active comparators, and placebo and active comparators combined [21–23], whereas the CV safety profiles of saxagliptin, vildagliptin, and alogliptin were evaluated relative to all comparators combined only [24–26]. One study by Lehrke et al. of linagliptin versus placebo included patient-level data pertaining to CV AEs that were matched with respect to background therapy [22], whereas the other studies evaluated the MACE profile of DPP-4 inhibitors versus control without regard for concomitant antidiabetic background therapy [21, 23–26].

Sample size was largest for the pooled analysis of vildagliptin CV safety (n = 17,446) and lowest for the pooled analysis of alogliptin CV safety (n = 6028) (Table 3). Average follow-up time was less than 2 years across all analyses. Although the definitions of MACE utilized in the saxagliptin, linagliptin, vildagliptin, and alogliptin pooled analyses of composite endpoints did vary, they were broadly similar, encompassing CV death, MI, ACS, and stroke. The linagliptin pooled analysis of MACE by Rosenstock et al. was the only analysis to include hospitalization for unstable angina pectoris (UAP) in the composite endpoint [21], while the saxagliptin pooled analysis included ischemic events as an additional MACE component [24]. The examination of MACE and CV death in two pooled analyses of linagliptin and alogliptin were prespecified [21, 26], whereas these endpoints were evaluated post hoc for the other DPP-4 inhibitor analyses (Table 2), which potentially introduces bias and reduces the reliability of the data. The pooled analysis of sitagliptin was further limited in that it included a very broad MACE composite (comprising 39 MedDRA terms), which as a CV endpoint may be criticized because of its heterogeneous definition and combination of both safety and effectiveness endpoints [27], and did not feature an independent process to adjudicate instances of MACE [23]. Likewise, the linagliptin post hoc pooled analysis by Lehrke et al. assessed CV AEs based on MedDRA terms [22]. The time span over which a MACE or CV AE occurred in relation to drug exposure ranged from 22 weeks to 59 weeks across the six pooled analyses (Table 2).

Table 3.

Incidence of MACE in the integrated analyses of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists trialled in randomized controlled studies

| Reference, active intervention | No. of enrolled patients (D/C)a | MACE definition | No. of events (D/C) | Exposure-adjusted incidence rates per 100 patient-years (D/C) | Adjudicated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

White, 2013 [26] Alogliptin |

6028 (41,628/1860) | Composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke |

MACE, 13/10 CV death, 5/1 MI, 6/4 Stroke, 2/5 |

MACE, 0.64/1.04 CV death, 0.25/0.10 MI, 0.30/0.41 Stroke, 0.10/0.52 |

Yes |

|

Lehrke, 2014 [22] Linagliptin |

7400 (4810/2590) | CV AEs |

Cardiac disorder AEs, 153/83 ACS, 3/2 MI, 9/3 Narrow SMQ HF, 21/8 HF, 11/7 |

HF, 0.045/0.046 | No |

|

Rosenstock, 2015 [21] Linagliptin |

9459 (5847/3612) | Composite of CV death, nonfatal stroke, nonfatal MI, and hospitalization for UAP |

MACE, 60/62 CV death, 11/8 MI, 23/20 Stroke, 9/19 UAP, 22/16 |

MACE, 1.34/1.89 CV death, 0.24/0.24 MI, 0.51/0.61 Stroke, 0.2/0.58 UAP, 0.49/0.48 |

Yes |

|

Iqbal, 2014 [24] Saxagliptin |

9156 (5701/3455) | Composite of CV death, MI, stroke, and cardiac ischemic events (derived from post hoc and prospective adjudication of MedDRA preferred terms) |

MACE, 43/31 CV death, 17/15 MI, 19/12 Stroke, 16/10 |

MACE, 0.85/1.12 CV death, 0.34/0.54 MI, 0.40/0.45 Stroke, 0.27/0.36 |

Yes |

|

Engel, 2013 [23] Sitagliptin |

14,611 (7726/6885) | Composite of ischemic events reported as AEs with a MedDRA (version 14.1) term in a 39-item list and CV deaths reported as AEs with a MedDRA (version 14.1) term in an 11-item list |

MACE, 40/38 CV death, 12/10 |

MACE, 0.65/0.74 CV death, 0.25/0.25 |

No |

|

McInnes, 2015 [25] Vildagliptin 50 mg od and bd |

17,446 (9599/7847) | Composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke |

MACE, 83/85 CV death, 25/28 MI, 38/35 Stroke, 24/25 |

MACE, 0.90/1.16 CV death, 0.27/0.38 MI, 0.41/0.48 Stroke, 0.26/0.34 |

Yes |

|

Udell, 2015 [37] Alogliptin and saxagliptin |

21,872 (10,981/10,891) | None | HF, 395/317 | NR | Yes |

|

Abbas, 2016 [42] Alogliptin, saxagliptin, and sitagliptin |

36,543 (18,313/18,230) |

Composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke Secondary: hospitalization for HF |

MACE, 1663/1671 CV death, 671/664 MI, 737/745 Stroke, 333/332 HF, 602/536 |

NR | Yes |

|

Kundu, 2016 [39] Alogliptin, saxagliptin, and sitagliptin |

36,543 (18,313/18,230) |

Secondary: composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke Primary: hospitalization for HF |

MACE, 1663/1671 HF, 623/546 |

NR | Yes |

| Wang, 2016 [41] | Individual components of MACE: (1) all-cause death; (2) CV death; (3) nonfatal MI; (4) nonfatal stroke; (5) HF; (6) unstable angina; and (7) arrhythmia | NR | NR | No | |

|

Alogliptin Linagliptin Saxagliptin Sitagliptin Vildagliptin |

11,002 7987 23,073 30,558 6906 |

||||

|

Agarwal, 2014 [33] DPP-4 inhibitors |

73,678 (40,749/32,592) | Composite of CV death, MI, and strokeb | NR | NR | No |

|

Kongwatcharapong, 2016 [38] DPP-4 inhibitors |

74,737 (39,776/34,961) | Any occurrence of HF and HF-related hospitalizations | 726/635 | NR | No |

|

Li, 2016 [40] DPP-4 inhibitors |

28,292 (15,701/12,591) 37,028 (18,554/18,474) |

Co-primary: HF Co-primary: Hospital admission for HF |

42/33 622/522 |

NR | No |

|

Monami, 2013 [29] DPP-4 inhibitors |

40,071 (23,562/16,509) | Composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, stroke, ACS, and/or HF reported as serious AEs |

MACE, 263/232 CV death, 26/26 MI, 61/59 Stroke, 41/33 |

MACE, 1.12/1.37 CV death, 0.11/0.15 Acute MI, 0.26/0.35 Stroke, 0.17/0.19 |

No |

|

Monami, 2014 [34] DPP-4 inhibitors |

69,615 (29,788/22,776) | None | Acute HF, 448/361 | NR | No |

|

Patil, 2012 [30] DPP-4 inhibitors |

8544 (4998/3546) | Composite of death from CV causes, nonfatal MI or ACS, stroke, arrhythmias, and HF reported as AEs |

MACE, 45/56 ACS, 11/17 |

MACE, 0.14/0.14c ACS, 0.03/0.05c |

No |

|

Savarese, 2015 [36] DPP-4 inhibitors |

85,224 (48,486/36,738) | All-cause death, CV death, MI, stroke, and new onset of HF | NR | NR | No |

|

Wu, 2013 [31] DPP-4 inhibitors |

7778 | Composite of death from CV causes, nonfatal MI or ACS, stroke, arrhythmias, and heart failure reported as AEs | MACE, 6/18d; 10/12e | NR | No |

|

Wu, 2014 [35] DPP-4 inhibitors |

55,141 | None |

All-cause mortality, 627/601 CV death, 408/410 ACS, 621/610 Stroke, 222/219 HF, 424/352 |

NR | No |

|

Zhang, 2014 [32] DPP-4 inhibitors |

10,982 (5505/5477) | CV AEs | CE, 25/43f | NR | No |

|

Fisher, 2015 [53], Albiglutide |

5107 (2524/2583) |

Composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for UAP Secondary: MACE |

MACE or UAP, 58/58 MACE, 52/53 |

1.19/1.11 1.07/1.02 |

Yes |

|

Ferdinand, 2016 [54] Dulaglutide |

6010 (3885/2125) | Composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for UAP |

MACE, 26/25 CV death, 3/5 MI, 9/14 Stroke, 12/4 UAP, 3/6 |

MACE, 0.66/1.13 CV death, 0.08/0.23 MI, 0.23/0.63 Stroke, 0.31/0.18 UAP, 0.08/0.27 |

Yes |

|

Ratner, 2011 [51], Exenatide bd |

3945 (2316/1629) | Composite of CV death, MI, stroke, ACS, and revascularization procedures | MACE, 20/18 | 1.87/2.31 | Yes |

|

Marso, 2011 [50], Liraglutide |

6638 (4257/2381) | Composite of CV death, MI, and stroke reported as AEs using MedDRA terms | NR | NR | Yes |

|

Seshasai, 2015 [52] Taspoglutide |

7056 (4275/2781) | Composite of CV death, acute MI, stroke, and hospitalization for UAP | MACE, 40/27 |

CV death, 0.21/0.22 MI, 0.37/0.37 Stroke, 0.15/0.26 UAP, 0.1/0.15 All-cause mortality, 0.27/0.37 |

Yes |

|

Li, 2016 [56] GLP-1 receptor agonists |

11,758 (7441/4317) | HF | 17/19 | NR | No |

| Wang, 2016 [41] | Individual components of MACE: (1) all-cause death; (2) CV death; (3) nonfatal MI; (4) nonfatal stroke; (5) HF; (6) unstable angina; and (7) arrhythmia | NR | NR | No | |

|

Albiglutide Dulaglutide Exenatide Liraglutide Lixisenatide |

3286 2052 6283 4161 8607 |

||||

|

Monami, 2013 [12] GLP-1 receptor agonists |

15,398 (8619/6779) |

Composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, stroke, ACS, and/or HF reported as serious AEs |

NR | NR | No |

AEs adverse events, ACS acute coronary syndrome, bd twice daily, C comparator, CCV cardiovascular and cerebrovascular, CEC clinical events committee, D drug, HF heart failure, MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, MI myocardial infarction, NR not reported, od once daily, SMQ standardized Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities query, TIA transient ischemic attack, UAP unstable angina pectoris

aSome trials reported zero events and so the sum of the number of drug and comparator patients does not always equal the total number of enrolled patients

bSecondary outcome measure because of non-uniform reporting across the trials. The individual endpoints comprising MACE were the co-primary endpoints [33]

cMetric calculated by dividing the total number events in each group by total patient-years and multiplying by 100

dDPP-4 inhibitor monotherapy versus metformin monotherapy

eDPP-4 inhibitor plus metformin versus metformin monotherapy

fDPP-4 inhibitor monotherapy versus sulfonylurea therapy

MACE Incidence Rates

Variable definitions for MACE only allow exposure-adjusted incidence rates to be compared within and not between pooled analyses. Even so, Table 3 shows that exposure-adjusted incidence rates of MACE were lower with every DPP-4 inhibitor than with comparator regimens. Of the four pooled analyses that reported MACE as a robust endpoint [21, 24–26], exposure-adjusted incidence rates ranged from 0.64 to 1.34 events per 100 patient-years for DPP-4 inhibitors (alogliptin, saxagliptin, vildagliptin, and linagliptin) and from 1.04 to 1.89 events per 100 patient-years for the competitors, suggesting that treatment with DPP-4 inhibitors may reduce MACE in patients with T2DM. However, numbers of reported events remain too small for reliable statistical analysis. Exposure-adjusted incidence rate of MACE was highest in both arms of the linagliptin analysis conducted by Rosenstock et al. and it is noteworthy that, beyond MI, the additional term of hospitalization for UAP was a significant contributor to this metric (0.49 per 100 patient-years for linagliptin and 0.48 per 100 patient-years for all comparators) [21]. A high exposure-adjusted incidence rate of MACE was also noticeable in the vildagliptin 50 mg once and twice daily pooled analysis (0.90 per 100 patient-years for vildagliptin and 1.16 per 100 patient-years for all comparators), with nonfatal MI the largest single contributor (0.41 per 100 patient-years versus 0.48 per 100 patient-years, respectively) [25]. Exposure-adjusted CV death ranged from 0.24 to 0.34 per 100 patient-years for linagliptin [21], sitagliptin [23], alogliptin [26], saxagliptin [24], and vildagliptin [25].

MACE Risk

Across the various pooled analyses, none of the DPP-4 inhibitor treatments were associated with an increased risk for MACE relative to the respective control group (95% CI limits spanned unity; Fig. 2a). The upper 95% CI in the alogliptin pooled analysis breached the US FDA mandated threshold of 1.3, but findings from a subsequent randomized, placebo-controlled CV outcome trial demonstrated that the upper boundary of a one-sided repeated CI for a primary endpoint event was 1.16 (P < 0.001 for noninferiority, see below) [28]. Similar results to the base-case pooled analyses were obtained for linagliptin and sitagliptin when their data were reanalyzed using different statistical techniques [21, 23]. A time-to-event pooled analysis for linagliptin revealed that the incidence of the MACE increased over time as expected but at a similar rate as that observed in the placebo group [21]. Although theoretically possible that differences in MACE between DPP-4 inhibitors and controls are because of detrimental effects of the active comparators, rather than of a beneficial action of DPP-4 inhibitors, subgroup analyses revealed that the CV safety of linagliptin and sitagliptin compare favorably with placebo [21, 23]. In the comparison of linagliptin with placebo, the exposure-adjusted incidence rates for MACE were 1.49 and 1.64 per 100 patient-years, respectively, yielding an overall hazard ratio (HR) of 1.09 (95% CI 0.68–1.75) [21], while the corresponding rates for sitagliptin versus placebo were 0.80 and 0.76 per 100 patient-years, respectively (incidence rate ratio 1.01; 95% CI 0.55–1.86) [23].

Fig. 2.

Risk of a MACE: a pooled analyses of patient-level data for specific DPP-4 inhibitors, b meta-analyses of trial-level data for specific DPP-4 inhibitors, and c meta-analyses of trial-level data for DPP-4 inhibitors as a drug class. MACEs were defined differently in each analysis (see Table 2). CI confidence interval, DPP-4 dipeptidyl peptidase-4, HR hazard ratio, OR odds ratio, RR risk ratio. aVildagliptin 50 mg once daily and twice daily. bAll included studies. The principal analysis excluded seven studies that did not report events. cUpper 95% CI not shown. dDPP-4 inhibitor monotherapy versus metformin monotherapy. eDPP-4 inhibitor plus metformin versus metformin monotherapy. fDPP-4 inhibitors versus sulfonylureas

Subgroup analyses further showed that the magnitude of the adjudicated MACE risk associated with linagliptin and vildagliptin 50 mg once and twice daily versus total comparators was not affected by age, sex, or high CV disease risk status [21, 25]. Race, use of rescue therapy, occurrence of hypoglycemia, renal function, microalbuminuria, or use of background medication (insulin and/or metformin) were also factors deemed not to impact the magnitude of adjudicated MACE risk associated with linagliptin versus total comparators [21]. Subgroup analyses of adjudicated MACE for saxagliptin suggested that the 2.5 mg daily dosage regimen (incidence rate ratio 0.33; 95% CI 0.10–0.89) but not the 5 mg daily dosage regimen (incidence rate ratio 0.74; 95% CI 0.40–1.36) had a lower MACE risk relative to all comparators [24]. Any saxagliptin dosage adjunctive to metformin was not associated with increased risk for MACE relative to control (incidence rate ratio 0.93; 95% CI 0.44–1.99) [24]. Limited data from three studies showed that sitagliptin was associated with a lower incidence and risk of MACE than a sulfonylurea (exposure-adjusted incidence rate 0.00 per 100 patient-years with sitagliptin versus 0.86 with sulfonylurea: incidence rate ratio 0.00; 95% CI 0.00–0.31) [23].

MACE Components

Although risks for individual components of the composite MACE endpoints were not consistently reported across the pooled analyses, it was apparent that the risks for individual CV components were not increased with linagliptin, saxagliptin, or vildagliptin versus total comparators [21, 24, 25], and that the risk for CV-related death was not heightened by sitagliptin relative to control (Table 4) [23]. There was some evidence suggesting that linagliptin was associated with a reduced risk for stroke (incidence rate ratio 0.34; 95% CI 0.15–0.75) but this observation is based on a low number of events, with many trials having no events in one or both treatment groups. The same caveat applies to the observation that linagliptin may reduce risk for transient ischemic attacks (Table 4).

Table 4.

Risk ratios (95% CIs) for individual MACE reported in integrated analyses of DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists

| First author [reference] | Drug | CV event category | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV death | MI | Stroke | ACS | Arrhythmia | TIA | Heart failure | All death | UAP | ||

| White, 2013 [26] | Alogliptin | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Iqbal, 2014 [24]a | Saxagliptin | 0.61 (>1) | 0.87 (>1) | 0.75 (>1) | NR | NR | NR | 0.55 (>1) | NR | NR |

| Engel, 2013 [23] | Sitagliptin | 0.95 (0.40–2.30) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Rosenstock, 2015 [21] | Linagliptin | 1.04 (0.42–2.60) | 0.86 (0.47–1.56) | 0.34 (0.15–0.75) | NR | NR | 0.09 (0.01–0.75) | NR | 0.89 (0.45–1.75) | 1.08 (0.56–2.06)b |

| McInnes, 2015 [25] | Vildagliptin 50 mg od and bd | 0.77 (0.45–1.31) | 0.97 (0.56–1.38) | 0.84 (0.47–1.50) | NR | NR | NR | 1.08 (0.68–1.70) | NR | NR |

| Wang, 2016 [41] | Alogliptin | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) | 1.06 (0.86–1.31) | 0.86 (0.54–1.36) | NR | 1.25 (0.44–3.52) | NR | 1.22 (0.92–1.60) | 0.86 (0.69–1.07) | 0.86 (0.58–1.28) |

| Linagliptin | 1.85 (0.56–6.08) | 0.90 (0.45–1.78) | 0.49 (0.24–1.00) | NR | 1.47 (0.64–3.42) | NR | 1.87 (0.84–4.15) | 0.94 (0.38–2.33) | 1.58 (0.52–4.76) | |

| Saxagliptin | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | 0.93 (0.79–1.10) | 1.12 (0.90–1.40) | NR | 1.14 (0.47–2.78) | NR | 1.23 (1.03–1.46) | 1.09 (0.95–1.26) | 1.18 (0.88–1.58) | |

| Sitagliptin | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | 0.98 (0.83–1.15) | 0.91 (0.73–1.13) | NR | 1.14 (0.54–2.41) | NR | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) | 1.00 (0.89–1.13) | 0.86 (0.68–1.10) | |

| Vildagliptin | 2.19 (0.53–9.01) | 0.20 (0.04–1.00) | 0.26 (0.08–0.84) | NR | 0.91 (0.34–2.45) | NR | 0.80 (0.16–4.09) | 0.95 (0.35–2.60) | NR | |

| Udell, 2015 [37] | Alogliptin and saxagliptin | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1.25 (1.08–1.45) | NR | NR |

| Abbas, 2016 [42] | Alogliptin, saxagliptin, and sitagliptin | 1.01 (0.91–1.12) | 0.99 (0.89–1.09) | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) | NR | NR | NR | 1.12 (1.00–1.25) | NR | NR |

| Kundu, 2016 [39] | Alogliptin, saxagliptin, and sitagliptin | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1.14 (0.97–1.34)b | NR | NR |

| Agarwal, 2014 [33] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 0.95 (0.82–1.09) | 0.98 (0.86–1.10) | 0.92 (0.77–1.11) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1.00 (0.90–1.13) | NR |

| Kongwatcharapong, 2016 [38] | DPP-4 inhibitors | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1.106 (0.995–1.228) | NR | NR |

| Li, 2016 [40] | DPP-4 inhibitors | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

0.97 (0.61–1.56) 1.13 (1.00–1.26)b |

NR | NR |

| Monami, 2013 [29] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 0.67 (0.39–1.14) | 0.64 (0.44–0.94)c | 0.77 (0.48–1.24) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.60 (0.41–0.88) | NR |

| Monami, 2014 [34] | DPP-4 inhibitors | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1.19 (1.03–1.30)d | NR | NR |

| Patil, 2012 [30] | DPP-4 inhibitors | NR | NR | NR | 0.40 (0.18–0.88)e | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Savarese, 2015 [36] | DPP-4 inhibitors (STFU) | 1.03 (0.51–2.07) | 0.58 (0.36–0.94)f | 0.66 (0.36–1.21) | NR | NR | NR | 0.67 (0.32–1.40) | 1.064 (0.56–2.00) | NR |

| DPP-4 inhibitors (LTFU) | 0.962 (0.84–1.10) | 0.94 (0.84–1.06) | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | NR | NR | NR | 1.16 (1.01–1.33)g | 1.01 (0.91–1.13) | NR | |

| Wu, 2013 [31] | DPP-4 inhibitors | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Wu, 2014 [35] | DPP-4 inhibitors | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) | NR | 0.98 (0.81–1.18) | 0.97 (0.87–1.08) | NR | NR | 1.16 (1.01–1.33)h | 1.01 (0.91–1.13) | NR |

| Zhang, 2014 [32] | DPP-4 inhibitors | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Fisher, 2015 [53] | Albiglutide | 1.06 (0.55–2.06) | 0.96 (0.52–1.76) | 1.02 (0.45–2.33) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.77 (0.25–2.37)b |

| Ferdinand, 2016 [54] | Dulaglutide | 0.35 (0.07–1.87)i | 0.35 (0.13–0.95)i | 1.61 (0.42–6.20)i | NR | NR | NR | 2.02 (0.41–9.88)b, i | 0.50 (0.18– 1.38)i | 0.28 (0.05–1.46)b, i |

| Ratner, 2011 [51] | Exenatide bd | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Marso, 2011 [50] | Liraglutide | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Seshasai, 2015 [52] | Taspoglutide | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.89 (0.38–2.07) | NR |

| Wang, 2016 [41] | Albiglutide | NR | 1.20 (0.57–2.51) | 0.57 (0.19–1.69) | NR | 2.01 (0.70–5.73) | NR | 0.45 (0.17–1.17) | 0.56 (0.12–2.59) | 0.87 (0.32–2.38) |

| Dulaglutide | NR | 0.21 (0.04–0.98) | 2.83 (0.60–13.28) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Exenatide | 1.68 (0.28–9.87) | 0.81 (0.29–2.25) | 1.56 (0.45–5.41) | NR | 2.83 (1.06–7.57) | NR | 1.92 (0.39–9.50) | 1.17 (0.47–2.89) | 0.83 (0.22–3.08) | |

| Liraglutide | NR | 1.03 (0.43–2.47) | 1.06 (0.33–3.37) | NR | 0.74 (0.20–2.77) | NR | 5.52 (0.90–33.95) | 0.47 (0.02–8.88) | NR | |

| Lixisenatide | 0.98 (0.78–1.23) | NR | 2.74 (0.38–19.50) | NR | 4.50 (0.24–84.78) | NR | NR | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | NR | |

| Li, 2016 [56] | GLP-1 receptor agonists | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.62 (0.31–1.22) | NR | NR |

| Monami, 2013 [12] | GLP-1 receptor agonists | 0.63 (0.24–1.66) | 0.87 (0.48–1.56) | 0.87 (0.37–2.05) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.89 (0.46–1.70) | NR |

ACS acute coronary syndrome, bd twice daily, CV cardiovascular, LTFU long-term follow-up (>29 weeks), MI myocardial infarction, od once daily, NR not reported, STFU short-term follow-up (<29 weeks), TIA transient ischemic attack, UAP unstable angina pectoris

a95% Confidence intervals not reported but included one based on visual inspection of graph [24]

bRequiring hospitalization

c P = 0.023 DPP-4 inhibitors versus placebo/active comparators

d P = 0.015 DPP-4 inhibitors versus placebo/active comparators

eTerm included nonfatal MI

f P = 0.028 DPP-4 inhibitors versus placebo/active comparators

g P = 0.034 DPP-4 inhibitors versus placebo/active comparators

h P = 0.04 DPP-4 inhibitors versus placebo/active comparators

iAdjusted 98.02% CI

One of the two linagliptin pooled analyses assessed hospitalization for adjudicated congestive HF (CHF) (from eight trials including 3314 subjects) as well as investigator-reported AEs suggestive of CHF (from 24 placebo-controlled trials including 8778 subjects) [21]. Occurrence of hospitalization for CHF was low for linagliptin (12 events, 2039 patients) and the total comparator group (nine events, 1275 patients) yielding an HR of 1.04 (95% CI 0.43–2.47). Occurrence of investigator-reported AEs suggestive of CHF was also low for linagliptin-treated patients (26 events, 0.5%; 16 serious events, 0.3%) and comparable with that in placebo-treated patients (eight events, 0.2%; six serious events, 0.2%) [21]. In the other linagliptin pooled analysis, rates of HF AEs based on the preferred terms cardiac failure, cardiac failure acute, and cardiac failure congestive were similar among linagliptin- and placebo-treated patients (0.2% and 0.3%, respectively), equating to an incidence rate per 100 patient-years of 0.045 for linagliptin and 0.046 for placebo (Table 3) [22]. The large vildagliptin pooled analysis indicated that this agent is not associated with an increased risk of HF defined as new onset or hospitalization for worsening HF (RR 1.08; 95% CI 0.68–1.70; Table 4) [25].

Meta-analyses

Features

Of 20 articles identified from our literature search on gliptins that met eligibility criteria, 14 were meta-analyses (Table 2) [29–42]. Ten reported on the CV safety of DPP-4 inhibitors as a drug class [29–36, 38, 40], seven reported on the CV safety of individual DPP-4 inhibitors [29, 30, 33, 34, 36, 38, 41], and three reported on CV outcomes with alogliptin, sitagliptin and saxagliptin or alogliptin and saxagliptin combined [37, 39, 42] based on data pooled from phase 4 studies—EXAMINE [28], SAVOR–TIMI 53 [43], and TECOS [44]. Similar robust definitions of MACE were applied in four of the meta-analyses [29–31, 33], and a fifth utilized an unclear definition of CV events rather than MACE per se [32] (Table 3). Eight meta-analyses focused on individual MACEs as co-primary endpoints as opposed to a composite MACE endpoint [33–36, 38–41].

Of the two meta-analyses that described overall CV safety of individual DPP-4 inhibitors as a primary endpoint [29, 30], one was restricted to monotherapy studies of 18 trials [30], whereas the other was extended to studies in which DPP-4 inhibitors were administered in association with other glucose-lowering agents, provided that concurrent therapies were the same in all treatment groups [29]. All of the studies included in the monotherapy analysis [30] were also included in the larger analysis of all available studies [29].

MACE Risk

The larger of the two meta-analyses assessing overall CV safety of individual DPP-4 inhibitors included 70 trials: nine trials of linagliptin, 13 trials of saxagliptin, 27 trials of sitagliptin, 16 trials of vildagliptin, and five trials of alogliptin [29]. Sixty-three of these 70 trials reported MACE, and enrolled a total of 40,071 patients, including 23,562 assigned to treatment with one of the five DPP-4 inhibitors and 16,509 assigned to control treatment [29]. With a total of 263 MACE attributed to DPP-4 inhibitors, the exposure-adjusted incidence rate of 1.12 events per 100 patient-years was not dissimilar to that of the patient-level data in the aforementioned pooled analyses (Table 3). Overall, the results of this meta-analysis were in agreement with the pooled analyses in that no DPP-4 inhibitor was associated with a statistically significant increased risk for MACE as their 95% CIs crossed unity (Fig. 2b) [29]. More specifically, there was a general trend of the base-case point estimates towards a MACE risk reduction in patients assigned to any of the five DPP-4 inhibitors relative to control, although these reductions only reached statistical significance with saxagliptin and vildagliptin (Fig. 2b) [29]. Corresponding findings from the smaller meta-analysis of DPP-4 inhibitor monotherapy studies were similar in that there was no suggestion of statistically significant increased risk for MACE with DPP-4 inhibitors but a statistically significantly reduced MACE risk was detected with sitagliptin (Fig. 2b) [30]; however, the latter finding has subsequently been refuted by the TECOS randomized, placebo-controlled study, which demonstrated that sitagliptin neither increased nor decreased MACE risk (see below) [44].

A third meta-analysis tested the association between individual DPP-4 inhibitors and risk for the composite MACE endpoint as a secondary objective [33]. By including EXAMINE and SAVOR–TIMI 53 [28, 43] this meta-analysis was unevenly weighted since these phase 4 trials were characterized by very large sample sizes and prolonged follow-up relative to the other phase 2/3 trials included in the analysis [33]. Furthermore, the clinical characteristics of the patients who participated in EXAMINE and SAVOR–TIMI 53 were considerably different from the populations of the other included trials (i.e., patients were at higher risk for MACE) [28, 43]. Even so, no statistically significant increased risk for MACE was detected with any DPP-4 inhibitor in this meta-analysis (Fig. 2b), and the available data suggested that linagliptin could be associated with a reduced risk for MACE [33].

Two meta-analyses suggested a significant reduction in the incidence of MACE associated with DPP-4 inhibitor therapy as a drug class, with an estimated odds ratio (OR) of 0.48 (95% CI 0.31–0.75) for the meta-analysis of monotherapy studies [30] and 0.71 (95% CI 0.59–0.86) for the larger meta-analysis of all available studies (Fig. 2c) [29]. However, in the meta-analysis conducted by Agarwal et al. this statistical advantage in favor of DPP-4 inhibitor therapy was annulled when EXAMINE and SAVOR–TIMI 53 data were included (OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.86–1.04) [33]. No change in effect size was observed when the ORs were recalculated using a continuity correction to avoid distortions because of the exclusion of trials with zero events [29, 30], or by use of a random effects model instead of a fixed effects model [33]. Subgroup analysis of the meta-analysis of monotherapy studies revealed that studies with a duration of at least 52 weeks demonstrated a lower risk for MACE with DPP-4 inhibitor therapy than control (RR 0.37; 95% CI 0.21–0.63; P = 0.0003), which was not the case in shorter-term studies (RR 0.78; 95% CI 0.38–1.60; P = 0.50) [30]. Meta-regression revealed no influence of sex, diabetes duration, or HbA1c level upon the pooled OR for MACE in the meta-analysis by Agarwal et al. [33].

In the larger meta-analysis performed by Monami et al., risk of MACE with DPP-4 inhibitor therapy was 28% lower when compared with placebo based on 38 studies with at least one event (OR 0.72; 95% CI 0.56–0.92; P = 0.01) [29]. However, in the meta-analysis restricted to monotherapy studies, no such reduction in MACE risk was observed for DPP-4 inhibitor therapy versus placebo (RR 1.05; 95% CI 0.39–2.82; P = 0.92) but there appeared to be a significantly lower risk relative to metformin (RR 0.42; 95% CI 0.20–0.87; P = 0.02) and other oral hypoglycemic agents, including sulfonylureas and thiazolidinediones (RR 0.33; 95% CI 0.16–0.67; P = 0.002) [30]. A lower CV safety risk with DPP-4 inhibitor therapy versus active comparators was also observed in two other meta-analyses (Fig. 2c) [31, 32]. One meta-analysis indicated that DPP-4 inhibitor monotherapy was associated with less risk for MACE than metformin monotherapy (RR 0.36; 95% CI 0.15–0.85; P = 0.02), but that this safety advantage was lost when metformin was added to the DPP-4 inhibitor regimen as initial combination therapy (RR 0.54; 95% CI 0.25–1.19; P = 0.13) [31]. The other meta-analysis, which used a less robust MACE definition, suggested that CV events were less likely with DPP-4 inhibitor therapy than with sulfonylurea therapy (OR 0.53; 95% CI 0.32–0.87) but that patients receiving DPP-4 inhibitor therapy were also slightly less likely to attain HbA1c below 7% (OR 0.91; 95% CI 0.84–0.99) [32].

Fixed and random effects meta-analyses of three phase 4 prospective CV outcome studies found no evidence for an increased risk of MACE associated with alogliptin, saxagliptin, and sitagliptin as a class versus placebo in high-risk patients with T2DM (fixed and random effects model: RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.93–1.06 [42]; random effects model: OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.92–1.06 [39]). However, the scientific validity of pooling clinical trial data from distinct CV risk populations must be taken into consideration when interpreting these results.

Twelve of the 14 meta-analyses reported individual DPP-4 inhibitor data and DPP-4 inhibitor data as a drug class on the components of MACE composite endpoints [29, 30, 33–42]. In general, there was no class effect on the risk for the three most commonly used MACE components (CV death, MI, and stroke), as well as for other MACE components (Table 4). The drug class was associated with lower risk for MI in two meta-analyses [29, 36], although this association was lost over the long term (i.e., more than 29 weeks’ treatment) in the meta-analysis that included EXAMINE and SAVOR-TIMI 53 data (see below) [36]. Ninety-five percent CIs of pooled ORs/RRs for death, CV death, MI, and stroke included the value 1 when the data were stratified by individual DPP-4 inhibitor therapy, with the exception of stroke risk with linagliptin (OR 0.45; 95% CI 0.23–0.89 [33]; RR 0.29; 95% CI 0.13–0.65; P = 0.003 [36]) and vildagliptin (OR 0.23; 95% CI 0.07–0.71 [33]; RR 0.30; 95% CI 0.10–0.92; P = 0.035 [36]; and OR 0.26; 95% CI 0.08–0.84 [41]). Vildagliptin was also associated with significant reduction in the risk of MI (RR 0.35; 95% CI 0.17–0.72; P = 0.004) [36]. There was a higher risk for HF associated with DPP-4 inhibitors as a drug class in a meta-analysis that focused on this outcome as a primary endpoint [34], as well as a 16% increased HF risk in two other meta-analyses that included EXAMINE (alogliptin) and SAVOR-TIMI 53 (saxagliptin) data [35, 36]. A meta-analysis of EXAMINE and SAVOR–TIMI 53 data exclusively indicated that DPP-4 inhibitor therapy with either alogliptin or saxagliptin was associated with a 25% increased risk for HF relative to standard care with glucose or weight management (RR 1.25; 95% CI 1.08–1.45; P = 0.0033) [37], although this risk became nonsignificant in four other meta-analyses also featuring TECOS data (sitagliptin versus placebo) (RR 1.12; 95% CI 1.00–1.25 [42]; OR 1.14; 95% CI 0.97–1.34 [39]; RR 1.116; 95% CI 0.995–1.228 [38]; OR 0.97; 95% CI 0.61–1.56 [40]; Table 4). When analyzed individually, only saxagliptin was associated with increased risk for HF (RR 1.215; 95% CI 1.028–1.437; P = 0.022 [38]; OR 1.23; 95% CI 1.03–1.56 [41]), which is likely driven by an increased risk in patients at high CV risk (RR 1.257; 95% CI 1.060–1.491; P = 0.009) rather than low CV risk (RR 0.537; 95% CI 0.232–1.245; P = 0.148) [38].

Randomized Controlled Trial Data

We identified one primary article and one secondary article for the Examination of Cardiovascular Outcomes with Alogliptin versus Standard of Care (EXAMINE) trial [28, 45], one primary article and two secondary articles for the Saxagliptin Assessment of Vascular Outcomes Recorded in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus (SAVOR)–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 53 (SAVOR-TIMI 53) trial [43, 46, 47], and one primary article for the Trial to Evaluate Cardiovascular Outcomes after Treatment with Sitagliptin (TECOS) [44]. Overall, EXAMINE, SAVOR-TIMI 53, and TECOS found no evidence that DPP-4 inhibitor therapy alters MACE risk relative to placebo [28, 43, 44, 48].

EXAMINE was a double-blind, noninferiority trial, wherein alogliptin as an adjunct to standard care was compared with standard care alone in 5380 patients with T2DM comorbid with ACS [28]. Doses of alogliptin were adjusted according to kidney function at the time of randomization and when needed during the trial on the basis of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculated with the use of the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula. Inclusion criterion for T2DM at screening was an HbA1c level of 6.5–11.0% despite treatment with antidiabetic therapy other than a DPP-4 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist. ACS must have occurred within 15–90 days prior to randomization, and was defined as acute MI and unstable angina requiring hospitalization [49]. The primary outcome was time from randomization to occurrence of a MACE, which was defined as a composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke. Baseline mean HbA1c level was 8.0% in both groups. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups for the primary endpoint (HR 0.96; 95% CI ≤1.16%, P = 0.32; P < 0.001 for noninferiority), for components of the primary endpoint, and for all prespecified secondary and exploratory endpoints, including hospital admission for HF (Table 5) [28, 45]. Post-hoc analysis of EXAMINE indicated that risk of CV death and hospital admission for HF was similar for alogliptin and placebo, both in the entire study population (HR 1.00; 0.82–1.21) and in those with a history of HF at baseline (HR 0.90; 0.70–1.17) [45].

Table 5.

Prespecified MACE and events related to other CV endpoints reported in the Examination of Cardiovascular Outcomes with Alogliptin versus Standard of Care (EXAMINE) trial [28, 45], the Saxagliptin Assessment of Vascular Outcomes Recorded in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus (SAVOR)–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 53 trial [43], the Trial to Evaluate Cardiovascular Outcomes after Treatment with Sitagliptin (TECOS) [44], the Evaluation of Lixisenatide in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ELIXA) trial [48], and the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results (LEADER) trial [55]

| Patients with T2DM who had had a recent ACS [28, 45] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Alogliptin (N = 2701) | Placebo (N = 2679) | HR for DPP-4 inhibitor (95% CI) | P value |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Composite primary MACE endpoint: CV death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke | 305 (11.3) | 316 (11.8) | 0.96 (≤1.16) | 0.32 |

| CV death | 89 (3.3) | 111 (4.1) | 0.79 (0.60–1.04) | 0.10 |

| Nonfatal MI | 187 (6.9) | 173 (6.5) | 1.08 (0.88–1.33) | 0.47 |

| Nonfatal stroke | 29 (1.1) | 32 (1.2) | 0.91 (0.55–1.50) | 0.71 |

| Secondary composite MACE endpoint: CV causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or urgent revascularization because of UAP < 24 h after hospital admission | 344 (12.7) | 359 (13.4) | 0.95 (≤1.14) | 0.26 |

| Prespecified exploratory endpoint and first occurrence of components | ||||

| Composite | 433 (16.0) | 441 (16.5) | 0.98 (0.86–1.12) | 0.73 |

| All-cause mortality | 106 (3.9) | 131 (4.9) | 0.80 (0.62–1.03) | 0.08 |

| Nonfatal MI | 171 (6.3) | 155 (5.8) | 1.10 (0.88–1.37) | 0.39 |

| Nonfatal stroke | 28 (1.0) | 29 (1.1) | 0.97 (0.58–1.62) | 0.90 |

| Urgent revascularization because of UAP | 43 (1.6) | 47 (1.8) | 0.90 (0.60–1.37) | 0.63 |

| Hospital admission for HF | 85 (3.1) | 79 (2.9) | 1.07 (0.79–1.46) | 0.66 |

| SAVOR-TIMI 53: Patients with T2DM who had established CV disease or multiple risk factors for vascular disease [43] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Saxagliptin (N = 8280) | Placebo (N = 8212) | HR for DPP-4 inhibitor (95% CI) | P value |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Composite primary MACE endpoint: CV death, MI, or stroke | 613 (7.3) | 609 (7.2) | 1.00 (0.89–1.12) | 0.99 |

| Primary secondary endpoint: primary composite endpoint plus hospitalization for HF, coronary revascularization or UAP | 1059 (12.8) | 1034 (12.4) | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 0.66 |

| Death from any cause | 420 (4.9) | 378 (4.2) | 1.11 (0.96–1.27) | 0.15 |

| CV death | 269 (3.2) | 260 (2.9) | 1.03 (0.87–1.22) | 0.72 |

| MI | 265 (3.2) | 278 (3.4) | 0.95 (0.80–1.12) | 0.52 |

| Ischemic stroke | 157 (1.9) | 141 (1.7) | 1.11 (0.88–1.39) | 0.38 |

| Hospitalization for UAP | 97 (1.2) | 81 (1.0) | 1.19 (0.89–1.60) | 0.24 |

| Hospitalization for HF | 289 (3.5) | 228 (2.8) | 1.27 (1.07–1.51) | 0.007 |

| Hospitalization for coronary revascularization | 423 (5.2) | 459 (5.6) | 0.91 (0.80–1.04) | 0.18 |

| Doubling of creatinine level, initiation of dialysis, renal transplantation, or creatinine >6.0 mg/dL (530 μmol/L) | 194 (2.2) | 178 (2.0) | 1.08 (0.88–1.32) | 0.46 |

| TECOS: Patients with T2DM and established CV disease [44] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Sitagliptin (N = 7257) | Placebo (N = 7266) | HR for DPP-4 inhibitor (95% CI) | P value |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Composite primary MACE endpoint:a CV death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for UAP | 695 (9.6) | 695 (9.6) | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) | <0.001 |

| Composite secondary MACE endpoint:a CV death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke | 609 (8.4) | 602 (8.3) | 0.99 (0.89–1.11) | <0.001 |

| CV deathb | 380 (5.2) | 366 (5.0) | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | 0.71 |

| Hospitalization for UAPb | 116 (1.6) | 129 (1.8) | 0.90 (0.70–1.16) | 0.42 |

| Fatal or nonfatal MIb | 300 (4.1) | 316 (4.3) | 0.95 (0.81–1.11) | 0.49 |

| Fatal or nonfatal strokeb | 178 (2.4) | 183 (2.5) | 0.97 (0.79–1.19) | 0.76 |

| Death from any causeb | 547 (7.5) | 537 (7.3) | 1.01 (0.90–1.14) | 0.88 |

| Hospitalization for HFb | 228 (3.1) | 229 (3.1) | 1.00 (0.83–1.20) | 0.98 |

| Hospitalization for HF or CV deathb | 538 (7.3) | 525 (7.2) | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | 0.74 |

| ELIXA: Patients with T2DM who had had a recent ACS [48] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Lixisenatide (N = 3034) | Placebo (N = 3034) | HR for GLP-1 RA (95% CI) | P value |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Composite primary MACE endpoint: CV death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for UAP | 399 (13.2) | 406 (13.4) | 1.02 (0.89–1.17) | 0.81 |

| CV death | 93 (3.1) | 88 (2.9) | ||

| Nonfatal MI | 247 (8.1) | 255 (8.4) | ||

| Nonfatal stroke | 49 (1.6) | 54 (1.8) | ||

| UAP | 10 (0.3) | 9 (0.3) | ||

| Primary endpoint event or hospitalization for HF | 469 (15.5) | 456 (15.0) | 0.97 (0.85–1.10) | 0.63 |

| Primary endpoint event, hospitalization for HF, or revascularization | 659 (21.7) | 661 (21.8) | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 0.96 |

| Hospitalization for HF | 127 (4.2) | 122 (4.0) | 0.96 (0.75–1.23) | 0.75 |

| Death from any cause | 223 (7.4) | 211 (7.0) | 0.94 (0.78–1.13) | 0.50 |

| LEADER: Patients with T2DM who were at high risk for CV events [57] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endpoint | Liraglutide (N = 4668) | Placebo (N = 4672) | HR for GLP-1 RA (95% CI) | P value |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Primary composite outcome: death from CV causes, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke | 608 (13.0) | 694 (14.9) | 0.87 (0.78–0.97) | 0.01 |

| Expanded composite outcome: death from CV causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or hospitalization for UAP or HF | 948 (20.3) | 1062 (22.7) | 0.88 (0.81–0.96) | 0.005 |

| Death from any cause | 381 (8.2) | 447 (9.6) | 0.85 (0.74–0.97) | 0.02 |

| Death from CV causes | 219 (4.7) | 278 (6.0) | 0.78 (0.66–0.93) | 0.007 |

| Death from non-CV causes | 162 (3.5) | 169 (3.6) | 0.95 (0.77–1.18) | 0.66 |

| MI | 292 (6.3) | 339 (7.3) | 0.86 (0.73–1.00) | 0.046 |

| Fatal | 17 (0.4) | 28 (0.6) | 0.60 (0.33–1.10) | 0.10 |

| Nonfatal | 281 (6.0) | 317 (6.8) | 0.88 (0.75–1.03) | 0.11 |

| Silent | 62 (1.3) | 76 (1.6) | 0.86 (0.61–1.20) | 0.37 |

| Stroke | 173 (3.7) | 199 (4.3) | 0.86 (0.71–1.06) | 0.16 |

| Fatal | 16 (0.3) | 25 (0.5) | 0.64 (0.34–1.19) | 0.16 |

| Nonfatal | 159 (3.4) | 177 (3.8) | 0.89 (0.72–1.11) | 0.30 |

| TIA | 48 (1.0) | 60 (1.3) | 0.79 (0.54–1.16) | 0.23 |

| Coronary revascularization | 405 (8.7) | 441 (9.4) | 0.91 (0.80–1.04) | 0.18 |

| Hospitalization for UAP | 122 (2.6) | 124 (2.7) | 0.98 (0.76–1.26) | 0.87 |

| Hospitalization for HF | 218 (4.7) | 248 (5.3) | 0.87 (0.73–1.05) | 0.14 |

| Microvascular event | 355 (7.6) | 416 (8.9) | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | 0.02 |

| Retinopathy | 106 (2.3) | 92 (2.0) | 1.15 (0.87–1.52) | 0.33 |

| Nephropathy | 268 (5.7) | 337 (7.2) | 0.78 (0.67–0.92) | 0.003 |

CV cardiovascular, DPP-4 dipeptidyl peptidase-4, GLP-1 RA glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, HF heart failure, HR hazard ratio, MI myocardial infarction, TIA transient ischemic attack, UAP unstable angina pectoris

aPer-protocol analysis

bIntention-to-treat analysis

SAVOR-TIMI 53 compared renally adjusted saxagliptin with placebo when added to current therapy in 16,492 patients with established T2DM (baseline mean HbA1c level, 8.0%) who had a history of, or who were at risk for, CV events [43]. Patients with documented CV disease were at least 40 years of age, and had a history of a clinical event associated with atherosclerosis involving the coronary, cerebrovascular, or peripheral vascular system. Patients with multiple risk factors for CV events were at least 55 years old (men) or 60 years old (women) with at least one of the following additional risk factors: dyslipidemia, hypertension, or active smoking. The primary outcome was time to first MACE, defined as a composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal ischemic stroke. Patients were followed for a median of 2.1 years, during which time their antidiabetic medications and other medications could be adjusted at the discretion of their attending physician. As in EXAMINE, the SAVOR-TIMI 53 data revealed no statistically significant difference between the groups regarding the primary endpoint: 7.3% of patients in the saxagliptin arm and 7.2% of patients in the placebo arm experienced a MACE (HR 1.00; 95% CI 0.89–1.12, P = 0.99; P < 0.001 for noninferiority) (Table 5). However, unlike therapy with alogliptin in EXAMINE, therapy with saxagliptin increased the relative risk of hospitalization for HF (3.5% versus 2.8%; HR 1.27; 95% CI 1.07–1.51; P = 0.007) corresponding to a 0.7% absolute risk over 2 years [43]. Incidence of hospitalization for HF was also higher in the saxagliptin than placebo group at 12 months (1.9% versus 1.3%; HR 1.46; 95% CI 1.15–1.88; P = 0.002) [46]. Multivariable analyses revealed that subjects at greatest risk of hospitalization for HF had previous HF (adjusted HR 4.18; 95% CI 3.48–5.02), an eGFR ≤60 mL/min (adjusted HR 2.00; 95% CI 1.65–2.42), or elevated baseline levels (quartile 4) of N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (adjusted HR 5.51; 95% CI 4.24–7.16) [46]. Risk of MACE in SAVOR-TIMI 53 was similar among elderly (≥65 years, HR 0.92; 95% CI 0.79–1.06; <65 years, HR 1.15; 95% CI 0.96–1.37; interaction P value 0.06) and very elderly (≥75 years, HR 0.95; 95% CI 0.75–1.22; <75 years, HR 1.01; 95% CI 0.89–1.15; interaction P value 0.67) patients who received saxagliptin and placebo [47]. The increased risk of HF-associated hospitalization with saxagliptin relative to placebo was similar regardless of age group [47].

TECOS was a randomized, double-blind trial that assigned 14,671 T2DM patients (baseline mean HbA1c level, 7.2%) to either sitagliptin 100 mg daily (or 50 mg daily if baseline eGFR was ≥30 and <50 mL/min/1.73 m2 of body surface area) (n = 7257) or placebo (n = 7266) in addition to their existing therapy (one or two oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin with or without metformin) [44]. Open-label use of antihyperglycemic therapy was encouraged as required for the attainment of appropriate glycemic targets. Eligible patients were at least 50 years of age and had established CV disease defined as a history of major coronary artery disease, ischemic cerebrovascular disease, or atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease. In TECOS, MACE was defined as the composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina. During a median follow-up of 3.0 years (interquartile range 2.3–3.8 years), sitagliptin was noninferior to placebo with respect to MACE (HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.88–1.09; P < 0.001), and there was no statistically significant between-group difference regarding rates of hospitalization for HF (HR 1.00; 95% CI 0.83–1.20; P = 0.98) (Table 5) [44].

CV Risk of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists

Pooled Analyses

Features

Of nine articles on GLP-1 receptor agonists identified from our literature search, five were drug-specific pooled analyses—one each for liraglutide [50], exenatide twice daily [51], taspoglutide [52], albiglutide [53], and dulaglutide [54] (Table 2). Excluding taspoglutide (since development has been suspended), the sample size was largest for the pooled analysis of liraglutide CV safety (n = 6638) and smallest for that of exenatide (n = 3945) (Table 3). These analyses assessed CV safety of the drugs with or without background therapy. CV safety was compared with all active interventions combined for liraglutide [50], with placebo and insulin combined for exenatide [51], and with placebo and active comparators combined for albiglutide [53] and dulaglutide [54]. The authors of the exenatide study acknowledge that pooling the placebo group with a single active-comparator group was a necessary limitation to provide greater statistical power [51]. Adjudicated MACEs were evaluated on a post hoc basis in the liraglutide and exenatide analyses but were prespecified in the albiglutide and dulaglutide analyses [50, 51, 53, 54]. The MACE definitions were broadly similar except that the exenatide pooled analysis included ACS and revascularization procedures in addition to CV death, stroke, and MI [51]. Technically, time to first MACE was a secondary endpoint in the albiglutide pooled analysis, as the primary endpoint was time to first MACE or hospital admission for UAP [53].

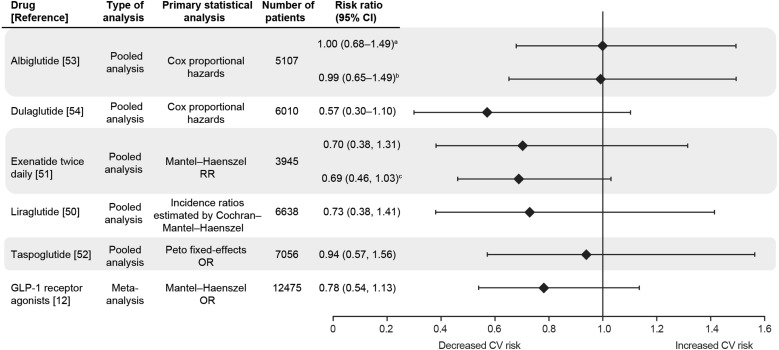

MACE Risk

Point estimates suggest there is no increased risk of MACE with liraglutide, exenatide twice daily, albiglutide, and dulaglutide relative to controls although their associated 95% CIs were wide (Fig. 3) [50, 51, 53]. While the RRs for adjudicated MACE were less than 1.0 compared with comparators, the upper 95% CI boundaries were greater than 1.3 except for dulaglutide. Importantly, the RRs and 95% CIs of MACE associated with liraglutide and exenatide were consistent across multiple analysis methods whether it was use of expanded MACE terms or alternative statistical techniques [50, 51]. The upper boundaries of the 95% CIs for MACE HRs associated with albiglutide exceeded 1.3 regardless of whether the control arm was all comparators, placebo, or active comparators [53].

Fig. 3.

Risk of a CV event with GLP-1 receptor agonist according to integrated analyses of patient- and trial-level data. AEs adverse events, CI confidence interval, CV cardiovascular, GLP-1 glucagon-like peptide-1, HR hazard ratio, MACE major adverse cardiac events, OR odds ratio, RR risk ratio. aPrimary endpoint: MACE composite endpoint or hospital admission for unstable angina [53]. bSecondary endpoint: MACE composite endpoint only [53]. cSecondary MACE composite endpoint, which included all relevant CV AEs [i.e., all terms of the primary MACE endpoint plus terms for arrhythmia, heart failure (with or without hospitalization), and mechanical-related events] [51]

Aside from a protective effect of dulaglutide regarding nonfatal MI, there was no effect of albiglutide and dulaglutide on the risk for MACE components in the two pooled analyses that reported such data (Table 4) [53, 54].

Meta-analyses

Features

We identified four meta-analyses of GLP-1 receptor agonists for assessment (Table 2) [12, 41, 55, 56]. One meta-analysis of trial-level data reported comparisons between GLP-1 receptor agonists and non-GLP-1 receptor agonists [12]. Composite data were taken from 37 trials of which 33, 29, 29, 33, and 31 reported on MACE, MI, stroke, all-cause mortality, and CV mortality, respectively, and 25 reported at least one event [12]. Most of the 37 trials pertained to exenatide (n = 21 for exenatide twice daily; n = 5 for exenatide once daily), with eight trials of liraglutide, two of albiglutide, and one of taspoglutide. These studies enrolled a total of 15,398 patients at low risk for a MACE, including 8619 assigned to treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist and 6779 assigned to a comparator (Table 3) [12]. The definition of MACE was the same as that reported by Monami et al. in a large meta-analysis of DPP-4 inhibitor therapy [12, 29].

MACE Risk

Similar to the findings of the pooled analyses of liraglutide and exenatide twice daily, the meta-analysis by Monami et al. suggested no increased risk for MACE with GLP-1 receptor agonists as a drug class relative to all comparators (OR 0.78; 95% CI 0.54–1.13; P = 0.18) (Fig. 3) [12]. Subgroup analysis found that GLP-1 receptor agonists could be associated with a significant reduction in the incidence of MACE relative to placebo (OR 0.51; 95% CI 0.28–0.93; P = 0.029) and pioglitazone (OR 0.12; 95% CI 0.02–0.99; P = 0.049), but no such benefit was observed relative to DPP-4 inhibitors, sulfonylureas, or insulin. No significant effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists was observed on any component of the MACE endpoint (Table 4).

A second meta-analysis was a pairwise analysis of 15,883 patients who participated in 45 randomized controlled trials [55]. It was designed to reveal any significant differences between GLP-1 receptor agonists and placebo, active comparators, or another GLP-1 agent on CV safety (i.e., CV mortality, ischemic heart disease, nonfatal HF, and stroke). The incidence of CV events with GLP-1 receptor agonists and placebo was low [40/5826 (0.7%) and 28/2350 (1.2%), respectively], and no significant association could be detected (OR 0.7; 95% CI 0.40–1.22; P = 0.2). Similarly, the incidences of CV events for GLP-1 receptor agonists and active comparators were low (0.9% and 0.7%, respectively), yielding an OR of 1.06 (95% CI 0.65–1.74; P = 0.8). A network analysis, which was conducted on the same dataset to support the pairwise analysis and to supplement missing evidence of direct comparisons of GLP-1 receptor agonists, found no statistically significant difference in CV events between any comparisons. Subgroup analysis of the pairwise comparisons did not detect any difference in CV events with respect to study duration (less than 52 weeks versus 52 weeks or longer) or individual GLP-1 receptor agonists versus comparator [55].

Table 4 shows that the GLP-1 receptor agonist drug class and its members were not associated with increasing risk of MACE components, including heart failure, on the basis of results of three meta-analyses [12, 41, 56], although there was evidence associating exenatide with increased risk of arrhythmia (OR 2.83; 95% CI 1.06–7.57) [41].

Randomized Controlled Trial Data

We identified one primary article each for the Evaluation of Lixisenatide in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ELIXA) trial [48] and the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results (LEADER) trial [57].

ELIXA was the first randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial to assess the effects of a GLP-1 receptor agonist (lixisenatide) versus placebo on CV outcomes in patients with T2DM (baseline mean HbA1c level, 7.6%) receiving locally determined standards of care [48]. Participants of ELIXA had had an acute coronary event (i.e., within 180 days before screening), although not as recently as those who took part in EXAMINE [28, 48]. A starting lixisenatide dosage of 10 μg/day was administered during the first 2 weeks and then increased to a maximum dosage of 20 μg/day at the investigator’s discretion [48]. Over a median follow-up period of 25 months, lixisenatide was noninferior to placebo regarding time to first MACE (composite of CV death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina) as the upper boundary of the 95% CI of the HR was less than 1.3 (HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.89–1.17; P < 0.001; Table 5). Superiority of lixisenatide to placebo was also not demonstrated since the upper boundary of the 95% CI was not less than 1.0 (P = 0.81). There was no statistical separation between the groups with respect to rate of hospitalization for HF (HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.75–1.23; P = 0.75 for superiority) [48].

LEADER was a randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial of 9340 T2DM patients who had a higher baseline HbA1c level than the other CV outcome trials (mean, 8.7%) [57]. Patients were stratified by baseline eGFR status (<30 or ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 of body surface area) and assigned with equal probability to treatment with either 1.8 mg (or the maximum tolerated dose) of liraglutide (n = 4668) or placebo (n = 4672) once daily as a subcutaneous injection in addition to standard care. Use of antihyperglycemic therapy was permitted for the attainment of an HbA1c less than 7.0%. Eligible patients were either (1) 50 years of age or more with at least one coexisting CV condition (coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease of stage ≥3, or chronic HF of New York Heart Association class II or III); or (2) 60 years of age or more with at least one CV risk factor (microalbuminuria or proteinuria, hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy, left ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction, or an ankle–brachial index [the ratio of the systolic blood pressure at the ankle to the systolic blood pressure in the arm] of less than 0.9). In LEADER, the primary composite outcome in the survival analysis was the first occurrence of death from CV causes, nonfatal (including silent) MI, or nonfatal stroke. During a median follow-up of 3.8 years, the primary MACE outcome occurred in a lower proportion of patients in the liraglutide group than in the placebo group (13.0% versus 14.9%; HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.78–0.97; P < 0.001 for noninferiority; P = 0.01 for superiority; Table 5). There was no difference between the groups regarding risk of hospitalization for HF (HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.73–1.05; P = 0.14 for superiority).

Conclusions

CV risk is around twice as great in patients with than without T2DM [58], with degree of risk correlating with HbA1c level [59]. Consequently, achievement of tight glycemic control whilst minimizing CV risk is an important treatment objective in the management of T2DM [2]. This aim is supported by 10-year follow-up data from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), which highlight the importance of intensive glycemic control not only for reduction of microvascular endpoints but also for emergent risk reduction for MI and death from any cause [3]. Yet, other data have shown limited benefits of intensive glycemic control on all-cause mortality and CV deaths, with hypoglycemia-associated harm outweighing potential benefits [5, 20]. This discrepancy might be explained by diabetes duration; the findings of recent large-scale trials such as Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD), Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE), and the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial are derived from patient populations with T2DM of moderate-to-long duration [4]. While trials with less favorable CV outcomes have tended to be those in which the risk of severe hypoglycemia associated with treatment intensification is greater [60], post hoc analysis of ACCORD data indicate that it may be factors relating to a persistent average HbA1c greater than 7% that are associated with excessive all-cause mortality rather than intensive glycemic control regimens per se [61].

Our systematic literature review presents findings supporting the premise that short-term treatment of T2DM with DPP-4 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists is not associated with an increased risk of MACE, and on the contrary, that liraglutide reduces MACE risk by 13% versus placebo in patients at high risk for MACE. Indeed, an interesting finding from the ELIXA and LEADER trials was the potential for an inter-drug class difference on MACE risk with respect to GLP-1 receptor agonists: time to death from a MACE was lower with liraglutide than with placebo in LEADER, which was not the case with lixisenatide versus placebo in ELIXA [48, 57]. Furthermore, since our June 21, 2016 search, the Trial to Evaluate Cardiovascular and Other Long-term Outcomes with Semaglutide in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes (SUSTAIN-6) has been published [62]. The main finding of SUSTAIN-6, which included 3297 patients at high CV risk, was that semaglutide was noninferior to placebo regarding rate of first occurrence of MACE (HR 0.74; 95% CI 0.58–0.95; P < 0.001 for noninferiority) [62].