Abstract

We herein report two cases of proteinase 3-anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA)-related nephritis in infectious endocarditis. In both cases, the patients were middle-aged men with proteinuria and hematuria, hypoalbuminemia, decreased kidney function, anemia, elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, and PR3-ANCA positivity. Each had bacteremia, due to Enterococcus faecium in one and Streptococcus bovis in the other. One patient received aortic valve replacement therapy for aortic regurgitation with vegetation, and the other underwent tricuspid valve replacement therapy and closure of a ventricular septic defect to treat tricuspid regurgitation with vegetation. These patients' urinary abnormalities and PR3-ANCA titers improved at 6 months after surgery following antibiotic treatment without steroid therapy.

Keywords: infectious endocarditis, surgical operation, antibiotics, PR3-ANCA-related nephritis

Introduction

Glomerulonephritis in infectious endocarditis was first characterized in 1912 as a focal segmental glomerulosclerosis caused by bacterial emboli (1). In the 1970s, cases of infectious endocarditis-related nephritis were found to exhibit immune complex formation, specifically C3-deposition glomerulonephritis associated with hypocomplementemia (2). A review by Neugarten and Baldwin in 1984 reported that the incidence of glomerulonephritis in infectious endocarditis exceeded 75% in the pre-antibiotic era, but decreased to 8-14% after antibiotics came into use. Necropsy specimens from patients with infectious endocarditis have revealed that almost 25% had focal segmental glomerulonephritis (3). However, in the 1980s, the presence of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) was reported in patients with crescentic glomerulonephritis, especially those with pauci-immune glomerulonephritis or microscopic angiitis. Subsequently, several studies in the early 1990s demonstrated a relationship between infectious endocarditis and proteinase 3-ANCA (PR3-ANCA) (4-9). We herein report two cases of infectious endocarditis associated with glomerulonephritis (proteinuria and hematuria) accompanied by the presence of PR3-ANCA and discuss therapeutic approaches based on a literature review.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 41-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for persistent mild fever and purpura of the lower extremities. Eight months prior to admission, he was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis and treated with mesalazine (5-aminosaliciylic acid) at a local hospital. Two months prior to admission, he received dental treatment and subsequently developed a persistent mild fever and lower extremity edema and purpura. One week prior to admission, he visited a local clinic and was found to have a heart murmur as well as anemia and urinary abnormalities. An ultrasound study of the heart revealed aortic valve insufficiency, and the patient was referred to our hospital. On admission, his mental status was normal, height was 171 cm, and weight was 57.5 kg. His body temperature was 38.0℃, pulse rate was 90 beats/min and regular, respiratory rate was 20 breaths/min, and blood pressure was 130/59 mmHg. Physical examination revealed a systolic murmur (Levine classification 3/6) in the aortic area, as well as pitting edema and purpura of the lower extremities. Laboratory studies indicated 3+ proteinuria (1.5 g/day), 3+ urine occult blood with 100 red blood cells per high power field (RBC/HPF), a white blood cell count of 6100, a red blood cell count of 292×104/μL, hemoglobin of 7.7 g/dL, hematocrit of 23.1%, a platelet count of 13.0×104/μL, albumin level of 2.4 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen level of 24.6 mg/dL, serum creatinine level of 1.33 mg/dL, and total cholesterol level of 121 mg/dL. His Na level was 140 mEq/L, K level was 3.8 mEq/L, Cl level was 110 mEq/L, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 4.46 mg/dL. The findings for rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-hepatitis B antibody, and hepatitis C virus antibody were negative. The level of myeloperoxidase (MPO)-ANCA was normal, while that of PR3-ANCA was 57 EU/mL (normal range: below 10). His C3, C4, and CH50 levels were 40 mg/dL (normal range: 60-120), 16 mg/dL (normal range: 18-40), and 9.9 U/mL (normal range: 30-40), respectively. His IgG, IgA, and IgM antibody levels were 2,104 mg/dL, 574 mg/dL, and 159 mg/dL, respectively. A blood culture examination revealed the presence of Enterococcus faecium, and an ultrasound cardiac examination demonstrated aortic regurgitation with vegetation.

Clinical course

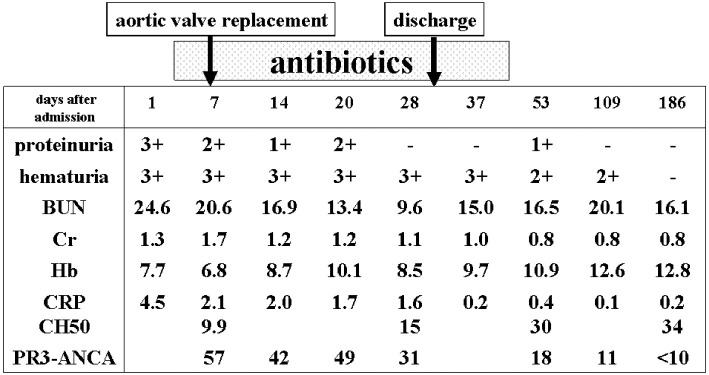

On the seventh hospital day, he underwent aortic valve replacement and was subsequently treated with antibiotics (piperacillin and sulbactam/ampicillin) for one month followed by levofloxacin for a further two weeks. Five months after being discharge, his proteinuria and hematuria had resolved, and his levels of creatinine, hemoglobin, CRP, and PR3-ANCA had returned to normal ranges (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The clinical course of Case 1.

Case 2

A 39-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for 10 days of general fatigue and pitting edema of the legs. At the onset of symptoms he had visited a local clinic, which detected nephrotic syndrome and decreased kidney function, and he was referred to a local general hospital. A blood culture on admission demonstrated Gram-positive bacteremia, and he was subsequently referred to our hospital. He was noted to have been diagnosed with a ventricular septal defect (VSD) during childhood.

On admission to our hospital, his mental status was normal, height was 165 cm, and weight was 59.8 kg. His body temperature was 36.7℃, pulse rate was 83 beats/min and regular, respiratory rate was 12 breaths/min, and blood pressure was 139/80 mmHg. Physical examination revealed a holosystolic murmur (Levine classification 4/6) at the left sternal border, as well as pitting edema of the legs. No Osler nodes or Janeway's lesions were observed. He had not received dental treatment before the present episode. Laboratory studies indicated 1+ proteinuria (0.5 g/g creatinine), 3+ urine occult blood with 100 RBC/HPF, a white blood cell count of 4500, a red blood cell count of 306×104/μL, hemoglobin of 8.4 g/dL, hematocrit of 23.1%, a platelet count of 11.5×104/μL, albumin level of 2.2 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen level of 15.2 mg/dL, serum creatinine level of 1.17 mg/dL, and total cholesterol level of 90 mg/dL. His Na level was 139 mEq/L, K level was 3.5 mEq/L, Cl level was 104 mEq/L, and CRP level was 4.06 mg/dL. The findings for rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-hepatitis B antibody, and hepatitis C virus antibody were negative. The level of MPO-ANCA was normal, while that of PR3-ANCA was 18.5 EU/mL (normal range: below 3.5). His C3, C4, and CH50 levels were 68 mg/dL (normal range: 60-120), 23 mg/dL (normal range: 18-40), and 45.1 U/mL (normal range: 30-40), respectively. His IgG, IgA, and IgM antibody levels were 2,104 mg/dL, 574 mg/dL, and 159 mg/dL, respectively. A blood culture examination revealed the presence of Streptococcus bovis.

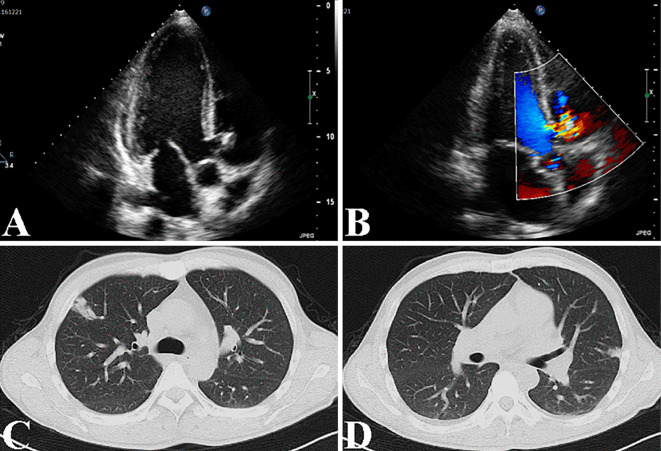

A chest X-ray showed cardiac enlargement, with a cardiothoracic ratio of 51.5%. An ultrasound cardiac examination demonstrated a VSD and tricuspid regurgitation with a 10-mm vegetation and an ejection fraction of 73.6% (Fig. 2A and B). Chest and abdominal computed tomography scans revealed multiple patty shadows in both lung fields, suggesting bacterial emboli (Fig. 2C and D), with mild pleural effusion and hepatosplenomegaly.

Figure 2.

The findings for echocardiogram and chest CT in Case 2. Echocardiogram revealed the presence of a VSD and tricuspid regurgitation with a 10-mm sized vegetation and an ejection fraction of 73.6% (A, B). Chest CT revealed multiple patty shadows in both lung fields, suggesting bacterial emboli (C, D).

Clinical course

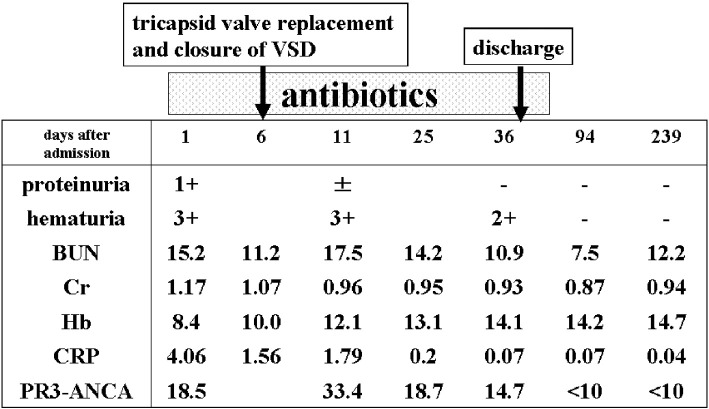

Since blood culture results indicated Gram-positive bacteremia, we intravenously administered 2.0 g/day of meropenem and 350 mg/day of daptomycin. On the second hospital day, we changed the antibiotics dosage to 12 g/day of ampicillin and 120 mg/day of gentamycin to target Streptococcus bovis. On the sixth hospital day, he underwent surgery to replace the tricuspid valve and close the VSD. Postoperatively, the patient took 12 g/day of ampicillin and 350 mg/day of daptomycin for 4 weeks, and then 1.5 g/day of oral amoxicillin for 4 weeks. On the 38th hospital day, the patient was discharged. Two months after being discharged, his urinary abnormalities had resolved and his PR3-ANCA levels had returned to the normal range (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The clinical course of Case 2.

Discussion

The present cases demonstrate three unique points: 1) PR3-ANCA was present in infectious endocarditis; 2) proteinuria, hematuria, and decreased kidney function were compatible with glomerulonephritis; and 3) the PR3-ANCA and urinary abnormalities disappeared after valve replacement surgery and subsequent use of antibiotics without steroids.

The occurrence of glomerulonephritis in a case of infectious endocarditis was first reported in 1912 (1). The main mechanism was initially thought to be immune complex-type glomerulonephritis with hypocomplementemia (3). However, Wagner et al. first showed an association between ANCA and infectious endocarditis in 1991 (4). The combination of PR3-ANCA-related nephritis and infectious endocarditis has been recognized as a clinical disease entity since the case report and literature review of Haseyama et al. in 1998 (7). In 2014, Mahr et al. reported that 20 out of 109 patients with infectious endocarditis (18%) showed the presence of ANCA by indirect immunofluorescence, while enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) demonstrated PR3-ANCA and MPO-ANCA in 4% of cases each. The ANCA-positive subgroup was significantly younger, completely compatible with Duke's criteria, and demonstrated high titers of rheumatoid factor and IgG (8). Ying et al. analyzed 39 patients with infectious endocarditis, and found that in the 13 patients who were positive for PR3-ANCA and in the 26 who were negative, respectively, the occurrence of glomerulonephritis was 30.8% vs. 26.9%, respectively (not significant), with edema of the lower extremities observed in 38.5% vs. 7.7%, respectively (p=0.03) (9). The present two cases also had edema of the lower extremities, and in one patient, purpura was also present. Case 1 may have immune complex type glomerulonephritis, since he exhibited purpura and hypocomplementemia. The presence of hypocomplementemia in Case 1 may therefore depend on the time from onset that the body requires to generate an antibody to bacteria and also produce immune complex, as Case 1 had undergone dental treatment two months prior to admission, whereas Case 2 had experienced symptoms for 10 days before admission (Table).

Table.

Characteristics of Both Cases.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| age, sex | 41 yo, male | 39 yo, male |

| chief complaints | pitting edema, purpura | pitting edema, fatigue |

| time from onset | 2 months after dental treatment | 10 days after general fatigue |

| proteinuria | 3+ (1.5 g/day) | 1+ (0.5 g/g cr) |

| hematuria | 3+ with 100 RBC/HPF | 3+ with 100 RBC/HPF |

| hemoglobin | 7.7 g/dL | 8.4 g/dL |

| albumin | 2.4 g/dL | 2.2 g/dL |

| creatinine | 1.33 mg/dL | 1.17 mg/dL |

| CRP | 4.46 mg/dL | 4.06 mg/dL |

| C3 (60-120) | 40 mg/dL | 68 mg/dL |

| C4 (14-49) | 16 mg/dL | 23 mg/dL |

| CH50 (30-40) | 9.9 U/mL | 45.1 U/mL |

| PR3-ANCA (<10) | 57 EU/mL | 18.5 EU/mL (max: 33.4) |

| bacteremia | Enterococcus faecium | Streptococcus bovis |

| cardiac | aortic regurgitation | VSD with tricuspid regurgitation |

| abnormality | with vegetation | with vegetation |

| surgical operation | aortic valve replacement | tricuspid valve replacement and closure of VSD |

Two potential mechanisms may explain the association between the presence of PR3-ANCA and infectious endocarditis: cardiac valve involvement due to PR3-ANCA-related vasculitis, mainly granulomatous polyangiitis (GPA) (10-13); and infectious endocarditis-induced PR3-ANCA-related vasculitis (14,15). Discriminating between these two conditions can be particularly difficult when patients have no bacteremia or history of valve disease. Final diagnoses in these complex cases should be made by either or both a pathological analysis or bacterial examination of removed valve tissue (12). Physicians should perform trans-esophageal echocardiogram, ANCA level evaluation, and two sets of blood cultures in order to clarify the presence of the above diseases in patients with fever of unknown origin, urinary abnormalities, and cardiac murmur.

In recent years, neutrophil exudate traps (NETs) have been receiving substantial attention with respect to ANCA levels and tissue injury. Neutrophils activated during infection release nuclear-derived chromatin fibers called NETs, which contain histones, PR3, and MPO, all of which are anti-bacterial proteins. NETs themselves directly injure endothelial cells and produce thrombosis. Inflammation is aggravated in tissue exposed to NETs (16). Bacterial PR3 or MPO enhances antibody production against PR3 or MPO (PR3-ANCA, MPO-ANCA). Conversely, PR3-ANCA and MPO-ANCA stimulate neutrophils to secrete NETs. This vicious cycle is proposed as the pathogenetic mechanism underlying ANCA-related vasculitis or glomerulonephritis (17). Previous studies have identified a relationship between ANCA-related diseases and infection (4-9), with PR3-ANCA in infectious endocarditis constituting a typical example.

Infectious endocarditis should be treated using antibiotics for 4 to 6 weeks. However, conventionally, steroids are the first-line therapy for ANCA-related vasculitis or glomerulonephritis. Controversy has been generated regarding appropriate treatment in patients with both ANCA-related disease and infectious endocarditis. While some propose treatment with antibiotics alone (4-6), others propose a combination of antibiotics and steroids (7,18-20), and still others suggest surgery followed by antibiotics without steroids (21,22). When patients with infectious endocarditis and glomerulonephritis show clinical signs of systemic or pulmonary bacterial emboli, we must first consider performing replacement surgery, not a kidney biopsy, in order to prevent exacerbation of their condition. After surgical treatment using an artificial valve, anti-coagulant therapy is needed. In the present two cases, we were unable to perform a kidney biopsy because anti-coagulation drugs were used after valve replacement. However, by 6 months after surgery, the urinary abnormalities and PR3-ANCA levels had improved. Our findings in these two cases suggest that antibiotics and valve replacement without steroids administration are effective when the PR3-ANCA titers and vasculitis activity are not markedly high.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Baehr G. Glomerular lesions of subacute bacterial endocarditis. J Exp Med 15: 330-347, 1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boulton-Jones JM, Sissons JGP, Evans DJ, Peters DK. Renal lesions of subacute infective endocarditis. Br Med J 2: 11-14, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neugarten J, Baldwin DS. Glomerulonephritis in bacterial endocarditis. Am J Med 77: 297-304, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wagner J, Andrassy K, Ritz E. Is vasculitis in subacute bacterial endocarditis associated with ANCA? Lancet 337: 799-800, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Soto A, Jorgensen C, Oksman F, Noel LH, Sany J. Endocarditis associated with ANCA. Clin Exp Rheumatol 12: 203-204, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Subra JF, Michelet C, Laporte J, et al. The presence of cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (C-ANCA) in the course of subacute bacterial endocarditis with glomerular involvement, coincidence or association? Clin Nephrol 49: 15-18, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haseyama T, Imai H, Komatsuda A, et al. Proteinase-3-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (PR3-ANCA) positive crescentic glomerulonephritis in a patient with Down's syndrome and infectious endocarditis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 13: 2142-2146, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mahr A, Batteux F, Tubiana S, et al. ; , IMAGE Study Group. . Brief report: prevalence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in infective endocarditis. Arthritis Rheumatol 66: 1672-1677, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ying CM, Yao DT, Ding HH, Yang CD. Infective endocarditis with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody: report of 13 cases and literature review. PLoS One 9: e89777, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leff RD, Hellman RN, Mullany CJ. Acute aortic insufficiency associated with Wegener granulomatosis. Mayo Clin Proc 74: 897-899, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruisi M, Ruisi P, Finkielstein D. Cardiac manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis: Case report and review of the literature. J Cardiology Cases 2: e99-e102, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Espitia O, Droy L, Pattier S, et al. A case of aortic and mitral valve involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Cardiovasc Pathol 23: 363-365, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McGeoch L, Carette S, Cuthbertson D, et al. ; , Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium. . Cardiac involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Rheumatol 42: 1209-1212, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peng H, Chen WF, Wu C, et al. Culture-negative subacute bacterial endocarditis masquerades as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's granulomatosis) involving both the kidney and lung. BMC Nephrol 13: 174, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Horino T, Takao T, Taniguchi Y, Terada Y. Non-infectious endocarditis in a patient with cANCA-associated small vessel vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 48: 592-594, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schönermarck U, Csernok E, Gross WL. Pathogenesis of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: challenges and solutions 2014. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30 (Suppl 1): i46-i52, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Konstantinov KN, Ulff-Møller CJ, Tzamaloukas AH. Infections and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies: triggering mechanisms. Autoimmun Rev 14: 201-203, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Moing V, Lacassin F, Delahousse M, et al. Use of corticosteroids in glomerulonephritis related to infective endocarditis: three cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 28: 1057-1061, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Konstantinov KN, Harris AA, Hartshorne MF, Tzamaloukas AH. Symptomatic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive disease complicating subacute bacterial endocarditis: to treat or not to treat? Case Rep Nephrol Urol 2: 25-32, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rousseau-Gagnon M, Riopel J, Desjardins A, Garceau D, Agharazii M, Desmeules S. Gemella sanguinis endocarditis with c-ANCA/anti-PR-3-associated immune complex necrotizing glomerulonephritis with a 'full-house' pattern on immunofluorescence microscopy. Clin Kidney J 6: 300-304, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fukasawa H, Hayashi M, Kinoshita N, et al. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis associated with PR3-ANCA positive subacute bacterial endocarditis. Intern Med 51: 2587-2590, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kawamorita Y, Fujigaki Y, Imase A, et al. Successful treatment of infectious endocarditis associated glomerulonephritis mimicking C3 glomerulonephritis in a case with no previous cardiac disease. Case Rep Nephrol 2014: 569047, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]