Abstract

Sporadic inclusion body myositis (sIBM) is a chronic progressive myopathy characterized by muscle weakness of both the quadriceps femoris and finger flexors. We herein present the case of a typical male patient with sIBM, which manifested as the isolated weakness of the finger flexors three years after the disease onset. We have identified several patients with sIBM in our cohort with muscle weakness of the flexors but not the quadriceps femoris. Examination of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle is important for the early and proper diagnosis of sIBM, even if a patient only presents with isolated finger flexor muscle weakness.

Keywords: sporadic inclusion body myositis, finger flexors, flexor digitorum profundus, needle electromyography

Introduction

Sporadic inclusion body myositis (sIBM) is a chronic progressive myopathy characterized by muscle weakness of both the quadriceps femoris (QF) and finger flexors (1-4). The skeletal muscles of sIBM patients show inflammatory cell invasion and a characteristic structure called a rimmed vacuole, suggesting that inflammation and degeneration are both involved in the pathomechanism. The age of disease onset with sIBM tends to be mid-to-later life, where weakness of the quadriceps muscles is the main symptom, often leading to a patient being wheelchair-bound within 5-10 years after the onset of disease. sIBM is generally refractory to current therapy, such as steroids or immunosuppressants.

We previously performed a retrospective survey of Japanese patients with sIBM who had been diagnosed at the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (NCNP). The incidence of sIBM has been suggested to be on the rise (5), making the accurate diagnosis of sIBM all the more crucial.

We herein present the case of a Japanese man with sIBM whose symptoms had begun with progressive weakness of the right finger flexor muscles. He had no symptoms of QF weakness for three years after the disease onset. We also included the results from our 2010 national survey of sIBM in Japan. We advocate the consideration of sIBM as a differential diagnosis among neuromuscular and orthopedic diseases, even when the patient is examined for only isolated weakness of the finger flexor muscles.

Case Report

The present patient began to experience difficulty in bending his right middle and right ring fingertip at 55 years of age. He started to notice that, while playing golf, the golf club often slipped from his fingers. He then began to experience progressive weakness in all of the fingers in his right hand, and it became difficult to write words, fasten a button, and use chopsticks. At 56, he was unable to bend his left fingertips. At 57, he was referred to a neurology clinic. The consulted neurologist (MS) described the patient as having finger flexor weakness without weakness of the QF or other leg or proximal arm muscles. Needle EMG revealed abundant fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves without fasciculation potentials, extremely small motor unit potentials (MUPs) in the flexor digitorium profundus and flexor pollicis longus muscles, and normal recruitment with large MUPs in the biceps brachii muscle. The neurologist suggested a diagnosis of sIBM based on the distribution of weakness and the above EMG findings.

At 58 years of age, the patient felt weakness in his thighs when climbing up the stairs. The weakness in both thighs gradually got worse over time, and he noticed his thighs had become thinner. He monitored the progression of his weakness by the worsening “handicap” score in his golf game. At 59, he experienced difficulty during daily activities involving straddling movement, such as taking a bath. The weakness in both thighs gradually deteriorated, and at 61, he was referred to our hospital for muscle biopsy.

The patient had no family history of muscle disease. He had a medical history of fatty liver and borderline diabetes, dengue fever (hospitalized during a period of travel to the Philippines at 47 years of age), prostate cancer (diagnosed at 59 years of age and treated by surgery; uneventful disease course after treatment), and hypertension (diagnosed at 60 years of age).

On admission, a physical examination showed that he was well nourished (height, 169 cm; weight, 78.8 kg; and body mass index, 27.59 kg/m2). His vital signs were blood pressure 146/96 mmHg, heart rate 63 bpm, and body temperature 35.9℃. A neurological examination revealed hypotonus in the upper limbs, muscle weakness, positivity for Gowers' sign, and slightly unstable hopping on the right side. The manual muscle test (MMT) results were 3/4 (right/left) in the opponens 1st and 2nd fingers, 2/2 in the opponens 1st and 5th fingers, 1/1 in the extensor pollicis longus, 1/2- in the flexor pollicis longus, 0/0 in the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), and 5-/5- in the QF. The findings for other muscles in the lower limbs were normal. The MMT findings are compared between 2011 and 2015 in Table. Remarkably, only one of the finger flexor muscles was affected at least three years after the disease onset. Muscle atrophy was observed in the distal upper limbs, with slight wastage in the proximal frontal lower limbs.

Table.

Manual Muscle Test of the Present Case.

| April 2011 | June 2015 | |

| Trapezius | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Biceps brachii | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Triceps brachii | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Wrist flexor | 5/5 | 5-/5- |

| Wrist extensor | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Flexor pollicis longus (FDL) | 2-/2+ | 1/2- |

| Flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| Abductor pollicis brevis (APB) | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Iliopsoas | 5/5 | 5-/5- |

| Quadriceps femoris (QF) | 5/5 | 4+/4+ |

| Hamstrings | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Tibialis anterior | 5/5 | 5/5 |

| Gastrocnemius | 5/5 | 5/5 |

The scores of right/left side are presented.

Routine biochemical analyses showed increments in aldolase 10.1 IU/L, ALP 418 U/L, γGTP 57 U/L, AST 44 U/L, ALT 64 U/L, LDH 327 U/L, ChE 522 U/L, UA 8.1 mg/dL, CK 720 IU/L, CK-MB 31 U/L, and myoglobin 171 ng/mL. The levels of anti-nuclear antibodies, pyruvate, lactate, and thyroid hormones were all normal. No abnormalities were found in the levels of anti-Jo-1 antibody, HCV, HTLV-1/2, HIV, or acetylcholine receptor antibody.

Electromyogram performed on the right biceps brachii (BB), FDP, and vastus medialis (VM) showed positive sharp waves (in BB and VM) and fibrillation (in VM). Polyphasic motor unit potential (in FDP) and early recruitment (in VM) during slight contraction were also observed. In addition, low amplitude (in FDP and VM) during forceful contraction was also observed.

Whole body CT showed low-density areas reflecting muscle atrophy at the bilateral paraspinal muscles, upper limbs, anterior thighs, and posterior lower legs. Pelvic MRI showed an area of T1-hyperintensity, indicating fatty degeneration in the bilateral QF, particularly in the lateral portion. In addition, fat-suppressed T2WI showed an area of hyperintensity in the same position, indicating muscle inflammation in the medial QF centered on the fascia.

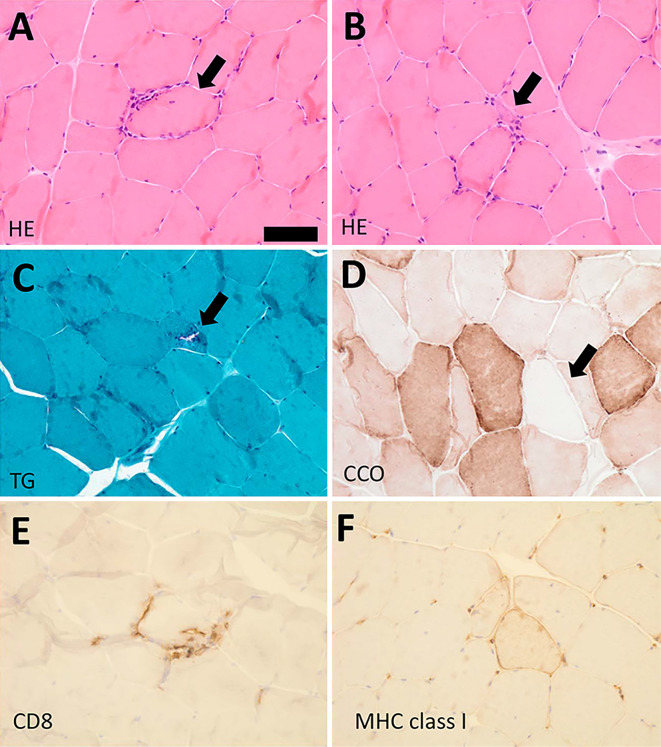

We also performed muscle biopsy from the right VM. Hematoxylin and Eosin staining of the biopsy specimens showed muscle fiber size variation, internal nuclei (4% of all the muscle fibers), and inflammatory cell invasion into the non-necrotic muscle fibers (Figure A). Atrophied muscle fibers were also observed (Figure B). Gomori-Trichrome staining revealed the presence of rimmed vacuoles (Figure C). Cyclooxygenase negative fibers were also found (Figure D), as was the infiltration of CD8- and MHC class I-positive cells (Figure E and F). Given these clinical characteristics and pathological findings, we diagnosed the patient with probable sIBM (6).

Figure.

A: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining. Mononuclear cell infiltration surrounding non-necrotic muscle fiber (arrow). B: H&E staining. Atrophied muscle fiber (arrow). C: Modified Trichrome-Gomori staining (TG). Rimmed vacuole (arrow). D: Cytochrome-C oxidase (CCO) staining. CCO-negative fibers (arrow). E, F: Immunohistochemistry for CD8 (E), and MHC class I (F). Bar, 50 µm.

Discussion

sIBM is one of the most common chronic progressive myopathies in the elderly. The distribution of the affected muscles is characteristic with selectively in QF and finger flexors. The initial symptom of sIBM has typically been reported as muscle weakness of the QF, and cases of sIBM with other muscle weakness sites of origin are relatively rare. The present case began with weakness of the finger flexor muscles and had a three-year duration of disease without any weakness of the quadriceps muscles. Although we didn't perform a hopping test or nEMG of the QF at the first visit, the patient was still able to play golf and felt no symptoms in his lower limbs even three years after the onset.

A 12-year follow-up study of sIBM in the Netherlands (7) reported that approximately 20% of the patients with sIBM had a median disease duration of 20 years and an MRC grade of the quadricep muscles exceeding 2. Patients rarely had finger flexor weakness in this Dutch study.

To further clarify the characteristics of sIBM in Japan, we conducgted a National Multicenter Survey for sIBM in Japan in 2010 (manuscript in submission). We included both the definite and probable cases of sIBM meeting the clinical and biopsy criteria proposed by Mastaglia (2007) (6). A total of 146 sIBM cases from 8 institutes were diagnosed between January 2000 and December 2009 and were included in this survey.

The most common initial symptom was muscle weakness of the proximal lower limbs, particularly the QF (80%). Weakness of the finger flexors (n=8, 6%), muscle weakness of the proximal upper limbs (4%), dysphagia (3%), fatigability (2%), and myalgia (2%) were also noted. Among the patients with weakness of the finger flexors as an initial symptom, 3 (including the present case) showed a 3-year interval between the disease onset and the appearance of weakness in the lower limb muscles (2%). Examining the FDP muscle would reduce the chances of misdiagnosing sIBM as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or another neuromuscular or orthopedic disorders (8).

Trials for sIBM therapeutic regimens are currently ongoing (9,10), including examinations of the utility of treatments such as the inhibition of activin receptors IIA and IIB (ActRII) using bimagrumab (anti-ActR II antibody) (11). In our present case of a patient presenting with isolated finger flexor muscle weakness, sIBM should be considered as a differential diagnosis to ensure prompt and early intervention.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Research on Measures for Intractable Diseases and Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health from the Japanese Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare (H21-nanchi-ippan-024, H22-nanchi-ippan-117, H24-nanchi-ippan-028, H26-nanchitou(nan)-ippan-079). Dr. Suzuki received a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (A) from JSPS (15H05667) and a Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (26670436). The authors are grateful to M Narisawa for their technical support. We thank the members of the research group for Research on Measures for Intractable Diseases and all of the patients and families involved in this study. We also thank Naoko Shimakura, Yoko Kanamori, Michiko Yoshida, and Naoko Arai for their assistance with data acquisition.

References

- 1. Mastaglia FL, Needham M. Inclusion body myositis: a review of clinical and genetic aspects, diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches. J Clin Neurosci 22: 6-13, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Needham M, Mastaglia FL. Sporadic inclusion body myositis: a review of recent clinical advances and current approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Neurophysiol 127: 1764-1773, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lloyd TE, Mammen AL, Amato AA, Weiss MD, Needham M, Greenberg SA. Evaluation and construction of diagnostic criteria for inclusion body myositis. Neurology 83: 426-433, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benveniste O, Stenzel W, Hilton-Jones D, Sandri M, Boyer O, van Engelen BG. Amyloid deposits and inflammatory infiltrates in sporadic inclusion body myositis: the inflammatory egg comes before the degenerative chicken. Acta Neuropathol 129: 611-624, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Suzuki N, Aoki M, Mori-Yoshimura M, Hayashi YK, Nonaka I, Nishino I. Increase in number of sporadic inclusion body myositis (sIBM) in Japan. J Neurol 259: 554-556, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Needham M, Mastaglia FL. Inclusion body myositis: current pathogenetic concepts and diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol 6: 620-631, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cox FM, Titulaer MJ, Sont JK, Wintzen AR, Verschuuren JJ, Badrising UA. A 12-year follow-up in sporadic inclusion body myositis: an end stage with major disabilities. Brain 134: 3167-3175, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hokkoku K, Sonoo M, Higashihara M, Stålberg E, Shimizu T. Electromyographs of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle are useful for the diagnosis of inclusion body myositis. Muscle Nerve 46: 181-186, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Machado P, Miller A, Herbelin L, et al. LB0002 Safety and tolerability of arimoclomol in patients with sporadic inclusion body myositis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIa proof-of-concept trial. Ann Rheum Dis 72: A164, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Recher M, Sahrbacher U, Bremer J, Arndt B, Steiner U, Fontana A. Treatment of inclusion body myositis: is low-dose intravenous immunoglobulin the solution? Rheumatology international 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Amato AA, Sivakumar K, Goyal N, et al. Treatment of sporadic inclusion body myositis with bimagrumab. Neurology 83: 2239-2246, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]