Abstract

We herein report an unusual case of an infected descending aortic pseudoaneurysm with luminal pathognomonic oscillating vegetation with serological findings and clinical features mimicking anti-proteinase 3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. The positive blood cultures and imaging findings, including a pseudoaneurysm and vegetations in the aorta, suggested the presence of an infected aortic aneurysm. The patient was successfully treated with antibiotics and endovascular aortic repair. A precise diagnosis is crucial in order to avoid inappropriate therapy such as immunosuppressive treatment, which could result in life-threatening consequences in a patient with an infected aortic aneurysm.

Keywords: aortic pseudoaneurysm, endovascular aortic repair, PR3-ANCA, vasculitis, vegetation

Introduction

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) correlate well with a wide spectrum of vasculitis manifestations, including Wegener's granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome, all of which are commonly referred to as ANCA-associated vasculitis (1). Several infections, particularly infective endocarditis, have been reported to show positive findings on ANCA tests; furthermore, their clinical features have been acknowledged to mimic ANCA-associated vasculitis, which may lead to a misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment (2,3). However, to our knowledge, infected aortic aneurysms have not been reported to show positive findings on ANCA tests. We herein report a patient with an infected thoracic aortic aneurysm mimicking anti-proteinase 3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA)-associated vasculitis. Vegetations in the descending aorta, which were detected using transesophageal echocardiography, contributed to the diagnosis in this case.

Case Report

A woman in her 60s was admitted to the Nagoya City University Hospital complaining of a fever, which had persisted for three weeks, along with a loss of appetite, proteinuria, hematuria, and renal dysfunction. Her renal function test values had been in the normal range three months prior to the admission. She had bilateral carotid artery stenosis, which was treated with aspirin. She also had a history of orbital mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, which was in remission after treatment with only radiation therapy.

A physical examination at the time of admission revealed a body temperature of 38.1℃, pulse rate 109 beats/min, and blood pressure 104/53 mmHg. Bilateral carotid bruit was heard. The laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell count of 18,900/mm3, hemoglobin 6.6 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen 30.8 mg/dL, serum creatinine 2.24 mg/dL, and C-reactive protein (CRP) 9.44 mg/dL (Table). The antinuclear antibody and rheumatic factor findings were negative. The PR3-ANCA titer was 47.4 IU/mL (normal range <10 IU/mL), although her myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (MPO-ANCA) titer was not elevated. A urinalysis gave results of 2+ for protein and 3+ for occult blood in a dipstick examination, and a microscopic examination detected more than 100 red blood cells per high-power field.

Table.

Laboratory Data at the Time of Admission.

| Hematology | Serology | |||

| White blood cells | 18,900 /mm3 | CRP | 9.44 mg/dL | |

| Red blood cells | 2.47×106 /mm3 | ANA | 1:40 | |

| Hemoglobin | 6.6 g/dL | C3 | 116 mg/dL | |

| Platelets | 335,000 /mm3 | C4 | 33 mg/dL | |

| CH50 | 75.0 IU/mL | |||

| Biochemistry | RF | (-) | ||

| Total protein | 7.2 g/dL | Anti-ds-DNA antibody | 10 IU/mL | |

| Albumin | 2.7 g/dL | MPO-ANCA | 1.2 IU/mL | |

| ALT | 15 IU/L | PR3-ANCA | 47.4 IU/mL | |

| AST | 20 IU/L | |||

| LDH | 201 IU/L | Urinalysis | ||

| Blood urea nitrogen | 30.8 mg/dL | Occult blood | (3+) | |

| Creatinine | 2.24 mg/dL | Protein | (2+) | |

| Na | 135 mEq/L | Glucose | (-) | |

| K | 3.9 mEq/L | Leukocyte | 10-19/HPF | |

| Cl | 99 mEq/L | Red blood cell cast | >100/HPF | |

| Glucose | 134 mg/dL |

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase, ANA: Antinuclear antibodies, AST: Aspartate transaminase, C3: Compliment 3, C4: Compliment 4, CH50: 50% hemolytic unit of complement, CRP: C-reactive protein, DNA: Deoxyribonucleic acid, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, MPO-ANCA: myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, RF: Rheumatic factor, PR3-ANCA: anti-proteinase 3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

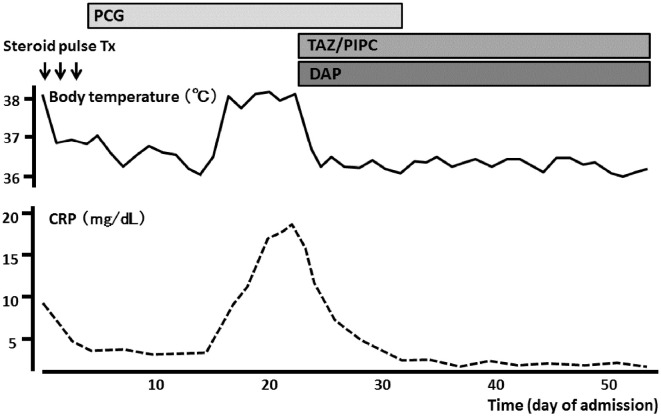

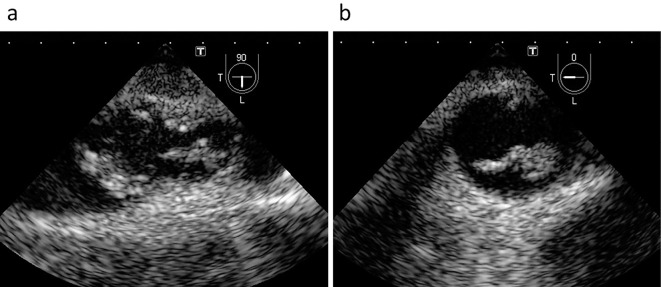

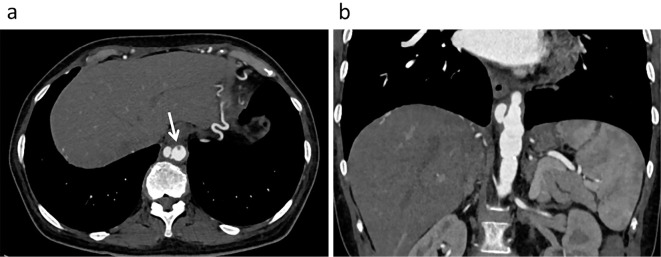

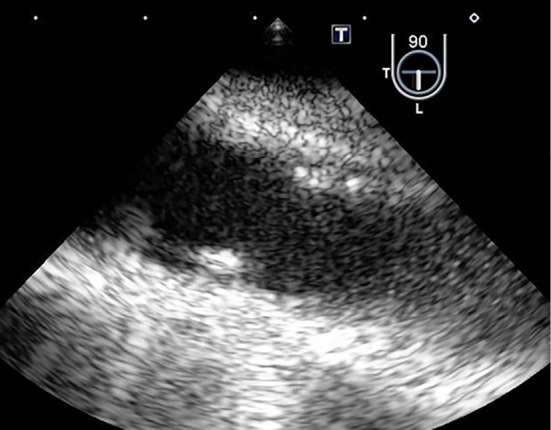

She was initially diagnosed with PR3-ANCA-associated vasculitis and was thereafter treated with methylprednisolone pulse therapy (500 mg/day) for three days (Fig. 1). However, Streptococcus sanguis was serially detected in blood cultures; therefore, the administration of steroids was stopped. She was then transferred to the Cardiology Department. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed no valvular abnormalities and no vegetation in the heart. Transesophageal echocardiography also revealed no vegetation in the heart; however, it showed many oscillating masses attached to the intima in the descending aorta (Fig. 2). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed a new descending aortic aneurysm (Fig. 3). We strongly suspected a pseudoaneurysm based on the shape of the aneurysm. She was ultimately diagnosed with an infected thoracic aortic aneurysm.

Figure 1.

Effects of antibiotics on fever and C-reactive protein during hospitalization. The patient finally became afebrile and has C-reactive protein levels within the normal range after receiving antibiotics. CRP: C-reactive protein, DAP: daptomycin, PCG: penicillin G, TAZ/PIPC: tazobactam/piperacillin, Tx: therapy

Figure 2.

Transesophageal echocardiographic images of the descending aorta, with sectioning planes at 90° (a) and 0° (b). Many oscillating masses attached to the intima were seen in the lumen of the descending aorta.

Figure 3.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic images in the axial (a) and frontal (b) sections. These images show a descending aortic pseudoaneurysm and a contrast defect (arrow) beside the aneurysm that is compatible with echo-documented vegetation.

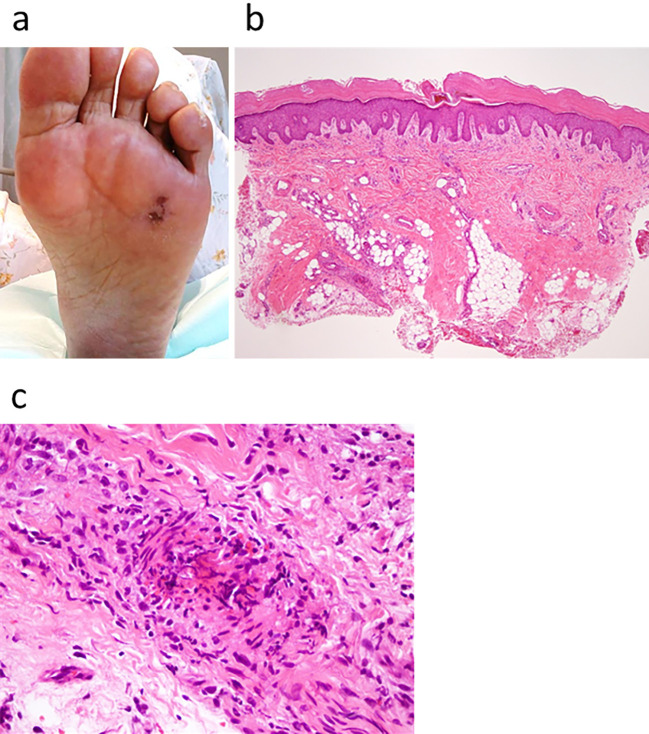

Based on the results of microbiological testing, antibiotic treatment with intravenous penicillin G (24,000,000 unit/day) was started, after which she became afebrile. We added intravenous daptomycin (300 mg every 24 hours) and tazobactam/piperacillin (2.25 g every 6 hours) to the penicillin G because recurrent fever was observed two weeks later. This additional antibiotic treatment made her afebrile again, and her renal function was recovered (Fig. 1). During the antibiotic treatment, she developed a Janeway lesion, which was confirmed by the pathological finding of a skin biopsy specimen (Fig. 4). Transesophageal echocardiography finally demonstrated that the vegetation had disappeared after the antibiotic treatment (Fig. 5), but contrast-enhanced CT revealed that the aneurysm remained unchanged in form.

Figure 4.

A nontender hemorrhagic macular on the sole of the foot (a). Photomicrograph of the macular lesion shows microembolization with fibrin and infiltration of neutrophilic cells Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (b,c). These findings are compatible with a Janeway lesion.

Figure 5.

A transesophageal echocardiographic image of the descending aorta after the antibiotic treatment, with the sectioning plane at 90°. Many oscillating masses have disappeared.

On the 54th hospital day, she underwent endovascular aortic repair (EVAR) of the aneurysm (Fig. 6) after confirmation that her CRP level was in the normal range and once blood cultures were consistently negative. She recovered from the stenting procedure uneventfully. One year after the procedure, she continues to take oral antibiotics; no complications related to stent-graft deployment or recurrent infections have been encountered. Her PR3-ANCA titer has normalized.

Figure 6.

A contrast-enhanced computed tomographic image after endovascular stent graft repair. It shows a successfully occluded infected pseudoaneurysm.

Discussion

In this case, an infected aortic aneurysm exhibited elevated the patient's PR3-ANCA level, and its clinical course mimicked PR3-ANCA-associated vasculitis. This case also manifested characteristic vegetation in the descending aortic lumen.

The detection of ANCAs is highly specific for a diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis (4); however, a number of infections can result in a positive ANCA test. There are several reports of infective endocarditis with the presence of ANCAs that mimic the clinical manifestations of an ANCA-associated vasculitis such as glomerulonephritis (2,3). In the present case, based on the finding of positive blood cultures, we suspected that the patient was experiencing not ANCA-associated vasculitis but infective endocarditis. However, no vegetations were detected in the cardiac chambers using transthoracic echocardiography or transesophageal echocardiography. Instead, contrast-enhanced CT revealed a pseudoaneurysm in the descending aorta, which suggested that the patient had an infected aneurysm. Her renal dysfunction and elevated PR3-ANCA levels normalized with clinical resolution of the infected aneurysm after the administration of appropriate antibiotic therapy and EVAR. The patient has remained free of any evidence of systemic vasculitis during follow-up. The presence of PR3-ANCA may have been falsely positive in the present patient. To our knowledge, this is the first report of an infected aortic aneurysm with a positive PR3-ANCA test and clinical features mimicking ANCA-associated vasculitis.

We found vegetations in the infected aortic aneurysm. The presence of vegetations in the heart is one of the most characteristic findings of infective endocarditis. These vegetations are composed of bacteria, platelets, and inflammatory cells interspersed with fibrin mesh, either on damaged endocardium, including native cardiac valves, or prosthetic valves (5). In the present case, many oscillating masses were detected in the descending aorta on transesophageal echocardiography. Because these masses disappeared after antibiotic treatment, they were considered to be vegetations. A pathological examination of the macular hemorrhages on the patient's sole indicated not a cholesterol embolization but rather a Janeway lesion, which was the consequence of septic embolic events. We therefore suspected that these masses were not mobile plaques but bacterial vegetations. To our knowledge, few cases of infected native aortic aneurysm manifesting vegetations in the aneurysm have been reported (6-8).

The implication of the presence of ANCAs in an infected aortic aneurysm remains unclear. Several mechanisms have been proposed regarding how ANCAs are formed during the course of infection, such as autoantigen complementarity, molecular mimicry, epigenetics, neutrophil extracellular traps, and microbial-sensing proteins called Toll-like receptors (9). There may be a great degree of overlap in the clinical and laboratory manifestations between ANCA-associated vasculitis and ANCA-positive infected aortic aneurysm, potentially leading to a misdiagnosis. It is important to correctly diagnose these cases in order to avoid administering inappropriate therapy, such as immunosuppressive treatment, which might have life-threatening consequences in a patient with an infected aortic aneurysm. Positive blood cultures and imaging findings, such as a pseudoaneurysm and/or vegetations in the aorta, suggest the presence of an infected aortic aneurysm.

A combination of conventional surgical treatment with resection of the aneurysm, extensive local debridement, and revascularization by in situ reconstruction or extra-anatomic bypass may be the gold standard, but such a treatment strategy is accompanied by a high mortality and morbidity. In the present case, the anatomic location of the aneurysm made surgical repair very demanding. It was recently reported that EVAR of an infected aortic aneurysm is feasible and, for most patients, a durable treatment option (10). We therefore treated the present patient successfully with EVAR.

Given that the continuous administration of antibiotics for the infected aneurysm should prevent a recurrence of local infection, we continued using antibiotics until the infection was controlled and carefully monitored the shape of the pseudoaneurysm on contrast-enhanced CT. We were ready to perform an emergency surgical correction at any point during this patient's treatment course.

In conclusion, we herein reported an unusual case of infected descending aortic pseudoaneurysm with luminal pathognomonic oscillating vegetation and with serological findings and clinical features mimicking PR3-ANCA-associated vasculitis.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Gross WL, Csernok E. Immunodiagnostic and pathophysiologic aspects of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 7: 11-19, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Konstantinov KN, Emil SN, Barry M, Kellie S, Tzamaloukas AH. Glomerular disease in patients with infectious processes developing antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. ISRN Nephrol 2013: 324315, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ying CM, Yao DT, Ding HH, Yang CD. Infective endocarditis with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody: report of 13 cases and literature review. PLoS One 9: e89777, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hagen EC, Daha MR, Hermans J, et al. Diagnostic value of standardized assays for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in idiopathic systemic vasculitis. EC/BCR Project for ANCA Assay Standardization. Kidney Int 53: 743-753, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vanassche T, Peetermans WE, Herregods MC, Herijgers P, Verhamme P. Anti-thrombotic therapy in infective endocarditis. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 9: 1203-1219, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Looi JL, Cheung L, Lee AP. Salmonella mycotic aneurysm: a rare cause of fever and back pain in elderly. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 29: 529-531, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lopes R, Almeida J, Dias P, Pinho P, Maciel MJ. Early diagnosis of nonaneurysmal infectious thoracic aortitis using transesophageal echocardiogram in a patient with purulent meningitis. Cardiol Res Pract 2009: 769694, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wein M, Bartel T, Kabatnik M, Sadony V, Dirsch O, Erbel R. Rapid progression of bacterial aortitis to an ascending aortic mycotic aneurysm documented by transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 14: 646-649, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Konstantinov KN, Ulff-Møller CJ, Tzamaloukas AH. Infections and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies: triggering mechanisms. Autoimmun Rev 14: 201-203, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sörelius K, Mani K, Björck M, et al. Endovascular treatment of mycotic aortic aneurysms: a European multicenter study. Circulation 130: 2136-2142, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]